Abstract

Intracranial tumors present a significant therapeutic challenge due to their physiological location. Immunotherapy presents an attractive method for targeting these intracranial tumors due to relatively low toxicity and tumor specificity. Here we show that SCIB1, a TRP-2 and gp100 directed ImmunoBody® DNA vaccine, generates a strong TRP-2 specific immune response, as demonstrated by the high number of TRP2-specific IFNγ spots produced and the detection of a significant number of pentamer positive T cells in the spleen of vaccinated mice. Furthermore, vaccine-induced T cells were able to recognize and kill B16HHDII/DR1 cells after a short in vitro culture. Having found that glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) expresses significant levels of PD-L1 and IDO1, with PD-L1 correlating with poorer survival in patients with the mesenchymal subtype of GBM, we decided to combine SCIB1 ImmunoBody® with PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade to treat mice harboring intracranial tumors expressing TRP-2 and gp100. Time-to-death was significantly prolonged, and this correlated with increased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell infiltration in the tissue microenvironment (TME). However, in addition to PD-L1 and IDO, the GBM TME was found to contain a significant number of immunoregulatory T (Treg) cell-associated transcripts, and the presence of such cells is likely to significantly affect clinical outcome unless also tackled.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-024-03770-x.

Keywords: Brain tumor, Cancer vaccine, Glioblastoma multiforme, Immune checkpoint blockade, PD-1, TRP-2

Introduction

Intracranial tumors present a unique challenge due to their physiological location and the sensitivity of the brain as an organ. For therapy to be beneficial to patients harboring intracranial tumors, the therapy needs to penetrate the brain parenchyma and cause little to no damage to the brain itself. Many chemical therapies fail due to their inability to cross the blood brain barrier and the potential deleterious effects they have on the normal surrounding brain tissue. Immunotherapy presents an attractive therapeutic modality due to its tumor specificity and the ability of activated immune cells to cross the blood brain barrier [1]. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most frequently occurring primary brain tumor and the prognosis for patients is poor with the median survival after diagnosis being 12–15 months [2, 3]. Many other types of tumors can also metastasize into the brain. Much like primary brain tumors, brain metastases carry an equally dismal prognosis [4–6]. Both brain tumors and brain metastases are treated in a similar manner, with surgical removal of the tumor being performed (where possible) followed by radiotherapy and, in some cases, chemotherapy

SCIB1 ImmunoBody® (Scancell Limited, Nottingham, UK) is a DNA vaccine encoding a human IgG1 antibody with three epitopes from gp100 and one from TRP-2 engineered into its complementarity determining regions (CDR). There are two HLA*0201 epitopes, one from TRP-2180–188 (SVYDFFVWL) which also is H-2 Kb restricted and one from gp100178-186 (MLGTHTMEV), and two CD4 epitopes, an HLA-DR4 restricted gp10044-59 epitope (WNRQLYPEWTEAQRLD) and a gp100173–190 epitope (GTGRAMLGTHTMEVTVYH) restricted by HLA-DR7, HLA-DR53 and HLA-DQ6 [7, 8]. ImmunoBody® induces a stronger immune response than equivalent peptide vaccines, whole antigen DNA vaccines and peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (DCs) [7, 9, 10]. The IgG1 molecule encoded by SCIB1 acts as a carrier protein for the immunogenic TRP-2 and gp100 peptides, which are cross presented to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after uptake into and processing by DCs [9]. Based on promising results from pre-clinical melanoma models, a phase I/II trial of the SCIB1 ImmunoBody® in patients with melanoma demonstrated peptide-specific T cell responses in 88% of treated patients and that SCIB1 therapy was well tolerated [11]. TRP-2 and gp100 antigens represent excellent targets as their expression is not exclusive to melanoma, with expression also being seen in GBM [12–14]. This offers the possibility that the SCIB1 ImmunoBody® is effective in patients whose GBM tumors express TRP-2 and/or gp100.

The binding of programmed death protein 1 (PD-1) expressed on T cells to its cognate ligands programmed death ligands 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2) on tumors abrogates the immune response—so called ‘checkpoint inhibition’. The blockade of this interaction with monoclonal antibodies has been approved for use in many cancer types and is also being investigated as part of combinatorial therapy in numerous cancer settings. The combination of SCIB1 with PD-1 blockade has been shown to result in a strong anti-tumor effect against murine B16-F1 melanoma cells expressing human HLA-DR4 implanted subcutaneously in transgenic mice [8]. Although the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade as monotherapy for intracranial tumors has to date been limited [15–17], it presents an attractive adjunct for active immunotherapy. For example, PD-1 blockade improves responses to active immunotherapy in an orthotopic murine GBM model [18].

This study examined the immunogenicity of SCIB1 ImmunoBody® in a humanized C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 mouse model and its ability to generate T cells having the capacity to reject/delay the growth of established intracranial tumors in vivo when combined with PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

The B16HHDII/DR1 cell line was a generous gift from Scancell Ltd (Nottingham, UK). B16HHDII/DR1 cells are derived from B16-F1 murine melanoma cells that have been genetically modified so that they no longer express murine MHC. Murine MHC was knocked out using zinc-finger nuclease technology and cells were stably transfected with plasmids encoding human HHDII and DR1 molecules. These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Lonza, cat#: BE12-167F) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS (Gibco, cat#: A5670701), 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza, cat#: BE17-606E), 300 µg/mL Hygromycin B (ChemCruz, cat#: sc-29067) and 500 µg/mL Geneticin (G418) Sulfate (ChemCruz, cat#: sc-29065). B16HHDII/DR1 cells were stably transfected with the Luciferase gene and transfected cells selected for using 550 µg/mL Zeocin (InvivoGen, cat#: ant-zn-1).

Splenocytes were cultured in T cell medium – RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% v/v FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 20 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma, cat#: 83,264), 100 units/mL penicillin + 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Lonza, cat# DE17-602E) and amphotericin B (Lonza, cat#: 17-836R).

