Abstract

Background

Despite being motivated to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors, cancer survivors are still burdened by suboptimal dietary intake and low levels of physical activity.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, barriers to eating a healthy diet and staying physically active, and sources for seeking nutrition advice reported by breast cancer survivors.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

Participants/setting

The study included 315 survivors of breast cancer who were recruited through social media and provided completed responses to an online exploratory survey.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, perceived barriers to healthy eating and physical activity, and sources of nutrition advice were measured.

Statistical analysis

Frequency distribution of nutrition and physical activity behaviors and changes, barriers to healthy eating and physical activity, and sources of nutrition advice were estimated.

Results

About 84.4% of the breast cancer survivors reported at least 1 positive behavior for improving nutrition and physical activity after cancer diagnosis or treatment. Fatigue was the top barrier to both making healthy food choices (72.1%) and staying physically active (65.7%), followed by stress (69.5%) and treatment-related changes in eating habits (eg, change in tastes, loss of appetite, and craving unhealthy food) (31.4% to 48.6%) as barriers to healthy eating, and pain or discomfort (53.7%) as barriers to being physically active. Internet search (74.9%) was the primary source for seeking nutrition advice. Fewer than half reported seeking nutrition advice from health care providers.

Conclusions

Despite making positive changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, breast cancer survivors experience treatment-related barriers to eating a healthy diet and staying physically active. Our results reinforce the need for developing tailored intervention programs and integrating nutrition into oncology care.

Keywords: Nutrition, Physical activity, Lifestyle, Cancer survivors, Barriers

Advances in early detection and treatment have led to a growing population of breast cancer survivors in the United States, estimated to be 3.8 million in 2019.1 However, cancer treatment can pose a number of issues that impact survivors’ ability to maintain a healthy lifestyle, such as changes in taste preference, gastrointestinal discomfort, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression.2–4 Although many cancer survivors are highly motivated to seek information about lifestyle changes to improve their long-term health,5,6 most are still burdened by suboptimal dietary intake7 and low levels of physical activity.8 Prior studies reported that women with breast cancer had low consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and most did not meet the physical activity recommendations for the general population.9,10 The gap between a desire for improved health and poor adherence to nutrition and physical activity guidelines highlights the strong need to identify barriers to breast cancer survivors attaining a healthy lifestyle. In addition, registered dietitian nutritionists who are trained to provide nutrition counseling to cancer patients and survivors are severely understaffed in outpatient oncology clinics across the United States.11 Cancer survivors can use various sources to seek nutrition advice to address treatment-related adverse effects or to improve overall health. The primary sources that cancer survivors use to seek nutrition advice still need to be evaluated.

The primary goals of this study were to assess whether breast cancer survivors improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, barriers they perceive to healthy eating and physical activity, and sources they use to seek nutrition advice. We further explored whether breast cancer survivors who were undergoing treatment report behavior changes, barriers, and sources differently than those who had completed cancer treatment, and whether demographic-, cancer-, or treatment-related factors were associated with nutrition and physical activity behaviors, making positive changes, and seeking nutrition advice.

