Viral hepatitis is the major cause of chronic liver disease worldwide. An estimated 300 million people are carriers of the hepatitis B virus, and 120 million are infected with hepatitis C. Untreated, these infections may progress to cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatoma. Public health measures to limit new infection, including immunisation against hepatitis B and screening of blood products for hepatitis B and C viruses, have now been implemented in most developed countries and are being implemented in many developing counties.

This review focuses on the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C, which has undergone dramatic improvement in the past few years.

Summary points

Lamivudine is a safe effective antiviral drug for treating chronic hepatitis B virus infection

Lamivudine is most effective in patients with substantially elevated transaminase concentrations and those with advanced cirrhosis

Lamivudine treatment is hampered by the frequent development of resistance; in the near future combinations of antiviral agents may become standard treatment

Ribavirin in combination with interferon is effective for selected patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection

Overall, about 30-40% of all patients can expect to be cured by this treatment, and in selected subgroups of patients cure rates of 80-90% can be achieved

Treatment with interferon alfa (as part of combination therapy) reduces the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma and may partially reverse hepatic fibrosis

Methods

The information used in the preparation of this article was based on a Medline search to identify key papers in addition to searching abstracts from the meetings of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and European Association for the Study of the Liver between 1997 and 2001. Search terms included hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, treatment, lamivudine, tribavirin (ribavirin), interferon, pegylated interferon, and combination therapy.

Hepatitis B

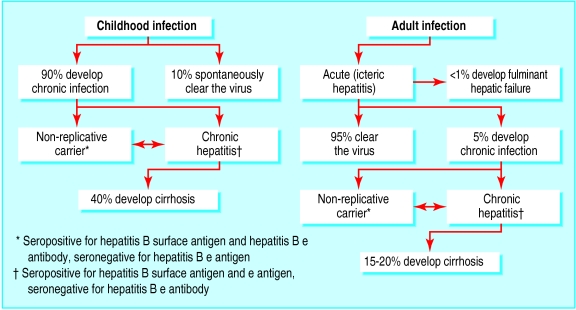

Of the world's 300 million people with chronic hepatitis B, most acquired the disease by vertical transmission or during preschool childhood. In the absence of vaccination (which can usually prevent neonatal infection) most exposed neonates and young children will be infected and become lifelong carriers (fig 1). Chronic infection, particularly of males, is often complicated by the eventual development of cirrhosis and then liver failure or hepatoma. In contrast, primary exposure of adults to hepatitis B virus typically causes acute resolving infection with clearance of the virus (fig 1).

Figure 1.

Natural course of primary hepatitis B infection acquired during childhood or adulthood

In the United Kingdom, as in most developed countries, chronic hepatitis B is uncommon. As many as 4% of the general population have serological evidence of exposure to the virus,1 but as few as 0.4% of the population (240 000 people) have chronic infection.1,2

Treatment

Interferon

Until recently, interferon alfa was the only drug licensed for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Interferon treatment is intended to inhibit viral replication (a direct suppressive effect) and to augment the clearance of virally infected hepatocytes. Among patients with chronic infection, about 5% a year undergo spontaneous conversion from a state of high level viral replication (reflected by the presence in serum of hepatitis B e antigen, a marker of high level replication) to low level replication (reflected by the disappearance of the e antigen and appearance of antibodies to the antigen). Interferon treatment (5 million units three times weekly for four to six months) increases the conversion rate from high level to low level viral replication in up to 15-20% of patients a year. Response rates are enhanced by higher doses, but the safety and tolerability of high dose interferon are a concern.

Lamivudine

In 1999 lamivudine was licensed in many countries for treating selected patients with chronic hepatitis B. It is a nucleoside analogue that inhibits the viral polymerase and reduces virus production 100-1000 times. This is associated with improvement of liver function tests and liver histology.3 In addition to its suppressing viral replication in all patients, it increases the conversion rate from high level to low level viral replication by a similar amount to that achieved by interferon. The probability of conversion to low level viral replication during lamivudine treatment is proportional to the amount of liver inflammation before treatment. When pretreatment inflammation is severe conversion is more likely.4

Lamivudine is well tolerated by most patients. In placebo controlled clinical trials the side effect profiles of lamivudine and placebo were almost identical.5 Thus, lamivudine is preferred to interferon by most clinicians for the initial treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B. For patients with cirrhosis and high levels of viral replication, interferon treatment may be associated with a flare of hepatitis and decompensation of advanced cirrhosis. Lamivudine, however, seems to be safe for these patients, and the suppression of viral replication achieved may be associated with substantial clinical improvement.6,7

If liver failure persists despite treatment, or if liver cancer has developed, liver transplantation may be the preferred treatment. Until recently, many liver transplant centres denied transplantation to patients with hepatitis B because of concern about graft reinfection with the virus resulting in early organ loss. Now, however, lamivudine treatment effectively prevents viral reinfection of the graft after liver transplantation.8

As is seen during treatment of HIV infection, potent prolonged antiviral treatment of hepatitis B selects for viral species or variants that are naturally resistant to treatment. Emergence of lamivudine resistant virus is seen in about 15-25% of treated patients after 12 months treatment, and may be an inevitable development during prolonged treatment (fig 2). Fortunately, new antiviral drugs are at advanced stages of development. For example, the nucleotide analogue adefovir is a potent inhibitor of hepatitis B virus replication and retains activity against lamivudine resistant species,9 suggesting that the combination of lamivudine with adefovir may provide potent sustained inhibition of viral replication.

