Abstract

Objective:

Aspects of the written application, interview and ranking may negatively impact recruitment of underrepresented in medicine (URiM) applicants. Our objectives were to explore knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pediatric faculty who assess potential trainees and how diversity impacts these assessments.

Methods:

We performed qualitative interviews of 20 geographically diverse faculty at large pediatric residencies and fellowships. We analyzed data using the constant comparative method to develop themes.

Results:

Four main themes emerged.

1) Screening applications and offering interviews: A standardized process flawed by subjectivity. Participants screened applications for clinical skills, research activities, or unique attributes and assigned scores based on program values. Strategies to mitigate bias included a holistic approach to review and assigning lesser weight to board scores.

2) Interviews: Personality matters. Participants used interviews to obtain additional information about applicants and to assess personality. Strategies to decrease bias included the use of behavior-based questions and blinding interviewers to the application.

3) Determination of the rank list: The rise and fall of applicants. Initial rank lists were informed by local scoring systems. Many participants altered lists through subjective inputs from the selection committee. Mitigation strategies included intentional discussion of bias and intentional changes to promote diversity.

4) The recruitment process: Values, challenges, and strategies to promote diversity. Most programs enacted bias training and purposeful URiM recruitment.

Conclusions:

We describe ways in which bias infiltrates recruitment and strategies to promote diversity. Many strategies are variably implemented and the impact on workforce diversity in pediatric training programs remains unknown.

Keywords: bias, diversity, recruitment, trainees

Background

Inequities in medical education in the form of discrimination based on gender, race and ethnicity1 contribute to a lack of diversity among medical trainees. This is particularly true for Black, Hispanic, and Latinx physicians, who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) relative to the greater US population.2 Improving recruitment of URiM candidates is a goal of many institutions. Over the last decade, the proportion of URiM pediatric residents has remained stable, however the proportion of URiM pediatric fellows has significantly decreased.3 This may, in part, be related to unconscious bias indicating implicit white preference among selection committees.4

Program directors (PDs), especially from competitive specialties, review large numbers of applications annually, seeking successful candidates. Applicant selection often has three parts. First, review of the written application is used to determine which applicants to interview. Then as interviews are limited in number, PDs often choose between candidates of similar caliber; these decisions can be difficult and subjective.5,6 Finally, information from the written application and interview is used to rank applicants for the Match. Program directors and selection committees can be susceptible to cognitive errors, which are exacerbated by organizational dysfunction. For example, committees may feel overwhelmed and rush to sort through a large volume of applications to quickly invite competitive candidates making them more prone to errors such as assumptions and premature ranking.7

The applicant selection process can detrimentally impact URiM applicants. Due to structural racism and inherent biases, URiM medical students have poorer standardized test scores,8 clerkship grades and performance reports,9 letters of recommendations (LORs),10 and are less likely to have honor society memberships11 or research opportunities12 as compared to their non-URiM peers. The negative impact can lead to fewer URiM candidates being selected to interview at training programs.13–15 Interviews, which often incorporate subjective assessments of applicants, are reported as a heavily weighted factor in applicant assessment and ranking.5,16 Finally, ranking of applicants can incorporate subjectivity and bias. It is unclear how often selection committees receive training on how to evaluate applicants, what applicant credentials are required versus preferred, or if faculty receive feedback on their decisions with respect to potential biases.7 To improve diversity, organizations such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommend holistic review, in which graduate institutions consider applicants’ experiences, attributes and academic metrics as well as the value an applicant might contribute to the learning environment. Holistic review encourages program leaders to consider the whole person rather than relying heavily on any one factor.17,18 However, it is unknown if and how program directors and recruitment leaders in Pediatrics are implementing strategies of holistic review to improve diversity in recruitment efforts.

Exploring decision-making around trainee selection and factors that can mitigate bias is an essential step in reducing disparity in the selection of trainees. Therefore, our objectives were to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of faculty who interview and assess applicants to pediatric training programs and to understand how diversity impact these assessments.

Methods

Using a qualitative approach, we conducted semi-structured, one-on-one interviews of PDs, associate PDs and faculty involved in recruitment to understand the process of screening and selecting applicants. We targeted competitive specialties where PDs choose from large applicant pools.19 Participants were purposively recruited via email and snowball sampling to assure wide geographic representation, and adequate capture of program leaders in pediatric residencies and four competitive pediatric subspecialties.20 Participants were compensated with a $25 gift card.

One investigator (DC) with experience in qualitative interviewing conducted virtual interviews from January to September, 2022. The research team developed and iteratively modified an interview guide (Table 1). Questions focused on understanding strategies used to screen, interview and rank applicants and explore known biases in applicant materials. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Yale University’s institutional review board considered the study exempt.

Table 1.

Final Interview Guide

| • How do you assess an applicant’s written application? |

| • What roles do different parts of the ERAS* application play in your initial assessment of an applicant? |

| ○ What parts of the written application are most important in helping you assess an applicant? |

| • If you have 3 interview slots and 5 applicants, what factors do you consider when choosing which 3 applicants to interview? |

| • What is your approach to interviewing an applicant? |

| ○ Tell me about how you evaluate applicants that you interview. |

| • Tell me about how you determine your rank list. |

| • How does an applicant’s race and ethnicity factor into the selection process for your program? |

| • In your program, are there any approaches or strategies to improve diversity or mitigate bias in the selection process? |

Electronic Residency Application Service.