METHODS

Study and Survey Design

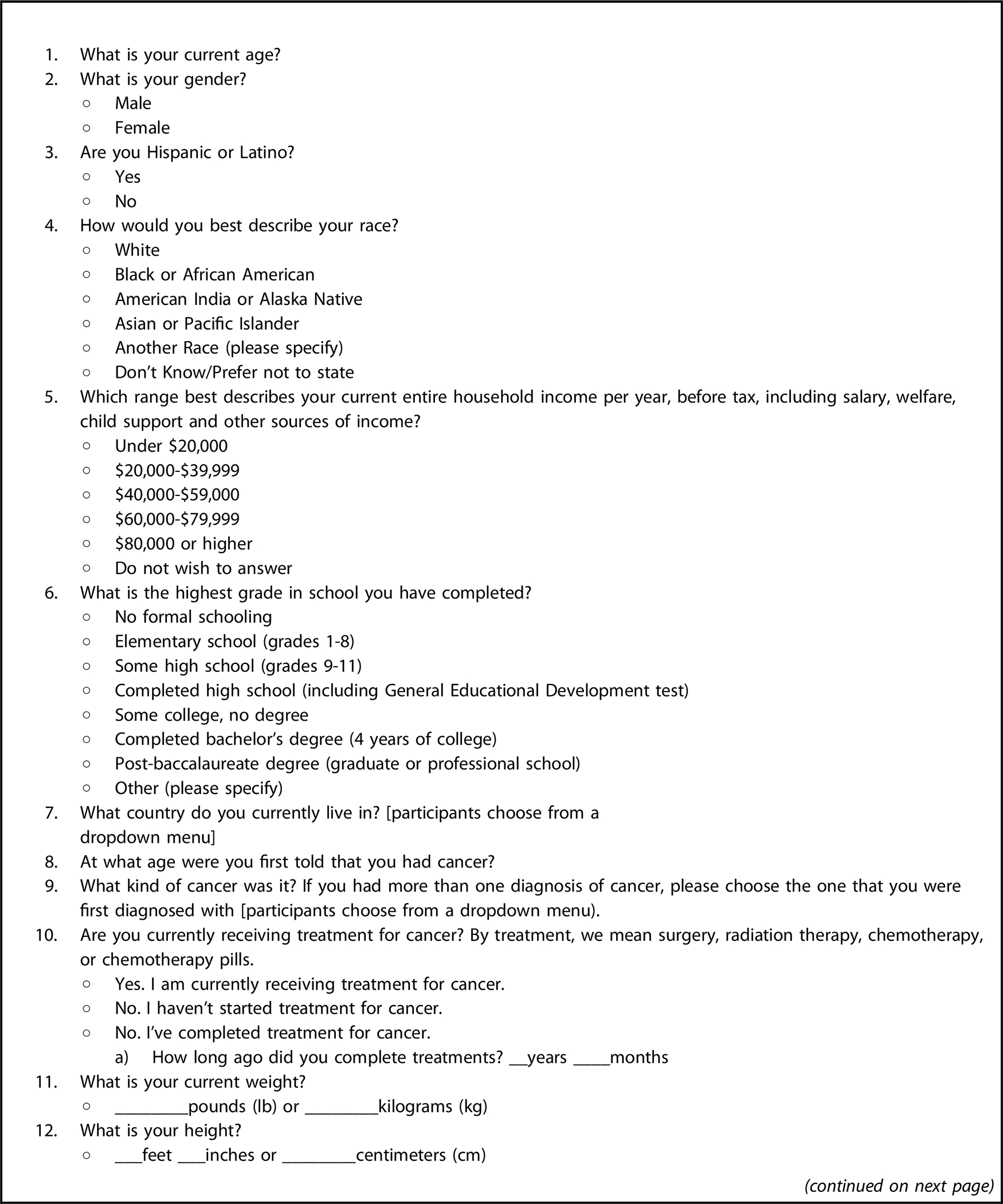

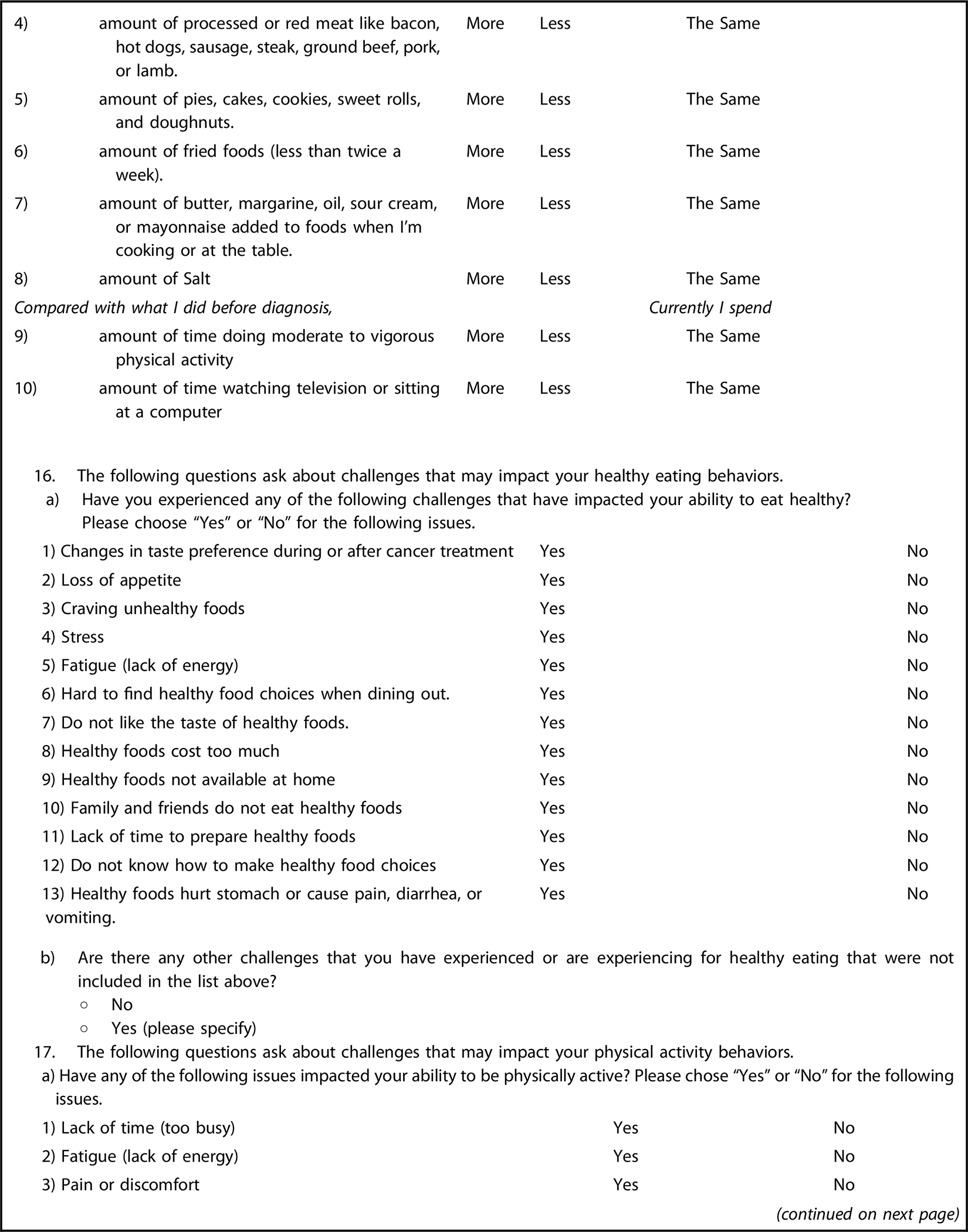

We recruited adult cancer survivors through social media to complete an online survey, the Cancer Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey. Respondents were first asked whether they were 18 years or older, had ever been told bya doctor or other health professional that they had cancer or a malignancy of any kind, and whether they were willing to complete the survey. If the answer to all 3 questions was yes, they could then proceed to completing the survey. The survey asked participants 68 items in the following 5 domains: demographic, cancer diagnosis and treatment, and weight status (12 items); current nutrition and physical activity behaviors (11 items); changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors and weight status after cancer diagnosis or treatment (11 items); perceived barriers to eating a healthy diet and staying physically active (26 items); and sources of nutrition advice (8 items) (Figure 1; available at http://www.jandonline.org). Most survey questions were adapted from existing instruments from various sources and the whole survey took approximately 25 minutes to complete.

Figure 1.

Survey questions in the Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey.

Demographic Characteristics, Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment, and Weight Status.

Participants were asked about their age, gender, race, ethnicity, income, education, country of residence, cancer diagnosis, age at diagnosis, current treatment status (have not started treatment for cancer, currently receiving treatment for cancer, and have completed treatment for cancer), and current weight and height, using questions adapted from the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System survey.12 For those who had completed treatment for cancer, they were also asked how long ago they completed the treatment.

Current Nutrition and Physical Activity Behaviors and Changes after Cancer Diagnosis or Treatment.

Participants were asked their current nutrition and physical activity behaviors, including 8 questions on nutrition behaviors (eating fruits and vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy, and limiting red and processed meats, sweets, fried foods, salty foods, and solid fats added to foods or cooking), 2 questions on physical activity behaviors (getting 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity 5 or more days a week; limiting sedentary behaviors, such as watching television or sitting at the computer), and 1 question on weight management (trying to maintain a healthy weight), adapted from an online Nutrition and Activity Quiz by the American Cancer Society that asks cancer survivors to self-assess their current lifestyle behaviors.13 Participants were also asked whether they eat more, less, or the same amount of these foods; spend more, less, or the same amount of the time in physical activity; and weighed more, less, or the same after cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Perceived barriers to healthy eating and physical activity and sources of nutrition advice.

Participants were also asked whether they experienced (yes vs no) barriers to eating a healthy diet and staying physically active. Questions on perceived barriers were adapted from reported barriers by cancer survivors and the general population from the published literature.14,15 Participants were also asked to report additional barriers that were not included in the list, if any. Survey questions on barriers included those directly related to cancer diagnosis and treatment, such as fatigue, change in taste preference, loss in appetite, gastrointestinal discomfort, pain or discomfort, and reduced physical or mental functioning due to cancer or treatment, as well as general barriers to healthy eating and physical activity, such as healthy foods cost too much, do not belong to a gym or do not have access to equipment or coach, lack of time to prepare healthy foods or exercise, and do not know how to make healthy choices or the best way to exercise. For sources of nutrition advice, participants were asked where they seek nutrition advice from 8 options, including health care providers, family and friends, cancer support groups, books/newspapers/televisions/radios, Internet search such as Google, social media such as Facebook or Twitter, and other sources. These options were adapted from the questions assessing cancer information seeking behaviors among cancer survivors used by the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey.16 Participants could also choose “I do not ask for nutrition advice” if they did not seek nutrition advice.

Survey Administration and Study Population

The survey administration has been described elsewhere.17 Briefly, we identified Twitter accounts of cancer organizations, advocacy groups, and survivors using search terms cancer survivor(s), cancer advocate(s), cancer support, cancer, and cancer nutrition, and performed additional search using Symplur’s Healthcare Social Graph algorithm.18 A total of 301 Twitter accounts were identified using these methods in November and December 2015. We then contacted these Twitter accounts, asking them to promote the survey by providing a link to the survey on their social media platforms (ie, Twitter, Facebook or blogs) for 6 rounds. We also monitored the survey promotion activities of the followers of these Twitter accounts. If any of the followers tweeted the survey link, we subsequently contacted them, asking them to continuously promote the survey until the survey closed. A total of 165 follower accounts were contacted for survey promotion in 4 rounds. Together, these survey promotion activities resulted in 584 responses in 10 weeks from February 9, 2016 to April 19, 2016, among which 29 identified themselves as not having been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had cancer or a malignancy of any kind (ie, not a cancer survivor) and 111 did not provide complete responses (ie, answering at least 85% of the survey questions) and were excluded. A total of 444 cancer survivors provided complete responses to the survey. Because the majority (70.9%) of the survivors were women with breast cancer, we restricted the current analyses to the 315 female breast cancer survivors who provided complete responses to the survey. These included 1 (0.3%) who was waiting for the treatments to start, 110 (34.9%) who were currently receiving the treatments, and 204 (64.8%) who had completed all treatments. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University and granted a waiver of documentation of consent.

Statistical Analyses

We reported the demographic characteristics, cancer and treatment-related characteristics, and current weight status of the cancer survivors who provided completed responses to the survey, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Weight status was determined by calculating body mass index (BMI; calculated as kg/m2) from the self-reported height and weight. Cancer survivors were classified as underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), or obese (≥30). We then calculated the frequency distribution of cancer survivors’ current nutrition and physical activity behaviors, and changes in behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment. We also calculated the frequency distribution of the cancer survivors who experienced barriers to healthy eating and physical activity and used various sources to seek nutrition advice. We conducted these analyses among all cancer survivors. As an exploratory analysis, we compared the frequency distribution among cancer survivors who were currently receiving treatments or waiting to receive treatments (ie, on treatment) and those who had completed all cancer treatments (off treatment) using χ2 tests. Last, we explored whether cancer survivors’ demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and education), cancer and treatment characteristics (treatment status and time since diagnosis), and weight status were associated with having healthy behaviors, making positive changes, and seeking nutrition advice via Internet. Cancer survivors who were underweight and those who had a normal weight were combined into 1 group (BMI < 25) due to the small number of cancer survivors who were underweight. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios and 95% CIs of these factors associated with the outcomes after adjusting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, treatment status, time since diagnosis, and BMI.

