Abstract

Cerebral oedema is associated with morbidity and mortality after traumatic brain injury (TBI)1. Noradrenaline levels are increased after TBI2–4, and the amplitude of the increase in noradrenaline predicts both the extent of injury5 and the likelihood of mortality6. Glymphatic impairment is both a feature of and a contributor to brain injury7,8, but its relationship with the injury-associated surge in noradrenaline is unclear. Here we report that acute post-traumatic oedema results from a suppression of glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow that occurs in response to excessive systemic release of noradrenaline. This post-TBI adrenergic storm was associated with reduced contractility of cervical lymphatic vessels, consistent with diminished return of glymphatic and lymphatic fluid to the systemic circulation. Accordingly, pan-adrenergic receptor inhibition normalized central venous pressure and partly restored glymphatic and cervical lymphatic flow in a mouse model of TBI, and these actions led to substantially reduced brain oedema and improved functional outcomes. Furthermore, post-traumatic inhibition of adrenergic signalling boosted lymphatic export of cellular debris from the traumatic lesion, substantially reducing secondary inflammation and accumulation of phosphorylated tau. These observations suggest that targeting the noradrenergic control of central glymphatic flow may offer a therapeutic approach for treating acute TBI.

TBI affects around 55–74 million people per year worldwide9,10. Acute TBI ranges in severity from mild to fatal, and can develop into chronic traumatic encephalopathy—a condition that is characterized by cognitive decline, behavioural changes and the intracerebral accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau protein11,12. A particularly harmful complication of TBI is cerebral oedema, which increases the risk of death tenfold1 and worsens the functional out comes of patients who survive the initial injury. Recent advances have broadened our understanding of the pathophysiology of brain oedema. Noradrenaline (NA) levels are significantly increased in patients with TBI2–4, and the degree of NA elevation correlates with the severity of injury5, functional outcome and mortality6. NA is secreted by brainstem nuclei, including the locus coeruleus, whereas the adrenal medulla is the primary source of NA in the blood13. As NA suppresses fluid transport within the brain14, we posited that broad adrenergic inhibition after TBI might help to restore the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and resolve oedema.

Under physiological conditions, CSF is partially or fully drained by outflow pathways that include the meningeal and cervical lymphatic vessels15,16, which return fluid through the thoracic duct to the venous circulation14,17. Blockade of meningeal or cervical lymphatic vessels accelerates the deposition of amyloid-, tau and synuclein in rodent disease models15,18,19 and worsens brain oedema as well as infarct volume in stroke20. In a mouse model of TBI, we found that excessive levels of NA suppress glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow and debris transport, resulting in cerebral oedema, and that this process can be attenuated by adrenergic inhibition.

Adrenergic inhibition prevents oedema

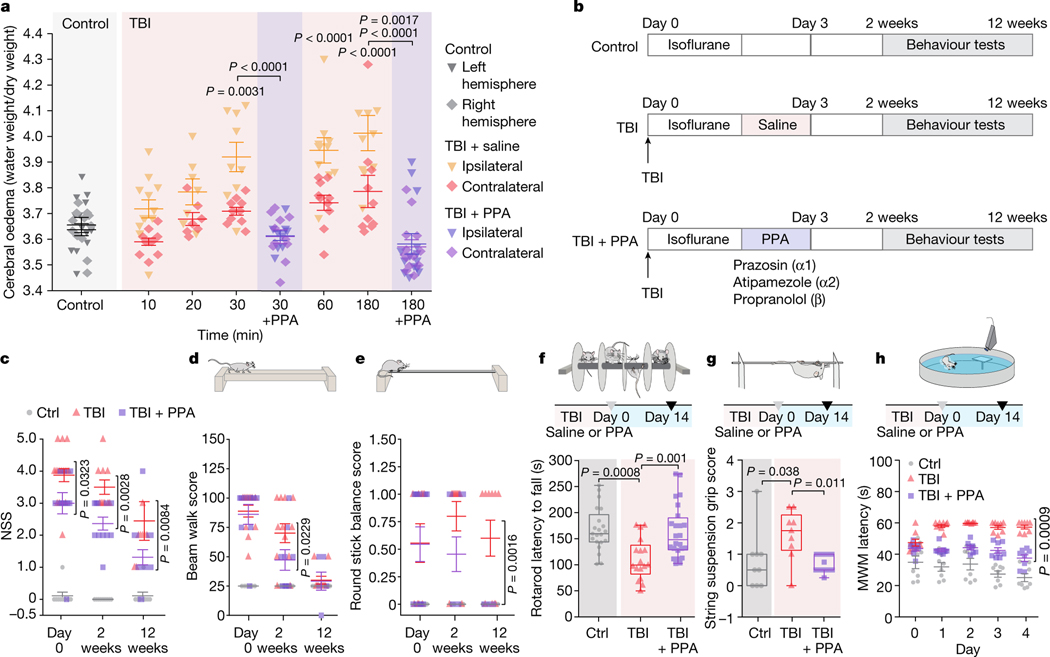

We first assessed the dynamics of cerebral oedema and CSF influx in the ‘hit and run’ TBI model in mice8. A significant increase in brain water content was evident 30 min after injury in the ipsilateral hemisphere and at 180 min in the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 1a). TBI suppresses glia-dependent CSF flow through the perivascular spaces, which defines glymphatic flow8. To improve brain fluid transport, we broadly inhibited adrenergic receptors, owing to the known role of adrenergic signalling in inhibiting glymphatic transport14. The pharmacological cocktail (hereafter, PPA) included prazosin (an -adrenergic receptor antagonist), atipamezole (an -adrenergic antagonist) and propranolol (a broad -adrenergic receptor antagonist). PPA was administered14 intraperitoneally (i.p.) to mice shortly after they were exposed to a hit-and-run head injury8. Notably, PPA treatment almost entirely eliminated cerebral oedema (Fig. 1a). Among the separate components of PPA, prazosin and propranolol individually reduced oedema to some extent, but the beneficial effect was sharply potentiated by combining the three NA receptor antagonists (Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Administration of PPA 24 h after injury also reduced cerebral oedema significantly (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1 |. Pan-adrenergic receptor inhibition eliminates oedema and improves functional outcomes after TBI.

a, The kinetics of cerebral oedema in the mouse brain with or without TBI and PPA treatment (n = 81 mice) was quantified in ipsilateral (triangles) and contralateral (diamonds) hemispheres at 0 min (n = 12), 10 min (n = 11), 20 min (n = 7), 30 min (n = 9), 60 min (n = 10) and 180 min (n = 10) after injury. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (F7,146 = 19.55, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test in the ipsilateral hemispheres (control (ctrl) versus 30, 60 and 180 min, P = 0.0031, P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively) and contralateral hemisphere (control versus 180 min, P = 0.0107); ipsilateral versus contralateral hemisphere comparisons: 30 min (P = 0.003), 60 min (P = 0.003) and 180 min (P = 0.0007); TBI + saline and TBI + PPA treatment comparison: 30 min (n = 9 mice each; ipsilateral, P < 0.0001; contralateral, P = 0.812) and 180 min (n = 10 and 13 mice, respectively; ipsilateral, P < 0.0001; contralateral, P = 0.0017). b, Experimental schematic for behavioural assessment. c–e, Neurological severity score (c; NSS). n = 97 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (F2,88 = 2.88, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test: TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA, P = 0.0323 (n = 12 each), P = 0.0028 (n = 12 each) and P = 0.0084 (n = 10 and 12, respectively) at day 0 and after 2 and 12 weeks, respectively. d,e, Performance in the beam walk (d) and round stick balance (e) tests. f, Rotarod falling latency at 2 weeks after TBI with or without PPA treatment compared with the non-injured control. n = 62 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (F2,59 = 9.006, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test: control (n = 21) versus TBI + saline (n = 17) (P = 0.0008); TBI + saline (n = 17) versus TBI + PPA (n = 24) (P = 0.001). g, String suspension grip scores. n = 31 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (F2,28 = 5.43, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test: TBI + saline (n = 9) versus TBI + PPA (n = 13) (P = 0.0114). h, The Morris water maze (MWM) test was performed at 2 weeks after TBI. n = 24 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA (F8,105 = 3.625, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test: TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (P = 0.0009). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (a, c–e and h). Box plots show the lower and upper quartiles (box limits), median (centre line) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers).

Halting oedema improves recovery after TBI

Suppression of post-TBI oedema by PPA had long-term behavioural benefits; the scores for neurological function (Fig. 1c–e), rotarod performance and string suspension (Fig. 1f,g) were all significantly improved in mice that were treated with PPA, which was administered daily for 3 days (Fig. 1b). Spatial learning and memory, as assessed using the Morris water maze test, were significantly enhanced during post-traumatic recovery of the PPA-treated mice compared with the vehicle-injected TBI mice (Fig. 1h). Similarly, the locomotor function of PPA-treated injured animals was significantly improved 2 weeks after injury. Moreover, anxiety-like behaviours, characterized by the number and duration of freezing episodes during undisturbed ambulation, were reduced (Extended Data Fig. 1d,e). An assessment at 12 weeks after TBI revealed spontaneous recovery of locomotor function with or without PPA treatment, but anxiety-like behaviours persisted in the injured mice unless treated with PPA (Extended Data Fig. 1f).

