Abstract

The purpose of this article was to review and summarize the literature investigating the impact of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition. Researchers synthesized data from 10 articles across the following categories: (1) participant characteristics; (2) setting; (3) reinforcement procedures; (4) within-subject replication; (5) results; and (6) secondary measures (e.g., social validity). Results indicated that most of the participants were male, had a diagnosis of autism, and communicated vocally. The differential reinforcement condition in which reinforcement favored independent responses (e.g., edible for independent; praise for prompted responses) was the most frequently employed differential reinforcement condition and it resulted in the acquisition of more responses or faster acquisition for most participants. In addition, when differing reinforcement procedures manipulating different parameters of reinforcements were compared, better outcomes were attained when the schedule of the reinforcer was manipulated within the differential reinforcement procedure relative to when quality or magnitude were manipulated. Limitations of the previous research, recommendations for future research, and implications for clinical practice are discussed.

Keywords: Differential reinforcement, Parameter manipulation, Reinforcer parameters, Skill acquisition

According to Smith (2001), individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may not acquire skills without direct training. Examples of behavioral analytic instructional formats commonly used with persons with ASD include discrete-trial teaching (e.g., Lerman et al., 2016), direct instruction (e.g., Flores & Ganz, 2009), naturalistic teaching (e.g., Alzrayer et al., 2021), and incidental teaching (Delprato, 2001). These teaching procedures include a combination of prompt types (e.g., vocal, model, physical), prompt fading procedures (e.g., least-to-most, most-to-least, progressive delay), and differential consequences for correct (e.g., reinforcement) and incorrect responses (e.g., error correction procedures). Variations within each of these components can affect speed of acquisition (e.g., Seaver & Bourret, 2014). Furthermore, the type of differential reinforcement employed has been shown to differentially affect skill acquisition (e.g., Karsten & Carr, 2009).

Differential reinforcement was defined in Vollmer et al. (2020) as “providing greater reinforcement, along at least one dimension, contingent on the occurrence of one form or type of behavior, while minimizing reinforcement for another form or type of behavior” (p. 1300). Differential reinforcement is often used to reduce problem behavior and increase appropriate, alternative behavior (Vollmer et al., 2020). For example, in a recent systematic review of the published literature on the use of DRA without extinction to reduce problem behavior in individuals with ASD, MacNaul and Neely (2018) identified multiple studies that demonstrated DRA, with or without extinction, successfully decreased problem behavior and increased alternative behavior by manipulating parameters of reinforcement such as quality (e.g., Slocum & Vollmer, 2015) and schedule of reinforcement (e.g., Kelley et al., 2002).

In addition to reducing problem behavior, differential reinforcement has been used to foster acquisition of new skills (e.g., Karsten & Carr, 2009) or decrease prompt dependency (e.g., Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013). A commonly used form of differential reinforcement in skill acquisition programs involves withholding reinforcement following errors while providing appetitive or reinforcing consequences for correct independent and correct prompted responses. However, differential reinforcement can also entail providing high-value reinforcers (e.g., highly preferred item, large quantity of edible) for independent correct responses and lower-value reinforcers (e.g., low to moderately preferred item, small quantity of edible) for prompted correct responses (e.g., Hausman et al., 2014). In this case, reinforcement favors independent correct responses relative to correct prompted responses. The effect of this type of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition is demonstrated by comparing acquisition of novel skills under conditions in which differential reinforcement is or is not in effect or by comparing variations of differential reinforcement procedures. For instance, Karsten and Carr (2009) evaluated the impact of two reinforcement conditions on the skill acquisition of tacts and picture sequencing for two participants with ASD. In the nondifferential reinforcement condition, independent and prompted responses resulted in access to an edible plus praise. In the differential reinforcement condition, independent responses were reinforced with an edible plus praise whereas prompted responses were reinforced with praise only. The results demonstrated that for both participants, skill acquisition occurred more rapidly in the differential reinforcement condition.

Cividini-Motta and Ahearn (2013) implemented similar procedures by comparing the impact of three reinforcement conditions on the acquisition of picture-to-word matching across four individuals with ASD. In the nondifferential reinforcement (i.e., no DR) condition the potent reinforcer (i.e., tokens or edible plus praise) was provided for both independent and prompted responses. In one variation of differential reinforcement (i.e., DR 1 high/mod) the potent reinforcer was delivered contingent on an independent response and a less potent reinforcer (i.e., praise alone) was provided for prompted responses. Finally, in the second differential reinforcement procedure (i.e., DR 2 high/ext), independent responses resulted in access to the potent reinforcer whereas no reinforcers were delivered following prompted responses (extinction). In this study three of the four participants reached the mastery criterion more rapidly in the DR 1 (high/mod) condition, whereas the DR 2 (high/ext) condition was most efficient for the final participant. In the differential reinforcement procedures evaluated by both Karsten and Carr (2009) and Cividini-Motta and Ahearn, the quality of the reinforcer was manipulated. That is, independent responses were reinforced with high-quality reinforcers whereas prompted responses were reinforced with low-quality reinforcers (Vladescu & Kodak, 2010).

Reinforcer parameters other than or in combination with quality can be manipulated to promote skill acquisition. These parameters include reinforcer magnitude (e.g., Fiske et al., 2014), schedule of reinforcer delivery (e.g., Hausman et al., 2014), and immediacy of the delivery of reinforcers. Across these parameters, independent responses are reinforced with high-magnitude reinforcers, on a denser schedule of reinforcement, or more immediately than prompted responses; these result in low-magnitude reinforcers, a leaner schedule of reinforcement, or delayed reinforcer delivery contingent on prompted responses (Vladescu & Kodak, 2010). For example, Johnson et al. (2017) explored the effects of multiple parameters of reinforcement by comparing differential reinforcement iterations in which quality, magnitude, or schedule were manipulated. Results indicated quality was the most efficient parameter for all participants. However, the most effective parameter varied across participants when new skill-types were introduced. Furthermore, studies have also evaluated whether the onset of the implementation of differential reinforcement affects skill acquisition. For instance, Campanaro et al. (2020) demonstrated the immediate onset of differential reinforcement was the most efficient arrangement for six of seven comparisons across three participants.

Vladescu and Kodak (2010) reviewed studies evaluating the impact of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition. Their review included four studies, three of which manipulated the schedule of reinforcement in effect for prompted and independent responses. These authors identified several venues for future research (e.g., fading reinforcement for prompted responses across trials) and concluded that, given the scarcity of research on this topic, additional research evaluating the impact of differential reinforcement was necessary to determine the generality of the results attained in previous research. Vladescu and Kodak’s call for additional research likely led to a growing body of research investigating the impact of differential reinforcement on acquisition of novel skills. However, a limitation of their review is the omission of a systematic process to identify relevant research. Moreover, their review is outdated (i.e., 13 years old). Therefore, the purpose of this review was to extend the review completed by Vladescu and Kodak by conducting a systematic search of the literature and synthesizing all studies published between 1980 and 2022 that investigated the impact of differential reinforcement of prompted and independent correct response on skill acquisition. In particular, we sought to determine which iteration of differential reinforcement was most efficacious. We restricted the publication year to 1980 and later because during a preliminary review of the related literature describing the use of differential reinforcement within skill acquisition programs, the earliest article cited was published in 1980 (i.e., Olenick & Pear, 1980). Limitations of the previous research as well as clinical and research recommendations are discussed.