Analysis

To ensure reliability of the qualitative process, five researchers experienced in qualitative analysis coded the data using the constant comparative method of grounded theory.20–22 In line with the constant comparative method, researchers performed open, axial and selective coding. First, they independently reviewed each transcript and applied codes to categorize portions of the data, as well as memos to highlight areas for discussion.22 A developing code list with definitions and guidelines for code application, was used to analyze subsequent transcripts. When discrepancies arose, researchers reviewed text segments and engaged in discussion to attain consensus. Codes were iteratively expanded and revised as they were applied to incoming data until a final code structure emerged.22 One researcher (MLL) reviewed previously coded transcripts and reapplied the final code structure. Finally, when the coding process was complete, codes were clustered into categories then themes. Qualitative software (Dedoose version 9.0.54) facilitated data organization and management. To optimize dependability, we maintained an audit trail and members of the research team had varying involvement in graduate medical education and included members who were underrepresented in medicine. To optimize credibility, data collection and analysis continued past the point of theoretical sufficiency.23

Results

We interviewed 20 of 26 participants recruited from pediatric residency and fellowship programs (Table 2). Six participants deferred participation. Participants used varying definitions of URiM status. Many cited definitions from national groups such as the AAMC, some used race or ethnicity, and others incorporated broader definitions or vague descriptions such as “it’s someone who doesn’t necessarily look like me”. Participants also discussed diversity beyond race and ethnicity, highlighting gender identity, religion, sexual identity, geographic location, and the influence of primary language. They noted that the ability to identify URiM candidates relied on applicant self-identification, limited demographic categories, and the impact of photographs and visual stereotypes.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Specialty, N (%) | |

| General Pediatrics | 5 (25) |

| Cardiology | 3 (15) |

| Critical Care Medicine | 4 (20) |

| Emergency Medicine | 4 (20) |

| Neonatology | 4 (20) |

| Region, N (%) | |

| Northeast | 8 (40) |

| Midwest | 6 (30) |

| South | 3 (15) |

| West | 3 (15) |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Female | 12 (60%) |

| Male | 8 (40%) |

| Current or Past Program Director or Associate Program Director | 18 (90%) |

| Mean Years Involved in Recruitment, Standard Deviation | 11.5 (8.8) |

Four themes emerged from our data: 1) Screening applications and offering interviews: A standardized process flawed by subjectivity, 2) Interviews: Personality matters, 3) Determination of the rank list: The rise and fall of applicants, and 4) The recruitment process: Values, challenges, and strategies to promote diversity. Representative quotes from each theme are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Themes and Representative Quotes

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Screening applications and offering interviews: A standardized process flawed by subjectivity | |

| • Subjectivity in interview invitation decisions | A hundred applications for two spots is pretty competitive. And so the first cuts, so to speak, is really to get down to 30–40 applicants. So with a hundred, it’s about cutting 60%, essentially. Sixty to seventy percent essentially. And so that’s the hard thing. And that’s where it comes in with bias and stuff, because there’s not a great way to do that other than the application. And as objective as we try to make it, it’s really hard because there’s not really a set objective data that says that if an applicant has X, Y, or Z, then they’re going to be successful. |

| • Differential weights to sections of the application | I think that having the way that the composite score has been developed for us, that relegates the weight of the test score and the med school grades to a very small proportion of the overall score, was the approach that we chose to take to try and mitigate that implicit bias. |

| • Coded application language | We all just have this language we use. It’s like if someone’s great, you give them the highest level of recommendation, outstanding, just all of these accolades you try and fill in there. And then if you have someone who’s not as great, you’re like, “Really improved over the course of residency, was eager to learn, did well,” so just like less enthusiastic qualifiers is how we read between the lines of like, “Oh, they don’t actually think this person’s amazing because if they thought they were amazing, they would say they were amazing. They think they’re okay.” |

| • Variable definitions of applicant red flags | So what are some red flags? They’re almost anything. Somebody who emails and communicates too often. Like, that’s a red flag. Somebody who’s too desperate and pushing too hard to try to get into the program. That’s an issue. People who, I’m unhappy to say it, but people had to repeat a year of medical school. I mean, that’s not a red flag. That’s just a fact, right? People fail their steps. People who had to take a leave for medical reasons. Even though that could be something as simple as, “I had pneumonia.” More often than not, it’s a mental health issue, and those usually get worse during residency instead of better. And I know I’m not supposed to pay attention to all those things, but you can’t help but notice there’s something, even though I don’t know the details, if somebody’s gone for a month for whatever reason, I’m like, “Something funny.” |

| • Perception of training programs and their clinical experiences | Residency quality...it talks about is this a university based program with a lot of exposure or is this a hospital based program that maybe doesn’t have all the resources kind of thing and that metric in particular I think we kind of couch a little bit on just because we wanna, it’s both an exposure thing, but it can also bias us, right? Because like, some applicants aren’t necessarily gonna end up in university based things, so they can’t really be held accountable for the fact that maybe they don’t have the best exposure. |

