Abstract

Objectives

Mesothelioma is an aggressive cancer predominantly affecting the lung and abdominal linings. It can have a unique impact on mental health and well-being (MHWB) due to its incurability, poor prognosis and asbestos-exposure causation. This review’s aims were to identify/synthesise international evidence on mesothelioma’s MHWB impacts; explore MHWB interventions used by patients and carers; and identify evidence of their effectiveness.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

Databases, searched March 2022 and March 2024, were MEDLINE; CINAHL; PsycINFO; Cochrane Library; ASSIA.

Eligibility criteria

We included study designs focusing on psychological impacts of living with mesothelioma and MHWB interventions used by patients and informal carers, published in English since January 2002.

Data extraction and synthesis

A team of reviewers screened included studies using standardised methods. Quality was assessed using validated tools: Mixed-Methods Appraisal tool for primary research and Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews.

Results

Forty-eight studies met the inclusion criteria: 20 qualitative, 16 quantitative, nine reviews, two mixed-methods, one combined systematic review/qualitative study. UK studies predominated. Many MHWB impacts were reported, including traumatic stress, depression, anxiety and guilt. These were influenced by mesothelioma’s causation, communication issues and carer-patient relational interactions. Participants used wide-ranging MHWB interventions, including religious/spiritual practice; talking to mental-health professionals; meaning-making. Some strategies were presented as unhelpful, for example, denial. Participants reported lack of access to support.

Conclusions

Most qualitative studies were rated high quality. The quality of the quantitative studies and reviews varied. The sparse literature regarding MHWB in mesothelioma means more research is needed into impacts on patients and carers, including trauma. To enable access to evidence-based support, research is recommended concerning MHWB interventions’ effectiveness in mesothelioma.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42022302187.

Keywords: systematic review, adult oncology, mental health, respiratory tract tumours, respiratory tract tumours

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study conducted rigorous evaluation of the evidence regarding mental health and well-being impacts and interventions for patients living with mesothelioma and their informal carers.

Gaps in the research literature are identified regarding mental health and well-being impacts including depression and traumatic stress, and the effectiveness of mental health and well-being interventions in mesothelioma.

Due to the scarcity of the relevant literature, all studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included regardless of quality, possibly introducing bias, though quality was used to inform weighting of the different studies in the overall analysis.

Background

Mesothelioma is an aggressive cancer mainly affecting the lining of the lung (pleural), abdominal cavity (peritoneal) and testes, whose only known cause is exposure to asbestos.1 The most common type is malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), with 90 000 global deaths annually.2 Mesothelioma is currently incurable, with a median survival of around 12 months and high symptom-burden.3 Living with incurable cancer is known to entail risk of physical, psychological, social and financial problems for both patients4 and informal caregivers.5 Receiving such a cancer diagnosis may be considered potentially traumatising.5 Uncertainty about their illness in cancer patients is associated with impaired quality of life (QOL).4 The presence of pain has been shown to be strongly associated with depression, anxiety and dissatisfaction with healthcare in cancer patients.3 As well as mesothelioma’s incurable status, other features mean it may cause a unique cluster of impacts on mental health and well-being (MHWB). It has a decades-long latency period and can be difficult to diagnose.2 The prognosis can be very uncertain, with sudden deterioration, and pain can be hard to manage.3 Mesothelioma’s causation is often due to workplace asbestos exposure, so relationships with former employers are part of the psychological context. This context means there are often legal issues involved, such as compensation claims and inquests in the coroner’s court, adding to the stress on patients and families.6 A recent mesothelioma research priority exercise7 identified that the patient and carer experience is under-researched and further investigation is needed into mental health and well-being across the illness journey.

The aim of this systematic literature review was to identify and synthesise current international evidence related to the MHWB impacts of mesothelioma; to explore what interventions are used by patients and their carers living with mesothelioma to support mental health and well-being; and to identify evidence of their effectiveness. We used a broad definition of interventions to encompass informal support and coping strategies as well as professionally provided actions and services. The three most recent reviews concerning the experience of living with mesothelioma and psychosocial aspects were published in 2022.6 8 9 Our searches in March 2024 bring the view of the field up to date. Our review is also the first to scope out MHWB interventions used by patients and carers.

The review questions were as follows:

What is the impact of a diagnosis of mesothelioma on the mental health and well-being of patients and their informal carers?

What strategies and techniques do patients and their informal carers use to manage the impact of living with mesothelioma on their MHWB?

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using narrative data synthesis. This was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

Members of the Mesothelioma UK Research Centre PPI Panel commented on the initial research proposal. They were kept updated with the study’s findings and commented on dissemination plans.

Search strategy

All types of study design focusing on the psychological impact of living with mesothelioma and the psychological interventions used by people living with mesothelioma and their informal carers were included. (Informal carers included partners, family members, friends and neighbours who supported the person living with mesothelioma.) The literature on the psychosocial side of mesothelioma is very sparse.8 We decided to include review articles in our searches as this can provide desirable breadth.10 We hoped to glean further insights from reviewers’ presentations of data, for example, Lond et al’s6 novel use of the term ‘complex trauma’. For the original PROSPERO protocol, see online supplemental information S1.

bmjopen-2023-075071supp001.pdf (106.9KB, pdf)

After team agreement on search terms, the following databases were searched by the University of Sheffield Liaison Librarian for Medicine, Dentistry and Health on 9 March 2022 and repeated 28 March 2024: MEDLINE; CINAHL; PsycINFO; the Cochrane Library and ASSIA. All fields were searched in addition to Medical Subject Headings terms to ensure a thorough approach. The studies were exported into Endnote. The reference lists of papers selected for inclusion were also searched. Literature published in English from January 2002 onwards was included. This start date was chosen as significant numbers of potentially relevant studies had been published in the last 20 years. We wished to include a sufficient but manageable amount, reflecting mesothelioma’s current impact, since treatments and trials have moved on greatly in recent years. Search terms for experience were psycho*/mental*/impact/anxiety/depress*/distress/well-being OR wellbeing. Search terms for interventions were cope/coping/support/adjustment/counselling/antidepressants/therapy/complementary/alternative. The full search strategies for all databases, including search terms and database outputs, are presented in online supplemental information S2.

bmjopen-2023-075071supp002.pdf (26.9KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Qualitative/quantitative/mixed-methods and literature review studies focusing on mental health impacts on patients and informal carers living with mesothelioma.

Qualitative/quantitative/mixed-methods and literature review studies focusing on mental health interventions used by patients and informal carers living with mesothelioma.

Published from January 2002 to March 2024.

Involving adult (≥18 years) humans.

Written in English.

Exclusion criteria

QOL measures as part of clinical trials.

Focused on the epidemiology or biology of mesothelioma.

Results not separated by cancer type, that is, results not presented separately for the mesothelioma patients.

General discussion/commentary/opinion pieces/news articles/book chapters/case reports with no empirical data or without substantial literature review (ie, no method).

Conference proceedings.

Published in a language other than English.

Screening

Titles and abstracts of identified articles were screened by VS. 10% of all titles and abstracts, selected randomly, were independently screened to ensure the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied with good agreement. AMT, CG and SE-M shared this task equally. Disagreement between any two reviewers was discussed and resolved with one of the others.

