Molecular investigation of an outbreak of HIV at Glenochil Prison contributed to the conviction of a former Glenochil drug injector, Mr Stephen Kelly, for culpably and recklessly transmitting HIV to a female sexual partner. We explain why the case of R v Kelly has brought the medical and legal professions into conflict and explore its implications for public health and molecular science in Scotland. Firstly, even a modest decline in the uptake of HIV testing by those who are actually infected could herald a one third increase in new sexually transmitted HIV infections. Secondly, there is now need for a national proforma to assure the quality and legality of HIV counselling in Scotland as a safeguard for both counsellors and clients. Thirdly, we discuss curtailment of molecular research investigations with the potential to discover incriminating evidence about HIV transmissions unless laboratory protocols, or legal safeguards, can be designed which obviate deductive disclosure about individuals. Urgent review by the Scottish Executive is required to minimise negative impacts of the Glenochil judgement on public health and molecular science.

Summary points

Knowingly transmitting HIV is a criminal offence in Scotland as a result of the Glenochil judgment

Even a modest fall in the uptake of HIV testing as a result of the judgment could produce a one third increase in new sexually transmitted HIV infections

A national proforma is needed to assure the quality and legality of HIV counselling in Scotland as a safeguard for both counsellors and clients

Molecular research investigations may be hampered because of the ability of the police to use them to discover incriminating evidence about HIV transmissions

The Scottish Executive needs to take urgent steps to minimise the negative effects of the Glenochil judgment on public health and molecular science

Glenochil judgment

Stephen Kelly was one of at least 14 drug injectors who became infected with HIV by needle sharing in Glenochil Prison, Scotland, in the first half of 1993.1–3 In June 1993, because of self assessed HIV risk, he participated in the infection control exercise at the prison.1,4 He accepted HIV counselling and testing from an outside counsellor, who informed him of his HIV diagnosis and gave post-test counselling on the day of his wife's funeral.

Subsequently, molecular research studies showed that 13 of the 14 drug injecting prisoners and a female heterosexual contact had the same strain of virus.3 Mr Kelly, one of the 13, is now serving five years' imprisonment for culpably and recklessly transmitting HIV infection to Miss Anne Craig, the above heterosexual contact. This is a harsh sentence by international standards.5 In early 1994, he and Miss Craig had unprotected vaginal and anal intercourse over at most two months before she seroconverted. He had not disclosed his HIV diagnosis.

Anal intercourse within two months of the start of a heterosexual relationship is relatively uncommon.6–7 And it was not discovered until after 1994 that the risk of transmitting HIV from male to female was quantified as being 20 times greater by penile-anal sex than by vaginal sex8,9 and 200 times greater if intercourse occurs during the first three months of HIV infection.9 This information was therefore not included in Mr Kelly's counselling.

Miss Craig, mother of three children (the youngest then 2 years old), had not had sexual relations since separating from her husband in 1990. Like a quarter of women in her age group,6 she relied for her sexual health on her partner's denial of any reason, other than avoidance of pregnancy, that they needed to use protection. She knew Mr Kelly had a history of drug injecting and imprisonment.

Notification of HIV, testing, and infection control

HIV infection is not notifiable in the United Kingdom. Prejudice about the condition, especially in the 1980s, led experts to believe that infection control would be better served by prioritising confidentiality for people infected with HIV. By encouraging HIV counselling and testing, doctors hoped that risk behaviours could be altered, especially after a positive diagnosis.

There was, and is, no compulsion to be tested. Patients can refuse to give a blood sample for HIV testing even after a healthcare worker has had a percutaneous injury and are not obliged to disclose their HIV status before surgery. Newly diagnosed patients do not have to disclose to healthcare workers the contact details for unsafe sexual or injecting partners for the period when they became infected. Notification of current partners has been done mainly by the patient, and notification of past partners, whether by patient or healthcare worker, is rarely done well.10,11 Use of condoms to prevent sexual transmission of HIV has been promoted as everyone's responsibility and as the only protection that individuals have against undiagnosed or undisclosed HIV infection. Thus, in practice in the United Kingdom, the confidentiality of the index patient has had priority over informing and safeguarding contacts—be they healthcare workers, drug injectors, or sexual partners.