All statistical tests were 2-sided and significance was set at an α-level of .05. SAS software19 was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Among the 315 female breast cancer survivors who provided completed responses to the survey, more than 60% were within 5 years post diagnosis at the time of survey completion. Approximately one-third were still receiving cancer treatments or waiting for treatments to start (on treatment), and the remaining two-thirds had completed all cancer treatments (off treatment) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media who completed the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Characteristics | Data |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age at survey completion, y, mean (SDa) | 52.5 (9.7) |

| <45 y | 67 (21.3) |

| 45–54.9 y | 111 (35.4) |

| 55–64.9 y | 100 (31.9) |

| ≥65 y | 36 (11.5) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 275 (87.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9 (2.9) |

| Hispanic | 13 (4.1) |

| Other | 18 (5.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Grades 0–12 | 27 (8.6) |

| High school/some college | 82 (26.2) |

| College graduate or higher | 204 (65.2) |

| Annual household income, n (%) | |

| <$40,000 | 41 (13.0) |

| $40,000–$79,999 | 71 (22.5) |

| ≥$80,000 | 146 (46.4) |

| Missing | 57 (18.1) |

| Country of residence, n (%) | |

| United States | 260 (82.5) |

| Canada | 12 (3.8) |

| United Kingdom | 9 (2.9) |

| Other | 34 (10.8) |

| BMI,b mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.9) |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 11 (3.5) |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9) | 136 (43.3) |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.9) | 98 (31.2) |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30) | 69 (22.0) |

| Age at diagnosis, y, mean (SD) | 47.3 (9.6) |

| Time from diagnosis, y, mean (SD) | 5.3 (5.7) |

| < 5 | 193 (61.5) |

| 5–9 | 79 (25.2) |

| ≥10 | 42 (13.4) |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |

| Waiting for treatments to start | 1 (0.3) |

| Currently receiving treatments | 110 (34.9) |

| Having completed all treatments | 204 (64.8) |

SD = standard deviation.

BMI = body mass index.