Figure 2.

Outcome of prolonged treatment with lamivudine in patients with hepatitis B

Initial studies of treating chronic hepatitis B with combined interferon and lamivudine suggest that this treatment has greater efficacy than either drug alone.10,11 However, marginal improvement of efficacy needs to be balanced by considerations of tolerability, safety, and cost of this combination of drugs. Since most treated patients will require long term, probably indefinite, suppression of viral replication, future treatment schedules must aim for safe and tolerable drug combinations.

Recommendation

Decisions about treatment depend to a large degree on the availability of lamivudine and the healthcare resources of the society. In many poorer countries the availability of lamivudine, and interferon, will be greatly limited by their cost. In these circumstances no treatment will be available for patients with hepatitis B, and healthcare measures will be limited to public education, immunisation against hepatitis B, and screening of blood products.

Ideally, all patients with chronic hepatitis B should be evaluated by a doctor experienced in the disease. Patients with active chronic infection with evidence of ongoing liver damage and high level viral replication should be considered for lamivudine treatment. Treatment of patients seropositive for hepatitis B e antigen should continue until they convert from high level viral replication to low level replication. Eventually, either conversion is achieved or drug resistant viral species emerge without conversion. Either outcome constitutes an indication to stop lamivudine. During treatment, patients should be reviewed every three to six months. At each attendance, serum hepatitis B e antigen, e antibody, and viral DNA titre should be measured. These data permit identification of patients who have achieved a treatment end point. The management of lamivudine resistant hepatitis B is the realm of the specialist and will depend on the future availability of new treatments.

Hepatitis C

The estimated prevalence of hepatitis C in the United Kingdom is between 200 000 and 400 000 people, but varies greatly between subgroups of the population—0.04% of blood donors, 0.4-0.6% of antenatal attendants in London,12 and up to 50% of intravenous drug users. About 85% of those infected with the virus develop chronic infection. The natural course of chronic hepatitis C is now well described. Untreated, a substantial proportion of infected people will develop cirrhosis, and many will die of its complications (fig 3). Hepatitis C induced cirrhosis is now the most common indication for liver transplantation in most countries.

Figure 3.

Natural course of hepatitis C infection

Treatment

Until the mid-1990s, interferon alfa was the only available treatment. Monotherapy with interferon seldom achieved eradication of infection. Early studies defined the important role of viral genotype (natural variants of the hepatitis C virus) as a determinant of response to treatment.13 For those infected by virus with unfavourable genotypes, the response rate to interferon monotherapy was less than 10%.13

The addition of ribavirin, a nucleoside analogue, to interferon treatment has substantially improved the response, although viral genotype remains an important determinant of response rate.14 Overall, about 30-40% of all patients can expect to be cured (sustained viral clearance) by the combination of interferon and ribavirin. In selected subgroups of patients cure rates of 80-90% can be achieved. Cure prevents the development of cirrhosis and its complications. In October 2000 the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) supported the use of combination therapy (in preference to interferon monotherapy) for patients who have substantial histological damage due to hepatitis C (www.nice.org.uk). All patients with evidence of chronic infection who are likely to be compliant with 6-12 months of intense medical therapy should be referred to an appropriate specialist for consideration of treatment.

Recently, a new preparation of interferon, peginterferon alfa (polyethylene glycol conjugated “pegylated” interferon), has been evaluated alone and in combination with ribavirin as treatment for hepatitis C. Studies suggest that peginterferon may have greater efficacy than standard interferon.15 The greater efficacy may be explained in part by the more rational approach to interferon dosing (weight adjusted) suggested for peginterferon (compared with fixed dosing regimens adopted for standard interferon).