Effect of judgment on testing and infection control

The Kelly verdict has criminalised undeclared, but not untested, HIV transmission. In Scotland, it is now a crime for someone who knows that they are HIV positive and conceals the knowledge to have unprotected sexual contact with another person and transmit HIV infection. Knowledge of HIV status, which was formerly a measure to reduce risk, can now endanger a person's liberty in a way that ignorance of it cannot. Yet ignorance is substantially more dangerous. Even in the era of highly active antiretroviral drugs, over 40% of people with a recent HIV diagnosis in Scotland have a first CD4 count of 200 or less, indicating longstanding unsuspected infection.12,13 Also, at least one fifth of unsafe sexual contacts of patients with newly diagnosed HIV are likely to be infected with HIV.10,14 Notification of partners can alert these people to their risk of HIV infection, but they can refuse an HIV test and thereby, despite knowing their high HIV risk, transmit HIV infection with impunity before the law.

The judgment leaves doubt about which behaviours are criminal. Is it a crime for someone who conceals their HIV infection to have unprotected intercourse if HIV transmission does not occur? Could someone who conceals their HIV infection be prosecuted if they have protected intercourse that results in HIV transmission because, for example, a condom breaks? Analogy with other crimes against the person suggests both could be crimes, as is the case in Canada.15 We also do not know whether transmission of other known, but not admitted, sexually transmitted infections qualifies as a crime against the person. If untreated, some cause serious long term injury. And is it a crime, not just contraindicated, for an HIV infected mother in the United Kingdom to breast feed her uninfected baby? Serious confusion about legalities can only negatively impact on efforts to improve sexual and public health in Scotland, as we illustrate below for new HIV infections.

Assessing the effect on new HIV infections

Scotland has an excellent HIV surveillance system. It therefore has the opportunity to quantify the effect of the Glenochil judgment on a range of HIV indicators including uptake of HIV testing by infected people in sentinel groups, numbers of diagnoses of HIV within 24 months of last negative HIV test result, numbers of recent HIV infections as judged by first CD4 count above 650, and compliance with routine notification of partners.10 The numbers of drug injectors having HIV tests in Scotland rose from 1476 in 1996 to 2430 in 1999.16 Such tests resulted in 16 diagnoses in 1999.12

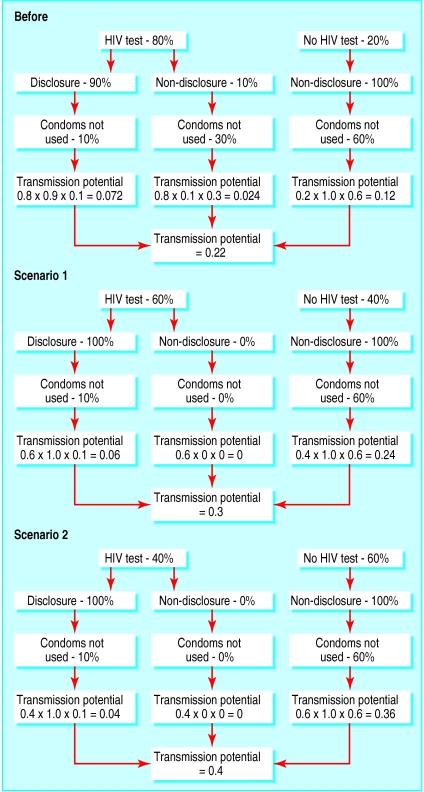

Miss Craig had hoped to prevent even one new infection.5 By contrast, the figure shows the plausible scenarios for reduced uptake of HIV tests by people infected with HIV, who may now be more reluctant to be tested. A 25% decrease in uptake of HIV testing by those who are infected could result in more than a one third increase in new sexually transmitted HIV infections—even if, in accordance with the Glenochil judgment, those tested always disclosed their infection to sexual partners. If uptake of HIV tests fell as low as 40% (the uptake among Glenochil prisoners at the time of the infection control exercise1,17) new sexually transmitted infections might almost double.

Although our figure offers a guide to risk assessment, the key probabilities of HIV test uptake, disclosure, and condom use by people infected with HIV before and after Glenochil judgment need to be estimated appropriately for Scotland. We urge Scotland's health minister to commission the necessary measurements to guide medical and legal decision making. This is a more responsible approach than waiting passively until we have evidence that infectious harm has been done.

