Abstract

Objective

To investigate real-world effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and the association with (i) treatment line (second and third TNFi-series) and (ii) reason for withdrawal from the preceding TNFi [lack of efficacy (LOE) vs adverse events (AE)].

Methods

Prospectively collected routine care data from 12 European registries were pooled. Rates for 12-month drug retention and 6-month remission [Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score C-reactive protein inactive disease (ASDAS-ID)] were assessed in second and third TNFi-series and stratified by withdrawal reason.

Results

We included 8254 s and 2939 third TNFi-series; 12-month drug retention rates were similar (71%). Six-month ASDAS-ID rates were higher for the second (23%) than third TNFi (16%). Twelve-month drug retention rates for patients withdrawing from the preceding TNFi due to AE vs LOE were similar for the second (68% and 67%) and third TNFi (both 68%), while for the second TNFi, rates were lower in primary than secondary non-responders (LOE <26 vs ≥26 weeks) (58% vs 71%, P < 0.001). Six-month ASDAS-ID rates for the second TNFi were higher if the withdrawal reason was AE (27%) vs LOE (17%), P < 0.001, while similar for the third TNFi (19% vs 13%, P = 0.20).

Conclusion

A similar proportion of axSpA patients remained on a second and third TNFi after one year, but with low remission rates for the third TNFi. Remission rates on the second TNFi (but not the third) were higher if the withdrawal reason from the preceding TNFi was AE vs LOE.

Keywords: axial spondyloarthritis, switching TNF-inhibitors, effectiveness, lack of efficacy, adverse events

Rheumatology key messages.

71% of axSpA patients remained on both the second and third TNFi after one year.

Rates for ASDAS inactive disease were higher for the second (23%) than third TNFi (16%).

Low remission rates for the third TNFi highlight the need for other modes of action.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are effective in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) [1, 2], but some patients experience adverse events (AE) or lack/loss of efficacy (LOE) and withdraw from treatment [3, 4]. Limited data are available on the optimal sequence of treatments after failure of a first and second TNFi, and in recent years, other drug classes [interleukin (IL)-17 and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors] have further expanded the treatment armamentarium [5, 6]. Observational studies have suggested a potential benefit from switching to a second TNFi after having failed a first [7–11], while data on switching to a third TNFi after having failed two previous are scarce, although such a scenario is not uncommon in clinical practice [9, 12]. It is also unclear which patients benefit the most from switching, and if the response depends on the reason for withdrawal from the preceding treatment. Previous data on a limited number of patients with RA and axSpA have suggested a higher likelihood of response to the second TNFi, if the reason for switching was either AE or loss of efficacy after an initial response [13–15], i.e. secondary nonresponse [16].

Due to the knowledge gap, the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) have recommended any switch in case of treatment failure of the first TNFi, IL-17 or JAK inhibitor, i.e. between drug classes or within the same drug class, while switches after failure of the second drug are not addressed [17].

The European Spondyloarthritis (EuroSpA) Research Collaboration Network (RCN) has been created to strengthen research on real-world data in patients with SpA, based on secondary use of data from European registries [18, 19].

In this study, we aimed to investigate real-world effectiveness in axSpA patients initiating a second or third TNFi in routine care across Europe. In addition, we aimed to investigate whether the treatment outcomes were associated with the reason for withdrawal (AE or LOE) from the preceding TNFi-treatment. In patients withdrawing due to LOE, we further investigated whether the treatment outcomes differed according to the duration of the preceding treatment.

We hypothesized that treatment effectiveness (retention rates and remission rates) would be higher (i) for the second than for the third TNFi, (ii) in patients withdrawing from the preceding TNFi following AE vs LOE and (iii) in patients switching the preceding TNFi due to LOE after a longer (secondary non-response) vs a shorter treatment duration (primary non-response).

Methods

Patients

Anonymized data from 12 registries participating in the EuroSpA Research Collaboration were uploaded through a secured Virtual Private Network server and pooled: SRQ (Sweden), DANBIO (Denmark), SCQM (Switzerland), NOR-DMARD (Norway), ATTRA (Czech Republic), Reuma.pt (Portugal), BIOBADASER (Spain), ROB-FIN (Finland), biorx.si (Slovenia), ICEBIO (Iceland), TURKBIO (Turkey) and RRBR (Romania). This study included secondary use of data prospectively collected between 1999 and 2018 on patients registered with a diagnosis of axSpA according to the treating rheumatologist. Patients were aged ≥18 years at the time of diagnosis and had been followed in a registry since initiation of their first TNFi, providing data from treatment with their second and, if applicable, the third TNFi. Patients having received either IL17 or JAK inhibitors before or in between the TNFi treatments were excluded. Treatment with a TNFi was based on the treatment start date (defined as baseline) and, if relevant, a stop date as recorded in each registry.

Clinical variables

Baseline data included age, sex, human leucocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) status, body mass index (BMI), time since diagnosis, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) [20], Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) [21], smoking status, line of bDMARD treatment and TNFi agent used. At baseline and at 6, 12 and 24 months follow-up, the following disease scores were included: the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score with C-reactive protein (ASDAS) [22] and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) on a 0–100 millimeter (mm) or numeric rating scale (NRS) [23]. Furthermore, fatigue and global scores on visual analogue scales (VAS) were obtained. In registries using NRS, values were converted to mm.

The 6-month visit was defined as a registered visit from 90 to 270 days after baseline, the 12-month visit as a registered visit from 271 to 545 days after baseline and a 24-month visit as a registered visit from 546 to 910 days after baseline.

Retention rates

Time on drug was defined as the number of days individual patients continued treatment. In patients with no stop date, the drug was assumed to have been discontinued if a new biologic (b)DMARD was recorded in the registry and the discontinuation date was defined as the date of next bDMARD start. If the same drug was re-started within 3 months of the recorded treatment stop date, with no other bDMARD recorded in-between, the treatment periods were considered as one period. Retention rates were calculated as the percentage of patients still on TNFi at 6, 12 and 24 months. Observations were censored by (i) the date of data extraction; (ii) date of death; or (iii) end of registry follow-up, whichever came first. Patients who withdrew due to remission, other reasons or who had no registered withdrawal reason were censored at the stop date.

