Abstract

Background

Sachet water is the most common form of portable water commercially available in Nigeria.

Methodology

Using the murine sperm count and sperm abnormality assay, the germ cell toxicity of five common commercially available sachet waters in Nigeria was assessed in this study. The levels of hormones such as Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH), Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Total Testosterone (TT); and activities of catalase (CAT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were evaluated. The heavy metal and physicochemical parameters of the sachet waters were also analyzed. Healthy male mice were allowed to freely drink the sachet waters for 35 days after which they were sacrificed.

Results

The findings indicated that the concentrations of some heavy metals (As, Cr, and Cd) in the sachet waters exceeded the limit by regulatory organizations. The data of the total carcinogenic risk (TCR) and total non-carcinogenic risk (THQ) of some heavy metals associated with the ingestion of sachet water for adults and children showed that the values exceeded the acceptable threshold, and thus, is indicative of a high non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks. The data of the sperm abnormality assay showed that in the exposed mice, the five sachet waters induced a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in abnormal sperm cells and a significantly lower mean sperm count. Additionally noted were changes in the serum activities of TT, FSH, ALP, AST, ALT, and LH.

Conclusion

Thus, the sachet waters studied contained agents that can induce reproductive toxicity in exposed humans. This is of public health importance and calls for immediate action by regulatory bodies.

Keywords: sachet water, heavy metals, sex hormones, male reproductive toxicity, health risk assessment, clinical chemistry, sperm morphology assessment

Introduction

Water is a transparent, tasteless, odorless and almost colorless inorganic chemical substance. It is the major component of Earth’s hydrosphere and serves as a solvent in the fluid of all known living things.1 Human health and survival depend on water, and maintaining life requires access to clean, safe drinking water. Numerous bodily processes, such as digestion, circulation, and temperature regulation, depend heavily on water. It is essential for maintaining healthy skin, hair, and nails as well as for the normal operation of organs like the liver and kidneys.2 Potable water refers to water that is safe for human consumption and devoid of dangerous impurities. Potable water should adhere to a number of requirements set forth by the World Health Organization (WHO), including not containing any radioactive dangers, chemicals, or pathogenic microbes.2 Potable water must go through a number of processes and testing to verify that it is free of dangerous toxicants and impurities before it is approved for consumption. Filtration, disinfection, and chemical treatment are a few examples of these treatments.3

It is essential for human wellbeing an access to clean and safe drinking water. Water sachets, also known as sachet waters, are a popular way to sell pre-filtered or sanitized water in plastic, heat-sealed packets in several regions of the global south. They are particularly well-liked in Africa.1 Compared to plastic bottles, water sachets are easier to transport and less expensive to make.4 Water dealers may refer their sachet water as “pure water” in various nations. In Nigeria, it is the most common type of water sold and use at homes, work and in different functions. Nigeria’s main water supply comes from groundwater that is collected from boreholes and wells. However, pollution from a variety of sources, such as commercial operations, agricultural methods, and household waste disposal, have an impact on the water quality in Nigeria.5 Due to lack of and adequate implementation of existing regulations, many sachet waters produced in Nigeria are below the standard for portable water. This has made many people in Nigeria to still lack access to safe and clean drinking water, despite the fact that it is a fundamental human right.

Water toxicity is an important public health issue with the potential of causing various health problems in humans. According to a study by Ogunkunle et al.5 the water quality in Nigeria is generally poor, with high levels of total dissolved solids (TDS), turbidity, and iron (Fe). The wells and boreholes in some areas were contaminated with heavy metals including lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), which can cause various health problems, including kidney damage, nerve damage, and anemia. Exposure to contaminated water can lead to gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. It can also cause neurological problems such as numbness, tingling, and tremors.6 Furthermore, exposure to toxic substances in water can result in skin issues like rashes, itching, and irritation. Respiratory issues including coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath can also occur by inhaling hazardous compounds from contaminated water, such as chlorine gas.7 Exposure to toxic chemicals and heavy metals in water has also been linked to infertility in both men and women. According to a study by Adebowale et al.8 exposure to Pb and cadmium (Cd) in drinking water was associated with decreased sperm count and motility in men. Similarly, a study by Onyema et al.9 found that exposure to heavy metals through ingestion of water was associated with reduced ovarian function and increased risk of infertility in women. Moreover, Wigle et al.10 suggested that water toxicity can lead to reproductive problems such as infertility, miscarriage, and birth defects due to exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and heavy metals. Exposure to certain toxic chemicals found in contaminated water, such as benzene and vinyl chloride, has also been linked with an increased risk of cancer.

Monitoring of drinking water quality is important to preserve public health from the adverse effects of contaminated water. To achieve this, chemical analysis of drinking water has been generally employed. Chemical analysis of water is a critical process that involves the measurement of the concentrations of various dissolved substances present in the water.11 The analysis typically includes the measurement of several parameters: pH, alkalinity, hardness, dissolved oxygen, total dissolved solids, and the concentrations of various ions, minerals and metals. However, chemical analysis of water is not enough to determine its potability, as certain chemicals can be present at acceptable concentration but become very potent when in combination with other chemicals. Therefore, biological analysis using animal models is required to study the potential ability of drinking water to induce germ cell mutation with possible reproductive and generational consequences. Hence, this study aimed at assessing the chemical constituents of five major sachet water in Nigeria and their potential germ cell genotoxicity using the murine sperm abnormality test and sperm count.

Materials and methods

Collection of sachet water and chemical analysis

Five different sachet waters from five popular brands in Nigeria were collected from their vendors. Due to confidentiality reason the names of the sachet water companies have been anonymized, hence, the sachet waters were labeled samples A, B, C, D, and E, respectively, and the concentrations of selected heavy metals (Pb, Chromium (Cr), Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Iron (Fe), Zn, Manganese (Mn), and Cu) and physiochemical parameters (pH and Alkalinity) were analyzed according to standard analytical methods.2,12,13 Briefly, on 100 mL of each sample, sample digestion was performed and the volume reduced to 3–5 mL after heating with concentrated nitric acid (HNO3). This volume was then made up with 0.1 N HNO3 to 10 mL.before using Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) Buck Scientific 210 VGP spectrophotometer (LAMOTTE) to measure the heavy metal’s concentrations.