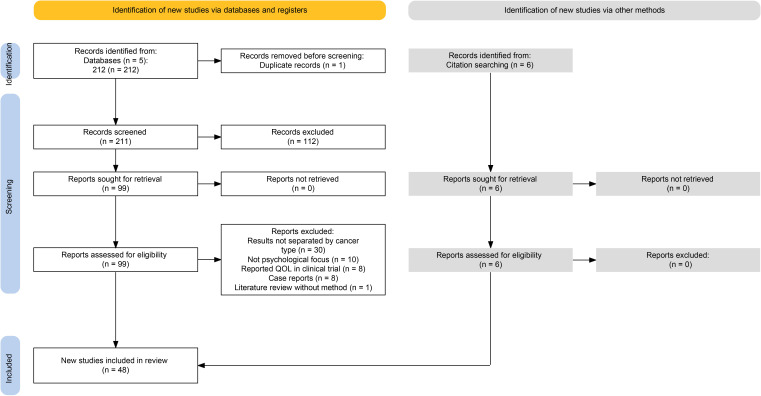

Following title and abstract screening, VS and SE-M independently screened all the full texts. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by either AMT or CG. By using a separate excel spreadsheet, reviewers were blinded to other reviewers’ decisions. Inter-rater reliability was high (Fleiss’ kappa 0.81). The process was documented using a PRISMA diagram (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; QOL, quality of life.

Quality appraisal

Quality assessment was carried out at study level by VS. The Mixed-Methods Appraisal tool11 was used to appraise primary research. This tool presents two screening questions and ratings of five criteria to help users appraise studies’ rationale, design and rigour of data analysis. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses12 was used to appraise literature reviews. This checklist provides 11 questions to help assess methodological quality and the extent to which possibility of bias has been addressed in design, conduct and analysis. A random sample of 10% was checked, half by AMT and half by SH. Disagreements were resolved through discussions with the third reviewer. The results of the assessment informed the weight placed on the findings of different studies in the data synthesis.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction form was completed for all included papers. The main data fields were as follows: (1) publication details (author, journal, year); (2) country; (3) research aim; (4) study design; (5) study population: sampling, inclusion/exclusion criteria; (6) main characteristics of included patients/carers: proportion with mesothelioma, time since diagnosis, age, sex; (7) data collection methods; (8) mental health impact and measurement used, for example, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); (9) mental health intervention used; (10) other key findings presented, for example, effectiveness of intervention and (11) limitations.

Data were extracted to gain an understanding of the following areas:

The prevalence of mental health conditions, defined by a diagnosis, self-reported or MHWB scores.

The self-reported psychological, social and alternative interventions used by people living with mesothelioma and their informal carers.

The effectiveness of mental health interventions used by people living with mesothelioma and their informal carers. For this outcome, the measurement was a reduction in mental health prevalence or severity as measured on a validated scale such as HADS.

VS carried out a narrative synthesis of all extracted data, as there were insufficient data for meta-analysis. This involved developing a preliminary synthesis to initially describe results of included studies; and rigorously comparing and contrasting relationships across the studies, via inductive thematic analysis and concept mapping. VS regularly discussed the process with coresearchers and engaged in reflexive practice to mitigate bias. For example, she utilised reflexive questions such as ‘Am I making assumptions regarding attitudes to denial?’ Results were reported following the PRISMA Checklist for Systematic Reviews (see online supplemental information S3)

bmjopen-2023-075071supp003.pdf (49.7KB, pdf)

Results

The database searches produced 211 articles. On screening titles and abstracts, 112 were excluded. During full-text screening of the remaining 99, 57 were excluded: 30 did not separate their results by cancer type; 10 did not have a psychological focus; eight reported QOL in a clinical trial; eight were case reports13–20 and one was a literature review without method. The reference lists of the remaining articles were checked, leading to six eligible items being added. The total number of eligible articles was 48 (see figure 1).

Summary of included studies

The characteristics of each included study are presented in summary form in table 1 (see online supplemental information S4 for full details). Forty-eight studies met the inclusion criteria. These came predominantly from the UK (24) and Italy (7), with five from Australia, four from Japan, three from the USA and two from the Netherlands. One was based in both the UK and Australia, and one had participants from the UK, France, Italy and Spain. All studies came from high-income countries except one from Brazil, a middle-income country. There were 20 qualitative, 16 quantitative, nine reviews, two mixed-methods and one paper presenting a review plus a qualitative study. Participant numbers totalled: qualitative 320; quantitative 3336 (excluding Henson et al’s21 population-based study); mixed methods 118; reviews 489–7200. The type of mesothelioma researched in the studies was either pleural (21 studies) or all types combined (27); no studies focused on peritoneal mesothelioma.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies’ characteristics

| Authors and year | Country | Study design |

| Arber and Spencer (2013)60 | UK | Qualitative; grounded theory |

| Ball et al (2016)47 | UK | Systematic literature review |

| Bonafede et al (2022)36 | Italy | Prospective, observational study |

| Bonafede et al (2018)48 | Italy | Literature review—qualitative and quantitative studies |

| Bonafede et al (2020)29 | Italy | Quantitative questionnaires |

| Breen et al (2022)8 | Australia | Systematic review with narrative synthesis and quality assessment |

| Clayson et al (2005)59 | UK | Qualitative; semistructured interviews; grounded theory |

| Darlison et al (2014)55 | UK | Survey: questionnaire, 79 option questions plus three open questions |

| Demirjianet al (2024)49 | USA | Cross-sectional psychosocial self-report needs assessment |

| Dooley et al (2010)50 | Australia | Questionnaire |

| Ejegi-Memeh et al (2024)22 | UK | Mixed methods |

| Ejegi-Memeh et al (2022)9 | UK | Rapid systematic review |

| Ejegi-Memeh et al (2021A)53 | UK | Qualitative; semistructured interviews |

| Ejegi-Memeh et al (2021B)44 | UK | Qualitative; semistructured interviews |

| Frissen et al (2021)23 | Netherlands | Qualitative; individual, semistructured interviews |

| Girgis et al (2019)30 | Australia | Qualitative |

| Granieri et al (2013)31 | Italy | Quantitative |

| Guglielmucci et al (2018A)24 | Italy | Study (1): systematic literature review (same data as Bonafede et al (2018)); Study (2): qualitative; thematic analysis |

| Guglielmucci et al (2018B)32 | Italy | Qualitative |

| Harrison et al (2022)37 | UK | Qualitative descriptive |

| Harrison et al (2021)25 | UK | Integrative systematic |

| Henson et al (2019)21 | UK | Quantitative; population-based study |

| Hoon et al (2021)3 | Australia/UK | Multicentre, randomised, non-blinded, parallel group-controlled trial |

| Hughes and Arber (2008)63 | UK | Qualitative |

| Johnson et al (2022)26 | UK | Qualitative |

| Kasai and Hino (2018)51 | Japan | Qualitative design to investigate MPM patientsʼ experiences of transition |

| Lee et al (2022)38 | Australia | Qualitative substudy, secondary analysis of interview data |