Clinical remission

Clinical remission was defined as the achievement of ASDAS inactive disease (<1.3).

Study endpoints

The primary endpoints were the crude rates for 12-month TNFi retention and 6-month ASDAS inactive disease for the second and third TNFi. Secondary endpoints were the rates for 12-month TNFi retention and ASDAS inactive disease, stratified by reason for withdrawal (AE or LOE) from the preceding TNFi. In patients who withdrew due to LOE, further stratification according to the duration of treatment was done: LOE after <26 weeks on the preceding TNFi was defined as primary non-response, and LOE after 26 weeks or longer on the preceding TNFi was defined secondary non-response [24].

Additional endpoints were overall 6-month and 24-month drug retention rates, rates for ASDAS inactive disease at 12 and 24 months, and rates for achieving BASDAI <40 mm and <20 mm at 6, 12 and 24 months. Rates for drug retention (6, 12 and 24 months) and ASDAS inactive disease, BASDAI <40 mm and <20 mm at 6 months were also assessed in the individual registries.

Reasons for withdrawal

The withdrawal reason was in all registries based on the opinion of the treating clinician and was assessed in prespecified categories (LOE, AE and other reasons). Patients were excluded from the analyses stratified by withdrawal reason in case of (i) other recorded reasons than AE or LOE or (ii) no recorded reason. If both AE and LOE was given as withdrawal reason, LOE was selected over AE.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed according to a predefined statistical analysis plan using R version 4.2. All calculations were based on observed data; no imputation of missing data was performed. Descriptive statistics [median, interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and percentage with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for categorical variables] were applied for patient characteristics and outcomes. Kaplan–Meier estimation was used to investigate TNFi retention rates, including 95% confidence intervals (CI). Crude and LUNDEX adjusted rates for ASDAS inactive disease, BASDAI <40 mm and BASDAI <20 mm were calculated. A LUNDEX rate is defined as the crude rate adjusted by the retention rate and is calculated as the fraction of starters still in the study at a given time point multiplied by the fraction responding at that time point [25]. Analyses were conducted separately for patients initiating their second and third TNFi with no formal comparisons. In analyses stratified by withdrawal reason (AE vs LOE) and duration of treatment before withdrawal due to LOE (primary vs secondary non-response), comparisons were done using log-rank (retention rates) and χ2 tests (the remaining rates), respectively. A significance level of 0.05 was applied.

Ethics

All participating registries obtained the necessary approvals (including written informed patient consent if needed) in accordance with legal, compliance and regulatory requirements from national Data Protection Agencies and/or Research Ethics Boards prior to the data transfer. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 8254 axSpA patients initiating their second TNFi treatment; of these 2939 also contributed with a third TNFi treatment course (Table 1). We identified 1894 and 4213 patients who initiated a second TNFi following an AE or LOE on the first TNFi treatment, respectively, and 575 and 1644 patients who initiated a third TNFi following AE or LOE on the second TNFi treatment, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Of the remaining 2147 patients who stopped the first TNFi, 1979 had other registered reasons for withdrawal (i.e. remission, planning for pregnancy etc.), while 168 had no registered reason; the corresponding numbers for withdrawal of the second TNFi were 689 patients with other reasons and 31 patients with no registered reason for withdrawal.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with axSpA initiating a second or third TNFi treatment

| Second TNFi (n = 8254) |

Third TNFi (n = 2939) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | |

| Age, years | 8254 | 43 (35–52) | 2939 | 44 (36–53) |

| Male, % | 8254 | 55 | 2939 | 52 |

| HLA-B27-positive, % | 3989 | 66 | 1360 | 66 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | 6010 | 4 (2–11) | 2031 | 6 (3–12) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3323 | 26 (23–29) | 1176 | 26 (23–30) |

| Current smoking, % | 7294 | 24 | 2672 | 24 |

| Infliximab (%) | 8254 | 13 | 2939 | 18 |

| Etanercept (%) | 8254 | 33 | 2939 | 23 |

| Adalimumab (%) | 8254 | 31 | 2939 | 28 |

| Certolizumab pegol (%) | 8254 | 6 | 2939 | 11 |

| Golimumab (%) | 8254 | 16 | 2939 | 20 |

| Calendar year of treatment start | ||||

| Prior to 2009 | 1176 | 14 | 276 | 9 |

| 2009–2011 | 1750 | 21 | 561 | 19 |

| 2012–2014 | 2509 | 30 | 1007 | 34 |

| 2015–2017 | 2819 | 34 | 1095 | 37 |

| CRP, mg/L | 6098 | 5 (2–16) | 2124 | 5 (2–15) |

| ASDAS | 3198 | 3.2 (2.5–4.0) | 1255 | 3.3 (2.5–4.0) |

| BASDAI (mm) | 4610 | 56 (38–72) | 1703 | 60 (41–74) |

| BASFI (mm) | 3978 | 44 (24–66) | 1518 | 48 (27–71) |

| BASMI | 1480 | 2 (1–4) | 519 | 3 (1–5) |

| Physician global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 3212 | 30 (15–50) | 1139 | 31 (16–50) |

| Patient global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 5480 | 62 (40–80) | 1993 | 67 (45–80) |

| Pain score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 5377 | 61 (40–78) | 1971 | 65 (44–80) |

| Fatigue score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 4014 | 65 (41–80) | 1557 | 70 (47–83) |

Data are as observed.