Oedema follows glymphatic failure

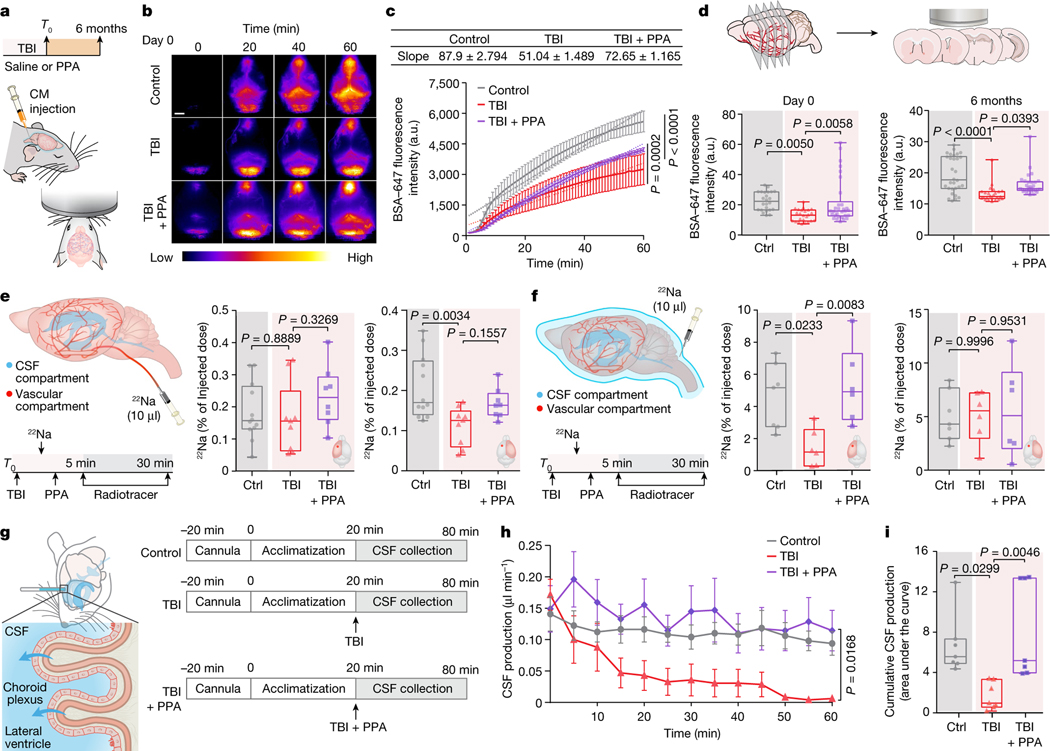

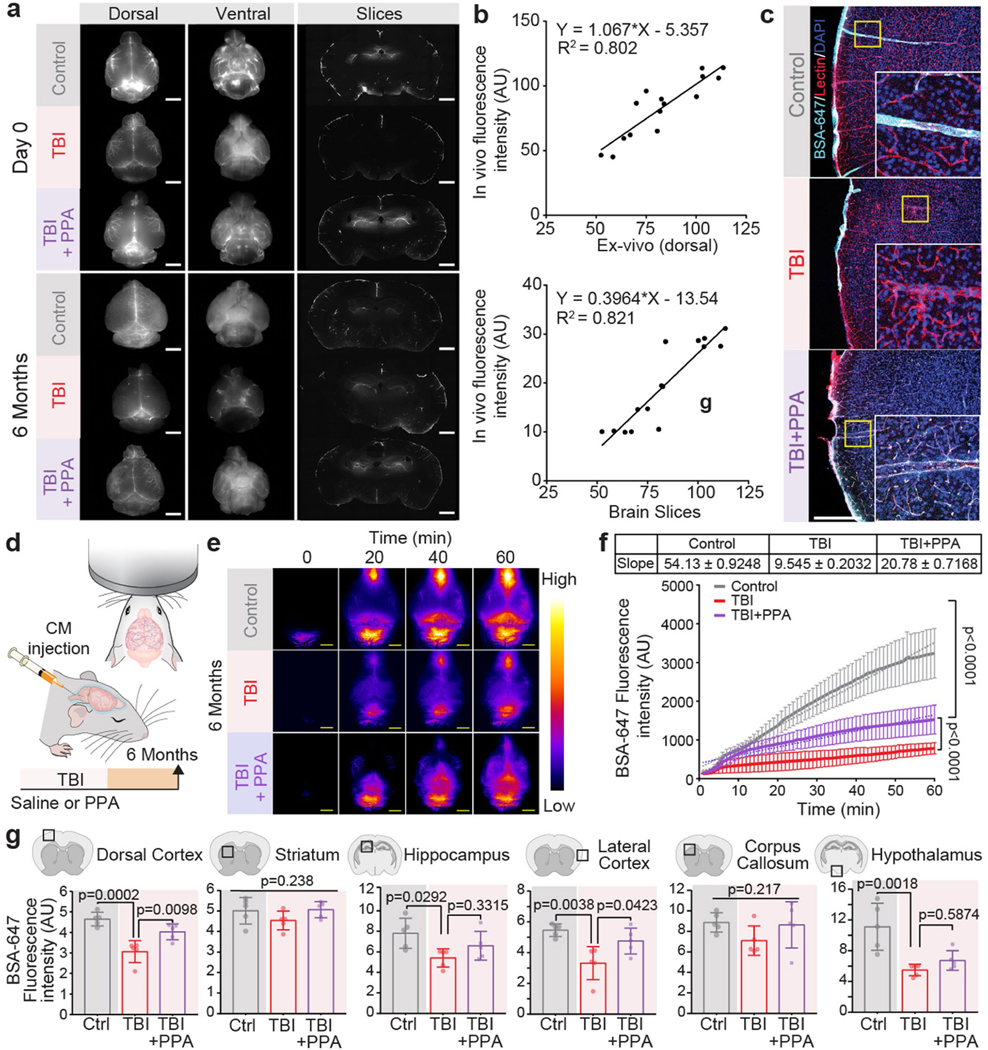

On the basis of these data, we next considered whether post-TBI oedema was a consequence of increased fluid influx from the vascular or CSF compartments or, alternatively, whether TBI might yield oedema through the suppression of brain fluid efflux. We first confirmed that TBI is associated with an acute reduction in CSF tracer transport7 (Fig. 2a–d). PPA treatment administered shortly after injury partly rescued CSF influx (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Fig. 2a). We also assessed glymphatic function 6 months after the head injury, which revealed a persistent reduction relative to that of age-matched controls (Fig. 2d (right) and Extended Data Fig. 2a,d–f). Both transcranial macroscopic imaging in vivo (Fig. 2b,c) and ex vivo analysis of CSF tracer distribution in the whole brain (Extended Data Fig. 2a) or in brain slices (Fig. 2d) suggested that TBI was linked to a long-lasting reduction in glymphatic flow. The analysis quantified fluorescence intensities of in vivo transcranial versus ex vivo dorsal images, and in vivo transcranial versus ex vivo brain slices (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Glymphatic impairment as a result of TBI was global rather than unilateral, in accordance with unilateral insertion of a small glass cannula7,21 or irradiating deeper brain regions, each of which decreases CSF inflow brain-wide22. Nonetheless, regional differences in CSF flow were identified, with the largest relative suppression of CSF influx in the dorsal cortex, lateral cortex and hypothalamus (Extended Data Fig. 2g). Moreover, high-resolution confocal microscopy analysis confirmed that TBI reduced the tracer distribution within the perivascular spaces (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2 |. Post-TBI suppression of glymphatic efflux is counteracted by pan-adrenergic inhibition.

a, Schematic of fluorescent tracer injection with or without TBI and PPA treatment. CM, cisterna magna. b,c, Transcranial time-lapse imaging (b) and quantification (c) of Alexa-fluor-647-conjugated BSA tracer (BSA–647). n = 15 mice, 5 mice per group, 60 timepoints. Statistical analysis was performed using linear regression and two-way ANOVA (F2,488 = 191.8, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; values are indicated on the graph. d, The mean pixel intensity of BSA–647 in brain slices. Group means were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; values are indicated on the graph. Day 0 (n = 78 brain slices, 5 biological replicates/mice; F2,75 = 6.77, P = 0.002) and 6 months after TBI (n = 84 brain slices; 7 (30 slices), 3 (24 slices) and 5 (30 slices) biological replicates/mice in the control, TBI + saline and TBI + PPA groups, respectively; F2,81 = 14.11, P < 0.0001). e, Schematic of the injection of the radiotracer 22Na into the vascular compartment of the brain; radioactivity is shown as the percentage of the injected dose. n = 29 biological replicates/mice (12 control, 9 TBI + saline and 8 TBI + PPA). Ipsilateral: F2,26 = 1.122, P = 0.3408; contralateral: F2,26 = 6.577, P = 0.0049. f, Schematic of the CSF compartment. 22Na was injected into the cisterna magna and radioactivity is shown as the percentage of the injected dose. n = 19 biological replicates/mice (7 control, 6 TBI + saline and 6 TBI + PPA). Ipsilateral: F2,16 = 6.97, P = 0.0067; contralateral: F2,16 = 0.0656, P = 0.9367. For e and f, group means were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; values are indicated on the graph. g, Schematic of CSF production measurement in the lateral ventricles. h,i, Quantification of time-lapsed CSF production (h) (n = 21 biological replicates/mice, 7 per group, 13 timepoints; F12,233 = 2.429, P = 0.0054) and cumulative CSF production/area under the curve (i) (F2,18 = 7.393, P = 0.0045). Group means were compared using one-way (i) or two-way (h) ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; values are indicated on the graph. For c and h, data are mean ± s.e.m. Box plots show lower and upper quartiles (box limits), median (centre line) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers); dots are biological replicates/mice. For b, scale bar, 2.5 mm.

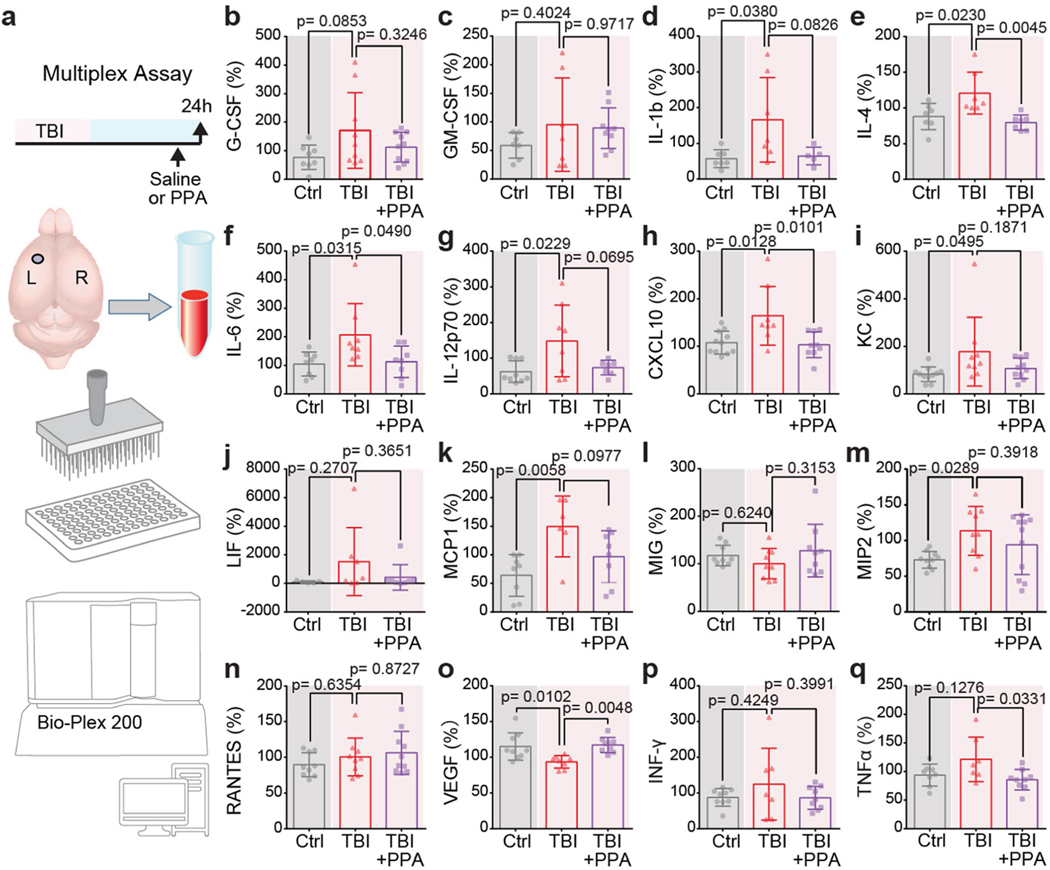

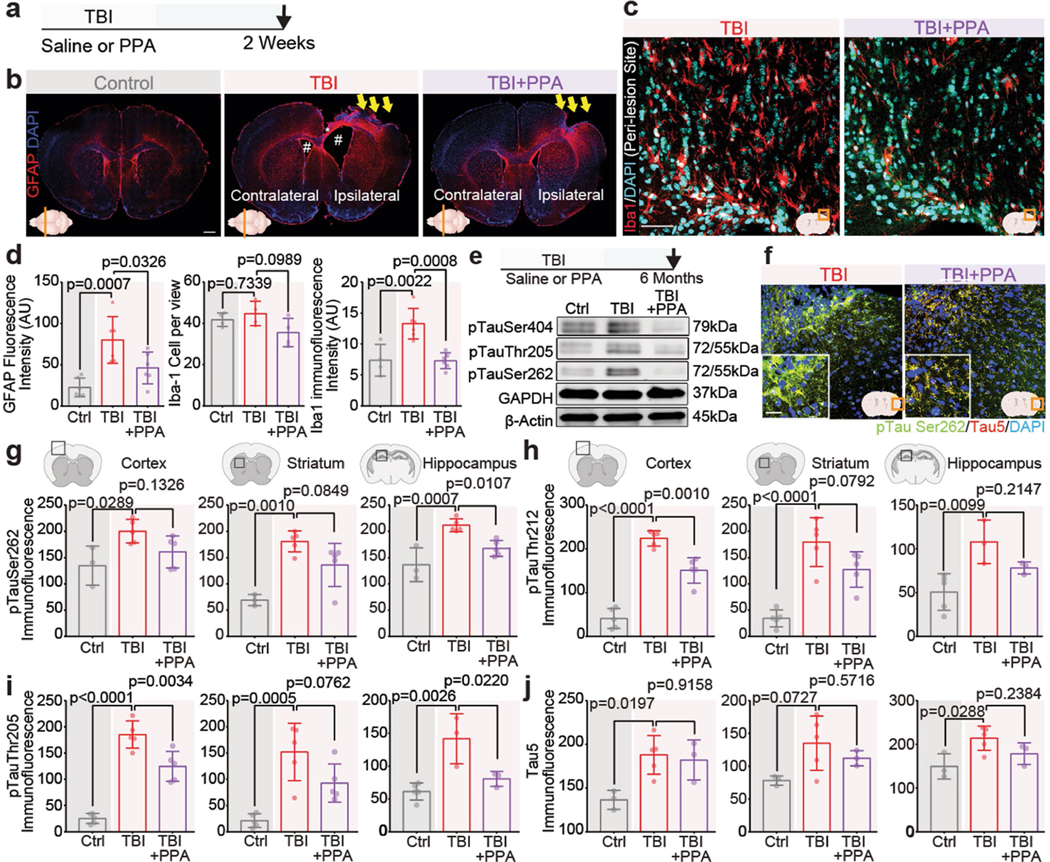

PPA attenuated phosphorylated Tau and inflammation

We next conducted a detailed analysis of the parenchymal profile of cytokines and chemokines, so as to map both the impact of TBI and the protective effects of PPA treatment. TBI induced a significant increase in the concentrations of several interleukins (IL-1, IL-4, IL-6 and IL-12p70), as well as chemokines (CXCL1 (KC), CXCL10, MCP-1 and MIP-2) in the ipsilateral hemisphere within 24 h (Extended Data Fig. 3d–i,k,m). However, a single dose of PPA proved to be sufficient to significantly reduce the levels of IL-4, IL-6 and CXCL10 (Extended Data Fig. 3).