Method

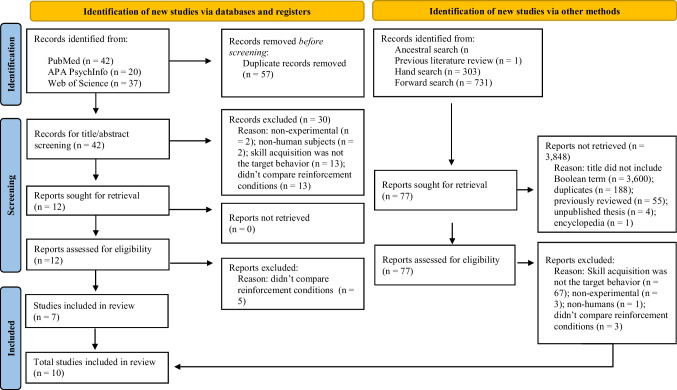

To complete this systematic literature, we employed procedures similar to the PRISMA guidelines for search and inclusion criteria (Page et al., 2021). To identify articles to be included in this review we searched in three databases for articles using numerous Boolean search phrases. We then reviewed the articles identified in the database search to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Furthermore, to ensure our literature review included all relevant articles, we employed three additional search procedures, review of the reference list of articles that met inclusion criteria (i.e., ancestral search), hand search of table of content of a related journal, and a forward search using the “cited by” function of Google Scholar (see PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Modified PRISMA-Literature Search Procedures. Note. Adapted from Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Initial and Extended Search Procedures

In January 2023, we used Web of Science, PubMed, and APA PsyInfo to identify articles evaluating the impact of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition. We restricted the search to articles written in English and published between 1980 and 2022 and used the following Boolean phrases: “differential reinforcement” AND “skill acquisition,” “differential reinforcer” AND “skill acquisition,” “reinforcement magnitude” AND “skill acquisition,” “reinforcement schedule” AND “skill acquisition,” “reinforcement quality” AND “skill acquisition,” “reinforcement immediacy” AND “skill acquisition.” The researchers extracted the results (e.g., title, authors, journal, publication year, abstract) of the database searches into Microsoft Excel and they used the “sort” and the “remove duplicate” functions to organize the results and identify duplicate results.

During the ancestral search, which was completed in February 2023, we reviewed the reference section of all articles which met inclusion criteria upon completion of the full text review (n = 10; see Fig. 1). We selected for further review all articles that included within their title one of the Boolean search terms used during the initial search (i.e., “differential reinforcement”; “differential reinforcer,” “reinforcement magnitude,” “reinforcement schedule,” “reinforcement quality,” or “reinforcement immediacy”) if they had not already been identified during the initial database search. We completed the title and abstract and full text review, if applicable, of the articles identified during the extended search and we repeated this process until no additional articles were identified for review. In addition, we also compared the list of articles we identified for this review to the articles included in the review published by Vladescu and Kodak (2010) to ensure that the articles included in their review were also selected for inclusion in the current review. This process resulted in the identification of three articles for inclusion in this review.

During the hand search procedure, completed in October 2023, we reviewed the table of content of the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis to identify articles published between 1980 and 2022 that included within their title one of the Boolean search terms used during the initial search (e.g., “differential reinforcement”). We restricted our hand search to this journal because nine of the articles that met inclusion criteria were published in this journal. Through the review of the table of contents we identified 3,037 articles. Therefore, we reviewed the titles of 3,037 articles to determine if the title included one of the Boolean search terms (or a plural version of the term) used in the ancestral search. A total of 86 articles included one of the Boolean search terms in the title; 17 of these articles had been identified in the initial database searches. The remaining 69 articles underwent the title and abstract review and 67 were excluded (nonexperimental = 2; the participants were nonhumans = 1; the dependent variable was not a response targeted for increase = 63; did not compare reinforcement conditions = 1) from further review. The remaining two articles underwent the full text review and were excluded from this review because they did not compare at least two reinforcement conditions.

Finally, during the forward search completed in October 2023, we located each of the articles that met inclusion criteria in Google Scholar, clicked on the “cited by” function, and then reviewed the titles of all the articles that cited the articles meeting the inclusion criteria to determine if they included one of the Boolean search term or their plural form (e.g., reinforcement schedules). We identified 731 articles, of which 188 were duplicates. Of these, 16 articles included in their title one of the Boolean search terms used in the initial search; 6 of these had already been selected for inclusion in the current review; 2 had been identified in the initial database searches; 3 consisted of unpublished theses; 1 was a section of an encyclopedia, and 1 was a thesis that has been published and was already selected for inclusion in this review. The remaining three articles underwent the title and abstract review and were excluded (nonexperimental = 1; the dependent variable was not a response targeted for increase = 2).

Title and Abstract Review

During the title and abstract review, articles were excluded if the content of the title or abstract indicated the article was nonexperimental in nature (e.g., a literature review, discussion paper), included nonhuman participants, did not target skill acquisition (e.g., aimed at reducing problem behavior; implemented caregiver training), employed an intervention other than differential reinforcement (e.g., used extinction to decrease problem behavior), or was off-topic (e.g., study on chemotherapy; acupuncture).

Full Text Review

During the full text review, we selected for inclusion articles that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) reported individual participant data; (2) participants were human subjects; (3) the entire article was published in English and in a peer-reviewed journal (e.g., Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis); (4) compared at least two reinforcement conditions; and (5) the article’s primary dependent measure was a response targeted for increase (e.g., tacts, listener responding, discrimination). Articles that compared at least two reinforcement conditions, such as DR 1 vs DR 2 or DR 1 vs no DR, and in at least one of the conditions the reinforcer (e.g., quality/type, amount, schedule, or immediacy of the reinforcer delivered was manipulated) provided for correct prompted and correct independent responses differed met the comparison of reinforcement conditions inclusion criterion. Ten articles met the inclusion criteria and relevant information from each of these articles was extracted during the descriptive synthesis.

Descriptive Synthesis

We summarized the studies included in this review according to the following categories: (1) participant characteristics; (2) setting; (3) reinforcement conditions; (4) within-subject replication; (5) results; and (6) secondary measures. Two researchers independently completed the descriptive synthesis for all studies meeting inclusion criteria. To extract data from the studies, the researchers downloaded a copy of each article and then recorded into a Microsoft Excel file the relevant information. See Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics attained via the descriptive synthesis

| Authors (Publication Year) | Participant Characteristics (# of participants) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (Age), Diagnosis | Communication (# Modality) | Other Skills Repertoires & Prompt Dependency | Target Behavior | Setting | |

| Olenick & Pear (1980) | M (4 yo), M (4 yo), F (4 yo); Down’s Syndrome (2), Microcephaly (1) | Y (1), N (2), (1 Vocal; 2 NA) | Listener: NR (3); VI: Y (3), MI: NR (3), PD: NR (3) | Tact (3) | Small room (3) |

| Touchette & Howard (1984) | M (6 yo), M (7 yo), F (13 yo); MR (2), MR + CP (1) | Y (3) (1 Gestures; 2 NR) | Listener: Y (3); VI: NR (3); MI: NR (3); PD: NR (3) | Audio-visual discrim. (3) | Work area in training center (3) |

| Karsten & Carr (2009) | M (3 yo), M (5 yo); ASD (2) | Y (2) (1 Vocal; 1 Vocal + Gestures) | Listener: NR (2); VI: Y (2); MI: Y (2); PD: NR (2) | Picture sequencing (1), Tact (1) | NR (2) |

| Cividini-Motta & Ahearn (2013) | M (12 yo), M (13 yo), M (16 yo), M (38 yo); ASD (3), ASD + seizure (1) | Y (3), NR (1) (1 VOD; 1 VOD + Signs; 1 Vocal + Signs; 1 NR) | Listener: Y (4); VI: NR (4); MI: NR (4); PD: Y (4) | Visual-visual discrim. (4) | Room adjacent to classroom & classroom (3); room at residence (1) |

| Hausman et al. (2014) | M (16 yo), M (18 yo), M (20 yo); ASD + ID (3) | NR (3) (3 N/A) | Listener: NR (3), VI: NR (3); MI: NR (3), PD: NR (3) | Visual-visual discrim. (2), Spelling (1) | Classroom (2); bedroom (1) |

| Boudreau et al. (2015) | NR (7 yo), NR (8 yo), NR (10 yo); ASD (3) | NR (3) (3 N/A) | Listener: NR (3), VI: Y (3); MI: NR (3), PD: NR (3) | Tact (3) | Learning areas in a school (3) |

