Abstract

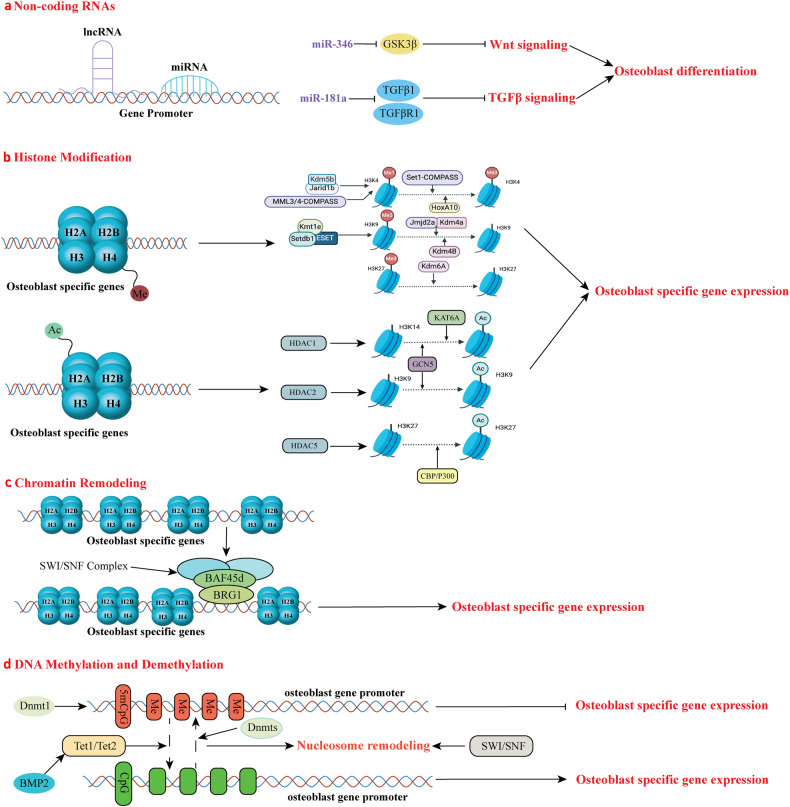

The initiation of osteogenesis primarily occurs as mesenchymal stem cells undergo differentiation into osteoblasts. This differentiation process plays a crucial role in bone formation and homeostasis and is regulated by two intricate processes: cell signal transduction and transcriptional gene expression. Various essential cell signaling pathways, including Wnt, BMP, TGF-β, Hedgehog, PTH, FGF, Ephrin, Notch, Hippo, and Piezo1/2, play a critical role in facilitating osteoblast differentiation, bone formation, and bone homeostasis. Key transcriptional factors in this differentiation process include Runx2, Cbfβ, Runx1, Osterix, ATF4, SATB2, and TAZ/YAP. Furthermore, a diverse array of epigenetic factors also plays critical roles in osteoblast differentiation, bone formation, and homeostasis at the transcriptional level. This review provides an overview of the latest developments and current comprehension concerning the pathways of cell signaling, regulation of hormones, and transcriptional regulation of genes involved in the commitment and differentiation of osteoblast lineage, as well as in bone formation and maintenance of homeostasis. The paper also reviews epigenetic regulation of osteoblast differentiation via mechanisms, such as histone and DNA modifications. Additionally, we summarize the latest developments in osteoblast biology spurred by recent advancements in various modern technologies and bioinformatics. By synthesizing these insights into a comprehensive understanding of osteoblast differentiation, this review provides further clarification of the mechanisms underlying osteoblast lineage commitment, differentiation, and bone formation, and highlights potential new therapeutic applications for the treatment of bone diseases.

Subject terms: Developmental biology, Cell signalling, Mechanisms of disease

Introduction

Adult bone comprises three main cell types: osteoblasts, osteocytes (both of which are derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)), and osteoclasts (which are derived from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)). Regarding bone homeostasis, osteoblasts function to form bone tissue, osteoclasts resorb and degrade bone tissue, while the primary role of osteocytes is to maintain the structural integrity and function of bone by controlling the activity of both osteoclasts and osteoblasts. These opposing cell types regulate the physiological bone turnover rate, which can be separated into two stages: modeling and remodeling. Bone modeling happens continuously during development, while remodeling is involved in tissue renewal over the course of a person’s life. Bone remodeling typically initiates with osteoclasts breaking down the matrix, consisting mainly of type I collagen and crystalline hydroxyapatite proteins. Once resorption occurs, osteoblasts are recruited to the area to produce and mineralize fresh matrix. In the bone matrix, osteoblasts create a critical assortment of macromolecules, including collagen and non-collagen proteins, which act as a platform for lattice mineralization by means of hydroxyapatite formation. Imbalances in the quantity and ratio of osteoblasts to osteoclasts, stemming from bone tissue remodeling, can give rise to conditions such as osteoporosis and other phenotypically akin disorders. As such, there has been continued research on osteoblast differentiation to elucidate mechanisms with therapeutic potential. This review examines the recent advancements in the understanding of cell signaling, transcription, epigenetics, extracellular interplay, and physiological mechanisms that underpin osteoblast differentiation and their application to the treatment of related diseases.

Osteoblast function

Osteoblasts, a major cellular component of bone and the terminal differentiation products of MSCs, have three main functions. First, osteoblasts play a pivotal role as the primary cellular regulator of bone formation. This involves synthesizing and releasing various proteins found in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of bone, along with orchestrating gene expression to facilitate ECM mineralization. With the assistance of β1 integrin, osteoblasts interface with the current matrix to shape cadherin-connected monolayers. Whenever osteoblasts are activated, they secrete a matrix consisting primarily of collagen type I and other vital components (Table 1), as well as significant developmental factors, such as bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)1. Previous research also indicates that osteoblasts play important roles in glucose homeostasis via insulin signaling because it increases osteocalcin activity2.

