Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the short-term outcomes and safety profiles of androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT)+abiraterone/prednisone with those of ADT+docetaxel in patients with de novo metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC).

Materials and Methods

A web-based database system was established to collect prospective cohort data for patients with mHSPC in Korea. From May 2019 to November 2022, 928 patients with mHSPC from 15 institutions were enrolled. Among these patients, data from 122 patients who received ADT+abiraterone/prednisone or ADT+docetaxel as the primary systemic treatment for mHSPC were collected. The patients were divided into two groups: ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group (n=102) and ADT+docetaxel group (n=20). We compared the demographic characteristics, medical histories, baseline cancer status, initial laboratory tests, metastatic burden, oncological outcomes for mHSPC, progression after mHSPC treatment, adverse effects, follow-up, and survival data between the two groups.

Results

No significant differences in the demographic characteristics, medical histories, metastatic burden, and baseline cancer status were observed between the two groups. The ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group had a lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression rate (7.8% vs. 30.0%; p=0.011) and lower systemic treatment discontinuation rate (22.5% vs. 45.0%; p=0.037). No significant differences in adverse effects, oncological outcomes, and total follow-up period were observed between the two groups.

Conclusions

ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had lower PSA progression and systemic treatment discontinuation rates than ADT+docetaxel. In conclusion, further studies involving larger, double-blinded randomized trials with extended follow-up periods are necessary.

Keywords: Abiraterone acetate, Adverse effects, Docetaxel, Prostatic neoplasms, Treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

According to the recent global cancer statistics report, 1,414,259 (7.3%) individuals were newly diagnosed with prostate cancer, and 375,304 (3.8%) individuals died from prostate cancer worldwide in 2020 [1]. Although the age-standardized incidence rate of prostate cancer was lower in Korea than in Europe and America, prostate cancer is the third most common malignancy among males in Korea [1,2]. According to the Korea Central Cancer Registry, in 2019, the age-standardized incidence of prostate cancer was steadily increasing [3]. Approximately 6% to 10% of patients with prostate cancer had distant metastases at diagnosis [2,4]. The 5-year relative survival rate for localized and regional prostate cancer was nearly 100%; however, the 5-year relative survival rate for metastatic prostate cancer was only 30% to 45.9% [2,4].

Several clinical trials on de novo metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) have been conducted, and both androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT)+docetaxel and ADT+abiraterone/prednisone therapies can improve overall survival (OS) compared with ADT alone [5]. Recently, two clinical trials have shown that triplet therapy was associated with longer OS compared with ADT+docetaxel [6]. A network meta-analysis compared triplet with doublet therapy in mHSPC and demonstrated that darolutamide+docetaxel+ADT had longer OS than that with ADT+androgen receptor axis-targeted agents in high-volume mHSPC [6].

A meta-analysis and a few clinical studies have compared the efficacy of ADT+docetaxel with that of ADT+abiraterone/prednisone in patients with mHSPC [7,8,9,10]. However, only one multi-institutional study has been conducted, and all studies were not conducted in Korea [8,9,10]. Considering the pathological aggressiveness of Korean patients with prostate cancer in a retrospective cohort study for clinically localized prostate cancer, directly applying the results of these clinical trials is difficult [11]. To solve this problem, a web-based database system was established to collect the basic demographic and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with mHSPC from multiple centers in Korea. To investigate the short-term clinical results and safety profiles of the two treatments currently used in mHSPC, the data of patients treated with ADT+docetaxel and ADT+abiraterone/prednisone were selected from the database and were analyzed to compare the two treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board of Kyungpook National University School of Medicine, Daegu, Republic of Korea (IRB Number 2019-06-015) approved this trial. The study was conducted according to the relevant laws and regulations, good clinical practices, and ethical principles, as described in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all study subjects.

2. Description of participants

A web-based database system was established to collect retrospective and prospective cohort data of patients with mHSPC from several institutions in Korea. The inclusion criteria of the database system were as follows: (i) patients with pathologically confirmed prostate cancer; (ii) those diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer within 12 months at the time of enrollment; and (iii) those whose basic information could be checked before or after the initiation of the first treatment for mHSPC. The exclusion criteria of the database system were as follows: (i) patients who did not provide consent to the enrollment in this study, including patients or protectors who cannot read or understand Korean, making it impossible to sign the consent form.