Health-risk assessment

The sachet waters used for this study are usually for drinking in Nigeria by local residents, thus, the analysis of health risks viz-a-vis carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks caused by heavy metals was considered following ingestion pathway alone. The formulas used were as follow14,15:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

where BW = average body weight (kg); Ci = concentration of a heavy metal, i (mg/L); CDIi = chronic daily intake (mg/kg/d); TCR = total carcinogenic risk; CRi = carcinogenic risk caused by a heavy metal, i; SFi = cancer slope factor of heavy metal, i (kg/d/mg); IR = ingestion rate of water (L/d); EF = exposure frequency (d/a); ED = exposure duration (a); RfDi = reference dose of heavy metal, i (mg/kg/d); AT = average time of exposure (d); HQi = non-carcinogenic risk caused by a heavy metal, i; and THQ = total non-carcinogenic risk. The values of RfDi, BW, AT, SFi, ED, EF, and IR for adults and children are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Parameters of risk assessment of toxic metals for this study as adapted from Bai et al. (2022).

| Description | Exposure parameters | Adult | Child |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ingestion rate of water (Litre/day) | IR | 2.50 | 0.78 |

| Exposure frequency (day/annum) | EF | 350.00 | 350.00 |

| Exposure duration (years) | ED | 26.00 | 6.00 |

| Average body weight (kg) | BW | 80.00 | 15.00 |

| Average time of exposure (days) | AT | 8760.00 | 2190.00 |

Table 3.

Reference dose (RfDs) and cancer slope factor (SF) of heavy metals (mg kg−1 day−1) adopted in this study, values adopted from Bai et al. (2022).

| Metals | Cr | Cd | As | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RfDi | 0.003 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 0.3 |

| SFi | 0.500 | 6.1000 | 1.5000 | – |

“-” data not available in the literature.

For the carcinogenic risk, if CRi or TCR > 10−4, there may be a high carcinogenic risk to humans, if CRi or TCR < 10−6, the carcinogenic risk could be negligible, and if 10−6 < CRi or TCR < 10−4, there is an acceptable carcinogenic risk to humans. For the non-carcinogenic risk, if HQi or THQ > 1, there may be adverse effects on human health, whereas if HQi or THQ < 1, there are no adverse effects on human health.14

Biological material

Healthy Swiss male mice (Mus musculus) of 12–14 weeks old were purchased from a breeder at Ibadan, Oyo State. Throughout this study period, the animals were housed in the same room at Federal University of Technology, Akure, in wooden cages lined with wood shavings. Pelleted feed (®Ladokun) and clean tap water were given to them for two weeks for acclimatization. Animals were cared for according to the guidelines for the use and care for animals of our Institution and ethical clearance was received from the ethical committee of the same Institution before the start of the experiment.

Sperm morphology assay

After acclimatization, the mice were grouped into seven based on their average body weight (40 g) with five animals per group. Group 1 (positive control) animals were injected intraperitoneally for five consecutive days with 0.4 mL of cyclophosphamide while animals in groups 2–7 were allowed to freely drink well water (negative control) and sachet water A-E for 5 consecutive weeks. The animals were sacrificed through cervical dislocation after exposure for 35 days. The caudal epididymis was surgically removed, each in different petri dish, teased to allow the sperm cells to separate from the epididymis tissues and minced in the saline solution before staining for 45 min with 1% Eosin Y. A thin smear of the sperm suspension was made on grease-free, clean microscope slides after mixing well with a plastic pipette and air dried before examining it under a 1,000× magnification. Four thousand (4,000) sperm cells in total were examined for morphological aberrations in each mouse. The percentage frequency of the aberration was calculated by dividing the total number of aberrations observed over the total cell counted multiplied by 100.

Sperm count

Mice utilized for sperm morphology assay were also used for sperm count. The testes’ caput epididymis was surgically removed, pulverized in physiological saline, and the filtration of the suspension was done using a mesh cloth to get rid of any remaining tissue fragments. Subsequently, a drop of eosin Y (1%) was added to the filtrate for 30 min. In a leukocyte hemocytometer, the stained sperm suspension was carefully drawn until it reached the 0.5 mark, and phosphate buffered saline was used to mix it until it reached the 11 mark. A Neubauer counting chamber was then used for the counting of the diluted suspension under the light microscope at 400×. The average number of sperm per milliliter of suspension was calculated by combining the sperm counts of all the mice in each group.

Biochemical analysis

To get a clear supernatant, ice-cold buffer (0.1 M phosphate, pH = 7.4) was used to homogenize the testes of the animals. Centrifugation of the mixture was carried out at 4 °C for 15 min at 10,000 rpm. In accordance with the methodology of Gornal et al.,16 total amount of protein in the homogenate was determined at 540 nm in a spectrophotometer (SP-V5000) using the Biuret reagent, with Bovine Serum Albumin as the standard. Using commercial kits from Fortress Kit (England), enzyme’s activities of catalase (CAT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), superoxide dismutase (SOD), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) were measured.

Total testosterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH) assays

Blood collected from animals used in the sperm morphology assay were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min to separate the serum. Then, the quantities of TT, FSH, and LH present were measured using chemiluminescent immunoassay through commercially available ELISA kits and an automated Unicel Dlx 800 Access Immunoassay System (Beckman Coulter, Inc., USA).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of generated data was carried out using SPSS® 23.0 statistical package. For the assays, the data derived were reported as mean ± standard error. Sperm morphology assay results were given with 95% confidence interval, and ANOVA was used to test significance. LSD, Duncan, and Dunnett t- test were used to test the significance at various concentration levels. At probability levels of 0.05, the variations between each of the sample group and the negative control group were analyzed.

Results

Heavy metal and physicochemical analyses

Table 1 contained information about the physicochemical and heavy metal characteristics of the sachet waters in this study. The concentrations of Zn, Cu, Mg, and Fe were below the maximum permissible limits by regulatory agencies, however, As, Cd and Cr concentrations were higher in all the five sachet water than the maximum permissible limits by regulatory agencies.2,12,13 The pH and total alkalinity of the water samples were within the regulatory range.

Table 1.