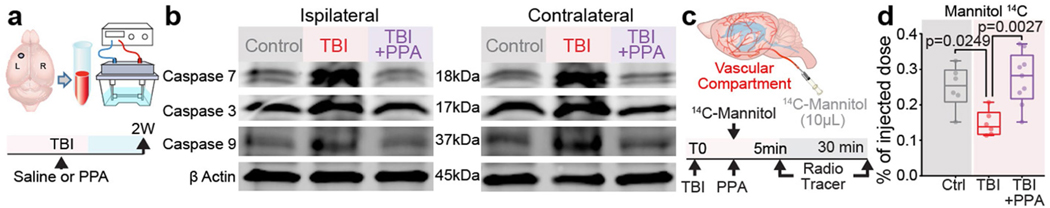

PPA treatment after TBI resulted in a marked decrease in astrogliosis and microglial activation (Extended Data Fig. 4a–d), as well as a downregulation in caspase 3, 7 and 9 (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). We further extended the study to investigate the long-term effects (6 months) of TBI (Extended Data Fig. 4e–j). Western blot analysis showed that PPA treatment after TBI suppressed the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, in particular with phosphorylation at sites Ser404, Thr205 and Ser262 (Extended Data Fig. 4e). Immunohistochemistry analysis also revealed an overall higher accumulation of total (Tau5) and phosphorylated tau (Ser262, Thr212, Thr205) in the TBI group, which was broadly decreased in the PPA-treated mice (Extended Data Fig. 4f–j).

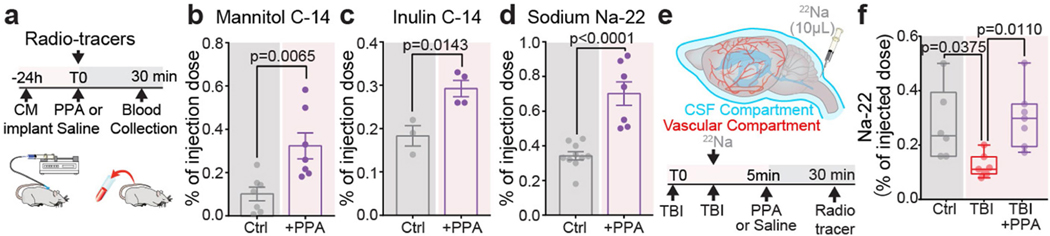

CSF retention underlies post-TBI oedema

We recently established that CSF is a major contributor to post-stroke oedema23. To assess the respective contributions of plasma transudation and CSF to post-traumatic oedema, we separately tagged the two fluid compartments by intravenous (i.v.) or intracisternal CSF administration, respectively, of radioactive sodium (22Na) shortly (<5 min) after TBI (Fig. 2e,f). The brains were collected 30 min later, and the 22Na content in each cerebral hemisphere was quantified. When blood was labelled with 22Na, no significant differences in 22Na content were noted in the ipsilateral hemispheres as compared to those of non-injured controls (Fig. 2e). By contrast, when 22Na-tagged CSF was injected into the cisterna magna (Fig. 2f), significantly less 22Na uptake occurred in the ipsilateral (injured) hemisphere of the TBI + saline group as compared to those of non-injured controls. PPA treatment increased ipsilateral 22Na uptake, mirroring the glymphatic tracer analysis and showing that TBI suppressed CSF tracer inflow, which confirms that PPA administration after TBI partially restored CSF influx (Fig. 2b–f). The experiment shown in Fig. 2 was repeated using 14C-tagged mannitol (182 Da) as the vascular tracer. Mannitol cannot cross the intact blood–brain barrier, but will enter the brain when there is a modest breach of the blood–brain barrier. We found that, as in the 22Na experiments, blood–brain barrier leakage and influx of vascular fluid did not contribute significantly to acute oedema after TBI (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Thus, compartment-selective radiolabelling together with PPA administration demonstrated that neither plasma transudation nor excessive CSF transport was responsible for TBI-induced oedema.

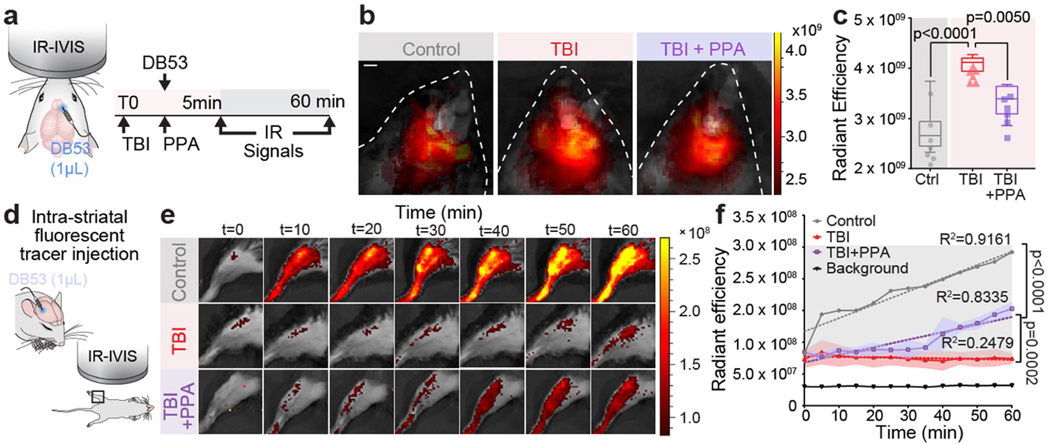

PPA rescues post-traumatic CSF efflux

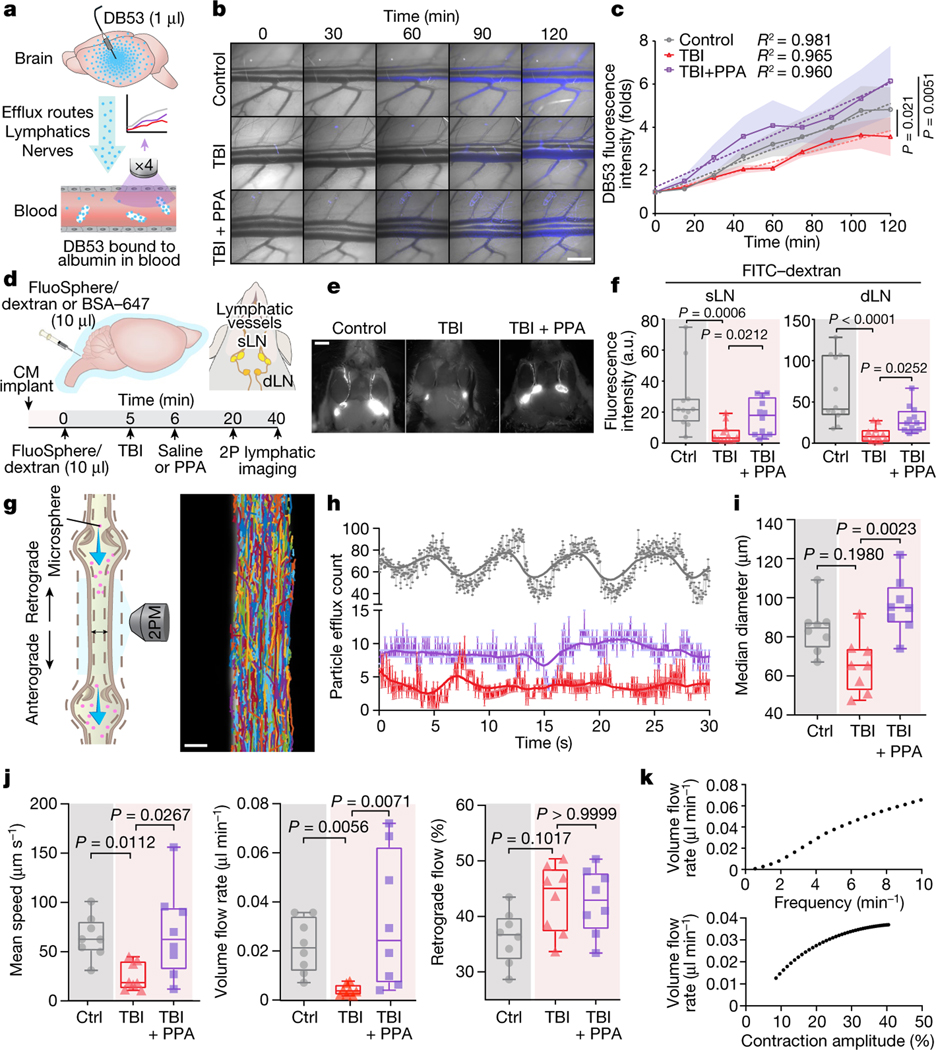

CSF is an essential component of the fluid compartment of the brain. Data characterizing the effect of TBI on CSF production is still lacking. We therefore quantified forebrain ventricular CSF production in injured and control mice. We found that TBI substantially reduced ventricular CSF production by at least 90%, and that this drop was rescued by treatment with PPA (Fig. 2g–i). However, this observation that PPA treatment increased and largely normalized CSF inflow and production after TBI was puzzling, as the same treatment efficiently reduced post-traumatic oedema. To address this paradox, we posited that PPA might globally increase fluid transport and prevent oedema formation by enhancing fluid drainage. To test this idea, we assessed the clearance of a small intracortically administered near-infrared tracer, Direct Blue 53 (DB53, 960 Da), which can be imaged through the mouse skull (Extended Data Fig. 6a). DB53 dispersed from the site of injection into the surrounding brain parenchyma of uninjured control mice. By contrast, TBI mice exhibited little spread of the tracer over the duration of observation (60–90 min). Pan-adrenergic inhibition after TBI partially restored the spread and clearance of the tracer (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). To further validate this hypothesis, we took advantage of the fact that brain solutes are ultimately exported through glymphatic and lymphatic transport to the vascular compartment and are then cleared by the liver and kidneys. DB53 diffuses freely in the brain but binds tightly to albumin when exported, and is thereby retained within the vascular compartment for durations measured in days24,25. Thus, the DB53 signal within the femoral vein correlates directly with total DB53 glymphatic and lymphatic clearance from the brain. Continuous imaging over the femoral region (Extended Data Fig. 6d) showed a steady increase in the DB53 fluorescence signal (Extended Data Fig. 6e). Mice exposed to TBI exhibited a significantly slower increase in DB53 signal, which was partly restored by PPA treatment (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Surgical exposure of the femoral artery and vein to enhance DB53 sensitivity revealed the same pattern of reduced tracer export after TBI, which was partly restored by PPA (Fig. 3a–c). Thus, pan-adrenergic antagonism by PPA treatment improved the glymphatic clearance of DB53 while eliminating post-traumatic oedema (Figs. 1a and 3c), indicating that the adrenergic suppression of glymphatic clearance causally contributes to post-traumatic brain oedema. PPA treatment resulted in enhanced efflux, which was further confirmed using a range of radiolabelled CSF tracers (mannitol, inulin and 22Na) followed by the detection of tracer radioactivity in plasma in control mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a–d) and after injury (22Na; Extended Data Fig. 7e,f).

Fig. 3 |. Fluid transport by cervical lymphatic vessels is reduced by TBI and restored after pan-adrenergic receptor inhibition.

a, Schematic of the methodology used to analyse fluid transport out of the brain and oedema clearance, using DB53 delivery and detection in the femoral vein. b, Representative images showing DB53 in the femoral vein with or without injury and PPA treatment. c, DB53 fluorescence intensity. n = 17 biological replicates/mice. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA (F8,16 = 32.04, P < 0.0001) with Sidak’s multiple-comparison test; control (n = 7) versus TBI + saline (n = 5) (P = 0.021); TBI + saline (n = 5) versus TBI + PPA (n = 5) (P = 0.0051). d, Schematic of the delivery of a mixture of Texas-Red-conjugated FluoSpheres (1 μm, 580/605 nm) and FITC–dextran (2 kDa). dLN, draining lymph node; sLN, sentinel lymph node. 2P, two-photon. e, Representative images of FITC–dextran signals detected in the CLVs and the superficial cervical lymph nodes. f, Quantification of fluorescence intensity in the cervical lymph nodes. n = 36 biological replicates/mice, 12 per group. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test; P = 0.0007 (superficial lymph nodes) and P < 0.0001 (deep cervical lymph nodes). g, Schematic of two-photon microscopy (2PM) analysis of exposed CLV and representative superimposed particle tracks (right). h, Representative time series of fluorescent particle efflux. Grey, control; red, TBI + saline; purple, TBI + PPA. i,j, The CLV median diameter (i; P = 0.0035) and the mean fluorescent particle speeds (P = 0.0060), volume flow rates (P = 0.0018) and retrograde flow percentages (P = 0.0574) (j). Group means (n = 24 biological replicates/mice, 8 per group) were compared using Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s multiple-comparison test; values are indicated on the graphs. k, Numerical simulation predicting the volume flow rate as a function of CLV contraction frequency and amplitude. For c, data are group means with continuous s.e.m. Box plots show the lower and upper quartile (box limits), median (centre line) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers). Dots represent instantaneous measurements (h) or biological replicates/mice (f, i and j). Scale bars, 1 cm (b), 2.5 mm (e) and 25 μm (g).