| Interviews: Personality matters | |

| • Conversational interviews focused on shared interests | I like that idea of structured questions ’cause I think it takes bias out of it because if you just talk about your shared experiences, then you’re going to really, you might miss out on people who you know you might, downgrade folks who don’t have a shared experience as don’t have the share similar shared experience with you and stuff. |

| • Differences in perception of applicant personality | There’s some interactions that people have that are very different from other people’s interactions. And so sort of weighing those interactions...we get currently Zoom meetings for three and a half hours to sort of try to figure out somebody’s personality and we have a big stack of paper. And so I do sort of personally take any sort of flags that anybody has in that time period as pretty concerning. If somebody can’t cover up something over a three-hour interaction, then how often is that going to come up in real life? |

| • Interpretation of communication and interpersonal skills | Academically everybody’s going to have strong applications, but it’s kind of their interpersonal skills that we’re looking for. So any feedback that the fellows can give is really helpful and they are part of our selection meeting. And that also goes for... our fellowship coordinator, who does a lot of the, she is the person probably who interacts the most with the candidates and for 90% of them, she has nothing to say. And then she’ll definitely highlight a couple that she thought worked with her incredibly well or incredibly poorly. And it really does mean a lot to us when we hear that. I pay clear attention to...their social skills, because a pediatrician has to be able to talk to 2-year olds, to 8-year olds, to teenagers, to parents, to grandparents. You got to be smooth in conversation. And there are people who aren’t. And that, to me, is another red flag. So if there’s a 265 on their Steps, but they cannot make eye contact, they can’t pay attention, they seem easily flustered, then the parents aren’t going to trust them, the kids aren’t going to trust them. |

| • Burden of travel for in-person interviews | There’s some real socioeconomic barriers to the interview process. I mean, there’s socioeconomic barriers all throughout medicine, but the interview process is really one of them... it costs me a lot of money and if I get the interview and I fly out there and I get a hotel room for the night and all of these things, it’s prohibitive. It’s completely prohibitive. I was very fortunate that I was able to go on every interview I was offered, and that cost a ton of money. But lot of people don’t have that privilege. They don’t have that, that good fortune. |

| Determination of the rank list: The rise and fall of applicants | |

| • Applicant movement based on subjective feelings | We have them write in feedback, but that’s really the first time that they’re like, “Oh yeah, that person was a total weirdo or something, or oh, we really loved her.” So then sometimes we move people around based on that. I see her point about not having people move too much because we’re trying to use this fairer system. But there has been some movement with people, absolutely. Not the way it used to be, where somebody would be number three and then they’d be number 40. We were wondering if that was fair. Because it was a lot of, “I liked that.” It was just a little bit too much, we didn’t think it was fair. |

| • Variation in methods to create initial rank list | We’ll have the morning of interviews. Then, everyone who interviewed meets after and we develop this running rank list. So people weigh in and then we plug people in as we go, and we always make changes at the end, but we plug people in as we go. |

| • Group selection committee decisions versus Program Director only decisions | I cut out everybody else who could possibly be biased, and I just did it myself. So, that’s one process. That’s probably the big one, honestly. |

| • Role of faculty sponsorship of applicants | If someone I trust is like, “This person is fabulous,” that means the world to me. |

| The recruitment process: Values, challenges, and diversity | |

| • Diverse workforce reflective of patients served | One important piece of that is starting with the people who are providing the healthcare and the experiences that those people bring into their perspective. So it’s very important to me that we actively recruit people from all backgrounds, and in particular underrepresented in medicine backgrounds, because our patient population comes from a racial pool that is part of the underrepresented in medicine group. |

| • Geographic location | We are very racially divided city. That has been baked into the history of Saint Louis since it was founded, and there are major problems with the way that the health care system integrates within the community. |

| • Data driven reflection | I think the data really show us how we’re doing. And so by reviewing that, it’s actually really informative for me to go through and with the process and identify any red flags...I also look at other metrics. So how did we do in terms of underrepresented medicine and BIPOC etcetera, in the different categories? Did we match better in this category or not? And then try to think about how we can do better to recruit. |

Screening Applications and Offering Interviews: A Standardized Process Flawed by Subjectivity

Many participants described similar processes for screening large volumes of applicants and subjective methods to decide who to interview. While participants involved in residency and fellowship recruitment described using similar processes to screen applicants, residency participants described screening larger applicant pools and thus needing efficient strategies to help determine which applicants to interview. For example, many described using the medical student performance evaluation (MSPE) to assess “how good the student was” or to assess an applicant’s performance during his/her pediatric rotation. Participants described assessing written applications for information about clinical skills, research activities, academic record, leadership activities and volunteerism, as well as more holistic attributes such as initiative, resilience, and “stand out” attributes. Participants assigned weights to these areas based on their program values. Almost all participants mentioned looking for “red flags”. These included failures in the academic record or on tests, evidence of poor communication or lack of professionalism described in the application or during interactions during the application process, poorly written personal statements, and concerning LORs. These red flags were used to screen out applicants, as this participant describes:

“My advice to all program directors is pay attention to everything that you can even pretend might be a red flag. Especially when I have tons of applicants. Why would I take somebody with a red flag, if they’re equivalent to somebody else who doesn’t have a red flag?”

