Resumo

Fundamento:

A introdução das antraciclinas no tratamento do câncer infantojuvenil propiciou um aumento significativo na sobrevida, mas também nas taxas de morbimortalidade devido às complicações cardiovasculares (CVs).

Objetivos:

Conhecer o perfil cardiológico de pacientes pediátricos tratados com antraciclinas em um centro oncológico no Brasil e a incidência das complicações CVs.

Métodos:

Foram coletados, de prontuários de pacientes de ambos os sexos com idade até 19 anos – frequência e forma de apresentação clínica das complicações CVs Gerais (G1) e relacionadas à Disfunção Ventricular (G2) – e correlacionados com fatores de risco, faixa etária e estado vital, medicações cardiológicas e cardioprotetoras. Um valor de p < 0,05 foi considerado significativo.

Resultados:

Foram incluídos 326 pacientes, destes, 214 (65,6%) eram menores de 10 anos e 192 (58,89%) do sexo masculino. As complicações do G1 ocorreram em 141 (43,3%) pacientes e a mais frequente foi a hipertensão arterial sistêmica; as complicações do G2 ocorreram em 84 pacientes (25,76%). Uma Dose Cumulativa (DC) das antraciclinas > 250mg/m2 foi usada em 26,7% dos pacientes e a associação de complicações do G2 com essa DC não mostrou significância estatística (p=0,305; RC=1,330 e [95% IC= 0,770- 2,296]). As medicações cardiológicas mais usadas foram os diuréticos em 34,7% dos pacientes.

Conclusões:

O estudo mostrou, como na literatura, uma alta incidência de complicações CVs no tratamento do câncer infantojuvenil, sendo as do G1 as mais frequentes.

Palavras-chave: Cardiotoxicidade, Antraciclinas, Neoplasias, Criança, Tratamento Farmacológico

Introdução

Nas últimas décadas, a taxa de sobrevida após o tratamento do câncer infantojuvenil aumentou consideravelmente, cerca de 80%, principalmente pela introdução de novos protocolos terapêuticos.1,2 Contudo, devido aos efeitos adversos sobre o sistema cardiovascular (CV), houve um aumento na morbimortalidade de 8,4 vezes em sobreviventes.2,3

As complicações CVs podem levar a, pelo menos, uma internação em até 8,1% dos casos após o tratamento,1 com taxa de hospitalização 14 vezes maior em sobreviventes na primeira década de vida, comparada com adultos de 60 anos.1Essas complicações podem ser causadas por diferentes grupos de quimioterápicos e ter diferentes formas de apresentação.1,2 As alterações relacionadas à disfunção cardíaca estão mais frequentemente ligadas à toxicidade das antraciclinas ao cardiomiócito e à microvasculatura.4,5 Ela é causada principalmente pelo estresse oxidativo, com a formação do complexo ferro-antraciclina intracelular responsável pela geração dos radicais superóxidos e pela ação sobre a enzima topoisomerase 2β, sinalizando a necrose e a apoptose celular.4 O dexrazoxano, é um quelante de ferro que inibe a formação desses complexos quando administrado antes de cada dose de antraciclina, minimizando os efeitos cardiotóxicos, e é empregado com função cardioprotetora.4–7

A presença de disfunções cardíacas associadas ao quadro de insuficiência cardíaca foi descrita, pela primeira vez, como um efeito adverso das antraciclinas, em 1967, e a relação com a dose, em 1971, podendo se manifestar logo após a exposição ou anos depois do tratamento.2,3,5,8,9 Os estudos com análise retrospectiva de efeitos tardios em sobreviventes de tratamento de câncer foram as principais fontes para o conhecimento atual sobre a cardiotoxicidade dessas medicações.8,9

No Brasil, embora haja vários centros pediátricos de tratamento oncológico, ainda carecemos de dados estatísticos mais robustos sobre a incidência de complicações CVs nesta população. O objetivo deste estudo é conhecer o perfil cardiológico de pacientes oncológicos pediátricos que usaram antraciclinas em um centro oncológico brasileiro, identificando a frequência dessas alterações, os fatores de risco, e as formas clínicas de apresentação, para que essas informações possam auxiliar na formulação de futuras estratégias de prevenção e redução de danos.

Métodos

Delineamento do estudo

Este foi um estudo observacional, longitudinal, retrospectivo, descritivo e analítico, realizado por meio de pesquisa em prontuários físicos e eletrônicos. Realizou-se coleta de dados desde o início do tratamento dos pacientes, com os seguintes critérios de inclusão: ambos os sexos, com idade até 19 anos, portadores de doença neoplásica tratados com antraciclinas, com início de tratamento entre 2014 e 2018 e conclusão até 10 de abril de 2020. Os critérios de exclusão foram informações incompletas.

Esta pesquisa foi desenvolvida após aprovação pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisas da nossa instituição conforme protocolo no 3.711.502.

Variáveis do estudo e coleta de dados

Foram consideradas as seguintes variáveis: idade ao diagnóstico; sexo; procedência; tipo de câncer e sua distribuição por faixa etária; complicações CV, uso de medicações cardiológicas e de dexrazoxano; relação das complicações CV com idade e estado vital (vivo/óbito); causas dos óbitos e avaliação cardiológica.