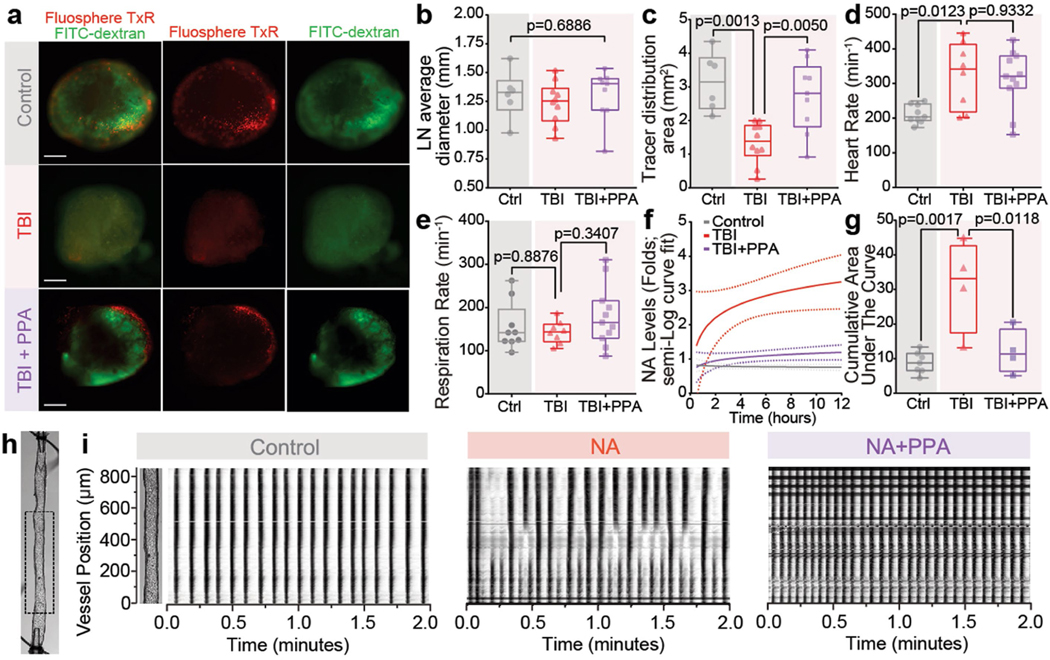

Glymphatic efflux is compromised in TBI

Adrenergic signalling is not only a critical regulator of glymphatic function14 but also a dose-dependent modulator of the activity of the peripheral lymphatic system, including that of the cervical lymph vessels (CLVs). Low levels of adrenergic stimulation enhance the frequency of lymph vessel contraction, whereas excessive or prolonged NA has the opposite effect26,27. We first confirmed that CLV drainage is suppressed after TBI28 by injecting a mixture of FITC–dextran (2 kDa) and Texas Red microspheres (1 μm diameter) into the CSF and quantifying their outflow to the superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 3d–f). A detailed analysis of tracer intensity, lymph node size and area of tracer distribution further confirmed these findings (Fig. 3e,f and Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). Time-lapse imaging revealed rhythmic contractions of the CLVs and the opening and closing of valves associated with active pumping that directed net transport of the CSF tracers (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). We tracked the microspheres by analysing high-speed two-photon in vivo recordings (Fig. 3g,h) and noted a characteristic pulsatile pattern peaking every 7–10 s (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Video 3). The microsphere efflux frequency coincided with CLV contractions, but not with cardiac or respiratory cycles (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e). Furthermore, microsphere counts were greatly reduced after TBI, but PPA partially restored the particle efflux count (Fig. 3h).

Image analysis showed that TBI slightly reduced the lymphatic vessel diameter, whereas PPA treatment increased it (Fig. 3i; P = 0.0035). Automated particle tracking velocimetry showed that the average speed was lower in the TBI group (Fig. 3j; mean ± s.e.m., 25.0 ± 4.9 μm s−1) than in the control group (64.8 ± 7.5 μm s−1), and subsequent PPA treatment restored the microsphere speed (69.2 ± 16.1 μm s−1; Supplementary Videos 3–5). On the basis of mean speed and vessel diameter, we calculated the volume flow rate for a single superficial lymph vessel. The analysis showed that lymph flow was significantly reduced in the TBI group, but restored by PPA treatment (Fig. 3j).

We next quantified valve dysfunction by measuring retrograde flow. Under physiological conditions, retrograde flow is counteracted by contraction wave entrainment, the process by which the lymphangions contract in series, resulting in the consecutive opening and closing of valves that efficiently propels fluid forward. In non-injured mice, retrograde flow averaged 36.3 ± 1.7% but increased to 43.2 ± 2.2% after TBI, and remained elevated at 42.7 ± 2.1% after PPA treatment (Fig. 3j). Furthermore, we developed numerical simulations of fluid transport through lymph vessels and obtained predictions of volume flow rates that proved to be very close to our experimental measurements (Fig. 3k).

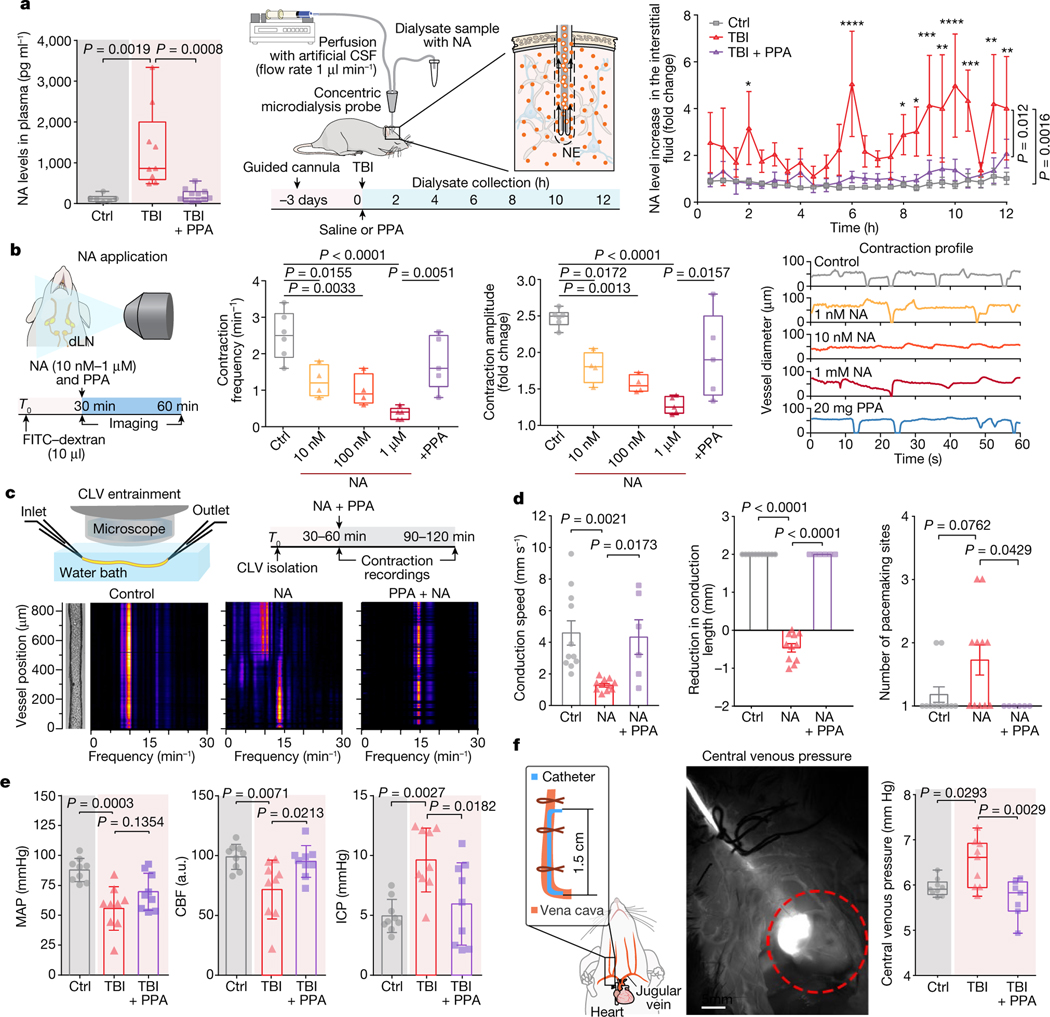

PPA suppresses post-TBI NA

We next examined how pan-adrenergic inhibition might exert its neuroprotective effects. To this end, we first quantified plasma NA levels as a function of time after injury. We found that plasma NA exhibits a sharp elevation immediately after TBI (Fig. 4a). We also monitored the temporal changes in the NA concentrations of microdialysis samples after TBI collected in the contralateral hemisphere, which revealed multiple delayed peaks in NA, which rose to levels fivefold to eightfold higher than both the baseline and the uninjured controls (Fig. 4a). These TBI-triggered increases in NA, both in the plasma and brain, were largely eliminated by PPA administration (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 8f,g). It therefore seems plausible that the excessive increases in NA observed in plasma and brain interstitial fluid (Fig. 4a) directly suppress fluid transport by the meningeal and cervical lymphatic vessels, which normally serve to return fluid from the CNS to the systemic venous circulation16,29,30. Furthermore, as adrenergic signalling is a critical negative regulator of glymphatic activity14, these data suggested that PPA might rescue glymphatic flow (Fig. 2a–d).

Fig. 4 |. Noradrenergic storm after TBI disrupts contraction wave entrainment but is prevented by PPA treatment.

a, NA levels in the plasma within 10 min of injury. n = 26 biological replicates/mice (6 control, 9 TBI + saline and 11 TBI + PPA; F2,23 = 11.67, P = 0.0003) (left). Middle, schematic of CSF sampling by microdialysis. Right, NA levels in the interstitial space. n = 15 biological replicates/mice (7 control, 4 TBI + saline and 4 TBI + PPA; F2,12 = 11.26, P = 0.0018). b, In vivo recording of contraction frequencies under various conditions; control (n = 6 mice), 10 and 100 nM (n = 4 mice each), 1 μM and PPA (n = 5 mice each). Frequencies (F4,19 = 11.89, P < 0.0001), amplitudes (F4,19 = 12.25, P < 0.0001) and representative contraction profiles with or without NA and PPA are shown. c, Schematic of the set-up used for ex vivo recording of the cervical lymphatic vessel contraction pattern and the experimental timeline (top). Bottom left, image of an isolated, pressurized superior cervical lymphatic vessel with the corresponding fast Fourier transform map. Bottom right, fast Fourier transform maps of vessels with PPA pretreatment (10 ng ml−1) before NA administration. d, Conduction and pacemaking parameters of cervical lymphatic vessels with or without NA and PPA. n = 28 vessels/mice (11 control, 11 NA and 6 NA + PPA). The conduction speed (F2,25 = 8.45, P = 0.0016), the conduction length (F2,25 = 375.5, P < 0.0001) and the number of pace-making sites (F2,25 = 4.174, P = 0.0273) are shown. e, Measurements (n = 27 biological replicates/mice, 9 per group) of MAP (F2,24 = 10.56, P = 0.0005), CBF (F2,24 = 6.613, P = 0.0052) and intracranial pressure (ICP, F2,24 = 7.847, P = 0.002). f, Central venous pressure was recorded using a jugular vein catheter (n = 25 mice; 9 control, 9 TBI + saline and 7 TBI + PPA; F2,22 = 7.762, P = 0.0028). Group means were compared using one-way (a (left), b and d–f) or two-way (a (right)) ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s (a (left)) or Tukey’s (a (right), b and d–f) multiple-comparison tests; values are indicated on the graphs. Data are group means ± s.e.m. (a) and mean ± s.e.m. (d and e). Box plots show the lower and upper quartiles (box limits), median (centre line) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers); dots show biological replicates/mice. Scale bar, 5 mm.

However, the low volume transfer by cervical lymphatic vessels in the event of TBI raises various questions of (1) whether there is less efflux and more retention of fluid because of the adrenergic spikes in the brain; (2) whether administration of PPA or its individual components to counteract noradrenergic spikes can increase the pumping efficiency of cervical lymphatic vessels; and (3) how lymphatic vessels respond to variable adrenergic stimulation ex vivo. We addressed these questions in a series of experiments.

PPA normalizes lymphatic return

To assess whether the post-traumatic failure of lymphatic transport is a direct consequence of the post-TBI adrenergic storm, different concentrations of NA were topically applied to exposed superficial cervical lymphatic vessels (Fig. 4b). NA reduced the contraction frequency and amplitude in a dose-dependent manner, and this effect was partially reversed by PPA administration (Fig. 4b). To study the effect of NA in isolation, we excised and cannulated the cervical lymphatic vessels and quantified contraction parameters under a constant internal pressure of 0.5–3 cm H2O (49–294 Pa) with or without NA treatment (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Videos 7–9). NA administration ex vivo disrupted contraction wave entrainment (Fig. 4c), which is critical for lymph propulsion against an adverse pressure gradient31, as would be the case if central venous pressure were elevated after TBI. We tracked the vessel’s outer diameter pixel by pixel and generated spatiotemporal and fast Fourier transform maps (Extended Data Fig. 8h–i and Fig. 4c) that revealed fully entrained contraction waves at conduction speeds of around 10 mm s−1, as well as a single, predominant frequency component at around 10 min−1 in the absence of NA. The addition of NA resulted in lower conduction speeds, shorter conduction lengths and multiple pacemaker sites (Fig. 4d), indicative of a loss of entrainment (Fig. 4c); these effects were all prevented by PPA treatment.