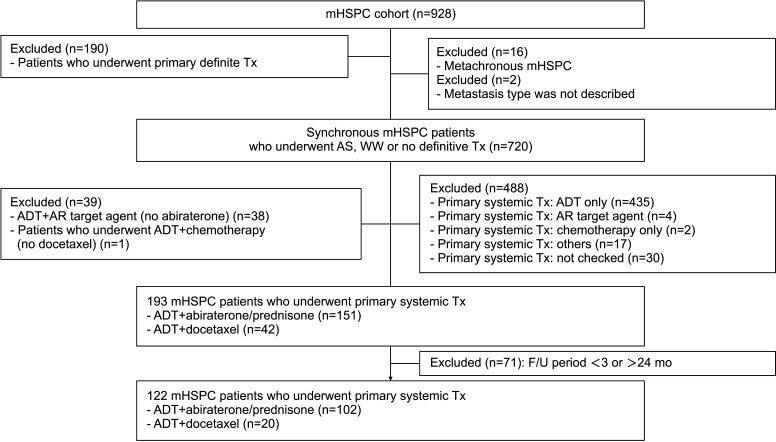

From May 2019 to November 2022, 928 patients with mHSPC from 15 institutions in Korea were enrolled. Among these patients in a prospective cohort study on metastatic prostate cancer, data from 122 patients who received ADT+abiraterone/prednisone or ADT+docetaxel as the primary systemic treatment for mHSPC were collected. The patients were divided into two groups: ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group (n=102) and ADT+docetaxel group (n=20) (Fig. 1). In the ADT+docetaxel group, the cycles and dosage were not completely recorded in eight cases (40.0%). Among patients with complete records (n=12), most of docetaxel chemotherapy was a triweekly regimen, and six cycles (9/12, 75.0%) was the most common. We compared the demographic characteristics, medical histories, baseline cancer status, initial laboratory tests, metastatic burden, oncological outcome for mHSPC, progression after mHSPC treatment, adverse effects, and follow-up and survival data between the two groups.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the study population enrollment. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy, AR: androgen receptor, mHSPC: metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, WW: watchful waiting, AS: active surveillance, Tx: treatment, F/U: follow-up.

3. Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were used. progression-free survival (PFS) rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 29.0 (IBM Corp.), and differences with p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The demographic characteristics and past medical history of the study population were not significantly different between the two groups. No significant difference in the baseline cancer status was observed between the two groups. The median prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level at the initial diagnosis was 142.7 ng/mL (Table 1, Supplement Table 1, 2).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics, past medical history, and baseline cancer status of the study population.

| Variable | Total (n=122) | ADT+abiraterone (n=102) | ADT+docetaxel (n=20) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 68.9±8.3 | 69.5±8.3 | 65.8±7.8 | 0.065 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.9±2.9 | 23.8±3.0 | 24.7±2.4 | 0.199 | |

| ECOG PS | 0.777 | ||||

| 0 | 94 (77.0) | 79 (77.5) | 15 (75.0) | ||

| ≥1 | 28 (23.0) | 23 (22.5) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| DM | 23 (18.9) | 18 (17.6) | 5 (25.0) | 0.684 | |

| Hypertension | 58 (47.5) | 44 (43.1) | 14 (70.0) | 0.086 | |

| PSA at initial diagnosis (ng/mL) | 142.7 (54.7–626.3) | 150.0 (55.5–651.0) | 100.0 (52.7–604.7) | 0.596 | |

| PSA at metastasis (ng/mL) | 151.6 (57.4–626.3) | 161.6 (62.6–664.8) | 86.0 (44.2–500.0) | 0.292 | |

| Testosterone at metastasis (ng/mL) | 3.3 (2.6–4.8) | 3.7 (2.7–5.7) | 2.8 (2.6–3.4) | 0.192 | |

| Clinical tumor stage | 0.083 | ||||

| ≤T3a | 16 (13.1) | 10 (9.8) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| T3b | 42 (34.4) | 36 (35.3) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| T4 | 59 (48.4) | 51 (50.0) | 8 (40.0) | ||

| Unknown | 5 (5.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Gleason score | 0.695 | ||||

| ≤8 | 60 (49.2) | 51 (50.0) | 9 (45.0) | ||

| ≥9 | 59 (48.4) | 49 (48.0) | 10 (50.0) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (2.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| % Of positive cores | 91.7 (60.7–100.0) | 90.3 (58.3–100.0) | 95.8 (71.1–100.0) | 0.215 | |

| Max. rate (%) | 90.0 (75.0–100.0) | 90.0 (75.0–100.0) | 91.9 (80.6–100.0) | 0.285 | |

Values are presented as means±standard deviations, medians (interquartile ranges), or numbers (%), unless otherwise indicated.

ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy, BMI: body mass index, DM: diabetes mellitus, ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, PSA: prostate-specific antigen, Max: maximum.

Regarding the initial laboratory tests, the ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group had lower total bilirubin (0.6 mg/dL vs. 0.8 mg/dL; p=0.044), alkaline phosphatase (117.0 IU/L vs. 192.0 IU/L; p=0.029), and aspartate aminotransferase (23.0 IU/L vs. 29.5 IU/L; p=0.034) levels. Meanwhile, no significant differences in the other laboratory tests were observed between the two groups (Supplement Table 3).

Furthermore, no significant difference in the mHSPC metastatic burden was observed between the two groups. Regarding oncological outcomes, the ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group had lower PSA progression (7.8% vs. 30.0%; p=0.011) and systemic treatment discontinuation (22.5% vs. 45.0%; p=0.037) rates (Table 2).

Table 2. mHSPC metastatic burden and oncological outcome.

| Variable | Total (n=122) | ADT+abiraterone (n=102) | ADT+docetaxel (n=20) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional LNM | 85 (69.7) | 69 (67.6) | 16 (80.0) | 0.272 | |

| Other LNM (M1a) | 53 (43.4) | 44 (43.1) | 9 (45.0) | 0.878 | |

| Bone Metastasis (M1b) | 109 (89.3) | 91 (89.2) | 19 (90.0) | 0.917 | |

| Visceral metastasis (M1c) | 31 (25.4) | 26 (25.5) | 5 (25.0) | 0.963 | |

| Extent of metastasis | 0.726 | ||||

| Low volume | 106 (86.9) | 89 (87.3) | 17 (85.0) | ||

| High volume | 16 (13.1) | 13 (12.7) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| PSA at treatment start (ng/mL) | 180.0 (65.6–610.5) | 185.3 (65.6–638.2) | 100.0 (52.3–578.5) | 0.398 | |

| Testosterone at treatment start (ng/mL) | 3.7 (2.8–4.8) | 4.1 (3.1–5.3) | 3.1 (2.7–4.6) | 0.452 | |

| PSA nadir (ng/mL) | 0.3 (0.0–2.3) | 0.1 (0.0–2.3) | 0.7 (0.6–2.4) | 0.085 | |

| PSA nadir duration (mo) | 5.4 (2.9–8.3) | 5.6 (2.8–8.9) | 4.5 (3.3–8.2) | 0.878 | |

| Systemic treatment discontinuation | 32 (26.2) | 23 (22.5) | 9 (45.0) | 0.037 | |

| Duration of treatment (mo) | 5.5 (3.2–11.1) | 5.4 (3.0–11.5) | 5.5 (4.1–9.4) | 0.742 | |

| PSA progression | 14 (11.5) | 8 (7.8) | 6 (30.0) | 0.011 | |

| PSA at PSA progression (ng/mL) | 25.1 (6.2–44.3) | 25.1 (6.8–50.9) | 29.3 (4.7–52.1) | >0.999 | |

| PSA progression duration (mo) | 10.2 (6.8–13.6) | 11.0 (4.5–13.8) | 10.2 (8.1–13.6) | 0.852 | |

| Radiographical progression | 12 (9.8) | 9 (8.8) | 3 (15.0) | 0.323 | |

| PSA at radiographical progression (ng/mL) | 8.9 (0.3–36.9) | 4.8 (0.2–13.3) | 36.9 (19.1–173.4) | 0.194 | |

| PSA at mCRPC progression (ng/mL) | 36.8 (6.9–145.1) | 14.5 (4.6–105.9) | 37.7 (26.6–167.9) | 0.343 | |

| mCRPC progression | 15 (12.3) | 11 (10.8) | 4 (20.0) | 0.258 | |

| mCRPC progression duration (mo) | 9.9 (5.7–12.2) | 8.4 (5.0–12.5) | 10.6 (9.0–11.4) | 0.571 | |

Values are presented as means±standard deviations, medians (interquartile ranges), or numbers (%), unless otherwise indicated.