As complicações CVs foram divididas em dois grupos: Gerais (G1) e Disfunção Ventricular (G2). As complicações do G1 foram Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica (HAS); derrame pericárdico; Fenômenos Tromboembólicos (FTE) venosos; alterações do ritmo; miocardite; endocardite; isquemia ou Infarto Agudo do Miocárdio (IAM); acidente vascular cerebral (AVC) e insuficiência cardíaca congestiva (ICC) por causas não relacionadas às antraciclinas.4,5,10 As complicações G2 foram cardiotoxicidade suspeita, determinada pela queda da Fração de Ejeção do Ventrículo Esquerdo (FEVE) em 10 pontos em relação ao ecocardiograma basal e maior ou igual a 55%; disfunção diastólica de ventrículo direito (DD-VD); disfunção diastólica do ventrículo esquerdo (DD-VE); disfunção sistólica do VE (DS-VE) quando FEVE < 55% e percentual de encurtamento sistólico (%D < 28%).4,5 A % D e a FEVE foram avaliadas pelo ecocardiograma convencional, pelo modo M com método de Teichholz; e a função diastólica foi avaliada pelo Doppler pulsado e tecidual e pela análise do diâmetros do átrio esquerdo, por mais de um observador.

Os fatores de risco para cardiotoxicidade relacionados ao G2 avaliados foram idade; sexo feminino; Dose Cumulativa (DC) de antraciclinas maior que 250mg/m2; associação com outras drogas cardiotóxicas (ifosfamida e ciclofosfamida), radioterapia mediastinal ou torácica; presença de síndrome genética, e presença de cardiopatia congênita. A DC das antraciclinas foi convertida em doxorrubicina-equivalência.11

Análise estatística

Foram feitas análises descritivas e de associação. As variáveis qualitativas nominais e ordinais foram apresentadas por meio de frequência (n) e porcentagem (%). Foram avaliadas associações das complicações CVs relacionadas à faixa etária e ao estado vital; a média da idade ao diagnóstico foi descrita por média e desvio-padrão. As análises foram feitas por meio do teste qui-quadrado de Pearson com correção de continuidade (estado vital) e simulação de Monte Carlo (para faixa etária) quando necessário (ao menos uma célula tinha uma frequência esperada menor que 5). Para o estado vital, foi possível calcular a razão de chance para variáveis com duas categorias e na ausência de células iguais a zero. As análises dos dados foram realizadas no programa IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 23, de 2015. O nível de significância utilizado em todo o estudo foi de 5%.

Resultados

Dos 826 pacientes admitidos, 444 (53,7%) usaram antraciclinas e, desses, 326 (73,4%) foram incluídos. A procedência foi determinada em 302 (92,6%) pacientes, sendo 155 (47,5%) residentes no Distrito Federal; a média da idade ao diagnóstico foi de 6,8 anos com desvio-padrão de 5,0 anos e houve predomínio do sexo masculino com 192 (58,9 %). A Tabela 1 resume os tipos de câncer por faixa etária.

Tabela 1. Tipo de câncer em diferentes faixas etárias.

| Faixa etária ao diagnóstico | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 ano | 1 a 4 anos | 5 a 9 anos | 10 a 14 anos | 15 a 19 anos | ||||

| Tipo | Leucemias | n (%) | 9 (39,13) | 77 (63,64) | 36 (51,43) | 34 (39,08) | 11 (44,00) | 167 (51,23) |

| Linfomas | n (%) | 0 (00,00) | 9 (7,44) | 21 (30,00) | 18 (20,69) | 9 (36,00) | 57 (17,48) | |

| Tumor Renal | n (%) | 4 (17,39) | 16 (13,22) | 4 (5,71) | 0 (0,00) | 0 (0,00) | 24 (7,36) | |

| Neuroblastomas | n (%) | 8 (34,78) | 11 (9,09) | 1 (1,43) | 2 (2,30) | 0 (0,00) | 22 (6,75) | |

| Tumores hepáticos | n (%) | 0 (0,00) | 3 (2,48) | 2 (2,86) | 2 (2,30) | 0 (0,00) | 7 (2,15) | |

| Osteossarcomas | n (%) | 0 (0,00) | 1 (0,83) | 1 (1,43) | 15 (17,24) | 4 (16,00) | 21 (6,44) | |

| Sarcomas | n (%) | 2 (8,70) | 4 (3,31) | 5 (7,14) | 12 (13,79) | 1 (4,00) | 24 (7,36) | |

| Outros | n (%) | 0 (0,00) | 0 (0,00) | 0 (0,00) | 4 (4,60) | 0 (0,00) | 4 (1,23) | |

| Total | n | 23 | 121 | 70 | 87 | 25 | 326 | |

| % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

Complicações CV do G1

As complicações CVs do G1 ocorreram em 141 (43,3%) pacientes, sendo que em alguns houve mais de uma complicação. A HAS ocorreu em 50 (15,3%); derrame pericárdico em 48 (14,7%); FTE em 41 (12,57%); alteração do ritmo em 32 (9,8%); ICC com uso de drogas vasoativas em 25 (7,7%); miocardite em 4 (1,22%); endocardite em 4 (1,2%); isquemia com IAM em 1 (0,3%) e AVC em 1 (0,3%).

Complicações CV do G2 e associação com fatores de risco para cardiotoxicidade

As complicações CV do G2 ocorreram em 84 (25,8%) pacientes, sendo que em alguns houve mais de uma complicação. A suspeita da cardiotoxicidade ocorreu em 49 (15,0%); a DD-VD em 15 (4,6%); a DD-VE em 36 (11,0%); e a DS-VE em 24 (7,4%). Não se observou associação significativamente entre os fatores de risco para cardiotoxicidade e complicações do G2 (Tabela 2).

