Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review is to summarize current clinical knowledge on the prevalence and types of meniscus pathology seen with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, as well as surgical techniques, clinical outcomes, and rehabilitation following operative management of these pathologies.

Recent Findings

Meniscus pathology with concomitant ACL injury is relatively common, with reports of meniscus pathology identified in 21–64% of operative ACL injuries. These concomitant injuries have been associated with increased age and body mass index. Lateral meniscus pathology is more common in acute ACL injury, while medial meniscus pathology is more typical in chronic ACL deficiency. Meniscus tear patterns associated with concomitant ACL injury include meniscus root tears, lateral meniscus oblique radial tears of the posterior horn (14%), and ramp lesions of the medial meniscus (8–24%). These meniscal pathologies with concomitant ACL injury are associated with increased rotational laxity and meniscal extrusion. There is a paucity of comparative studies to determine the optimal meniscus repair technique, as well as rehabilitation protocol, depending on specific tear pattern, location, and ACL reconstruction technique.

Summary

There has been a substantial increase in recent publications demonstrating the importance of meniscus repair at the time of ACL repair or reconstruction to restore knee biomechanics and reduce the risk of progressive osteoarthritic degeneration. Through these studies, there has been a growing understanding of the meniscus tear patterns commonly identified or nearly missed during ACL reconstruction. Surgical management of meniscal pathology with concomitant ACL injury implements the same principles as utilized in the setting of isolated meniscus repair alone: anatomic reduction, biologic preparation and augmentation, and circumferential compression. Advances in repair techniques have demonstrated promising clinical outcomes, and the ability to restore and preserve the meniscus in pathologies previously deemed irreparable. Further research to determine the optimal surgical technique for specific tear patterns, as well as rehabilitation protocols for meniscus pathology with concomitant ACL injury, is warranted.

Keywords: Meniscus tear, Meniscal repair, Anterior cruciate ligament injury, Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Lateral meniscal oblique radial tear of the posterior horn, Meniscal ramp lesion

Introduction

The menisci and the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) play important roles in knee stability to ensure smooth joint function. The central role of the ACL is promoting anterior–posterior knee stability as well as rotational stability [1]. The menisci are crescent-shaped cartilaginous structures that have been recognized as critical secondary stabilizers, with the medial meniscus serving as a restraint to anteriorly directed forces and the lateral meniscus limiting rotational torque such as during a pivoting maneuver [2, 3].

Meniscus injuries often accompany ACL tears and can occur concurrently or develop subsequently over time. ACL deficiency disrupts normal knee kinematics resulting in excessive joint load and an increased likelihood of meniscal damage [4–7]. Demonstrating this point, Sanders et al. found that nonoperative treatment or delayed reconstruction of ACL tears significantly increased the likelihood of a secondary meniscal tear. Additionally, these patients were significantly more likely to have progression of osteoarthritis and undergo subsequent total knee arthroplasty [7].

Nevertheless, meniscus pathology with concomitant ACL tears presents a significant clinical challenge. While the success of ACL reconstructions (ACLRs) has been well-documented in the literature [8, 9], the management of concomitant meniscal injuries continues to be controversial. The purpose of this review is to summarize current clinical knowledge on the prevalence and types of meniscal pathology seen with concomitant ACL tears, as well as surgical techniques, clinical outcomes, and rehabilitation following operative management of these pathologies.

Epidemiology

The ACL is the most injured ligament in the knee with the reported incidence of ruptures in the United States being approximately 68.6 per 100,000 annually [10]. Although not clearly defined, studies have shown a high incidence of concomitant meniscal pathology. A recent study analyzing the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register with close to 18,000 ACLRs found that 53.9% of patients had one or more concomitant intra-articular injuries with 25.2% and 21.4% of patients having medial and lateral meniscus pathology, respectively [11]. Similarly, Granan et al. compared intraoperative findings of patients who underwent ACLR in the Kaiser Permanente Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Registry and the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry. The authors found that in the Kaiser Permanente Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Registry, 62.7% of primary ACLRs had meniscus pathology with the medial and lateral meniscus being affected 41.0% and 38.5% of the time, respectively. In the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry, meniscal pathology was present 48.5% of the time during primary ACLRs with medial and lateral meniscus tears being present 30.6% and 24.1% of the time, respectively [12]. In the pediatric population, Perkins et al. studied 453 patients who underwent ACL reconstruction. Fifty-eight percent had a meniscal tear with increasing age and body mass index being independent risk factors for concomitant meniscal pathology [13•]. Likewise, a separate study showed a higher likelihood of concurrent ACL and medial meniscus injuries in patients over the age of 30 as well as a decreased rate of repairable meniscal lesions [14].

While most studies have shown a higher incidence of medial meniscus pathology with ACL tears [11, 12, 15], Slauterbeck et al. demonstrated a higher percentage of injury to the lateral meniscus (52%) in comparison to medial meniscus (22%) [16]. Similarly, a separate study showed that male patients who are less than 30 years old and sustained a contact injury are at higher risk for concomitant ACL injuries and lateral meniscus tears [17]. The timing of ACL injury also affects the location of tears as acute ACL injuries are more commonly associated with lateral meniscus injuries while chronic ACL deficiency is typically associated with medial meniscus pathology [18].

The timing of ACLR plays a pivotal role in development of secondary meniscal pathology [7]. Hagmeijer et al. found that in 1,398 primary ACL injuries, significantly lower rates of meniscal pathology were seen in patients who underwent acute ACLR within 6 months (7%) compared to those who underwent delayed surgical management (33%, p < 0.01) or nonoperative treatment (19%, p < 0.01) [15]. Similarly, a separate study showed that the incidence of medial meniscus tears was significantly higher in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction 3 months after their initial injury [19]. Thus, there is a high incidence of both medial and lateral meniscal pathology found concurrently with ACL tears, especially in patients with delayed reconstruction.

Unique Tear Types and Patterns

It is well-established that meniscus injury or deficiency impacts meniscal function and can accelerate degenerative processes in the knee. For this reason, meniscus repair is considered, if possible, to preserve meniscal tissue and potentially delay the development of future osteoarthritis. The pattern of meniscus tear guides management. Some tear patterns are more amenable to surgical repair than others. In the setting of concomitant ACL injury, a different variety of meniscus tear types can be encountered than in knees with isolated meniscus injury alone [20•].

Simple Tears

Simple tears of the meniscus do occur with concomitant ACL injury. These tear types include vertical (longitudinal), horizontal, and oblique (flap) tears.

Vertical tears typically occur in the vascular peripheral third of the meniscus and separate the meniscus into inner and outer fragments. Complete or incomplete small peripheral vertical tears < 10 mm in size can be considered stable and heal with non-operative treatment. Vertical tears greater than 10 mm are considered unstable and are considered the “gold standard” indication for meniscus healing and repair [21]. Vertical tears with a greater displacement of the tear edges into a central flap are considered bucket handle tears. These tears frequently result from trauma and are associated with concurrent ACL injury [21].