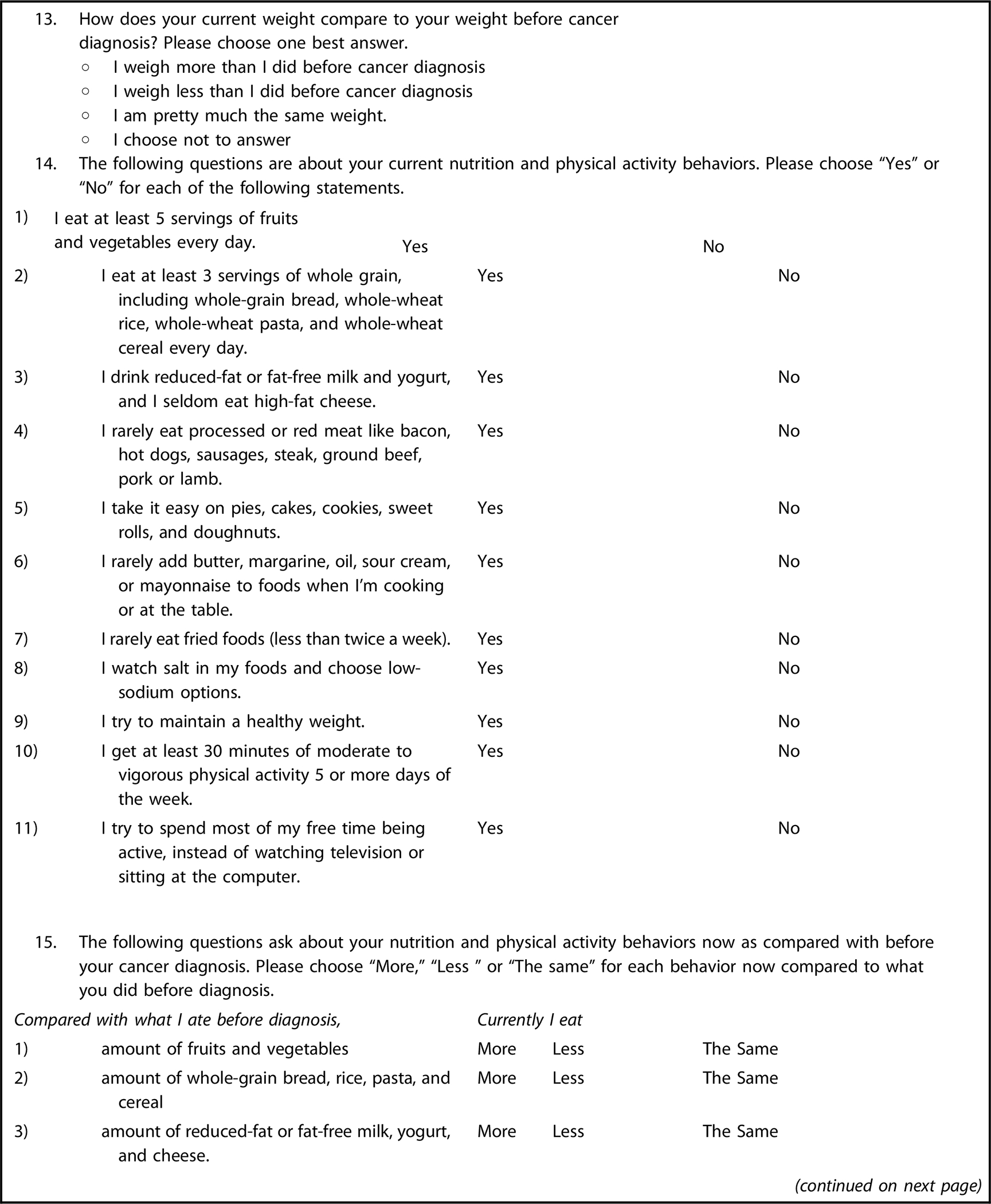

Current Nutrition and Physical Activity Behaviors

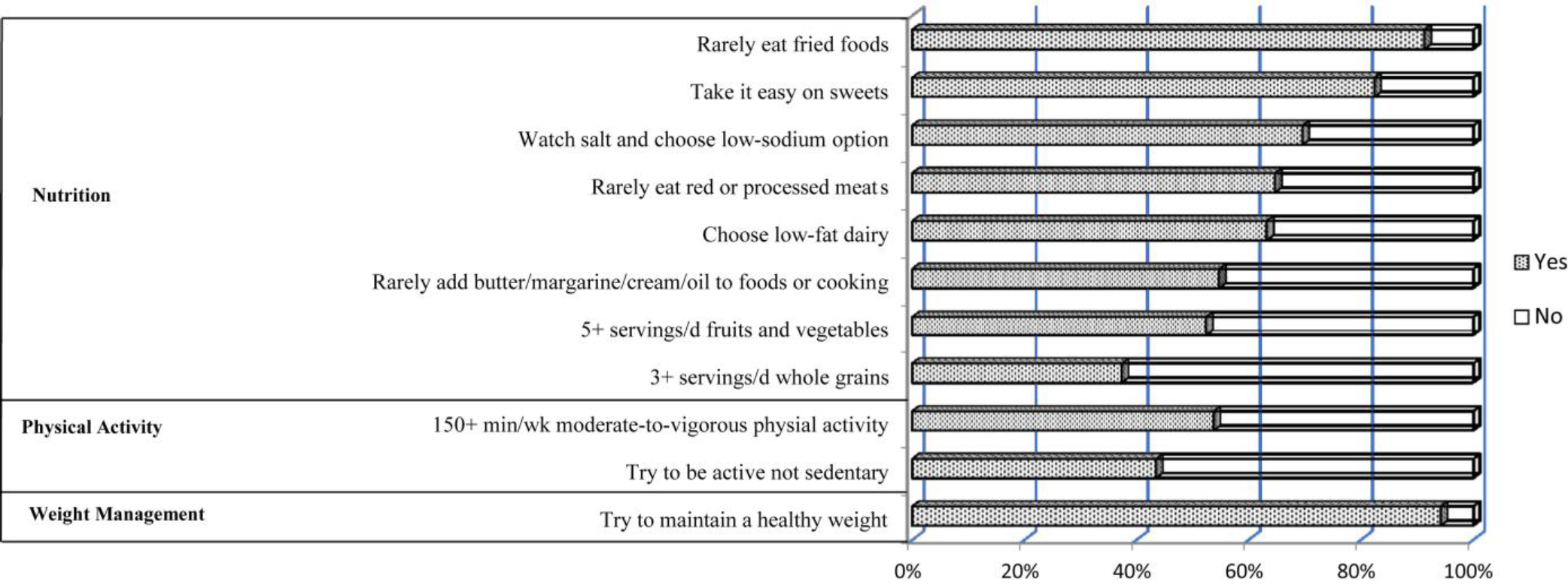

Frequencies of current nutrition and physical activity behaviors ranking from the highest to the lowest frequency of adherence were: trying to maintain a healthy weight (n = 291 [94.2%]); rarely eating fried foods (n = 282 [91.3%]); taking it easy on high-calorie, baked goods such as pies, cakes, cookies, sweet rolls, and doughnuts (n = 254 [82.5%]); watching salt intake and choosing low-sodium options (n = 215 [69.6%]); rarely eating red or processed meat (n = 200 [64.7%]); choosing low-fat dairy (n = 194 [63.2%]); having 150+ minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each week (n = 166 [53.7%]); eating 5+ fruits and vegetables per day (n = 162 [52.4%]); rarely adding solid fats (eg, butter, margarine, oil, sour cream, or mayonnaise) to foods or cooking (n = 169 [54.7%]); trying to be active instead of watching televisions or sitting at the computer (n = 134 [43.4%]); and eating 3+ servings of whole grains per day (n = 115 [37.3%]) (Figure 2). Overall, 46.9% (n = 145) of the breast cancer survivors reported having at least 5 healthy nutrition behaviors, at least 1 healthy physical activity behaviors, and trying to maintain a healthy weight.

Figure 2.

Nutrition and physical activity behaviours reported by 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer survivors Adherence to Recommendations for healthy Eating (CARE) Survey. Shaded bars correspond to percentages of the cancer survivors who reported “yes” to each of the nutrition, physical activity, and weight management behaviors; and unshaded bars correspond to reporting “no” to these behaviors.

Changes in Nutrition and Physical Activity Behaviors after Diagnosis or Treatment

More than one-half of the breast cancer survivors reported positive changes after cancer diagnosis or treatment in 4 nutrition behaviors, including reducing the consumption of red or processed meat, reducing the consumption of high-calorie sweets, reducing the consumption of fried foods, and increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables (Table 2). However, fewer survivors reported reducing solid fats added to foods or cooking, or eating less salt or salty foods. Only one-quarter of the survivors reported increasing the amount of whole-grain bread, rice, pasta, and cereal. For changes in physical activity behaviors, about one-third each reported increasing the amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week, and spending more time staying active and avoiding sedentary behaviors. Overall, 84.4% (n = 266) of the breast cancer survivors reported making at least 1 positive nutrition or physical activity behavioral change after cancer diagnosis or treatment. For weight status, approximately one-third of the breast cancer survivors each reported weighing more, less, or the same after cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Table 2.

Changes in nutrition and activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment reported by 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Self-reported change after cancer diagnosis or treatmenta | Moreb | Lessb | Sameb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n (%) | |||

| Amount of fruits and vegetables | 161 (53.0) | 25 (8.2) | 118 (38.8) |

| Amount of whole-grain bread, rice, pasta, and cereal | 70 (23.0) | 81 (26.6) | 153 (50.3) |

| Amount of reduced-fat or fat-free milk, yogurt, and cheese | 46 (15.2) | 92 (30.5) | 164 (54.3) |

| Amount of red meat or processed meat | 19 (6.3) | 179 (59.3) | 104 (34.4) |

| Amount of high-calorie, baked goods, such as pies, cakes, cookies, sweet rolls, and doughnuts | 20 (6.6) | 179 (58.9) | 105 (34.5) |

| Amount of butter, margarine, oil, sour cream, or mayonnaise added to foods or cooking | 10 (3.3) | 129 (42.6) | 164 (54.1) |

| Amount of fried foods | 9 (3.0) | 165 (54.5) | 129 (42.6) |

| Amount of salt or salty foods | 5 (1.7) | 98 (32.5) | 199 (65.9) |

| Amount of time doing moderate to vigorous physical activity | 109 (35.9) | 102 (33.6) | 93 (30.6) |

| Amount of time watching television or sitting at a computer | 96 (31.6) | 62 (20.4) | 146 (48.0) |

Food and activity items were selected from the online Nutrition and Activity Quiz of the American Cancer Society.13

Participants were asked to report whether they consumed more, less, or the same amount of foods or spent more, less or the same amount of time in physical activity or sedentary behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Perceived Barriers for Attaining Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Behaviors

A large proportion of the breast cancer survivors reported barriers for eating a healthy diet and staying physically active (Table 3). For both nutrition and physical activity behaviors, the most frequently reported barrier was fatigue (72.1% and 65.7%, respectively), followed by stress, depression, or reduced mental functioning as the next frequently reported barrier to healthy eating (69.5%), and pain or discomfort as the next frequently reported barrier to physical activity (53.7%). Cancer survivors also frequently reported treatment-related changes in eating behaviors such as change in taste preference, craving unhealthy foods, and loss of appetite as barriers to eating a healthy diet (31.4%–48.6%). General barriers to healthy eating were reported at lower frequencies (10.8%–34.3%), including high costs of healthy foods; lack of time to prepare for healthy foods; and poor food environment or availability, such as friends and family do not eat healthy foods. Other commonly reported (with >30% reported frequency) barriers to physical activity included no willpower, lack of time, and preferring being sedentary.

Table 3.

Perceived barriers to healthy eating and physical activity reported by 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Perceived barriersa | All breast cancer survivors (n = 315) | Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatmentb (n = 111) | Breast cancer survivors who had completed treatment (n = 204) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Barriers to healthy eating | n (%) | |||

| Fatigue (lack of energy) | 227 (72.1) | 86 (77.5) | 141 (69.1) | 0.11 |

| Stress, depression, or reduced mental function | 219 (69.5) | 81 (73.0) | 138 (67.7) | 0.33 |

| Changes in taste preference during or after cancer treatment | 153 (48.6) | 62 (55.9) | 91 (44.6) | 0.06 |

| Craving unhealthy foods | 134 (42.5) | 50 (45.1) | 84 (41.2) | 0.50 |

| Loss of appetite | 99 (31.4) | 54 (48.7) | 45 (22.1) | <0.0001 |

| Healthy foods cost too much | 96 (30.5) | 36 (32.4) | 60 (29.4) | 0.58 |

| Lack of time to prepare healthy foods | 108 (34.3) | 34 (30.6) | 74 (36.3) | 0.31 |

| Friends and family do not eat healthy foods | 92 (29.2) | 30 (27.0) | 62 (30.4) | 0.53 |

| Hard to find healthy foods when dining out | 93 (29.5) | 38 (34.2) | 55 (27.0) | 0.18 |

| Do not like taste of healthy foods | 46 (14.6) | 18 (16.2) | 28 (13.7) | 0.55 |

| Gastrointestinal discomfort (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) | 34 (10.8) | 19 (17.1) | 15 (7.4) | <0.01 |

| Do not know how to make healthy food choices | 41 (13.0) | 16 (14.4) | 25 (12.3) | 0.59 |