Benefits of treatment

Although cure remains the primary objective, the benefits of treatment are not necessarily restricted to those patients who achieve eradication of the hepatitis C virus. It seems that interferon treatment (alone or in combination) may prevent progression of, or even reverse, hepatic fibrosis in infected patients even if cure is not achieved.16

Additional educational resources

Larson AM, Carithers RL. Hepatitis C in clinical practice. J Intern Med 2001;249:111-20

Lin OS, Keeffe EB. Current treatment strategies for chronic hepatitis B and C. Annu Rev Med 2001;52:29-49

Online resources

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Hepatitis publications. www.niddk.nih.gov/health/digest/pubs/hep/ (accessed 14 Sep 2001)

Haemophilia Society. Hepatitis C services. www.haemophilia.org.uk/services/hepatitis.html (accessed 14 Sep 2001)

National Center for Infectious Diseases. Viral hepatitis. www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hepatitis/index.htm (accessed 14 Sep 2001)

Hepatoma is a common complication of cirrhosis due to hepatitis C, occurring in up to 4% of cirrhotic patients a year. In most cases, by the time of diagnosis, the disease is too advanced to offer curative liver resection or liver transplantation. Persuasive evidence is now emerging that interferon treatment (alone or in combination) may substantially reduce the risk of developing hepatoma (fig 4). The effect is most apparent in those patients who are cured of infection but is also evident in patients who fail to clear the virus.17,18

Figure 4.

Liver with cirrhosis due to hepatitis C and large hepatoma

The standard duration of combination treatment is 6-12 months. The duration is dependent on pretreatment clinical and virological features. Persisting serum virus positivity despite six months of treatment identifies those patients who will not be cured by ongoing antiviral therapy. However, end points other than virological cure may become acceptable. For example, continued treatment despite persisting virus seropositivity might retard or prevent the development of cirrhosis and its attendant complications, including liver cancer. Pending the emergence of more potent antiviral drugs, young patients with advanced liver fibrosis and resistant viral genotypes might be suitable for this type of suppressive treatment.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: PJG has received a fee from GlaxoSmithKline (manufacturer of lamivudine) for speaking on the treatment of chronic hepatitis.

References

- 1.Gay NJ, Hesketh LM, Osborne KP, Farrington CP, Morgan-Capner P, Miller E. The prevalence of hepatitis B infection in adults in England and Wales. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:133–138. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham R, Northwood JL, Kelly CD, Boxall EH, Andrews NJ. Routine antenatal screening for hepatitis B using pooled sera: validation and review of 10 years experience. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:392–395. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.5.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai CL, Chien RN, Leung NW, Chang TT, Guan R, Tai DI, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien RN, Liaw YF, Atkins M. Pretherapy alanine transaminase level as a determinant for hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion during lamivudine therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Asian Hepatitis Lamivudine Trial Group. Hepatology. 1999;30:770–774. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tassopoulos NC, Volpes R, Pastore G, Heathcote J, Buti M, Goldin RD, et al. Efficacy of lamivudine in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative/hepatitis B virus DNA-positive (precore mutant) chronic hepatitis B. Lamivudine Precore Mutant Study Group. Hepatology. 1999;29:889–896. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sponseller CA, Bacon BR, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical improvement in patients with decompensated liver disease caused by hepatitis B after treatment with lamivudine. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:715–720. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.18501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villeneuve JP, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, et al. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;31:207–210. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mutimer D, Dusheiko G, Barrett C, Grellier L, Ahmed M, Anschuetz G, et al. Lamivudine without HBIg for prevention of graft reinfection by hepatitis B: long-term follow-up. Transplantation. 2000;70:809–815. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perillo R, Schiff E, Yoshida E, Statler A, Hirsch K, Wright T, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B mutants. Hepatology. 2000;32:129–134. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schalm SW, Heathcote J, Cianciara J, Farrell G, Sherman M, Willems B, et al. Lamivudine and alpha interferon combination treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: a randomised trial. Gut. 2000;46:562–568. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.4.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mutimer D, Dowling D, Cane P, Ratcliffe D, Tang H, O'Donnell K, et al. Additive antiviral effects of lamivudine and alpha-interferon in chronic hepatitis B infection. Antivir Ther. 2000;5:273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward C, Tudor-Williams G, Cotzias T, Hargreaves S, Regan L, Foster GR. Prevalence of hepatitis C among pregnant women attending an inner London obstetric department: uptake and acceptability of named antenatal testing. Gut. 2000;47:277–280. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hino K, Sainokami S, Shimoda K, Iino S, Wang Y, Okamoto H, et al. Genotypes and titers of hepatitis C virus for predicting response to interferon in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1994;42:299–305. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890420318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT) Lancet. 1998;352:1426–1432. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy KR, Wright TL, Pockros PJ, Shiffman M, Everson G, Reindollar R, et al. Efficacy and safety of pegylated (40-kd) interferon alpha-2a compared with interferon alpha-2a in noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;33:433–438. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poynard T, McHutchison J, Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Goodman Z, Bedossa P, et al. Impact of interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin on progression of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2000;32:1131–1137. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka H, Tsukuma H, Kasahara A, Hayashi N, Yoshihara H, Masuzawa M, et al. Effect of interferon therapy on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality of patients with chronic hepatitis C: a retrospective cohort study of 738 patients. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:741–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue A, Tsukuma H, Oshima A, Yabuuchi T, Nakao M, Matsunaga T, et al. Effectiveness of interferon therapy for reducing the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with type C chronic hepatitis. J Epidemiol. 2000;10:234–240. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]