Short abstract

Mice exposed orally to microspheres showed changes in lipid and other metabolic pathways, and the particles were detected in tissues throughout the body. Changes were greater after exposure to mixed microplastics compared with polystyrene alone.

Every year, manufacturers across the globe produce plastic resins and fibers at a scale of hundreds of millions of metric tons.1 Products made from those materials degrade in the environment into increasingly smaller pieces that humans and animals can ingest or inhale.2 Other plastics are already tiny when they enter the environment, such as microbeads in personal care products that eventually wash down the drain. Microplastics (MPs)—particles of plastic ranging in size from 1 µm to 5 mm—have been detected in both human and animal tissues.3 Although the World Health Organization declared in 2019 that exposures to MPs pose low concerns for human health,4 studies have since observed that these tiny particles have been associated with cellular and biochemical damage in various physiological systems.5–7 With humans estimated to consume up to of MPs per day,8 understanding the physiological effects of these ubiquitous and chronic exposures on health is imperative.

Although myriad studies have documented the physiological effects of MPs on marine organisms,9 fewer studies have examined the same in terrestrial animals.10 Now, a study recently published in Environmental Health Perspectives11 has investigated how ingestion of environmentally relevant concentrations and mixtures of MPs affects the functioning of metabolic pathways within the colon, liver, kidney, and brain in rodents.