Quality and content of HIV counselling: need for national proforma?

High uptake of HIV testing by people with high exposure to HIV is one measure of the quality of HIV counselling.18,19 Other measures include curtailing spread of HIV infection by counselled or diagnosed people (which molecular investigations can shed light on); limiting the HIV infection rate among counselled clients who have tested HIV antibody negative (to which data from Scotland's denominator study gives insight16); and random follow up to audit risk perceptions and behaviour change among those counselled (according to whether they elected to have an HIV test).

The infection control exercise at Glenochil Prison in 1993 did not score highly on these measures.1,17 It was limited to the prison's 378 adult inmates on 28 June 1993, of whom only 162 (43%) had an HIV test. Some members of the counselling team were ambivalent about the benefits of HIV diagnosis during incarceration,4 and the fact that 258 other men who had been in Glenochil Prison during January to June 1993 were not contacted places a question mark over its score on the last two of our quality measures.

In future, the quality of HIV counselling may matter in law in Scotland. To safeguard both HIV counsellors and clients, a national proforma needs to be drawn up to assist in eliciting and reducing risk behaviours, working out the index patient's seroconversion interval (time between last known negative date to earliest HIV positive date), and documenting HIV exposures (HIV seroconversion illness, condom breakage, assault, etc). If exposure occurred after the infector's HIV diagnosis, it now matters in criminal justice terms, whether HIV had been disclosed to the patient.

The proforma for use by both HIV counsellors and clients should explain in plain language the legal ramifications of the Glenochil judgment. It may have to advise people to disclose their HIV infection to sexual (and injecting) partners before two witnesses. The Cuerrier judgment in Canada has made HIV disclosure to sexual partners obligatory in law, even if condoms are used always.15 Written guidance to and from HIV counsellors makes this clear to clients.

Effect on molecular epidemiology

Molecular epidemiology has enormous potential to discover, document, and sensitively interrupt HIV (and other) transmission networks. But the ability of the police to obtain a warrant to access unnamed molecular research data in the case of R v Kelly has made this information forensic evidence.20 Informed consent notwithstanding, can doctors and scientists continue to appeal to patients, especially prisoners, to contribute samples for molecular studies when there is a risk that incriminating evidence will be discovered?

Three follow up studies on the Glenochil outbreak were not pursued because they had the potential to give incriminating evidence about secondary transmission of the Glenochil virus to male injectors outside Glenochil, to female injectors, or to women with a male injector as sexual partner. But because an estimated 30% of HIV infections in the Glenochil outbreak were not diagnosed at the time,2 a follow up study to discover the “missing” Glenochil infections was instigated. It periodically matched the master indices (first initial, soundex of surname,21 sex, and date of birth) for the 636 inmates of Glenochil Prison during January to June 1993 against the similarly indexed HIV register for Scotland.22,23 This study, which had just completed matching to the end of January 2001, has now been halted. Patients with HIV whose master index matches with someone on the Glenochil list will not be approached.

Conclusion

Far from protecting the public, the Glenochil judgment has endorsed abrogation of individual responsibility in sexual partnerships by asserting a legal duty of disclosure on the infected partner. It is likely to undermine uptake of HIV testing and risks a one third increase in new HIV infections in Scotland. The effect of the judgment on HIV counselling is also substantial.17 A national proforma is required for use by HIV counsellors and clients in Scotland that properly explains the legal situation. The dual goals of notifying partners (HIV prevention and earlier diagnosis and treatment) have also been seriously threatened. The prosecution of Mr Kelly has also underlined the need for research scientists to anticipate that potentially incriminating results, even in unlabelled studies, may be followed up by forensic requests from individual study participants or by police warrant.24,25 We believe that urgent review by the Scottish Executive is required to minimise the negative effects on public health and molecular science.

Figure.

Effect of different uptakes of HIV testing and disclosure rates on transmission of HIV (uptake before Glenochil judgment and 25% reduction in uptake (scenario 1) and 50% reduction in uptake (scenario 2) after the judgment)

Footnotes

Competing interests: AJLB was an expert witness in the case of R v Kelly. SMB helped devise a method of HIV surveillance that guarantees anonymity for prisoners. She holds shares in GlaxoSmithKline and has academic links with the Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health.