mHSPC: metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy, mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, LNM: lymph node metastasis, PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

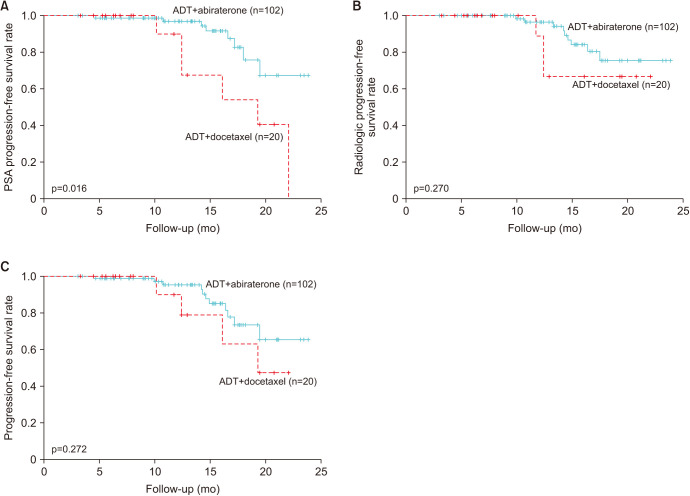

The biochemical PFS rate was significantly longer for patients in the ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group than for those in the ADT+docetaxel group (Fig. 2A). The radiological PFS and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) progression rates were not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 2B, 2C).

Fig. 2. Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) biochemical progression-free survival, (B) radiological progression-free survival, and (C) progression-free survival in the overall population. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy, PSA: prostate-specific antigen.

The median follow-up duration was 10.9 months. No significant difference in the total follow-up duration was observed between the two groups (Table 3). In addition, the adverse event rate was not statistically significant between the two groups (Table 3). Among all adverse events, the occurrence rate of hyperglycemia (1.0% vs. 15.0%; p=0.014), nail toxicity (0.0% vs. 20.0%; p<0.001), and mucositis (0.0% vs. 10.0%; p=0.026) was significantly higher in the ADT+docetaxel group (Table 4).

Table 3. Adverse effects (AEs), follow-up, and survival period.

| Variable | Total (n=122) | ADT+abiraterone (n=102) | ADT+docetaxel (n=20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any AE | 31 (25.4) | 23 (22.5) | 8 (40.0) | 0.101 |

| Any serious AEs | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Any drug-related AEs | 24 (19.7) | 17 (16.7) | 7 (35.0) | 0.071 |

| Grade ≥3 drug-related AEs | 6 (4.9) | 4 (3.9) | 2 (10.0) | 0.255 |

| Treatment discontinuation by AEs | 5 (4.1) | 4 (3.9) | 1 (5.0) | >0.999 |

| AEs leading to death | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Total follow-up period (mo) | 10.9 (6.2–15.9) | 11.1 (6.2–15.9) | 9.7 (5.6–15.3) | 0.564 |

| Survival | 120 (98.4) | 100 (98.0) | 20 (100.0) | >0.999 |

| Survival period (mo) | 10.9 (6.2–15.9) | 11.1 (6.2–15.9) | 9.7 (5.6–15.3) | 0.564 |

Values are presented as medians (interquartile ranges) or numbers (%), unless otherwise indicated.

ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy.

Table 4. Adverse effects occurred in >1% of all patients in this study.

| Variable | Total (n=122) | ADT+abiraterone (n=102) | ADT+docetaxel (n=20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot flash | 12 (9.8) | 10 (9.8) | 2 (10.0) | >0.999 |

| Edema | 6 (4.9) | 3 (2.9) | 3 (15.0) | 0.055 |

| Pain | 6 (4.9) | 5 (4.9) | 1 (5.0) | >0.999 |

| LFT abnormality | 5 (4.1) | 5 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.590 |

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (3.3) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (15.0) | 0.014 |

| Nail toxicity | 4 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Dermatologic disease | 3 (2.5) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (10.0) | 0.070 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (2.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.418 |

| Fatigue | 3 (2.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.418 |

| Anemia | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.302 |

| Constipation | 2 (1.6) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | >0.999 |

| Dyspnea | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.302 |

| Mucositis | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10.0) | 0.026 |

| Nausea | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0.302 |

| Hot flash | 12 (9.8) | 10 (9.8) | 2 (10.0) | >0.999 |

| Edema | 6 (4.9) | 3 (2.9) | 3 (15.0) | 0.055 |

Values are presented as numbers (%), unless otherwise indicated.

ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy, LFT: liver function test.

DISCUSSION

Nearly 10% of patients with prostate cancer had distant metastases at diagnosis, and in this case, the 5-year relative survival rate was much lower than that in patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer [2]. Multiple clinical trials have evaluated the effects of ADT+novel hormonal therapies, including abiraterone, enzalutamide, and apalutamide or docetaxel, on patients with mHSPC [5].

A few clinical studies have compared the efficacy of ADT+docetaxel with that of ADT+abiraterone/prednisone in patients with mHSPC [7,8,9,10]. A network meta-analysis for mHSPC by Marchioni et al [7] showed that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had a statistically significantly lower disease progression rate than ADT+docetaxel; however, no statistically significant difference in OS or adverse effect rate was observed. A retrospective single-center study, including 90 Indian patients with mHSPC, reported that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had a higher serological complete response (50.0% vs. 35.7%) and a lower mCRPC progression rate (11.1% vs. 39.3%) than ADT+docetaxel [8]. However, this study had a short follow-up duration [8]. Another retrospective single-center cohort study involving 121 patients with mHSPC showed that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had a significantly higher PFS (32.0 vs. 18.5 months) than ADT+docetaxel; however, no statistically significant difference in OS was observed between the two treatments [9]. Another retrospective multicenter cohort study, including 196 patients with mHSPC, reported that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had longer PFS 1 (23 vs. 13 months) and PFS 2 (48 vs. 33 months); however, the OS and adverse event rates were not significantly different between the two treatments [10].

Several clinical trials have reported that both ADT+docetaxel and ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had significantly longer OS, PFS, and time to mCRPC progression than ADT alone in patients with mHSPC [5,12,13,14,15,16]. Two single-center and one multicenter retrospective studies that compared ADT+docetaxel with ADT+abiraterone/prednisone reported that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had significantly longer PFS than ADT+docetaxel; however, OS was not significantly different between the two treatments [8,9,10].

In this study, all patients survived during a median follow-up duration of 10.9 months. The biochemical PFS rate was significantly longer in the ADT+abiraterone/prednisone group than in the other group. The radiological PFS and CRPC progression rates were not significantly different between the two groups. The aforementioned clinical trials had a median follow-up duration of 40 to 84 months [5,12,13,14,15,16]. The PSA or radiological PFS of ADT alone was 7 to 15 months, and the median OS was 37 to 71 months [12,13,14,15]. Considering that ADT+abiraterone/prednisone and ADT+docetaxel showed longer OS and PFS than ADT alone, this study had a short follow-up duration for comparing OS and PFS between the two groups [12,13,14,15].

The ratio of PSA decrease >50%, used as clinical response measurement, was demonstrated to be associated with longer OS in patients with nonmetastatic CRPC in the post hoc analysis of the PROSPER randomized clinical trials [17,18]. In this study, it was similar with that in other retrospective studies comparing ADT+abiraterone/prednisone with ADT+docetaxel (93.4%–97.3% vs. 98.5%) [8,9,10]. In a retrospective study involving patients with clinically localized prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy in Korea, the prevalence of distant metastasis was lower than that observed in Western countries; however, patients with distant metastasis died earlier than those in Western countries [19]. Additionally, a retrospective cohort study that compared the pathological aggressiveness of clinically localized prostate cancer in Korea with that in Western countries showed that the incidence of prostate cancer with a higher grade or advanced stage was higher in Korean men [11]. In this study, age and the ratio of high-volume disease were similar to those in other retrospective studies; however, the ratio of International Society of Urologic Pathologists grade 4 or 5 tumors was higher in this study than in other retrospective studies (95.0% vs. 66.7%–80.1%) [8,9,10]. The difference in aggressiveness caused by ethnics may contribute to the different efficacies [11,19].