Available n: number of available data from patients treated with a second and if applicable also third TNFi; values were converted to mm for registries using numeric rating scale. ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score with CRP; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BMI: body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; HLA-B27: human leucocyte antigen B27; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of axial spondyloarthritis patients stratified by reason for discontinuation of the preceding TNFi

| Second TNFi (n = 8254) |

Third TNFi (n = 2939) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiating second TNFi due to AE on first TNFi (n = 1894) |

Initiating second TNFi due to LOE on first TNFi (n = 4213) |

Initiating third TNFi due to AE on second TNFi (n = 575) |

Initiating third TNFi due to LOE on second TNFi (n = 1644) |

|||||

| Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | Available na | Median (IQR) or percentage | |

| Age, years | 1894 | 44 (36–53) | 4213 | 44 (35–52) | 575 | 44 (37–54) | 1644 | 44 (37–53) |

| Male, % | 1894 | 52 | 4213 | 54 | 575 | 45 | 1644 | 54 |

| HLA-B27-positive, % | 921 | 65 | 2206 | 64 | 271 | 62 | 794 | 65 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | 1356 | 4 (1–11) | 3188 | 4 (1–10) | 389 | 6 (2–13) | 1165 | 6 (2–12) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 711 | 26 (23–29) | 1772 | 26 (23–30) | 203 | 26 (23–29) | 687 | 26 (23–30) |

| Current smoking, % | 1712 | 25 | 3802 | 24 | 534 | 25 | 1502 | 24 |

| Infliximab (%) | 1894 | 8 | 4213 | 15 | 575 | 12 | 1644 | 21 |

| Etanercept (%) | 1894 | 38 | 4213 | 34 | 575 | 25 | 1644 | 23 |

| Adalimumab (%) | 1894 | 32 | 4213 | 28 | 575 | 31 | 1644 | 23 |

| Certolizumab pegol (%) | 1894 | 5 | 4213 | 7 | 575 | 9 | 1644 | 12 |

| Golimumab (%) | 1894 | 16 | 4213 | 16 | 575 | 23 | 1644 | 21 |

| Calendar year of treatment start | ||||||||

| Prior to 2009 | 343 | 18 | 521 | 12 | 61 | 11 | 153 | 9 |

| 2009–2011 | 451 | 24 | 850 | 20 | 121 | 21 | 319 | 19 |

| 2012–2014 | 543 | 29 | 1356 | 32 | 192 | 33 | 579 | 35 |

| 2015–2017 | 557 | 29 | 1486 | 35 | 201 | 35 | 593 | 36 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1412 | 5 (2–13) | 3153 | 5 (2–17) | 426 | 5 (2–14) | 1184 | 5 (2–16) |

| ASDAS | 680 | 3.1 (2.1–3.9) | 1792 | 3.3 (2.7–4) | 233 | 3.3 (2.3–4) | 717 | 3.3 (2.6–4) |

| BASDAI (mm) | 1064 | 52 (30–69) | 2535 | 60 (44–73) | 328 | 59 (39–72) | 995 | 62 (44–75) |

| BASFI (mm) | 891 | 40 (20–62) | 2265 | 49 (30–69) | 283 | 43 (28–66) | 904 | 50 (30–73) |

| BASMI | 346 | 20 (10–40) | 841 | 30 (10–46) | 108 | 20 (10–40) | 308 | 30 (20–50) |

| Physician global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 724 | 26 (10–48) | 1651 | 37 (20–52) | 208 | 30 (15–50) | 650 | 35 (20–55) |

| Patient global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 1244 | 60 (34–78) | 2806 | 69 (50–80) | 382 | 67 (43–80) | 1116 | 70 (50–81) |

| Pain score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 1229 | 57 (33–75) | 2748 | 67 (50–80) | 376 | 63 (40–80) | 1108 | 67 (49–80) |

| Fatigue score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 909 | 62 (38–80) | 2174 | 70 (50–81) | 298 | 69 (43–83) | 896 | 70 (50–84) |

Data are as observed.

Available n: number of available data from patients treated with a second and if applicable also third TNFi; values were converted to mm for registries using numeric rating scale. AE: adverse events; ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score with CRP; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BMI: body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; HLA-B27: human leucocyte antigen B27; LOE: lack of efficacy; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Table 3.

Drug retention, remission and low disease activity rates in axial spondyloarthritis patients initiating a second or third TNFia

| Retention rates |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients initiating second TNFi (8254) | All patients initiating third TNFi (n = 2939) | |||||||

| Retention at 6 months (95% CI) | 81% (80–81%) | 81% (79–82%) | ||||||

| Retention at 12 months (95% CI) | 71% (70–72%) | 71% (69–72%) | ||||||

| Retention at 24 months (95% CI) | 63% (62–64%) | 61% (59–63%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Initiating second TNFi due to AE on first TNFi (n = 1894) | Initiating second TNFi due to LOE on first TNFi (n = 4213) | Initiating third TNFi due to AE on second TNFi (n = 575) | Initiating third TNFi due to LOE on second TNFi (n = 1644) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Retention at 6 months (95% CI) | 77% (75–79%) | 78% (77–79%) | 76% (73–80%) | 79% (77–81%) | ||||

| Retention at 12 months (95% CI) | 68% (66–70%) | 67% (66–69%) | 68% (64–72%) | 68% (66–71%) | ||||

| Retention at 24 months (95% CI) | 60% (58–63%) | 58% (56–59%) | 60% (56–64%) | 57% (55–60%) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Remission and low disease activity rates | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| All patients initiating second TNFi (n = 8254) | All patients initiating third TNFi (n = 2939) | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Crudeb | LUNDEX adjustedc | Crudeb | LUNDEX adjustedc | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| ASDAS-ID at 6 months | 23% | 17% | 16% | 12% | ||||