In contrast, horizontal tears are generally degenerative in nature and are oriented parallel with the tibial plateau, separating the meniscus into superior and inferior fragments. While horizontal tears had long been associated with poor healing, they have in fact been associated with a relatively high repair success rate (77.8%) [22].

Radial Tears

Radial tears disrupt the circumferential collagen fibers by transecting the meniscus from the inner free edge to the periphery. As a result, increased hoop stress leads to increased tibiofemoral contact pressure and degenerative transformation [23]. While radial tears were historically considered irreparable and managed by partial meniscectomy, more extensive radial tears that extend across the entire width of the meniscus are increasingly repaired. In fact, radial tear repair has been found to recover the contact pressure to a near native knee state [23].

Meniscal Root Tears

Meniscal root integrity is critical for the resistance of hoop stress during axial loading [24]. In the case of root disruption, there is an increase in articular cartilage contact pressure and an associated acceleration in degenerative disease [25]. Furthermore, Krych et al. demonstrated that meniscus root tears have high rates of meniscus extrusion, which has been shown to be a predictor of early osteoarthritic changes [25]. Biomechanical studies have shown that repair of medial and lateral root tears improve loading conditions and resist meniscal subluxation similar to that of the native knee [26, 27]. When medial meniscus posterior horn root tears are managed nonoperatively or with partial meniscectomy, Krych et al. found that there is an increased progression to arthritis with poor clinical outcomes and a high conversion rate to total knee arthroplasty [25].

In a review of 141 root tears, Krych et al. determined that compared with medial meniscus root tears, lateral meniscus root tears occur in younger male patients with lower body mass index, less cartilage degeneration, less extrusion on MRI, and are more commonly concurrent with a ligamentous injury. While good to excellent outcomes were observed following both medial and lateral meniscus root repair, lateral meniscus root tears had overall better results after repair. The authors suggested that this disparity may be secondary to differences in injury and patient characteristics.

Tears of the Lateral Meniscus

Tears involving the lateral meniscus are more generally found with concomitant acute ACL injuries [17, 28•, 29]. In a retrospective review of 600 patients with acute ACL disruption, 31% had a lateral meniscal injury [25].

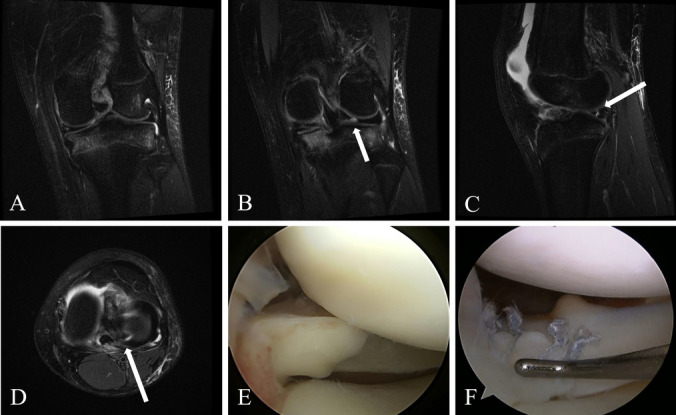

The most common lateral meniscus tear in the setting of acute ACL injury was a lateral meniscal oblique radial tear of the posterior horn (LMORT), with a prevalence between 12–15% (Fig. 1) [25, 28•, 30••]. Krych et al. described a four-tier LMORT classification system for LMORTs based on tear severity and distance from the root [25]. Type 1 (1.1–9.9%) is defined as a partial-thickness radial oblique tear that originates < 10 mm from the posterior root attachment [25, 30••]. Type 2 (12.7–14.7%) is described as full-thickness radial oblique tears that originate < 10 mm from the posterior root attachment without involving the root itself. Type 3 lesions (2.6%-29.6%) are characterized by incomplete, radial oblique tears that originate ≥ 10 mm from the meniscal root and extend towards the posterior root attachment without extending through the posterior rim to the meniscofemoral ligament. Finally, LMORT Type 4 lesions (32.6%-47.9%) are complete, radial oblique tears that originate ≥ 10 mm from the posterior root attachment and extend through the posterior rim and to the meniscofemoral ligament [25].

Fig. 1.

Acute ACL tear with concomitant LMORT in a 21-year-old female collegiate soccer player. A) Coronal T2-weighted MRI demonstrating complete ACL tear. B) Coronal, C) sagittal, and D) axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrating lateral meniscus tear (white arrows). E) Arthroscopic image identifying the tear as a LMORT. F) Arthroscopic image demonstrating suture repair of the LMORT. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament. LMORT, lateral meniscal oblique radial tear of the posterior horn. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Cadaveric studies have characterized the biomechanical consequences of type 3 and type 4 LMORT lesions on joint stability and meniscal function. Smith et al. found that these advanced lesions with concomitant ACL injury increased anterior laxity on both anterior drawer and pivot shift tests when compared with an isolated ACL injury, as well as increased lateral meniscal extrusion [31••]. Such findings emphasize the importance of diagnosing and managing these lesions at the time of ACL reconstruction [31••].

Lateral meniscus posterior root tears (LMPRT), also termed posterior root tears of the lateral meniscus, are also common lateral meniscus tears identified in an estimated 14% of patients with ACL injuries [29]. Biomechanically, cadaver studies have determined that LMPRTs increase rotational knee laxity compared with isolated ACL injury [32–35].

