A year ago BMJ Publications released a 350 page tome that many people will regard as the last word on informed consent to treatment.1 What is missing from this otherwise comprehensive compendium is a practical guide for clinicians at the coalface. In an effort to overcome this deficit we have generated a menu of alternative styles of informed consent. The first five options relate to consent for treatment within randomised controlled trials, and the final six are options for use in routine clinical practice. We are confident that our menu will help frontline clinicians and patients in practice. It may also help medical ethicists in theory.

Summary points

Many alternative styles of informed consent to treatment exist, along with much theory, a few principles, and different standards of consent within and outside randomised trials, but concise practical advice about the available alternatives is not readily accessible

We have assembled a menu of options to help frontline clinicians and patients to select whichever form of consent meets their particular needs and circumstances

Consent to treatment within randomised controlled trials

Human sacrifice randomised controlled trial consent

“The research ethics committee that approved this trial on your behalf would like you to know that future generations might (or might not) appreciate it if you would put your life at risk by joining this trial. Although we will keep your individual trial results confidential (especially if they run contrary to our hypothesis) and you are free to insist on conventional treatment or withdraw at any time, let's face it—you are a human guinea pig. The investigators responsible for the study may have conducted a systematic review of relevant previous studies to see whether one of the alternative treatments has already been shown to be superior, but this sort of evidence is beyond the interest and competency of our local research ethics committee, which is primarily interested in protecting the host institution from lawsuits should we accidentally kill you along the way. The study results may or may not be submitted for publication, depending on whether they will advance the careers of the investigators and improve the sponsor's market share; but you may be long gone by then anyway.”

Commercial randomised controlled trial for multicentre fun and profit consent

“We would like you to participate in a treatment trial of a new drug. We really don't know much about it because we didn't write the protocol and the trial is being run by a for-profit contract research organisation (since their future business depends on achieving favourable results for their sponsors, we're confident that this trial will turn out the way they want it to). We've joined the study because we will receive a bounty of several thousand dollars for recruiting you into it, plus a big bonus if we can talk a dozen of you into it by the end of the month. The drug we are testing is a trivial (but patentable) modification of a generic drug from the same class. We don't really expect it to perform any better, but we're pulling for ‘non-inferiority’ and a tiny but statistically significant difference in unimportant side effects. We'll be able to use that result in a series of direct to consumer television ads, so that future unsuspecting patients will demand this exorbitantly priced, me-too drug from their physicians. Of course, if the results do not favour the new drug, we will bury them without trace.”

American consent to randomised controlled trial treatment for the 40 million uninsured

“This trial is the only way we can provide health care for uninsured Americans. We promise you free drugs and high quality care during the trial, but may have to abandon you as soon as our grant runs out.”

Randomised controlled trial consent for stockholding investigators

“I own stock in the company that manufactures this treatment, so it must be good. Why else would I have invested so much in the company that manufactures it?”

Kilgore Trout randomised controlled trial consent

“Because we are uncertain about the relative merits of the treatment alternatives for your condition, we suggest that the best option for you is to be treated as a participant in a properly controlled comparison. Because we're deeply concerned about your safety and that of other patients who take part in randomised controlled trials, we subjected the oft heard ‘human guinea pig’ charge to a review of studies that compared the outcomes of patients treated within randomised controlled trials with those of similar patients treated outside such studies.2 To our surprise, the great majority of the evidence shows that patients treated within controlled trials have better outcomes (including mortality). When we included this reassuring information in the proposed informed consent portion of our submission to our local ethics committee, they initially told us that we couldn't give you this information because providing you with the information constituted ‘coercion.’ However, after a public debate in which we accused the ethics committee of unethical behaviour in not bothering even to attempt to overcome their massive ignorance about this evidence, they reversed their decision and now permit us to tell you the truth about what is known.”

Consent to treatment in routine clinical practice

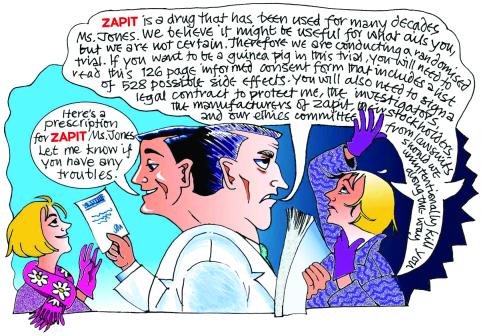

Customary consent

“Here's a prescription, Ms Jones. Let me know if you have any troubles.”

SUE SHARPLES

Alternative forms of standard consent to treatment

The following can be reproduced and attached to the patient's chart: “My colleagues, lawyers, accountants, and I are careful to obtain the consent of all our patients to treatment. After carefully considering your needs, my needs, my financial aspirations (and possibly your preferences), I suggest you consent to treatment X because (tick all that apply):

□ “I was taught this treatment at medical school 30 years ago, and since it's the most time honoured treatment for your condition, it must be the best.”

□ “It's the newest treatment for your condition, so it must be the best.”

(To avoid confusion, we advise that only one of the foregoing reasons is offered to a particular patient about the same treatment.)

□ “It's the most expensive treatment for your condition, so it must be the best. Why else would I have bought so much stock in the company that manufactures it?”

□ “A famous movie star/professional athlete/politician wrote a heart warming endorsement of this treatment in Readers' Digest last year. Indeed, Mrs Reagan's astrologer recommends it.”

□ “I get a kickback from the manufacturer every time I stick one of these gizmos into a patient.”

□ “This drug's manufacturer pays for pizza at our lunchtime conferences, and the pens they distribute are very reliable.”