Tabela 2. Associação dos fatores de risco para cardiotoxicidade com complicações cardiovasculares do grupo G2 (disfunção ventricular).

| Complicação cardiovascular do G2 | Total n (%) |

p | RC | IC 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Não n (%) |

Sim n (%) |

||||||

| < 5 anos | Não | 128 (52,89) | 54 (64,29) | 182 (55,83) | 0,070 | 0,624 | 0,374 - 1,042 |

| Sim | 114 (47,11) | 30 (35,71) | 144 (44,17) | ||||

| Sexo feminino | Masculino | 141 (58,26) | 51 (60,71) | 192 (58,90) | 0,694 | 0,903 | 0,544 - 1,500 |

| Feminino | 101 (41,74) | 33 (39,29) | 134 (41,10) | ||||

| Síndrome Genética | Sim - S Down | 8 (3,31) | 1 (1,19) | 9 (2,76) | 0,561 | - | - |

| Sim - Outra | 11 (4,55) | 3 (3,57) | 14 (4,29) | ||||

| Não | 223 (92,15) | 80 (95,24) | 303 (92,94) | ||||

| Cardiopatia prévia | Sim | 11 (4,55) | 3 (3,57) | 14 (4,29) | 0,947 | 1,286 | 0,350 - 4,724 |

| Não | 231 (95,45) | 81 (96,43) | 312 (95,71) | ||||

| DC de antraciclinas | Dose até 249 | 181 (74,79) | 58 (69,05) | 239 (73,31) | 0,305 | 1,330 | 0,770 - 2,296 |

| Dose > 250 | 61 (25,21) | 26 (30,95) | 87 (26,69) | ||||

| Radioterapia | Sim | 19 (7,85) | 5 (5,95) | 24 (7,36) | 0,566 | 1,346 | 0,486 - 3,726 |

| Mediastinal/tórax | Não | 223 (92,15) | 79 (94,05) | 302 (92,64) | |||

| Outras Drogas cardiotóxicas | Sim | 147 (60,74) | 61 (72,62) | 208 (63,80) | 0,051 | 0,583 | 0,338 - 1,006 |

| Não | 95 (39,26) | 23 (27,38) | 118 (36,20) | ||||

| TOTAL | 242 (100) | 84 (100) | 326 (100) | ||||

DC: dose cumulativa; RC: risco de chance (Oddis ratio); IC: intervalo de confiança.

Uso de drogas cardiológicas e de Dexrazoxano

As drogas cardiológicas mais utilizadas foram: diuréticos por 113 (34,7%) pacientes, anti-hipertensivos por 56 (17,2%) e drogas vasoativas por 54 (16,6%).

Dos 73 pacientes que usaram Dexrazoxano, 18 (24,7%) apresentaram as complicações do G2, e somente 36 (49,3%) usaram o cardioprotetor em 100% das doses de antraciclinas. Dos 253 pacientes que não usaram, 66 (26,08%) apresentaram complicações do G2. O uso da Dexrazoxano não mostrou associação significante com cardioproteção (p=0,806; RC=1,078 e [95% I.C.= 0,591-1,968]).

Complicações CVs do G1 e G2 e associação com faixa etária e estado vital

As complicações CV dos G1 e G2 ocorreram em 173 (53,1%) pacientes. A Tabela 3 resume a associação dessas complicações e a faixa etária ao diagnóstico, e a Tabela 4, a associação entre as complicações do G1 e G2 com estado vital

Tabela 3. Análise de associação das complicações cardiovasculares gerais (G1) e disfunção ventricular (G2) com faixa etária ao diagnóstico.

| Faixa etária | Total | p* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 ano n (%) |

1-4 anos n (%) |

5-9 anos n (%) |

10-14 anos n (%) |

15-19anos n (%) |

||||

| Alterações do ritmo | Não | 21 (91,3) | 109 (90,1) | 65 (92,9) | 76 (87,4) | 23 (92,0) | 294 (90,2) | 0,839 |

| Sim | 2 (8,7) | 12 (9,9) | 5 (7,1) | 11 (12,6) | 2 (8,0) | 32 (9,8) | ||

| Miocardite | Não | 23 (100,0) | 119 (98,3) | 69 (98,6) | 87 (100,0) | 24 (96,0) | 322 (98,8) | 0,553 |

| Sim | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,7) | 1 (1,4) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (4,0) | 4 (1,2) | ||

| Isquemia- IAM | Não | 23 (100,0) | 121 (100,0) | 70 (100,0) | 87 (100,0) | 24 (96,0) | 325 (99,7) | 0,143 |

| Sim | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (4,0) | 1 (0,3) | ||

| HAS | Não | 15 (65,2) | 104 (85,9) | 58 (82,9) | 77 (88,5) | 22 (88,0) | 276 (84,7) | 0,080 |

| Sim | 8 (34,8) | 17 (14,1) | 12 (17,1) | 10 (11,5) | 3 (12,0) | 50 (15,3) | ||

| FTE com cateter | Não | 23 (100,0) | 118 (97,5) | 66 (94,3) | 83 (95,4) | 24 (96,0) | 314 (96,3) | 0,696 |