| Healthy foods not available at home | 37 (11.8) | 18 (16.2) | 19 (9.3) | 0.07 |

| Reduced physical functioning due to cancer treatment or other health conditions | 4 (1.3) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.5) | 0.67 |

| Pain | 8 (2.5) | 3 (2.7) | 5 (2.5) | 0.89 |

| Barriers to physical activity | ||||

| Fatigue (lack of energy) | 207 (65.7) | 81 (73.0) | 126 (61.8) | 0.05 |

| Pain or discomfort | 169 (53.7) | 70 (63.1) | 99 (48.5) | 0.01 |

| No willpower | 115 (36.5) | 44 (39.6) | 71 (34.8) | 0.39 |

| Lack of time (too busy) | 112 (35.6) | 31 (27.9) | 81 (39.7) | 0.04 |

| Rather watch television, use computer or tablets, or read | 108 (34.3) | 34 (30.6) | 74 (36.3) | 0.31 |

| Fear of injury | 88 (27.9) | 35 (31.5) | 53 (26.0) | 0.29 |

| Do not enjoy it | 83 (26.4) | 27 (24.3) | 56 (27.5) | 0.55 |

| No one to exercise with | 73 (23.2) | 28 (25.2) | 45 (22.1) | 0.52 |

| Do not belong to gym or have access to equipment or coach | 64 (20.3) | 27 (24.3) | 37 (18.1) | 0.19 |

| Exercise is not a priority | 63 (20.0) | 19 (17.1) | 44 (21.6) | 0.35 |

| Do not know the best way to exercise | 50 (15.9) | 21 (18.9) | 29 (14.2) | 0.28 |

| Reduced physical functioning due to cancer treatment or other health conditions | 26 (8.3) | 6 (5.4) | 20 (9.6) | 0.18 |

| Stress, depression, or reduced mental functioning | 7 (2.2) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (2.0) | 0.67 |

Questions on perceived barriers were adapted from reported barriers by cancer survivors and the general population from the published literature.14,15

Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment included 110 who were currently receiving treatment and 1 who were waiting for treatment to start.

P value corresponded to the comparison between cancer survivors who were undergoing treatment and those who had completed treatment.