The SF-188 and SEBTA-027 human GBM cell lines were a generous gift from the University of Portsmouth Neuro-Oncology Group (Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Pilkington). SF-188 was derived from an 8-year-old male with stage IV GBM in the right frontal lobe [19]. SEBTA-027 was derived from a 59-year-old female with recurrent grade IV GBM in the right parieto-occipital region, with sarcomatous elements, wild type IDH1, MGMT is unmethylated and the original tissue was seen to have a 40% Ki67 labeling index [20]. The patient had previously received radiotherapy and Temozolomide chemotherapy. These cells were cultured in DMEM + GlutaMAX-I (Gibco, cat#: 10,566,016) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in 5% v/v CO2.

Animals and immunization schedule

C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 transgenic mice [21] were utilized for this study. These mice express the human α1 and α2 chains of HLA-A*0201 with the α3 chain of H-2Dd allele (HHDII), also expressing HLA-DRB*0101, and knocked out for the expression of murine MHC class I (H-2b) and II (I-Ab). These were provided by Dr. Lone (CNRS, Orleans, France). Animal use and care was in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU and UK Home Office Code of Practice for the housing and care of animals bred, supplied, or used for scientific purposes. The studies were undertaken with UK Home Office approval. Mice aged between 6 and 8 weeks were used for this study. SCIB1 ImmunoBody® DNA was coated onto 1.0 μm Gold Microcarriers (Bio-Rad, cat#: 1,652,263) which were subsequently administered intradermally using a Helios® gene gun (Bio-Rad). Mice were given approximately 1 µg of DNA per vaccination in the form of a priming dose on day 0 followed by a boost on day 7 and day 14, animals were terminated, and spleens removed for analysis of immune reactivity on day 21.

Ex vivo ELISpot assay

Splenocytes were obtained by flushing 10 ml of T cell medium through the spleen, the release of IFNγ from which was then determined using a murine IFNγ ELISpot kit (Mabtech, cat#: 3321-2A). For this, MultiScreenHTS IP Filter 96-well plates (Millipore, cat#: MSIPS4W10) were coated with IFNγ antibody by overnight incubation at 4 °C, after which plates were blocked by incubation with T cell medium for 30 min at room temperature. After blocking, 5 × 105 splenocytes were added to triplicate wells and incubated with peptides (1 µg/mL for class I and 10 µg/mL for class II) for approximately 40 h at 37 °C in a 5% v/v CO2 humidified incubator. Negative control wells consisted of splenocytes alone, and positive control wells consisted of splenocytes stimulated with 2.5 µg/mL of the T cell mitogen concanavalin A (Sigma, cat#: C5275). After incubation the splenocytes were removed by washing and the captured IFNγ detected using a biotinylated IFNγ antibody and an Alkaline Phosphatase Conjugate Substrate Kit (Bio-Rad, cat#: 170–6432). Spots were counted using an ImmunoSpot Analyzer (Cellular Technology Limited).

T cell isolation

Splenocytes from vaccinated mice were counted and T cells isolated using the Dynabeads™ Untouched™ Mouse T Cells Kit (Invitrogen, cat#: 11413D) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were suspended at a concentration of 1 × 108 cells/mL in isolation buffer (D-PBS (Corning, cat#: 21-031-CV) + 0.1% w/v BSA (Millipore, cat#: 12,659) + 2 mM EDTA (Sigma, cat#: E6758)). 5 × 107 cells were transferred to a fresh tube and 100 µL of heat inactivated FBS was added, 100 µL of antibody cocktail was added to the mixture and tubes were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed with 10 mL of isolation buffer by centrifugation at 350 × g for 8 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 4 mL of isolation buffer. Mouse Depletion Dynabeads™ (1 mL) were added to the cell suspension and this mix was incubated at room temperature for 15 min with gentle tilting and rotation. After incubation, 5 mL of isolation buffer was added to the mixture and the beads resuspended. This tube was then placed in a magnet for 2 min and the supernatant containing T cells was poured into a fresh tube. Cells were spun down, resuspended in T cell medium and counted.

Flow cytometry staining of TRP-2 specific T cells using a TRP-2 pentamer

Isolated T cells (1 × 106) were transferred into a 12 × 75 mm polystyrene tube and washed with 2 mL of D-PBS by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was poured off and the resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 50 µL of FBS and 0.5 µg/µL of anti-CD16/CD32 (BioLegend, cat#: 101,302, clone 93). Tubes were incubated for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were then incubated with 10 µL of Pro5 MHC pentamer (A*02:01/Kb SVYDFFVWL) APC conjugated pentamer (ProImmune) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After incubation cells were washed with 2 mL of D-PBS via centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed, and the resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 50 µL of D-PBS containing 0.3 µg FITC-conjugated mouse CD45 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Miltenyi Biotec, cat#: 130–110-658, clone REA737), 0.2 µg Brilliant Violet 421™-conjugated mouse CD3 mAb (BioLegend, cat#:100,228, clone 17A2), 0.5 µg APC/Cyanine 7conjugated mouse CD8a mAb (BioLegend, cat#:100,714, clone 53–6.7) and 0.5 µL LIVE/DEAD™ fixable yellow dead cell stain (Molecular Probes, cat#: L34959). Tubes were then incubated for 30 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cells were washed with 2 mL D-PBS via centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed, and cells resuspended in 300 mL of IsoFlow Sheath Fluid (Beckman Coulter, cat#: 8,546,859), after which they were analyzed using a Backman Coulter Gallios® flow cytometer and Kaluza® acquisition and analysis software (Beckman Coulter).