| Sim | 0 (0,00) | 3 (2,5) | 4 (5,7) | 4 (4,6) | 1 (4,0) | 12 (3,7) | ||

| FTE sem cateter | Não | 21 (91,3) | 113 (93,4) | 63 (90,0) | 79 (90,8) | 21 (84,0) | 297 (91,1) | 0,672 |

| Sim | 2 (8,7) | 8 (6,6) | 7 (10,0) | 8 (9,2) | 4 (16,0) | 29 (8,9) | ||

| DP sem antraciclinas | Não | 22 (95,6) | 113 (93,4) | 64 (91,4) | 82 (94,3) | 20 (80,0) | 301 (92,3) | 0,163 |

| Sim | 1 (4,4) | 8 (6,6) | 6 (8,6) | 5 (5,7) | 5 (20,0) | 25 (7,7) | ||

| DP com antraciclinas | Não | 22 (95,6) | 112 (92,6) | 69 (98,6) | 81 (93,1) | 23 (92,0) | 307 (94,2) | 0,481 |

| Sim | 1 (4,4) | 9 (7,4) | 1 (1,4) | 6 (6,9) | 2 (8,0) | 19 (5,8) | ||

| DP com drenagem | Não | 22 (95,6) | 121 (100,0) | 70 (100,0) | 84 (96,5) | 25 (100,0) | 322 (98,8) | 0,073 |

| Sim | 1 (4,4) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 3 (3,5) | 0 (0,0) | 4 (1,2) | ||

| AVC | Não | 22 (95,6) | 121 (100,0) | 70 (100,0) | 87 (100,0) | 25 (100,0) | 325 (99,7) | 0,069 |

| Sim | 1 (4,5) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 0 (0,0) | 1 (0,3) | ||

| ICC com DVA | Não | 17 (73,9) | 113 (93,4) | 66 (94,3) | 82 (94,3) | 23 (92,0) | 301 (92,3) | 0,019 |

| Sim | 6 (26,1) | 8 (6,6) | 4 (5,7) | 5 (5,7) | 2 (8,0) | 25 (7,7) | ||

| Endocardite | Não | 22 (95,6) | 120 (99,2) | 69 (98,6) | 86 (98,8) | 25 (100,0) | 322 (98,8) | 0,740 |

| Sim | 1 (4,4) | 1 (0,8) | 1 (1,4) | 1 (1,2) | 0 (0,0) | 4 (1,2) | ||

| DD-VD | Não | 22 (95,6) | 117 (96,7) | 68 (97,1) | 81 (93,1) | 23 (92,0) | 311 (95,4) | 0,622 |

| Sim | 1 (4,4) | 4 (3,3) | 2 (2,9) | 6 (6,9) | 2 (8,0) | 15 (4,6) | ||

| Cardiotoxicidade suspeita | Não | 19 (82,6) | 108 (89,3) | 56 (80,0) | 74 (85,1) | 20 (80,0) | 277 (85,0) | 0,458 |

| Sim | 4 (17,4) | 13 (10,7) | 14 (20,0) | 13 (14,9) | 5 (20,0) | 49 (15,0) | ||

| DD-VE | Não | 20 (87,0) | 110 (90,9) | 63 (90,0) | 74 (85,1) | 23 (92,0) | 290 (89,0) | |

| Sim DC=0 | 1 (4,3) | 3 (2,5) | 0 (0,0) | 6 (6,9) | 1 (4,0) | 11 (3,4) | 0,766 | |

| Sim DC<250 | 2 (8,7) | 6 (5,0) | 6 (8,6) | 6 (6,9) | 1 (4,0) | 21 (6,4) | ||

| Sim DC>250 | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,6) | 1 (1,4) | 1 (1,1) | 0 (0,0) | 4 (1,2) | ||

| DS-VE | Não | 23 (100,0) | 118 (97,5) | 63 (90,0) | 78 (89,6) | 20 (80,0) | 302 (92,7) | |

| Sim DC=0 | 0 (00,0) | 0 (00,00) | 0 (00,0) | 4 (4,6) | 0 (00,0) | 4 (1,2) | 0,009 | |

| Sim DC<250 | 0 (00,0) | 1 (0,8) | 6 (8,6) | 4 (4,6) | 3 (12,0) | 14 (4,3) | ||

| Sim DC>250 | 0 (0,0) | 2 (1,7) | 1 (1,4) | 1 (1,2) | 2 (8,0) | 6 (1,8) | ||

| TOTAL | 23 (100) | 121 (100) | 70 (100) | 87 (100) | 25 (100) | 326 (100) | ||

IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; FTE: fenômenos tromboembólicos; DP: derrame pericárdico; AVC: acidente vascular cerebral; ICC com DVA: insuficiência cardíaca com uso de drogas vasoativas; DD-VD: disfunção diastólica de ventrículo direito; DD-VE: disfunção diastólica de ventrículo esquerdo; DS-VE: disfunção sistólica de ventrículo esquerdo, DC: dose cumulativa;

Nível de significância de 5%.