Heavy metal and physicochemical characteristics of five common sachet waters in Nigeria.

| Samples | Cu | Cd | Cr | As | Fe | Mn | Zn | Alkalinity | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.100 | 0.003 | 0.088 | 0.025 | 0.084 | 0.068 | 0.486 | 57.25 | 7. 52 |

| B | 0.114 | 0.004 | 0.170 | 0.001 | 0.091 | 0.001 | 0.713 | 60.50 | 7.45 |

| C | 0.116 | 0.007 | 0.110 | 0.015 | 0.078 | 0.097 | 0.582 | 56.00 | 7.64 |

| D | 0.100 | 0.006 | 0.077 | 0.011 | 0.100 | 0.075 | 0.537 | 59.25 | 7.78 |

| E | 0.113 | 0.003 | 0.110 | 0.013 | 0.073 | 0.099 | 0.488 | 53.00 | 7.74 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.109 ± 0.13 | 0.005 ± 0.01 | 0.111 ± 0.21 | 0.013 ± 0.11 | 0.085 ± 0.07 | 0.068 ± 0.15 | 0.561 ± 0.30 | 57.20 ± 0.81 | 7.63 ± 0.02 |

| WHOa | 2 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.01 | – | 0.4 | 3 | 50–200 | 6.5–8.5 |

| SONb | 2 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.01 | – | 0.4 | 5 | – | 6.5–8.5 |

| USEPAc | 1.3 | 0.005 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 5 | – | 6.5–8.5 |

Except for pH which has no unit, all parameters are in mg/L.

aWHO (2017).

bSON (2007).

cUSEPA (2021). “-” data not available.

Human health-risk assessment

Carcinogenic risk

Table 4 shows the carcinogenic risks of three heavy metals (Cr, Cd, and As) associated with the ingestion of sachet waters for adults and children. The carcinogenic risk data showed high carcinogenic risk for Cr, Cd, and As in both children and adults with children having higher carcinogenic risk [Cr (mean = 0.0028), Cd (mean = 0.0018) and As (mean = 0.0011)] than adults [Cr (mean = 0.0018), Cd (mean = 0.0010) and As (mean = 0.0006)] as the CRs values exceeded the threshold of 1 × 10−4. The carcinogenic risk of the metals is in the order: Cr > Cd > As for both children and adults.

Table 4.

Chronic daily dose, carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks of heavy metals from the studied sachet water by children and adults through ingestion.

| Children | Adults | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | CDI | CR | TCR | HQ | THQ | CDI | CR | TCR | HQ | THQ | |

| Cr | Min | 0.0038 | 0.0019 | 1.2667 | 0.0025 | 0.0013 | 0.8333 | ||||

| Max | 0.0085 | 0.0043 | 2.8333 | 0.0055 | 0.0028 | 1.8333 | |||||

| Mean | 0.0055 | 0.0028 | 1.8333 | 0.0036 | 0.0018 | 1.2000 | |||||

| As | Min | 0.000050 | 0.000075 | 0.1667 | 0.000032 | 0.000048 | 0.1067 | ||||

| Max | 0.0013 | 0.0020 | 4.3333 | 0.0008 | 0.0012 | 2.7000 | |||||

| Mean | 0.0007 | 0.0011 | 2.3333 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 1.4000 | |||||

| Cd | Min | 0.0002 | 0.0012 | 0.4000 | 0.000097 | 0.0006 | 0.1940 | ||||

| Max | 0.0004 | 0.0024 | 0.8000 | 0.0002 | 0.0014 | 0.4600 | |||||

| Mean | 0.0003 | 0.0018 | 0.0057 | 0.6000 | 0.0002 | 0.0010 | 0.0034 | 0.3200 | |||

| Fe | Min | 0.0036 | 0.0120 | 0.0024 | 0.0079 | ||||||

| Max | 0.0050 | 0.0167 | 0.0033 | 0.0108 | |||||||

| Mean | 0.0042 | 0.0140 | 4.7806 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 2.9204 | |||||

Non-carcinogenic risk

For the non-carcinogenic risks of Cd and Fe, the HQ values in the sachet waters were lower than 1, however, the HQ values for Cr and As were greater than 1 for both children and adults. The order of the average HQs of the heavy metals in the sachet waters was as follows: Cr > As > Cd > Fe (Table 4). A higher non-carcinogenic risk of each metal was observed in the children compared to the corresponding adults, with Cr in children having the highest mean non-carcinogenic risk.

Total health risk

Total carcinogenic risk (TCR)

Total carcinogenic risks of Cd, Cr, and As in the present study for both adults and children were > 1 × 10−4 in the sachet waters (Table 4). The carcinogenic risks generated for Cr were far greater than those of As and Cd, accounting for 49.12% and 52.94% of the TCR in children and adults, respectively. Generally, the TCR in children was 59.65% higher than the TCR in adults.

Total non-carcinogenic risk

The values of the total Hazard Quotient (THQ) caused by non-carcinogenic heavy metals in the sachet waters for adults and children were higher than 1 (Table 4). The THQ for children and adults were 4.78 and 2.92, respectively. The total non-carcinogenic risk generated by As was the highest among the non-carcinogenic heavy metals, accounting for 48.80% and 47.95% of the THQ for children and adults, respectively. This was followed by Cr, which accounted for 38.35% and 41.1% of the THQ for children and adults, respectively.

Sperm morphology assay

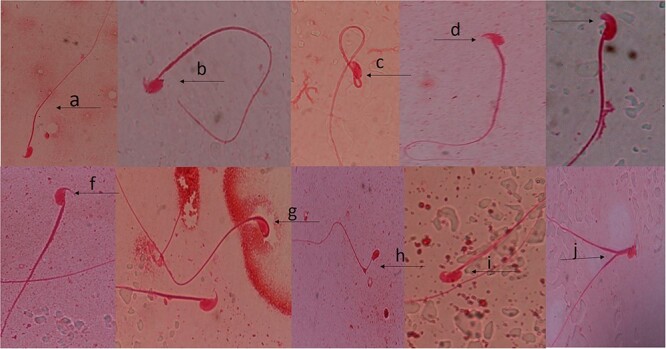

The result of the sperm morphology assay revealed a statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase in mice exposed to the different sachet waters when compare to the negative control group (Table 5). For the positive and negative controls, the average sperm aberrations were 281.00 and 96.00, respectively. Samples A, B, C, D and E induced abnormal sperm morphology with means of 118.80, 120.80, 157.80, 115.80, and 140.40, respectively. The percentage frequency of aberration induced by the five sachet water varied from 18.7%–24.6%. The observed aberrations in the sperm cells of exposed mice include amorphous head, double head, distal droplet, folded sperm, knobbed hook, no hook, pin head, kidney head, short hook, banana head, swollen hook, long hook, hook at wrong angle and wrong tail attachment (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Percentage frequency and mean sperm abnormalities in albino mice exposed to five common sachet waters in Nigeria.