| ASDAS-ID at 12 months | 24% | 14% | 16% | 9% | ||||

| ASDAS-ID at 24 months | 26% | 11% | 15% | 6% | ||||

| BASDAI <40 mm at 6 months | 59% | 44% | 49% | 36% | ||||

| BASDAI <40 mm at 12 months | 62% | 36% | 51% | 29% | ||||

| BASDAI <40 mm at 24 months | 66% | 27% | 52% | 20% | ||||

| BASDAI <20 mm at 6 months | 32% | 23% | 24% | 18% | ||||

| BASDAI <20 mm at 12 months | 33% | 19% | 24% | 14% | ||||

| BASDAI <20 mm at 24 months | 36% | 14% | 25% | 10% | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Initiating second TNFi due to AE on first TNFi (n = 1894) | Initiating second TNFi due to LOE on first TNFi (n = 4213) | Initiating third TNFi due to AE on second TNFi (n = 575) | Initiating third TNFi due to LOE on second TNFi (n = 1644) | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Crude | LUNDEX | Crude | LUNDEX | Crude | LUNDEX | Crude | LUNDEX | |

|

| ||||||||

| ASDAS-ID at 6 months | 27% | 19% | 17% | 12% | 19% | 13% | 13% | 10% |

| ASDAS-ID at 12 months | 26% | 15% | 18% | 10% | 17% | 10% | 13% | 7% |

| ASDAS-ID at 24 months | 31% | 13% | 20% | 7% | 17% | 7% | 14% | 5% |

| BASDAI<40 mm at 6 months | 64% | 46% | 54% | 39% | 54% | 38% | 46% | 34% |

| BASDAI <40 mm at 12 months | 65% | 37% | 56% | 31% | 49% | 28% | 47% | 27% |

| BASDAI <40 mm at 24 months | 70% | 29% | 60% | 23% | 60% | 24% | 49% | 19% |

| BASDAI <20 mm at 6 months | 37% | 26% | 25% | 18% | 25% | 18% | 21% | 16% |

| BASDAI <20 mm at 12 months | 36% | 21% | 26% | 14% | 22% | 13% | 21% | 12% |

| BASDAI <20 mm at 24 months | 43% | 18% | 29% | 11% | 28% | 11% | 23% | 9% |

Data are as observed unless otherwise stated, median (IQR) or percentage.

Details on numbers of patients are found in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Rheumatology online.

Crude: The fraction with ASDAS-ID, BASDAS <40 mm and <20 mm, respectively, of those still on drug at 6, 12 and 24 months, respectively.

LUNDEX adjusted: crude value adjusted for drug retention.

AE: adverse events; ASDAS-ID: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score inactive disease; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; LOE: lack of efficacy; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor.

Patients who initiated a second and third TNFi had a median (IQR) time since diagnosis of 4 (2–11) and 6 (3–12) years, respectively, the baseline ASDAS was 3.2 (2.5–4.0) and 3.3 (2.5–4.0) and the BASDAI scores 56 mm (38–72) and 60 mm (41–74), respectively. See Table 1 for additional patient characteristics. In the stratified analyses, patients initiating a second TNFi due to LOE had higher baseline patient global, pain and fatigue scores and higher composite index scores (BASDAI and ASDAS), as compared with patients initiating a second TNFi due to AE. The pattern was similar in patients initiating a third TNFi, but with smaller absolute differences (see Table 2). In the individual registries, the median time since diagnosis for patients switching TNFi treatment ranged from 3 to 9 years (second TNFi) and 4–14 years (third TNFi). Median ASDAS ranged from 3.1–3.8 (second TNFi) and 3.1–3.6 (third TNFi) (see Table 4 and Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online).

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics and disease status at follow-up in axial spondyloarthritis patients initiating a second TNFi

| Registry | SRQ | ATTRA | BIOBADASER | biorx.si | DANBIO | ICEBIO | NOR-DMARD | Reuma.pt | ROB-FIN | RRBR | SCQM | TURKBIO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Country | Sweden | Czechia | Spain | Slovenia | Denmark | Iceland | Norway | Portugal | Finland | Romania | Switzerland | Turkey |

| All patients, second TNFi treatment (n) | 2861 | 626 | 184 | 155 | 1676 | 121 | 356 | 215 | 343 | 72 | 984 | 661 |

| Age, years | 44 (35–54) | 43 (36–51) | 48 (40–58) | 47 (40–54) | 42 (34–52) | 43 (36–52) | 42 (34–51) | 46 (38–53) | 43 (36–52) | 48 (38–56) | 45 (35–52) | 39 (33–47) |

| Male, % | 54 | 66 | 65 | 58 | 55 | 64 | 52 | 52 | 54 | 58 | 47 | 57 |

| HLA-B27 positive, % | NA | 90 | NA | 81 | 68 | — | NA | 72 | 87 | NA | 59 | 64 |

| Time since diagnosis, years, | 3 (1–8) | 9 (4–14) | 9 (4–17) | 7 (3–13) | 3 (1–8) | 5 (2–16) | 7 (2–17) | 7 (3–13) | 6 (3–12) | 4 (2–11) | 3 (1–9) | 5 (3–10) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | NA | 27 (24–30) | 28 (24–30) | 27 (24–29) | 25 (23–29) | 26 (23–28) | — | 26 (23–29) | 27 (24–30) | 27 (23–31) | 26 (23–29) | 27 (24–30) |

| Current smoking, % | 12 | 27 | 31 | 24 | 35 | 29 | 26 | 31 | — | 15 | 24 | 40 |

| Infliximab | 12 | 11 | 17 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 15 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 15 | 18 |

| Etanercept | 34 | 31 | 25 | 24 | 35 | 45 | 31 | 39 | 39 | 32 | 28 | 36 |

| Adalimumab | 35 | 26 | 29 | 34 | 30 | 26 | 20 | 31 | 42 | 24 | 29 | 27 |

| Certolizumab pegol | 5 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 4 | 10 |

| Golimumab | 14 | 25 | 24 | 27 | 12 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 13 | 22 | 24 | 9 |

| CRP, mg/l | 5 (2–14) | 13 (4–30) | 3 (1–3) | 6 (1–19) | 5 (1–12) | 5 (2–10) | 4 (1–9) | 8 (3–20) | 5 (3–11) | 21 (5–39) | 5 (1–9) | 9 (3–28) |