| Paden & Kodak (2015) | 4 M (4-5 yo); ASD (4) | Y (4) (4 NR) | Listener: Y (1), NR (3); VI: NR (4); MI: NR (4); PD: NR (4) | Tact (3), audio-visual discrim. (1) | Private therapy room in hospital-based clinic (4) |

| Johnson et al. (2017) | M (8 yo), M (9 yo), M (10 yo); ASD (3) | Y (3) (3 NR) | Listener: Y (3); VI: NR; MI: Y (3); PD: NR (3) | Tact (3), intraverbal (3), audio-visual discrim. (3) | Self-contained classroom in school (3) |

| Campanaro et al. (2020) | M (7.7), F (9.4), M (9.8); ASD (3) | Y (3) (3 NR) | Listener: NR (3); VI: NR (3); MI: NR (3); PD: NR (3) | Tact (3) | Small room in a clinic or home (3) |

| Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla (2021) | F (3 yo), M (4 yo), M (14 yo); ASD (2), Down’s Syndrome (1) | Y (3) (1 PE; 1 Vocal; 1 NR) | Listener: Y (3); VI: Y (1) NR (1); MI: Y (1) NR (1) & Y (1) but topography NR; PD: NR (3) | Motor imitation (1), audio-visual discrim. (1); listener responding (1) | Separate spaces in early intervention classrooms (3) |

NR = Not reported; N/A = Not applicable; M = Male; F = Female; yo = Years old; CP = Cerebral Palsy; Discrim. = Discrimination; VI = Vocal imitation; MI = Motor imitation; PD = Prompt dependency; Listener = Listener responding (e.g., follow directions); Y = Yes; VOD = Voice output device; PE = picture-based communication); MR = Mental retardation

Table 2.

Summary of reinforcement procedures and results attained during the descriptive synthesis

| Authors (Publication Year) | Teaching Procedures (# of participants) | Results (Most Favorable & # of Participants) | Within-Subject Replication (# of participants) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcer Class | Conditions Evaluated | Parameter | Onset of DR | Condition | Parameter/Onset | Replication Attempted | Results Replicated | |

| Olenick & Pear (1980) | Edibles (3) |

No DR (3), DR 1 (3), DR 3 (3) |

Sch. (3) | NR (3) | DR 1 (3) | N/A / N/A | No (3) | N/A (3) |

| Touchette & Howard (1984) | Tokens & Praise (3) |

No DR (3), DR 1 (3), DR 3 (3) |

Sch. (3) | NR (3) |

DR 1 (2), DR 1, No DR, DR 3 equal (1) |

N/A / N/A | No (3) | N/A (3) |

| Karsten & Carr (2009) | Edibles & Praise (2) | No DR (2), DR 1 (2) | Qual. (2) | Imm. (2) | DR 1 (2) | N/A / N/A | Yes (2) |

Partial (1), No (1) |

| Cividini-Motta & Ahearn (2013) | Tokens & Praise (3), Edibles & Praise (1) |

No DR (4), DR 1 (4), DR 2 (4) |

Qual. (4) | Imm. (4) |

DR 1 (3), DR 2 (1) |

N/A / N/A | Partial (4) | Yes (4) |

| Hausman et al. (2014) | Edibles & Praise (3) |

No DR (3), DR 1 Qual (3), DR 1 Sch. (3) |

Sch. (3), Qual. (3) | NR (3) | DR 1 (3) |

Qual. (2), Sch. (1)/ N/A |

Partial (2), No (1) |

Yes (2), N/A (1) |

| Boudreau et al. (2015) | Edibles & Praise (3) | No DR (3), DR 1 Qual. (3), DR 1 Mag. (3) | Qual. (3), Mag. (3) | Imm. (3) |

DR 1 (2), No DR (1) |

Qual. (1), Mag. (1)/ N/A | No (3) | N/A (3) |

| Paden & Kodak (2015) | Edible & Praise (4) |

No DR (4), DR 1 Qual. small mag. (4), DR 1 Qual. larger mag. (4) |

Qual. & Mag. (4) | Delayed (4) | DR 1 large edible (2), DR 1 small edible (2) | No (4) | N/A (4) | |

| Johnson et al. (2017) | Edibles & Praise (3) | No DR (3), DR 1 Qual. (3), DR 1 Mag. (3), DR 1 Sch. (3) | Qual. (3), Mag. (3), Sch. (3) | NR (3) |

DR 1 (2), No DR (1) |

Qual. (2), Qual. & Sch. Equal (1) | Yes (3) | Partial (3) |

| Campanaro et al. (2020) | Edibles & Praise (3) | No DR (3), DR 1 Qual. (3), DR 1 Mag. (3), DR1 Sch. (3) | Qual. (3), Mag. (3), Sch. (3) | Imm., early, delayed (3) | DR 1 (3) | Sch. (2), Qual. & Mag. equal (1) / Imm. (2), Imm. & Early Equal (1) | Partial (3) |

Yes (2), Partial (1) |

| Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla (2021) | Toys & praise (3) | No DR (1), DR 1 Qual. & Onset (3) | Qual. (3) | Imm., early (3) |

N/A (2) No DR (1) |

N/A / Early (1), Imm. (1), Early & Imm. Equal (1) |

Yes (1), No (2) | No (1), N/A (2) |

NR = Not reported; N/A = Not applicable; Qual. = quality; Sch. = schedule; Mag. = Magnitude; Imm. = immediate

Participant Characteristics

We extracted participant characteristics reported in the study including age, sex, diagnoses, skills repertoire including if they had a history of prompt dependency, and target behavior. Regarding their diagnosis, we extracted the information reported in the article verbatim. Regarding the skill repertoire, we extracted data on the participants’ verbal repertoire, listener repertoire, motor or verbal imitation skills, receptive skills, and history of prompt dependency and were coded as “Yes,” “No,” or “NR.” We used “Yes” to indicate the researchers reported the participant had these responses in their repertoire (e.g., if the authors indicated that the participant followed 1- to 2-step directions then a “Yes” was used in regards to listener repertoire) independently of the complexity of their skills; we used “No” when the researchers indicated this response was not part of the participant’s skill repertoire; and we used “NR” when the authors did not report the presence or absence of that response/skill in the participant’s repertoire. In the case of verbal repertoire, we used “Yes” only when the individual engaged in verbal responses other than vocal imitation (i.e., echoic responding) because we extracted information on imitation skills separately. That is, we used “Yes” when the researchers reported that the participant “communicated” or that they could emit tacts, mands, or intraverbals. If the authors reported the participant’s verbal repertoire, we also extracted information about the modality of communication used by each of the participants (i.e., vocal, signs, gestures, picture exchange, speech generating device). In these cases, we used “Not Specified” (NS) when the authors did not specify the modality of communication used by the participant. If the authors reported that the participant did not have a verbal repertoire or did not report the participants verbal repertoire, we coded the participant’s communication modality as “Not Applicable” (N/A). If the article indicated that the participant had a history of prompt dependency, we extracted information on the type of assessment (i.e., interview, record review, direct assessment, functional assessment) employed by the researchers to identify prompt dependency. We also extracted data on the target behavior for each participant. The exact tact (e.g., “intraverbal”; “following direction”) the researchers used to describe the target behavior was recorded. In cases when a discrimination task was taught, we coded the target response as auditory–visual or visual–visual discrimination based on the description provided by the authors regarding the sample (i.e., visual or auditory stimuli) and the comparison stimuli (i.e., visual stimuli).

Setting

Regarding the setting employed to conduct sessions, we extracted the information reported in the article verbatim and included in Table 1 a shortened version (e.g., “self-contained classroom” was recorded for the study which reported using a “self-contained classroom for individuals with developmental disabilities”; Johnson et al., 2017). In cases when the authors did not report the location of sessions, we recorded “NR.”