Tabela 4. Análise de associação das complicações cardiovasculares gerais (G1) e disfunção ventricular (G2) com estado vital.

| Estado Vital | Óbito n (%) | p* | RC | IC 95% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (%) | Vivo n (%) | ||||||

| Alterações do ritmo | Não | 210 (89,36) | 84 (92,31) | 294 (90,18) | 0,423 | 0,700 | 0,292 - 1,680 |

| Sim | 25 (10,64) | 7 (7,69) | 32 (9,82) | ||||

| Miocardite | Não | 234 (99,57) | 88 (96,70) | 322 (98,77) | 0,121 | 7,977 | 0,819 - 77,711 |

| Sim | 1 (0,43) | 3 (3,30) | 4 (1,23) | ||||

| Isquemia- IAM | Não | 235 (100,00) | 90 (98,90) | 325 (99,69) | 0,622 | - | - |

| Sim | 0 (0,00) | 1 (1,10) | 1 (0,31) | ||||

| HAS | Não | 210 (89,36) | 66 (72,53) | 276 (84,66) | <0,001 | 3,182 | 1,712 - 5,912 |

| Sim | 25 (10,64) | 25 (27,47) | 50 (15,34) | ||||

| FTE com cateter | Não | 227 (96,60) | 87 (95,60) | 314 (96,32) | 0,921 | 1,305 | 0,383 - 4,443 |

| Sim | 8 (3,40) | 4 (4,40) | 12 (3,68) | ||||

| FTE sem cateter | Não | 216 (91,91) | 81 (89,01) | 297 (91,10) | 0,409 | 1,404 | 0,626 - 3,146 |

| Sim | 19 (8,09) | 10 (10,99) | 29 (8,90) | ||||

| DP sem antraciclinas |

Não | 220 (93,62) | 81 (89,01) | 301 (92,33) | 0,161 | 1,811 | 0,782 - 4,193 |

| Sim | 15 (6,38) | 10 (10,99) | 25 (7,67) | ||||

| DP com antraciclinas | Não | 226 (96,17) | 81 (89,01) | 307 (94,17) | 0,013 | 3,100 | 1,216 - 7,902 |

| Sim | 9 (3,83) | 10 (10,99) | 19 (5,83) | ||||

| DP com drenagem | Não | 234 (99,57) | 88 (96,70) | 322 (98,77) | 0,121 | 7,977 | 0,819 - 77,711 |

| Sim | 1 (0,43) | 3 (3,30) | 4 (1,23) | ||||

| AVC | Não | 234 (99,57) | 91 (100,00) | 325 (99,69) | 1,000 | - | - |

| Sim | 1 (0,43) | 0 (0,00) | 1 (0,31) | ||||

| ICC com DVA | Não | 225 (95,74) | 76 (83,52) | 301 (92,33) | <0,001 | 4,441 | 1,915 - 10,300 |

| Sim | 10 (4,26) | 15 (16,48) | 25 (7,67) | ||||

| Endocardite | Não | 232 (98,72) | 90 (98,90) | 322 (98,77) | 1,000 | 0,859 | 0,088 - 8,369 |

| Sim | 3 (1,28) | 1 (1,10) | 4 (1,23) | ||||

| DD-VD | Não | 227 (96,60) | 84 (92,31) | 311 (95,40) | 0,173 | 2,365 | 0,832 - 6,722 |

| Sim | 8 (3,40) | 7 (7,69) | 15 (4,60) | ||||

| Cardiotoxicidade subclínica | Não | 195 (82,98) | 82 (90,11) | 277 (84,97) | 0,106 | 0,535 | 0,248 - 1,153 |

| Sim | 40 (17,02) | 9 (9,89) | 49 (15,03) | ||||

| DD-VE | Não | 211 (89,79) | 79 (86,81) | 290 (88,96) | 0,676 | - | - |

| Sim DC=0 | 6 (2,55) | 5 (5,49) | 11 (3,37) | ||||

| Sim DC<250 | 15 (6,38) | 6 (6,59) | 21 (6,44) | ||||

| Sim DC>250 | 3 (1,28) | 1 (1,10) | 4 (1,23) | ||||

| DS-VE | Não | 219 (93,19) | 83 (91,21) | 302 (92,64) | 0,757 | - | - |

| Sim DC=0 | 3 (1,28) | 1 (1,10) | 4 (1,23) | ||||

| Sim DC<250 | 10 (4,26) | 4 (4,40) | 14 (4,29) | ||||

| Sim DC>250 | 3 (1,28) | 3 (3,30) | 6 (1,84) | ||||

| TOTAL | 235 (100) | 91 (100) | 326 (100) | ||||

IAM: infarto agudo do miocárdio; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; FTE: fenômenos tromboembólicos; DP: derrame pericárdico; AVC: acidente vascular cerebral; ICC com DVA: insuficiência cardíaca com uso de drogas vasoativas; DD-VD: disfunção diastólica de ventrículo direito; DD-VE: disfunção diastólica de ventrículo esquerdo; DS-VE: disfunção sistólica de ventrículo esquerdo; DC: dose cumulativa;

Nível de significância de 5%.

Causas de óbitos

Foram a óbito 91 (27,91%) pacientes. O tempo médio até o óbito foi 17 meses, as causas foram recorrência e/ou progressão da doença em 57 (62,6%) pacientes, doenças infecciosas e/ou parasitárias em 16 (17,6%), insuficiência respiratória aguda em oito (8,8%), doença CV em cinco (5,5%), e outras em cinco (5,5%).