Tears of the Medial Meniscus

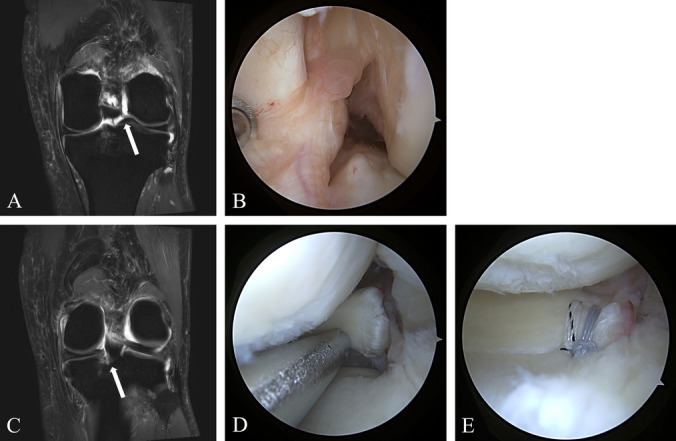

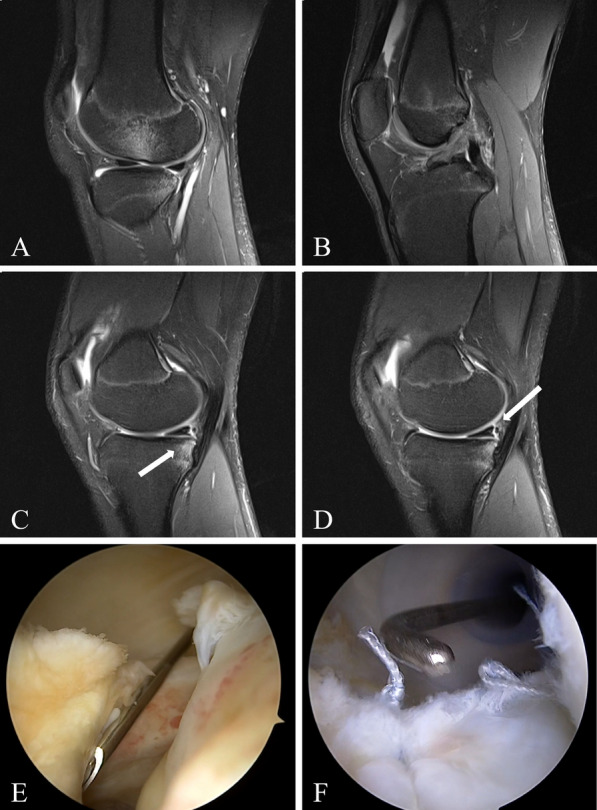

In contrast to tears of the lateral meniscus, tears of the medial meniscus are generally found in the setting of chronically ACL-deficient knees. Such tears include medial meniscus posterior root tears (Fig. 2) and ramp lesions of the medial meniscus (Fig. 3). It is thought that these tears likely occur secondary to post-traumatic knee instability.

Fig. 2.

A) Coronal T2-weighted MRI and B) arthroscopic image demonstrating complete ACL deficiency (white arrow). C) Coronal T2-weighted MRI and D) arthroscopic image demonstrating complete medial meniscus posterior horn root tear (white arrow). E) Arthroscopic image demonstrating a transtibial root repair. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Fig. 3.

Acute ACL tear with concomitant meniscal ramp lesion in a 19-year-old male sustained from a contact injury. A) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI demonstrating bony contusions at the sulcus terminalis and posterior lateral tibial plateau, and B) sagittal T2-weighted MRI demonstrating complete ACL rupture. C-D) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI and E) arthroscopic image demonstrating a meniscal ramp lesion (white arrows). F) Arthroscopic image demonstrating suture repair of the ramp lesion. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Ramp lesions are characterized by the vertical disruption of the peripheral meniscocapsular attachments of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus [36•, 37]. They present as a superior meniscocapsular ligament tear, inferior meniscotibial ligament tear, or both. Ramp lesions have been reported in 8% to 42% of all ACL tears [20•, 38, 39•]. This prevalence is likely an underestimate given that nearly 40% of ramp lesions can be missed during a standard anterior arthroscopic view [40]. These tears are more visible through transcondylar (modified Gillquist) view while the repair is completed through a posteromedial portal. Klein and Solomon report on the need to maintain a high level of suspicion for medial meniscus ramp lesions on pre-operative MRI in the setting of posteromedial tibial plateau bone bruising [41]. In a cohort of 201 children and adolescents undergoing ACL reconstruction, 14% were found to have a ramp lesion intraoperatively [42••]. The primary predictor of a ramp lesion was the presence of femoral condylar chondromalacia intraoperatively and posteromedial tibial marrow edema on MRI. All patients with both risk factors had a ramp lesion confirmed intraoperatively; patients with neither risk factor had a 2% rate of ramp lesion, and those with either of the aforementioned risk factors had a 24% rate of ramp lesion [42••].

The biomechanical impact of ramp lesions is not well understood. However, in one cadaver study, ACL deficient knees with concomitant ramp lesions were associated with increased external rotation and anterior translation; only restoration of both pathologies restored native knee biomechanics [43]. It is believed that unstable ramp lesions at the time of ACL reconstruction could increase graft failure and secondary osteoarthritis. These findings underscore the importance of restoring knee stability when treating ligamentous injuries [41].

Surgical Techniques

Surgical decision making for meniscal pathology depends on tear etiology, tear pattern, tear location, and concomitant injuries, such as concomitant ACL injury. Key principles guide meniscal repair in adolescents and adult patients alike [44, 45]. Surgical indications include acute tears, chronic symptoms, and younger age; absolute contraindications include osteoarthritis and untreated instability. Hevesi et al. describe the “ABCs of meniscus repair,” which include: 1) anatomic reduction, 2) biologic preparation and augmentation, and 3) circumferential compression [45]. Recent advances in meniscal repair with concomitant ACL reconstruction effectively implement the ABCs of meniscus repair to preserve the meniscus, reapproximate native joint biomechanics, and reduce long term risk of osteoarthritis [45]. Excluding root repairs, methods of repair are typically grouped into inside-out, outside-in, and all-inside techniques, as well as hybrids of these techniques [46•]. Additional repair techniques, including the release of marrow elements during concurrent ACL reconstruction (“marrow venting”) are known to improve meniscus repair outcomes as well [47].

Inside-Out

The inside-out technique remains the gold standard for most meniscus tear patterns due to its versality and cost-efficiency. This approach is particularly effective with larger tears and tears involving the posterior horn or body [48•]. While historically utilized for vertical and bucket-handle tears, the inside-out approach has been increasingly used for more complex radial tears and tears previously deemed irreparable [49, 50]. Advantages of the inside-out approach include use of smaller diameter needles that promote preservation of the structural integrity of the meniscus, decreased risk of tear propagation, and better arthroscopic access [51]. Furthermore, the inside-out technique allows for the use of an increased number of sutures as well as flexibility of suture placement, which can facilitate a stronger meniscal construct [52]. Disadvantages of the inside-out approach include greater technical difficulty in the use of an open incision and extraarticular dissection, more reliance on skilled assistants, and greater care to avoid neurovascular injury during needle retrieval [53]. Marigi et al. describe protection of the vulnerable neurovascular structures with use of a posteromedial or posterolateral incision with careful dissection, retractor placement, and suture retrieval [48•].

All-Inside

Since its initial introduction in 1991 by Morgan [54], the all-inside technique has grown in popularity in the repair of a variety of tear patterns, including radial, vertical, and horizontal meniscal tears [46•]. In comparison to the inside-out approach, the all-inside technique can avoid then associated risks of neurovascular damage in certain cases [46•]. Furthermore, all-inside repairs have demonstrated reduced operative time and earlier post-operative recovery compared to the inside-out repair [55]. Both all-inside and inside-out repairs have demonstrated excellent healing in LMORTs; however, these findings are limited to a few studies [56]. Woodmass et al. and Cavendish et al. describe the powerful use of circumferential compression sutures through an all-inside approach to repair horizontal cleavage tears. By providing uniform compression of the superior and inferior leaflets, this technique has been shown to promote meniscal healing and demonstrate a high load to failure [57, 58].