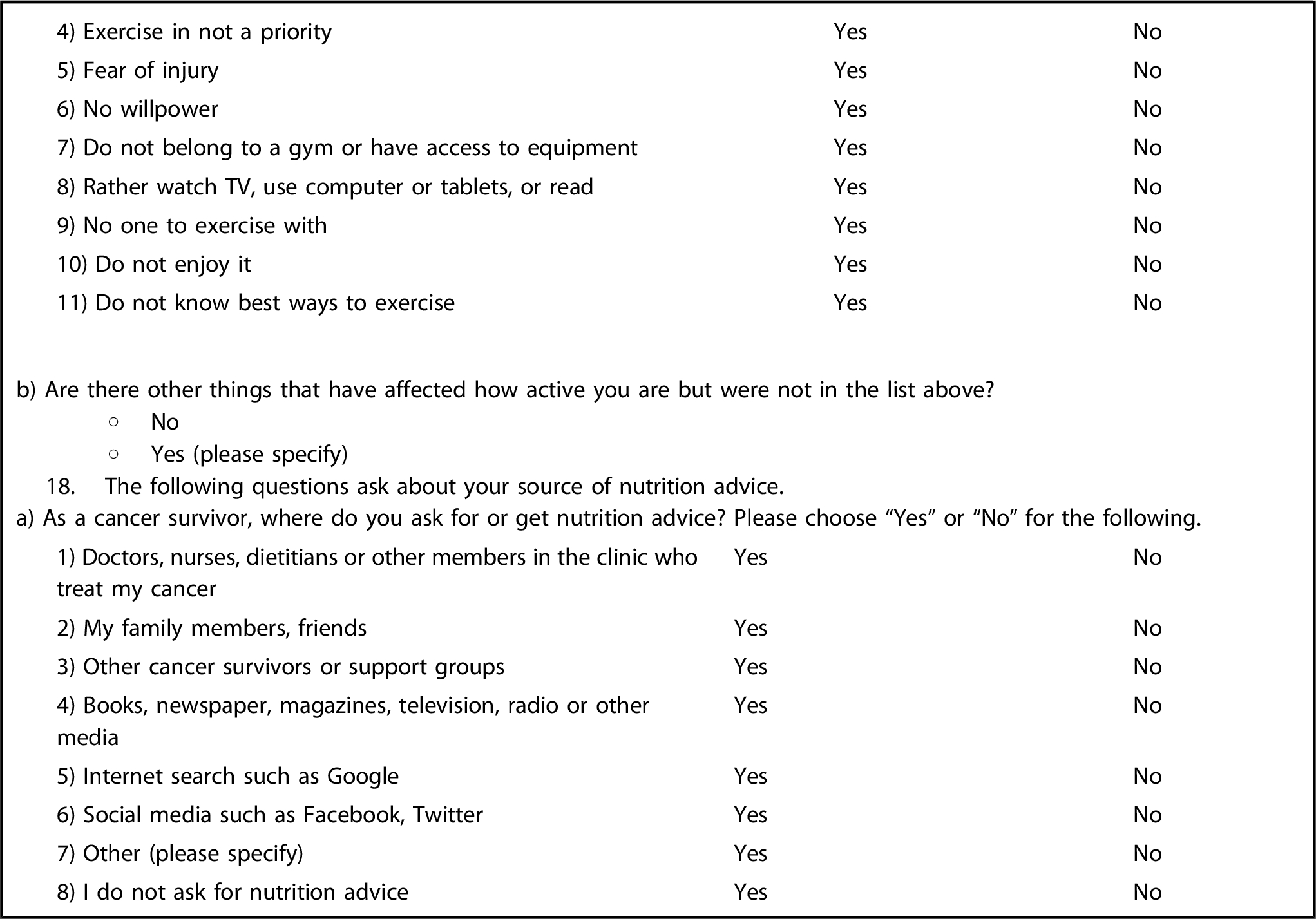

Sources of Nutrition Information

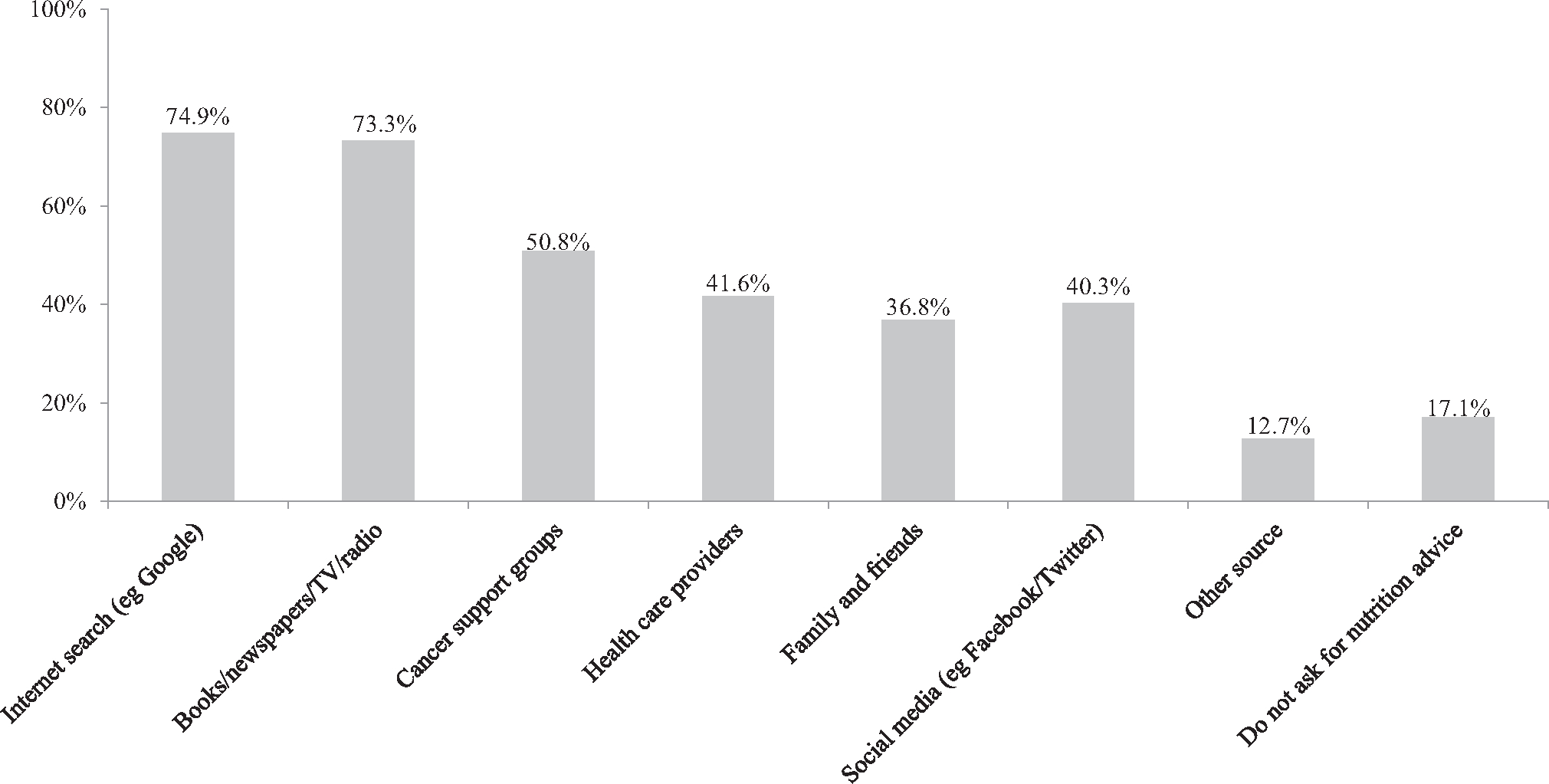

Internet search such as Google (74.9%) was the most frequently reported source from which breast cancer survivors sought nutrition advice, followed by traditional media source, such as books, newspapers, magazines, television and radio, other cancer survivors or support groups, health care providers, family members or friends, social media such as Facebook and Twitter, or other sources (Figure 3). Approximately 17% of the breast cancer survivors did not seek nutrition advice.

Figure 3.

Sources for seeking nutrition advice among 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer survivors Adherence to Recommendations for healthy Eating (CARE) Survey. *Data included in this figure was self-reported. The figures do not total 100% as respondents could select more than one option.

Nutrition and Physical Activity Behaviors, Perceived Barriers, and Sources for Seeking Nutrition Advice by Treatment Status

Breast cancer survivors reported similar nutrition behaviors regardless of treatment status (Table 4; available at www.jandonline.org). However, compared with those who were off treatment, survivors who were on treatment reported a lower frequency of increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity (Table 5; available at www.jandonline.org). For barriers, cancer survivors who were on treatment were significantly more likely to report loss of appetite and gastrointestinal discomfort as barriers to healthy eating, and report fatigue and pain or discomfort as barriers to physical activity (Table 3). Cancer survivors who were on vs off treatment did not differ in sources for seeking nutrition advice except that those who were off treatment were more likely to seek nutrition advice using traditional media such as books, newspapers, television, and radio (Table 6; available at www.jandonline.org).

Table 4.

Frequency of self-reported healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors among 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Self-reported healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviorsa | All breast cancer survivors (n = 315) | Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatmentb (n = 111) | Breast cancer survivors who had completed treatment (n = 204) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Nutrition | n (%) | |||

| I eat 5+ servings/d of vegetables and fruits | 162 (52.4) | 56 (51.9) | 106 (52.7) | 0.88 |

| I eat 3+ servings/d of whole-grain breads, pasta, and cereal | 115 (37.3) | 44 (40.7) | 71 (35.5) | 0.36 |

| I rarely eat red meat or processed meat like bacon, hot dogs, and sausage | 200 (64.7) | 74 (68.5) | 126 (62.7) | 0.31 |

| I choose reduced fat or fat-free milk, yogurt, and cheese | 194 (63.2) | 70 (66.4) | 124 (61.7) | 0.45 |

| I take it easy on high-calorie, baked goods such as pies, cakes, cookies, sweet rolls, and doughnuts | 254 (82.5) | 91 (84.3) | 163 (81.5) | 0.54 |

| I rarely add butter, margarine, oil, sour cream or mayonnaise to foods or cooking | 169 (54.7) | 56 (51.9) | 113 (56.2) | 0.46 |

| I rarely eat fried foods | 282 (91.3) | 98 (90.7) | 184 (91.5) | 0.81 |

| I watch salt and choose low-sodium options | 215 (69.6) | 79 (73.2) | 136 (67.7) | 0.32 |

| Physical activity | ||||

| I get 150+ minu of moderate-to-vigorous physical activities each week | 166 (53.7) | 50 (46.3) | 116 (57.7) | 0.06 |

| I spend most of free time being active, instead of watching television or sitting at the computer | 134 (43.4) | 45 (41.7) | 89 (44.3) | 0.66 |

| Weight management | ||||

| I try to maintain a healthy weight. | 291 (94.2) | 100 (92.6) | 191 (95.0) | 0.38 |

Food and activity items were selected from the online Nutrition and Activity Quiz of the American Cancer Society.13

Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment included 110 who were currently receiving treatment and 1 who were waiting for treatment to start.

P value corresponded to the comparison between breast cancer survivors who were undergoing treatment and those who had completed treatment.

Table 5.

Positive changes in self-reported nutrition and physical activity behaviors among 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Positive Changes in Self-Reported Nutrition and Physical Activity Behaviorsa | All breast cancer survivors (n = 315) | Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatmentb (n = 111) | Breast cancer survivors who had completed treatment (n = 204) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| More | n (%) | |||

| Amount of fruits and vegetables | 161 (53.0) | 52 (49.5) | 109 (54.8) | 0.38 |

| Amount of whole-grain bread, rice, pasta, and cereal | 70 (23.0) | 24 (22.9) | 46 (23.1) | 0.96 |

| Amount of reduced-fat or fat-free milk, yogurt, and cheese | 46 (15.2) | 14 (13.6) | 32 (16.1) | 0.57 |

| Amount of time doing moderate to vigorous physical activity | 109 (35.9) | 28 (26.7) | 81 (40.7) | 0.02 |

| Less | ||||

| Amount of red meat or processed meat | 179 (59.3) | 69 (66.4) | 110 (55.6) | 0.07 |

| Amount of high-calorie, baked goods such as pies, cakes, cookies, sweet rolls and doughnuts | 179 (58.9) | 62 (59.5) | 117 (58.8) | 0.97 |

| Amount of butter, margarine, oil, sour cream, or mayonnaise added to foods or cooking | 129 (42.6) | 42 (40.4) | 87 (43.7) | 0.58 |

| Amount of fried foods | 165 (54.5) | 53 (51.0) | 112 (56.3) | 0.38 |

| Amount of salt or salty foods | 98 (32.5) | 36 (35.0) | 62 (31.2) | 0.50 |

| Amount of time watching television or sitting at a computer | 62 (20.4) | 18 (17.1) | 44 (22.1) | 0.31 |

Food and activity items were selected from the online Nutrition and Activity Quiz of the American Cancer Society.13

Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment included 110 who were currently receiving treatment and 1 who were waiting for treatment to start.

P value corresponded to the comparison between breast cancer survivors who were undergoing treatment and those who had completed treatment.

Table 6.