| ASDAS | 3.1 (2.3–3.7) | 3.6 (2.6–4.3) | — | — | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | — | — | 3.4 (2.6–4.1) | NA | 3.8 (3.0–4.7) | 3.1 (2.3–3.7) | 3.2 (2.5–3.9) |

| BASDAI (mm) | 55 (38–71) | 55 (38–71) | 51 (36–70) | 64 (43–74) | 62 (45–75) | 52 (40–69) | 51 (31–69) | 58 (33–72) | NA | 53 (40–72) | 55 (38–68) | 44 (26–60) |

| BASFI (mm) | 39 (21–62) | 44 (28–64) | NA | 58 (33–73) | 51 (30–71) | 40 (25–59) | NA | 54 (36–74) | NA | NA | 35 (15–59) | 31 (15–56) |

| BASMI | NA | NA | NA | NA | 30 (10–50) | — | NA | 42 (29–53) | NA | NA | 20 (10–30) | 40 (20–60) |

| Physician global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 30 (20–45) | 50 (25–65) | NA | — | 23 (10–40) | 40 (15–57) | 35 (23–47) | 40 (29–50) | 22 (9–43) | NA | 40 (30–50) | 29 (10–50) |

| Patient global score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 60 (40–77) | 60 (40–80) | — | — | 72 (52–86) | 60 (37–80) | 59 (34–75) | 60 (41–76) | 46 (18–69) | 70 (50–80) | 60 (40–80) | 58 (40–70) |

| Pain score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 60 (39–77) | 60 (40–75) | NA | 70 (50-80) | 67 (46–81) | 62 (43–78) | 54 (34–72) | NA | 48 (23–71) | 70 (50–80) | 60 (40–80) | 59 (40–70) |

| Fatigue score (VAS 0–100 mm) | 63 (38–80) | 60 (40–75) | NA | NA | 72 (51–85) | 63 (40–79) | 60 (34–80) | NA | NA | 70 (50–80) | 60 (50–80) | 53 (30–70) |

| 12-month drug retention rate | 71 (69–73) | 83 (80–86 | 78 (72–85) | 71 (64–78) | 64 (62–66) | 79 (72–87) | 52 (47–58) | 79 (74–85) | 86 (83–90) | 90 (83–99) | 68 (65–71) | 82 (79–85) |

| 6-month ASDAS-ID rate, % (crude/LUNDEX) | 27/19 | 31/25 | — | — | 17/12 | — | — | 15/13 | NA | — | 14/11 | 22/18 |

| BASDAI <40 mm rate at 6 months, % (crude/LUNDEX) | 58/42 | 77/63 | — | 54/44 | 50/34 | — | 59/38 | 53/44 | NA | — | 47/35 | 75/60 |

| BASDAI <20 mm rate at 6 months, % (crude/LUNDEX) | 32/23 | 45/37 | — | 16/13 | 25/17 | — | 33/21 | 25/21 | NA | — | 20/15 | 43/34 |

Data are as observed, median (IQR) or percentage of available observations; cells are marked with ‘—’ if n < 50; values were converted to mm for registries using numeric rating scale.

AE: adverse events; ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score with CRP; ASDAS-ID: ASDAS inactive disease; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Function Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BMI: body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; LOE: lack of efficacy; NA: not available; TNFi: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS; visual analogue scale.

Retention rates

Overall, the 12-month retention rate was 71% (95% CI: 70–72%) for the second TNFi and 71% (69–72%) for the third TNFi. The corresponding retention rates at 6 months were 81% (80–81%) and 81% (79–82%) for second and third TNFi treatment, respectively, and 63% (62–64%) and 61% (59–63%) at 24 months.

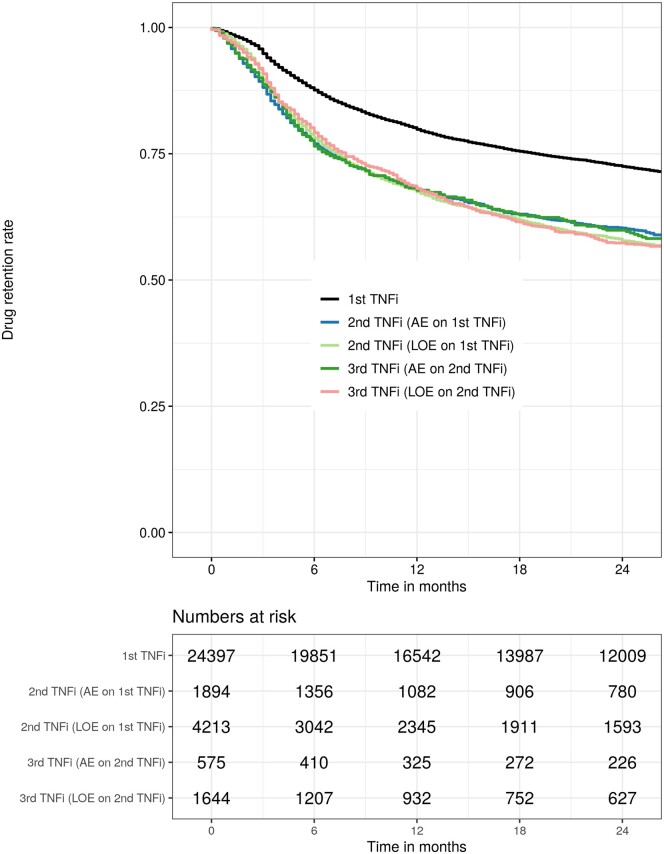

The 12-month retention rates for patients who had stopped the previous TNFi due to AE or LOE were 68% (66–70%) and 67% (66–69%) for the second and 68% (64–72%) and 68% (66–71%), respectively, for third TNFi treatment course (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Twelve-month retention rates for the second TNFi treatment in patients who withdrew due to LOE less than 26 weeks on the preceding TNFi were 58% (55–61%) vs. 71% (69–73%) (P < 0.001) for those who stayed on the preceding TNFi for 26 weeks or longer. The corresponding 12-month retention rates for the third TNFi treatment series were 64% (60–68%) vs. 71% (68–74%) (P = 0.36). Drug retention rates in the individual registries are presented in Table 4 and Supplementary Table S2 (available at Rheumatology online).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves (top) showing drug retention rates up to 24 months for first TNFi [19], for second (adverse events (AE) or lack of efficacy (LOE) on first TNFi) and third TNFi (AE or LOE on second TNFi). The table (bottom) shows the number of patients who were still being treated at the corresponding time points