| Samples | Total cells counted | Percentage frequency of abnormalities | Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 4,000 | 12.3 | 96.00 ± 1.75 |

| A | 4,000 | 19.1a | 118.80 ± 0.64a |

| B | 4,000 | 20.4a | 120.80 ± 1.82a |

| C | 4,000 | 24.6a | 157.80 ± 1.80a |

| D | 4,000 | 18.7a | 115.80 ± 0.38a |

| E | 4,000 | 22.8a | 140.40 ± 1.26a |

| Positive | 4,000 | 39.7a | 281.00 ± 0.02a |

aSignificant at P < 0.5 level. Negative—well water, Positive—cyclophosphamide; SEM—Standard error of the mean.

Fig. 1.

Representative sperm morphology abnormalities induced in mice exposed to five major sachet water in Nigeria. (a) Normal sperm cell (b) wrong tail attachment (c) folded sperm (d) sperm cell with short hook (e) banana head (f) hook at wrong angle (g) amorphous head (h) projecting filament from midpiece (i) knobbed hook (j) double tail (×100; 1% eosin Y).

Sperm count

Table 6 shows the average sperm count of mice exposed to the five sachet waters and the controls. The average sperm counts of the positive and negative controls were 8.83 × 104 and 8.51 × 106, respectively. All the five sachet water induced a numerical reduction in the average sperm count in the mice which varies from 8.24 × 106 to 6.47 × 106, however, when compared to the negative control group, only sachet water C showed a significant decrease.

Table 6.

Mean sperm count of mice exposed to five common sachet waters in Nigeria.

| Sample | Mean ± SE |

|---|---|

| Negative control | 8.51 × 106 |

| A | 8.20 × 106 |

| B | 8.15 × 106 |

| C | 6.47 × 106a |

| D | 8.10 × 106 |

| E | 8.24 × 106 |

| Positive control | 8.83 × 104a |

aSignificant at P < 0.5 level. Negative—well water, Positive—cyclophosphamide; SEM—Standard error of the mean.

Biochemical analysis

Table 7 presents the impact of various sachet waters on selected biochemical parameters in mice. The data showed a modulation of the activities of CAT, SOD, ALP, ALT, and AST as marker enzymes in the serum of the exposed mice for oxidative stress and liver injury. These activities were significantly different from those of the negative control. Significant (P < 0.05) increase was seen in the activities of ALP, AST, and ALT in comparison to the exposed mice in the negative control with a corresponding significant (P < 0.05) decrease in the activities of CAT and SOD were recorded.

Table 7.

The effects of five common sachet waters in Nigeria on some biochemical parameters in mice.

| Sample | AST(U/L) | ALT(U/L) | ALP(U/L) | CAT(U/mg protein) | SOD(U/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | 11.31 ± 0.10 | 8.96 ± 0.15 | 46.10 ± 0.11 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| A | 12.39 ± 0.21a | 9.79 ± 0.02a | 49.11 ± 0.01a | 0.07 ± 0.38a | 0.003 ± 0.005a |

| B | 12.83 ± 0.14a | 9.19 ± 0.01 | 48.36 ± 0.41a | 0.07 ± 0.02a | 0.003 ± 0.001a |

| C | 13.10 ± 0.90a | 11.13 ± 0.91a | 49.89 ± 0.02a | 0.06 ± 0.21a | 0.002 ± 0.002a |

| D | 12.31 ± 0.05a | 10.95 ± 0.05a | 48.37 ± 0.01a | 0.07 ± 0.74a | 0.003 ± 0.002a |

| E | 12.84 ± 0.12a | 9.22 ± 0.07a | 49.00 ± 0.52a | 0.06 ± 0.33a | 0.003 ± 0.003a |

| Positive control | 16.03 ± 0.50a | 14.39 ± 0.10a | 62.42 ± 1.93a | 0.05 ± 0.45a | 0.001 ± 0.001a |

aSignificant at P < 0.05 compared to the negative control; Negative—well water; Positive—Cyclophosphamide; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate amino transferase; ALP: Alkaline Phosphatase; CAT: Catalase; SOD: Superoxide dismutase; U/L: Units per liter.

Total testosterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) assays

Table 8 shows the serum concentrations of TT, LH and FSH in exposed mice. Compared to the negative control group, the serum concentrations of TT, LH and FSH significantly (P < 0.05) reduced in the exposed mice. The serum concentrations of TT reduced from 5.82 to 4.22 ng/mL in the exposed mice while the concentrations of LH and FSH varied from 1.35–1.08, and 0.16–0.14 mIU/mL, respectively.

Table 8.

Serum concentration of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and total testosterone (TT) in mice exposed to five common sachet waters.

| Sample | TT (ng/mL) | FSH (mIU/mL) | LH (mIU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | 6.38 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.21 | 1.81 ± 0.56 |

| A | 5.82 ± 0.45a | 0.14 ± 0.35a | 1.31 ± 0.04a |

| B | 5.58 ± 0.54a | 0.14 ± 0.28a | 1.35 ± 0.43a |

| C | 4.22 ± 0.43a | 0.16 ± 0.70a | 1.08 ± 0.67a |

| D | 5.45 ± 0.63a | 0.15 ± 0.08a | 1.33 ± 0.75a |

| E | 5.55 ± 0.22a | 0.14 ± 0.11a | 1.34 ± 0.24a |

| Positive | 4.64 ± 0.44a | 0.16 ± 0.42a | 0.51 ± 0.29a |

aSignificant at P < 0.05 compared to the negative control; Negative—well water; Positive—Cyclophosphamide; mIU/mL—milli-international units per milliliter.

Discussion

Water toxicity is a major global issue, especially in rural areas where access to clean portable drinking water is scarce. It is dangerous to drink water from sources like rivers and ponds since they are frequently contaminated with chemicals and microorganisms,17 hence, many people depend on the “perceived” processed clean water sold by different producers in sachet or plastic containers. In this study, five common commercially available sachet waters were analyzed for the presence of toxic metals and their biological effect was assessed through abnormal sperm morphology induction and alteration to the activities of certain enzymes in albino mice.