Avaliação cardiológica

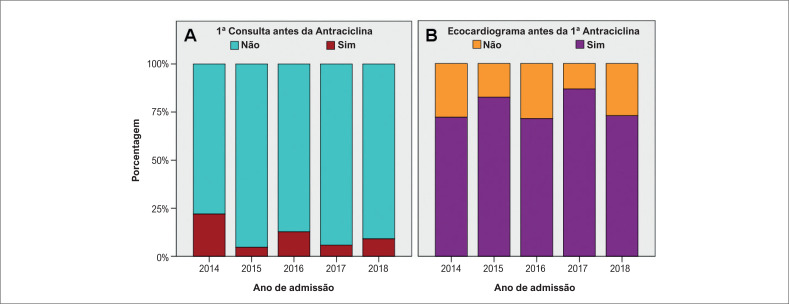

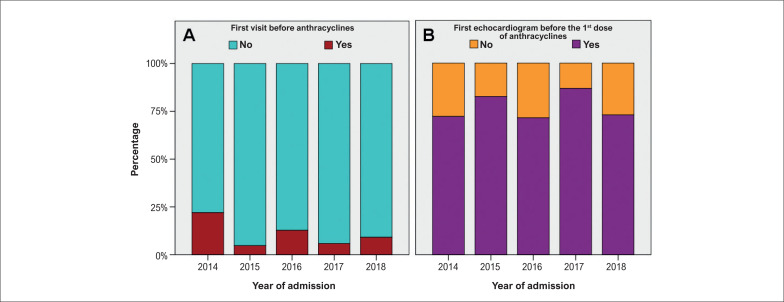

Realizaram consulta cardiológica pediátrica 216 pacientes (66.3%) e 318 ecocardiograma (97,54%). A Figura 1A e B resume a porcentagem de pacientes que compareceram na primeira consulta e que realizaram o ecocardiograma antes da primeira dose de antraciclinas.

Figura 1. A) Primeira consulta x primeira dose de antraciclinas. B) Primeiro ecocardiograma x primeira dose de antraciclinas.

Discussão

As antraciclinas são empregadas em mais de 50% dos tratamentos de câncer infantojuvenil.12

Segundo o Ministério da Saúde, existem 317 unidades habilitadas para o tratamento de câncer no Brasil;13 mesmo assim, aproximadamente 50% dos pacientes do estudo não residiam no Distrito Federal.

Em concordância com a literatura, houve predominância em crianças de até quatro anos de idade e do sexo masculino (Tabela 1).14–16 Além disso, predominaram as leucemias (Tabela 1) que correspondem a 33% de todos os cânceres na faixa etária entre 0 e 14 anos.17,18

Durante e após o tratamento, diversas complicações CV podem ocorrer, com diferentes formas de apresentação clínica e gravidade3,10,19(Tabelas 3 e 4), podendo ocorrer antes do uso das antraciclinas nas leucemias.20,21

Segundo a literatura, durante o tratamento do câncer infantojuvenil, as alterações CVs são as complicações mais frequentes não relacionadas ao tumor, que podem contribuir para uma maior morbimortalidade precoce na vida adulta. Apesar disso, não dispomos de dados estatísticos robustos da incidência dessas complicações nessa população em território brasileiro, podendo dar/ a impressão de que essas alterações não estão presentes em nossa realidade. A pesquisa constatou, como descrito na literatura, que as complicações CVs foram frequentes, mas, para nossa surpresa, as mais prevalentes foram as não relacionadas à disfunção ventricular. Assim, essas formas de apresentação devem ser consideradas na formulação das estratégias de prevenção.

As Tabelas 3 e 4 resumem a frequência das complicações CVs, sendo a HAS a mais prevalente, provavelmente relacionada ao emprego de glicocorticoides na fase de indução de alguns protocolos, e isso pode explicar por que as drogas mais usadas foram os diuréticos e anti-hipertensivos.22 O derrame pericárdico pode ocorrer em até 21% dos pacientes;4 no estudo, essa foi a segunda complicação CV mais comum, ocorrendo mesmo antes do uso das antraciclinas. Os FTE venosos corresponderam à terceira complicação CV mais frequente, podendo ocorrer pela presença de acesso venoso de longa permanência ou pelo efeito trombogênico das células tumorais, com incidência de até 20% em pacientes adultos hospitalizados e 8% nas crianças.3–5 A incidência das alterações do ritmo cardíaco pode estar subestimada devido a não realização de método diagnóstico de rotina; a incidência descrita é de até 38%.4 A ICC por outras causas, com uso de drogas vasoativas, ocupou o quinto lugar no estudo, e isso pode ocorrer devido à sobrecarga volêmica, imunossupressão que favorece quadros infecciosos com disfunção miocárdica transitória e/ou choque séptico.23

O dano miocárdico subclínico pode ocorrer com a FEVE e a % D ainda normais que, quando alteradas, esse dano já seria irreversível.5,24–27 Com a intenção de aplicar métodos mais sensíveis, novas técnicas vêm sendo empregadas, entre elas está o Strain Longitudinal Global Longitudinal (SLG) para diagnóstico de disfunção subclínica com alta sensibilidade.5,24–27

No estudo, as complicações CV ocorreram em mais de 50% dos pacientes, e sabemos que dois de cada três sobreviventes podem ter alguma complicação cardiovascular até 30 anos após o tratamento oncológico.4,28