Immunocytochemical staining of B16HHDII/DR1 cells

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and stained once sufficiently confluent. Cells were first fixed in 4% w/v formaldehyde (Sigma, cat#: 252,549) in D-PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times with D-PBS, 5 min each time. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 (Sigma, cat#: X100) in D-PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed with D-PBS as before. Cells were then blocked using 2.5% v/v Normal Horse Serum (Vector Laboratories, cat#: PK-7200) for 10 min at room temperature. The serum was then removed, and cells were incubated with Avidin D solution (Vector Laboratories, cat#: SP-2001) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed in D-PBS for 2 min. Biotin (Vector Laboratories, cat#: SP-2001) was then added to cells for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with a TRP-2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:150, Abcam, cat#: ab74073) or a rabbit recombinant gp100 mAb (1:250, Abcam, cat#: ab137078, clone EP4863(2)) diluted in 2.5% v/v Normal Horse Serum overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed three times in D-PBS, cells were then incubated in Biotinylated Universal Antibody (Vector Laboratories, cat#: PK-7200) for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times in D-PBS, 5 min each time, after which they were incubated in VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Reagent (Vector Laboratories, cat#: PK-7200) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were washed in D-PBS as before and then incubated in DAB Substrate (Vector Laboratories, cat#: SK-4100) for 3 min. Cells were washed in distilled H2O for 2 min. Cells were then counterstained with Mayer’s Hematoxylin (Sigma, cat#: 51,275) and washed under tap water for 5 min. The cells on the coverslips were then mounted to slides using DPX Mountant (Sigma, cat#: 44,581) and imaged microscopically (Zeiss).

Target cell recognition and killing

At the end of the vaccination schedule, mice were euthanized and isolated splenocytes stimulated in vitro with 0.1 µg/mL of TRP-2 peptide (SVYDFFVWL) and 50 U/mL of murine IL-2 (PeproTech, cat#: 212–12) for 5 days. CD3+ T cells were then isolated using an EasySep Mouse T Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, cat#: 19,851), plated at 2.5 × 105 cells per well and co-cultured with 1 × 104 B16HHDII/DR1 cells per well (50:1 effector:target ratio) in the presence or absence of anti-mouse CD8a antibody at 20 mg/mL (Bio X Cell, cat#: BE0061, clone 2.43) in either an IFNγ ELISpot plate (for target cell recognition via the release of IFNγ) or a flat bottom 96-well plate (to assess target cell death). For target cell recognition, the murine IFNγ ELISpot assay was performed as described previously. For the assessment of target cell death, a WST-8 cytotoxicity assay was performed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Sigma, cat#: 96,992). WST-8 is bioreduced by cellular dehydrogenases to an orange formazan product that is soluble in tissue culture medium. The amount of formazan produced is directly proportional to the number of living cells. After plating the cells in a final volume of 200 µL per well, the plate was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% v/v CO2 humidified incubator. Control wells included medium alone as a blank; T cells alone and target cells alone to account for spontaneous cell death; and target cells with 0.05% w/v SDS as a death control. 20 µL of CCK-8 solution were then added to each well and incubated for 4 h in the incubator and the absorbance was read at 450 nm using an iMark Microplate Absorbance Reader (Bio-Rad).

PD-L1 and IDO1 expression in low grade glioma (LGG) and GBM

The expression of PD-L1 and IDO1 in LGG and GBM, as well as the expression of CD4, CD39, CD73, TIM3, IL-10 and TGFB1 in GBM were assessed using Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA 2, http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) [22], a web server for gene expression analysis from healthy and tumor samples obtained from the TCGA and the GTEx projects. GEPIA 2 holds data for 207 normal brain samples from the GTEx project as well as 518 LGG samples and 163 GBM samples from the TCGA project.

Intracranial tumor implantation

All animal work was carried out under a Home Office approved project license and reviewed by the Nottingham Trent University’s Animal Welfare Ethical Review Body (AWERB). The animals were housed in groups of three in Techniplast Sealsafe Plus cages and furnished with corncob bedding, chew sticks, sizzle-nest and play tunnels (Datesand Ltd., Cheshire, UK). The animals were allowed free access to food and water. A pelleted diet (Rodent 2018C Teklad Global Certified Irradiated Diet, Envigo Laboratories U.K. Ltd., Oxon, UK) was used. Mains drinking water was supplied from polycarbonate bottles attached to the cage. The diet and drinking water were considered not to contain any contaminant at a level that might have affected the purpose or integrity of the study. They were housed in a single air-conditioned room within the Bioscience Support Facilities at Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK. The rate of air exchange was at least fifteen air changes per hour and the low intensity fluorescent lighting was controlled to give twelve hours continuous light and 12 h darkness. Environmental conditions were continuously monitored by a computerized system. The temperature and relative humidity controls were set to achieve target values of 22 ± 2 °C and 55 ± 15%, respectively. Deviations from these targets were considered not to have affected the purpose or integrity of the study. The animals were allocated to treatment groups as they came to hand. These were uniquely identified within the study by an ear punching system routinely used in these laboratories.

Prior to surgery all animals had lidocaine applied on the scalp overlying the proposed craniotomy site. Buprenorphine was administered at a dose of 0.05–0.1 mg/kg s/c immediately prior to surgery and thereafter every 12 h if required. Carprofen was administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg subcutaneously immediately after surgery before recovery and thereafter every 24 h if required. Postoperatively, all animals were kept warm at 37 °C in warming box and monitored until they regained consciousness and were able to stand.

All animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane (Zoetis) at a flow rate of approximately 4 L/min. The anesthetic was maintained at 2% for the duration of the surgery. Stereotaxic intracranial implantation of B16HHDII/DR1 cells was performed by injecting 4–5 × 103 cells in 3 μL D-PBS into the striatum, avoiding the sagittal sinus vessel (2 mm lateral, right-hand side, 1 mm anterior to bregma and at a depth of 3.5 mm from the cortical surface). After 60 s the needle was withdrawn to depth of 3 mm and then cells were injected at a rate of 1.5 μL per 60 s, over 2 min. After implantation the needle was left in place for 60 s and then withdrawn at a rate of 0.1 mm every 2 s until clear of the brain. Once the injection was completed the wound was closed and mice were monitored at regular intervals.