Reinforcement Conditions

We also reviewed the method section of each manuscript to determine the class of reinforcers employed in the study (i.e., edibles, tangibles, tokens, social consequences, combination), reinforcement conditions evaluated, parameter of reinforcer manipulated (i.e., quality, magnitude, schedule, and/or immediacy), and the specific criteria for onset of differential reinforcement. We coded the type of differential reinforcement conditions employed by the studies as No DR, DR 1, and DR 2, using the same definitions as Cividini-Motta and Ahearn (2013), or as DR 3. Therefore, we defined No DR as providing the same reinforcer for both independent and prompted responses and DR 1 as favoring independent responses (e.g., delivery of most potent reinforcer) while still delivering a reinforcer or appetitive consequence for prompted response (e.g., praise). For studies that evaluated two forms of a DR 1 procedure (e.g., one manipulating quality and another manipulating schedule of reinforcement) we also extracted the parameter manipulated. Finally, we defined the DR 2 condition as also favoring independent responding; however, in this condition no reinforcers were delivered for prompted responses, and the DR 3 condition as favoring prompted responses (e.g., delivery of a reinforcer on a CRF schedule) while delivering a less favored reinforcer for independent response (e.g., delivery of a reinforcer on a FR-3 schedule).

We coded the type of reinforcer parameters as quality, magnitude, schedule, and immediacy. We defined quality of reinforcer as the manipulation of reinforcers relative to the participant’s actual or presumed preference (i.e., praise was a programmed consequence but not included in a preference assessment; in this case it was presumed that praise was less preferred/reinforcing than stimuli identified as highly preferred or reinforcing) towards these reinforcers and/or reinforcing efficacy as determined via preference or reinforcer assessments; magnitude as manipulating the amount of the reinforcer delivered; schedule as manipulating the number of responses required until reinforcement was delivered; immediacy as manipulating the amount of time that elapsed between the emission of a target response and the reinforcer delivery. Finally, we also extracted data on whether the study specified the criteria for implementation of differential reinforcement and whether the authors manipulated the onset of implementation. We defined the onset of differential reinforcement as manipulating the inception of differential reinforcement (i.e., the specific number or percentage of independent responses the participant must emit before differential reinforcement is implemented). Regarding onset of differential reinforcement, we coded as “immediate” when the researchers indicated that differential reinforcement was implemented immediately (e.g., Campanaro et al., 2020) or upon the occurrence of the first instance of an independent and correct response (e.g., Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013), even if participants did not have an opportunity to engage in independent responding during a certain number of sessions (e.g., first sessions included an immediate prompt such as in Boudreau et al., 2015). In addition, although one study included two delayed onset conditions (Campanaro et al., 2020), given the similarity across studies in the criteria for implementing differential reinforcement in the delayed onset condition (i.e., 33%, 40%, 50% independent and correct response), for the purpose of this review we coded as “early onset” the data sets exposed to the 33% and 40% criteria and as “delayed onset” the databased exposed to a 50% and above requirement.

Within-Subject Replication

To determine whether the authors evaluated the impact of each of the independent variable on each of the participants’ responding multiple times (i.e., attempted to replicate results within participants), we reviewed the method section of the article as well as the figures displaying the results. Regarding attempts to replicate results within participants, we coded an article as “Yes” if the authors assessed the impact of all of the conditions with each of the participants at least twice and with different set of stimuli (e.g., evaluated the impact of both No DR and DR 1 with one set of stimuli and then again with another set of stimuli), as “Partial” if the authors assessed the impact of only a subset of the conditions at least twice (e.g., evaluated the impact of DR 1 with multiple set of stimuli but No DR with only one set of stimuli; e.g., Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013), and as “No” if the authors evaluated the effects of each condition only once with each participant. If the authors attempted to replicate the results within participants, we extracted data on whether the same results were attained for each of the participants. That is, we first determined which condition resulted in faster acquisition (e.g., fewer trials to mastery) during the first comparison; then we reviewed the data from subsequent comparisons to determine if the same condition was associated with faster acquisition. We coded these data as “Yes” to indicate successful replication (i.e., the same condition was associated with fewer trials to mastery across all comparisons), as “No” to indicate unsuccessful replication, and as “Partial” to indicate when the same outcome was attained across only a subset of the evaluations (e.g., one out of the three attempts) or if only a portion of the outcomes of the initial evaluation were replicated (e.g., during the first evaluation two conditions were equally efficient; in the second comparison one of these conditions was more efficient than the other). If the authors did not attempt to replicate the results, we coded successful replication as “N/A.”

Results

To determine the most favorable reinforcement condition for each participant we extracted or estimated (i.e., number of sessions multiplied by number of trials per session) the number of trials to meet mastery criteria. If multiple data sets were available for a participant, we calculated the arithmetic mean number of trials to reach mastery criteria per condition across the datasets. We then coded the reinforcement condition as the most favorable (i.e., condition with the most data sets reaching mastery; least number of trials or average number of trials to mastery in cases when two or more conditions were associated with the same number of datasets meeting mastery criteria). We coded the reinforcement conditions as equally favorable when participants required the same number or arithmetic mean number of trials to reach mastery or if the number of trials did not differ by more than 10 trials (e.g., one condition required 60 trials, another required 68). If the mastery criteria were not met under a specific condition, we coded that condition as “N/A.” For two of the articles (Hausman et al., 2014; Paden & Kodak, 2015), the mastery criteria were not specified; however, Paden and Kodak (2015) indicated that their participants met the mastery criteria. For these articles we presumed that sessions ceased once mastery was met if the authors did not modify the condition in effect due to lack of progress (e.g., performance remained low at the end of the phase and the reinforcement condition in effect was replaced or modified). Thus, for these articles we estimated the number of trials to mastery by multiplying the total number of sessions completed by the number of trials per session. For one of the articles, Karsten and Carr (2009) specified the mastery criteria but our visual inspection of the data indicated that in some cases the mastery criteria were not met prior to a phase change (e.g., the first phase for Steve ended before mastery criteria were met in the differential reinforcement condition); in these cases, we coded the data set for that condition as “N/A.” In addition, for one participant, Sarah, from Cariveau and La Cruz Montilla (2021), the description the authors provided of some of the results differed from the data shown on the figure; therefore, we used the data shown in the figure to determine efficacy of the reinforcement procedures. For the study completed by Olenick and Pear (1980) we could not calculate trials to mastery because the authors reported the number of targets (tacts) each participant mastered during each reinforcement condition (termed “phase” by the authors). Thus, for this study we deemed the condition associated with mastery of more tacts as the most favorable condition. Finally, for studies which compared multiple differential reinforcement conditions that differed regarding the parameter manipulated (e.g., DR 1 quality; DR 1 schedule) we identified the most favorable parameter by determining the one which required fewer trials to mastery, even in cases where No DR was the most favorite condition overall. If multiple comparisons were completed, we coded as the most favorable parameter the one that resulted in mastery of more stimulus sets; if two or more parameters were associated with the mastery of the same number of stimulus sets, then we used the average number of trials to mastery to determine the most favorable (i.e., fewest trials to mastery).

Secondary Measures

We sought to extract data on the types of social validity (i.e., questionnaire, interview, rating scale, preference assessment) and generalization assessments (i.e., across stimuli, people, environment) employed by the studies. In addition, we planned to record the respondent (i.e., participant, caregiver, clinical team) of the social validity assessment and whether results of the social validity and generalization assessments were positive (e.g., respondent indicated enjoying the procedures employed; seeing value in this type of study; skills generalized to a novel therapist). However, no studies included social validity assessments. Only two studies included a generalization assessment. Touchette and Howard (1984), assessed generalization across tasks and generalization occurred for all participants. Johnson et al. (2017) assessed generalization across tasks and generalization did not occur for any participants. Due to the lack of these measures, no additional information on these characteristics of the studies will be included in the results section.