| Lehto (2014)58 | USA | Literature review |

| Lond et al (2022)6 | UK | Meta-ethnographic review and synthesis of qualitative literature |

| Maguire et al (2020)52 | UK | Convergent mixed-methods study using patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) plus interviews and focus groups |

| Mercadante et al (2016)46 | Italy | Quantitative; chart review |

| Moore et al (2023)39 | UK, France, Italy, Spain | Cross-sectional questionnaire study (part of larger study) |

| Moore et al (2015)56 | UK | Survey with closed (79) and open (3) questions. This paper focuses on responses to the open questions. |

| Moore et al (2010)57 | UK | Selective literature review; no quality assessment |

| Nagamatsu et al (2022)40 | Japan | Cross-sectional survey, part of larger study on QOL of bereaved family members |

| Nagamatsu et al (2019)64 | Japan | Part of larger quantitative, cross-sectional study. This study analyses answers to two open-ended questions. |

| Nagamatsu et al (2018)66 | Japan | Quantitative; cross-sectional |

| Padilha Baran et al (2019)41 | Brazil | Qualitative; sixteen case studies. Data from family members presented in this paper. |

| Prusak et al (2021)33 | The Netherlands | Qualitative individual semistructured interviews with mesothelioma patients and carers |

| Senek et al (2022)45 | UK | Secondary data analysis of Mesothelioma Outcomes, Research and Experience (MORE) survey |

| Sherborne et al (2024)34 | UK | Mixed methods |

| Sherborne et al (2024A)42 | UK | Qualitative |

| Sherborne et al (2024B)43 | UK | Secondary data analysis plus interviews |

| Sherborne et al (2020)27 | UK | Scoping review |

| Taylor et al (2021)54 | UK | Two-phase service evaluation survey (closed and open-ended questions plus space for comments) |

| Taylor et al (2019)28 | UK | Qualitative; individual and focus group interviews |

| Walker et al (2019)61 | USA | Qualitative; descriptive phenomenological |

| Warby et al (2019)35 | Australia | Quantitative; online surveys for MPM patients and caregivers |

MPM, malignant pleural mesothelioma; QOL, quality of life.

bmjopen-2023-075071supp004.pdf (372KB, pdf)

The recent literature shows increasing nuance, with more papers having a specific focus beyond the broad topic of patients’ lived experience. For example, the perspective of carers has been brought to the fore. Nine studies combined the analysis of patient and carer experiences;8 9 22–28 seven studies analysed experiences of patients and carers and presented these findings separately29–35 and eight studies focused solely on the carers’ experiences and perspectives.36–43 Caregiver burden was assessed for the first time.39

Articles also focused on the following nuanced aspects of living with mesothelioma: gender;44 45 palliative/end-of-life care;23 37 38 46 psychological/psychosocial effects/interventions;8 21–24 27 29 30 33 34 36 40 42 43 47–51 use of information technology;52 effects on a specific employment group;42 43 53 impact of COVID-1954 and long-term survival.26

Quality appraisal

The results of our quality appraisal of the included studies are presented in online supplemental information S5. The majority of the qualitative studies met all the criteria for high quality, showing use of appropriate methods, well substantiated analysis and a coherent approach.

bmjopen-2023-075071supp005.pdf (71.2KB, pdf)

Of the quantitative studies, eight3 21 29 39 40 45 46 49 met all the criteria for high quality. The other quantitative studies generally used relevant sampling, measurement and statistical analysis strategies, but did not address the risk of non-response bias. Two surveys55 56 did not have a clear research question. The majority did not have a representative sample, which may relate to mesothelioma’s rarity and issues with recruiting from a population with high symptom burden. One mixed-methods study52 in its two components reflected this difference in quality between the qualitative and quantitative studies.

The majority of the literature reviews used the term ‘systematic’, though two did not conduct quality appraisal.24 48 Four reviews took other approaches: meta-ethnographic,6 selective,57 scoping27 and unidentified.58 Overall, the review studies had clearly stated questions, with appropriate inclusion criteria, search strategies and synthesis methods. They all used the reported data to make recommendations for policy and/or practice and to specify directives for new research. None of the reviews assessed publication bias where this would have been applicable, and in only three8 9 25 did two or more reviewers carry out independent critical appraisal.

Summary of the narrative data synthesis

We summarised the synthesised data under two main headings: ‘the impact of mesothelioma on MHWB’; and ‘strategies and techniques for managing impacts on MHWB’. The impacts found included shock, anxiety, trauma, frustration and depression. Extra potential for impact was noted from the following factors: mesothelioma’s causation by asbestos exposure; issues concerning the communication of information; and relational interactions between patients and carers/families. The strategies and techniques for managing MHWB impacts included accessing social and spiritual support; finding meaning; gaining a sense of control; and talking to mental health professionals. Some coping strategies were presented in the studies as unhelpful. We also summarised data about the provision of MHWB support and the effectiveness of interventions.

The impact of mesothelioma on mental health and well-being

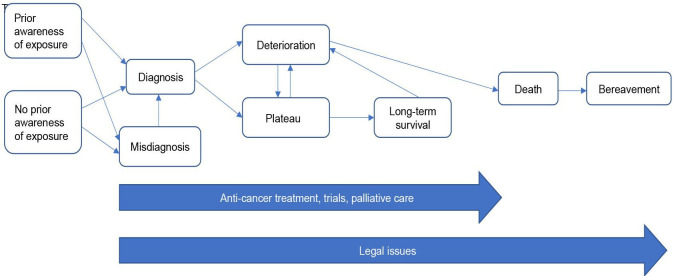

The complex, varied journey of living with mesothelioma for patients and loved ones is shown in figure 2 (Even further complexity is possible in the mesothelioma journey, as for some patients, diagnosis does not occur until a postmortem examination is carried out. Their journey will not therefore map onto this diagram.). The authors developed this schema to conceptualise the mesothelioma pathway’s complexity. Our previous research experience plus a literature review informed its development. Readers can map the review’s results onto it to further visualise where patient and carers may experience MHWB effects, for example, anxiety. All journey stages have potential for MHWB impacts. Mesothelioma’s asbestos causation means impacts can begin long before symptoms arise, due to exposure awareness. There may be MHWB impacts on families/carers after the patient has died, due to financial or legal issues. For example, the legal requirement for an inquest with a postmortem examination may cause great distress. Patients’ and carers’ MHWB impacts may differ at any stage. Here, we present findings on the wide-ranging MHWB impacts experienced and on factors influencing them.

Figure 2.

The complex and varied mesothelioma journey of patients and family carers.