Remission and low disease activity rates

The overall crude ASDAS inactive disease rates at 6 months were 23% for patients receiving a second TNFi, and 16% for patients receiving their third TNFi (Table 3). Available data are presented in Supplementary Table S3 (available at Rheumatology online). In patients receiving their second TNFi due to AE or LOE on the first TNFi, the crude ASDAS inactive disease rates at 6 months were 27% and 17% (P < 0.001). In patients receiving their third TNFi due to AE or LOE on the second TNFi, the crude ASDAS inactive disease rates at 6 months were 19% and 13% (P = 0.20). (Table 3). Crude rates for BASDAI <40 mm and <20 mm and LUNDEX adjusted rates for all remission criteria are presented in Table 3. The crude 6-month rates for ASDAS inactive disease for the second TNFi treatment for patients who withdrew due to LOE before 26 weeks on the preceding TNFi were: 12% vs 19% (P = 0.26) for those who stayed on the previous TNFi for 26 weeks or longer. Corresponding rates for the third TNFi treatment series were: 14% vs 14%. The 6-month ASDAS inactive disease rates in the individual registries are presented in Table 4 and Supplementary Table S1 (available at Rheumatology online).

Discussion

This study investigated the real-world effectiveness of second and third TNFi treatment courses in patients with axSpA based on data from 12 European registries participating in the EuroSpA research collaboration. We found a similar one-year retention rate of 71% in 8254 s and 2939 third TNFi treatment courses, while remission rates after 6 months of treatment were higher for the second (23%) than the third (16%) TNFi series.

Previous studies investigating drug retention rates in real-world data for axSpA patients initiating their second TNFi have reported 2-year retention rates of 47% (Danish DANBIO, n = 432) [9], 60% (Norwegian NOR-DMARD, n = 77) [7] and 72% (Finnish ROB-FIN, n = 123) [10], while rates after one year were 60% in a retrospective monocenter study of 222 patients [26]. Data regarding drug retention for a third TNFi are limited. In a literature review of patients with axSpA who switch TNFis, nine of the 21 included studies reported switches to a third TNFi with patient numbers ranging from 2 to 137, corresponding to 1–10% of the number of patients initially included [12]. A two-year drug retention rate of 49% (which was similar to the retention rate of the second TNFi) was found in the single study that reported retention of the third TNFi [9].

We found that approximately one in four patients receiving a second TNFi compared with one in six receiving a third TNFi, achieved remission. To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate remission rates in second and third TNFi treatment series, but decreasing response rates across treatment series [first (54%), second (37%) and third (30%)] have been reported from the DANBIO registry using a reduction in BASDAI of at least 50% or >20 mm as response criteria [9, 27]. Similar decreases in treatment responses, albeit, from first to second TNFi treatment series have been reported from the NOR-DMARD and the ROB-FIN registries [7, 10].

The similar treatment retention rates for the second and third TNFi despite a lower rate of remission on the latter, may reflect the fact that patients tend to stay longer on the drug as treatment options are fewer after the second than the first TNFi treatment course. In more recent years, shorter treatment durations may be expected following the emergence of alternative therapeutic options. It is not known, however, if such trends would impact second and third treatment courses differently [6, 28]. To our knowledge, the only other study comparing second and third TNFi treatment courses in patients with AS reported similar retention rates; however, the study was from 2013 when TNFi was the only available bDMARD for the treatment of SpA [9].

Our findings are thus in line with prior studies on switches from a first to a second TNFi treatment, while adding considerable weight to the scarce existing knowledge on switches from a second to third TNFi. The study supports the concept that not only the first but also a second switch may be beneficial in some patients, although the remission rates are low after the second switch.

We expected switching due to lack of efficacy of the preceding TNFi to be associated with poorer treatment response to the subsequent TNFi compared with switching due to AE, as the mechanism of action had not yielded the anticipated treatment response. However, our results were not consistent, as 12-month drug retention rates were independent of the reason for withdrawal from the preceding TNFi, while remission rates were higher, if the reason for switching was AE vs LOE on the preceding TNFi, but in the second series only. Patients who failed the second TNFi due to LOE only rarely achieved remission from a third TNFi treatment (13%), but somewhat surprising, the drug retention rates for the third treatment was similar to that of the second, perhaps due to lower expectations regarding the clinical response. Our further stratification into primary vs secondary non-responders also yielded inconsistent results, as the secondary non-responders (to the first but not the second TNFi) had higher retention rates but similar remission rates compared with primary non-responders. These findings are only partly in concordance with previous studies e.g. from the Rheumatic Diseases Portuguese Register (Reuma.pt) and the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Cohort (SCQM) that have supported a distinction between primary and secondary non-response to the first TNFi based on differences in rates for both ASDAS inactive disease and drug retention [8, 13, 14]. In the 2019 ACR guidelines for axSpA, a switch to an IL17i in case of primary non-response to a TNFi is recommended, although the studies behind the recommendation are not investigating this specific scenario [24, 29, 30]. The 2022 ASAS/EULAR instead recommend any switch in case of failure of the first bDMARD due to lack of data for further guidance [17].