Many aspects of LORs were mentioned by participants as influential, including their length and quality, personal knowledge of the writers, and “coded language” used within LORs. Coded language was reported as the use of weaker or stronger adjectives when describing applicants. One PD used internal comparisons, assessing applicants from the same institution against one another to get a better sense of their ranking. External factors including Graduate Medical Education (GME) requirements on visa eligibility and required board pass rates for a program also impacted applicant screening. While many participants used a system to screen applicants based on the written application, methods varied from gestalt determinations regarding their desire to interview to use of scoring tools with anchored scales. This led to the creation of tiers of candidates – those offered an interview, those declined, and an indeterminate category.

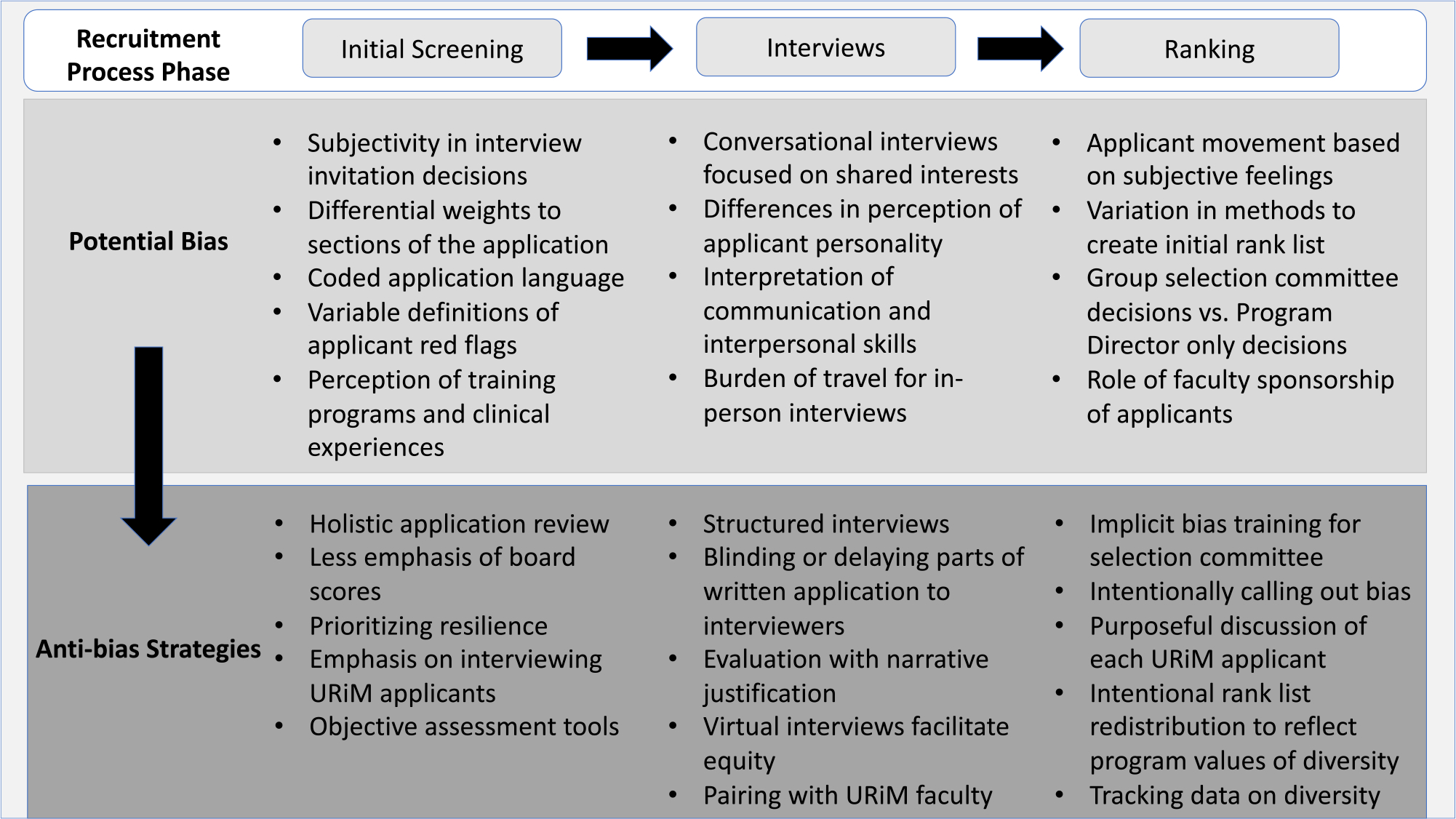

Bias and subjectivity factored into applicant screening in several ways as participants tried to perceive the potential fit of an applicant within their program (Fig. 1). Many described how an applicant’s perceived clinical exposure, impacted by the reputation of their training institution, influenced the interview decision. Participants also commonly expressed that they were more likely to interview applicants from the same geographic area.

Figure 1.

Areas of potential bias and anti-bias strategies expressed in each part of the selection process.

To promote diversity, equity and inclusion, participants utilized several strategies including a holistic review process. Although test scores were sometimes used to screen out applicants, many participants described assigning a lesser weight to this aspect of the application. Some participants performed purposeful, thorough reviews of written materials including screening for positive behaviors not typically assessed such as resilience. Others added points to scoring tools or intentionally offered interviews to URiM applicants. One PD also suggested that LORs become standardized.