Interrater Agreement (IRA)

We calculated interrater agreement (IRA) for the various steps of the search procedure and for the descriptive synthesis. For the initial database search a second person (i.e., rater) completed the search procedures for two out of the three databases and IRA (i.e., the exact same articles were identified by the two raters) was 100%. A second person independently completed the title and abstract review and the full text review. We calculated IRA by determining whether the two raters assigned the same code (“1” was used for articles selected for further review; “0” was used for articles that meet the exclusion) to each of the articles. For the title and abstract review, we calculated IRA for 42 out of 42 articles (100%) and the initial IRA score as 95.24%. Two raters met and discussed the two articles with disagreement until they agreed on whether to include the articles in the full text review, resulting in an IRA of 100%. For the full text review, we calculated IRA for 12 out of 12 articles (100%) and the initial IRA score was 91.67%. The article with disagreement between the two raters (Fiske et al., 2014) was reviewed by two additional doctorate level behavior analysts (i.e., second author; a faculty with expertise on skill acquisition) and both reviewers concluded that, based on the description of the procedures, that the programmed consequences for responding did not meet the differential reinforcement criteria chosen for this review but likely that the procedures employed with one out of the three participants met our criteria of differential reinforcement. Therefore, the article was excluded, resulting in a final IRA score of 100%. We calculated IRA for the descriptive synthesis for 100% of the articles (10 of the 10 articles) by comparing the data recorded (i.e., code assigned, or information entered for each item of the items coded during the descriptive synthesis) by each of the raters. We tallied the number of items with agreement, divided by the total number of items coded for each article, and multiplied by 100. The initial arithmetic mean IRA score was 97.44% (range: 94.40%–100%). The two raters discussed disagreements until they agreed on the accurate code; thus, the final IRA was 100%.

Procedures Employed to Minimize Bias

To minimize bias in the identification and synthesis of relevant literature, we employed many of the procedures outlined in the ROBIS (Whiting et al., 2016), a tool developed to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews. These include a predetermined research question, objective inclusion and exclusion criteria, searching for literature in multiple databases, employing multiple additional strategies to identify relevant studies, and objective description of the data to be extracted during the descriptive synthesis. Moreover, two independent raters, which include two doctoral faculty and a doctoral student, independently completed all steps of the initial database search, title and abstract review, full text review, and descriptive synthesis. However, given our inclusion criteria consisted of research published in English, in peer review journals, and between 1980 and 2022, this review was likely affected by publication bias (i.e., file drawer problem). Moreover, this review potentially omitted relevant literature published in a language other than English and prior to 1980.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Sex, Age, and Diagnoses

There was a total of 31 participants across the 10 studies reviewed. All but one study (Boudreau et al., 2015) reported the sex of their participants. Twenty-four participants were male (77.4%), four were female (12.9%), and for three participant their sex was not reported (9.7%). All but one study (Paden & Kodak, 2015) reported the specific age of each participant and for these the arithmetic mean age of participants was 10.3 years (range: 3- to 38-years-old). For Paden and Kodak (2015), participants’ ages ranged from 4 to 5 years. All studies in the review reported participant diagnoses. Twenty-four participants were diagnosed with ASD (77.4%) and of those participants, 12.5% also had an ID (n = 3) and 4.2% had a seizure disorder (n = 1). The remaining participants were diagnosed with mental retardation (n = 2), mental retardation and cerebral palsy (n = 1), Down’s Syndrome (n = 3) or microcephaly (n = 1).

Skills Repertoires and Prompt Dependency

Across the studies, the authors reported information about participants’ verbal repertoires for 24 of the participants. Of these participants, the authors indicated that 91.7% (n = 22) had a verbal repertoire and 8.3% (n = 2) did not have a verbal repertoire. The authors specified the modality of communication used by the participant for 40.9% (n = 9) of the 22 participants with a verbal repertoire; five participants communicated using vocalizations alone or in combination with gestures, one used a picture-based communication, two used a voice-output device alone or in combination with manual signs, and one employed gesture alone. For 59.1% (n = 13) of the participants with a verbal repertoire, the authors did not specify the communication modality but for many of them the authors’ description suggested the participant communicated using vocalizations.

Some of the articles included in this review provided additional information about the participants’ skills repertoire (i.e., listener and imitation skills) and behavior excesses (i.e., prompt dependency). The authors reported the presence or absence of listener skills for 45.2% of participants (n = 14) and all of them were reported as having at least some listener responding (e.g., follow simple instructions). The authors reported the presence of vocal and/or motor imitation skills for 45.2% of participants (n = 14). Of those participants, the authors indicated that 50.0% (n = 7), 28.6% (n = 4), and 14.3% (n = 2) engaged in vocal imitation, motor imitation, or both, respectively; for one participant the authors indicated they could imitate but the topography (motor or vocal) was not specified (Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021). Additionally, for 54.8% of the participants the authors did not specify whether the participants had an imitative repertoire (i.e., vocal or motor imitation skills; n = 17) and for one participant the authors indicated they could imitate but the topography (motor or vocal) was not specified (Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021). Although the authors did not report the presence or absence of prompt dependency for most participants (n = 27), for Cividini-Motta and Ahearn (2013), this was a participant inclusion criterion. In this study the prompt dependency assessment consisted of a combination of clinical team nomination, two observations of a matching-to-sample program, and a record review. Moreover, the authors selected for inclusion participants that waited for the teacher’s prompt on at least 80% of the trials completed during the observations and for which the record review showed that they quickly moved through prompt hierarchies but rarely emitted correct responses independently.

Across the studies included in this review, the authors taught various responses to their participants and for some participants, the authors taught more than one target behavior (e.g., a tact and an intraverbal). The authors taught tacts to 51.6% (n = 16) and discrimination skills (i.e., auditory–visual, visual–visual) to 45.2% (n = 14) of the participants. In addition, the authors targeted picture sequencing to one participant (Karsten & Carr, 2009), following directions to one participant (Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021), motor imitation to one participant (Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021), intraverbals to three participants (Johnson et al., 2017), and spelling to one participant (Hausman et al., 2014).

Settings

The authors did not report the location of sessions for two of the participants (Karsten & Carr, 2009). For the remaining participants, the authors conducted sessions in a classroom (n = 2), a room adjacent to the classroom and in the classroom (n = 3), bedroom (n = 1), self-contained classroom in a school (n = 3), room at the residence (n = 1), private therapy room in a hospital-based clinic (n = 4), separate space in an early intervention classroom (n = 3), small room at the clinic or at the participant’s home (n = 3), small room (n = 3), in the participant’s learning areas in the school (n = 3), or regularly used work area in training center (n = 3).

Reinforcement Conditions

Reinforcer Class and Differential Reinforcement Conditions

Across studies, the class of reinforcers used as the consequence for target responses varied. The authors used edibles or edibles plus praise with 71.0% (n = 22), tokens plus praise with 19.3% (n = 6), and toys or toys plus praise with 9.7% (n = 3) of the participants. Regarding the differential reinforcement conditions, 100% of the participants experienced a DR 1 condition (n = 31), 90.3% a No DR condition (n = 28), 12.9% a DR 2 condition (n = 4), and 19.4% a DR 3 condition (n = 6).

Parameters Manipulated

Quality of Reinforcers

For 80.6% of the participants (n = 25), the authors manipulated the quality of reinforcer (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021; Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2017; Karsten & Carr, 2009; Paden & Kodak, 2015). That is, the quality of the reinforcer provided for independent and for prompted correct responses differed. Regarding the class of reinforcers, across these 25 participants, the authors used edibles plus praise with 76.0% of participants (n = 19), tokens plus praise with 12.0% of participants (n = 3), and toy plus praise with 12.0% of the participants (n = 3). In addition, 92.0% of the 25 participants (n = 23) experienced the No DR condition, in which the quality of the reinforcer is equal for prompted and independent responses, 100% of these participants experienced the DR 1 condition, in which the reinforcer is of higher quality for the independent response compared to the reinforcer for the prompted response, and 16.0% (n = 4) experienced the DR 2 condition, in which the independent response is reinforced with a high-quality reinforcer (e.g., tokens plus praise) and the prompted response is put on extinction (no consequence). None of the participants experienced the DR 3 condition within this parameter.