Table 1.

Osteoblast dysfunction-associated genes and their mouse models.

| Gene | Role of gene/protein | Defective phenotype caused by mutation | Diseases caused by mutation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP1 | A transcriptional factor that can regulate osteoblast-specific genes, such as ALP, collagen type I, or OPN. | Osteopetrosis. | Embryonic lethality, persistent truncus arteriosus, congenital chronic diarrhea | 433,434 |

| ATF4 | Determines the initiation and terminal differentiation of osteoblasts. | Osteoblast differentiation delay. | Coffin-Lowry Syndrome | 354 |

| β-catenin | Essential for preventing osteoblast transdifferentiation into chondrocytes or adipocytes and for osteoblast differentiation. | Inhibits osteoblast differentiation and instead develops into chondrocytes. | Cancer; Aggressive fibromatosis; Pulmonary fibrosis; Cleft palate; hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome (HPT-JT) | 65,66,435–438 |

| C/EBPβ and –δ | A vital transcription factor. Runx2 can regulate C/EBP expression, and C/EBP induces the expression of OCN by direct binding within its promoter. It is necessary for osteoblast mineralization. | Deferred bone arrangement, obstructed osteoblast mineralization, and vital gene expression. | N/A | 439–445 |

| CBFβ | Through its interaction with transcriptional factors like Runxs and ATF4, it is an important factor in the formation of the skeleton. | Impairs osteoblast differentiation. | Skeletal deformities, CCD | 379–381 |

| DLX3 | Positively and negatively regulates osteoprogenitor cell differentiation and gene transcription. | Inhibits induction of osteogenic markers. | Osteoporosis, Tricho-Dento-Osseous syndrome (TDO) | 446–449 |

| DLX5 | Hinders adipocyte arrangement and manages the expression of transcription factors that control osteoblast differentiation. | Extreme craniofacial, pivotal, and affixed skeletal irregularities. | Split-hand/split-foot malformation (SHFM) | 450–454 |

| ETS1 | Regulates OPN and ALP expression by cooperating with Runx2. | Runx2 and OPN were among the key genes whose expression was reduced, as was osteoblast differentiation. | N/A | 455–457 |

| HES1 | A downstream effector of the Notch signaling pathway. Binds to Cbfα1 and potentiates its transactivating capability. | Defective functions of mammalian Runt-related proteins. | Severe neurulation defects | 458,459 |

| HEY1 | A negative regulator of osteoblast differentiation and maturation. | Enhanced osteoblast matrix mineralization. | Potentially related to cardiac hypertrophy | 460–462 |

| LEF1 | Regulates osteoblast differentiation by Wnt3a and BMP2 through binding with Runx2. | Affects osteoblast differentiation. | Human sebaceous adenoma, human sebaceoma | 375,463 |

| MENIN | Regulates osteoblast generation and differentiation, which are aided and sustained by TGF-β and BMP2. | Reduced ALP activation and OCN and Runx2 expression. | Human MEN1 disease, ossifying fibroma (OF), osteoporosis | 464–468 |

| MSX2 | Inhibits adipocyte formation and stimulates mesenchymal cells to differentiate into osteoblasts. | Premature fusion of calvarial sutures. | Boston-type craniosynostosis | 469–471 |

| Osterix | Contributes to the final phase of osteogenesis and maturation, regulating the development of functional osteoblasts and their subsequent differentiation. | Devoid of osteoblasts. | Osteosarcoma; bone metastasis of cancers; Juvenile Paget’s disease (JPD) | 472 |

| PPAR-γ | Regulator of adipocyte differentiation and inhibits Runx2-mediated OCN transcription and osteoblast late differentiation. | High bone mass with increased osteoblastogenesis. | Partial lipodystrophy, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome | 473–475 |

| RUNX2 | Serves as the main switch for triggering the differentiation of osteoblasts and negatively regulates bone formation at the end of differentiation. | There are no osteoblasts, and the final stage of chondrocyte differentiation is blocked. | Delayed tooth eruption, cleidocranial dysplasia | 289,290 |

| RUNX1 | A key regulator of osteoblast and chondrocyte homeostasis, it positively regulates osteoblast differentiation and inhibits adipocyte formation. | Reduced osteoblast number and cartilage were absent. | Osteoporosis | 311,315,317 |

| RUNX3 | Participates in intramembranous and endochondral bone ossification during skeleton development. | The number of osteoblasts and mineral deposition capacity decreased. | Congenital osteopenia | 324,476 |

| SALL4 | Promotes osteoblast differentiation by suppressing Notch2-targeted gene expression and nuclear translocation. | Osteoblast differentiation is inhibited. | Holt-Oram syndrome (HOS) | 238,477 |

| SMAD | Regulates targeted gene expression via interacting with Runx2, AP-1, and SP-1. | A phenotype similar to that of CCD. | CCD | 478 |

| SMAD3 | Inhibits osteoblast differentiation and reduces osteocalcin and Cbfa1 expression. | Osteoblast differentiation rates declined. | Metastatic colon cancer | 114,479 |

| STAT1 | Binding to Runx2 inhibits nuclear translocation of Runx2 and reduces Runx2 activity. | Excessive osteoblast differentiation and increased bone mass. | Be involved in human achondroplasia | 480–482 |

| SATB2 | A molecular node controls osteoblast differentiation in the transcriptional network. | Osteoblast differentiation is lacking. | Cleft palate; SATB2-associated syndrome (SAS, Glass syndrome) | 483 |

| TAZ/YAP | Encourages the periosteal osteoblast precursors’ expansion and differentiation and acts with R-Smads to stimulate osteoblast-specific gene expression. | The number of differentiated osteoblasts decreased. | Skeletal fragility, long bone fractures | 484–487 |