Interviews: Personality Matters

Interviews were largely perceived as a bidirectional tool to explore personality alignment between the applicant and program. Participants chose select faculty members to interview, allowed all faculty to interview, or purposefully prohibited individuals who were perceived as biased. Participants used interviews to obtain additional information such as degree of commitment to activities, explanations for red flags, career goals, insight into the field, and degree of interest in their program. An applicant’s personality, communication and interpersonal skills were considered to significantly alter perceptions about an applicant, highlighted in this comment:

“This person looked good on paper, but it’s just if they don’t ask us questions about our program and they don’t seem super enthusiastic about it, if they’re not able to think about what they would do during fellowship outside of the clinical experience, it’s always something that we’re just like, I don’t know. I can’t picture what this person will do and what they will bring. So they’re ranked lower, and yeah, if you just really can’t even fill 30 minutes having a conversation with somebody. they go to the bottom of the list.”

Recognizing that interviews and evaluations of personality fit could be biased, participants described various mitigation strategies (Fig. 1). Some blinded faculty to parts of the application such as test scores or LORs. Others provided written materials after the interview to reduce pre-formed biases when evaluating an applicant’s interview performance. Additional strategies included the use of behavior-based questions instead of conversational interviews. Some programs intentionally paired applicants with URiM faculty members for interviews as another recruitment strategy. Finally, some PDs described the use of scoring tools with or without narrative justifications or verbal debriefing sessions to gather information from interviewers.

Determination of the Rank List: The Rise and Fall of Applicants

PDs created their initial rank list in a variety of ways such as tabulating scores from faculty evaluations after the final interview or ranking applicants in real time throughout the season. As the list was created, parts of the evaluation process, such as the interview or personal communications, were weighed differently by different programs. Personal communication from the applicant or sponsors, people speaking on the applicant’s behalf, could impact an applicant’s position on the rank list. Some PDs reached out to close colleagues or the PD at an applicant’s current institution for supplementary information.

An applicant’s rank list position was susceptible to movement based on subjective feelings and institutional values. Many participants described group meetings to determine the final list, while other PDs took sole responsibility for the results. Group discussions led to the movement of applicants up or down the rank list for a variety of reasons including perceived fit, interactions with faculty, red flags identified during interviews or through conversations with colleagues. While most programs sought out and valued the feedback of faculty and trainees, the sway of subjective feedback could vary as is illustrated by these two contrasting quotes:

“I pay less attention to their thoughts of the interview than I do to the whole application package. Like they may come in and say, “This person was terrible. I. blah, blah, blah.” I’ll take that in mind, but if they look great on paper. I’ll probably still rank them reasonably well.”

“Sometimes the way the fellows interacted with somebody, they’ve been so adamant that it was such an awkward, terrible interaction that we have actually taken people from the top five and moved them way down because they’ve just been like, “Hey, that’s great that he looks great on paper. That’s great that he was able to talk well in an interview, but not a normal person with peers”.

Several participants raised concerns about how bias could influence the rank list and strategies to regulate these concerns (Fig. 1). Many PDs described instances where they recognized bias among certain faculty members. Participants created selection committees, increased the number and breadth of faculty members involved in selection, or eliminated faculty members from selection to lessen the impact of any one individual’s biases. In discussions about the rank list, some PDs or selection committees were thoughtful about calling out bias and asked for clarification about comments or used diversity officers for this purpose. Some purposefully discussed each URiM applicant and critically reviewed their position on the list. Others intentionally assessed the diversity of applicants on their list and made changes to promote a diverse class.