The data from this study revealed that some toxic metal concentrations in the drinking water were higher than the threshold permissible by regulatory agencies. Similar reports of water contamination have been documented in Nigeria. For example, a study found that 96.5% of surface water samples collected from different sources were contaminated with bacteria like Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These bacteria can induce illnesses like cholera, dysentery and typhoid fever, which can have severe consequences for human health.17 In addition to bacterial contamination, water sources in Nigeria were also reported to be contaminated with toxic chemicals such as Pb, As, Cr, and Cd.18 These chemicals can have adverse health effects on humans including developmental and reproductive problems.

The data of the carcinogenic risks of Cr, Cd, and As associated with the ingestion of sachet waters for adults and children in Nigeria showed that the CRs exceeded the threshold of 1 × 10−4, an indication of a high carcinogenic risk. The present study’s report on the potential carcinogenic risk of drinking the sachet waters contaminated with heavy metals is of public health importance as the carcinogenic risk is higher in children than in adults, putting the future generation at greater risk of metal toxicity with unimaginable consequences. Therefore, children should be more careful when consuming sachet water. Chromium was the most contributor to the carcinogenic risk in this study and this therefore calls for immediate treatment of sachet water in Nigeria for the elimination of chromium. Heavy-metal pollution might be a potential driver for cancer occurrence if continuous exposure through drinking of contaminated sachet water continues in the study areas.

For two elements (Cr and As,), the values of HQ were above 1 in the sachet waters, indicating the presence of non-carcinogenic risk which is possible through the ingestion of sachet water for adults and children. A total carcinogenic risk greater than 1 × 10−4 was recorded in the sachet waters, an indication that the TCR posed by carcinogenic heavy metals (Cr, As and Cd) presents a potential health risk for children and adults drinking the sachet waters. Cr in the sachet waters have the highest contribution to TCR in both children and adults resulting in considerable health risks. The carcinogenic risk in this study is in the order of Cr > Cd > As. Report from Sabzevar, Iran showed the carcinogenic risks for both adults and children through ingestion to be in the order of As > Cr > Cd.19 Similar reports on the carcinogenic risks associated with ingestion in Dalian, China, showed that the risk was mainly caused by Cr and As, while As caused the highest risk in Gopalganj, Bangladesh.20,21

The total HQ (THQ) values caused by non-carcinogenic heavy metals in the sachet waters for adults and children were higher than 1, which may negatively impact human health through the ingestion of the sachet waters. This is an indication that the sachet waters contained non-carcinogenic elements with the ability to cause human health hazards. Arsenic presents the highest non-carcinogenic risk and contributed the most to the THQ among the non-carcinogenic heavy metals in the sachet waters, this implies that the presence of As in sachet waters could cause lifetime health risks to the local residents. Moreover, Cd, Cr and Fe also contributed significantly to the non-carcinogenic risks in the sachet waters. Furthermore, although the HQ values from some individual non-carcinogenic heavy metals in the sachet waters were below the limit, the results indicated that the THQ values from many non-carcinogenic heavy metals exceeded the limit, with the effects of heavy-metal pollutants in the sachet waters through ingestion more pronounced in children. Studies from the Hetao Plain in Northern China and Southeast Iran22,23 have shown that As exposure poses a serious non-carcinogenic risk in groundwater which is consistent with the present results. A similar result of As being a major contributor to non-carcinogenic risk through ingestion of water was reported by Bai et al.24

Water toxicity can significantly impact human health, including reproductive health. Exposure to toxic chemicals in drinking water has been linked to infertility, particularly in men.18 Several studies have shown that exposure to certain chemicals found in drinking water, such as Pb, Cd, Cr, As, and pesticides can affect male reproductive health by reducing sperm count, motility, and morphology.25,26 Elinder and Jarup27 reported the carcinogenic potential of Cd in experimental animals while micronuclei strand breakage and chromosomal abnormalities have been documented to result from Cr exposure.28 Additionally, Cd and Cu in eukaryotic systems led to the formation of reactive oxygen species.29 According to a study, oxidative stress caused by Cd induced DNA damage and initiated apoptosis in human liver.30 Alteration of semen quality, testicular function, and hormonal imbalance of various animal species have been documented as induced by Cd.31 In an animal study, frequencies of sperm abnormalities increased after exposure to Cr.32,33 Waalkes et al.34 reported the spermatotoxic effect of As including reduced weight of testes and other accessory sex organs; and inhibited testicular steroidogenesis.35 Rahinetu36 also reported that long-term exposure to As, Cr, and Cd can cause cancer and toxicity in organ systems such as reproductive, urinary, skeletal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. The presence of toxic metals in popular sachet water sold across Nigeria calls for public health concern as this might be a source of adverse health effects for consumers. Also, this shows the lack of adequate monitoring policies for water production in the country or its enforcement.

The potential of the contaminated sachet water in this study to cause reproductive toxicity was assessed using murine sperm morphology assay. The abnormal sperm morphology in the mice exposed to some of the sachet waters increased to at least twice the level of the negative control in the sperm morphology assay, satisfying the conditions for a positive result. The sperm morphology assay is widely useful as a short-term assay for the detection of agents able to alter spermatogenesis. In chemically treated animals, it gives a clear indicator of the quality of sperm produced. The understanding of the genetic basis of chemically molded defects in mice is a key focus of studies analyzing the genetic implications of sperm alterations which is chemically induced. Numerous lines of evidence imply that the damage to the male germ cell’s genetic material reflects an induced alteration in sperm morphology.37,38 Wyrobek et al.39 and Alabi et al.33 also noted that a positive finding shows the sample’s potential to disrupt sperm formation when male germ cells come in contact with the sample in vivo.