Second, osteoclast differentiation can be directly regulated by osteoblast protein expression3. For example, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa β ligand (RANKL), two fundamental proteins for osteoclast differentiation, can be expressed by osteoblasts (Fig. 1)4. Osteoblast-produced M-CSF and RANKL have the ability to bind to C-FMS and RANK receptors (respectively) on osteoclast progenitors, triggering subsequent signals that promote osteoclast differentiation by activating the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFATc1)5. Osteoblasts secrete osteoprotegerin (OPG) and can regulate osteoclasts by binding to RANKL, preventing RANKL from binding to RANK. Chemoattractants (CCL8, CCL6, and CCL12) that can influence osteoclast differentiation and recruit osteoclast precursors to bone are also regulated by osteoblast calcineurin/NFAT signaling6. Osteoclasts can also regulate osteoblast differentiation. Previous work in our had found that osteoclasts regulate osteoblast differentiation and tooth root formation via IGF/AKT/mTOR signaling7 (Fig. 2).

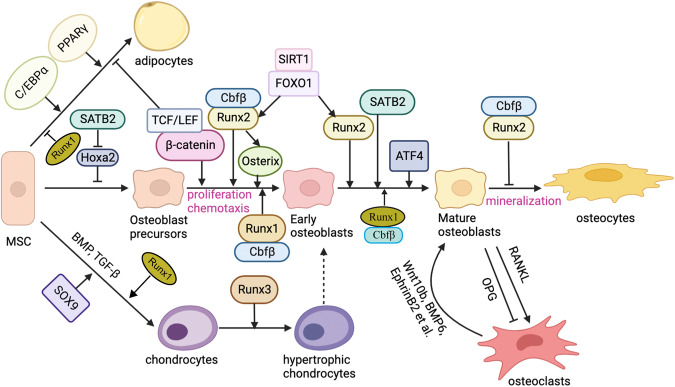

Fig. 1. Different transcription factors regulate three different differentiation fates — adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes from MSCs.

MSCs have three different differentiation fates — adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes — which are regulated by different genes. In the differentiation process, some cells in the three differentiation pathways also have a reciprocal transformation relationship through the regulation of related genes, such as interactions between mature osteoblasts and mature osteoclasts or hypertrophic chondrocytes and early osteoblasts. Transcription factors have different functions in different stages of osteoblast differentiation. Runx2 is a vital factor in all osteoblast differentiation stages; Runx2 promotes osteoblast differentiation in the early stage while inhibiting mature osteoblast differentiation into osteocytes. Cbfβ is the major co-factor of Runx2 and Runx1. Runx3 can promote chondrocytes into hypertrophic chondrocytes. SIRT1 and FOXO1 can promote Runx2 expression. Osx and β-catenin also have important functions in the early stage of osteoblast differentiation. SATB2 and ATF4 are important in promoting the terminal differentiation stage of osteoblast. SATB2 inhibits Hoxa2 activity in the early stage of osteoblast differentiation. Runx1 plays an important role in inhibiting adipocyte differentiation and promoting chondrocyte differentiation. The interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts is also very important. Osteoblasts regulate osteoclast differentiation via RANKL signaling and inhibit osteoclast differentiation through OPG. Similarly, osteoclasts can regulate osteoblast differentiation through the Wnt10b, BMP6, or Ephrin signaling pathway.

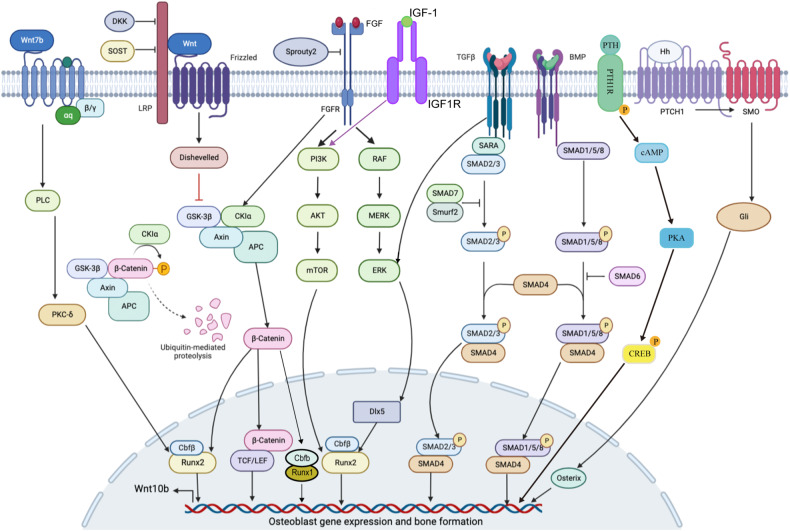

Fig. 2. Canonical signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation.

Several canonical signaling pathways control the activity of key transcription factors to mediate osteoblast differentiation. Wnt, TGF-β, BMP, FGF, and Hedgehog pathways are the most classic pathways that have been studied during osteoblast differentiation. Wnt binds with FZD receptors, causing the β-catenin accumulation. β-catenin then moves to the nucleus, in which it causes target genes to be transcribed. Wnt signaling also regulates Runx1 and Runx2 functions. TGF-β and BMP signaling regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression through multiple Smad proteins. TGF-β signaling mainly activates Smad2/3, while BMP signaling activates Smad1/5/8. FGF and FGFR can also regulate osteoblast differentiation and osteoblast-specific gene expression via downstream pathways such as PI3K-AKT and ERK pathways. Runx2, Osterix, and several other transcription factors are also necessary for osteoblast differentiation, and these transcription factors are regulated by these classic pathways. Hedgehog signaling is activated through Hh ligand binding to the 12-transmembrane receptor Patched 1 (PTCH1), which relieves inhibition of the seven-pass transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor Smoothened (SMO). Actived SMO can initiate the intracellular cascade leading to the activation of three Gli transcription factors, and Gli can then translocate into the nucleus and regulate Osx activation, thereby modulating osteoblast-specific gene expression. PTH regulates osteoblast differentiation by binding with PTH1R, subsequently activating cAMP and PKA, leading to the phosphorylation of CREB to regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression. IGF-1 binds to its receptor IGF1R and activates PI3K-Akt pathway, resulting in the activation of mTOR and promotion of osteoblast differentiation.