Shock

The shocking effect of receiving a mesothelioma diagnosis was described by many of the articles, with the adjective ‘devastating’ often occurring.6 28 41 44 51 59–61 Of those already aware of asbestos risk, some reacted with resignation,53 59 though others still experienced shock/disbelief.8

Frustration

The journey to diagnosis could itself cause adverse MHWB impact: the often lengthy time created frustration.3 8 41 55 Frustration occurred at other points in the mesothelioma journey, due to treatment delays55 and difficulty with navigating systems37 41 53 and receiving information.62 Disabling symptoms brought frustrating dependency plus isolation.6 27 63 Other frustrating issues included compensation processes6 and exclusion from chemotherapy.64

Anxiety and fear

Most articles highlighted anxiety and fear as MHWB impacts occurring at different points in the mesothelioma journey. Quantitative papers reported anxiety as a common symptom, generally at low severity,3 45 46 though Sherborne et al 34 reported 50% of participants showed possible clinical anxiety. Even prediagnosis, exposure knowledge triggered fear; patients and carers experienced a mortal threat hanging over them, termed ‘Damocles syndrome’, which could be exacerbated when others known to them contracted mesothelioma.6 24 47 Darlison et al 55 showed 20% of participants had worried about getting ill before they were diagnosed.

Uncertainty was a key factor generating anxiety/fear at different stages postdiagnosis, with associated lack of control. As participants had invariably been told the disease was incurable, there was some certainty, yet progression could be unpredictable. Therefore, participants feared their condition degenerating, and when/how they would die.6 8 24 27 34 37 47 48 51 59–61 Prusak et al 33 reported prevalent anxiety about choking to death as the main reason for arranging assisted dying, which is legal in the Netherlands for patients with end-stage disease. Henson et al’s21 finding on suicide that patients with mesothelioma had the highest risk of all English cancer patients may reflect similar fears about a distressing end-of-life stage. The COVID-19 pandemic added extra worries (catching the virus; reduced access to treatment).54

The physical symptoms of mesothelioma caused anxiety/fear for patients and carers, due to their intensity/speed of onset and potential for marking disease progression and end of life.8 27 37 47 50 59 63 Dyspnoea, having strong cognitive and affective components, can escalate anxiety.9 58 Treatment side-effects can be another prevalent source of worry.3 26 The concept of ‘scanxiety’ (about the process/results of clinical tests/imaging) was highlighted for the first time.34

Emotional distress

Most of the included articles reported ‘(emotional) distress’, a catch-all term. This had various triggers throughout the mesothelioma journey: the initial news of the short prognosis;6 27 28 38 44 47 48 61 a message of hopelessness at diagnosis,26 27 37 47 59 reinforced by inappropriate information, for example, an overly precise prognosis.37 47 56 Financial/legal issues provided for some an ongoing source of distress, even after the death.8 35 37 47 63

Medical treatment caused distress at different points in the journey, with negative QOL impact.8 24 48 58 59 Better information about side effects was needed.56 More carers than patients regretted choosing chemotherapy.35 Clinical trials are often the only option for patients with mesothelioma (due to the lack of treatments) and this involvement also had impact on MHWB,26 involving gendered differences.44 For some men, trial participation meant an upsetting loss of control, due to randomisation. The emotional aspect of trial participation was more important for women than for men; the adverse emotional impact on their families could deter women from participating or discourage them from discussing treatment and trial participation.

Medical pathways/communication breakdown also caused distress.28 38 54 Patients and carers reported feeling misunderstood, abandoned and forgotten.33 37 38 54 63 64 Patients and carers often mourned their previous life63 and experienced anticipatory grief.58

Depression and low mood

Eight quantitative studies3 29 40 45 46 49 50 54 plus Sherborne et al’s34 mixed-methods study presented findings on depression/low mood. Good quality studies reported mainly low to moderate levels of depression, though a lesser quality study50 reported a higher level. Bonafede et al 29 identified women as more depressed than men following a diagnosis. COVID-19 may have adversely impacted patient and carer mood.54 Demirjian et al 49 found divorced and Hispanic people were more likely to be depressed. Nagamatsu et al 40 reported higher depression risk for bereaved family members who received no compensation and suffered financially. Depression per se was not discussed in any detail by the included qualitative or review articles. Complicated grief relating to mesothelioma was explored for the first time by Nagamatsu et al:40 complicated grief was more likely for bereaved family members whose loved one had received surgery, who had been impacted financially, who did not receive compensation, and who were dissatisfied with care provided.

Psychological trauma

Several studies reported the presence of traumatic stress symptoms (TSS) (Typical TSS include intrusions, eg, flashbacks and nightmares; avoidance; negative changes to mood and cognition (eg, depression); and altered arousal and reactivity (eg, irritability, disturbed sleep).65 Significant trauma symptoms, correlating with somatic complaints, anxiety, depression and social dysfunction, were mentioned by five reviews,6 8 25 27 58 with TSS linked to physical symptoms reminding patients they would die. Lond et al 6 conceptualised mesothelioma as causing a kind of ‘complex trauma’ (p5). Only three quantitative studies addressed psychological trauma.29 36 50 Dooley et al 50 found patients had symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Bonafede et al 29 found carers were more severely traumatised than patients, with women more traumatised than men. Bonafede et al 36 suggested a strong correlation between degree of engagement in caregiving and severity of indirect TSS. TSS were reported42 43 in carers of military veterans with mesothelioma, linked to moral injury when assumptions about loyalty and good communication were shattered. Sherborne et al’s34 mixed-methods study gave a triangulated view of trauma effects. They found possible PTSD in 33% of participants, with carers scoring higher. The concept of post-traumatic growth relating to mesothelioma was reported for the first time,34 with 35% of participants scoring at a significant level.

Issues concerning causation by asbestos exposure

Mesothelioma’s causation by asbestos exposure added extra potential for MHWB impact. Patients often felt angry, sometimes experiencing conflicted loyalty to former employers.8 24 27 30 43 48 50 58 59 Anger could be redirected towards family or healthcare professionals (HCPs).24 48 Stigmatisation within communities from having mesothelioma could lead to isolation and shame.6 8 32 47

Information needs

Issues concerning the communication of information were a significant factor influencing patients’ and carers’ MHWB, being mentioned by most of the included articles. When information needs were not met, participants experienced negative MHWB impacts. The intensity of each event along the mesothelioma journey depended on HCPs’ communication skills.48 COVID-19 added another complicating factor regarding information-provision: Taylor et al’s54 surveys revealed much confusion regarding the UK shielding policy, which advised certain vulnerable groups to isolate completely from social contact.

Information needs differed among those living with mesothelioma, an important point highlighted in the more recent articles. For example, carers had different information needs from patients, to prepare themselves for end-of-life and afterwards;35 37 38 they wanted to talk with HCPs in private.37 Military veterans with mesothelioma needed information imparting with directness but sensitivity.43 53 Patients who worked in non-asbestos related industries needed targeted advice from ASGs/HCPs to inform them of their financial rights.44

Interaction between patients and families/carers

Another significant factor affecting MHWB, mentioned by most articles, was the relational interaction between patients and families/carers. Some studies reported positive MHWB effects relating to such interactions. Nagamatsu et al’s66 participants scored highly on spending enough time with family and feeling valued. Walker et al 61 showed patients’ heightened appreciation for family relationships, despite less physical contact. Trying to keep fulfilling social and family roles, living ‘normally’, was important for many patients.32 60 However, adapting to physical deterioration could be difficult for patients and carers. Patients experienced negative changes to self-image,60 and caregivers described loss of the person they knew.8 32 43 Those diagnosed preretirement especially showed difficulties adapting to enforced early retirement.33 Patients worried about being a burden, with patients and carers worrying about upsetting others.3 8 26 27 47 60 61 66 Carers could indeed be negatively impacted by caring; they reported being challenged physically and emotionally by care-tasks,8 30 58 with 75% reporting their health had been impacted.39 Within families, there could be mismatched approaches: some found family support irritating as relatives wanted to discuss feelings, whereas others felt isolated when relatives refused to discuss them.6 24 32 50 Relationship changes, including intimacy loss, could be difficult.32 63 The financial burden could also be a problem,50 and the family’s future security often caused ongoing worry for patients,6 24 47 especially for men.44 Some patients felt concerned and/or guilty that their family may also have been asbestos-exposed.6 24 47 48 60 Long-term survivors needed to manage expectations of family/friends, especially young children.26

In the following section, we present the various strategies and techniques used by patients and carers to manage mesothelioma’s MHWB impacts. We also consider the provision of MHWB support for them.