Immunization schedule for tumor bearing mice

Mice harboring intracranial tumors were vaccinated with SCIB1 ImmunoBody® (n = 10) or sham vaccinated (n = 5) using an empty gene gun bullet on days 3, 7, 10, 17, 24 and 31 post tumor implantations. Mice were then given either 250 µg of PD-1 antibody (n = 10) (clone RMP1-14, Bio X Cell) or 250 µg of isotype control antibody (for the sham vaccinated group) (anti-Trinitrophenol clone 2A3, Bio X Cell) in a volume of 100 µL (in sterile D-PBS) intraperitoneally on days 4, 8, 11, 18, 25 and 32 post tumor implants. Mice were monitored at regular intervals twice a day, once a day at the weekend. All animals were body weighed daily and humanely culled if they displayed any of the following: Body weight loss of ≥ 18% in the first 5 days post-surgery and after 5 days post-surgery, a body weight loss of up to 15% in combination with other clinical signs, indicative of a deterioration in the physical condition of the animal or body weight loss exceeding 15% and observed in isolation. Animals were also culled if disturbances to the normal behavior repertoire such as hunched posture, subdued behavior, piloerection were observed.

Immunofluorescence

Mouse brains were harvested and fixed in 4% w/v formaldehyde at 4 °C overnight, placed in 30% w/v sucrose at 4 °C until they sunk to the bottom of the tube and then frozen-embedded in OCT compound (Scigen, cat#: 51-1625-0019); 3 brains per treatment group (n = 3) were then cryosectioned to 30 µm slices and mounted on Epredia SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, cat#: 12312148PBS); 3–4 brain slices were mounted per slide to allow for technical replicates. The slices were washed three times with D-PBS, 5 min each time. They were then washed with 0.2% v/v Triton X-100 in D-PBS for 5 min followed by a 1-h blocking step with blocking buffer composed of 5% w/v BSA diluted in 0.2% v/v Triton X-100 in D-PBS. Staining was done over a 3-day period at 4 °C using the following primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer: polyclonal guinea pig anti-mouse CD4 polyclonal antibody (1:500, Synaptic Systems, cat#: HS-360 004) and rat anti-mouse CD8a mAb (1:400, Abcam, cat#: ab22378, clone YTS169.4). Sections were washed three times with D-PBS, 5 min each time, and then incubated for 2 h with the following secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer: Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (H + L) (1:1,000, Invitrogen, cat#: A-11073) polyclonal antibody and Alexa Fluor™ 633-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (H + L) (1:1,000, Invitrogen, cat#: A-21094). Sections were washed twice with D-PBS, 5 min each time, and then washed once with 20 µg/mL of DAPI (Sigma) diluted in distilled H2O for 5 min. Sections were then mounted using VECTASHIELD Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, cat#: H-1000–10), imaged using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope and images analyzed using ImageJ [23] following the ’Automated cell counting from tissue sections’ quantification method described by Shihan and colleagues [24], replacing the auto threshold option ‘Otsu’ with ‘Yen’ for optimal thresholding.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software. The statistical test applied and the significance are indicated within the figure legends.

Results

SCIB1 ImmunoBody® generates a strong anti-TRP-2 immune response in HHDII/DR1 mice

In silico analysis using the SYFPEITHI database [25] revealed the predicted MHC binding scores of the peptides encoded by the SCIB1 vaccine (Table 1). The higher the score, the stronger the predicted binding of the peptide to the HLA allele indicated. This method was used to select the peptides used for the in vitro stimulation of splenocytes from vaccinated HHDII/DR1 humanized mice.

Table 1.

Peptides used to stimulate vaccinated splenocytes and their predicted MHC binding scores using SYFPEITHI [25]

| Peptide | Amino acid sequence | Human HLA-specificity | SYFPEITHI score |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRP-2 SVY | SVYDFFVWL | A2 (HHDII) | 21 |

| gp100 QLY | QLYPEWTEA | A2 (HHDII) | 19 |

| gp100 AML | AMLGTHTMEV | A2 (HHDII) | 26 |

| gp100 NRQ | NRQLYPEWTEAQRLD | DR1 | 14 |

| gp100 GTG | GTGRAMLGTHTMEVT | DR1 | 24 |

To determine the immunogenicity of the SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccine, C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 mice were vaccinated with the SCIB1 ImmunoBody® on day 0, 7 and 14 in a prime, boost, boost schedule and on day 21 the spleens were harvested and the splenocytes were then stimulated with the peptides identified in Table 1. The response to these peptides was measured using an IFNγ ELISpot assay. SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination generated a strong TRP-2 specific response, indicating that the TRP-2 peptide sequence within the ImmunoBody® construct was endogenously processed and presented to T cells resulting in the observed IFNγ release. Although several mice also generated responses to the gp100 peptides, these were at a much lower frequency than the TRP-2 responses observed (Fig. 1). The reduced frequency of responses to the gp100 peptides may be due to epitope dominance of the TRP-2 sequence, which is a well-known dominant sequence [26]. Moreover, due to the HLA-restriction of the mice used here, it is entirely possible that the full T cell helper repertoire which could be generated via other MHC class-II gp100 derived peptides was not generated compared to what can be achieved with the same vaccine administered in humans [11].

Fig. 1.

ELISpot results from in vitro stimulated splenocytes from SCIB1 ImmunoBody.® vaccinated C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 mice. **** p ≤ 0.0001 as determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (n = 16–31)

To further examine the presence of TRP-2 specific CD8+ T cells, TRP-2 pentamer staining was performed on CD3+ cells isolated from SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccinated and naïve mice. Pentamer staining revealed a significant increase in the percentage of TRP-2 specific CD8+ T cells in the spleens of SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccinated mice when compared to unvaccinated naïve mice (Fig. 2). These data demonstrate that vaccination increases the percentage of CD8+ T cells specific for the TRP-2 180–188 amino acid sequence, further supporting the IFNγ ELISpot results reported.

Fig. 2.