Magnitude of Reinforcers

The authors manipulated the magnitude of the reinforcer with 41.9% (n = 13) of the participants (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2017; Paden & Kodak, 2015). That is, the magnitude of the reinforcer provided for independent and for prompted correct responses differed. Regarding the class of reinforcer, the authors used edibles plus praise with all 13 participants. Of these 13 participants, 100% experienced the No DR and DR 1 conditions. In the DR 1 arrangement, the large magnitude reinforcer (e.g., 20 s of social reinforcement) was delivered contingent on an independent response and a smaller magnitude of reinforcement was delivered contingent on a prompted response (e.g., 5 s of social reinforcement). None of the participants experienced the DR 2 and DR 3 conditions.

Schedule of Reinforcement

The authors manipulated the schedule of reinforcement with 48.4% (n = 15) of the participants (Campanaro et al., 2020; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2017; Olenick & Pear, 1980; Touchette & Howard, 1984). In particular, the schedule of reinforcement in effect for independent correct relative to prompted responses differed. Regarding the class of reinforcers, the authors used edibles plus praise for (n = 9), edibles alone (n = 3), and tokens plus praise (n = 3). 100% of the participants (n = 15) experienced the DR 1 condition (e.g., CRF schedule for independent responses; FR3 for prompted responses) and the No DR condition (e.g., CRF schedule for both independent and prompted responses). In addition, 40.0% of the participants (n = 6) experienced the DR 3 condition (e.g., CRF for prompted responses; FR 3 for independent responses) and none experienced the DR 2 condition (e.g., CRF for independent responses; extinction for prompted responses). Three participants experienced an additional variation of the No DR condition in which the independent and prompted responses were tracked on different schedules, but were reinforced using equal FR schedules (e.g., reinforcement delivery was contingent on the participant emitting six correct prompted responses and the authors did not restart the schedule following incorrect responses; Olenick & Pear, 1980).

Relative Parameter Evaluations

The authors evaluated the impact of multiple DR 1 conditions, which differed regarding the reinforcement parameter manipulated (e.g., quality vs. schedule) with 38.7% of the participants (n = 12; Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2017). For instance, in the study by Johnson et al. (2017), in one DR 1 condition the authors delivered edible plus praise for independent responses and praise alone for prompted responses (i.e., DR 1 Quality); in another DR 1 condition the authors provided edible plus praise for independent responses and a small edible plus praise for prompted responses (i.e., DR 1 Magnitude); in the third DR 1 condition the authors delivered edible plus praise following each independent response and edible plus praise on a FR 3 schedule for prompted responses. Across the studies comparing iterations of the DR 1 condition, six participants experienced two variations (DR 1 schedule vs. DR1 quality; DR 1 quality vs. DR 1 magnitude) and another six experienced all three DR 1 conditions (i.e., DR 1 quality, DR 1 schedule, DR 1 magnitude). It is important to note that the study by Paden and Kodak (2015) also evaluated two DR 1 conditions, both of which involved manipulating the quality of the reinforcer provided following independent and prompted responses to favor independent responses; however, the two conditions differed regarding the magnitude of the edible provided following independent responses (i.e., small vs. large). That is, this study did not compare two differing DR 1 conditions, one in which quality and another in which magnitude were manipulated. Instead, the quality manipulation remained constant across both conditions.

Onset of Differential Reinforcement

The authors specified the criteria for onset of implementation of differential reinforcement for 61.3% of participants (n = 19); nine of these experienced immediate onset (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021; Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013; Karsten & Carr, 2009); four experienced delayed (Paden & Kodak, 2015); three experienced immediate, early, and delayed onset (Campanaro et al., 2020); and three experienced immediate and early onset (Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021). In the Campanaro et al. (2020) study each participant experienced quality, magnitude, and schedule manipulations first. During the subsequent onset of differential reinforcement phase, which included immediate (i.e., reinforcement favors independent responses at the onset of training), early (i.e., reinforcement favors independent responses when at least 33% of the responses emitted are independent) and delayed (reinforcement favors independent responses when at least 50% of the responses emitted are independent) conditions, the authors employed the parameter associated with faster acquisition. Likewise, Cariveau and La Cruz Montilla (2021) manipulated the quality of reinforcement and their participants experienced two onset conditions, immediate and delayed onset of differential reinforcement. During the immediate onset, the authors delivered the high-quality reinforcer (i.e., praise and 20 s of the preferred tangible item) following unprompted correct responses and the low-quality reinforcer (i.e., brief praise statement) contingent on prompted correct responses. On the other hand, during the delayed onset, the authors provided praise and 20 s access to a preferred item for unprompted and correct responses until correct responding increased to at least 40% across two consecutive sessions. The authors subsequently provided the high-quality reinforcer contingent on independent correct responses and the low-quality reinforcer following prompted correct responses.

Results and Within-Subject Replication

This literature review identified 10 articles that evaluated the effects of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition. As noted above, studies differed regarding participants, target responses, and the type of differential reinforcement evaluated. Results of these studies indicated that the DR 1, DR 2, and No DR conditions were the most favorable for 24, one, and three participants, respectively. For one participant the DR 1, DR 3, and No DR conditions were equally favorable. Moreover, for two participants (Jerome and Stan; Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021) only the DR 1 condition was evaluated because the study compared differing onsets of differential reinforcement. The DR 3 condition was never associated with better outcomes.

The authors manipulated the quality of the reinforcer in eight studies that compared the DR 1 condition to another reinforcement condition (e.g., No DR, DR 2) or a variation of the DR 1 condition (i.e., DR 1 Schedule) and with a total of 23 participants (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; one participant from Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021; Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al, 2017; Karsten & Carr, 2009; Paden & Kodak, 2015). Across these studies, the DR 1 condition was the most favorable for 82.6% of the participants (n = 19), the No DR for 13.0% (n = 3), and the DR 2 for 4.3% (n = 1). The DR 3 condition was not included in any of these evaluations. Of the studies (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2017) that evaluated the relative effectiveness of DR 1 Quality in comparison to DR 1 involving the manipulation of other reinforcement parameters (n = 12), the DR 1 condition involving manipulating the quality (DR 1 Quality) of the reinforcer was most favorable for five participants and equally favorable as another parameter for two participants; DR 1 Schedule was most favorable for three participants and DR 1 Magnitude for one participants. For one participant, the No DR condition was most favorable.

The authors manipulated the magnitude of the reinforcer in three studies (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2017) and with nine participants. Across these studies the DR 1 condition was the most favorable for 77.8% (n = 7) of the participants and the No DR condition with 22.2% (n = 2). All three studies also included a comparison of DR 1 Magnitude to DR 1 Schedule and/or DR 1 Quality and their results indicated that DR 1 Magnitude was most favorable for one participant and equally favorable as DR 1 Quality for one participant. DR 1 Quality was most favorable for three participants, DR 1 Schedule was better for two participants, and DR 1 Quality and Schedule were equally favorable for one participant. For one participant, the No DR condition was most favorable.

The authors manipulated the schedule of reinforcement with 15 participants across five studies (Campanaro et al., 2020; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al, 2017; Olenick & Pear, 1980; Touchette & Howard, 1984) and of these, the DR 1 condition was most favorable for 86.7% (n = 13) of the participants, the No DR condition for 6.7% (n = 1), and the DR 1, No DR, and DR 3 conditions were equal for 6.7% (n = 1). For the nine participants (Campanaro et al., 2020; Hausman et al., 2014; Johnson et al, 2017) who experienced the DR 1 Schedule and other iterations of the DR 1 condition, DR 1 with schedule manipulation was most favorable for three participants and with quality manipulation for four participants. The DR 1 Magnitude was never most favorable but was equally as favorable as DR 1 Quality for one participant. Likewise, DR 1 Schedule and DR 1 Quality were equally favorable for one participant.

The authors manipulated the onset of differential reinforcement with six participants (Campanaro et al., 2020; Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021) and all these participants experienced the DR 1 condition with differing criteria for onset (i.e., immediate, early, delayed). The results from the manipulation of the onset of a differential reinforcement procedure indicated the DR 1 with immediate onset was the most favorable for 50.0% of the participants (n = 3) and resulted in similar outcomes as early onset for 33.3% of the participants (n = 2).