References

- 1.Taylor A, Goldberg D, Emslie J, Wrench J, Gruer L, Cameron S, et al. Outbreak of HIV infection in a Scottish prison. BMJ. 1995;310:289–292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6975.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gore SM, Bird AG, Burns SM, Goldberg DJ, Ross AJ, Macgregor J. Drug injection and HIV prevalence in inmates of Glenochil prison. BMJ. 1995;310:293–296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6975.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yirrell DL, Robertson P, Goldberg DJ, McMenamin J, Cameron S, Leigh Brown AJ. Molecular investigation into outbreak of HIV in a Scottish prison. BMJ. 1997;314:1446–1450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg D, Taylor A, McGregor J, Davis B, Wrench J, Gruer L. A lasting public health response to an outbreak of HIV infection in a Scottish prison? Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9:25–30. doi: 10.1258/0956462981921602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLaren L. We all still need to be loved. Herald 2001;March 17:10.

- 6.Wellings K, Field J, Johnson AM, Wadsworth J. Sexual behaviour in Britain. The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. London: Penguin Books; 1994. p. 155. , 359. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misegades L, Page-Shafer K, Halperin D, McFarlane W YWS Study investigators' Group. Anal intercourse among young low-income women in California: an overlooked risk factor for HIV? AIDS. 2001;15:534–535. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200103090-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fielding KL, Brettle RP, Gore SM, O'Brien F, Wyld R, Robertson JR, et al. Heterosexual transmission of HIV analysed by generalized estimating equations. Stat Med. 1995;14:1365–1378. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leynaert B, Downs AM, de Vincenzi I European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Variability of infectivity throughout the course of infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:88–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mir N, Scoular A, Lee K, Taylor A, Bird S, Hutchinson S, et al. Partner notification in HIV-1 infection: a population based evaluation of process and outcomes in Scotland. Sexually Transmitted Infections (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Pattman RS, Gould EM. Partner notification for HIV infection in the United Kingdom: a look back on seven years' experience in Newcastle upon Tyne. Genitourinary Med. 1993;69:94–97. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HIV infection and AIDS: quarterly reports to 31 December 2000 and 31 March 2001. Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Weekly Reports. 2001;35:24. , 100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.HIV infection and AIDS: quarterly reports to 31 March 2000 and 30 September 2000. Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Weekly Reports. 2000;34:92. , 264. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Partner Notification Study Group. Recently diagnosed sexually HIV-infected patients: seroconversion interval, partner notification period and high yield of HIV diagnoses among partners. Q J Med (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Elliott R. Supreme Court rules in R v Cuerrier. Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Newsletter. 1999;4(2/3):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HIV infection and severe HIV-related disease in Scotland 1999. Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Weekly Reports. 2000;34:S1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gore SM, Bird AG. No escape: HIV transmission in jail. Prisons need protocols for HIV outbreaks. BMJ. 1993;307:147–148. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6897.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird AG, Gore SM, Leigh Brown AJ, Carter DC. Escape from collective denial: HIV transmission during surgery BMJ 1991;303:351-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Bird AG, Gore SM. Revised guidelines for HIV infected healthcare workers. BMJ. 1993;306:1013–1014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6884.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyer C. Use of confidential HIV data helps convict former prisoner. BMJ. 2001;322:633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CD4 Collaborative Group. Use of monitored CD4 counts: predictions of the AIDS epidemic in Scotland. AIDS. 1992;6:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson SJ, Gore SM, Goldberg DJ, Yirrell DL, McGregor J, Bird AG, et al. Method used to identify previously undiagnosed infections in the HIV outbreak at Glenochil prison. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;123:271–275. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yirrell DL, Hutchinson SJ, Griffin M, Gore SM, Leigh Brown AJ, Goldberg DJ. Completing the molecular investigation into the HIV outbreak at Glenochil prison. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;173:277–282. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UK Collaborative Group on Monitoring the transmission of HIV Drug Resistance. Analysis of prevalence of HIV-1 drug resistance in primary infections in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 2001;322:1087–1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medical Research Council. MRC executive summary: personal information in medical research. London: MRC; 2000. [Google Scholar]