Regarding switches from the second to third TNFi series, our study did not show any statistically significant differences in treatment responses according to discontinuation reason, and to our knowledge, no studies have performed such analyses previously. It could be speculated that the treatment decision after a second TNFi series is more likely to be influenced by a mix of several factors and not only by the reason for discontinuation of the previous TNFi. For instance, a patient who has experienced primary non-response or AE on two TNFi may be more likely to be switched to another mode of action than a patient who has experienced secondary non-response on the first and an AE on the second. Therefore, we find that more firm conclusions on the third TNFi treatment series would need to be based on a study performed in a controlled setting.

Across registries, we found that both retention and remission rates differed markedly; considerable heterogeneity in baseline characteristics, including disease activity, was observed and may have contributed to the differences in outcomes. Moreover, differences in prescription patterns and national guidelines regarding the threshold for switching from one TNFi to another may have impacted the results [19, 31].

Future studies should investigate whether inter-country differences in outcomes can be explained by differences in demographic, clinical, imaging or serological markers, and factors of predictive value for remission and drug retention should be explored. Detailed information on national treatment guidelines and access to biological drugs should be collected to investigate their influence on patient characteristics, retention, and remission rates. For instance, it may be speculated that a relatively easy access to bDMARDs and a tendency to focus on treat-to-target strategies may lead to more rapid treatment cycling with less disease activity at treatment start and lower retention rates. Moreover, since bDMARDs seem more effective in bionaive vs bio-experienced patients [8, 32, 33], rheumatologists may increasingly prefer switching to a new mode of action instead of switching within the same drug class, although this strategy has not been investigated in a randomized controlled setting.

Strengths of this study include the high number of patients followed prospectively with data collection performed in the individual countries independently of the current study. Secondary use of the data enabled us to stratify for the reason for discontinuation of the previous TNFi in patients receiving a second or third TNFi. However, when pooling data from heterogeneous populations with different baseline characteristics, prescription patterns and national treatment guidelines, the results may no longer be representative for the single country, which is a limitation of the current approach. Moreover, selection bias based on data availability cannot be ruled out. Subjects that are compliant may visit their rheumatologist more regularly and therefore have more complete registry data. This could potentially lead to overestimation of remission rates, but this bias should affect second and third TNFi treatment courses to a similar degree.

In conclusion, in this EuroSpA study of pooled data from 12 European registries, we found that almost three quarters of axSpA patients remained on both a second and a third TNFi after one year. Retention rates were independent of the reason for withdrawal from the preceding TNFi; however, in patients with a primary non-response to the first TNF treatment, the rates were lower compared with patients with a secondary non-response. The remission rates were higher for the second than the third TNFi series, and moreover, for the second series, they were higher in patients who withdrew from the previous TNFi due to AE rather than LOE. Our findings suggest that not only a second but also a third TNFi treatment may be beneficial in some axSpA patients; however, the low remission rates in the latter highlight the need for drugs with other modes of action.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Romanian Registry of Rheumatic Diseases (RRBR) is acknowledged for contributing data to this study.

Contributor Information

Louise Linde, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; DANBIO Registry, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark.

Lykke Midtbøll Ørnbjerg, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; DANBIO Registry, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark.

Cecilie Heegaard Brahe, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark.

Johan Karlsson Wallman, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Rheumatology, Skåne University Hospital, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Daniela Di Giuseppe, Clinical Epidemiology Division, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Jakub Závada, Institute of Rheumatology and Department of Rheumatology, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic.

Isabel Castrejon, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón and Faculty of Medicine, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

Federico Díaz-Gonzalez, Department of Internal Medicine, Dermatology and Psychiatry, Universidad de La Laguna and Rheumatology Service, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, La Laguna, Spain.

Ziga Rotar, Department of Rheumatology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana and Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Matija Tomšič, Department of Rheumatology, University Medical Centre Ljubljana and Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Bente Glintborg, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; DANBIO Registry, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Bjorn Gudbjornsson, Centre for Rheumatology Research (ICEBIO), Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland and Faculty of Medicine, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Arni Jon Geirsson, Department of Rheumatology, University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Brigitte Michelsen, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; Center for treatment of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (REMEDY), Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway; Research Unit, Sørlandet Hospital, Kristiansand, Norway.

Eirik Klami Kristianslund, Center for treatment of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (REMEDY), Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

Maria José Santos, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital Garcia de Orta, Almada and Instituto Medicina Molecular, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal.

Anabela Barcelos, Department of Rheumatology, Centro Hospitalar do Baixo Vouga, Aveiro and Comprehensive Health Research Centre, NOVA Medical School, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal.

Dan Nordström, Departments of Medicine and Rheumatology, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland.

Kari K Eklund, Inflammation Center, Department of Rheumatology, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland.

Adrian Ciurea, Department of Rheumatology, University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

Michael Nissen, Department of Rheumatology, Geneva University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland.

Servet Akar, School of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Izmir, Turkey.

Lise Hejl Hyldstrup, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark.

Niels Steen Krogh, Zitelab ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Merete Lund Hetland, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Mikkel Østergaard, Center for Rheumatology and Spine Diseases, Center for Head and Orthopaedics, Copenhagen Center for Arthritis Research (COPECARE), Rigshospitalet, Glostrup, Denmark; Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Rheumatology online.

Data availability

The data in this article was collected in the individual registries and made available for secondary use through the EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network (https://eurospa.eu/#registries). Relevant patient-level data may be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author but will require approval from all contributing registries.

Funding

The EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network was financially supported by Novartis Pharma AG. Novartis had no influence on the data collection, statistical analyses, manuscript preparation or decision to submit the manuscript.