Strategies and techniques for managing impacts on mental health and well-being

Gaining a sense of control

Most of the articles mentioned strategies/techniques used by patients and carers to manage the MHWB impacts of mesothelioma, with a wide range reflecting the illness’s complexity.6 Several strategies involved gaining a sense of control or empowerment. An increased sense of control was brought by trying to stay healthy,59 for example, special diets and complementary/alternative medicine (CAM).6 24 27 48 60 61 Warby et al 35 reported 23% of patients using CAM. Brazilian patients used traditional herbal medicines for symptoms before approaching HCPs.41 It was not however clear from most articles whether CAM was being accessed to aid physical and/or mental health. Exercise and physiotherapy also helped give a sense of control,6 24 27 48 61 with men particularly valuing practical healthy lifestyle support.44 Small everyday activities could help boost MHWB, such as distraction, joking and taking short trips.22

Accessing palliative care also increased control,24 27 48 60 for example, by allowing discussion of anxieties.25 Practical financial strategies (will-writing, seeking compensation) increased patients’ personal agency,6 24 33 37 47 59 61 though risked causing frustration/distress.6 35 Assertiveness in pursuing healthcare options added a sense of control.26 44 61

Finding meaning

Patients and carers tried to meaningfully restructure their traumatic reality.6 36 38 48 59 61 Creative activity helped some participants find meaning in their experience.6 Some participants aimed to make best use of remaining time.25 61 Several studies presented strategies of acceptance/stoicism (reported in patients more than carers)6 27 30 49 51 53 59 and having a fighting spirit.6 8 27 30 51 Patients reported developing new appreciation for the value of life and relationships.8 61 Connection to nature was an important way to promote good MHWB and often involved exercise.22

Social support

Social support was widely mentioned as appreciated by patients and carers, provided by friends, relatives, partners/spouses and neighbours.3 6 33 35 37 44 59 Some participants highlighted the need for non-familial support to avoid burden on the family.37 Many articles reported both patients and carers accessed Asbestos Support Groups (ASGs) to receive information, emotional support and social connection with those having similar experience.3 6 8 24 25 27 30 33 48 51 61 However, some studies noted ASGs did not suit everyone.6 26 37 51 61 Another source of information/emotional support was palliative care and hospice staff; they provided a particular support for carers.22 25 35 Joining asbestos campaign groups helped participants channel and relieve anger.22

Religious and spiritual support

Several studies3 8 22 25 38 41 61 described patients and carers engaging with religious/spiritual communities and practices, which supported their MHWB. They experienced a greater sense of control and hope, with Breen et al 8 finding this applied particularly to carers. A miracle cure provided a focus for hope.41 Spiritual counsellors gave particular attention to supporting families.23

Talking to mental health professionals

For some patients and carers, talking to mental health professionals was important. Seven articles reported participants receiving counselling/talking to psychologists, social workers or caseworkers.3 22 23 27 33 34 63 This helped with family communication strategies and adaptation to inability to work. No details were given in the articles about the modality or duration of talking therapy provided. It appeared the term ‘support group’ did not distinguish between Asbestos Support Groups, led by peers and/or charities offering general support and advice, and psychological therapy groups, run by specialist professionals.

Dysfunctional strategies and techniques

Strategies/techniques for managing MHWB impacts were generally found to be helpful.22 However, several articles reported strategies presented as dysfunctional, including denial,6 24 27 30 32 48 60 substance use,49 disengagement,49 self-blame49 and avoidance,24 27 32 used by women more than men.29 Lond et al 6 reported some participants avoided information-based support due to despair-inducing messaging. Carers sometimes avoided expressing their own emotions to protect relatives, at a cost to their own MHWB.30 33 34

Provision of support for mental health and well-being

Patients and carers reported a lack of support for coping with mesothelioma’s psychological impact, with carers receiving less support and often remaining unaware of availability.22 23 26 57 Darlison et al 55 reported that 31% of participants were not offered any emotional support. Patients were often signposted to support services for advanced lung cancer, despite having unique stressors.23 Some participants felt disillusioned when existential concerns went unaddressed.6 All nursing staff had the potential to help patients find meaning and control.25

There was a difference in psychosocial provision between general hospitals and those providing specialist mesothelioma treatment in the Netherlands. HCPs in centres of expertise paid more attention to MHWB,23 while carers sometimes felt forgotten by HCPs in district general hospitals.33 More gradual integration of palliative care could be beneficial, attending to patients who might get ‘lost’ between treatment and end-of-life.23 Participants suggested more compassionate psychosocial support should be given at home.23 55

Patients and carers may have different views about the ideal timing and amount of support;30 caregivers recognised their distinct support needs.37 Feelings of abandonment arose when HCP contact abruptly ceased. Some carers felt they would have benefited from bereavement support or HCP contact after the death.33 35 37 Bereaved carers recognised that they needed self-care advice/encouragement earlier in the illness journey, including advice on how to handle receiving financial compensation.34

The context in which different types of support are offered may influence its acceptability. Several studies8 30 37 reported carers needing one-to-one support. Two studies29 44 reported on gender differences in support preferences. Women used more coping strategies than men, turning more to social support, problem-solving and religion. Men preferred more practical and non-verbal support and were more open to sharing emotions in single-sex groups. Women preferred more emotional support, particularly in small groups, which helped them feel understood, share experiences and express feelings. Women tended to prefer accessing information online. Ejegi-Memeh et al 53 reported that, for male military veterans, support from other veterans was preferable. Maguire et al 52 found that using an app for patient-reported outcome measures (ASymSmeso) provided reassuring psychological support to patients.

Effectiveness of interventions

Although Ejegi-Memeh et al 22 provided an overview of which MHWB interventions mesothelioma patients and carers found helpful, our searches found zero studies researching the effectiveness of specific interventions for mesothelioma. This is an important gap in the research literature.