Third, osteoblasts are inextricably linked to the behavior and function of HSCs8. Research has demonstrated the significant involvement of osteoblasts in the HSC microenvironment9–11. Based on studies of PTH/parathyroid-related protein receptor (PPR) and bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1a (Bmpr1a), osteoblasts that express N-cadherin form N-cadherin/β-catenin adhesion complexes with HSCs9. Osteoblasts also produce many essential molecules for HSC renewal and maintenance, such as osteopontin (OPN), thrombopoietin, annexin-2, and angiopoietin-112,13. Similarly, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 (CXCL12) in mesenchymal progenitor cells is required for the maintenance of HSCs and can maintain HSCs in an undifferentiated state14. These complexes may mediate the adhesion of hematopoietic stem cells within their niche15.

Osteoblast origin and cell lineage

The process of osteoblast formation involves a series of distinct stages and cell types within the osteoblast lineage. Osteoblast lineage cells include mesenchymal progenitors, pre-osteoblasts, osteoblasts, osteocytes, and bone-lining cells (Fig. 1). The exact origin of osteoblasts can vary depending on the life stage and the specificity of the local environment, and therefore, the naming of progenitor cells has always been controversial16. Skeletal stem/progenitor cells (SSPCs) can broadly include all immature precursor cells located within the bone and can differentiate into bone tissue-forming cell types16. This includes cartilage stem cells, recently found in growth plates17,18, fetal perichondrium cells which give rise to bone lines19, and periosteum progenitor cells, in endochondral bone development which is important in fracture repair20,21, as well as distinct reticular and perivascular stromal cell subpopulations in bone marrow, commonly referred to as bone marrow stromal cell (BMSC) populations, which seem to have lipogenic potential in some cases22,23.

During development, osteoblast formation proceeds via two distinct pathways: intramembranous ossification or endochondral ossification (Fig. 1). In mammals, intramembranous ossification primarily affects only a portion of the clavicle and the skull, whereas endochondral ossification controls bone formation throughout the skeletal system24. During intramembranous ossification, MSCs can directly differentiate into osteoblasts, while osteoblasts are indirectly formed during endochondral ossification through the formation of the periosteum, which contains immature osteoprogenitor cells25. Osteoblastogenesis during intramembranous ossification occurs through three main stages: mineralization, proliferation, and matrix maturation. On the other hand, endochondral ossification occurs in two steps: building cartilage templates in a nonvascularized environment and steadily replacing the cartilage template with bone. Through mesenchymal condensations, endochondral ossification constructs a framework for subsequent bones and leads to the mass production of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. Following the action of SOX9, condensing mesenchymal cells quickly transform into chondrocytes (Fig. 1), which will continue to proliferate and produce cartilage templates26. At this stage, the perichondrium forms a highly vascularized fibrous tissue adjacent to the cartilage template. In an area immediately adjacent to the pre-hypertrophic zone, the perichondrium produces the first osteoblasts in endochondral bones. Later, the perichondrium will develop into the bone collar and periosteum27.

During intramembranous ossification, lineage commitment of MSCs is dependent on the early activation of specific BMPs, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ), and Wnt signaling, with alkaline phosphatase (ALP), collagen type I (COL1A1), OPN, osteocalcin (OCN), and PPR among the markers most highly expressed during the differentiation of osteoblasts (Table 1; Fig. 1)15,25,28. After initial lineage commitment, an MSC will divide into an osteoprogenitor and an additional stem cell; this division is important to maintain frequent proliferative activity and self-renewal29. The newly formed pre-osteoblast is an intermediate cell that can express the MSC marker STRO1, ALP, PPR, and collagen type I and possesses an extensive capacity for replication; however, it has no capacity for self-renewal30. Located near newly synthesized osteoid cells, ALP, OPN, bone sialoprotein (BSP), and OCN are expressed by mature osteoblasts. The pre-osteoblast cell is responsible for bone deposition and has limited replication potential31. Terminal differentiation and permanent stoppage in cell division are the next crucial steps. Post-mitotic osteocytes are the final stage of the bone lineage. They are typically found separated in the bone and may be embedded in developing osteoid cells.

Osteoblast signaling

Several essential signaling pathways regulate osteoblast differentiation (Figs. 2, 3). Wnt, TGF-β, Hedgehog, and FGF signaling pathways are canonical pathways known to affect osteoblast differentiation. Additionally, Notch, Hippo, and NF-κB signaling also affect osteoblast differentiation.