Across the studies included in this review, the authors attempted a within-subject replication with six of the participants (19.4%) and results of the initial evaluation were partially replicated with four participants (66.7%). In addition, the authors attempted a partial replication with nine participants and the results were replicated or partially replicated with these nine (100%) participants. The authors did not attempt to replicate outcomes with the remaining 16 participants (51.6%).

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized literature evaluating the impact of differential reinforcement on skill acquisition. A total of 10 articles were included and we summarized these studies regarding participants’ characteristics, target behaviors, acquisition evaluation, and results. Across these studies, the DR 1 condition, which entailed the delivery of a more potent reinforcer for independent responses and a less potent reinforcer for prompted responses (Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013), was the most favorable for 24 out of 31 participants. Moreover, results of the current literature review indicated that when the onset of differential reinforcement was manipulated (Campanaro et al., 2020; Cariveau & La Cruz Montilla, 2021), immediate onset and early onset were similarly favorable.

Both Vladescu and Kodak (2010) and our review found arranging differential reinforcement to favor independent correct responses over prompted responses will lead to more rapid skill acquisition; however, there are some differences across these two reviews worth noting. First, Vladescu and Kodak noted that only one study in their review (Karsten & Carr, 2009) removed high quality reinforcement for prompted responses after the first correct independent response (i.e., immediate onset of differential reinforcement). The authors stated that some individuals may require more exposure to reinforcement of prompted responses prior to the onset of differential reinforcement (i.e., delaying the onset of differential reinforcement) that is subsequently faded. Results of the current review indicated that immediate onset was more or as favorable as early onset of differential reinforcement, suggesting delaying the onset of differential reinforcement may not be necessary.

Second, Vladescu and Kodak (2010) only identified and described articles that manipulated two of the parameters of reinforcement, quality, and schedules of reinforcement, whereas the current review also identified studies that manipulated the magnitude of reinforcement. Along the same lines, Vladescu and Kodak did not include specific recommendations for selecting different differential reinforcement conditions (DR 1, DR 2, and DR 3), likely due to the limited number of articles identified for that review. On the other hand, our review included a larger number of articles, and the DR 1 condition was deemed the most favorable reinforcement condition for most of the participants. Therefore, based on these outcomes, we could tentatively recommend the DR 1 condition for clinicians considering employing differential reinforcement with their clients.

The current review offers multiple venues for future research related to both gaps in the literature as well as limitations identified in the reviewed articles. The major gaps identified in this review include lack of social validity, generalization, maintenance measures, evaluation of DR within the immediacy parameter, and inclusion of individuals’ whose responding were prompt dependent. The inclusion of a social validity measure can facilitate treatment selection and is important in determining the feasibility of implementation of the procedure, as well as client and caregiver preference for or acceptability of the procedure. As described previously, generalization across behavior was only assessed in Touchette and Howard (1984) and Johnson et al. (2017) and generalization across settings or people were not evaluated in any of the articles included in this review. In addition, given that all studies reviewed used differential reinforcement within a discrete trial teaching format, future research should evaluate differential reinforcement across multiple teaching formats (i.e., discrete trial teaching, incidental teaching, naturalistic teaching, and/or task analyses) with each participant to see if the same results are attained. Along the same lines, previous research on differential reinforcement has not evaluated the feasibility of the implementation of a differential reinforcement procedure in a clinical setting and it is unclear whether more treatment integrity errors occur when conducting DR 1, DR 2, or DR 3 conditions and whether these errors would affect outcomes. Finally, maintenance data could be helpful to collect to determine if the effects of differential reinforcements on skill acquisition persisted over time.

Furthermore, no study in this review manipulated the immediacy parameter of reinforcement or compared immediacy to other parameters. However, as discussed by previous research (e.g., Karsten & Carr, 2009), the delivery of reinforcement is often delayed following a prompted correct response in comparison to an independent correct response. Finally, Cividini-Motta and Ahearn (2013) is the only study included in the review to assess the impact of differential reinforcement on acquisition of skills by individuals whose responding was prompt dependent. Another study by Gorgan and Kodak (2019) also evaluated the impact of DR on prompt dependent responding, however, that study compared the impact of DR, DR with prompt fading, and extended response interval (i.e., the learner was given up to 10 s to emit a response; no prompts were provided) on responding, and therefore did not meet our inclusion criteria. It is also important to note that in the study completed by Gorgan and Kodak the most effective and efficient procedure differed across participants and the DR condition was most effective and efficient for only one participant. Due to lack of literature regarding prompt dependency, future research should continue to explore the variables responsible for prompt-dependent responding. For instance, Campanaro et al. (2020) explained that if differential reinforcement is not implemented (i.e., No DR condition), the reinforcement of the prompted responses may lead to responding that is persistently dependent on the presentation of prompts.

In addition to identifying gaps in the literature, our literature review identified several limitations of the current literature on differential reinforcement. First, omission of a control condition (e.g., Touchette & Howard, 1984) or a baseline phase (e.g., Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013; Karsten & Carr, 2009; Olenick & Pear, 1980; Touchette & Howard, 1984) are seen frequently across studies. Second, two of the studies reviewed did not include mastery criteria (Hausman et al., 2014; Paden & Kodak, 2015). Because of this, it is unclear how termination of the procedures was determined. In addition, only two studies assessed the DR 3 condition (Olenick & Pear, 1980; Touchette & Howard, 1984), and both manipulated that schedule of reinforcement. Given this, responding in a DR 3 condition when other parameters are manipulated remains unknown. However, given because DR 3 involves reinforcement favoring prompted responses over independent responses, it is conceivable that DR 3 would be less favorable than no DR, DR 1, or DR 2.

Third, many of the previously published studies lacked demographic information on participants, as well as a detailed description of the participants’ skills repertoire, which make assessing generality of the outcomes to other individuals difficult. In addition, various components of the instructional procedures, which differed across studies, may affect acquisition. Regarding emission of prompted responding, it is suggested that the lower response effort associated with emission of a prompted response may be, at least partially, responsible for the persistence of these responses (Karsten & Carr, 2009). Likewise, independent responding may be maintained by negative reinforcement. For instance, in a least-to-most prompting procedure, independent correct responses avoid the presentation of intrusive-prompts (Karsten & Carr, 2009; Paden & Kodak, 2015) and in studies that include an error correction, independent correct responses may be negatively reinforced by the avoidance of the error correction (Karsten & Carr, 2009).

Fourth, a differential reinforcement procedure was technically in effect in the No DR condition for some studies due to the delay in reinforcement delivery. The delay to reinforcement delivery when independent correct responses are emitted is likely relatively shorter than the delay to reinforcement during trials with prompted correct responses (Hausman et al., 2014). In addition, in studies in which an errorless teaching procedure was not employed, prompts were sometimes provided following an error and thus many instances of prompted responses were preceded by an error. In these cases, although no DR was programmed, the delay to reinforcer delivery during trials in which an error was emitted prior to the prompted response, was longer than in trials in which the response was correct (e.g., Karsten & Carr, 2009).

Finally, outcomes of some of the previous studies may also have been affected by condition sequences, carry over across conditions, response effort associated with the target response, and participants’ reinforcement history (e.g., experience with different reinforcement conditions; instructional control). For instance, for studies in which participants were exposed to the No DR condition initially (e.g., Touchette & Howard, 1984), results may have been affected by a sequence effect. That is, frequent engagement in the prompted responses when differential reinforcement was in effect may have been due to previous contact with the high-value reinforcement during the No DR condition (Boudreau et al., 2015; Touchette & Howard, 1984). Outcomes of studies that employed an adapted alternating treatments design may have been affected by carry over effects or multiple treatment interference (e.g., Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Cividini-Motta & Ahearn, 2013). This also may be due to failed discrimination of conditions by the participants (Boudreau et al., 2015). Of the studies that attempted to replicate outcomes within participants, lack of replication indicates that a variable other than the programmed independent variable may have been responsible for the outcomes (e.g., differing effort associated with each of the target responses assigned to each of the condition; Cariveau et al., 2022). Moreover, differing results across participants may have been the product of each participant’s history with differential reinforcement. For instance, Kay et al. (2020) found that previous exposure to specific prompt types might affect outcomes of a prompt comparison evaluation. Lastly, the participants in Paden and Kodak (2015) had a history of reinforcement in similar discrete trial teaching settings; thus, their responding may have been under the instructional control of the characteristics of the environment.