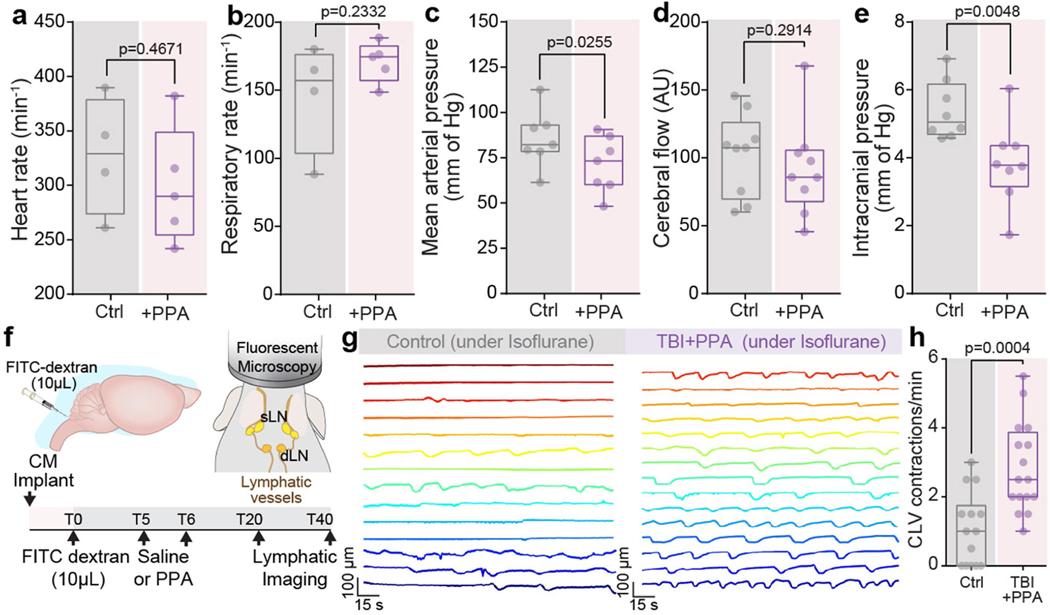

PPA normalizes cardiovascular parameters

Lymphatic return is in part regulated by central venous pressure, in that high central venous pressures across the lymphovenous valve of the thoracic duct can reduce lymphatic return to the systemic circulation32. We therefore next assessed the behaviour of a set of cardiovascular parameters in response to both TBI and its treatment. We noted decreases in both mean arterial pressure (MAP) and cerebral blood flow (CBF) in response to TBI, as well as sharp increases in both intracranial pressure and central venous pressure (Fig. 4e); each of these parameters reverted to control levels after PPA treatment (Fig. 4e,f). Analogous PPA treatment of uninjured control mice did not significantly change cardiac or respiratory rhythms, or CBF, although it did decrease intracranial pressure as well as MAP (Extended Data Fig. 9a–e), while increasing the high-amplitude contraction frequency of the cervical lymphatic vessels (Extended Data Fig. 9f–h).

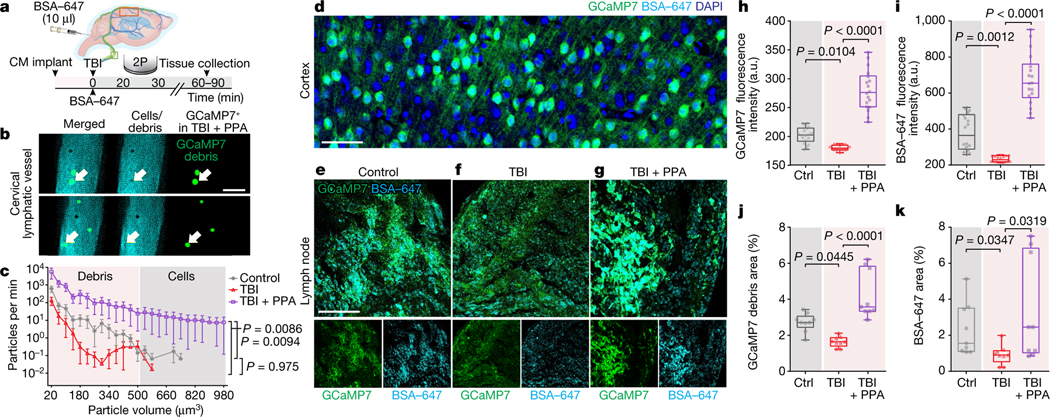

Cervical lymphatics export neural debris

While imaging the superficial cervical lymphatic vessels (Fig. 3), we observed the presence of dark, unevenly sized particles that were detectable against the bright fluorescent signal from the lymph and were most frequently observed in the TBI + PPA group (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Video 6). These particles were identified as cortical debris (Fig. 5c) by using a transgenic mouse line expressing the calcium indicator GCaMP7 in both cortical astrocytes and neurons33 (Fig. 5d). Using high-speed two-photon imaging, we were able to quantify the temporal and volumetric variations in the debris and cells (Supplementary Video 6). Subsequent histological analysis showed that the GCaMP7 signal was increased in cervical lymph nodes collected 60–90 min after TBI in the PPA-treated mice, consistent with our real-time imaging (Fig. 5e–g,h,j). A higher fluorescence signal of the CSF tracer was also noted in the lymph nodes of the PPA-treated TBI mice, compared with in the control mice and untreated mice exposed to TBI (Fig. 5e–g,i,k).

Fig. 5 |. Efflux of cells and cellular debris through CLVs in the event of TBI is neuronal in origin.

a, Mice implanted with cisterna magna cannulas received BSA–647 injection after TBI or sham hit, with or without PPA treatment, and were imaged using two-photon microscopy followed by brain and lymph node fixation. b, Dual-channel images of CLVs after TBI and PPA treatment, showing debris in green. c, Quantification of cells or debris exiting through the CLV per minute. n = 24 mice, 25 datapoints. Group means were compared using two-way ANOVA (F24,525 = 3.258, P < 0.0001) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test; control (n = 9) versus TBI + saline (n = 7) (P = 0.975); TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (n = 8) (P = 0.0086). d, GCaMP7 expression in cortical neurons and astrocytes. n = 3 biological replicates/mice, multiple slices per mouse. e–g, Lymph node slices were imaged using confocal microscopy (×40/1.4 NA, Olympus FV3000) for mice in the control (e), TBI (f) or TBI + PPA (g) groups. h, GCaMP7 green fluorescence intensity. n = 27 mice, 9 mice or 18 lymph nodes per group. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests (P < 0.0001) with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test; control versus TBI + saline (P = 0.0104); TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (P < 0.0001). i, BSA–647 fluorescence intensity. n = 27 mice, 9 mice or 18 lymph nodes per group. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests (P < 0.0001) with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test; control versus TBI + saline (P = 0.0012), TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (P < 0.0001). j, The total debris area was computed by thresholding GCaMP7 green images. n = 27 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests (P < 0.0001) with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test; control versus TBI + saline (P = 0.045); TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (P < 0.0001). k, The total debris area was computed by thresholding BSA–647 images. n = 27 mice. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis tests (P = 0.0135) with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test (P < 0.0001); control versus TBI + saline (P = 0.035); TBI + saline versus TBI + PPA (P = 0.032). For c, data are group means ± continuous s.e.m. Box plots show the lower and upper quartiles (box limits), median (centre line) and minimum to maximum values (whiskers). Scale bars, 50 μm.

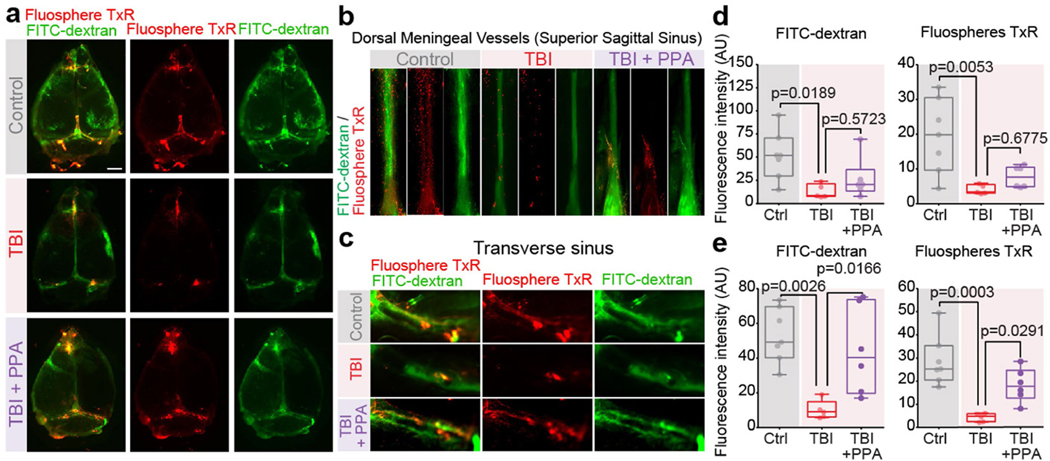

PPA rescued meningeal lymphatic drainage

Several studies have reported that meningeal lymphatic vessels are chiefly responsible for collecting brain waste before emptying into cervical lymphatic vessels15,29. Using two different CSF tracers, FITC–dextran (2 kDa) and Texas Red microspheres (1 μm), followed by quantitative analysis of tracer distribution in the meningeal lymphatic vessels adjacent to the superior sagittal sinus and transverse sagittal sinus in dural whole mount, we noted significantly less meningeal tracer efflux in the TBI group compared with in the uninjured controls. PPA treatment then rescued the tracer uptake by meningeal lymphatic vessels in the transverse sagittal sinus, although not in the superior sagittal sinus (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Discussion

Our data indicate that cerebral oedema after TBI is the result of neither vascular fluid transudation nor excessive CSF influx but is rather a consequence of impaired fluid efflux through the glymphatic system and its associated lymphatic drainage. We found that injury-associated abrogation of fluid drainage is under adrenergic control, such that interstitial fluid homeostasis could be rescued by broad adrenergic inhibition. By injecting fluorescent microspheres into the CSF, and then quantifying their movement through cervical lymphatic vessels based on particle tracking velocimetry, we obtained quantitative measurements of CSF drainage under multiple conditions. The analysis demonstrated that noradrenergic receptor inhibition after TBI boosted the lymphatic export of fluid, macromolecular proteins and cellular debris, and served to sharply reduce the consequent neuroinflammation, tau accumulation and cognitive loss compared with untreated mice.

Although our data suggest that PPA treatment improves functional recovery by resolving oedema, NA receptors are broadly expressed, and a direct effect of PPA on other cell types cannot be excluded34. Clinically, NA levels rise significantly after TBI and correlate positively with the severity of injury and mortality5,6. We confirmed these observations in the hit-and-run TBI model, which, in contrast to other rodent models of TBI, avoids the prolonged use of anaesthesia, therefore better replicating typical clinical circumstances (Fig. 4a). Anaesthesia is increasingly recognized for its ability to alter not only neural activity but also brain fluid flow35, perhaps by the potent inhibition of adrenergic signalling by most anaesthetic regimens, in particular those with central -adrenergic agonism36–38. Despite the increase in NA, which acts as a potent vasoconstrictor36,38, neither the MAP nor CBF increased after TBI. Instead, a significant decrease in MAP was noted (Fig. 4e), supporting the clinical observation that systemic hypotension is common after TBI39. Note that, although the systemic administration of NA improves cerebral perfusion pressure acutely, its ultimate beneficial impact on the neurological outcome has yet to be established40. Indeed, the risks of NA administration to patients with TBI include but are not limited to reduced end-organ perfusion, tissue hypoxia and impaired tissue healing and neuronal recovery41. Similarly, another study suggests that clinically infused NA influences platelets, possibly promoting microthrombosis formation, which induces additional damage. This exhibited platelet hypersusceptibility to NA coincides with increased intracranial pressure42. The evidence also suggests that NA, although raising blood pressure, may reduce cerebral oxygenation40.

By contrast, NA antagonist administration improved prognoses in the treatment of coma and has been linked to more rapid recovery and decreased mortality after TBI43,44. Inhibition of the -adrenergic receptor helps to alleviate delayed post-TBI symptoms of insomnia and nightmares after trauma45,46, while early treatment with receptor antagonists may reduce the chances of post-traumatic seizures47,48. Although these previous studies have all reported a beneficial effect of inhibition of individual adrenergic receptors after TBI, none had pinpointed the role of the adrenergic storm after TBI in modulating CSF fluid flow or the importance of restoring the latter to clinical outcome.

It was previously observed23 that a rapid influx of CSF was responsible for the initial oedema that developed in a model of focal stroke. The complete blockage of the middle cerebral artery triggered a rapid wave of spreading ischaemia, which constricted the surrounding vasculature, and thereby accelerated the influx of CSF from the perivascular space into the tissue parenchyma. In contrast to regions of ischaemic stroke, CBF is reduced by only 25% after TBI (Fig. 4e), so its associated tissue oedema develops at a slower pace. As oedema after TBI is largely a consequence of the reduced fluid and solute clearance that attends adrenergic storm, it therefore lends itself to treatment by adrenergic receptor inhibition.