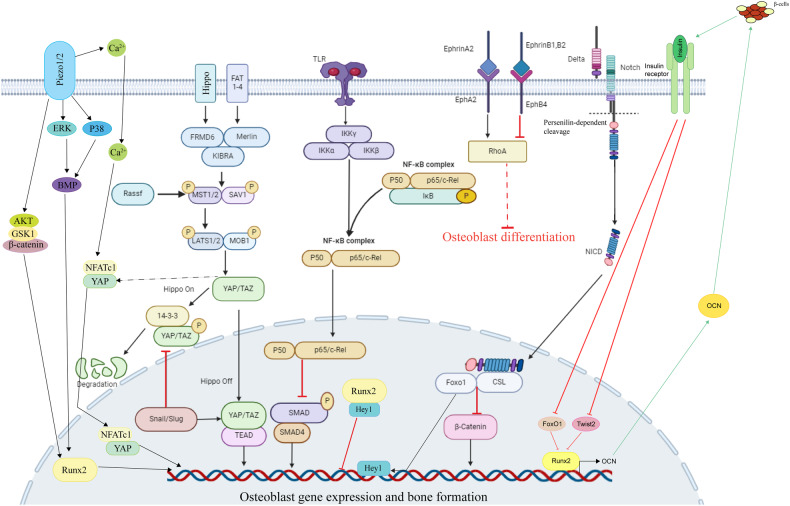

Fig. 3. Noncanonical signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation.

Notch, NF-κB, Hippo, Ephrin, and Piezo1/2 signaling pathways also play important roles in osteoblast differentiation. Osteoblast differentiation is inhibited by the Notch and NF-κB signaling pathways, with the Notch signaling pathway’s downstream factors NICD binding to CLS and inhibiting β-catenin. NICD/CLS/Foxo1 complex can promote Hey1 expression, then Hey1 can bind with Runx2 to inhibit Runx2 activity. When NF-κB signaling is stimulated, the P50 and P65 complex translocates into the nucleus and inhibits Smad protein activity. Hippo signaling is a crucial pathway in cell growth and development. The important downstream factors YAP/TAZ in Hippo signaling can regulate osteoblast differentiation-related gene expression. When Hippo signaling is in an “off” state, the YAP/TAZ complex will not be degraded and will translocate into the nucleus to regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression. The snail/slug complex can promote YAP/TAZ activity in nuclear and inhibit YAP/TAZ degradation in the cytoplasm. Ephrin signaling has different regulatory effects on osteoblast differentiation through different pathways and plays a specific role in the regulation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts. The EphrinA2 and EphrinB2 expressed on osteoclast membranes can interact with EphA2 and EphB4 expressed on osteoblast membranes to regulate osteoblast differentiation. Ephrin signaling regulated osteoblast-specific gene expression mainly through RhoA. EphrinA2 binds with EphA2 and promotes RhoA activity, while EphrinB1/2 binds with EphB4 and inhibits RhoA activity. When RhoA is activated, it will inhibit osteoblast differentiation. Piezo1/2 is a recently discovered pathway functioning in osteoblast differentiation. Piezo1/2 can regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression by regulating downstream pathways such as ERK and P38 and interacting with Hippo signaling. Piezo1/2 can regulate β-catenin activation to active Runx2 and regulate osteoblast gene expression. Piezo1/2 can also activate NFATc1 and YAP via calcium signal, and then NFATc1 and YAP can translocate into the nucleus and regulate osteoblast differentiation. Insulin signaling inhibits the production of FoxO1 and Twist2, which can inhibit the expression of Runx2 and Ocn. Ocn improves insulin sensitivity and energy expenditure through multiple mechanisms like activating to β-cells. The direct effect of osteocalcin as an insulin-sensitizing hormone is speculative and remains to be determined.

Wnt signaling pathway

Overview of Wnt signaling

The family of secretory glycoproteins known as Wnt contains numerous protein factors that are ligands of the 7-membrane-spanning frizzled (FZD) receptor family (Fig. 2). The secreted factors of the Wnt family are implicated in numerous cellular processes, such as regulating cell polarity, cell differentiation, cell proliferation and cell function. There are two different categories of Wnt proteins. The first type causes activation of canonical Wnt signaling by forming complexes among Wnt proteins, the low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein 5 or 6 (LRP5 or LRP6) and FZD32,33 (Fig. 2). Of note, LRP4 has been implicated in sclerosteosis and van Buchem disease due in part to its role in Wnt signaling, with deficiency of LRP4 in osteoblast-lineage cells causing higher cortical and trabecular bone mass in mutant mice, which is linked to increased bone formation and less bone resorption34. The second type of Wnt protein causes activation of the noncanonical pathway through a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism, where Wnt5a binds with FZD to activate heterotrimeric G proteins and subsequently raises intracellular calcium to promote osteoblast function35.

Both canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling are crucial for bone remodeling36,37. Wnt proteins, whether displayed on the cell surface or secreted, have the capability to engage osteoblasts via binding with the FZD/LRP5/6 complex38. The PTH1 receptor, which binds PTH and forms a complex with LRP5/6, can also activate the Wnt signaling in the absence of the Wnt ligand. Disheveled, Axin39, and Frat-1 proteins stimulate the signal by destroying the protein complex and inhibiting glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) function, resulting in reduced phosphorylation of β-catenin40 (Fig. 2). By hindering GSK3 activity, the stability of β-catenin is improved and Wnt signaling is turned on (Fig. 2). MiR-346 promotes osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting glycogen synthetase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), preventing β-catenin degradation in human BMSC41 (Fig. 2). Recent studies have shown that 1-Azakenpaullone, a highly selective GSK-3β inhibitor, is a potent inducer for osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human MSCs42. 1-Azakenpaulone significantly induces osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of human MSCs by activating Wnt signaling, leading to the up-regulation of Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), a key transcription factor that ultimately promotes osteogenic specific gene expression42. Once stabilized in the cytoplasm, β-catenin translocates to the nucleus to promote target gene expression. The nuclear partners of β-catenin are the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor/T cell factor (Lef/Tcf) family43,44. β-catenin substitutes Lef/Tcf corepressors, establishing heterodimers with Lef/Tcf proteins (Fig. 2). With the help of P300/CBP and other transcriptional co-activators, this heterodimer binds to DNA and promotes target gene transcription for osteoblast differentiation45 (Fig. 4).