The primary disadvantage to all-inside approaches is the reliance on special devices and implants. With these devices, fixation is achieved with intraarticular knots or extraarticular implants (such as, anchors and buttons), leading to increased surgical costs and a variety of implant-related postoperative complications [46•, 48•]. Such complications include articular cartilage injury, device migration, device failure, and local soft tissue irrigation and swelling [46•]. Of note, Malinowski et al. described an all-inside approach that does not require special implants, but rather uses a suture hook with simple nonabsorbable vertical sutures for vertical longitudinal tears of the medial meniscus [59]. Also notable is the fact that all-inside devices are generally larger in needle diameter than their inside-out counterparts.

Outside-In

In contrast to the inside-out and all-inside repair techniques, outside-in techniques are less commonly used and are typically reserved for mid-body or anterior third meniscal tears that are more difficult to visualize and manipulate with traditional arthroscopic portals [48•]. However, Steiner et al. have described a technique to repair complete radial tears of the lateral meniscus to effectively reduce the meniscus and restore the native anatomy [60].

Root Repairs

There are two main repair techniques described for root repairs: 1) suture anchors (direct fixation) and 2) sutures pulled through a tibial tunnel [61]. In a prospective clinical study of 47 transtibial root repairs for medial and lateral posterior meniscal root tears, Krych et al. demonstrated significant improved clinical outcomes at 2 years postoperatively [62•]. With transtibial meniscus root repairs with concomitant ACL reconstruction, great care needs to be taken to avoid tunnel coalition or convergence with posterior placement of the tibial tunnel [61, 63•]. Based on their cadaveric study, Gursoy et al. recommend reducing convergence by reorienting the meniscus root tunnels to travel parallel to the ACL tunnel on the sagittal plane [63•].

Meniscal Ramp Lesion Repair

As discussed, meniscal ramp lesions involving the peripheral capsular attachment of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus are commonly encountered in the setting of ACL deficiency. Restoration of knee stability and protection of the ACL graft warrants identification and repair of these often “hidden” lesions [64]. Buyukdogan et al. describe a trans-septal portal technique to effectively visualize the ramp lesion and achieve a satisfactory vertical suture repair [64]. The authors emphasize the care required to ensure safe establishment of the trans-septal portal, recommending the use of transillumination of the posterior compartment and the use of bony landmarks to avoid injury to the popliteal artery [64, 65].

Clinical Outcomes

Meniscus pathology with concomitant ACL injury was historically treated with meniscectomy which led to poor outcomes, increased pain, and osteoarthritic progression [66–68]. Cohen et al. found that all patients who underwent ACL reconstruction with simultaneous medial or lateral meniscectomy had osteoarthritis 10 to 15 years after surgery [68]. Meniscectomy can also significantly worsen anterior translation, pivot shift, and meniscal extrusion [31••]. In contrast, a systematic review found ACLR with combined meniscectomy had satisfactory short-term patient-reported outcomes at two-year follow-up and low reoperation rates. However, ACLR with combined meniscal repair had better long-term patient-reported outcomes and decreased anterior knee joint laxity [69].

In comparison to meniscectomy, meniscus repair not only demonstrates superior clinical outcomes [69–71] but also restores translational stability and reduces meniscal extrusion [72]. While meniscus resection ultimately leads to end-stage osteoarthritis, meniscus repair has shown favorable long-term joint preservation. At a minimum 10-year follow-up, Wright et al. demonstrated that medial and lateral meniscus repair with concomitant ACLR required repeat surgical intervention only 12% and 16% of the time, respectively [73•]. Similarly, at a mean follow-up of 16.6 years, only 28% of patients underwent revision surgery in the pediatric and adolescent population [74].

Clinical outcomes of ACLR with concomitant meniscal repair are comparable to each isolated procedure [70, 75•]. Notably, Wasserstein et al. found ACLR performed in conjunction with meniscal repair resulted in a 7% absolute and 42% relative risk reduction of reoperation at 2 years in comparison to meniscal repair alone. This may be attributed to bone marrow stimulation through the drilling of bone tunnels for ACLR [76]. DePhillipo et al. compared isolated ACLR and ACLR with simultaneous meniscus repair and found no significant differences across eight different postoperative outcomes scores between both groups [77]. In contrast, a separate study found that Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores were significantly lower for patients who underwent simultaneous ACLR and lateral meniscus repair. However, this did not reach the minimal clinically important difference threshold and thus may not be clinically relevant [78].

Although clinical outcomes were comparable, radiological outcomes may be less congruent. Patients who underwent concomitant ACLR and meniscus repair had worse articular damage on MRI two to three years following surgery in comparison to those who solely underwent ACLR [79•]. Concomitant surgery with lateral meniscus repair also had greater cartilage deterioration in the lateral tibial plateau and increased sagittal meniscal extrusion at a mean follow-up of 3.4 years [56]. However, these cartilage defects may have been the result of the index injury. It is important to note that with the number of revision ACLRs continuing to increase [80], the odds of meniscal and chondral injuries at the time of revision surgery are higher after prior concomitant ACLR and meniscus repair [81••].

The impact of the type of meniscus tear on outcomes remains debatable. Wu et al. performed a matched cohort analysis comparing the outcomes after radial and bucket-handle meniscus repairs, revealing no significant differences in reoperation rates, as well as pre- and postoperative changes in VAS and IKDC scores between the two groups [82]. Similarly, Gan et al. compared outcomes after complex, longitudinal, horizontal, and radial meniscus repairs. The authors found similar postoperative IKDC and Tegner scores across the different tear groups with no difference in outcomes scores based on location of meniscal pathology (body or posterior horn) [83]. In contrast, surgical repair of complex and bucket-handle meniscus tears with ACLR have been found to be negative prognostic factors for treatment failure in pediatric and adolescent patients [84].

Similarly, the impact of concomitant ACLR and meniscus repair on knee kinematics remains inconclusive, given conflicting results across multiple studies [85•, 86•]. Grassi et al. showed significantly increased tibial internal rotation after concomitant ACLR and medial meniscus repair [85•] while Chiba et al. showed no significant difference in rotatory knee instability after the same procedure. On the other hand, Chiba et al. also demonstrated significantly increased rotatory knee instability after concomitant ACLR and lateral meniscus repair [86•] while Smith et al. found ACLR and lateral meniscal repair effectively restored knee kinematics [31••]. Given the diverse array of treatment options for both meniscus repairs and ACLRs, future studies are necessary to elucidate the impact of various surgical approaches and types of meniscus tears on long-term biomechanical, clinical, and radiological outcomes.