Na avaliação da associação dos fatores de risco com complicações CV do G2 (Tabela 2), a DC> 250mg/m2 não demonstrou significância, apesar de esse ser o principal fator de risco para cardiotoxicidade do G23,29e de quase 2/3 dos pacientes terem utilizado DC< 250mg/m2. As complicações CV do G2 não foram infrequentes (Tabelas 3 e 4), demonstrando que não existe dose segura, como também foi evidenciada a presença de alterações subclínicas pelo ecocardiograma com dose de antraciclinas de 100 mg/m2.2

Em estudos controlados em que o Dexrazoxano foi utilizado em todas as doses de antraciclinas, foi demonstrada a cardioproteção em relação ao grupo controle.2,6,7 Em nossas observações, o uso de Dexrazoxano não demonstrou significância estatística para cardioproteção, o que pode ser explicado pelo fato de que mais de 50% dos pacientes não utilizaram o cardioprotetor em todas as doses de antraciclinas conforme recomendações, sendo este um viés do nosso trabalho.30

Como mostrado na Tabela 3, ICC com uso de drogas vasoativas apresentou associação significativa com idade inferior a um ano, o que pode ser explicado pela imaturidade do sistema CV e a sensibilidade relativa das células mais jovens à quimioterapia.4 Ainda, a DS-VE associou-se significativamente com idade maior que 15 anos, o que pode ser explicado pela predominância de tumores que usam altas DC de antraciclinas.17 Na Tabela 4, apresentaram associação significativa com óbito – HAS, derrame pericárdico após início das antraciclinas e ICC com DVA – contudo, concordando com a literatura, no estudo, a recorrência com progressão da doença subjacente foi a principal causa de óbito.1

As complicações CVs são as complicações mais frequentes relacionadas ao tratamento antineoplásico são as CV. A avaliação cardiológica desde as fases iniciais do tratamento para estratificação de risco, a aplicação de protocolos de seguimento e a implementação de medidas preventivas são de fundamental importância.3,5 No estudo, cerca de 80% dos pacientes realizaram ecocardiograma antes do uso de antraciclinas, o mesmo não ocorreu em relação às consultas cardiológicas (Figura 1).

Este estudo apresenta algumas limitações a serem consideradas. O desenho retrospectivo e unicêntrico expõe o viés de informação e a inabilidade para controlar variáveis de confusão, (falta de informação). Assim, informações das complicações CVs poderiam estar subestimadas ao realizar avaliação ecocardiográfica com modo M (Teichholz), sendo que as recomendações orientam para avaliação volumétrica do ventrículo esquerdo (Simpson biplanar). No período estudado, a falta de outros métodos que auxiliam no diagnóstico de alterações subclínicas da função ventricular, como o ecocardiograma com strain, avaliação dos biomarcadores de lesão miocárdica, assim como a realização rotineira do eletrocardiograma, pode ter subestimado a incidência das complicações do G2 e de alterações do ritmo cardíaco.

Conclusões

Embora as complicações CVs relacionadas à disfunção ventricular sejam as mais graves, mais temidas e mais estudadas, o presente estudo mostrou que as gerais foram mais frequentes, denotando a necessidade dessas formas de apresentação serem incluídas nas estratégias de monitoramento e prevenção.

A alta DC de antraciclinas é o principal fator de risco para cardiotoxicidade relacionada à disfunção ventricular, mas não existe dose segura. O estudo reforça esse entendimento uma vez que 73,3% dos pacientes usaram DC < 250mg/m2 e mesmo assim essas complicações ocorreram em um de cada quatro pacientes.

Apesar das limitações, o estudo oportunizou um primeiro levantamento, já que existe uma escassez de trabalhos brasileiros publicados com análises das alterações CVs durante o tratamento quimioterápico na população infantojuvenil. Porém, o cenário clínico aqui apresentado certamente reproduz a realidade de outros centros de tratamento do câncer. Por isso, esperamos chamar a atenção para a necessidade do reconhecimento in loco das reais demandas, buscando instituir estratégias para o aprimoramento dos pontos fortes e o ajuste das deficiências identificadas.

Os dados encontrados neste estudo enfatizam a importância de uma parceria entre oncologistas e cardiologistas com formulação de estratégias de prevenção, diagnóstico, terapia precoce otimizada das diferentes formas de apresentação de cardiotoxicidade. Isso possibilitaria a continuidade do tratamento, uma melhor qualidade de vida futura, e uma redução das taxas de morbimortalidade.

Footnotes

Fontes de financiamento

O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Vinculação acadêmica

Este artigo é parte de dissertação de mestrado de Cristina Chaves dos Santos de Guerra pela Escola Superior em Ciências da Saúde.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética da Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa em Ciências da Saúde sob o número de protocolo 4.185.55. Todos os procedimentos envolvidos nesse estudo estão de acordo com a Declaração de Helsinki de 1975, atualizada em 2013.