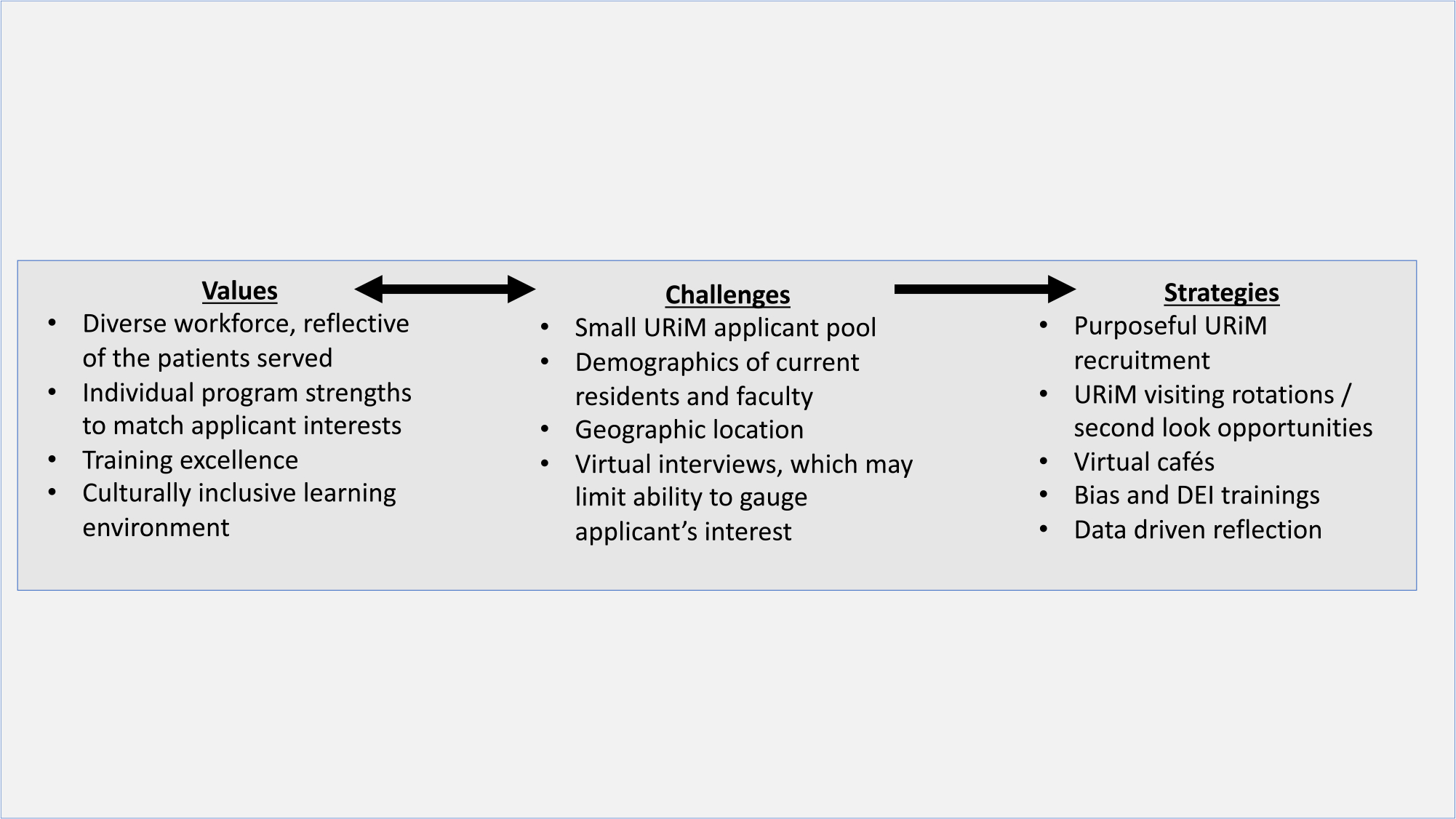

The Recruitment Process: Values, Challenges, and Diversity

Figure 2 highlights participants’ feelings about the recruitment process. Most participants described the value of a diverse work force, one that met the needs of the community served by their program. However, some felt that recruiting a diverse class was difficult given that all programs desired more URiM applicants despite a small URiM applicant pool. While participants wanted to match the strength and values of their program to an applicant’s needs, some were concerned with the perception of their program. Specifically, participants were concerned with the perceived strength of their research program compared to other hospitals, the reputation of their geographic location, and how the demographic makeup of their department impacted recruiting.

Figure 2.

The recruitment process: values, challenges and global strategies to promote diversity in pediatric training programs.

Many participants commented on the impact of virtual interviews. Virtual interviews eliminated travel costs which theoretically allowed applicants to traverse larger geographic distances and lessen the impact of applicants balancing interviews with work and home responsibilities. However, participants also expressed concern that it was harder to gauge an applicant’s genuine interest in a program where there is unclear geographic pull and harder to virtually showcase the benefits of a given area. Some programs leveraged the virtual forum for virtual cafes or informal meetings as a tool to highlight diversity. Second look visits and targeted outreach to URiM applicants were also used to improve success in recruitment.

Participants recognized that recruitment had many potential pitfalls for bias. Many departments or participants instituted diversity training or other initiatives to better recognize bias and educate faculty. Others obtained financial support for recruitment initiatives or away electives to promote diversity. Tracking data was described by some participants as a tool to balance recruitment on multiple demographic fronts including gender and race, serving as a check to assess if changes made to promote diversity recruitment prove efficacious over time.

Discussion

Our study is the first to qualitatively describe how program leaders navigate efforts to improve diversity as they screen pediatric fellowship and residency applicants, offer and perform interviews and determine rank lists. While participants described some standard procedures and strategies to improve diversity within their programs, subjectivity allowed the potential for bias to have a role throughout recruitment process. The effectiveness of these strategies remains unknown, especially when balanced against institutional, departmental and geographic factors that simultaneously influence an applicant’s decisions.

It may first be necessary to have unifying, yet flexible definitions of diversity and URiM status. The AAMC defines URiM as those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the profession relative to their numbers in the general population.24 This allows for the including and removing of groups on the basis of changing demographics of society and the profession. Defining URiM locally is critical to examining the impact of strategies that promote diversity. However, ultimately, identification of URiM candidates may still be a challenge as it relies on self-identification.