The adverse events rate was associated with treatment discontinuation, interruption, or dose reduction [14,15]. James et al [14] reported that 13.3% discontinued ADT+docetaxel therapy, whereas Fizazi et al [15] reported that 15.6% of the patients discontinued ADT+abiraterone/prednisone because of adverse events. The rate of systemic treatment discontinuation was 18.8% and that of ADT+docetaxel group was slightly higher (22.2% vs. 17.4%) in this study. The rates of any adverse events and any drug-related adverse events were not significantly different between the two groups. A network meta-analysis reported no statistically significant difference in the rate of adverse events between the ADT+abiraterone/prednisone and ADT+docetaxel groups [7]. Sydes et al [20] also reported that the rate of adverse events was similar between the two groups. However, the adverse event rates in the ADT+docetaxel (40% vs. 100%) and ADT+abiraterone/prednisone (23% vs. 99%) groups were lower than those in the study by Sydes et al [20]. Furthermore, the rates of grade ≥3 adverse events in the ADT+docetaxel (10% vs. 50%) and ADT+abiraterone/prednisone (3.9% vs. 48%) groups were lower [20]. The short follow-up period (10.9 months vs. 48 months) and the small sample size (122 vs. 566) in this study may contribute to these differences [20].

Adverse events caused by docetaxel included fatigue, anemia, alopecia, and nail toxicity [5,13,14,21,22]. Otherwise, abiraterone may cause adverse events, such as hypertension, hypokalemia, hot flashes, back pain, arthralgia, hepatotoxicity, and cardiac disorders, including atrial fibrillation [5,12,23]. Among all adverse events, nail toxicity occurred significantly more frequently in the ADT+docetaxel group in this study. This adverse event is an acute side effect caused by docetaxel chemotherapy [24,25,26]. Among abiraterone-induced adverse events, the occurrence of hepatotoxicity was slightly higher in the ADT+abiraterone group; however, the difference was not statistically significant.

The study strength is that this is the first study to compare ADT+docetaxel with ADT+abiraterone/prednisone in patients with mHSPC whose data were collected from several institutions in Korea. We thoroughly described the study’s early nature and clearly emphasize on the short-term oncologic outcomes and safety profiles as the main focus before the data is mature enough to produce the OS result.

However, this study has some limitations. First, the follow-up period was short (median, 10.9 months). Second, the study population was small (n=122). To solve these weak points, a study involving a larger cohort with a longer follow-up period including OS and PFS 2 is necessary. Third, this study could contain some errors because of its retrospective design. Finally, this study was not a double-blinded randomized study. Leith et al [27] reported several reasons for choosing ADT+docetaxel to treat mHSPC. Among these reasons, both younger age and good performance status were reported to be associated with longer OS [28,29]. In addition, the study compared the outcomes of ADT+docetaxel between older and younger patients with mHSPC and demonstrated that older patients had increased ratio of grade 3–5 adverse events than younger patients [30]. Considering these points, the limitations of our study may cause bias about treatment outcomes or adverse events.

CONCLUSIONS

ADT+abiraterone/prednisone had lower PSA progression and systemic treatment discontinuation rates than ADT+docetaxel. For a better conclusion, further studies involving larger, double-blinded randomized trials with extended follow-up periods are necessary.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding: None.

- Research conception and design: SHC.

- Data curation: all authors.

- Formal analysis: DJP, SHC.

- Funding acquisition: CWJ, CK.

- Investigation: JYP, SHL.

- Methodology: SHC, CK.

- Project administration: JYJ.

- Resources: CWJ, SHC.

- Software: DJP, SHC.

- Supervision: CWJ, TGK.

- Validation: SSJ, SP.

- Visualization: DJP, SHC.

- Writing – original draft: DJP, SHC.

- Writing – review and editing: DJP, SHC.

Data Sharing Statement

The data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found via https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.230104.