The ability of heavy metals and other un-identified chemicals in the sachet waters to disrupt sperm formation was demonstrated by several abnormalities in sperm cell shape observed in this study. Both the sperm cell motility and quality of the genetic material are impacted by these abnormalities. Although, abnormal head defects (amorphous, double head, kidney-shaped, banana) can greatly lower spermatozoa's in vivo and in vitro fertilization capacity, they do not appear to impair spermatozoa's motility.40 According to Nikolatos et al.41 sperm cell without head may be indicator of other sperm problems that seriously affect fertility. There is an association between male sterility and fertility with sperm abnormalities in most species and a substantial role is played by the structure in fertilization and conception.42 Sperm cells with a pin head have little to no paternal DNA; sperm cells with a double head or double tail might cause abnormal zygote formation; and sperm cells that are folded and have distal droplets indicate that their tails have been damaged and they have lost their ability to move.43 For fertilization, sperm cells without or with a knobbed hook would not be able to attach to an egg, infertility is associated with sperm cells with distal droplet because sperm cells motility is hindered by droplet,44 and paternal DNA’s genetic material or abnormal chromatin are often present in sperm cells with amorphous head.43

The increased frequency of aberrant sperm cells has generated diverse opinion on the precise reason for the increase. An abnormal chromosome,45 point mutation,46 minor alteration in the DNA of the testes (Giri et al. 2002),47 and error during spermatogenesis in the process of spermatozoa differentiation48 have been hypothesized as the cause of induction of abnormal sperms. The influence of the chemical constituents of the sachet waters on genes accountable for acrosomes characteristic expression may be responsible for the abnormal sperm morphologies.37,49 Menkveld et al.50 attributed tail coiling to aging of sperm cells and suggested that bended mid-piece had grown from the wrong centriole. Disorganization of the acrosomal membrane are assumed to be responsible for abnormalities with the hook, often resulting to a change in the nuclear shape. Numerous sex-linked and autosomal genes genetically control sperm cell morphology, hence, abnormal population of sperm formed in this present study is most likely as a result of the mutagenic effects of the chemical constituents of the sachet waters on the germ cell chromosomes at a specified gene loci which is involved in normal sperm structure maintenance. Therefore, the result in this study showed that some sachet waters in Nigeria contained chemical mutagens which can cause reproductive toxicity and damage the DNA.

Despite the diverse opinion on the importance of sperm morphology, it is universally acknowledged that when determining the potency of sperm for fertility, sperm morphological anomalies are important.51 Lewis and Aitken52 reported that spermatozoa with damaged DNA can be responsible for contribution of damaged genomes to the oocytes with adverse effect on fertilization, embryonic, foetal, and postnatal development. Therefore, the abnormal sperm cell’s induction by the sachet waters is important to public health as this might have a reproductive effect on the exposed local residents.

This study further revealed a reduction in sperm cell production due to exposure to the test agent. This is evident in the significant decrease in the average sperm count of mice exposed to the sachet water. The average data derived from the aberrant sperm cells revealed that interference by the constituents of the sachet water with the genetic processes involved in sperm formation in exposed mice can occur which was authenticated by the significant reduction in the average sperm count of exposed mice in comparison with negative control. This suggests that the sachet water is not only capable of disrupting sperm formation but also reducing sperm production and viability. The chances of fertility is reduce as a result of reduced sperm count, and this may also lead to problems with sexual functions such as erectile dysfunction, a lump in the testicle area, pain, low libido and swelling.

In this study, the biochemical parameters assessed in the experimental animals are useful indicators in measuring the toxicity and oxidative stress induced by sachet water for subsequent inference in human. The activities of ALT, ALP, and AST in the sachet water-exposed mice were significantly modulated. The evaluation of liver and kidney cell injury routinely involves serum activities of ALP, AST, and ALT.38 Kaplan53 reported that in the periportal hepatocytes are found these cytosolic enzymes and their serum activities can increase due to leakage or damage of the cellular membrane.53 The detection of these enzymes in the serum could be a biochemical indicator of a potential kidney or acute liver damage and leakage into the bloodstream.46

Given that oxidative stress is thought to have a role in the abnormal sperm cell formation process, therefore, the present study examined how two antioxidant enzyme activities are modulated in exposed mice. Among the crucial antioxidant enzymes that guard against oxidative stress are CAT and SOD. Superoxide is dismutated into hydrogen peroxide by SOD, while, in turn, cellular hydrogen peroxide is destroyed by CAT to produce water and oxygen. The result of the present study indicated that the sachet waters significantly decreased CAT and SOD activities in the exposed mice, indicating potential oxidative stress due to the constituents of the sachet waters.

The level of gonadotropic hormones (hormones that control spermatogenesis) in the exposed mice was also evaluated in order to further understand the mechanism of abnormal sperm cells induction. The data revealed that the serum concentrations of FSH, TT and LH in exposed mice were significantly reduced by the sachet waters. A relationship between semen quality parameters and the levels of circulation of certain reproductive hormones has been previously reported in men.54,55 The formation of spermatozoid requires TT, FSH, and LH. Whereas spermatogenesis enhances Sertoli cell binding to FSH, LH induces TT production in Leydig cells. This current study indicate that in sperm morphology formation, TT, LH, and FSH contributed actively since the exposed mice had a significant reduction in the number of normal sperm cells when the concentrations of TT, LH and FSH significantly decreased. According to Weinbauer et al.56 the reduction of FSH and LH to a critically low level reported in this study suggests an androgen deficiency because FSH and LH as pituitary gonadotropins are crucial for controlling spermatogenesis. A significant decrease of 30%–40% is always observed in the number of Sertoli cells when compared to the normal development of the testis if there is a low level of FSH.57 According to Sharpe et al.57 and Abel et al.,58 this is very significant because the quantity of sperm produced is determined by the Sertoli cells, as it can enhance a particular maximum number of germ cells. Therefore, the low level of FSH in this study suggests a possible production of low sperm in the exposed mice. This is in agreement with the result of the sperm count, where a reduction in the mean sperm count was recorded in the mice exposed to the sachet water. Infertility caused by a change in the normal function of the testes may result from failure of the pituitary to secret LH and FSH.59 In addition to acting as a paracrine agent which enhances spermatogenesis locally in Sertoli cells, TT provides feedback for LH secretion. According to Meeker et al.60 this indicates that disruption in the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis and compensatory mechanisms may be linked to sperm abnormalities in this study. We believe that the chemical constituents of the sachet water, some of which were analyzed in the present study are responsible for the enzyme activity modulation and reproductive toxicity observed.

Conclusion

Five common commercially available sachet waters in Nigeria are contaminated with toxic metals and induced reproductive abnormalities in mice. The observed reproductive abnormalities was as a result of the high level of Cr, As, Cd, and some physicochemical parameters. As, Cd, and Cr present in the sachet waters can cause carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks, especially in children. The activities of AST, ALT, ALP, CAT, and SOD were also modulated by the sachet waters with the concentrations of gonadotropic hormones (FSH, LH) and testosterone altered. This study showed the need for better monitoring of the production companies and processes of sachet water in Nigeria. There is need for a more comprehensive study of as many drinking water sources in Nigeria as possible to safeguard the health of her populace.