Sources for seeking nutrition advice reported by 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Sources for seeking nutrition advicea | All breast cancer survivors (n = 315) | Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatmentb (n = 111) | Breast cancer survivors who had completed treatment (n = 204) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | ||||

| Health care providers | 131 (41.6) | 46 (41.4) | 85 (41.7) | 0.97 |

| Family and friends | 116 (36.8) | 41 (36.9) | 75 (36.8) | 0.98 |

| Cancer support groups | 160 (50.8) | 54 (48.7) | 106 (52.0) | 0.57 |

| Books, newspapers, televisions, or radios | 231 (73.3) | 72 (64.9) | 159 (77.9) | 0.01 |

| Internet search such as Google | 236 (74.9) | 82 (73.9) | 154 (75.5) | 0.75 |

| Social media such as Facebook, Twitter | 127 (40.3) | 44 (39.6) | 83 (40.7) | 0.86 |

| Other sources | 40 (12.7) | 13 (11.7) | 27 (13.2) | 0.70 |

| Do not seek nutrition advice | 54 (17.1) | 17 (15.3) | 37 (18.4) | 0.53 |

Survey questions on sources for seeking nutrition advice were adapted from those assessing cancer information seeking behaviors among cancer survivors used by the National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey.16

Breast cancer survivors undergoing treatment included 110 who were currently receiving treatment and 1 who were waiting for treatment to start.

P value corresponded to the comparison between breast cancer survivors who were undergoing treatment and those who had completed treatment.

Factors Associated with Having Healthy Behaviors, Making Positive Changes, and Seeking Nutrition Advice via Internet

Overweight or obese survivors were less likely to report having healthy behaviors compared with those with a healthy weight. Survivors with a higher level of education were more likely to make positive changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors than those with a lower level of education. Survivors who were 5 to 9 years post diagnosis were more likely to report having healthy behaviors or making positive changes compared with those within 5 years post diagnosis. However, survivors who were 10+ years post diagnosis did not differ from those within 5 years post diagnosis in having healthy behaviors, making positive changes, or seeking nutrition advice via Internet. No differences were found by other characteristics, such as age, sex, and race and ethnicity (Table 7; available at www.jandonline. org).

Table 7.

Factors associated with having healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors, making positive changes, and seeking nutrition advice through Internet search reported by 315 breast cancer survivors recruited through social media to complete the online version of the novel Cancer Survivors Adherence to Recommendations for Healthy Eating survey in 2016

| Variable | Having healthy behaviorsa | Making positive changesb | Seeking nutrition advice via Internetc |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| odds ratio (95% CI) d | |||

| Age at survey completion | |||

| <45 y | refe | ref | ref |

| 45–54.9 y | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) |

| 55–64.9 y | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 1.5 (0.5–4.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) |

| ≥65 y | 0.9 (0.3–2.1) | 2.2 (0.4–12.4) | 0.4 (0.2–1.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | ref | ref | ref |

| Other | 1.2 (0.5–2.4) | 1.5 (0.4–5.7) | 1.3 (0.6–3.0) |

| Education | |||

| Grades 0–12 | ref | ref | ref |

| High school/some college | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) | 3.7 (1.0–13.5) | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) |

| College graduate or higher | 1.7 (0.7–4.2) | 2.9 (1.0–9.0) | 0.6 (0.2–2.0) |

| BMI f | |||

| <25 | ref | ref | ref |

| 25–29.9 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) |

| ≥30 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 2.4 (0.7–8.0) | 0.9 (0.5–1.8) |

| Treatment status | |||

| On treatment | ref | ref | ref |

| Off treatment | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 1.8 (0.8–3.9) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

| Time from diagnosis | |||

| <5 y | ref | ref | ref |

| 5–9 y | 1.9 (1.1–3.4) | 3.6 (1.0–12.5) | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) |

| ≥10 y | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 1.1 (0.3–3.6) | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) |

Having healthy behaviors was defined as “yes” if participants reported half or more of healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors asked in the survey (ie, 5+ healthy nutrition behaviors and 1+ healthy physical activity behavior) and trying to maintain a healthy weight, and “no” otherwise.

Making positive changes was defined as “yes” if participants reported making positive changes on any of the nutrition and physical activity behaviors and “no” otherwise.

Seeking nutrition advice via Internet was defined as “yes” if participants reported using Internet search to seek nutrition advice and “no” otherwise.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, education, BMI, treatment status, and time from diagnosis.

ref = reference.

BMI = body mass index; calculated as kg/m2. BMI < 18.5 and BMI 18.5–24.9 were combined into 1 group (BMI < 25) due to the small number of cancer survivors who were underweight (BMI < 18.5).

DISCUSSION

Among breast cancer survivors who responded to an online survey, many reported making positive changes in nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment. However, the proportion of those eating the recommended amount of whole grains and staying physically active remained low. A large proportion of the breast cancer survivors experienced treatment-related factors, including fatigue, stress or depression, taste change, appetite loss, and gastrointestinal discomfort, as barriers to eating a healthy diet, and pain or discomfort as barriers to staying physically active. Internet search was the most frequently used source for seeking nutrition advice.

Despite more than half of the breast cancer survivors reporting that they cut down the consumption of red and processed meat, sweets, and fried foods and increased fruit and vegetable intake, only one-quarter reported increasing whole-grain consumption after cancer diagnosis or treatment. This might reflect an overall low consumption of whole grains in the general US population: 42% of American’s daily calories came from low-quality carbohydrates and only 9% came from high-quality carbohydrates, primarily whole grains.20 We previously reported that cancer survivors’ dietary intake is poor, particularly for whole-grain and dietary fiber intake.7 Whole grain foods are an important component of a healthy plant-based diet for cancer prevention and control.21 Future nutrition interventions for breast cancer survivors need to include a specific focus on increasing whole-grain consumption for improving long-term health outcomes.

Overall, breast cancer survivors reported making fewer positive changes in physical activity than nutrition. This finding corroborates those of other cohorts of cancer survivors.22–24 For example, in 1,527 breast cancer survivors who had participated in a chemotherapy treatment trial, 26.5% of the survivors reported making at least 1 positive dietary change without changing exercise behavior, and only 5% of the survivors reported increasing physical activity without making dietary changes.22 These might imply that breast cancer survivors are less motivated and/or capable of making positive changes in physical activity behaviors. This could be due to the barriers that breast cancer survivors experience for staying physically active as a result of cancer treatment.

Prior literature suggests that cancer treatment can pose immediate adverse effects, such as pain, nausea, fatigue, and anxiety,25,26 resulting in reduced physical, emotional, and social functioning in cancer survivors. Indeed, barriers to healthy eating and physical activity were frequently reported by breast cancer survivors, among which treatment-related barriers were reported at high frequencies. In line with findings from previous studies,27,28 fatigue was reported as the top barrier for both healthy eating and physical activity. In addition, stress or depression, taste change, appetite loss, and gastrointestinal discomfort were reported as common barriers for healthy eating; and pain or discomfort was reported as a common barrier for physical activity. Although breast cancer survivors undergoing cancer treatments reported higher frequencies for specific barriers than those who had completed all treatments, the frequencies remained high for all survivors regardless of treatment status. Thus, to support positive behavior changes, it would be important to tailor the intervention to address fatigue and other common treatment-related barriers experienced by breast cancer survivors across the cancer continuum.

It is interesting to note that breast cancer survivors who were 5 to 9 years post diagnosis reported more positive changes compared with recent survivors (ie, within 5 years of cancer diagnosis), but this pattern did not last into longer survivorship. In fact, breast cancer survivors who were beyond 10 years since diagnosis reported the lowest frequency of healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors. These results suggest that survivors’ motivations for attaining a healthy lifestyle might decline as they become long-term survivors. In addition, overweight/obese survivors were less likely to report healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors, making them an important target for lifestyle interventions.