Demographic characteristics and past medical history of the study population

Baseline cancer status of the study population

Initial laboratory tests

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang MJ, Jung KW, Bang SH, Choi SH, Park EH, Yun EH, et al. Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2020. Cancer Res Treat. 2023;55:385–399. doi: 10.4143/crt.2023.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korea Central Cancer Registry. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2019. Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessel A, Kohli M, Swami U. Current management of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;28:100384. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandel P, Hoeh B, Wenzel M, Preisser F, Tian Z, Tilki D, et al. Triplet or doublet therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol Focus. 2023;9:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2022.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchioni M, Di Nicola M, Primiceri G, Novara G, Castellan P, Paul AK, et al. New antiandrogen compounds compared to docetaxel for metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer: results from a network meta-analysis. J Urol. 2020;203:751–759. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta A, Hussain SM, Sonthwal N, Chaturvedi H. Addition of docetaxel or abiraterone to androgen deprivation therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in Indian population. J Cancer Res Ther. 2021;17:389–392. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_342_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briones J, Khan M, Sidhu AK, Zhang L, Smoragiewicz M, Emmenegger U. Population-based study of docetaxel or abiraterone effectiveness and predictive markers of progression free survival in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:658331. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.658331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsaur I, Heidegger I, Bektic J, Kafka M, van den Bergh RCN, Hunting JCB, et al. EAU-YAU Prostate Cancer Working Party. A real-world comparison of docetaxel versus abiraterone acetate for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Cancer Med. 2021;10:6354–6364. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong IG, Dajani D, Verghese M, Hwang J, Cho YM, Hong JH, et al. Differences in the aggressiveness of prostate cancer among Korean, Caucasian, and African American men: a retrospective cohort study of radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:3.e9–3.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gravis G, Boher JM, Joly F, Soulié M, Albiges L, Priou F, et al. GETUG. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) plus docetaxel versus ADT alone in metastatic non castrate prostate cancer: impact of metastatic burden and long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase 3 GETUG-AFU15 trial. Eur Urol. 2016;70:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyriakopoulos CE, Chen YH, Carducci MA, Liu G, Jarrard DF, Hahn NM, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: long-term survival analysis of the randomized phase III E3805 CHAARTED trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1080–1087. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, Spears MR, et al. STAMPEDE Investigators. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1163–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:686–700. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, et al. STAMPEDE Investigators. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:338–351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scher HI, Morris MJ, Basch E, Heller G. End points and outcomes in castration-resistant prostate cancer: from clinical trials to clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3695–3704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain M, Sternberg CN, Efstathiou E, Fizazi K, Shen Q, Lin X, et al. Nadir prostate-specific antigen as an independent predictor of survival outcomes: a post hoc analysis of the PROSPER randomized clinical trial. J Urol. 2023;209:532–539. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh J, Jung JH, Jeong CW, Lee SE, Lee E, Ku JH, et al. Long-term oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy in clinically localized prostate cancer: 10-year follow-up in Korea. Investig Clin Urol. 2020;61:269–276. doi: 10.4111/icu.2020.61.3.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sydes MR, Spears MR, Mason MD, Clarke NW, Dearnaley DP, de Bono JS, et al. STAMPEDE Investigators. Adding abiraterone or docetaxel to long-term hormone therapy for prostate cancer: directly randomised data from the STAMPEDE multi-arm, multi-stage platform protocol. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1235–1248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, Oudard S, Priou F, Esterni B, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capriotti K, Capriotti JA, Lessin S, Wu S, Goldfarb S, Belum VR, et al. The risk of nail changes with taxane chemotherapy: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:842–845. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP, Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, et al. ARCHES: a randomized, phase III study of androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2974–2986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho MY, Mackey JR. Presentation and management of docetaxel-related adverse effects in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:253–259. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S40601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hood AF. Cutaneous side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Med Clin North Am. 1986;70:187–209. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30976-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seguin C, Kovacevich N, Voutsadakis IA. Docetaxel-associated myalgia-arthralgia syndrome in patients with breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2017;9:39–44. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S124646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leith A, Ribbands A, Kim J, Clayton E, Gillespie-Akar L, Yang L, et al. Impact of next-generation hormonal agents on treatment patterns among patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: a real-world study from the United States, five European countries and Japan. BMC Urol. 2022;22:33. doi: 10.1186/s12894-022-00979-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernard B, Burnett C, Sweeney CJ, Rider JR, Sridhar SS. Impact of age at diagnosis of de novo metastatic prostate cancer on survival. Cancer. 2020;126:986–993. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyazawa Y, Sekine Y, Arai S, Oka D, Nakayama H, Syuto T, et al. Prognostic factors in hormone-sensitive prostate cancer patients treated with combined androgen blockade: a consecutive 15-year study at a single Japanese institute. In Vivo. 2021;35:373–384. doi: 10.21873/invivo.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lage DE, Michaelson MD, Lee RJ, Greer JA, Temel JS, Sweeney CJ. Outcomes of older men receiving docetaxel for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021;24:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/s41391-021-00389-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Demographic characteristics and past medical history of the study population

Baseline cancer status of the study population

Initial laboratory tests

Data Availability Statement

The data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data also forms part of an ongoing study.