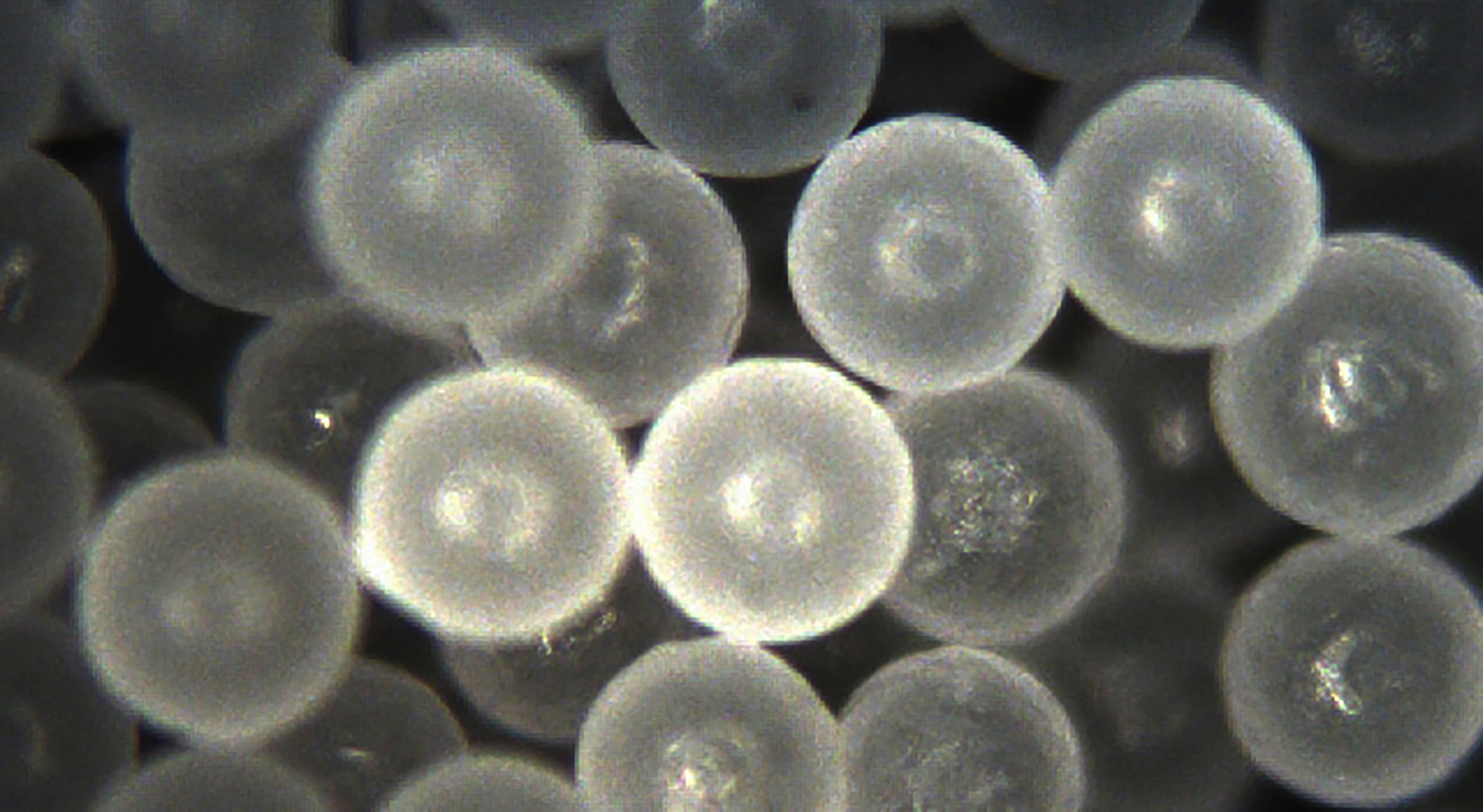

Polyethylene microspheres—a copolymer used in the mixture portion of the study. Image: Courtesy Cospheric LLC.

The research team used oral gastric gavage to expose mice twice weekly for 4 weeks to either polystyrene (PS) microspheres (5 µm in diameter) or a mixture of manufactured microspheres (1–5 µm in diameter)—PS, polyethylene (PE), and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA). PS and PE are frequently detected in the environment12 and commonly added to cosmetic, skin care, and cleansing products.13,14 PLGA is used to encapsulate pharmaceuticals, among other applications.15 Few studies have assessed combinations of different plastic microspheres, according to the authors of the new paper.

The use of manufactured microspheres allowed the researchers to control for size, shape, and composition, and eliminated potential confounding from both other chemicals added during manufacturing and contaminants adsorbed during weathering. However, this is also a limitation, given that real-world microplastics are not uniform in size, shape, or weathering.

In the study, PS or mixed microspheres were given to separate groups of mice at concentrations of 0, 2, or (equivalent to estimated weekly human consumption8), for a total of six groups. The researchers used light microscopy and spectroscopy to analyze serum and tissues from the brain (prefrontal cortex), liver, kidney, and colon for presence of microspheres.

They found that PS and mixed microspheres appeared most abundantly in liver and least in kidney, although both were found in all tissue types as well as in serum; none were detected in samples from the controls. These results suggest the microspheres crossed the gut epithelium, entered the circulatory system, and deposited in different organs, according to the authors.

The team also conducted metabolomics pathway analyses using colon, liver, and brain tissues. All three tissues showed differences related to the type and concentration of metabolites. Some of the most physiologically important differences were observed in metabolic pathways related to lipid metabolism, as well as those involving purines, pyrimidines, and glutamate, which are products of amino acid metabolism; these differences occurred in all three tissue types.

“Alterations in amino acid metabolism have been linked to numerous pathological conditions associated with metabolic and immune diseases,” says Marcus Garcia, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of New Mexico (UNM) Health Sciences Center and first author on the paper. “Highlighting the detection of metabolic biomarkers associated with microplastic exposure is crucial to revealing how microplastics disrupt metabolic pathways, leading to disease. As the data show, alterations can occur in lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and metabolic profiles in the body.”

Phoebe Stapleton, an associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology at Rutgers University, who was not involved in the study, notes, “This was an excellent study to provide insight into the health effects of microplastic exposure, while also highlighting how much work remains in the field. Concentrations within the tissues, biological relevance of these changes, extrapolation to other organ systems, and variations in sex, age, and disease [state] remain to be assessed.”

“This well-designed and -conducted study clearly demonstrated systemic tissue distribution of these particles and associated metabolic disruption,” adds metabolics expert Kun Lu, an associate professor of environmental sciences and engineering at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who also was not involved in the study. He suggests a next step might be to “focus on elucidating molecular mechanisms of metabolic changes induced by microplastics, and how metabolic perturbation leads or contributes to certain disease or endpoints of interest.”

Since the submission of this paper, several groups—including researchers involved in the present study16—have published “eye-opening” data on the presence of microplastics in the human body,17,18 says co-author Matthew Campen, UNM Regents Professor of pharmaceutical sciences. These studies used a powerful new method of pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry that had not been developed in time for the present study.

“The translocation of [microspheres] to organs throughout the body and the observed alterations in metabolomic pathways suggest that microplastics do play a role in potential health risks,” Garcia concludes. “Our findings emphasize the importance of … developing potential regulations to limit plastic pollution and work to protect human health outcomes that may be associated with exposure.”