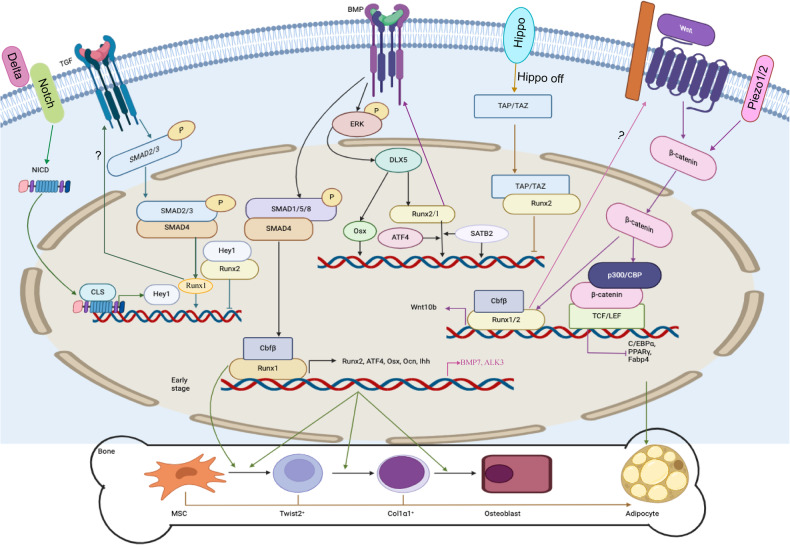

Fig. 4. Signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast cell lineage commitment, differentiation, and bone formation.

Among the many transcription factors that participate in osteoblast differentiation, the Runx family, Osx, ATF4, Cbfβ, and SATB2 are significant. Cbfβ binds to Runx family proteins to form heterodimers, improving Runx2’s and Runx1’s stability and subsequently facilitating Runx2 or Runx1 binding to target DNA sequences. Runx1 positively regulates osteoblast lineage gene expression at various stages of differentiation. Runx1 plays a significant role in postnatal bone homeostasis by binding to ATF4, Ocn, and Runx2 promoters to activate the corresponding genes and promote osteoblast early differentiation. Runx1 promotes BMP7 and Alk3 expression to regulate BMP signaling. How Runx1 can regulate Wnt10b and TGF-β signaling remains unclear. Runx1 can also regulate osteoblast-adipocyte lineage via inducing Wnt/β-catenin signaling, TGF-β signaling, and restraining adipogenic gene transcription. Cbfβ is also crucial in stimulating osteogenesis by inhibiting the expression of the adipogenesis regulatory gene C/EBPα and activating Wnt10b/β-catenin signaling. Wnt binds with FZD receptors, causing the ß-catenin accumulation. Pizeo1/2 can also regulate ß-catenin. ß-catenin then moves to the nucleus, in which it causes target genes to be transcribed by interacting with P300/CBP and TCF/LEF. TGF-β and BMP regulate transcription factors through SMAD proteins to activate Runx1 and Runx2 activity, and the SMAD itself can also regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression. BMP signaling can also activate Dlx5 through ERK and promote Runx2, ATF4, and Osx expression. When the Hippo signaling is at the “off” state, YAP/TAZ can translocate into the nucleus and bind with Runx2 to inhibit its activity. NICD1 in Notch signaling can translocate into the nucleus and promote the expression Hey1, which in turn inhibits Runx2 function by binding with Runx2. The activation of β-catenin and Runx2 will also inhibit the expression of C/EBPα, PPAR-γ, and Fabp4; these genes are important in adipocyte differentiation.

β-catenin degradation can be facilitated through its interaction with protein complexes consisting of APC, Axin, and GSK3 if Wnts are either not expressed or are unable to bind to the receptor (Fig. 2). GSK3 phosphorylates β-catenin, after which the phosphorylated form undergoes ubiquitination by the β-TrCP ubiquitin E3 ligase and subsequent degradation via the ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal system46 (Fig. 2). Pannexins3 (Panx3) can promote the degradation of β-catenin by activating GSK3β, thus inhibiting the activity of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and the differentiation process of osteoblasts47. In the nucleus, Tcf/Lef and its repressor bind to inhibit target genes downstream of the Wnt signaling. In the “off” state of Wnt signaling, characterized by low cytosolic and nuclear levels of β-catenin, osteoblast differentiation is reduced44 (Fig. 2). Similarly, promotion of APC degradation via genistein-induced autophagy initiated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation and β-catenin–driven osteoblast differentiation, rebalancing dysregulated osteogenesis within the femurs and tibias of OVX mice48. Taken together, these findings could indicate that targeting the degradation mechanisms for β-catenin may be a potential avenue for better treatment of diseases driven by improper osteoblast differentiation.

Wnt ligands can bind with a variety of inhibitors to limit pathway activation, like FZD-associated protein (sFRP) secretion and Wnt repressor SOST (Sclerosteosis gene product)49, Dickkopf (Dkk) family50, and Src (Fig. 2). These inhibitors like SOST and Dkk can bind to LRP5/6 and inhibit its coreceptor activity. Capable of interfering with canonical Wnt signaling, Dkk1 and Dkk2 bind to LRP5/6 and kremen (a transmembrane protein) (Fig. 2)51. The silencing of the FZD6 receptor influences osteoblast differentiation, restraining osteoblast differentiation through the canonical pathway of Wnt. Meanwhile, FZD4 silencing reduces the rate of osteoblast differentiation via reduced expression of Tcf/Lef52,53.