Rehabilitation

There is a lack of consensus for postoperative rehabilitation after concomitant meniscus repair and ACLR. Differing surgical techniques and location of meniscus lesions may further affect the rehabilitation protocol [87]. For meniscal repair, range of motion and weight-bearing are typically restricted shortly after surgery and are slowly progressed [88]. In contrast, early weight-bearing and full range of motion are promoted after ACLR and have shown to be beneficial [89]. As a result, the restrictive protocol after meniscus repair may affect the rehabilitation process of the ACLR. However, Wenning et al. performed a matched cohort analysis of patients who underwent isolated ACLR and ACLR with meniscal repair. At six months postoperatively, both groups had similar flexion and extension strength suggesting meniscus repair does not affect recovery of limb strength [87]. Similarly, Casp et al. demonstrated that weight-bearing and range of motion restrictions after concurrent ACLR and meniscal repair do not result in loss of strength or worse clinical outcomes at 6 months postoperatively in comparison to ACLR alone [90•]. While there is substantial heterogeneity in rehabilitation protocols, some believe it may not be necessary to modify postoperative ACLR protocols for those undergoing concomitant ACLR and meniscus repair. However, these studies are outdated [91, 92]. At our institution, we adopt an integrated approach to ACLR and meniscus repair rehabilitation protocols (Table 1).

Table 1.

Standard and complex meniscus repair rehabilitation protocols

| Phase | Goals | Precautions/Restrictions | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Weeks 0–4 Weeks 0–6 |

• Protect surgical site • PRICE principles • Active ROM: 0–90 degree • Reduce muscle atrophy • Reduce swelling • Decrease pain and inflammation |

• ROM: 0–90 degrees (progress to as tolerated at 4 weeks with surgeon approval) • PWB with the knee in full extension using crutches (TWB with the knee in full extension using crutches. PWB at 4 weeks with surgeon approval) • Hinged knee brace must be on at all times when walking (locked in extension) |

• PRICE Cryotherapy: 5–7 times per day Compression with TubiGrip/TEDS • ROM (limited to 0–90 degrees) Heel slides Prone knee hangs/Supine knee extension with towel under ankle Patella mobilizations • Quadriceps recruitment • Global lower extremity isometric/proximal hip strengthening • Gait training with crutches |

|

Weeks 4–8 Weeks 6–12 |

• Discontinue hinged knee brace • Full ROM • Reduce atrophy/progress strengthening • Reduce swelling • Normalize gait • SLR without extensor lag |

• ROM: as tolerated • Progress to WBAT (wean crutches) • No loading at knee flexion angles > 90 degrees (16 weeks) • No jogging or sport activity • Avoid painful activities/exercises • Discontinue hinged knee brace at Week 6 |

• Gait training from WBAT to independent • Core stabilization exercises • Neuromuscular re-education • Global lower extremity strengthening Limit deep knee flexion angles > 90 degrees Begin functional strengthening exercises (bridge, mini-squat, step up) • Double limb and single limb balance/proprioception • Aerobic training: Walking program when walking with normal gait mechanics Stationary bike |

|

Weeks 8–16 Weeks 12–18 |

• No effusion • Full ROM • Increase functional lower extremity strengthen • Return to activity as tolerated • Initiate return to running program • Initiate basic plyometrics |

• No loading at knee flexion angles > 90 degrees (16 weeks) • Avoid painful activities/exercises • No running until Week 12 (Week 14) and cleared by surgeon • No jogging on painful or swollen knee • No plyometric exercises until week 14 (16 weeks) and cleared by surgeon |

• Aerobic training Begin non-impact aerobic training (elliptical/Stairmaster) • Increase loading capacity for lower extremity strengthening exercises • Continue balance/proprioceptive training • Week 12 (Week 14): begin return to running program • Week 16: begin low level plyometric and agility training |

|

Weeks 16 + Weeks 18–24 |

• Full ROM • Functional strengthening • Return to sport/activity |

• Return to sport 4–8 months (6–9 months) post-operatively with surgeon approval |

• Gradually increase lifting loads focusing on form, control, and tissue tolerance • Progress as tolerated: ROM, strengthen, endurance, proprioception/balance, agility, sport specific skills |

Reproduced from the Standard Meniscus Repair Rehabilitation Protocol and the Complex Meniscus Repair Rehabilitation Protocol developed by Mayo Clinic, Department of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine

Bold indicates deviation from the standard meniscus repair rehabilitation protocol to optimize rehabilitation for complex meniscus repairs. Complex meniscus repairs include radial, root, or complex repairs, as well as concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

PRICE protect, rice, ice, compression, elevation, ROM range of motion, WBAT weightbearing as tolerated, PWB partial weightbearing

Current rehabilitation guidelines for ACLR and meniscus repair rely on numerous studies with low levels of evidence [93, 94]. Additionally, many of the pertinent randomized controlled trials have limited sample sizes [94]. As a result, high quality clinical trials with substantial sample sizes are needed to help develop consensus recommendations and guide clinical practice.

Conclusion

There has been a substantial increase in recent publications demonstrating the importance of meniscus repair at the time of ACL repair or reconstruction to restore knee biomechanics and reduce the risk of progressive osteoarthritic degeneration. Through these studies, there has been a growing understanding of the meniscus tear patterns commonly identified or potentially missed during ACL reconstruction. Surgical management of meniscal pathology with concomitant ACL injury implements the same principles as utilized in the setting of isolated meniscus repair alone: anatomic reduction, biologic preparation and augmentation, and circumferential compression. Advanced repair techniques have demonstrated promising clinical outcomes, and the ability to restore and preserve the meniscus in pathologies previously deemed irreparable. Further research to determine the optimal surgical technique for specific tear patterns, as well as rehabilitation protocols for meniscus pathology with concomitant ACL injury, are warranted.