TRP-2 pentamer positive cells in CD3+ cells isolated from SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccinated mice. A Example of the gating strategy used to analyze the TRP-2 pentamer staining with example plots from, B naïve splenocytes and C SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccinated splenocytes. D Percentage of pentamer positive CD45+, CD3+, CD8+ splenocytes from naïve and SCIB1 ImmunoBody.® vaccinated mice. * p ≤ 0.05 as determined by an unpaired t test (n = 6)

We have shown that SCIB1 ImmunoBody® generates a strong immune response which resulted in the recognition of the TRP-2180–188 sequence, a sequence which has previously been shown to be vital for the rejection of murine melanoma [26]. B16 cells are well-known to express both TRP-2 [26, 27] and gp100 [28, 29], and our own analyses revealed that B16HHDII/DR1 cells also express TRP-2 and gp100 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Immunocytochemical staining of the B16HHDII/DR1 cell line. A TRP-2 staining, B gp100 staining, C No primary antibody control. Positive staining is indicated by brown coloration. Scale bar = 150 µm

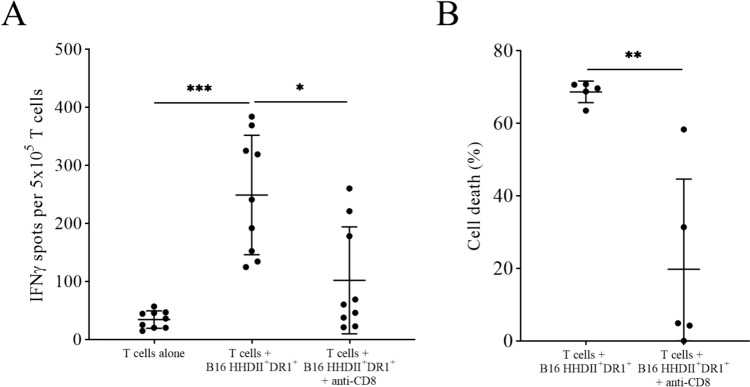

B16HHDII/DR1 cells were then used as target cells in a co-culture assay with T cells isolated from the splenocytes from immunized mice that had been cultured in vitro with TRP-2180–188 peptide and IL-2. The results showed that the T cells from vaccinated mice recognize B16HHDII/DR1 cells in a CD8-specific manner (Fig. 4A) by releasing IFNγ and trigger their cytotoxicity, as assessed by a WST-8 cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Vaccine-induced T cell-specific B16HHDII/DR1 recognition and killing after short-term in vitro culture with TRP-2 peptide and IL-2. Splenocytes of immunized animals were cultured for 7 days in vitro in the presence of low levels of TRP-2 and IL-2. Seven days later, CD3+ T cells were isolated and co-cultured with B16.HHDII/DR1 cells at an E:T ratio of 50:1 in the presence or absence of anti-mouse CD8a antibody in either an IFNγ ELISpot plate to assess target recognition (A) or in a flat bottom 96-well plate to assess target killing using a WST-8 cytotoxicity assay (B). For the IFNγ ELISpot, * p ≤ 0.05 and *** p ≤ 0.001 as determined by a Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (n = 9). For the WST-8 cytotoxicity assay, ** p ≤ 0.01 as determined by a paired t test (n = 5)

Although checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment for some cancers such as melanoma, not all types of cancer respond due to their lack of PD-L1 expression, Furthermore, some cancers face additional hurdles due to the immunosuppressive effect of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression. We therefore assessed whether GBM would lend itself for such a therapy in combination with active immunotherapy.

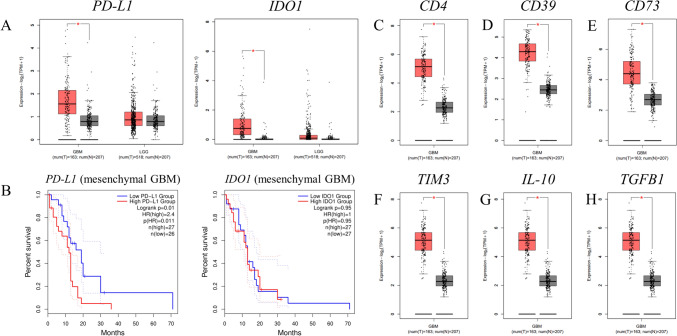

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis database (GEPIA2, http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn) revealed a significantly higher expression of PD-L1 and IDO1 transcripts in GBM patient samples compared to normal tissue, and in both cases the difference in expression was marked when compared to low grade glioma (LGG) (Fig. 5A). Patients with high expression of PD-L1 also have a significantly lower overall survival than those with a low expression of the molecule (albeit only for the mesenchymal subtype of GBM) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

GEPIA2 gene analysis of immunosuppressive gene expression in low grade glioma (LGG) and GBM. A PD-L1 and IDO1 expression is shown in healthy samples compared with LGG and GBM samples; * p ≤ 0.01 as determined by one-way ANOVA and log2FC cutoff value of 0.7. B Kaplan Meier survival curves are also shown for both genes; p = 0.011 and p = 0.95 as determined by a Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. C CD4, D CD39, E CD73, F TIM3, G IL-10 and H TGFB1 expression is shown in healthy samples compared to GBM samples; * p ≤ 0.01 as determined by one-way ANOVA and log2FC cutoff value of 1

On the basis of these findings, we combined SCIB1 ImmunoBody® with PD-1 checkpoint inhibition.

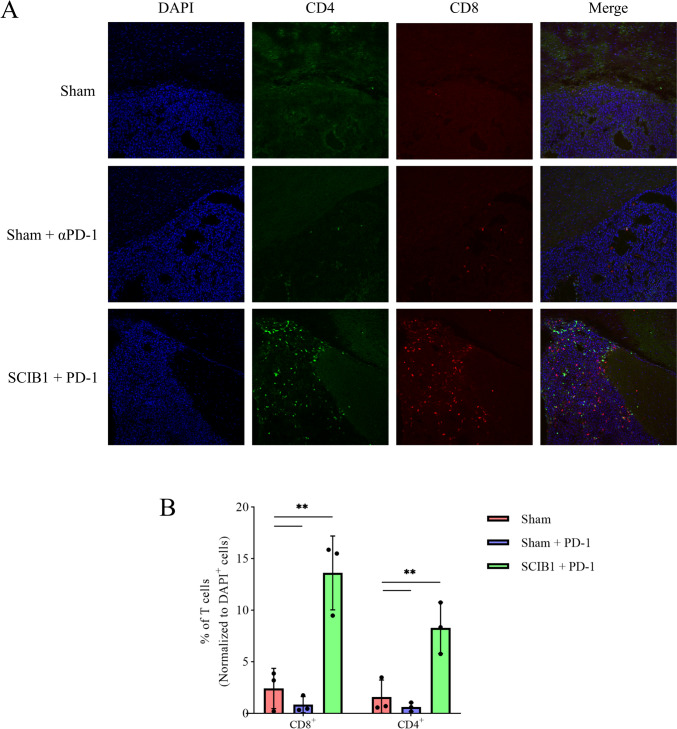

SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination in combination with PD-1 blockade prolongs the time-to-death of mice bearing intracranial B16HHDII/DR1 tumors and promotes T cell tumor infiltration