□ “This drug's manufacturer has given me a hand held computer that's full of all the latest drug prescribing information (they update it on line every month), and it even writes my prescriptions for me. Moreover, I've just learnt that the software they use to update my computer also secretly downloads my prescriptions for the previous month, and I don't want to appear ungrateful by prescribing products made by their competitors.”

□ “Carruthers, who is a member of my lodge, told me that his company makes the kit, and I feel it's only right to support a fellow freemason.”

□ “My medical school/hospital has sold out to the firm that manufactures this drug. They give us huge grants for our research programmes, and we give them first call on any discoveries we make. Their stockholders may vote this money to somebody else if our prescribing behaviour threatens their bottom line.”

□ “I am indebted to the company that makes this drug—not just for first class travel and accommodation at some very enjoyable conference holidays during the conference season but also for paying me huge fees for lecturing about their drugs in a way that minimises their shortcomings and warns against other drugs in their class.”

This is not an exhaustive list of options, but we are confident that it provides readers with a starting point from which they can mix and match and generate additional alternatives.

American emergency consent to treatment

“Before we can operate on you, our lawyers insist that you sign this piece of paper. You may request a magnifying glass to read the fine print. A charge for this will be added to your bill. If you have received narcotics to relieve your pain before signing this form, please indicate this on pages 12, 21, and 54. If you are still in severe pain, you may rip up pages 56 to 75 and chew on page 76. A charge for this will be added to your bill. If you would like to consult a lawyer before signing this form, we have a highly paid staff of lawyers on call who can assist you. Charges for this service are listed on pages 77 to 80. If you would like to know what the evidence is that the procedure will help you, we would be happy to tell you about our excellent experience with patients just like yourself. Fortunately, no one has ever conducted a proper evaluation of this procedure, so our excellent experience is the best available evidence. Trust us. If you would like to question our excellent experience, we would be happy to call a taxi for you. If you are currently unconscious, aphasic, illiterate, unable to communicate in English, or uninsured, please get out of our emergency room at once.”

Cultural imperialism consent to treatment

“I must insist that you tell the patient's family members and the village headman that they must leave the consulting room. They have no part to play here. Although it may be customary for these people to be involved in treatment decisions in your culture, the superior ethical position we have developed in Western culture is that the primacy of the individual is recognised in all things—apart from corporate power, that is. After receiving detailed documents that he or she is unable to read about treatment options and effects, the patient must sign (or make some sort of mark on) the treatment contract. This contract will be unambiguously between the patient and the corporation for which I work. Because the customer is always right, it is important that the patient should shoulder the responsibility for treatment decisions. That way, the patient can take the blame if the treatment doesn't work. If this way of securing consent to treatment is unacceptable in your culture, I am not prepared to enter into the contract. To do so would risk professionally damaging public criticism from ethicists who have made the rules in my culture.”

Patients' rights consent to treatment

“If you expect me, as your patient, to accept the treatment you are prescribing for me, it is only fair that I inform you about my requirements. Firstly, I expect you to have consulted systematic reviews of reliable evidence about the relative merits and demerits of the various treatment alternatives available to me. And don't try telling me that you have decided to ignore that evidence because the people in the research studies weren't very like me. That's an admission that all research is irrelevant because it was all done in the past and all done on other people. I'll only accept a specific argument that the research evidence is clearly irrelevant to me and my circumstances. If you give me a treatment that has been shown to be harmful in a high quality systematic review, I will sue you, even though I am British. If, after considering my needs and preferences, you are uncertain about the relative merits of the treatment options available to me, I expect you to invite me to participate in a randomised comparison. This is because I am aware of the evidence suggesting that people treated within randomised controlled trials do better than others, so that I can hedge my bets in the face of this uncertainty, and to increase the chances that I will benefit from reduced uncertainty in future as a result of the evaluation. None of the foregoing is to suggest that I expect you to behave like an unthinking, insensitive automaton in responding to my request for your help. On the contrary, I expect you to use the clinical skills, judgment, and intangible personal resources that characterise a thoughtful, reflective, evidence based practitioner. But I thought I should make my position clear because I can't abide the arrogance of those doctors who continue to maintain that systematically assembled research evidence is irrelevant to them and their patients.”

Interactive, personalised approach to informed consent

“Good morning Mrs Jones, my name is Dr Smith. Please sit down and make yourself comfortable. Your general practitioner has probably explained to you that he has asked me to see you because your breathlessness doesn't seem to be getting any better, and he wondered whether I might be able to suggest ways of helping. I hope I will be able to do so, but this may well mean seeing you on several occasions over the next few months and working together to find the best treatment for your condition.

“I'm more likely to be able to help if I can get to know more about you and your priorities and preferences. As this is the first time we've met, I thought it might be helpful to mention briefly how I will try to do this. Patients vary in the amount of information that they want to give to and receive from their doctors. Most patients seem to get less information from their doctors than they want, but others would rather not be told some of the things that some doctors assume that they must want to know. Because you and I don't know each other yet, I'm going to need your help in learning how much information you want about your problem, and about the possible treatment options. I'm going to depend on you to prompt me to give you more information if you think I'm not being sufficiently forthcoming, or to tell me that you've heard enough if you think I'm overdoing it. You also need to know that I will never lie in response to a straight question from you, and if I don't know the answer I will do my best to find it for you. Does that seem to you to be an acceptable way of proceeding?”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jan Chalmers, Brian Haynes, and Robert Levine for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: DS has been wined, dined, supported, transported, and paid to speak by countless pharmaceutical firms for over 40 years (see bmj.com).

Potential competing interests for DLS appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Doyal L, Tobias JS, editors. Informed consent in medical research. London: BMJ Publications; 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trout Research and Education Centre. How do the outcomes of patients treated within randomised control trials compare with those of similar patients treated outside these trials? http://hiru.mcmaster.ca/ebm/trout/ (accessed 1 Sep 2001).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.