The Department of Health in England and Wales is considering new ways to fund treatment with interferon beta and glatiramer for multiple sclerosis (MS), including a unique “risk sharing” scheme in which the drugs would be funded only if treatment trials in individual patients showed they were effective.

The suggestion seems to undermine the recommendation that these drugs should not be funded by the NHS, which was made last week by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the body that advises on the clinical and cost effectiveness of drugs.

A statement released last week set out the unusual proposal: “The Department of Health can confirm that it is in discussions with four manufacturers of beta interferon and related products, as well as other stakeholders. Our discussions are looking at a range of options, including the possibility of a ‘risk-sharing’ scheme in which the drug would be funded for relapsing-remitting MS patients.

“After a period of time an assessment would be made of whether the drug was working for patients. If it were, payments would continue. If not, payments to manufacturers would be reduced on a sliding scale.”

The department's statement argued that the suggestion was, in fact, in line with the institute's provisional appraisal determination on interferon beta and glatiramer for multiple sclerosis released in August. The statement said that “the Department of Health . . . and manufacturers might usefully consider what actions could be taken, jointly, to enable any of the four medicines appraised in this guidance to be secured for patients in the NHS in England and Wales, in a manner which could be considered cost-effective.”

However, Professor Joe Collier, professor of medicines policy at St George's Hospital Medical School, London, said that the health department's proposal for a new type of funding strategy seemed to undermine the role of NICE in advising the NHS on whether or not available evidence supported the funding of new drugs.

He said: “NICE seems to have got itself into a difficult position, where it is not really believed by the government or by doctors. It was obvious that NICE was initially going to get a rough ride—from patients wanting the drug being reviewed, from doctors wanting clinical freedom, and from the pharmaceutical industry. But it hasn't developed into a robust and trusted advisory body.”

Professor Collier considered that the proposal for individual treatment trials with drugs for multiple sclerosis was seriously flawed. “The government wanted a solution so has gone down a route that is not tenable scientifically or clinically. It is a fudged position that is political rather than patient oriented.”

He argued that it would be impossible to tell if a drug was effective in multiple sclerosis just by giving it to a patient to try because of the variable nature of the condition. Only a properly conducted clinical trial could provide a reliable answer. “The solution to this serious muddle will be for NICE to develop as a source of advice that is wanted, trusted, and acted upon by all parties involved.” However, he warned, “this could take some time.”

Neurologists are also concerned that the Department of Health's proposal for treatment trials in individual patients would be impossible to implement. Dr Mohammed Sharief, consultant neurologist and senior lecturer at Guys', King's, and St Thomas's School of Medicine, London, said: “In my view, this is not a clinically viable proposition. There are, as yet, no internationally approved criteria for treatment success or failure in multiple sclerosis.”

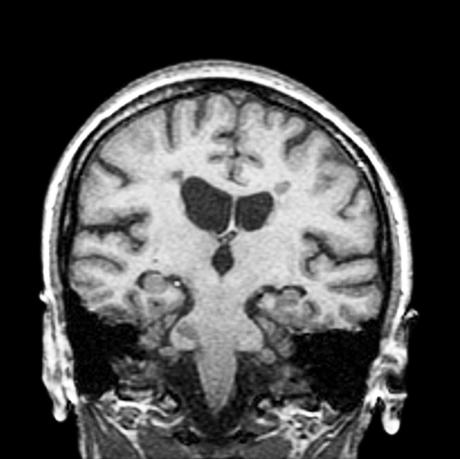

He argued that monitoring of treatment efficacy would be difficult and expensive. Multiple sclerosis is currently assessed on three criteria—gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, which detects active plaques in the nervous system; expanded disability status score; and clinical relapses, defined as sudden changes in neurological status lasting more than 48 hours in the absence of infection. “These sound clear but are actually very difficult to assess,” he noted, adding that monthly magnetic resonance imaging would cost £6000 ($9000) each year for each patient.

Dr Sharief considers that NICE should follow guidelines developed by the Association of British Neurologists, which recommends that interferon beta should be considered in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis who are still mobile and who have experienced three relapses in the previous two years. “The Department of Health's proposal for treatment trials in individual patients is just a short term suggestion to divert patients' anger about the NICE decision.”

The possibility of political motivation behind the department's proposal could be supported by the fact that it was disclosed by the UK media on 31 October, two days before NICE published its “final appraisal determination.” This stated: “On the balance of their clinical and cost effectiveness neither beta interferon nor glatiramer acetate is recommended for the treatment of multiple sclerosis in the NHS in England and Wales” (www.nice.org.uk).

This recommendation has now been sent to all those who were consulted in the appraisal process for them to consider making final appeals. The document reinforced the idea of new strategies for funding the drugs considered, noting: “The Department of Health and the National Assembly for Wales are invited to consider a strategy with a view to acquiring any or all of the medicines appraised for this guidance in a manner which could be considered to be cost effective.”

The Multiple Sclerosis Society said that it would appeal against the institute's decision, despite the Department of Health's proposal to make the drugs available on the NHS to people whose neurologists consider they benefit from them.

Ken Walker, acting chief executive of the society, said: “We must continue to challenge NICE's decision. It has ignored the compelling evidence of people across the world.”

The Department of Health has temporarily pre-empted any ruling by NICE on the drug imatinib mesylate (Glivec) for chronic myeloid leukaemia. It has written to regional health directors saying that they should pay for the drug when it is licensed later this year. The institute's appraisal is not expected until August 2002 (Lancet 2001;358:1478).

Figure.

DR W CRUM/DEMENTIA RESEARCH GROUP/TIM BEDDOW/SPL

Magnetic resonance imaging scan of a vertical section through a brain with multiple sclerosis