B16HHDII/DR1 cells were injected into the brains of C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 mice. These mice were then vaccinated with SCIB1 ImmunoBody® or sham vaccinated on days 3, 7,10, 17, 24 and 31 post tumor implantation. Mice were also given 250 µg PD-1 mAb or isotype control antibody on days 4, 8, 11, 18, 25 and 32 post tumor implantation. Mice bearing intracranial B16HHDII/DR1 cells showed prolonged survival when receiving combined SCIB1 and anti-PD-1 therapy after tumor implantation (Fig. 6). PD-1 mAb treatment had a modest time-to-death benefit when administrated alone compared to sham vaccinated mice that received an isotype control antibody. These data suggest that the effect of PD-1 blockade on survival was modest; whereas, the addition of SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination to PD-1 blockade resulted in a significantly improved time-to-death gap of mice harboring intracranial tumors. This correlated with a significantly higher number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the tumor micro-environment in the combined therapy compared to both sham and sham + anti-PD-1 treatment groups (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

A Schematic representation of the therapeutic dosing regimen utilized to treat intracranial B16HHDII/DR1 tumors. B Kaplan Meier survival curve of mice bearing intracranial B16.HHDII/DR1 Luc tumors. ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001 as determined by a Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (n = 5 for sham vaccinated mice; n = 10 for sham + PD-1 as well as SCIB1 + PD-1 treatment groups)

Fig. 7.

Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration following SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination. The cryosectioned brains of sham, sham + anti-PD-1 and SCIB1 ImmunoBody® + anti-PD-1 vaccinated mice were stained for CD4 and CD8a and imaged to study T cell tumor infiltration (A); the acquired images were processed using ImageJ to quantify CD4+ and CD8.+ T cells within the tumor area (B). ** p ≤ 0.01 as determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (n = 3)

These proof-of-concept experiments revealed that combining SCIB1 ImmunoBody® and PD-1 blockade represents an attractive therapeutic option for intracranial tumors expressing TRP-2 and, to a lesser extent, gp100.

Discussion

Intracranial tumors present a unique therapeutic challenge due to their physiological location; and while, the brain was previously thought to be an immunoprivileged site, there is increasing evidence which suggests that this is not the case and active immune responses have now been reported [30–32]. Primary brain tumors, especially GBM tumors, have previously been shown to express both the TRP-2 and gp100 melanoma antigens due to the shared neuroectodermal origin of both tissue types [12–14]. Although expression is not ubiquitous, a large proportion of tumors express at least one of these antigens, making them attractive targets for the immunotherapeutic treatment of GBM. Our analyses of GBM tissue microarrays (TMAs) revealed that 22/33 (66%) of cases studied express the TRP-2 antigen as indicated by IHC (Supplementary Fig. 1). The expression level varied among the cases studied, with 1/33 (3%) having strong staining, 4/33 (12%) having moderate staining and 17/33 (52%) having low levels of staining. GBM tissues were also stained with an antibody directed against gp100, however only weak staining was observed in 1/33 (3%) of cases and the other 32 cases were negative (data not shown). Other research has found that a high proportion of GBM cell lines and tissues express gp100 [13, 14]; however, the samples included in our tissue microarray did not appear to have the same level of gp100 expression.

The work presented here made use of C57BL/6 mice which have been engineered to express no murine MHC molecules but instead express chimeric HLA-A2 and human HLA-DR1 molecules [21]. Using these mice, we were able to show that SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination generated a strong TRP-2 specific immune response in vaccinated mice. SCIB1 ImmunoBody® has already been shown to generate stronger, and more potent immune responses than other vaccine methods such as peptides or peptide-pulsed DCs [7].

Here we show that this method of vaccination resulted in a high frequency of TRP-2 specific CD8+ T cells. More importantly, we showed that vaccine-induced T cells isolated after a short in vitro culture could recognize and kill B16HHDII/DR1 cells in a CD8+ dependent manner. Since GBM tumors express high levels of PD-L1, which was shown to be linked to shorter survival, we decided to combine SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination with PD-1 blockade to assess the time-to-death of humanized C57BL/6 HHDII/DR1 mice harboring intracranial B16HHDII/DR1 tumors expressing TRP-2 and gp100. While this model is far from ideal due to the use of heavily modified tumor cells inserted directly in the brain of the mice, it allows us to investigate whether a vaccine such as SCIB1, which has already demonstrated great clinical benefit in malignant melanoma patients [11] delivered systemically, could produce a clinically relevant outcome for a tumor located in the brain. We have been able to demonstrate that immune cells activated using the SCIB1 ImmunoBody® vaccination can exert therapeutic efficacy in an intracranial tumor model prolonging the time-to-death of mice when combined with anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade. This intracranial B16HDDII/DR1 tumor model acts as a proof-of-concept for targeting intracranial tumors expressing TRP-2 and gp100.

Importantly, the ImmunoBody® construct can also be engineered so that other antigens can be targeted, with constructs encoding the Wilms tumor 1 (WT1) and HAGE antigens showing efficacy in vivo [33, 34]. A combinatorial WT1 and HAGE ImmunoBody® vaccine demonstrated efficacy against tumors expressing HAGE and WT1 antigens [34]. In addition, it has also been shown that these antigens are expressed by GBM tumors and cell lines [35–37].