A national survey reported that up to 72% of the cancer patients received no nutrition advice from their health care providers.29 Thus, it is not surprising that the breast cancer survivors used Internet search as the most common source for seeking nutrition advice. Various cycles of the Health Information National Trends Survey also reported Internet searching as the primary source for accessing cancer-related information among cancer survivors.30,31 Nevertheless, cancer survivors considered health care providers as the most trustworthy source of information31,32 and reported negative experiences when using the Internet for obtaining guidance, such as feeling frustrated during search, taking a lot of efforts to get information, being concerned about information quality, and information being too hard to understand.31,33 This disconnection underscores the needs for integrating nutrition into cancer care in outpatient oncology clinics, such as providers assessing patients’ nutritional status at clinical visits and referring patients to registered dietitian nutritionists for nutrition counseling as part of the treatment plan.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our survey was based on a convenience sample and the respondents were predominantly non-Hispanic White women who are likely to be diagnosed with premenopausal breast cancer (mean age at diagnosis 47.3 years). More than 60% were still within 5 years post diagnosis. This prevents the findings from being generalized to breast cancer survivors in the general population, survivors of other cancer types, or those with different socioeconomic status or racial and ethnic backgrounds. In addition, the survey was promoted through social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, or blogs. Findings might not be extrapolated to breast cancer survivors who are not active or regular users of social media or those who do not have access to Internet or smartphones. Thus, participants were most likely biased toward young survivors who tend to use social media more often than survivors at an older age. Second, most questions asked in our survey were adapted from existing instruments from various sources such as national surveys and published research. However, they have not been evaluated for reliability and validity among cancer survivors and our findings could be subject to measurement errors. Future studies are warranted to further develop and validate instruments assessing cancer survivors’ nutrition and physical activity behaviors, perceived barriers, and nutrition information seeking behaviors. Third, self-reported healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors tend to be overreported.34,35 The high proportion of the breast cancer survivors reporting healthy nutrition and physical activity behaviors and making positive changes needs to be interpreted with caution. Fourth, our survey did not capture information on cancer stage or detailed treatment exposure and, therefore, cannot evaluate the impact of cancer stage or treatment exposure on survivors’ nutrition and physical activity behaviors and perceived barriers.

Despite these limitations, our study provided a comprehensive assessment of various aspects of the nutrition and physical activity behaviors among women with breast cancer who responded to an online survey. Although generalizability of the study findings is limited, attention needs to be brought to the gaps identified: the treatment-related barriers being frequently reported by the survivors and cancer survivors relying on Internet search when seeking nutrition advice. These gaps call for future efforts to provide individualized nutrition counseling to cancer patients as part of the routine oncology care.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite making positive changes in several nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, breast cancer survivors still need to be encouraged to increase whole-grain consumption and avoid sedentary behaviors. They experience frequent treatment-related barriers for eating a healthy diet and staying physically active, and report using Internet search as the primary source for seeking nutrition advice. These findings underscore the needs of developing effective intervention strategies focusing on improving whole-grain consumption and reducing sedentary behaviors after cancer diagnosis and treatment, along with addressing treatment-related barriers frequently experienced by breast cancer survivors. Health care providers also need to play a larger role in providing nutrition care to cancer patients and survivors across the cancer continuum.

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Questions:

Do breast cancer survivors change nutrition and physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment? What are the barriers to eating a healthy diet and being physically active, and sources for seeking nutrition advice reported by breast cancer survivors?

Key Findings:

Despite a high proportion of the breast cancer survivors reporting positive changes in nutrition or physical activity behaviors after cancer diagnosis or treatment, many experienced fatigue, stress, treatment-related changes in eating habits, and pain or discomfort as barriers to healthy eating and physical activity. Internet search was the primary source for seeking nutrition advice.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities 1R01MD011501, Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute P2P Award (5105563) and Tufts Collaborates Grant by Office of the Provost (F.F.Z.). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Laura Keaver, lecturer in Human Nutrition and Dietetics, Department of Health and Nutritional Science, School of Science, Institute of Technology Sligo, Ireland, and a visiting scholar in Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA..

Aisling M. McGough, student, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA..

Mengxi Du, student, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA..

Winnie Chang, student, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA, and Smith College, Northampton, MA..

Virginia Chomitz, assistant professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA..

Jennifer D. Allen, professor, Department of Community Health, Tufts University School of Arts and Sciences, Medford, MA..

Deanna J. Attai, assistant clinical professor, Department of Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles..

Lisa Gualtieri, assistant professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA..

Fang Fang Zhang, professor, Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, Boston, MA..

References

- 1.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boltong A, Keast R. The influence of chemotherapy on taste perception and food hedonics: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(2):152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coa KI, Epstein JB, Ettinger D, et al. The impact of cancer treatment on the diets and food preferences of patients receiving outpatient treatment. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67(2):339–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leak Bryant A, Walton AL, Phillips B. Cancer-related fatigue: Scientific progress has been made in 40 years. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(2):137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeken RJ, Williams K, Wardle J, Croker H. “What about diet?” A qualitative study of cancer survivors’ views on diet and cancer and their sources of information. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;25(5):774–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maschke J, Kruk U, Kastrati K, et al. Nutritional care of cancer patients: A survey on patients’ needs and medical care in reality. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22(1):200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang FF, Liu S, John EM, Must A, Demark-Wahnefried W. Diet quality of cancer survivors and noncancer individuals: Results from a national survey. Cancer. 2015;121(23):4212–4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim RB, Phillips A, Herrick K, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior of cancer survivors and non-cancer individuals: Results from a national survey. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e57598–e57598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, et al. Physical activity levels among breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1484–1491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demark-Wahnefried W, Rock CL. Nutrition-related issues for the breast cancer survivor. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(6):789–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trujillo EB, Claghorn K, Dixon SW, et al. Inadequate nutrition coverage in outpatient cancer centers: Results of a national survey. J Oncol. 2019;2019:7462940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Questionnaire. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/index.htm.

- 13.Nutrition and Physical Activity Quiz. American Cancer Society. Accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.cancer.org/healthy/eat-healthy-get-active/nutrition-activity-quiz.html.

- 14.Arroyave WD, Clipp EC, Miller PE, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ perceived barriers to improving exercise and dietary behaviors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ventura EE, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Barriers to physical activity and healthy eating in young breast cancer survivors: Modifiable risk factors and associations with body mass index. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142(2):423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Information National Trend Survey. Survey instruments. National Cancer Institute. Accessed August 25, 2020, https://hints.cancer.gov/data/survey-instruments.aspx.

- 17.Keaver L, McGough A, Du M, et al. Potential of using Twitter to Recruit cancer survivors and their willingness to participate in nutrition research and web-based interventions: A cross-sectional study. JMIR Cancer. 2019;5(1):e7850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Symplur. The social media analytics platform for healthcare. Accessed May 25, 2020, https://www.symplur.com/.

- 19.SAS [computer program]. Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shan Z, Rehm CD, Rogers G, et al. Trends in dietary carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake and diet quality among US adults, 1999–2016. JAMA. 2019;322(12):1178–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Cancer: A Global Perspective. The Third Expert Report. World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Accessed March 2, 2019. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alfano CM, Day JM, Katz ML, et al. Exercise and dietary change after diagnosis and cancer-related symptoms in long-term survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 79804. Psychooncology. 2009;18(2):128–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humpel N, Magee C, Jones SC. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the health behaviors of cancer survivors and their family and friends. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(6):621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson RE, Neuhouser ML, Hedderson MM, Schwartz SM, Standish LJ, Bowen DJ. Changes in diet, physical activity, and supplement use among adults diagnosed with cancer. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(3):323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochhauser CJ, Lewis M, Kamen BA, Cole PD. Steroid-induced alterations of mood and behavior in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13(12):967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung L, Yanofsky R, Klaassen RJ, et al. Quality of life during active treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(5):1213–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clifford BK, Mizrahi D, Sandler CX, et al. Barriers and facilitators of exercise experienced by cancer survivors: A mixed methods systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(3):685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin-Watt J, Campbell A, Gracey JH. Cancer survivors’ exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: A questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoedjes M, Kruif DA, Mols F, et al. An exploration of needs and preferences for dietary support in colorectal cancer survivors: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2017;12(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finney Rutten LJ, Agunwamba AA, Wilson P, et al. Cancer-related information seeking among cancer survivors: Trends over a decade (2003–2013). J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(2):348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roach AR, Lykins ELB, Gochett CG, Brechting EH, Graue LO, Andrykowski MA. Differences in cancer information-seeking behavior, preferences, and awareness between cancer survivors and healthy controls: A national, population-based survey. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(1):73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou W-YS, Liu B, Post S, Hesse B. Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003e2008. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(3):263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Menon U, et al. Health behaviors in cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(3):643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams SA, Matthews CE, Ebbeling CB, et al. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(4):389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]