Efflux of CSF to the cervical lymph nodes is reduced in the event of TBI28. In that regard, we confirmed that ex vivo NA administration to excised and cannulated cervical lymphatic vessels led to the loss of contraction wave entrainment (Fig. 4c), which was reversed by PPA treatment. Finally, central venous pressure, which is increased in TBI49 and in the hit-and-run TBI model (Fig. 4f), may have a critical role. The thoracic and right lymphatic ducts, which contain all the effluents from the brain, empty into the subclavian veins, in a process that is dependent on the pressure difference between the two, which regulates the patency of the lympho-venous valves. If increased central venous pressure prevents that valve from opening, fluid will be retained in lymphatic vessels, and lymphatic backflow will therefore increase, resulting in glymphatic stasis, as observed here (Figs. 3 and 4).

The accumulation of tissue and cellular debris has been noted to impede repair across a broad range of injuries and insults50. Our report therefore extends the current literature by showing that, after TBI and its attendant structural damage, cellular components and contents are released into the brain interstitium and are then, in part, cleared by bulk flow through the glymphatic and cervical lymphatic systems. We directly observed cellular debris in cervical lymphatic vessels and, using a transgenic reporter line (GCaMP7), established its neuronal and glial cellular origin (Fig. 5). The post-TBI suppression of glymphatic and lymphatic efflux resulted in the retention of this debris within the neuropil, whereas PPA treatment facilitated its efflux. Such clearance substantially reduced post-TBI inflammation, with reductions in astrogliosis, microglial activation and cytokine accumulation, the latter as evidenced by lower post-traumatic levels of IL-1, IL-4 and IL-67 (Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4).

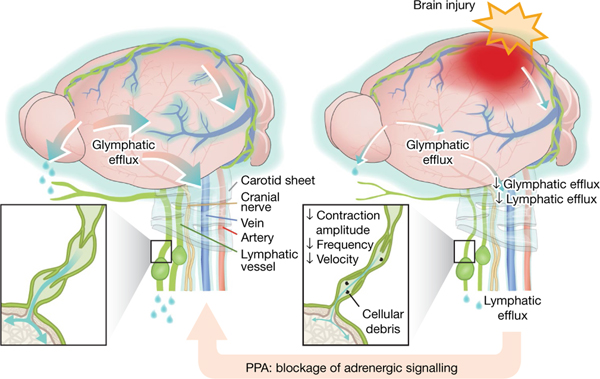

In conclusion, these data advance our understanding of those components of brain fluid transport that contribute to TBI-induced cerebral oedema (Fig. 6). A traditional concept of physiology is that brain fluid homeostasis is locally regulated by an interchange of fluid between the vascular compartment and brain parenchyma. Yet, the data presented here show that intravascular fluid transudation does not contribute significantly to oedema formation after acute TBI, which is instead caused by the noradrenergic interruption of glymphatic and lymphatic drainage. TBI-associated interference with the glymphatic and lymphatic system, whether through an adrenergic storm or elevated intracranial or central venous pressure, worsens oedema and causes the retention of neural debris, consolidating glymphatic occlusion and leading to a feed-forward exacerbation of the initial insult. Our findings suggest that this cascade of events can be reversed by pan-adrenergic inhibition, with the subsequent improvement and normalization of both sensorimotor and cognitive functions in the injured mouse brain.

Fig. 6 |. Brain fluid export is compromised by TBI and counteracted by pan-adrenergic inhibition.

CSF exchanges with interstitial fluid, is collected along perivenous spaces (shown as light blue) and drains out through meningeal lymphatic vessels and soft tissue surrounding nerves and vessels (left). Right, brain injury suppresses brain fluid export and results in tissue swelling. The reduced outflow in response to injury is attributed to an adrenergic storm, which reduces glymphatic fluid transport as well as cervical lymphatic vessel contraction frequency and amplitude, disrupts entrainment and reduces the downstream volume transfer efficiency. Adrenergic inhibition alleviates these changes and eliminates acute oedema. Treatment with adrenergic receptor antagonists also facilitates the clearance of cellular debris, reducing neuroinflammation and improving functional recovery.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06737-7.

Methods

Animals

Wild-type C57BL/6 male and female mice, aged 8–12 weeks, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. C57BL/6-Tg(Slc1a2-G-CaMP7) mice were obtained from RIKEN Brain Science Institute51. The number of mice assigned to different experimental groups was based on our experience, type of technical difficulties and previously published studies. All mice were housed under standard laboratory conditions with ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources (UCAR), University of Rochester Medical Center, or the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and followed standards of the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). Mice were allocated to different experimental groups randomly, and experiments were performed in a blinded manner where possible (such as during behaviour tests).

TBI

Hit-and-run moderate to severe closed-skull TBI was induced in lightly anaesthetized (3–5% isoflurane for 30–60 s) mice using a cortical impact device (Pittsburgh Precision Instruments)8,52. The device was modified/angled such that the metal rod was positioned horizontally to better serve the hit-and-run injury purpose. A polished stainless-steel tip (3 mm diameter) struck the mouse head with a speed of 5.2 mm s−1 and 0.1 s of contact time. The mouse (mildly anaesthetized) was hung head up vertically from its incisors by a metal ring. The impactor was positioned perpendicular to the skull at the loading point between the ipsilateral eye and midline on the horizontal side and the eye with bregma on the vertical side. After the impact, the animal fell onto a soft pad underneath. The above-described hit-and-run model was adopted from a previous study52 and can be configured to induce mild, moderate or severe injury. This study is based on the moderate injury paradigm due to the focus on TBI-induced cerebral oedema. TBI is variable in the clinic and so is the outcome of the hit-and-run TBI model, thus replicating real-life occurrences53–55. We overcome the variability by including a fairly large number of mice in each group.

After TBI, the mice were injected i.p. with saline or a cocktail of noradrenergic receptor inhibitors/antagonists (PPA): prazosin hydrochloride (10 μg per gram, P7791, Sigma-Aldrich), propranolol hydrochloride (10 μg per gram, P8688, Sigma-Aldrich), and atipamezole (1 μg per gram, A9611, Sigma-Aldrich) followed by two subsequent doses with a 24 h interval. The non-injury control groups received a sham hit and saline injection (i.p.).

Brain oedema measurement

Groups of mice were killed by decapitation at different timepoints after injury (10 min, 20 min, 30 min, 1 h and 3 h) and the brains were quickly removed. The olfactory bulb and cerebellum were discarded while the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres were placed on preweighed slides to determine the wet weight and were then dried in an oven at 85 °C for 48–72 h. The dry weight was measured on the same digital balance and the two weights were used to calculate the fractional water content of tissue per gram of dry weight.

Behaviour tests

Mice were assessed with a battery of behaviour tests, including neurological severity score, rota rod, wire grip, open field, novel object and Morris water maze (further details of the methodology are provided in the Supplementary Information). Testing was performed 2 and 12 weeks after injury.

IVIS spectrum infrared imaging

Mice were implanted with an intrastriatal cannula as described above21,23, subjected to TBI or a sham hit, treated with PPA or saline i.p. injection, and maintained under anaesthesia (1.5–2% isoflurane, administered through nose cones fitting within the imaging apparatus), and the infrared signals were recorded/imaged (excitation/emission; 640/690 nm) through the intact skull and femoral region using the IVIS Spectrum IR imager (PerkinElmer). The units for radiant efficiency were as follows: p s−1 cm−2 S−1 (μW cm−2)−1; p, photons, S, surface area.

Blood plasma collection for NA estimation.

Mice exposed to TBI were either injected with saline or PPA immediately after injury, and blood samples were withdrawn within 10 min after injury, taking into account the time needed for blood withdrawal in a fairly big cohort of mice and maintaining temporal consistency. In brief, a 25 G needle was inserted into the hearts of mildly anaesthetized (2.5–3% isoflurane) mice, and 0.5–0.8 ml blood was withdrawn. The syringe was emptied into a heparinized vial (1.5 ml, Eppendorf) before the plasma was separated by centrifugation (1,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and frozen at −80 °C for further processing.

Cerebral microdialysis and analysis of extracellular concentration of NA.

A dialysis guide cannula was positioned at the prefrontal cortex. The coordinates were anteroposterior (AP) +2.1 mm and mediolateral (ML) +0.3 mm from bregma and dorsoventral (DV) −0.7 mm from dura. The guide cannula was secured to the skull with dental cement. After implantation, the mice were allowed to recover for 2–3 days as described previously14. On the day of recording, TBI was induced and sampling of extracellular fluid was started immediately by infusion of filtered artificial CSF (155 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 2 mM Na2HPO4 and 0.85 mM MgCl2, adjusted to pH 7.30–7.35) at a rate of 1 μl min−1. Dialysates (30 μl, twice an hour) were collected in 0.5 ml Eppendorf tubes (placed on ice) from freely moving animals in their home cage, with or without TBI and PPA treatment up to 12 h after injury.

Concentrations of NA were determined in 10 μl samples by HPLC with electrochemical detection according to our established protocol14,56. The stationary phase was a Prodigy C18 column (100 mm × 2 mm inner diameter, 3 μm particle size, YMC Europe). The mobile phase consisted of 55 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM octane sulfonic acid, 0.1 mM Na2EDTA and 7% acetonitrile, adjusted to pH 3.7 with 0.1 M acetic acid, and with degassing using an online degasser, with isocratic flow at 0.55 ml min−1. The electrochemical detection was accomplished using an amperometric detector (Antec Decade, Antec) with a glass carbon electrode set at +0.7 V, with an Ag+/AgCl reference electrode. The output was recorded using the CSW system (Data Apex), which was used to calculate the electrochemical peak areas.

Influx of radiolabelled 22Na.

The influx of radionuclide was estimated as described previously14. In brief, the radionuclide 22Na (NaCl, Perkin Elmer) diluted either in artificial CSF or normal saline (final radioactivity concentration 0.1 μCi μl−1) was infused (10 μl, 2 μl min−1) through the cisterna magna in precanulated mice. For i.v. injection, PE10 tubing was inserted surgically into the femoral artery and the 22Na was infused at the same rate as in the cisterna magna. Mice received TBI or a sham hit followed immediately by i.p. injection of saline or PPA, administered less than 2 min before the start of the 22Na infusion. The cerebral hemispheres were collected 30 min after the start of 22Na infusion and homogenized by Solvable (Perkin Elmer) overnight, followed by addition of scintillation cocktail (5 ml per vial). The radioactivity content (maximum beta energy 0.546 MeV (89.8%), annihilation photons 0.511 MeV (180%)) was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (LS6500 Multipurpose Scintillation Counter, Beckman)14. Data were background-subtracted and calculated as the percentage of the total 22Na dose administered and compared statistically across the groups using GraphPad Prism.

Cervical lymphatic vessel isolation and pressure myography.

Mice were anaesthetized and the superficial CLVs were exposed by retraction of the skin from the tip of the lower jaw toward the top of the thoracic cavity. Both pairs of vessels were removed and transferred to a Sylgard dissection dish with Krebs buffer containing albumin. After pinning and cleaning, a vessel was cannulated using two glass micropipettes, pressurized to 3 cm H2O (294 Pa) and further cleaned of remaining tissue to enable accurate diameter tracking. The cannulated vessel, with chamber and pipette holder assembly, was transferred to the stage of an inverted microscope and connected through polyethylene tubing to a two-channel microfluidic device (Elveflow OB1 MK3) for pressure control. The inner diameter was tracked at 30–60 fps from bright-field images of the vessel as described previously31. Pressures were transiently set to 10 cm H2O (981 Pa) immediately after set-up and the vessel was stretched axially to remove slack, which minimized longitudinal bowing and associated diameter-tracking artifacts. Spontaneous contractions typically began within 15–30 min of warm-up at a pressure of 2 or 3 cm H2O (196–294 Pa), and the vessel was allowed to stabilize at 37 °C for 30–60 min before beginning an experimental protocol. A suffusion line connected to a peristaltic pump exchanged the chamber contents with Krebs buffer at a rate of 0.5 ml min−1.

Assessment of basal contractile function and concentration–response of drugs.

Spontaneous contractions were recorded at equal input and output pressures to prevent a pressure gradient for forward flow through the vessel during the experiments. When pressure was set at 3 cm H2O (294 Pa), the contraction frequency averaged around 15 min−1, which was a much higher rate than recorded in vivo. When pressure was lowered to 1 or 0.5 cm H2O, the contraction frequency fell into a range (5–10 min−1) closer to that recorded in vivo, so all subsequent protocols were performed at a pressure of 1 or 0.5 cm H2O (49–98 Pa). After the contraction pattern stabilized, a concentration–response curve to NA was performed over the range 1 × 10−9 M to 3 × 10−5 M. During that time, the bath was stopped, and each concentration of NA was given in 2 min intervals in a cumulative manner. The total concentration–response curve was completed within 20 min to prevent changes in bath osmolality from evaporation. In a separate protocol to evaluate the effects of pharmacological blockade of NA, PPA (10 ng ml−1) was added to the Krebs perfusion solution for 20 min before and during assessment of the concentration–response curve to NA. For contraction wave experiments, the vessel was exposed to a single dose of NA (3 μM) in the absence or presence of 10 ng ml−1 PPA, and contraction waves were assessed for 2–5 min. At the end of every experiment, each vessel was perfused with Ca2+-free Krebs buffer containing 3 mM EGTA for 20 min, and the passive diameter was recorded at the pressure used in the protocol.