While some interventions designed to increase medical student diversity have been identified,17,25 less is known about diversity at the GME level, particularly among competitive specialties. Given the decline in the proportion of URiM trainees in pediatric fellowships3 and the high-stakes selection process in these fields, proactive interventions are required to increase the number of URiM physicians. Prior studies have examined factors important to PDs when selecting applicants for interview. Similar to our study, LORs, commitment to the specialty, research, leadership, geography and reputation of an applicant’s training program were perceived as important in the initial screening process.5,6 While algorithms exist to screen written applications for these factors, use of these tools has not increased diversity in selection of candidates, likely due to biases found within chosen factors and an inability to target characteristics that are associated with diversity.26–29 On the other hand, integration of holistic review strategies such as purposefully adding points for URiM applicants or applying principles of holistic review to institutional scoring rubrics improved diversity in multiple studies.17,18 Future consideration may also be give to the use of equity frameworks to address individual, interpersonal and institutional bias and to implement a more balanced holistic review at each stage of the application, interview and ranking process.30 To further understand the use of LORs, stakeholders in our study discussed how coded language, personal knowledge of letter writers and LOR quality were used to evaluate applications. While many stakeholders recognized the importance of diversifying their trainee workforce, reliance on factors such as the personal knowledge of letter writers and the reputation of an applicant’s training program, may conversely lead to increased bias and decrease recruitment of URiM applicants.31 One strategy is to standardize LORs, however this may not improve diversity without writer training and thoughtful inclusion of holistic components.32

Demographic differences seen in standardized testing can negatively impact URiM applicants.14 Many participants discussed deprioritizing test scores. As the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) step 1 has transitioned to a pass/fail grading system, PDs should consider evaluating all USMLE scores in a similar fashion until the remaining Steps move away from numeric scores.33 This strategy may improve acceptance of URiM applicants as the use of cut-off values from standardized tests has been associated with racial bias.8,14 Prescribing lesser value to scores may be one avenue to decrease bias, however other ways to assess applicants more holistically are necessary. Tools that favor holistic review, a flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes and academics, may attenuate the impact of racial biases in the decision to offer interviews.34 Holistic screening processes have often led to significant increases in URiM students being interviewed and matching in several training programs.18,30,34–37 Blinding faculty to written applications and self-identification also led to URiM applicants receiving higher rankings than when scored by non-blinded faculty.38

Our participants described using the interview to explore written applications, assess interpersonal skills and determine applicant fit within their programs. One study at a pediatric program found that interview scores were the most important variable for ranking.16 However, recognizing that interviewers tend to rank individuals with similar personalities more highly and that the term “fit” may reflect personal comfort used to justify these decisions,7,39 participants described strategies such as the use of behavioral-based interviews and blinding faculty to aspects of the written application prior to the interview to potentially reduce biases in applicant assessment.16,40 Examination of the impact of such strategies on the reduction of bias in applicant selection may facilitate change in the interview process.

In pediatrics, a significant increase in the proportion of URiM interns occurred at one training institution after implementation of an equity framework, but the impact of each component of this framework is unknown.30 Similar to the strategies noted by our participants, many of these approaches are feasible, but tracking data and analyzing desired outcomes will be an imperative next step.41 Much of the current published data focuses on medical school admissions, and those that have focused on race and ethnicity often produced mixed results.17,42 Thus, despite one’s best efforts and implementation of multiple strategies, recruiting diverse candidates may be elusive. As some of our participants noted, simultaneous efforts need to occur outside of an individual’s program at the organizational level or within a community. Further, while holistic review may produce a more diverse workforce, it remains to be determined which aspects or best practices of the holistic review process impact workforce diversity most strongly and most reliably.41 Multi-center studies are needed to evaluate the impact of holistic review and anti-bias strategies on workforce diversity and ultimately on patient outcomes.

Limitations:

Our study has limitations. First, due to the recruitment of 20 program leaders of large, competitive subspecialty programs in pediatrics, our findings may not be generalizable to smaller programs or all specialties and provide insufficient insight into whether biases in the recruitment process impact decision-making in the selection of applicants. However, we made efforts to incorporate perspectives from a national and geographically diverse group and conducted interviews past the point of theoretical saturation. Second, our data comprise rich narratives which represent perceptions of program leaders, not direct observations of recruitment and anti-bias practices. Third, our findings were hypothesis generating and while participants discussed numerous strategies used locally to decrease bias in the recruitment process, we did not study the impact of these strategies. Finally, participants may have been impacted by a social desirability bias and modified their answers to present themselves in a more favorable light. Incorporation of “negative cases,” or in this case, those with less positive perceptions about incorporating anti-bias strategies in the recruitment process, may have decreased potential bias in the selection of participants. To further minimize this bias, a research assistant ensured confidentiality and emphasized the need for honesty in participant responses.

Conclusion

Though program leaders use many common procedures in the recruitment and selection of pediatric trainees, the potential for bias remains in each step. We report many variably implemented strategies employed to mitigate bias. However, the impact of these strategies on workforce diversity remains unknown. Multi-site collaboration to study the impact of holistic review and anti-bias strategies is needed to drive change.

What’s New.

Pediatric residency and fellowship program leaders identified areas of potential bias within the trainee selection and recruitment process. Many strategies to mitigate bias and promote diversity were highlighted, though their impact on workforce diversity in pediatric training programs remains unknown.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the Alo Grant Diversity Fund (MLL) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant K23HD107178 (GT). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NIH or Altus Assessments.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

- Institutional grant from Alo Grant Diversity Fund (Langhan).

- Institutional grant from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant K23HD107178 (Tiyyagura).

Contributor Information

Gunjan Tiyyagura, Department of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Section of Emergency Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Jasmine Weiss, Department of Pediatrics, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC; Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

Michael P. Goldman, Department of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Section of Emergency Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Destanee M. Crawley, Department of Pediatrics, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

Melissa L. Langhan, Department of Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine, Section of Emergency Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn.