Conversely, the promotion of osteoblast differentiation through the stabilization of Wnt-signaling can be achieved through various mechanisms. The R-spondin family is comprised of four secreted glycoproteins (Rspo1–4) and functions to amplify Wnt signaling. Notably, Rspo3 variants are strongly linked to bone density54,55. A recent study indicated that in appendicular bones, insufficient Rspo3 haploid and loss of Rspo3 targeting in Runx2+ bone progenitor cells can lead to increased trabecular bone mass, osteoblasts, and bone formation numbers54. The inhibitory effect of Dkk1 on Wnt signaling activation and bone mass is compromised by Rspo3 deficiency54. Defects in Rspo3 result in the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling, which subsequently stabilizes β-catenin and activates Wnt signaling, thereby promoting osteoblastogenesis and bone formation54.

Wnt signaling performs various functions in different stages of osteoblast differentiation. Canonical Wnt signaling can enhance early osteoblast differentiation, while mature osteoblast mineralization induction is severely hampered by it56,57. During osteoblast differentiation, multiple Wnt signaling genes are changed, and endogenous Wnt signaling is suppressed58,59. Wnt16 can regulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling by antagonizing Wnt5a to suppress the non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway60. In a prior study, it was discovered that Wnt16 enhances the expression of osteoblast differentiation genes (BMPR1b, BMP7, and ENPP1), while simultaneously reducing the expression of specific osteoblast maturation and mineralization genes (ALP1 and RSPO2)61. However, another study found that Wnt16 positively regulates osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization60. Therefore, the mechanistic basis for how Wnt16 regulates osteoblast mineralization still needs further research.

Wnt canonical pathway

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway promotes bone formation by stimulating osteoblast development62–64. Bone formation and specific osteoblast gene expression are both enhanced by high levels of β-catenin62,65, while ectopic chondrogenesis and abnormal osteoblast differentiation resulted from conditional β-catenin knockdown at the initial stage of osteoblast development65–67 (Table 1). Additionally, Wnt is involved in all stages of bone development, as demonstrated by the process of bone formation exhibited by LRP5-deficient mice68–70. Altered bone mass was observed in mice with LRP5 deficiency71,72, indicating that Wnt signaling is crucial during bone development73,74. Furthermore, the functional acquisition of the LRP5 mutation increases Wnt signaling, leading to higher bone mineral density in mammalian models73,75–77 (Fig. 2).

Wnt-LRP5 signaling promotes bone formation in part by directly reprogramming glucose metabolism78. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) and protein kinase B (AKT) are activated by Wnt3a via LRP5 and ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate1 (RAC1), which causes the activity of glycolytic enzymes to increase78. In addition, the Warburg effect, induced by Wnt3a’s elevation of key glycolytic enzyme levels, can trigger aerobic glycolysis78. In vitro metabolic regulation aids Wnt-induced osteoblast differentiation and is linked to the bone-forming activity of LRP5 signaling in vivo78. Exosomes of adipose stem cells (ASCs-exos) have recently been found to promote osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, with ASCs-exos improving bone healing ability in a rat model of nonunion fracture repair79. ASCs-exos play a role in activating the Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling pathway and promoting osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs79. By activating the Wnt3a/β-catenin signaling pathway, ASCs-exos enhance the osteogenesis potential of BMSCs and promote bone repair and regeneration in vivo, providing a new direction for the treatment of diabetic fracture nonunion79.

Bipotential mesenchymal precursors undergo osteoblastogenesis stimulation and adipogenesis inhibition via canonical Wnt signaling. By enhancing osteoclastogenic transcription factors like Runx2 and Osx while inhibiting adipogenic transcription factors, Wnt10b induces osteoblast differentiation62. The inhibition of PPAR-γ and C/EBPα expression is one way through which Wnt10b promotes osteoblastogenesis62. C/EBPα is also an essential regulator in osteoclast differentiation80–82. Indeed, Wnt10b–/– mice showed reduced trabecular bone density and serum osteocalcin, further illustrating that Wnt10b is an endogenous regulator of bone formation62.

Wnt noncanonical pathway

Previous research has extensively studied how the canonical Wnt signaling pathway can influence osteoblast differentiation. However, the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway also plays a significant role in mediating osteoblast differentiation. In comparison to canonical Wnt signaling, the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway regulates osteoblast differentiation not through β-catenin but rather through various other transcriptional and signaling mechanisms.

Wnt5a

Wnt5a is a significant marker of noncanonical Wnt signaling, with Wnt5a inhibiting the expression of PPAR-γ through SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1 (SETDB1) to promote osteoblast differentiation83. Although TAZ (Table 1) is an important transcription factor that promotes MSC differentiation by trans-inhibiting PPAR-γ function, noncanonical Wnt signaling via Wnt5a activation does not appear to modulate TAZ expression during osteoblast differentiation83. Following Wnt5a-induced activation of noncanonical Wnt signaling, SETDB1 interacts with chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding protein 7 (CHD7) and phosphorylated nemo-like kinase (NLK) to form a multi-protein complex83. This complex methylates the histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) of the PPAR-γ promoter, resulting in chromatin inactivation and the failure of PPAR-γ to initiate transcription83. By suppressing the transformation of bone marrow MSCs into adipocytes via a reduction in PPAR-γ’s transcriptional effect, Wnt5a can stimulate osteoblast production83.

