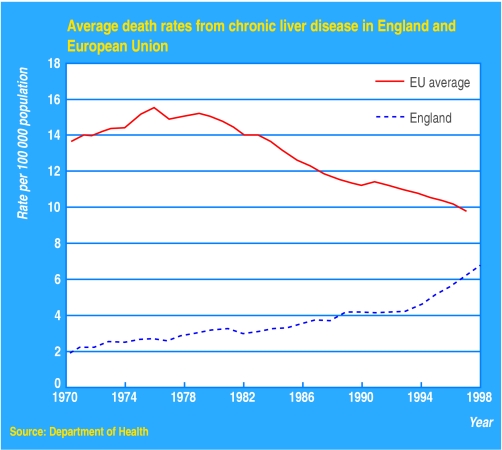

Death rates from cirrhosis of the liver are rising in England whereas rates in most other European Union countries are falling, a government report published last week said.

In 1970 England had a death rate of 2 per 100000 population, seven times lower than the European average at the time. Figures for 1998 show a rate of 7 per 100000 in England, whereas the EU average has declined to below 10 per 100000.

In his first annual report as chief medical officer, Professor Liam Donaldson said that although death rates have risen in all age groups, the largest rise has been in those aged 35 to 44. In this group the rates have increased eightfold in men and almost sevenfold in women since the 1970s. Cirrhosis of the liver now kills more men than Alzheimer's disease and more women than cervical cancer. Last year 1714 women died from liver cirrhosis, 680 more than from cervical cancer.

Higher levels of alcohol consumption, the report said, is “by far the most convincing explanation for the increase in death rates.” Average annual alcohol consumption has risen from around 6 litres of pure alcohol in 1969 to 9.5 litres in 1976 and has since remained at this level. As cirrhosis of the liver takes time to develop, the effects of increased consumption are only now beginning to show.

The report also showed an increase in the number of women drinking above the recommended levels set for weekly consumption, whereas men's drinking habits have remained unchanged. The proportion of women drinking more than 14 units of alcohol was 15% in 1998, compared with 10% in 1988. The report blamed pressure to keep up with men's drinking patterns and heavy advertising of bottled cocktails and sweeter drinks targeted at women.

Professor Donaldson said that it was the pattern of drinking in England that was also to blame for the increased figures. There are “substantial numbers” drinking in a binge drinking pattern, which “is not a feature of other European countries,” he said. He called for “a greater awareness of the long-term damage that alcohol taken in single large amounts can cause.”

The government, the report said, plans to implement a national strategy to tackle alcohol misuse by 2004.

The report also focused on patients with epilepsy, arguing that despite five reports over the past 50 years, services still “remain patchy and fragmented.” This warning follows the recent case of consultant paediatrician Andrew Holton, suspended from Leicester Royal Infirmary after evidence of widespread misdiagnosis and overtreatment of children with epilepsy (8 December, p 1323). New national guidelines on treatment are promised, and the new government modernisation agency will provide advice on how best to redesign the pattern of care for people with epilepsy.

Another subject highlighted in the report was the “deep seated and seemingly intractable problem” of health inequality. Analysis shows that some communities in England have death rates equivalent to the national average in the 1950s. The difference in life expectancy between the socially disadvantaged and the affluent has also widened over the last 10 years, the report added.

Copies of the report are available at www.doh.gov.uk/cmo/ annualreport2001