Contributor Information

Okunola Adenrele Alabi, Department of Biology, Federal University of Technology, 340110, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria; Department of Biotechnology, Federal University of Technology, 340110, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Olufunbi Esther Lawrence, Department of Biotechnology, Federal University of Technology, 340110, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Funmilayo Esther Ayeni, Department of Biology, Federal University of Technology, 340110, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

John A V Olumurewa, Department of Biotechnology, Federal University of Technology, 340110, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria.

Author contributions

Okunola Adenrele Alabi, Olufunbi Esther Lawrence, Funmilayo Esther Ayeni and John A. V. Olumurewa: contributed to the study conception and design. Okunola Adenrele Alabi, Olufunbi Esther Lawrence and Funmilayo E. Ayeni: performed material preparation, data collection, and analysis. Okunola Adenrele Alabi and Funmilayo Esther Ayeni: wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was not funded by any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Lerner S. Africa’s exploding plastic nightmare: As Africa drowns in garbage, the plastics business keeps booming. The Intercept; 2020. Denver, USA.[Accessed: 2023 November 6th]. Available at: https://theintercept.com/2020/04/19/coronavirus-africa-plastic-waste/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . Guidelines for drinking-water quality. 2017. USA. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549950.

- 3. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) . Drinking water standards and regulations. 2021. USA. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/dwstandardsregulation0s.

- 4. Stoler J, Weeks JR, Fink G. Sachet drinking water in Ghana’s Accra-Tema metropolitan area: past, present, and future. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. 2012:2(4):356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ogunkunle OA, Ojo OO, Akinbile CO. Water quality assessment of groundwater sources in Akure, Southwest Nigeria. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018:25(9):8288–8299. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Järup L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br Med Bull. 2003:68(1):167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. International Energy Agency . World energy model 2020. Japan. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/bc4936dc-73f1-47c3-8064-0784ae6f85a3/WEM_Documentation_WEO2020.pdf.

- 8. Adebowale TO, Akinboro A, Olabode TO. Heavy metals in drinking water and their association with semen quality among male partners of infertile couples in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. BMC Urolog. 2019:19(1):109. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Onyema I, Ezeonye OU, Akunna JC. Environmental exposure to heavy metals and their impacts on female reproductive health: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020:27(5):4681–4698. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wigle DT, Arbuckle TE, Turner MC, Bérubé A, Yang Q, Liu S, Krewski D. Epidemiologic evidence of relationships between reproductive and child health outcomes and environmental chemical contaminants. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008:11(5–6):373–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh KR, Dutta R, Kalamdhad AS, Kumar B. Review of existing heavy metal contamination indices and development of an entropy-based improved indexing approach. Environ Dev Sustain. 2020:22(8):7847–7864. [Google Scholar]

- 12. SON . Nigerian standard for drinking water quality. In: Nigeria industrial standard NIS 554; 2007. Lagos. ICS 13.060.20

- 13. USEPA . Drinking water regulations; 2021. [Accessed 2023 Nov 16]. http://water.epa.gov/drink/contaminants/index.cfm#List.