Contractile function parameters.

After an experiment, custom-written analysis programs (LabVIEW) were used to detect the peak end-diastolic diameter (EDD), end-systolic diameter (ESD) and contraction frequency (FREQ) on a contraction-by-contraction basis. These data were used to calculate parameters that characterize lymphatic vessel contractile function. Each of the parameters represents the average of the respective values from all of the recorded contractions at a given NE concentration during a 2 min period. From concentration–response protocols, the following parameters were calculated and graphed:

where and represent the average EDD and frequency during the baseline period before the addition of a drug to the bath. represents the maximum passive diameter obtained under Ca2+-free Krebs buffer.

Solutions and chemicals.

Krebs buffer contained 146.9 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 3 mM NaHCO3, 1.5 mM Na-HEPES and 5 mM d-glucose (pH 7.4). Krebs-BSA buffer was prepared with the addition of 0.5% bovine serum albumin. During cannulation, Krebs-BSA buffer was present both luminally and abluminally, but during the experiment the bath solution was continuously exchanged with Krebs solution without albumin. All chemicals and drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, with the exception of BSA (United States Biochemicals), MgSO4 and Na-HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Assessment of contraction wave speed and entrainment.

Bright-field videos of contractions were acquired for 1–2 min at video rates ranging from 30 to 60 fps Recorded videos were then stored for offline processing, analysis and quantification of the conduction speed. Videos of contractions were processed frame by frame to generate two-dimensional spatiotemporal maps representing the measurement of the outside diameter (encoded in 8-bit grayscale) over time (horizontal axis) at every position along the vessel (vertical axis), as described previously31. All video processing and two-dimensional analyses were performed using a set of custom-written Python-based programs.

High-speed two-photon microscopy.

Mice were operated on to expose lymphatic vessels in the neck region as described above and then imaged for the flow of particles (polystyrene microspheres, 1.0 μm, 580/605 nm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and FITC–dextran (2,000 kDa, Invitrogen) using a two-photon microscope (resonant scanner Bergamo scope, Thorlabs) with an imaging frequency of 29.9–58.6 Hz using one/two-way scans. GCaMP7 mice were injected with BSA647 (66 kDa, Invitrogen) to visualize CLVs; further image processing and contrast adjustment enabled us to identify the dark-particle efflux as cells and debris, with possible colocalization with GCaMP7 cells. Vital signs (ECG and respiration) were recorded synchronously (3 kHz, ThorSync software) with the acquisition. Images were processed and analysed using ImageJ and custom MATLAB scripts23,57.

Lymphatic vessel contraction measurements.

Measurements of the in vivo CLV contraction amplitude and frequency (Fig. 4b) were obtained by analysing imaging time series using ImageJ and custom MATLAB scripts. The vessel diameter (Fig. 3i) was measured in each frame at one location near the centre of a lymphangion and averaged per recording and per mouse.

Particle tracking velocimetry and volume flow rate estimate.

Time series of two-photon imaging were registered as described previously57,58, using the green (intraluminal dextran) channel. Contiguous intervals, manually selected to ensure the stability of the field of view and registration accuracy, were used for estimating the average flow speed and median vessel diameter. Spatially and temporally resolved velocities were obtained by automated particle tracking velocimetry as described previously57,58. Mean flow speeds were computed by time-averaging all velocity measurements (in 10-pixel bins), and flow speeds were then spatially averaged. We required at least 30 separate measurements in space to ensure a reliable estimate of the mean. We recorded up to three independent mean flow speed measurements per mouse, which were averaged; if more than three were obtained, we retained the three with the largest number of speed measurements throughout space. The median vessel diameter was measured (using a custom MATLAB code) for the same temporal segments used for speed measurements. Images were first averaged in groups of 30 (about 1 s) to reduce noise and accelerate analysis. Then, 3–5 transverse profiles were interpolated onto a tenfold finer grid and the vessel diameter was measured with subpixel accuracy by identifying locations where the pixel intensity dropped to 20% of the maximum value. Finally, the median in space and time was computed. The volume flow rate was estimated as the average flow speed multiplied by the approximate cross-sectional area of the vessel, , where is the median vessel diameter. The retrograde flow percentage was computed by identifying the fraction of each time series in which fluid was flowing in the direction opposite to the net transport, as reported previously59,60.

Cell and cellular debris efflux.

Two-photon image time series were analysed to estimate size distributions and volumetric efflux rates of cells and cellular debris, which appeared as dark objects in the intraluminal dextran (green) channel. For each image, a dynamic background image (average of the adjacent 15 frames in time) was added then a Gaussian blur was computed and subtracted to improve lighting uniformity. Each image was slightly smoothed by applying a 3 × 3 pixel moving average and a region of interest (ROI) was selected for analysis. The ROI was binarized using the MATLAB function imbinarize with an adaptive threshold and the particles inside the ROI were fit to ellipses using the MATLAB function regionprops. The particle volume was estimated as , where is the semimajor axis length, is the semiminor axis length, and we estimated . Average particle distributions per unit volume were estimated (based on the ROI size), then multiplied by the estimated volume flow rate.

Lumped parameter lymphatic vessel simulations.

Flow through cervical lymphatic vessels was simulated using a lumped parameter model based on previous studies61–63. A series of four lymphangions was simulated with a lymphangion length of 0.2 cm, minimum valve resistance of 0.0375 mm Hg min μl−1, maximum valve resistance of 12.5 mm Hg min μl−1, active tension ranging from 7.5 × 10−4 to 2.25 × 10−3 mm Hg cm, contraction frequency ranging from 0.5 to 10 min−1, inlet pressure 1.58 mm Hg, outlet pressure 1.73 mm Hg and external pressure of 1.50 mm Hg; all other parameters matched those reported previously61. We solved a system of algebraic constraint equations using MATLAB’s nonlinear equation solvers (fzero and fsolve), and we then integrated a system of ordinary differential equations in time using a fourth-order Runge–Kutta method. We modelled conditions of different contraction amplitude by varying the active tension from 7.5 × 10−4 to 2.25 × 10−3 mm Hg cm with the contraction frequency fixed at 10 min−1. We modelled conditions of variable contraction frequency by varying the frequency from 0.5 to 10 min−1 with the active tension fixed at 1.4 × 10−3 mm Hg cm. Presented results come from the fourth (final) lymphangion in the simulation.

Image averaging and analyses.

Images were acquired using the following microscopes: wide-field fluorescent/epifluorescent microscope (MVX 10, Olympus), M205 FA fluorescence stereomicroscope equipped with an Xcite 200DC light source and A12801–01 W-View GEMINI (Leica), Montage/slid scanning microscope (Olympus), FV 500 confocal microscope (IX81, Olympus), SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems), FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus) and two/multiphoton galvoresonance scanner (Thorlabs). Field of view, ROIs, resolution and other acquisition factors were standardized, and the fluorescence intensity was estimated using image processing plugins in ImageJ. Fluorescence stereomicroscopic images at relevant timepoints were co-registered according to the position of the bregma and lambda on each mouse, then averaged using a custom ImageJ macro35.

Statistical analysis.

Data (n = ≥4 mice per group, each with multiple ROIs or replicates where applicable) were analysed for mean and standard error and depicted as bar graphs, box plots or line graphs. Specific statistical tests used for each figure are presented in the corresponding figure legends. Numerical values (used as mean per mouse in the analysis in case of repeated measures) were compared using Student’s -tests (unpaired, two-tailed), correlation matrix, regression analysis, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s test, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison test or non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test using Prism GraphPad software with 95% confidence interval.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text figures and/or extended data figures. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The particle tracking and vessel diameter measurement codes used in this study are publicly available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8165799). Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism Software (v.7). The LabVIEW program used for pressure and diameter data collection of isolated lymphatic vessels is publicly available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8286107). The LabVIEW program used for pressure and diameter data collection of isolated lymphatic vessels is publicly available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8286119). The Python program used for spatiotemporal analysis of contraction waves in isolated lymphatic vessels is publicly available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8259778).

Extended Data

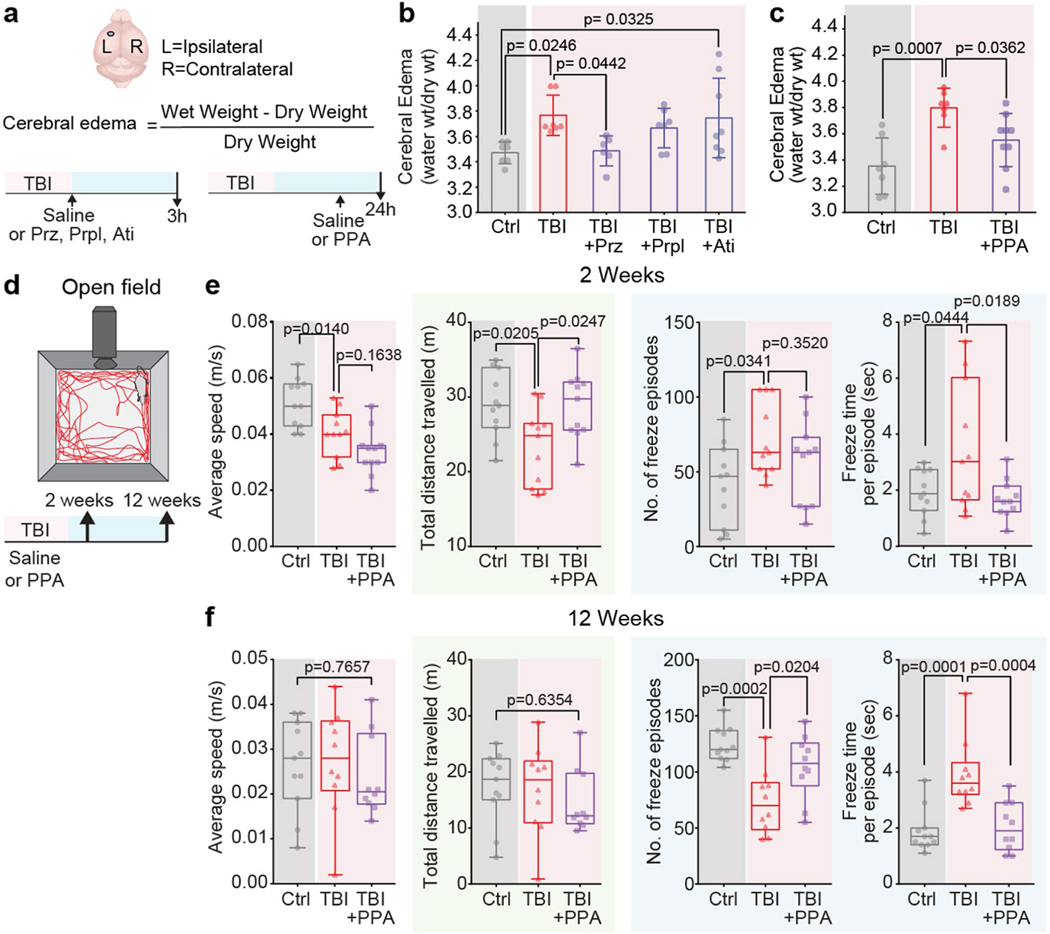

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Effect of individual components of PPA is less efficient in reducing cerebral oedema after TBI. Locomotor and anxiety-like behaviour of post-traumatic brain injury mice is relieved by PPA treatment.

a-b, The severity of cerebral oedema in the mouse brain was estimated 3 h post-TBI with or without treatment of prazosin (Prz), propranolol (Prpl), and atipamezole (Ati). Experimental groups were compared by one-way ANOVA (n = 35 mice, F4,30 = 3.73, p = 0.014,) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; Sham-Control vs TBI-saline (n = 7 mice each, p = 0.025), TBI-saline vs Prz (n = 6 mice, p = 0.044), Prpl (n = 7 mice, p = 0.72), and Ati (n = 8 mice, p = 0.99). c, Cerebral oedema measurement in mice 24 h post-TBI with or without PPA treatment at 23 h. Experimental groups compared by one-way ANOVA (n = 23 mice, F2,20 = 9.387, p = 0.001) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; Sham-Control (n = 7 mice) vs TBI-saline (n = 7 mice), p = 0.0007, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA (n = 9 mice, p = 0.036). d, Locomotion, anxiety-like behaviours, and exploration abilities at two and 12 weeks post-TBI, with or without PPA treatment. Data shown as box and whisker plot with median, and min-max values, the dots are biological replicates/mice. e, Two-week evaluation (n = 33 mice, 11 mice/group, group means were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test); average speed (F2,30 = 12.16, p = 0.0001; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.014, TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.164), total distance travelled (F2,30 = 5.291, p = 0.0108; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.021, TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.025), number of freeze episodes (F2,30 = 3.482, p = 0.0437; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.034; TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.352), and freeze time per episode (F2,30 = 4.944, p = 0.0139; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.044; TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.019). f, Twelve-week evaluation; n = 31 mice; Control (n = 11 mice), TBI-saline (n = 10 mice), TBI + PPA (n = 10 mice), group means were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable. Average speed (F2,28 = 0.2695, p = 0.7657), total distance travelled (F2,28 = 0.4609, p = 0.6354), number of freeze episodes (F2,28 = 11.47, p = 0.0002; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0002; TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.0204), and freeze time per episode (F2,28 = 14.2, p < 0.0001; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0001; TBI-saline vs TBI-PPA, p = 0.0004). Bar graphs show mean and SEM (b, c), box and whisker plots show median and min-max values (e, f), and the dots are biological replicates/mice.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Transcranial live imaging of tracer movement is as reliable as ex vivo and in vitro slice imaging.