The targeting of multiple antigens will help to overcome the development of immune escape variants, enabling long-term tumor eradication. However, a successful vaccine will induce the production of IFNγ, and this cytokine is able to actively upregulate expression of PD-L1 on the surface of many cells, including the GBM cell lines we tested (Supplementary Fig. 2), making the blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway an attractive adjunct for SCIB1 ImmunoBody® immunotherapy. Furthermore, other analyses have revealed that PD-L1 expression is observed in GBM tumor tissues, and this expression is linked with poorer patient survival [38, 39]. Importantly, PD-L1 is not the only immunosuppressive protein upregulated in response to IFNγ. Infiltrating T cells have been shown to increase IDO expression in GBM and contribute to a decreased patient survival [40]; we have also found that both SEBTA-027 and SF-188 cell lines upregulated immunosuppressive IDO in response to IFNγ (Supplementary Fig. 3) and we are currently investigating this in our model. This in turn was shown to increase the recruitment of immunoregulatory T (Treg) cells and decrease overall survival in experimental mice with brain tumors [41]. Furthermore, we have found that the TME of GBM patients has significantly higher levels of CD4, CD39, CD73, TIM3, IL-10 and TGFB1 transcripts, pointing toward high levels of Treg cells (Fig. 5C–H). It would therefore be of particular interest to test the possibility of reprogramming these Treg cells into effector T cells with the combined use of αGITR and αPD-1 antibodies [42].

In summary, we propose that active immunotherapy in the form of SCIB1 ImmunoBody® therapy should next be assessed with both αGITR and αPD-1 antibodies or with additional means to relieve T cell exhaustion, as this could lead to an enhanced survival outcome.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Andrew Marr, Joseph Lenton, Gareth Williams and Graham Hickman for their technical support.