Results of this literature review have immediate implication to practice. Findings from multiple studies indicate the most efficient differential reinforcement condition and parameter manipulation is likely specific to each participant (Boudreau et al., 2015; Campanaro et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2017). Therefore, it may be necessary for clinicians to compare various differential reinforcement procedures to identify the most efficient procedure for their client and to complete a parameter sensitive assessment, like the ones conducted by MacNaul and Cividini-Motta (2021), to determine which parameter of reinforcement to include in the differential reinforcement procedures. However, the value of these assessments, relative to the time required to conduct, is unclear and should be considered (Johnson et al., 2017).

Clinicians considering the use of differential reinforcement within skill acquisition programs must also consider the onset of differential reinforcement. Results of earlier studies suggest that differential reinforcement should not be implemented immediately (Boudreau et al., 2015; Hausman et al., 2014); however, in the study completed by Campanaro et al. (2020) for two of three participants, immediate onset was most efficient in promoting skill acquisition. Moreover, in reviewing studies that manipulated the onset of differential reinforcement, it is important to note the criterion of immediate onset of differential reinforcement differed across participant or studies. In particular, differential reinforcement could not be implemented until the occurrence of the first independent response (e.g., Karsten & Carr, 2009), which differed across participants and, in some studies, participants did not have an opportunity to respond independently during the first few sessions because prompts were provided immediately during a specified number of sessions (e.g., Boudreau et al., 2015). Clinicians should consider the findings from these studies to adequately decide at what point in skill acquisition to implement differential reinforcement.

There are some limitations to the current literature review. First, this review included only literature published in peer-reviewed outlets. The inclusion of only published research was intended to ensure peer review of all included studies to decrease bias. Nevertheless, the exclusion of gray research (unpublished research) is also subject to bias (Tincani & Travers, 2019) because we are not able to detect any differences between the findings of published and unpublished studies. Second, the categories included in our descriptive synthesis are not all encompassing, and it is possible there are other categories that would allow for detection of important variables (e.g., number of sessions in baseline).

In summary, this review examined 10 studies in which differential reinforcement was implemented for skill acquisition. The overall findings of these studies suggest that the most efficient differential reinforcement variation is the one that delivers a more potent reinforcer following independent responding whereas a less potent reinforcer is provided following prompted responding (i.e., DR 1). Moreover, the DR 1 condition did not appear to hinder skill acquisition and differential reinforcement was shown to be most efficient when the reinforcer arrangement manipulates the quality of the reinforcer (i.e., higher-preference reinforcer for independent responses, lower-preference reinforcer for prompted responses). Based on these results, clinicians considering embedding differential reinforcement into skill acquisition programming should consider using a DR 1 condition. Moreover, given that sensitivity to reinforcer parameters vary across individuals, to identify the most appropriate iteration of differential reinforcement for specific learner, clinicians are encouraged to conduct an assessment-based instruction (Kodak & Halbur, 2021) comparing different iterations of differential reinforcement. Nevertheless, Vladescu and Kodak (2010) and this review highlight the limited number of studies published on differential reinforcement and skill acquisition. Therefore, more research in this area is needed to better inform clinical practices.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this research.

Data availability

The data generated during the study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not obtained because this article consists of a literature review. No participants were recruited for this article.

Informed consent

Parental consent/participant assent were not obtained because this article did not include participant.

Footnotes

Portions of this article served as the third author’s thesis, which was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in applied behavior analysis at the University of South Florida.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

*Denotes Articles Included in the Review

- Alzrayer NM, Aldabas R, Alhossein A, Alharthi H. Naturalistic teaching approach to develop spontaneous vocalizations and augmented communication in children with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative & Alternative Communication. 2021;37(1):14–24. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2021.1881825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Boudreau, B. A., Vladescu, J. C., Kodak, T. M., Argott, P. J., & Kisamore, A. N. (2015). A comparison of differential reinforcement procedures with children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 48(4), 918–923. 10.1002/jaba.232 [DOI] [PubMed]

- *Campanaro, A. M., Vladescu, J. C., Kodak, T., DeBar, R. M., & Nippes, K. C. (2020). Comparing skill acquisition under varying onsets of differential reinforcement: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(2), 690–706. 10.1002/jaba.615 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cariveau T, Helvey CI, Moseley TK, Hester J. Equating and assigning targets in the adapted alternating treatments design: Review of special education journals. Remedial & Special Education. 2022;43(1):58–71. doi: 10.1177/0741932521996071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Cariveau, T., & La Cruz Montilla, A. (2021). Effects of the onset of differential reinforcer quality on skill acquisition. Behavior Modification, 46(4), 732–754. 10.1177/0145445520988142 [DOI] [PubMed]

- *Cividini-Motta, C., & Ahearn, W. H. (2013). Effects of two variations of differential reinforcement on prompt dependency. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 46(3), 640–650. 10.1002/jaba.67 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Delprato DJ. Comparison of discrete-trial and normalized behavioral language intervention for young children with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(3):315–325. doi: 10.1023/a:1010747303957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske KE, Cohen AP, Bamond MJ, Delmolino L, LaRue RH, Sloman KN. The effects of magnitude-based differential reinforcement on the skill acquisition of children with autism. Journal of Behavior Education. 2014;23(4):470–487. doi: 10.1007/s10864-014-9211-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores M, Ganz J. Effects of direct instruction on the reading comprehension of students with autism and developmental disabilities. Education & Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;44(1):39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgan EM, Kodak T. Comparison of interventions to treat prompt dependence for children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(4):1049–1063. doi: 10.1002/jaba.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hausman, N. L., Ingvarsson, E. T., & Kahng, S. (2014). A comparison of reinforcement schedules to increase independent responding in individuals with intellectual disabilities.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(1), 155–159. 10.1002/jaba.85 [DOI] [PubMed]

- *Johnson, K. A., Vladescu, J. C., Kodak, T., Sidener, T. M. (2017).An assessment of differential reinforcement procedures for learners with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(2), 290–303. 10.1002/jaba.372 [DOI] [PubMed]

- *Karsten, A. M., & Carr, J. E. (2009).The effects of differential reinforcement of unprompted responding on the skill acquisition of children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(2), 327–334. 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kay JC, Kisamore AN, Vladescu JC, Sidener TM, Reeve KF, Taylor-Santa C, Pantano NA. Effects of exposure to prompts on the acquisition of intraverbals in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):493–507. doi: 10.1002/jaba.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ME, Lerman DC, Van Camp CM. The effects of competing reinforcement schedules on the acquisition of functional communication. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(1):59–63. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Halbur M. A tutorial for the design and use of assessment-based instruction in practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2021;14(1):166–180. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00497-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman DC, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Discrete trial training. In: Lang R, Hancock TB, Singh NN, editors. Early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Springer; 2016. pp. 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- MacNaul HL, Cividini-Motta C. Differential reinforcement without extinction: An assessment of sensitivity to and effects of reinforcer parameter manipulations [Manuscript submitted for publication] University of South Florida; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MacNaul HL, Neely LC. Systematic review of differential reinforcement of alternative behavior without extinction for individuals with autism. Behavior Modification. 2018;42(3):398–421. doi: 10.1177/0145445517740321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Olenick, D. L., & Pear, J. J. (1980). Differential reinforcement of correct responses to probes and prompts in picture‐name training with severely retarded children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13(1), 77–89. 10.1901/jaba.1980.13-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]