Disclosure statement: L.L.: Research grant from Novartis; L.M.O.: Research grant from Novartis; C.H.B.: Research grant from Novartis; J.K.W.: Speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer; D.D.G.: None; J.Z.: Speaker and consulting fees from Abbvie, Elli-Lilly, Sandoz, Novartis, Egis, UCB; I.C.: Speaker and/or consultancy fees from BMS, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, MSD, Pfizer, GSK; F.D.-G.: None; Z.R.: Speaker and/or consulting fees from Abbvie, Novartis, MSD, Medis, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi, Lek, Janssen; M.T.: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, Amgen, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medis, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sandoz-Lek; B.Gl.: Research grants from Pfizer, Abbvie, BMS, Sandoz; B.Gu.: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Novartis, Nordic Pharma; A.J.G.: None; B.M.: Research grant from Novartis; E.K.K.: None; M.J.S.: Speaker fees from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer; A.B.: Consulting fees from Abbvie, Lilly and Novartis, Speaker fees from Abbvie, Janssen, Novartis; D.N.: Consulting and/or speaking fees from Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; K.K.E.: Consulting fees from Amgen, Celgene, Gilag, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sobi, UCB; A.C.: Consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis; M.N.: Consulting and/or speaking fees from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssens, Novartis, Pfizer; S.A.: Speaker and consulting fees from Pfizer, Abbvie, Lilly, Novartis, UCB, Amgen, Celltrion, Sandoz; L.H.H.: Research grant from Novartis; N.S.K.: None; M.L.H.: Speaker fees from Pfizer, Medac, Sandoz and research grants from Abbvie, Biogen, BMS, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics B.V, Lundbeck Fonden, MSD, Medac, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung Biopies, Sandoz, Novartis; M.Ø.: research grants from Abbvie, BMS, Merck, Novartis and UCB and speaker and/or consultancy fees from Abbvie, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli-Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Hospira, Janssen, MEDAC, Merck, Novartis, Novo, Orion, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi and UCB.

References

- 1. Van Der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P. et al. ; Ankylosing Spondylitis Study for the Evaluation of Recombinant Infliximab Therapy Study Group. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:582–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH. et al. ; ATLAS Study Group. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2136–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juanola X, Ramos MJM, Belzunegui JM, Fernández-Carballido C, Gratacós J.. Treatment failure in axial spondyloarthritis: insights for a standardized definition. Adv Ther 2022;39:1490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Krogh NS. et al. Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years’ surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:2002–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baraliakos X, Braun J, Deodhar A. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of secukinumab 150 mg in ankylosing spondylitis: 5-year results from the phase III MEASURE 1 extension study. RMD open 2019;5:e001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J. et al. ; MEASURE 2 Study Group. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17a inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lie E, Van Der Heijde D, Uhlig T. et al. Effectiveness of switching between TNF inhibitors in ankylosing spondylitis: data from the NOR-DMARD register. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rudwaleit M, Van den Bosch F, Kron M, Kary S, Kupper H.. Effectiveness and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis and history of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Krogh NS. et al. Clinical response, drug survival and predictors thereof in 432 ankylosing spondylitis patients after switching tumour necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heinonen AV, Aaltonen KJ, Joensuu JT. et al. Effectiveness and drug survival of TNF inhibitors in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective cohort study. J Rheumatol 2015;42:2339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navarro-Compán V, Plasencia-Rodríguez C, de Miguel E. et al. Switching biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a systematic literature review. RMD Open 2017;3:e000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deodhar A, Yu D.. Switching tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ciurea A, Exer P, Weber U. et al. ; Rheumatologists of Swiss Clinical Quality Management Program for Axial Spondyloarthritis. Does the reason for discontinuation of a first TNF inhibitor influence the effectiveness of a second TNF inhibitor in axial spondyloarthritis? Results from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management Cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manica SR, Sepriano A, Pimentel-Santos F. et al. Effectiveness of switching between TNF inhibitors in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: is the reason to switch relevant? Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karlsson JA, Kristensen LE, Kapetanovic MC. et al. Treatment response to a second or third TNF-inhibitor in RA: results from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS. et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A. et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brahe CH, Ørnbjerg LM, Jacobsson L. et al. Retention and response rates in 14 261 PsA patients starting TNF inhibitor treatment - Results from 12 countries in EuroSpA. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 2020;59:1640–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ørnbjerg LM, Brahe CH, Askling J. et al. Treatment response and drug retention rates in 24 195 biologic-naïve patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating TNFi treatment: routine care data from 12 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1536–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC. et al. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1694–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, O’Hea J, Jenkinson MP.. T. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lukas C, Landewé R, Sieper J. et al. ; Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG. et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS. et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the Treatment of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Nonradiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) 2019;71:1599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kristensen LE, Saxne T, Geborek P.. The LUNDEX, a new index of drug efficacy in clinical practice: results of a five-year observational study of treatment with infliximab and etanercept among rheumatoid arthritis patients in Southern Sweden. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dadoun S, Geri G, Paternotte S, Dougados M, Gossec L.. Switching between tumour necrosis factor blockers in spondyloarthritis: a retrospective monocentre study of 222 patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:1010–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anderson JJ, Baron G, Van Der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M.. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1876–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Christiansen SN, Ørnbjerg LM, Rasmussen SH. et al. European bio-naïve spondyloarthritis patients initiating TNFi: time trends in baseline characteristics, treatment retention and response. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:3799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M. et al. ; COAST-V Study Group. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 ra. Lancet (London, England) 2018;392:2441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco-Tena C. et al. ; COAST-W Study Group. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: sixteen-week results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necr. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michelsen B, Lindström U, Codreanu C. et al. Drug retention, inactive disease and response rates in 1860 patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating secukinumab treatment: routine care data from 13 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. RMD Open 2020;6:e001280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chimenti MS, Fonti GL, Conigliaro P. et al. One-year effectiveness, retention rate, and safety of secukinumab in ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis: a real-life multicenter study. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2020;20:813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramonda R, Lorenzin M, Carriero A. et al. ; on behalf Spondyloartritis and Psoriatic Arthritis SIR Study Group “Antonio Spadaro”. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in 608 patients with psoriatic arthritis in real life: a 24-month prospective, multicentre study. RMD Open 2021;7:e001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data in this article was collected in the individual registries and made available for secondary use through the EuroSpA Research Collaboration Network (https://eurospa.eu/#registries). Relevant patient-level data may be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author but will require approval from all contributing registries.