Author contributions

JRDP and SEBM contributed to conceptualization; JRDP, CPS and JET contributed to data curation; JRDP, CPS and JET contributed to formal analysis; SEBM and AGP contributed to funding acquisition; JRDP, CPS, JET, LDH, MA, LCW, AMM and SEBM contributed to investigation; JRDP, LDH, LW, AM and CJT contributed to methodology; SEBM contributed to project administration; LDH, VAB and LD contributed to resources; SEBM and AGP contributed to supervision; JRDP and CPS contributed to visualization; JRDP, AGP and SEBM contributed to writing—original draft; JRDP, CPS, VAB and LD contributed to writing—review and editing: All authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Headcase Cancer Trust (UK), the John and Lucille van Geest Foundation, Nottingham Trent University QR allocation and the John van Geest Cancer Research Centre (Nottingham Trent University). Scancell Ltd also generously provided materials used in this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Author LD is a director and shareholder of Scancell Ltd and is a named inventor of the ImmunoBody® patents; she declares no non-financial competing interests. All other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pearson JRD, Cuzzubbo S, McArthur S et al (2020) Immune escape in glioblastoma multiforme and the adaptation of immunotherapies for treatment. Front Immunol 11:582106. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.582106 10.3389/fimmu.2020.582106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352:987–996. 10.1056/NEJMoa043330 10.1056/NEJMoa043330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen PY, Kesari S (2008) Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med 359:492–507. 10.1056/NEJMra0708126 10.1056/NEJMra0708126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB (2005) Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol 75:5–14. 10.1007/s11060-004-8093-6 10.1007/s11060-004-8093-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim T, Song C, Han JH et al (2018) Epidemiology of intracranial metastases in Korea: a national cohort investigation. Cancer Res Treat 50:164–174. 10.4143/crt.2017.072 10.4143/crt.2017.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavouridis VK, Harary M, Hulsbergen AFC et al (2019) Survival and prognostic factors in surgically treated brain metastases. J Neurooncol 143:359–367. 10.1007/s11060-019-03171-6 10.1007/s11060-019-03171-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metheringham R, Pudney V, Gunn B et al (2009) Antibodies designed as effective cancer vaccines. MAbs 1:71–85 10.4161/mabs.1.1.7492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue W, Brentville VA, Symonds P et al (2016) SCIB1, a huIgG1 antibody DNA vaccination, combined with PD-1 blockade induced efficient therapy of poorly immunogenic tumors. Oncotarget 7:83088–83100. 10.18632/oncotarget.13070 10.18632/oncotarget.13070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pudney VA, Metheringham RL, Gunn B et al (2010) DNA vaccination with T-cell epitopes encoded within Ab molecules induces high-avidity anti-tumor CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol 40:899–910. 10.1002/eji.200939857 10.1002/eji.200939857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brentville VA, Metheringham RL, Gunn B, Durrant LG (2012) High avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be selected into the memory pool but they are exquisitely sensitive to functional impairment. PLoS ONE 7:e41112. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041112 10.1371/journal.pone.0041112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel PM, Ottensmeier CH, Mulatero C et al (2018) Targeting gp100 and TRP-2 with a DNA vaccine: incorporating T cell epitopes with a human IgG1 antibody induces potent T cell responses that are associated with favourable clinical outcome in a phase I/II trial. Oncoimmunology 7:e1433516. 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1433516 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1433516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu G, Khong HT, Wheeler CJ et al (2003) Molecular and functional analysis of tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-2 as a cytotoxic T lymphocyte target in patients with malignant glioma. J Immunother 26:301–312. 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00002 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu G, Ying H, Zeng G et al (2004) HER-2, gp100, and MAGE-1 are expressed in human glioblastoma and recognized by cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res 64:4980–4986. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3504 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saikali S, Avril T, Collet B et al (2007) Expression of nine tumour antigens in a series of human glioblastoma multiforme: interest of EGFRvIII, IL-13Ralpha2, gp100 and TRP-2 for immunotherapy. J Neurooncol 81:139–148. 10.1007/s11060-006-9220-3 10.1007/s11060-006-9220-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taggart D, Andreou T, Scott K et al (2018) Anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 efficacy in melanoma brain metastases depends on extracranial disease and augmentation of CD8+ T cell trafficking. Proc Natl Academy Sci U S A 115:E1540–E1549. 10.1073/pnas.1714089115 10.1073/pnas.1714089115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eguren-Santamaria I, Sanmamed MF, Goldberg SB et al (2020) PD-1/PD-L1 blockers in NSCLC brain metastases: challenging paradigms and clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res 26:4186–4197. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0798 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khasraw M, Reardon D, Weller M, Sampson J (2020) PD-1 Inhibitors: Do they have a future in the treatment of glioblastoma? Clin Cancer Res An Off J Am Associ Cancer Res 26:5287–5296. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1135 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonios JP, Soto H, Everson RG et al (2016) PD-1 blockade enhances the vaccination-induced immune response in glioma. JCI Insight 1:e87059. 10.1172/jci.insight.87059 10.1172/jci.insight.87059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutka JT, Giblin JR, Dougherty DY et al (1987) Establishment and characterization of five cell lines derived from human malignant gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 75:92–103. 10.1007/BF00686798 10.1007/BF00686798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stangl S, Foulds GA, Fellinger H et al (2018) Immunohistochemical and flow cytometric analysis of intracellular and membrane-bound Hsp70, as a putative biomarker of glioblastoma multiforme, using the cmHsp70.1 monoclonal antibody. In: Calderwood SK, Prince TL (eds) Chaperones: methods and protocols. Springer, New York, pp 307–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pajot A, Michel M-L, Fazilleau N et al (2004) A mouse model of human adaptive immune functions: HLA-A2.1-/HLA-DR1-transgenic H-2 class I-/class II-knockout mice. Eur J Immunol 34:3060–3069. 10.1002/eji.200425463 10.1002/eji.200425463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C et al (2019) GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 47:W556–W560. 10.1093/nar/gkz430 10.1093/nar/gkz430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW (2012) NIH image to imageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9:671–675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shihan MH, Novo SG, Le Marchand SJ et al (2021) A simple method for quantitating confocal fluorescent images. Biochem Biophys Rep 25:100916. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.100916 10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.100916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP et al (1999) SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics 50:213–219. 10.1007/s002510050595 10.1007/s002510050595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins PF et al (1997) Identification of Tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med 185:453–460 10.1084/jem.185.3.453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellone M, Cantarella D, Castiglioni P et al (2000) Relevance of the tumor antigen in the validation of three vaccination strategies for melanoma. J Immunol 165:2651–2656. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2651 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhai Y, Yang JC, Spiess P et al (1997) Cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the murine homologues of the human melanoma antigens MART1 and gp100. J Immunother 20:15–25. 10.1097/00002371-199701000-00002 10.1097/00002371-199701000-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peter I, Mezzacasa A, LeDonne P et al (2001) Comparative analysis of immunocritical melanoma markers in the mouse melanoma cell lines B16, K1735 and S91–M3. Melanoma Res 11:21–30. 10.1097/00008390-200102000-00003 10.1097/00008390-200102000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sokratous G, Polyzoidis S, Ashkan K (2017) Immune infiltration of tumor microenvironment following immunotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme. Hum Vaccin Immunother 13:2575–2582. 10.1080/21645515.2017.1303582 10.1080/21645515.2017.1303582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ratnam NM, Gilbert MR, Giles AJ (2019) Immunotherapy in CNS cancers: the role of immune cell trafficking. Neuro Oncol 21:37–46. 10.1093/neuonc/noy084 10.1093/neuonc/noy084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandrone S, Moreno-Zambrano D, Kipnis J, van Gijn J (2019) A (delayed) history of the brain lymphatic system. Nat Med 25:538–540. 10.1038/s41591-019-0417-3 10.1038/s41591-019-0417-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almshayakhchi R, Nagarajan D, Vadakekolathu J et al (2021) A Novel HAGE/WT1-immunobody® vaccine combination enhances anti-tumour responses when compared to either vaccine alone. Front Oncol 11:636977. 10.3389/fonc.2021.636977 10.3389/fonc.2021.636977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagarajan D, Pearson J, Brentville V et al (2021) Helicase antigen (HAGE)-derived vaccines induce immunity to HAGE and ImmunoBody®-HAGE DNA vaccine delays the growth and metastasis of HAGE-expressing tumors in vivo. Immunol Cell Biol 99:972–989. 10.1111/imcb.12485 10.1111/imcb.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennis SL, Manji SSM, Carrington DP et al (2002) Expression and mutation analysis of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene in human neural tumors. Int J Cancer 97:713–715. 10.1002/ijc.10106 10.1002/ijc.10106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark AJ, Dos Santos WG, McCready J et al (2007) Wilms tumor 1 expression in malignant gliomas and correlation of +KTS isoforms with p53 status. J Neurosurg 107:586–592. 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0586 10.3171/JNS-07/09/0586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama Y, Komiyama M, Miyata H et al (2014) Novel cancer-testis antigen expression on glioma cell lines derived from high-grade glioma patients. Oncol Rep 31:1683–1690. 10.3892/or.2014.3049 10.3892/or.2014.3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nduom EK, Wei J, Yaghi NK et al (2016) PD-L1 expression and prognostic impact in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 18:195–205. 10.1093/neuonc/nov172 10.1093/neuonc/nov172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han J, Hong Y, Lee YS (2017) PD-L1 expression and combined Status of PD-L1/PD-1–positive tumor infiltrating mononuclear cell density predict prognosis in glioblastoma patients. J Pathol Transl Med 51:40–48. 10.4132/jptm.2016.08.31 10.4132/jptm.2016.08.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhai L, Ladomersky E, Lauing KL et al (2017) Infiltrating T cells increase IDO1 expression in glioblastoma and contribute to decreased Patient survival. Clin Cancer Res 23:6650–6660. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0120 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wainwright DA, Balyasnikova IV, Chang AL et al (2012) IDO expression in brain tumors increases the recruitment of regulatory T cells and negatively impacts survival. Clin Cancer Res 18:6110–6121. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2130 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amoozgar Z, Kloepper J, Ren J et al (2021) Targeting Treg cells with GITR activation alleviates resistance to immunotherapy in murine glioblastomas. Nat Commun 12:2582. 10.1038/s41467-021-22885-8 10.1038/s41467-021-22885-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].