Discussion

Our review found many MHWB impacts from mesothelioma which were typical for those diagnosed with incurable cancer, such as anxiety and frustration67 and PTSD.68 Other impacts, such as anger, isolation and shame, were linked to its asbestos causation; these had some overlap with psychological effects of workplace deaths on families.69

The wider psycho-oncology literature suggests that there are four situations where psychosocial distress can occur:70 when people who usually cope well are reacting to diagnosis and life-disruption; when there are persisting late effects of disease/treatment; when people have pre-existing coping difficulties; and when people face existential issues, for example, fear of death. Each of these situations is possible for those living with mesothelioma, and therefore support and interventions need to be tailored to each individual situation. New psychological issues can occur at different stages in the mesothelioma journey (see figure 2). For example, fear of cancer recurrence/progression (FCR) is common, often triggered by scans. Psychological interventions can prepare patients and treat FCR if it becomes debilitating.62 71 This is the case in other advanced cancers, where evidence has shown psychosocial interventions are effective for depression, anxiety and distress related to dying/death, plus for enhancing sense of meaning and preparation for end-of-life.72 73 Services need to be tailor-made rather than one-size-fits-all, to capture nuance and thus meet people’s specific needs.73 This includes assessing if they need/are ready for MHWB intervention; and addressing differences between patients/carers and different types of exposure. Not all distressed patients need professional help; they may prefer to self-manage,70 using the types of strategies we found in our review, such as accessing social support.

In our included articles, information was not provided about the modality/duration of talking therapy accessed. The general term ‘support group’ was often used, without being clearly defined. We surmised this included Asbestos Support Groups (charities providing advice and support) as well as possibly psychotherapy groups. Four articles excluded from our sample (due to being case reports) described the development of psychoanalytic psychotherapy groups for patients and families.13–16 These aimed to create a safe shared space, allowing participants to think through the trauma of living in an asbestos-contaminated place, to give meaning to the changes experienced, identify adaptive coping strategies, lessen stigma and promote resilience. Group psychotherapy has been shown to improve MHWB in advanced cancer patients,74 but its effectiveness in mesothelioma is yet to be evaluated.

Our review found that patients and carers were using many different strategies and techniques to manage the MHWB effects of mesothelioma, including complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Use of CAM, such as homeopathy, is common in cancer patients, with a recent review suggesting an average of 50% using it; motives were wanting to treat/cure cancer and treatment complications, addressing holistic needs, improving health and taking control.65 While CAM can help with MHWB, it can also cause interactions with anticancer treatment; HCPs may lack confidence dealing with CAM.75

Limitations

Due to the anticipated scarcity of literature on this topic, all studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included regardless of quality, which may have introduced bias. However, quality was used to inform weighting of the different studies in the overall analysis.

Our decision to include reviews in our searches meant that multiple participants were counted multiple times. Therefore, certain themes may have been overemphasised and our results should be interpreted with this understanding. Almost all the articles were from high-income, Western countries, providing a potentially narrow view of psychological issues, with resulting epistemic injustice.76 A single researcher carried out data synthesis. However, her reflexive practice plus regular discussion with coauthors helped mitigate bias. Established guidance on conducting narrative synthesis was not used, which we acknowledge as a limitation.77 However, we employed transparent and robust processes to sum up the current state of knowledge regarding our review questions. Only English-language searches were conducted, therefore relevant articles in other languages may have been missed. We were not able to search the grey literature due to resource constraints. Despite these limitations, our rigorous and transparent processes enabled reproducibility.

Clinical implications

This review highlighted the importance of specialist, sensitive assessment of MHWB needs and impacts across the patient journey. We showed the potential consequences of not doing so, such as worsened TSSs and suicide risk. The importance of tailoring information-giving to the individual was made clear, for both patients and carers, and throughout the pathway, not just at diagnosis. Professionals need to understand the importance of sensitive occupational history-taking, due to revisiting the circumstances of asbestos exposure and patients’ possible feelings of anger/guilt. Practising person-centred care for people with serious illness recognises the need for high-quality communication and decision-making plus skilled management of clinical uncertainty and involvement of significant others.78 Family carers have needs which are distinct from those of patients, which should be addressed during the patient’s illness and also during bereavement. Taking a person-centred and relationship-centred approach in caring for patients and families living with mesothelioma would help mitigate the factors we found to be affecting MHWB.

Nurses have an important role in supporting patients and carers to cope with and put strategies in place to manage MHWB, including potentially providing brief psychotherapies.72 79 Specialist mesothelioma nurses prove invaluable throughout the patient journey;26 80 increased provision is required across UK geographical areas.81

Future research

The literature regarding MHWB in mesothelioma patients and their informal carers remains relatively sparse. More research is needed into the MHWB impacts on patients and carers, for example, regarding depression (from the qualitative perspective), traumatic stress and suicidality. It would be valuable to explore how/where mesothelioma patients and carers are accessing information about MHWB impacts and interventions. Positive aspects of living with mesothelioma, such as post-traumatic growth, benefit-finding and closer intimate relationships, have received limited attention; research on these could help HCPs develop a more rounded understanding of the disease’s effects. Further research is warranted into the complex interplay between psychological and physical aspects of mesothelioma’s pain and dyspnoea symptoms. Our review found no studies on the effectiveness of interventions for MHWB in mesothelioma, such as group therapy. Therefore, research evaluating the effectiveness and efficiency of MHWB interventions for mesothelioma is urgently needed, so that patients and carers can receive evidence-based support.

Conclusion

This rigorously conducted study evaluated the evidence regarding MHWB impacts and interventions for those living with mesothelioma. The 48 included studies presented many impacts, such as traumatic stress, anxiety and guilt. A wide variety of interventions were reported to help with MHWB, both those delivered formally by professionals and self-directed strategies. A lack of access to appropriate support was often mentioned by participants. More research is required to enable those living with mesothelioma to access the evidence-based MHWB support they deserve.

Other information

The review protocol may be accessed here: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=302187.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All the authors were involved in the acquisition and/or analysis and interpretation of data, and in drafting the manuscript and/or revising it critically. The authors acknowledge University of Sheffield librarian Anthea Tucker’s expert support.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study conceptualisation and design; data analysis and interpretation; drafting manuscript and critiquing and approving manuscript: VS, SE-M, AMT, BT, SH and CG. Data collection: VS and SE-M. Study guarantor: SE-M.