- 14. USEPA . Risk assessment guidance for superfund volume I: human health evaluation manual (part E, supplemental guidance for dermal risk assessment) final; Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation U.S., Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC, USA: US EPA; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang ZY, Su Q, Wang S, Gao ZJ, Liu JT. Spatial distribution and health risk assessment of dissolved heavy metals in groundwater of eastern China coastal zone. Environ Pollut. 2021:290:118016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gornal AG, Bardawill CJ, David MM. Determination of serum protein by means of biuret reaction. J Biol Chem. 1949:177(2):751–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iroegbu CU, Nwachukwu NC, Orji FA. Bacteriological quality of surface waters in Nigeria: a systematic review. J Environ Sci Health Part A. 2017:52(3):194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olatunji OS, Olusola OI. Environmental pollution in Nigeria: issues and solutions. Environ Pollut Impact Pub Health. 2019:10(8):45–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shams M, Nezhad NT, Dehghan A, Alidadi H, Paydarb M, Mohammadi AA, Zarei A. Heavy metals exposure, carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic human health risks assessment of groundwater around mines in Joghatai. Iran Int J Environ Anal Chem. 2020:102(8):1884–1899. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rahman MM, Islam MA, Bodrud-Doza M, Muhib MI, Zahid A, Shammi M, Tareq SM, Kurasaki M. Spatio-temporal assessment of groundwater quality and human health risk: a case study in Gopalganj, Bangladesh. Exposure Health. 2017:10(3):167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dong WW, Zhang Y, Quan X. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and pesticides: a case study in the main drinking water source in Dalian, China. Chemosphere. 2020:242:125113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen LZ, Ma T, Wang YX, Zheng JJ. Health risks associated with multiple metal (loid)s in groundwater: a case study at Hetao plain, northern China. Environ Pollut. 2020:263(Pt B):114562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eslami H, Esmaeili A, Razaeian M, Salari M, Hosseini AN, Mobini M, Barani A. Potentially toxic metal concentration, spatial distribution, and health risk assessment in drinking groundwater resources of Southeast Iran. Geosci Front. 2022:13(1):101276. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bai M, Zhang C, Bai Y, Wang T, Qu S, Qi H, Zhang M, Tan C, Zhang C. Occurrence and health risks of heavy metals in drinking water of self-supplied wells in northern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022:19(19):12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hong YC, Park EY, Park MS, Ko JA, Oh SY, Kim H, Ha EH. Community level exposure to chemicals and oxidative stress in adult population. Toxicol Lett. 2008:176(2):149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Buck Louis GM, Toppari J, Andersson AM. Male reproductive disorders and fertility trends: influences of environment and genetic susceptibility. Physiol Rev. 2016:96(1):55–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elinder CG, Jarup L. Cadmium exposure and health risks: recent findings. AMBIO J Human Environ. 1996:25:370–373. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wise JP, Wise SS, Little JE. The cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of particulate and soluble hexavalent chromium in human lung cells. Mutat Res. 2002:517(1–2):221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Radetski CM, Ferrari B, Cotelle S, Masfaraud JF, Ferard JF. Evaluation of the genotoxic, mutagenic and oxidantstress potentials of municipal solid waste incinerator bottom ash leachates. Sci Total Environ. 2004:333(1–3):209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Skipper A, Sims JN, Yedjou CG, Paul B, Tchounwou PB. Cadmium chloride induces DNA damage and apoptosis of human liver carcinoma cells via oxidative stress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016:13(1):88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang HF, Chang M, Peng TT, Yang Y, Li N, Luo T. Exposure to cadmium impairs sperm functions by reducing CatSper in mice. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017:42(1):44–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Danadevi K, Rozati R, Reddy PP, Grover P. Semen quality of Indian welders occupationally exposed to nickel and chromium. Reprod Toxicol. 2003:17(4):451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alabi OA, Unuigboje MA, Olagoke DO, Adeoluwa YM. Toxicity associated with long term use of aluminum cookware in mice: a systemic, genetic and reproductive perspective. Mutat Res. 2021:861-862:503296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Waalkes MP, Keefer LK, Diwan BA. Induction of proliferative lesions of the uterus, testes, and liver in Swiss mice given repeated injections of sodium arsenate: possible estrogenic mode of action. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000:166(1):24–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarkar M, Chaudhuri GR, Chattopadhyay A, Biswas NM. Effect of sodium arsenite on spermatogenesis, plasma gonadotrophins and testosterone in rats. Asian J Androl. 2003:5(1):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rahinetu OO. Determination of total petroleum hydrocarbons and selected heavy metals in underground water and soil from the vicinity of major filling stations in Abuja. [project thesis]. Nigeria, Baze University, Abuja. 2021. pp. 17–19 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Topham JC. The detection of carcinogen-induced sperm head abnormalities in mice. Mutat Res. 1980:69(1):149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alabi OA, Olukunle OF, Ojo OF, Oke JB, Adebo TC. Comparative study of the reproductive toxicity and modulation of enzyme activities by crude oil-contaminated soil before and after bioremediation. Chemosphere. 2022:299:134352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wyrobek AJ, Gordon LA, Burkhart JG, Francis MW, Kapp RW Jr, Letz G, Malling HV, Topham JC, Whorton MD. An evaluation of the mouse sperm morphology test and other sperm tests in nonhuman mammals. Mutat Res. 1983:115(1):1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jeyendran RS, Schrader SM, Ven HH, Burg J, Perez-Pelaez M, al-Hasani S, Zaneveld LJD. Association of the in-vitro fertilizing capacity of human spermatozoa with sperm morphology as assessed by three classification systems. Hum Reprod. 1986:1(5):305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nikolettos N, Kiipker W, Demirel C, Schopper B, Blasig C, Sturm R, Felberbaum R, Bauer O, Diedrich K, Al-Hasani S. Fertilization potential of spermatozoa with abnormal morphology. Hum Reprod. 1999:14(1):47–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saacke RG. What is a BSE–SFT standards: the relative importance of sperm morphology: an opinion. Proc Soc Theriogenol. 2001:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Loma Linda University, Centre for fertility and IVF . 2021. [Retrieved 2023 September 9]. https://lomalindafertility.com/infertility/men/sperm-morphology/.

- 44. Cooper TG. Cytoplasmic droplets: the good, the bad or just confusing? Hum Reprod. 2005:20(1):9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bruce W, Heddle J. The mutagenicity of 61 agents as determined by the micronucleus, salmonella and sperm abnormality assays. Can J Genet Cytol. 1979:21(3):319–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alabi OA, Bakare AA. Cytogenotoxic effects and reproductive abnormalities induced by e-waste contaminated underground water in mice. Cytologia. 2014:79(3):331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Giri S, Prasad SB, Giri A, Sharma GD. Genotoxic effects of malathion: an organophosphorus insecticide, using three mammalian bioassays in vivo. Mutat Res. 2002:514(1–2):223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bakare AA, Mosuro AA, Osibanjo O. An in vivo evaluation of induction of abnormal sperm morphology in mice by landfill leachates. Mutat Res. 2005:582(1–2):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alabi OA, Esan BE, Sorungbe AA. Genetic, reproductive and Hematological toxicity induced in mice exposed to leachates from petrol, diesel and kerosene dispensing sites. J Health Pollut. 2017:7(16):58–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Menkveld R, Stander FS, Kotze TJ, Kruger TF, Zyl JA. The evaluation of morphological characteristics of human spermatozoa according to stricter criteria. Hum Reprod. 1990:5(5):586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tosti E, Menezo Y. Intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection (IMSI), useful, useless or harmful? J In Vitro Fertiliz Reprod Med Genet. 2012:2(4):24–36. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lewis SE, Aitken RJ. DNA damage to spermatozoa has impacts on fertilization and pregnancy. Cell Tissue Res. 2005:322(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaplan MM. Laboratory tests. In: Schiff L, Schiff ER, editors. Diseases of the liver. 7th ed. Philadephia, PA, USA: JB Lippinocott; 1993. pp. 108–144 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Hjollund NH, Scheike T, Kolstad H, Giwercman A, Henriksen TB, Ernst E, Bonde JP, Olsen J, et al. Inhibin B as a serum marker of spermatogenesis: correlation to differences in sperm concentration and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. A study of 349 Danish men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997:82(12):4059–4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mahmoud AM, Comhaire FH, Depuydt CE. The clinical and biologic significance of serum inhibins in subfertile men. Reprod Toxicol. 1998:12(6):591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weinbauer GF, Nieschlag E. Gonadotrophin control of testicular germ cell development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995:377:55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sharpe RM, McKinnell C, Kivlin C, Fisher JS. Proliferation and functional maturation of Sertoli cells, and their relevance to disorders of testis function in adulthood. Reproduction. 2003:125(6):769–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Abel MH, Baker PJ, Charlton HM, Monteiro A, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K. Spermatogenesis and sertoli cell activity in mice lacking sertoli cell receptors for follicle-stimulating hormone and androgen. Endocrinology. 2008:149(7):3279–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sultan C, Craste de Paulet B, Audran F, Iqbal Y, Ville C. Hormonal evaluation in male infertility. Ann Biol Clin. 1985:43(1):63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Meeker JD, Godfrey-Bailey L, Hauser R. Relationships between serum hormone levels and semen quality among men from an infertility clinic. J Androl. 2007:28(3):15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]