Referências

- 1.Gudmundsdottir T, Winther JF, Licht SF, Bonnesen TG, Asdahl PH, Tryggvadottir L, et al. Cardiovascular Disease in Adult Life after Childhood Cancer in Scandinavia: A Population-based Cohort Study of 32,308 One-year Survivors. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(5):1176–1186. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchins KK, Siddeek H, Franco VI, Lipshultz SE. Prevention of Cardiotoxicity Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(3):455–465. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Muñoz DR, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. 2016 ESC Position Paper on Cancer Treatments and Cardiovascular Toxicity Developed Under the Auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for Cancer Treatments and Cardiovascular Toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37(36):2768–2801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seber A, Miachon AS, Tanaka AC, Castro AMS, Carvalho AC, Petrilli AS, et al. First Guidelines on Pediatric Cardio-oncology from the Brazilian Society of Cardiology. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;100(5 Suppl 1):1–68. doi: 10.5935/abc.2013S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajjar LA, Costa IBSDSD, Lopes MACQ, Hoff PMG, Diz MDPE, Fonseca SMR, et al. Brazilian Cardio-oncology Guideline - 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2020;115(5):1006–1043. doi: 10.36660/abc.20201006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harake D, Franco VI, Henkel JM, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE. Cardiotoxicity in Childhood Cancer Survivors: Strategies for Prevention and Management. Future Cardiol. 2012;8(4):647–670. doi: 10.2217/fca.12.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asselin BL, Devidas M, Chen L, Franco VI, Pullen J, Borowitz MJ, et al. Cardioprotection and Safety of Dexrazoxane in Patients Treated for Newly Diagnosed T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia or Advanced-Stage Lymphoblastic Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Report of the Children's Oncology Group Randomized Trial Pediatric Oncology Group 9404. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(8):854–862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groarke JD, Nohria A. Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity: A New Paradigm for an Old Classic. Circulation. 2015;131(22):1946–1949. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic Health Conditions in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh ET, Bickford CL. Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy: Incidence, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(24):2231–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Children's Oncology Group . Long-term Follow-up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer. Monrovia: Children's Oncology Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armenian S, Bhatia S. Predicting and Preventing Anthracycline-Related Cardiotoxicity. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:3–12. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_100015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instituto Nacional de Câncer . INCA: Ministério da Saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2019. [[2019 Jul 01]]. Available from: inca.gov.br . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutti CF, Cruz VG, Santos LF, Araújo D, Cogo SB, Neves ET. Perfil Clínico-epidemiológico de Crianças e Adolescentes com Câncer em um Serviço de Oncologia. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2018;64(3):293–300. doi: 10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2018v64n3.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedrosa AO, Lira R, Filho, Santos FJL, Gomes RNS, Monte LRS, Portela NLC. Perfil Clinico-epidemiológico de Clientes Pediátricos Oncológicos Atendidos em um Hospital de Referência do Piauí. Rev Interd. 2015;8(3):12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos BPM, Vittorazzi DR, Moulin GL, Faria MEF, Neves PP, Alves RS, et al. Epidemiologia do Câncer Infantojuvenil do Hospital Infantil Nossa Senhora da Glória nos anos de 2010 a 2015. Rev Esfera Acadêmica Saúde. 2016;1(2):113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Instituto Nacional de Câncer . Incidência, Mortalidade e Morbidade Hospitalar por Câncer em Crianças, Adolescentes e Adultos Jovens no Brasil: Informações dos Registros de Câncer e do Sistema de Mortalidade. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Saúde; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feliciano SVM, Santos MO, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS. Incidência e Mortalidade por Câncer entre Crianças e Adolescentes: Uma Revisão Narrativa. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2018;64(3):389–396. doi: 10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2018v64n3.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipshultz SE, Franco VI, Miller TL, Colan SD, Sallan SE. Cardiovascular Disease in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:161–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-070213-054849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assuncao BMBL, Handschumacher MD, Brunner AM, Yucel E, Bartko PE, Cheng KH, et al. Acute Leukemia is Associated with Cardiac Alterations before Chemotherapy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(11):1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumners JE, Johnson WW, Ainger LE. Childhood Leukemic Heart Disease. A Study of 116 Hearts of Children Dying of Leukemia. Circulation. 1969;40(4):575–581. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra P, Kapoor G, Jain S, Garg B. Incidence and Risk Factors for Hypertension During Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Therapy. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55(10):877–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pancera CF, Costa CM, Hayashi M, Lamelas RG, Camargo Bd. Sepse Grave e Choque Séptico em Crianças com Câncer: Fatores Preditores de Óbito. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2004;50(4):439–443. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302004000400037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curigliano G, Cardinale D, Dent S, Criscitiello C, Aseyev O, Lenihan D, et al. Cardiotoxicity of Anticancer Treatments: Epidemiology, Detection, and Management. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):309–325. doi: 10.3322/caac.21341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuzovic M, Wu PT, Kianmahd S, Nguyen KL. Natural History of Myocardial Deformation in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Exposed to Anthracyclines: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Echocardiography. 2018;35(7):922–934. doi: 10.1111/echo.13871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chow EJ, Leger KJ, Bhatt NS, Mulrooney DA, Ross CJ, Aggarwal S, et al. Paediatric Cardio-oncology: Epidemiology, Screening, Prevention, and Treatment. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(5):922–934. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu HM, Zhang XL, Zhang WL, Huang DS, Du ZD. Detection of Subclinical Anthracyclines’ Cardiotoxicity in Children with Solid Tumor. Chin Med J. 2018;131(12):1450–1456. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.233950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franco VI, Henkel JM, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE. Cardiovascular Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors Treated with Anthracyclines. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:134679–134679. doi: 10.4061/2011/134679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, Mertens AC, Mitby P, Stovall M, et al. Cardiac Outcomes in a Cohort of Adult Survivors of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer: Retrospective Analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Cohort. BMJ. 2009;339:4606–4606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu V. Dexrazoxane: a Cardioprotectant for Pediatric Cancer Patients Receiving Anthracyclines. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2015;32(3):178–184. doi: 10.1177/1043454214554008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]