Author Contributions

A.F. and A.T. designed and implemented the study. A.F. and S.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures. A.K. conceptualized the study and provided all figures. All authors interpreted the relevant studies and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Aliya Feroe declares that she has no conflict of interest. Sean Clark declares that he has no conflict of interest. Mario Hevesi has served as a paid consultant for DJO Enovis. Kelechi Okoroha has served as a paid consultant for Arthrex Inc and Smith & Nephew. Daniel Saris has served as a paid consultant for NewClip. Aaron Krych has received research support from Aesculap/B.Braun, has served as a paid consultant for and received IP royalties from Arthrex Inc, and has served on the editorial board for Springer. Adam Tagliero declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Domnick C, Raschke MJ, Herbort M. Biomechanics of the anterior cruciate ligament: Physiology, rupture and reconstruction techniques. World J Orthop. 2016;7(2):82–93. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy IM, Torzilli PA, Warren RF. The effect of medial meniscectomy on anterior-posterior motion of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(6):883–888. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198264060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoshino Y, Miyaji N, Nishida K, Nishizawa Y, Araki D, Kanzaki N, et al. The concomitant lateral meniscus injury increased the pivot shift in the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(2):646–651. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomihara T, Hashimoto Y, Takahashi S, Taniuchi M, Takigami J, Tsumoto S, et al. Analyses of associated factors with concomitant meniscal injury and irreparable meniscal tear at primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young patients. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2023;32:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.asmart.2023.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhadia AM, Inacio MC, Maletis GB, Csintalan RP, Davis BR, Funahashi TT. Are meniscus and cartilage injuries related to time to anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1894–1899. doi: 10.1177/0363546511410380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR., Jr Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate-deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1997;26(1):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders TL, Kremers HM, Bryan AJ, Fruth KM, Larson DR, Pareek A, et al. Is Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Effective in Preventing Secondary Meniscal Tears and Osteoarthritis? Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(7):1699–1707. doi: 10.1177/0363546516634325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ardern CL, Sonesson S, Forssblad M, Kvist J. Comparison of patient-reported outcomes among those who chose ACL reconstruction or non-surgical treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(5):535–544. doi: 10.1111/sms.12707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cupido C, Peterson D, Sutherland MS, Ayeni O, Stratford PW. Tracking patient outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physiother Can. 2014;66(2):199–205. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2013-19BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders TL, Maradit Kremers H, Bryan AJ, Larson DR, Dahm DL, Levy BA, et al. Incidence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Reconstruction: A 21-Year Population-Based Study. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1502–1507. doi: 10.1177/0363546516629944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahldén M, Samuelsson K, Sernert N, Forssblad M, Karlsson J, Kartus J. The Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register: a report on baseline variables and outcomes of surgery for almost 18,000 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2230–2235. doi: 10.1177/0363546512457348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granan LP, Inacio MC, Maletis GB, Funahashi TT, Engebretsen L. Intraoperative findings and procedures in culturally and geographically different patient and surgeon populations: an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction registry comparison between Norway and the USA. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(6):577–582. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.741451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins CA, Christino MA, Busch MT, Egger A, Murata A, Kelleman M, et al. Rates of Concomitant Meniscal Tears in Pediatric Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries Increase With Age and Body Mass Index. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(3):2325967120986565. doi: 10.1177/2325967120986565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erard J, Cance N, Shatrov J, Fournier G, Gunst S, Ciolli G, et al. Delaying ACL reconstruction is associated with increased rates of medial meniscal tear. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(10):4458–4466. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagmeijer MH, Hevesi M, Desai VS, Sanders TL, Camp CL, Hewett TE, et al. Secondary Meniscal Tears in Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Relationship Among Operative Management, Osteoarthritis, and Arthroplasty at 18-Year Mean Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(7):1583–1590. doi: 10.1177/0363546519844481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slauterbeck JR, Kousa P, Clifton BC, Naud S, Tourville TW, Johnson RJ, et al. Geographic mapping of meniscus and cartilage lesions associated with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2094–2103. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.H.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feucht MJ, Bigdon S, Bode G, Salzmann GM, Dovi-Akue D, Südkamp NP, et al. Associated tears of the lateral meniscus in anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors for different tear patterns. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015;10:34. doi: 10.1186/s13018-015-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cipolla M, Scala A, Gianni E, Puddu G. Different patterns of meniscal tears in acute anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and in chronic ACL-deficient knees. Classification, staging and timing of treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3(3):130–4. doi: 10.1007/bf01565470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razi M, Salehi S, Dadgostar H, Cherati AS, Moghaddam AB, Tabatabaiand SM, et al. Timing of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Incidence of Meniscal and Chondral Injury within the Knee. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(Suppl 1):S98–s103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magosch A, Mouton C, Nührenbörger C, Seil R. Medial meniscus ramp and lateral meniscus posterior root lesions are present in more than a third of primary and revision ACL reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29(9):3059–67. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozeki N, Seil R, Krych AJ, Koga H. Surgical treatment of complex meniscus tear and disease: state of the art. J ISAKOS. 2021;6(1):35–45. doi: 10.1136/jisakos-2019-000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurzweil PR, Lynch NM, Coleman S, Kearney B. Repair of horizontal meniscus tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(11):1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsubara H, Okazaki K, Izawa T, Tashiro Y, Matsuda S, Nishimura T, et al. New suture method for radial tears of the meniscus: biomechanical analysis of cross-suture and double horizontal suture techniques using cyclic load testing. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(2):414–418. doi: 10.1177/0363546511424395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krych AJ, Bernard CD, Kennedy NI, Tagliero AJ, Camp CL, Levy BA, et al. Medial Versus Lateral Meniscus Root Tears: Is There a Difference in Injury Presentation, Treatment Decisions, and Surgical Repair Outcomes? J Arthrosc. 2020;36(4):1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krych AJ, LaPrade MD, Cook CS, Leland D, Keyt LK, Stuart MJ, et al. Lateral Meniscal Oblique Radial Tears Are Common With ACL Injury: A Classification System Based on Arthroscopic Tear Patterns in 600 Consecutive Patients. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(5):2325967120921737. doi: 10.1177/2325967120921737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaPrade CM, Jansson KS, Dornan G, Smith SD, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF. Altered Tibiofemoral Contact Mechanics Due to Lateral Meniscus Posterior Horn Root Avulsions and Radial Tears Can Be Restored with in Situ Pull-Out Suture Repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(6):471–479. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.L.01252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schillhammer CK, Werner FW, Scuderi MG, Cannizzaro JP. Repair of Lateral Meniscus Posterior Horn Detachment Lesions: A Biomechanical Evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2604–2609. doi: 10.1177/0363546512458574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel AV, Krych AJ, Smith PA. The Lateral Meniscus Oblique Radial Tear (LMORT) Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(7):306–15. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forkel P, Reuter S, Sprenker F, Achtnich A, Herbst E, Imhoff A, et al. Different patterns of lateral meniscus root tears in ACL injuries: application of a differentiated classification system. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):112–118. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon YS, Alsomali K, Yang SW, Lee OJ, Kang B, Wang JH. Posterior Horn Lateral Meniscal Oblique Radial Tear in Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Incidence and Outcomes After All-Inside Repair: Clinical and Second-Look Arthroscopic Evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(14):3796–804. doi: 10.1177/03635465221126506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith PA, Bezold WA, Cook CR, Krych AJ, Stuart MJ, Wijdicks CA, et al. Kinematic Analysis of Lateral Meniscal Oblique Radial Tears in Anterior Cruciate Ligament-Reconstructed Knees: Untreated Versus Repair Versus Partial Meniscectomy. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(9):2381–9. doi: 10.1177/03635465221102135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forkel P, von Deimling C, Lacheta L, Imhoff FB, Foehr P, Willinger L, et al. Repair of the lateral posterior meniscal root improves stability in an ACL-deficient knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(8):2302–2309. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4949-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank JM, Moatshe G, Brady AW, Dornan GJ, Coggins A, Muckenhirn KJ, et al. Lateral Meniscus Posterior Root and Meniscofemoral Ligaments as Stabilizing Structures in the ACL-Deficient Knee: A Biomechanical Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(6):2325967117695756. doi: 10.1177/2325967117695756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lording T, Corbo G, Bryant D, Burkhart TA, Getgood A. Rotational Laxity Control by the Anterolateral Ligament and the Lateral Meniscus Is Dependent on Knee Flexion Angle: A Cadaveric Biomechanical Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(10):2401–2408. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5364-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shybut TB, Vega CE, Haddad J, Alexander JW, Gold JE, Noble PC, et al. Effect of lateral meniscal root tear on the stability of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):905–911. doi: 10.1177/0363546514563910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siboni R, Pioger C, Jacquet C, Mouton C, Seil R. Ramp Lesions of the Medial Meniscus. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(5):173–81. doi: 10.1007/s12178-023-09834-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zappia M, Sconfienza LM, Guarino S, Tumminello M, Iannella G, Mariani PP. Meniscal ramp lesions: diagnostic performance of MRI with arthroscopy as reference standard. La Radiol Med. 2021;126(8):1106–16. doi: 10.1007/s11547-021-01375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bumberger A, Koller U, Hofbauer M, Tiefenboeck TM, Hajdu S, Windhager R, et al. Ramp lesions are frequently missed in ACL-deficient knees and should be repaired in case of instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(3):840–854. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brophy RH, Steinmetz RG, Smith MV, Matava MJ. Meniscal Ramp Lesions: Anatomy, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(6):255–62. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonnery-Cottet B, Conteduca J, Thaunat M, Gunepin FX, Seil R. Hidden lesions of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: a systematic arthroscopic exploration of the concealed portion of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):921–926. doi: 10.1177/0363546514522394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klein E, Solomon D. Editorial Commentary: Arthroscopy Is the Gold Standard for Diagnosis of Meniscal Ramp Lesions: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Also May Be Helpful. J Arthrosc. 2023;39(3):600–601. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollnagel KF, Pennock AT, Bomar JD, Chambers HG, Edmonds EW. Meniscal Ramp Lesions in Adolescent Patients Undergoing Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Significance of Imaging and Arthroscopic Findings. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(6):1506–12. doi: 10.1177/03635465231154600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mouton C, Magosch A, Pape D, Hoffmann A, Nührenbörger C, Seil R. Ramp lesions of the medial meniscus are associated with a higher grade of dynamic rotatory laxity in ACL-injured patients in comparison to patients with an isolated injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(4):1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05579-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tagliero AJ, Kennedy NI, Leland DP, Camp CL, Milbrandt TA, Stuart MJ, et al. Meniscus repairs in the adolescent population-safe and reliable outcomes: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28(11):3587–3596. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hevesi M, Krych AJ, Kurzweil PR. Meniscus Tear Management: Indications, Technique, and Outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(9):2542–2544. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golz AG, Mandelbaum B, Pace JL. All-Inside Meniscus Repair. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022;15(4):252–8. doi: 10.1007/s12178-022-09766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dean CS, Chahla J, Matheny LM, Mitchell JJ, LaPrade RF. Outcomes After Biologically Augmented Isolated Meniscal Repair With Marrow Venting Are Comparable With Those After Meniscal Repair With Concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(6):1341–1348. doi: 10.1177/0363546516686968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marigi EM, Till SE, Wasserburger JN, Reinholz AK, Krych AJ, Stuart MJ. Inside-Out Approach to Meniscus Repair: Still the Gold Standard? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2022;15(4):244–51. doi: 10.1007/s12178-022-09764-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karia M, Ghaly Y, Al-Hadithy N, Mordecai S, Gupte C. Current concepts in the techniques, indications and outcomes of meniscal repairs. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019;29(3):509–520. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2317-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pareek A, O’Malley MP, Levy BA, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Inside-Out Repair for Radial Meniscus Tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(4):e793–e797. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pace JL, Inclan PM, Matava MJ. Inside-out Medial Meniscal Repair: Improved Surgical Exposure With a Sub-semimembranosus Approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(2):e507–e517. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2020.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chahla J, Serra Cruz R, Cram TR, Dean CS, LaPrade RF. Inside-Out Meniscal Repair: Medial and Lateral Approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5(1):e163–e168. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smoak JB, Matthews JR, Vinod AV, Kluczynski MA, Bisson LJ. An Up-to-Date Review of the Meniscus Literature: A Systematic Summary of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(9):2325967120950306. doi: 10.1177/2325967120950306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morgan CD. The “all-inside” meniscus repair. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(1):120–125. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90093-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ardizzone CA, Houck DA, McCartney DW, Vidal AF, Frank RM. All-Inside Repair of Bucket-Handle Meniscal Tears: Clinical Outcomes and Prognostic Factors. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(13):3386–3393. doi: 10.1177/0363546520906141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsujii A, Yonetani Y, Kinugasa K, Matsuo T, Yoneda K, Ohori T, et al. Outcomes More Than 2 Years After Meniscal Repair for Radial/Flap Tears of the Posterior Lateral Meniscus Combined With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(12):2888–2894. doi: 10.1177/0363546519869955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woodmass JM, Johnson JD, Wu IT, Saris DBF, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Horizontal Cleavage Meniscus Tear Treated With All-inside Circumferential Compression Stitches. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(4):e1329–e1333. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cavendish PA, Coffey E, Milliron EM, Barnes RH, Flanigan DC. Horizontal Cleavage Tear Meniscal Repair Using All-Inside Circumferential Compression Sutures. Arthrosc Tech. 2023;12(8):e1319–e1327. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2023.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malinowski K, Góralczyk A, Hermanowicz K, LaPrade RF. Tips and Pearls for All-Inside Medial Meniscus Repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8(2):e131–e139. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steiner SRH, Feeley SM, Ruland JR, Diduch DR. Outside-in Repair Technique for a Complete Radial Tear of the Lateral Meniscus. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7(3):e285–e288. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woodmass JM, Mohan R, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Medial Meniscus Posterior Root Repair Using a Transtibial Technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(3):e511–e516. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krych AJ, Song BM, Nauert RF, 3rd, Cook CS, Levy BA, Camp CL, et al. Prospective Consecutive Clinical Outcomes After Transtibial Root Repair for Posterior Meniscal Root Tears: A Multicenter Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(2):23259671221079794. doi: 10.1177/23259671221079794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gursoy S, Perry AK, Brady A, Dandu N, Singh H, Vadhera AS, et al. Optimal Tibial Tunnel Placement for Medial and Lateral Meniscus Root Repair on the Anteromedial Tibia in the Setting of Anterior and Posterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction of the Knee. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(5):1237–44. doi: 10.1177/03635465221074312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buyukdogan K, Laidlaw MS, Miller MD. Meniscal Ramp Lesion Repair by a Trans-septal Portal Technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(4):e1379–e1386. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim SJ, Song HT, Moon HK, Chun YM, Chang WH. The safe establishment of a transseptal portal in the posterior knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(8):1320–1325. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery. Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):446–52. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shelbourne KD, Dersam MD. Comparison of partial meniscectomy versus meniscus repair for bucket-handle lateral meniscus tears in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(6):581–585. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cohen M, Amaro JT, Ejnisman B, Carvalho RT, Nakano KK, Peccin MS, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction after 10 to 15 years: association between meniscectomy and osteoarthrosis. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sarraj M, Coughlin RP, Solow M, Ekhtiari S, Simunovic N, Krych AJ, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with concomitant meniscal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(11):3441–3452. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips M, Rönnblad E, Lopez-Rengstig L, Svantesson E, Stålman A, Eriksson K, et al. Meniscus repair with simultaneous ACL reconstruction demonstrated similar clinical outcomes as isolated ACL repair: a result not seen with meniscus resection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(8):2270–2277. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-4862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH. Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(9):1275–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li M, Li Z, Li Z, Jiang H, Lee S, Huang W, et al. Transtibial pull-out repair of lateral meniscus posterior root is beneficial for graft maturation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):445. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright RW, Huston LJ, Haas AK. Ten-Year Outcomes of Second-Generation, All-Inside Meniscal Repair in the Setting of ACL Reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023;105(12):908–14. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.22.01196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tagliero AJ, Desai VS, Kennedy NI, Camp CL, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, et al. Seventeen-Year Follow-up After Meniscal Repair With Concomitant Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in a Pediatric and Adolescent Population. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(14):3361–3367. doi: 10.1177/0363546518803934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas B, de Villeneuve Florent B, Alexandre F, Martine P, Akash S, Corentin P, et al. Patients with meniscus posterolateral root tears repair during ACL reconstruction achieve comparable post-operative outcome than patients with isolated ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(8):3405–11. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wasserstein D, Dwyer T, Gandhi R, Austin PC, Mahomed N, Ogilvie-Harris D. A matched-cohort population study of reoperation after meniscal repair with and without concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):349–355. doi: 10.1177/0363546512471134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DePhillipo NN, Dornan GJ, Dekker TJ, Aman ZS, Engebretsen L, LaPrade RF. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Meniscus Ramp Repair. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(4):2325967120912427. doi: 10.1177/2325967120912427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaarre J, Herman ZJ, Persson F, Wållgren JO, Alentorn-Geli E, Senorski EH, et al. Differences in postoperative knee function based on concomitant treatment of lateral meniscal injury in the setting of primary ACL reconstruction. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):737. doi: 10.1186/s12891-023-06867-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Altahawi FF, Reinke EK, Briskin I, Cantrell WA, Flanigan DC, Fleming BC, et al. Meniscal Treatment as a Predictor of Worse Articular Cartilage Damage on MRI at 2 Years After ACL Reconstruction: The MOON Nested Cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(4):951–61. doi: 10.1177/03635465221074662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim D-H, Bae K-C, Kim D-W, Choi B-C. Two-stage revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surgery & Related Research. 2019;31(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s43019-019-0010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Persson F, Kaarre J, Herman ZJ, Olsson Wållgren J, Hamrin Senorski E, Musahl V, et al. Effect of Concomitant Lateral Meniscal Management on ACL Reconstruction Revision Rate and Secondary Meniscal and Cartilaginous Injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(12):3142–8. doi: 10.1177/03635465231194624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu IT, Hevesi M, Desai VS, Camp CL, Dahm DL, Levy BA, et al. Comparative Outcomes of Radial and Bucket-Handle Meniscal Tear Repair: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(11):2653–2660. doi: 10.1177/0363546518786035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gan JZ, Lie DT, Lee WQ. Clinical outcomes of meniscus repair and partial meniscectomy: Does tear configuration matter? J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2020;28(1):2309499019887653. doi: 10.1177/2309499019887653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krych AJ, Pitts RT, Dajani KA, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, Dahm DL. Surgical repair of meniscal tears with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients 18 years and younger. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):976–982. doi: 10.1177/0363546509354055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Grassi A, Agostinone P, Paolo SD, Lucidi GA, Pinelli E, Marchiori G, et al. Medial Meniscal Posterior Horn Suturing Influences Tibial Internal-External Rotation in ACL-Reconstructed Knees. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(7):23259671231177596. doi: 10.1177/23259671231177596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chiba D, Yamamoto Y, Kimura Y, Sasaki S, Sasaki E, Yamauchi S, et al. Concomitant Lateral Meniscus Tear is Associated with Residual Rotatory Knee Instability 1 Year after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Case-cohort Study. J Knee Surg. 2023;36(13):1341–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1757594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wenning M, Heitner AH, Mauch M, Gehring D, Ramsenthaler C, Paul J. The effect of meniscal repair on strength deficits 6 months after ACL reconstruction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(6):751–760. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03347-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O’Donnell K, Freedman KB, Tjoumakaris FP. Rehabilitation Protocols After Isolated Meniscal Repair: A Systematic Review. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(7):1687–1697. doi: 10.1177/0363546516667578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wright RW, Haas AK, Anderson J, Calabrese G, Cavanaugh J, Hewett TE, et al. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Rehabilitation: MOON Guidelines. Sports Health. 2015;7(3):239–243. doi: 10.1177/1941738113517855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Casp AJ, Bodkin SG, Gwathmey FW, Werner BC, Miller MD, Diduch DR, et al. Effect of Meniscal Treatment on Functional Outcomes 6 Months After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(10):23259671211031281. doi: 10.1177/23259671211031281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Barber FA, Click SD. Meniscus repair rehabilitation with concurrent anterior cruciate reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):433–437. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mariani PP, Santori N, Adriani E, Mastantuono M. Accelerated rehabilitation after arthroscopic meniscal repair: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Arthroscopy. 1996;12(6):680–686. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spang Iii RC, Nasr MC, Mohamadi A, DeAngelis JP, Nazarian A, Ramappa AJ. Rehabilitation following meniscal repair: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000212. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Culvenor AG, Girdwood MA, Juhl CB, Patterson BE, Haberfield MJ, Holm PM, et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament and meniscal injuries: a best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews for the OPTIKNEE consensus. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(24):1445–1453. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]