a, Representative dorsal and ventral views of brain imaged by ex vivo conventional fluorescent microscopy in control, TBI+saline, and TBI + PPA groups performed at (top) day 0 and (bottom) six months post-TBI (n = 4 biological replicates/mice at each time point). b, Regression analysis of BSA-647 fluorescence intensity for quantifying association of (top) transcranial in vivo vs ex vivo dorsal and (bottom) transcranial in vivo vs in vitro slices (R2 = 0.802 and 0.821, respectively). c, Representative images from confocal microscopy showing vascular ultrastructure, labelled with lectin (red) and BSA-647 tracer (cyan), colocalized/distributed along the blood vessels in non-injury control, TBI-saline, and TBI + PPA groups. d, Experimental scheme. e, Representative images (n = 3 biological replicates/mice). f, Quantification of transcranial time-lapse imaging of Alexa flour 647 conjugated BSA tracer signals in vivo (n = 16 mice; Control (n = 5), TBI-saline (n = 4), TBI + PPA (n = 7), 60 time points, linear regression, F2,177 = 1144, p < 0.0001). g, Mean pixel intensity of BSA-647 in different regions of the brain (n = 5 mice/group, multiple slices averaged per mouse, group means compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable): dorsal cortex (F2,12 = 17.59, p = 0.0003; Control vs TBI-saline, P = 0.0002; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0098), striatum (F2,12 = 1.621, p = 0.238), hippocampus (F2,12 = 4.413, p = 0.0366; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0292; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.332), lateral cortex (F2,12 = 8.807, p = 0.0044; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0038; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0423), corpus callosum (F2,12 = 1.737, p = 0.217), and hypothalamus (F2,12 = 11.33, p = 0.0017; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0018; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.587). Data shown as scatter plot with trendline (b), line graph of group means with SEM (f), bars show mean and SEM (g), and the dots are biological replicates/mice. Scale: (a, c) 5 mm, (e) 100 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Post-TBI noradrenergic receptor inhibition downregulates IL-4, IL-6, TNF, and CXCL10 levels within the brain.

Brain samples collected 24 h post-TBI with or without PPA treatment were analysed for cytokine/chemokine levels both in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. Data is shown as percentage increase in the chemokine/cytokine levels relative to the contralateral hemisphere. Experimental groups were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. b, G-CSF (n = 27 mice; Control (n = 8), TBI-saline (n = 9), TBI + PPA (n = 10), F2,24 = 2.583, p = 0.0964). c, GM-CSF (n = 23 mice; Control (n = 7), TBI-saline (n = 7), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,20 = 1.021, p = 0.3781). d, IL-1 (n = 19 mice; Control (n = 7), TBI-saline (n = 7), TBI + PPA (n = 5), F2,16 = 4.427, p = 0.0295; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.038, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.083). e, IL-4 (n = 21 mice; 7 mice/group, F2,18 = 7.615, p = 0.0040; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.023, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0045). f, IL-6 (n = 24 mice; 8 mice/group, F2,21 = 4.653, p = 0.0212; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.032, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.049). g, IL-12p70 (n = 24 mice; Control (n = 9), TBI-saline (n = 8), TBI + PPA (n = 7), F2,21 = 4.739, p = 0.020; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.023, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0695). h, CXCL10 (n = 28 mice; Control (n = 11), TBI-saline (n = 8), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,25 = 6.384, p = 0.0058; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.013, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.010). i, KC (n = 30 mice; Control (n = 11), TBI-saline (n = 9), TBI + PPA (n = 10), F2,27 = 3.239, p = 0.0549; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0495, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.019). j, LIF (n = 20 mice; Control (n = 5), TBI-saline (n = 7), TBI + PPA (n = 8), F2,17 = 1.55, p = 0.241). k, MCP1 (n = 22 mice; Control (n = 8), TBI-saline (n = 6), TBI + PPA (n = 8), F2,19 = 6.328, p = 0.0078; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.006, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.098). l, MIG (n = 27 mice; 9 mice/group, F2,24 = 1.128, p = 0.341). m, MIP2 (n = 30 mice; Control (n = 10), TBI-saline (n = 9), TBI + PPA (n = 11), F2,27 = 3.735, p = 0.0370; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.029, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.39). n, RANTES (n = 28 mice; Control (n = 9), TBI-saline (n = 9), TBI + PPA (n = 10), F2,25 = 1.056, p = 0.3629). o, VEGF (n = 26 mice; Control (n = 9), TBI-saline (n = 8), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,23 = 7.53, p = 0.0031; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.010, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0048). p, INF- (n = 25 mice; Control (n = 9), TBI-saline (n = 7), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,22 = 1.077, p = 0.358). q, TNF (n = 24 mice; Control (n = 8), TBI-saline (n = 7), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,21 = 3.908, p = 0.0361; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.128, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.033). Data shown as bar charts of mean and SEM, and the dots are biological replicates/mice.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Post-TBI noradrenergic receptor inhibition reduces astrocytic hypertrophy, microglial invasion, and subsequent hyper-phosphorylation of tau.

a, Schematic showing induction of injury followed by a two-week experimental window. b, Coronal sections of mouse brain showing the lesion centre were immunostained for GFAP (red) and DAPI (blue); the site of injury/damaged somatosensory cortex, enlarged ventricles both on ipsilateral and contralateral sides, and the white matter tract corpus callosum are indicated by yellow arrows, white # symbols, and a white * sign, respectively, in non-injury control, TBI, and TBI + PPA slices. c, Brain sections (bregma; AP −0.8 to 2 mm) were immunostained for microglia (Iba-1, red) and pan-nuclear marker (DAPI, blue); the bottom right corner shows the region of interest. d, Quantification of immunofluorescence of GFAP (n = 18 mice, 6 mice/group, multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA, F2,15 = 11.6, p = 0.0009, Tukey’s multiple comparison test; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0007, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.033), number of microglia (n = 12 mice, 4 mice/group, multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA, F2,9 = 2.879, p = 0.108) and Iba-1 immunostaining (n = 16 mice; Control (n = 4), TBI-saline (n = 6), TBI + PPA (n = 6), multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA, F2,13 = 14.89, p = 0.0004, Tukey’s multiple comparison test; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0022; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0008). e, (Top) Schematic showing the experimental time window of western blot and immunohistochemistry experiments for detection of hyper-phosphorylation of tau protein. (Bottom) Western blot analysis was performed in whole brain homogenates for tau targets: pTauSer404, pTauThr205, and pTauSer262 (n = 3 biological replicates/mice). f, Representative images showing hyper-phosphorylation of tau at site Ser262, Tau5, and DAPI in separate sets of mice at six months after TBI, with or without NA pan-adrenergic receptor blockade. g-j, Quantification of immunostaining of pTau in the cortex, striatum, and hippocampus for targets. g, pTauSer262 (n = 13 mice; Control (n = 3), TBI-saline (n = 5), TBI + PPA (n = 5), multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable), Cortex: F2,10 = 5.122, p = 0.0294; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.029, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.133, Striatum: F2,10 = 13.7, p = 0.0014; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0010, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.085, Hippocampus: F2,10 = 15.92, p = 0.0008; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0007, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.011. h, pTauT212 (n = 15 mice, 5 mice per group, multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable), Cortex: F2,12 = 75.42, p < 0.0001; Control vs TBI-saline, p < 0.0001, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.001, Striatum: F2,12 = 22.89, p < 0.0001; Control vs TBI-saline, p < 0.0001, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.079, Hippocampus: n = 11 mice, Control (n = 5), TBI-saline (n = 3), TBI + PPA (n = 3), multiple slices averaged per mouse, F2,8 = 8.088, p = 0.0120; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0099, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.215. i, pTauThr205 (n = 15 mice, 5 mice per group, multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable), Cortex: F2,12 = 62.05, p < 0.0001; Control vs TBI-saline, p < 0.0001, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0034, Striatum: F2,12 = 14.37, p = 0.0007; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0005, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.076, Hippocampus: n = 11 mice, Control (n = 5), TBI-saline (n = 3), TBI + PPA (n = 3), multiple slices averaged per mouse, F2,8 = 12.94, p = 0.0031; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.0026, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.022. j, Tau5 (n = 11 mice, Control (n = 3), TBI-saline (n = 5), TBI + PPA (n = 3), multiple slices averaged per mouse, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test where applicable), Cortex: F2,8 = 6.605, p = 0.020; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.019, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.915, Striatum: F2,8 = 3.39, p = 0.086; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.073, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.571, Hippocampus: F2,8 = 5.412, p = 0.0326; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.029, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.24. Data shown as bar charts of mean and SEM, bars show mean and SEM, and the dots are biological replicates/mice. Scale: (b) 250 μm, (c) 50 μm, (f) 25 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Western blots of programmed cell death pathway proteins Caspase 7, 3, and 9 at two weeks post-injury, with or without PPA treatment. Despite the anticipated disruption of BBB, TBI does not increase the influx of mannitol, a BBB impermeable tracer.

a-b, Brain tissue was collected from control and TBI mice with or without PPA, homogenized in RIPA buffer, and analysed for the levels of programmed cell death markers Caspase 7, 3, and 9 (n = 2 biological replicates/mice). a, Schematics showing the tissue collection from ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, which was homogenized, followed by protein separation by gel electrophoresis and PVC membrane transfers. b, Caspase enzymes (7, 3, 9) were detected on PVC membrane by specific primary antibodies followed by LiCOR secondary antibody incubation and imaging using Odyssey Imager. c, Schematic illustrating the vascular compartment of the brain and intravenous injection (10 μL) of radiolabelled mannitol (14C). The radiotracer 14C labelled Mannitol was injected through an intra-arterial catheter immediately after TBI, and brain samples were collected 30 min later, weighed, and dissolved overnight. Their radioactivity was then measured using a liquid scintillation counter. d, Radioactivity data (n = 21 mice; Control (n = 6), TBI-saline (n = 6), TBI + PPA (n = 9)) is shown as percentage of the total injected dose in the vasculature. Group means were compared by one-way ANOVA (F2,18 = 8.13, p = 0.003) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test; Control vs TBI-saline, p = 0.025; TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.0027; Control vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.73. Data shown as box and whisker plot with the lower and upper quartile (box limits), median and min-max values, and the dots represent biological replicates/mice.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Post-TBI noradrenergic inhibition restores interstitial fluid flow, tracer dispersion and efflux.

a, Schematic showing fluorescent tracer Direct Blue 53 (DB53) injected into the striatum in pre-cannulated mice, with or without TBI. DB53 was detected in vivo within the live brain 3 h post-TBI by IVIS Spectrum IR imaging. b, Averaged images showing the distribution of DB53 in the brain. c, IR quantification shown as radiant efficiency is compared using one-way ANOVA; n = 19 mice; Control (n = 6), TBI-saline (n = 6), TBI + PPA (n = 9), F2,16 = 23.5, p < 0.0.0001, Tukey’s multiple comparison test; Control vs TBI-saline, p < 0.0001, TBI-saline vs TBI + PPA, p = 0.005. d, Schematic diagram illustrating the methods used to assess the efflux of tracer from the brain into the circulatory system, thus quantifying fluid transport out of the brain and oedema clearance. DB53 was injected into the left striatum, and its appearance within a femoral vein was recorded using time-lapse IVIS spectrum IR imaging. e, Representative images showing the distribution of DB53 (640–690 nm) in the femoral vein: Control (top row), TBI-saline (middle row), and TBI + PPA groups (bottom row). f, DB53 IR signals from different experimental groups are quantified, and values shown as radiant efficiency (n = 15, 5 mice per group, two-way ANOVA, F2,156 = 242.1, p < 0.0001, Tukey’s multiple comparison test; Control vs. TBI-saline, p < 0.0001; TBI saline vs. TBI + PPA, p = 0.0002). Data shown as box and whisker plot with the lower and upper quartile (box limits), median and min-max values (c) or line graph with group means and continuous SEM (f); the dots are biological replicates/mice. Scale bars: 5 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. PPA administration in healthy mice results in enhanced clearance of radiotracers from CSF.