References

- 1.FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, et al. Diversity of the National Medical Student Body – four decades of inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1661–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montez K, Omoruyi EA, McNeal-Trice K, et al. Trends in race/ethnicity of pediatric residents and fellows: 2007–2019. Pediatrics. 2021;148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qt Capers, Clinchot D, McDougle L, et al. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med. 2017;92:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beheshtian E, Jalilianhasanpour R, Sahraian S, et al. Fellowship candidate factors considered by program directors. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poirier MP, Pruitt CW. Factors used by pediatric emergency medicine program directors to select their fellows. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moody J Faculty Diversity: Removing the Barriers. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams M, Kim EJ, Pappas K, et al. The impact of United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) step 1 cutoff scores on recruitment of underrepresented minorities in medicine: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3:e2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross DA, Boatright D, Nunez-Smith M, et al. Differences in words used to describe racial and gender groups in medical student performance evaluations. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang N, Blissett S, Anderson D, et al. Race and gender bias in internal medicine program director letters of recommendation. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill KA, Desai MM, Chaudhry SI, et al. Association of marginalized identities with alpha omega alpha honor society and gold humanism honor society membership among medical students. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2229062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen M, Chaudhry SI, Asabor E, et al. Variation in research experiences and publications during medical school by sex and race and ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2238520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarman BT, Kallies KJ, Joshi ART, et al. Underrepresented minorities are underrepresented among general surgery applicants selected to interview. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:e15–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edmond MB, Deschenes JL, Eckler M, et al. Racial bias in using USMLE step 1 scores to grant internal medicine residency interviews. Acad Med. 2001;76:1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassam AF, Cortez AR, Winer LK, et al. Swipe right for surgical residency: exploring the unconscious bias in resident selection. Surgery. 2020;168:724–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swanson WS, Harris MC, Master C, et al. The impact of the interview in pediatric residency selection. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simone K, Ahmed RA, Konkin J, et al. What are the features of targeted or system-wide initiatives that affect diversity in health professions trainees? A BEME systematic review: BEME guide no. 50. Med Teach. 2018;40:762–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sungar WG, Angerhofer C, McCormick T, et al. Implementation of holistic review into emergency medicine residency application screening to improve recruitment of underrepresented in medicine applicants. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:S10–s18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: Specialties Matching Service 2022 Appointment Year. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119:1442–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss AL, Corbin, Juliet M. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaDonna KA, Artino AR Jr, Balmer DF. Beyond the guise of saturation: rigor and qualitative interview data. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:607–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association of American Medical Colleges. Underrepresentated in medicine definition 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacob JA. AAMC report examines how to increase the pipeline of Black men entering medical school. JAMA. 2015;314:2222–2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dort JM, Trickey AW, Kallies KJ, et al. Applicant characteristics associated with selection for ranking at independent surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2015;72:e123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neely D, Feinglass J, Wallace WH. Developing a predictive model to assess applicants to an internal medicine residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:129–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villwock JA, Hamill CS, Sale KA, et al. Beyond the USMLE: the STAR algorithm for initial residency applicant screening and interview selection. J Surg Res. 2019;235:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosslet GT, Carlos WG 3rd, Tybor DJ, et al. Multicenter validation of a customizable scoring tool for selection of trainees for a residency or fellowship program. The EAST-IST study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marbin J, Rosenbluth G, Brim R, et al. Improving diversity in pediatric residency selection: using an equity framework to implement holistic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powers A, Gerull KM, Rothman R, et al. Race- and gender-based differences in descriptions of applicants in the letters of recommendation for orthopaedic surgery residency. JB JS Open Access. 2020;5:e20.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alvarez A, Mannix A, Davenport D, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in ratings in the medical student Standardized Letters of Evaluation (SLOE). J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:549–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith KW, Amini R, Banerjee M, et al. The feasibility of blinding residency programs to USMLE step 1 scores during GME application, interview, and match processes. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:276–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aibana O, Swails JL, Flores RJ, et al. Bridging the gap: holistic review to increase diversity in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burks CA, Russell TI, Goss D, et al. Strategies to increase racial and ethnic diversity in the surgical workforce: a state of the art review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;166:1182–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swails JL, Adams S, Hormann M, et al. Mission-based filters in the electronic residency application service: saving time and promoting diversity. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jimenez RB, Pinnix CC, Juang T, et al. Using holistic residency applicant review and selection in radiation oncology to enhance diversity and inclusion-an ASTRO SCAROP-ADROP-ARRO collaboration. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2023;116:334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haag J, Sanders BE, Walker Keach J, et al. Impact of blinding interviewers to written applications on ranking of gynecologic oncology fellowship applicants from groups underrepresented in medicine. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2022;39:100935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quintero AJ, Segal LS, King TS, et al. The personal interview: assessing the potential for personality similarity to bias the selection of orthopaedic residents. Acad Med. 2009;84:1364–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langhan ML, Goldman MP, Tiyyagura G. Can behavior-based interviews reduce bias in fellowship applicant assessment? Acad Pediatr. 2022;22:478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates T, Mutha S, Coffman J. Practicing holistic review in medical education. Healthforce Center at UCSF; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amos AJ, Lee K, Sen Gupta T, et al. Systematic review of specialist selection methods with implications for diversity in the medical workforce. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]