Funding: This review was funded by Mesothelioma UK Grant Number 2102.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Woolhouse I, Bishop L, Darlison L, et al. British Thoracic society guideline for the investigation and management of malignant pleural Mesothelioma. Thorax 2018;73:i1–30. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore A, Bennett B, Taylor-Stokes G, et al. Malignant pleural Mesothelioma: treatment patterns and humanistic burden of disease in Europe. BMC Cancer 2022;22:693. 10.1186/s12885-022-09750-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoon SN, Lawrie I, Qi C, et al. Symptom burden and unmet needs in malignant pleural Mesothelioma: exploratory analyses from the RESPECT-Meso study. J Palliat Care 2021;36:113–20. 10.1177/0825859720948975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Velasco-Durantez V, Martin-Abreu C, et al. Emotional distress, and illness uncertainty in patients with metastatic cancer: results from the prospective Neoetic_Seom study. Curr Oncol 2022;29:9722–32. 10.3390/curroncol29120763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Opsomer S, Lauwerier E, De Lepeleire J, et al. Resilience in advanced cancer Caregiving. A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Palliat Med 2022;36:44–58. 10.1177/02692163211057749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lond B, Quincey K, Apps L, et al. The experience of living with Mesothelioma: A meta-Ethnographic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Health Psychology 2022;41:343–55. 10.1037/hea0001166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor B, Tod A, Gardiner C, et al. Mesothelioma patient and Carer experience research: A research Prioritisation exercise. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2023;63:S1462-3889(23)00015-7. 10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breen LJ, Huseini T, Same A, et al. Living with Mesothelioma: A systematic review of patient and Caregiver Psychosocial support needs. Patient Educ Couns 2022;105:1904–16. 10.1016/j.pec.2022.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ejegi-Memeh S, Sherborne V, Harrison M, et al. Patients' and informal Carers’ experience of living with Mesothelioma: A systematic rapid review and synthesis of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2022;58:S1462-3889(22)00030-8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robinson KA, Whitlock EP, Oneil ME, et al. Integration of existing systematic reviews into new reviews: identification of guidance needs. Syst Rev 2014;3:1–7:60. 10.1186/2046-4053-3-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI 2018;34:285–91. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Joanna Briggs Institute . The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: checklist for qualitative research. Aust Joanna Briggs Inst 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Borgogno FV, Franzoi IG, Barbasio CP, et al. Massive trauma in a community exposed to asbestos: thinking and dissociation among the inhabitants of Casale Monferrato. Brit J Psychotherapy 2015;31:419–32. 10.1111/bjp.12170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Granieri A. The drive for self-assertion and the reality principle in a patient with malignant pleural Mesothelioma: the history of Giulia. Am J Psychoanal 2017;77:285–94. 10.1057/s11231-017-9099-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Granieri A. Extreme trauma in a polluted area: bonds and relational transformations in an Italian community. Int Forum Psychoanalysis 2016;25:94–103. 10.1080/0803706X.2015.1101488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Granieri A, Borgogno FV, Franzoi IG, et al. Development of a brief psychoanalytic group therapy (BPG) and its application in an asbestos national priority contaminated site. Ann Dell Ist Super Di Sanita 2018;54:160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kozlowski D, Provost SC, Tucker J, et al. Dusted community: Piloting a virtual peer-to-peer support community for people with an asbestos-related diagnosis and their families. J Psychosoc Oncol 2014;32:463–75. 10.1080/07347332.2014.917142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mitchell G. Killing George with kindness--is there such a thing as too much palliative care. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:290, 292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore S, Teehan C, Cornwall A, et al. Hands of time”: the experience of establishing a support group for people affected by Mesothelioma. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008;17:585–92. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ting DY. Certain hope. Patient Educ Couns 2006;61:317–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henson KE, Brock R, Charnock J, et al. Risk of suicide after cancer diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76:51–60. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ejegi-Memeh S, Sherborne V, Mayland C, et al. Mental health and wellbeing in Mesothelioma: A qualitative study exploring what helps the wellbeing of those living with this illness and their informal Carers. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2024;70:S1462-3889(24)00070-X. 10.1016/j.ejon.2024.102572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frissen A, Burgers S, Zwan JM, et al. Experiences of Healthcare professionals with support for Mesothelioma patients and their relatives: identified gaps and improvements for care. Eur J Cancer Care 2021;30:e13509. 10.1111/ecc.13509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guglielmucci F, Bonafede M, Franzoi IG, et al. Research and malignant Mesothelioma: lines of action for clinical psychology. Ann Dell’Istituto Super Di Sanità 2018;54:149–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harrison M, Gardiner C, Taylor B, et al. Understanding the palliative care needs and experiences of people with Mesothelioma and their family Carers: an integrative systematic review. Palliat Med 2021;35:1039–51. 10.1177/02692163211007379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson M, Allmark P, Tod AM. Living beyond expectations: a qualitative study into the experience of long-term survivors with pleural Mesothelioma and their Carers. BMJ Open Respir Res 2022;9:e001252. 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sherborne V, Seymour J, Taylor B, et al. What are the psychological effects of Mesothelioma on patients and their Carers? A Scoping review. Psychooncology 2020;29:1464–73. 10.1002/pon.5454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taylor BH, Warnock C, Tod A. Communication of a Mesothelioma diagnosis: developing recommendations to improve the patient experience. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019;6:e000413. 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bonafede M, Granieri A, Binazzi A, et al. Psychological distress after a diagnosis of malignant Mesothelioma in a group of patients and Caregivers at the National priority contaminated site of Casale Monferrato. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1–15. 10.3390/ijerph17124353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Girgis SSmith A “Ben”Lambert S, et al. It sort of hit me like a baseball bat between the eyes”: a qualitative study of the Psychosocial experiences of Mesothelioma patients and Carers. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:631–8. 10.1007/s00520-018-4357-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Granieri A, Tamburello S, Tamburello A, et al. Quality of life and personality traits in patients with malignant pleural Mesothelioma and their first-degree Caregivers. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2013;9:1193–202. 10.2147/NDT.S48965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guglielmucci F, Franzoi IG, Bonafede M, et al. “"the less I think about it, the better I feel": A thematic analysis of the subjective experience of malignant Mesothelioma patients and their Caregivers”. Front Psychol 2018;9:205. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prusak A, Zwan JM, Aarts MJ, et al. The Psychosocial impact of living with Mesothelioma: experiences and needs of patients and their Carers regarding supportive care. Eur J Cancer Care 2021;30:e13498. 10.1111/ecc.13498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sherborne V, Wood E, Mayland CR, et al. The mental health and well-being implications of a Mesothelioma diagnosis: A mixed methods study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2024;70:S1462-3889(24)00043-7. 10.1016/j.ejon.2024.102545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Warby A, Dhillon HM, Kao S, et al. A survey of patient and Caregiver experience with malignant pleural Mesothelioma. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:4675–86. 10.1007/s00520-019-04760-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bonafede M, Chiorri C, Azzolina D, et al. Preliminary validation of a questionnaire assessing psychological distress in Caregivers of patients with malignant Mesothelioma: Mesothelioma psychological distress tool—Caregivers. Psychooncology 2022;31:122–9. 10.1002/pon.5789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harrison M, Darlison L, Gardiner C. Understanding the experiences of end of life care for patients with Mesothelioma from the perspective of bereaved family Caregivers in the UK: A qualitative analysis. J Palliat Care 2022;37:197–203. 10.1177/08258597221079235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee JT, Mittal DL, Warby A, et al. Dying of Mesothelioma: A qualitative exploration of Caregiver experiences. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022;31:e13627. 10.1111/ecc.13627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Moore A, Bennett B, Taylor-Stokes G, et al. Caregivers of patients with malignant pleural Mesothelioma: who provides care, what care do they provide and what burden do they experience Qual Life Res 2023;32:2587–99. 