Biography

Wendee Nicole is an award-winning science writer based in San Diego. She is a regular contributor to Environmental Health Perspectives.

References

- 1.Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. 2017. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv 3(7):e1700782, PMID: 28776036, 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole M, Lindeque P, Halsband C, Galloway TS. 2011. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: a review. Mar Pollut Bull 62(12):2588–2597, PMID: 22001295, 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton AA, Walton A, Spurgeon DJ, Lahive E, Svendsen C. 2017. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci Total Environ 586:127–141, PMID: 28169032, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO (World Health Organization). 22 August 2019. WHO Calls for More Research into Microplastics and Crackdown on Plastic Pollution. https://www.who.int/news/item/22-08-2019-who-calls-for-more-research-into-microplastics-and-a-crackdown-on-plastic-pollution [accessed 18 March 2024].

- 5.Hirt N, Body-Malapel M. 2020. Immunotoxicity and intestinal effects of nano- and microplastics: a review of the literature. Part Fibre Toxicol 17(1):57, PMID: 33183327, 10.1186/s12989-020-00387-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu B, Wu X, Liu S, Wang Z, Chen L. 2019. Size-dependent effects of polystyrene microplastics on cytotoxicity and efflux pump inhibition in human caco-2 cells. Chemosphere 221:333–341, PMID: 30641374, 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng W, Li X, Zhou Y, Yu H, Xie Y, Guo H, et al. 2022. Polystyrene microplastics induce hepatotoxicity and disrupt lipid metabolism in the liver organoids. Sci Total Environ 806(pt 1):150328, PMID: 34571217, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senathirajah K, Attwood S, Bhagwat G, Carbery M, Wilson S, Palanisami T. 2021. Estimation of the mass of microplastics ingested - A pivotal first step towards human health risk assessment. J Hazard Mater 404(pt B):124004, PMID: 33130380, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Chen G, Wang J. 2021. Microplastics in the marine environment: sources, fates, impacts and microbial degradation Toxics 9(2):41, 10.3390/toxics9020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campanale C, Massarelli C, Savino I, Locaputo V, Uricchio VF. 2020. A detailed review study on potential effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(4):1212, 10.3390/ijerph17041212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia MM, Romero AS, Merkley SD, Meyer-Hagen JL, Forbes C, Hayek EE, et al. 2024. In vivo tissue distribution of polystyrene or mixed polymer microspheres and metabolomic analysis after oral exposure in mice. Environ Health Perspect 132(4):47005, PMID: 38598326, 10.1289/EHP13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochman CM, Kross SM, Armstrong JB, Bogan MT, Darling ES, Green SJ, et al. 2015. Scientific evidence supports a ban on microbeads. Environ Sci Technol 49(18):10759–10761, PMID: 26334581, 10.1021/acs.est.5b03909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Baynes A, Renner KO, Zhang M, Scrimshaw MD, Routledge EJ. 2022. Uptake, elimination and effects of cosmetic microbeads on the freshwater gastropod Biomphalaria glabrata. Toxics 10(2):87, 10.3390/toxics10020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scudo A, Liebmann B, Corden C, Tyrer D, Kreissig J, Warwick O. 2017. Intentionally Added Microplastics in Products - Final Report of the Study on Behalf of the European Commission. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327982467_Intentionally_added_microplastics_in_products_-_Final_report_of_the_study_on_behalf_of_the_European_Commission [accessed 15 May 2024].

- 15.Han FY, Thurecht KJ, Whittaker AK, Smith MT. 2016. Bioerodable PLGA-based microparticles for producing sustained-release drug formulations and strategies for improving drug loading. Front Pharmacol 7:185, PMID: 27445821, 10.3389/fphar.2016.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia MA, Liu R, Nihart A, El Hayek E, Castillo E, Barrozo ER, et al. 2024. Quantitation and identification of microplastics accumulation in human placental specimens using pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Toxicol Sci 199(1):81–88, PMID: 38366932, 10.1093/toxsci/kfae021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marfella R, Prattichizzo F, Sardu C, Fulgenzi G, Graciotti L, Spadoni T, et al. 2024. Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 390(10):900–910, PMID: 38446676, 10.1056/NEJMoa2309822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Wang C, Yang Y, Du Z, Li L, Zhang M, et al. 2024. Microplastics in three types of human arteries detected by pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). J Hazard Mater 469:133855, PMID: 38428296, 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.133855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]