10.1007/s11136-023-03410-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nagamatsu Y, Sakyo Y, Barroga E, et al. Depression and complicated grief, and associated factors, of bereaved family members of patients who died of malignant pleural Mesothelioma in Japan. J Clin Med 2022;11:3380. 10.3390/jcm11123380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baran FDP, Mercês NNA das, Sarquis LMM, et al. Therapeutic itinerary revealed by the family members of individuals with Mesothelioma: multiple case studies. Texto Contexto - Enferm 2019;28:e20170571. 10.1590/1980-265x-tce-2017-0571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sherborne V, Tod A, Taylor B. Mesothelioma: exploring psychological effects on veterans and their family Caregivers. Cancer Nurs Pract 2024;23. 10.7748/cnp.2023.e1831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sherborne V, Tod A, Taylor B. The psychological effects of Mesothelioma in the UK military context from the Carer’s perspective: A qualitative study. Illness, Crisis & Loss 2024;32:171–91. 10.1177/10541373221122964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ejegi-Memeh S, Robertson S, Taylor B, et al. Gender and the experiences of living with Mesothelioma: A thematic analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2021;52:S1462-3889(21)00072-7. 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Senek M, Robertson S, Darlison L, et al. Malignant pleural Mesothelioma patients’ experience by gender: findings from a cross-sectional UK-national questionnaire. BMJ Open Respir Res 2022;9:e001050. 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mercadante S, Degiovanni D, Casuccio A. Symptom burden in Mesothelioma patients admitted to home palliative care. Curr Med Res Opin 2016;32:1985–8. 10.1080/03007995.2016.1226165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ball H, Moore S, Leary A. A systematic literature review comparing the psychological care needs of patients with Mesothelioma and advanced lung cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;25:62–7. 10.1016/j.ejon.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bonafede M, Ghelli M, Corfiati M, et al. The psychological distress and care needs of Mesothelioma patients and asbestos-exposed subjects: A systematic review of published studies. Am J Ind Med 2018;61:400–12. 10.1002/ajim.22831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Demirjian CC, Saracino RM, Napolitano S, et al. Psychosocial well-being among patients with malignant pleural Mesothelioma. Pall Supp Care 2024;22:57–61. 10.1017/S1478951522001596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dooley JJ, Wilson JP, Anderson VA. Stress and depression of facing death: investigation of psychological symptoms in patients with Mesothelioma. Austral J Psychol 2010;62:160–8. 10.1080/00049530903510757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kasai Y, Hino O. Psychological transition characteristics of patients diagnosed with asbestos-related Mesothelioma. Juntendo Med J 2018;64:114–21. 10.14789/jmj.2018.64.JMJ17-OA09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maguire R, Connaghan J, Arber A, et al. Advanced symptom management system for patients with malignant pleural Mesothelioma (Asymsmeso): mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19180. 10.2196/19180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ejegi-Memeh S, Darlison L, Moylan A, et al. Living with Mesothelioma: A qualitative study of the experiences of male military veterans in the UK. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2021;50:S1462-3889(20)30169-1. 10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Taylor B, Tod A, Gardiner C, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with Mesothelioma and their Carers. Cancer Nurs Pract 2021;20:22–8. 10.7748/cnp.2021.e1773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Darlison L, Mckinley D, Moore S. Findings from the National Mesothelioma experience survey. Cancer Nurs Pract 2014;13:32–8. 10.7748/cnp2014.04.13.3.32.e1063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Moore S, Darlison L, Mckinley D. The experience of care for people affected by Mesothelioma. Cancer Nurs Pract 2015;14:14–20. 10.7748/cnp.14.2.14.e1170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Moore S, Darlison L, Tod AM. Living with Mesothelioma. A literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:458–68. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lehto RH. Pleural Mesothelioma: management updates and nursing initiatives to improve patient care. NRR 2014;4:35. 10.2147/NRR.S44751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Clayson H, Seymour J, Noble B. Mesothelioma from the patient’s perspective. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2005;19:1175–90. 10.1016/j.hoc.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Arber A, Spencer L. It’s all bad news”: the first 3 months following a diagnosis of malignant pleural Mesothelioma. Psychooncology 2013;22:1528–33. 10.1002/pon.3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Walker SL, Crist JD, Shea K, et al. The lived experience of persons with malignant pleural Mesothelioma in the United States. Cancer Nurs 2021;44:E90–8. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tauber NM, O’Toole MS, Dinkel A, et al. Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2899–915. 10.1200/JCO.19.00572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hughes N, Arber A. The lived experience of patients with pleural Mesothelioma. Int J Palliat Nurs 2008;14:66–71. 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.2.28597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nagamatsu Y, Oze I, Aoe K, et al. Physician requests by patients with malignant pleural Mesothelioma in Japan. BMC Cancer 2019;19::383. 10.1186/s12885-019-5591-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: A systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2019;35:33–47. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nagamatsu Y, Oze I, Aoe K, et al. Quality of life of survivors of malignant pleural Mesothelioma in Japan: A cross sectional study. BMC Cancer 2018;18:350. 10.1186/s12885-018-4293-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Newton JC, O’Connor M, Saunders C, et al. Who can I ring? where can I go?” living with advanced cancer whilst navigating the health system: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2022;30:6817–26. 10.1007/s00520-022-07107-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Leano A, Korman MB, Goldberg L, et al. Are we missing PTSD in our patients with cancer? part I. Can Oncol Nurs J 2019;29:141–6. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6516338 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Matthews LR, Quinlan MG, Bohle P. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and prolonged grief disorder in families bereaved by a traumatic workplace death: the need for satisfactory information and support. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:609. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fielding R. Developing a preventive Psycho- oncology for a global context. The International Psycho- oncology society 2018 Sutherland award lecture. Psychooncology 2019;28:1595–600. 10.1002/pon.5139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bergerot CD, Philip EJ, Bergerot PG, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence or progression: what is it and what can we do about it? am Soc Clin Oncol Educ B. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2022;42:1–10. 10.1200/EDBK_100031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rodin G, An E, Shnall J, et al. Psychological interventions for patients with advanced disease: implications for oncology and palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:885–904. 10.1200/JCO.19.00058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Teo I, Krishnan A, Lee GL. Psychosocial interventions for advanced cancer patients: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2019;28:1394–407. 10.1002/pon.5103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy: an effective intervention for improving psychological well-being in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:749–54. 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jones E, Nissen L, McCarthy A, et al. Exploring the use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther 2019;18:1534735419846986. 10.1177/1534735419846986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Carel H, Kidd IJ. Epistemic injustice in Healthcare: a Philosophial analysis. Med Health Care and Philos 2014;17:529–40. 10.1007/s11019-014-9560-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme version. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Giusti A, Nkhoma K, Petrus R, et al. The empirical evidence underpinning the concept and practice of person-centred care for serious illness: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003330. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Malakian A, Mohammed S, Fazelzad R, et al. Nursing, psychotherapy and advanced cancer: A Scoping review. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2022;56:S1462-3889(21)00198-8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gardiner C, Harrison M, Hargreaves S, et al. Clinical nurse specialist role in providing generalist and specialist palliative care: A qualitative study of Mesothelioma clinical nurse specialists. J Adv Nurs 2022;78:2973–82. 10.1111/jan.15277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Henshall C, Davey Z, Walthall H, et al. Recommendations for improving follow-up care for patients with Mesothelioma: a qualitative study comprising documentary analysis, interviews and consultation meetings. BMJ Open 2021;11:e040679. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-075071supp001.pdf (106.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075071supp002.pdf (26.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075071supp003.pdf (49.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075071supp004.pdf (372KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-075071supp005.pdf (71.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.