Wnt/calcium pathway

In the process of osteoblast differentiation, the Wnt/calcium pathway operates as a noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway. The Wnt/calcium pathway can raise intracellular calcium levels to activate calcineurin, protein kinase C (PKC), and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), which in turn induces the expression of activating protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factors. The combination of integrin receptors and collagen I may cause CaMKII to be activated in osteoblasts, resulting in ERK phosphorylation, thus promoting Runx2 activation and subsequent osteoblast differentiation84. Therefore, the noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway can also promote osteoblast differentiation by regulating the expression of Runx2, which is mechanistically similar to canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Wnt7b

In osteoblast precursors, the noncanonical Wnt pathway plays a role in promoting bone formation. This involves Wnt-mediated activation of G protein-linked phosphatidylinositol signaling, leading to the activation of G protein-linked protein kinase C δ (PKCδ). This process, facilitated by Dvl, remains unaffected by Dkk185. In mouse embryos, the elimination of either Wnt7b or PKCδ led to impaired bone formation85. Wnt 7b induces osteoblast differentiation via PKCδ (Fig. 2)85. Wnt-induced PKC activation requires the Gq subunit, which is required for osteoblast differentiation induced by Wnt7b. Wnt7b activates Runx2 through PKCδ signaling to regulate osteoblast-specific gene expression. Although PKCδ signaling activates osteoblast differentiation, in vitro experiments demonstrated that Wnt7b or PKCδ mutant mice can still form bone85. This suggests that this pathway can act as a mechanism to augment other osteogenic signaling pathways, but it may not be enough for osteoblast differentiation85.

Prior research has suggested a connection between increased glycolysis and osteoblast differentiation triggered by Wnt signaling86. However, direct genetic confirmation of the role of glucose metabolism in Wnt-induced bone formation has been lacking. A recent study revealed that overexpression of Wnt7b significantly enhanced bone formation, yet this effect was largely negated in the absence of Glucose Transporter 1 (Glut1), despite the transient deletion of Glut1 itself not affecting normal bone accrual87. Wnt7b was also observed to elevate Glut1 expression and glucose consumption in primary cultures of osteoblast lineage cells, with Glut1 deletion impairing osteoblast differentiation in vitro87. Thus, Wnt7b appears to contribute to bone formation partly by stimulating glucose metabolism in osteoblast lineage cells87.

Role of β-catenin in osteoblast differentiation

β-catenin is required for mature osteoblast differentiation (Table 1)65,66,88. Without β-catenin, osteoblast progenitors will instead develop into chondrocytes, with chondrogenic interstitial precursor fate being determined by β-catenin activity65,66. Runx2 promoter activity and expression are both enhanced by β-catenin/TCF189. Experimental findings have shown that mice lacking β-catenin develop osteopenia (Table 1), while bone mass was increased when β-catenin function was rescued in osteoblasts67,90. Previous work in our lab also found that Cbfβ/Runx2 complex promotes Wnt10b/β-catenin to improve osteoblast differentiation and inhibit c/ebpα expression to inhibit lineage switch into adipocytes91.

Regulation of Wnt signaling pathway

MTSS1 plays a significant role in osteoblast differentiation and bone homeostasis by controlling Src-Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In osteoblast differentiation, Src acts as a negative regulator by phosphorylating LRP6 at several conserved tyrosine residues. This phosphorylation disrupts the removal of LRP6 from the osteoblast cell surface and the formation of LRP6 signalosomes, thereby inhibiting canonical Wnt signal transduction92. When MTSS1 increases, Src diminishes the content of phosphorylated-GSK3β, non-phospho-β-catenin, and transcription factor 7 like 2 (TCF7L2)93. Thus, Src inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation in osteoblasts, whereas MTSS1 stimulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by inhibiting the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src.

Similar to MTSS1, Tenascin-C also positively regulates Wnt signaling. Deletion of Tenascin-C significantly inhibits osteoblast differentiation, indicating its role as a positive regulator of Wnt signaling94. Likewise, β-catenin overexpression can significantly reverse the inhibition of osteoblast differentiation that is caused by Tenascin-C deficiency94. Tenascin-C can bind to DKK-1, the primary inhibitor of Wnt signaling, suppressing DKK-1 function94. Previous work has shown that DKK-1 expression is increased when Tenascin-C is knocked down by siRNA, thereby reducing the transcriptional activity of Wnt signaling94.

TNF receptor-associated factor 3 (TRAF3), a TNF receptor family adaptor protein, positively regulates osteoblast differentiation95. Mice deficient in TRAF3 exhibited reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption, displaying a phenotype indicative of early-onset osteoporosis95. It was also discovered that TRAF3 promoted osteoblast formation and prevented the degradation of β-catenin in MSCs96. TGF-β1, which is released when bone resorption occurs, induces TRAF3 degradation and thus inhibits osteoblast differentiation through GSK-3β-mediated β-catenin degradation96.

Hormones can regulate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by controlling important proteins in Wnt signaling. In osteoblast progenitors that express Osterix1 (Osx1), Wnt/β-catenin signaling is boosted by estrogen receptor α (Erα), causing an increase in periosteal cell proliferation and differentiation97. Estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα), in conjunction with the coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator (PGC-1α), acts as a positive regulator of Wnt signaling in osteoblast differentiation. This occurs via a cell-intrinsic mechanism that remains unaffected by β-catenin nuclear translocation98. Activated ERRα can bind with the TCF/LEF complex and stimulate osteoblast-specific gene expression similar to that induced by β-catenin98. Thus, it can be understood that TCF/LEF is activated to promote the expression of osteoblast-specific genes in the absence of β-catenin nuclear translocation.

TGF-β and BMP signaling

TGF-β and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the TGF-β superfamily, playing crucial roles in osteoblast differentiation99,100. There are two main types of TGF-β and BMP signaling: one is Smad-dependent and the other is Smad-independent (Fig. 2)101. There are three Smad types. The first is the receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads), which can either be triggered by BMPs (Smad1/5/8) or activated by TGF-β (Smad2/3). The second is co-Smads, such as Smad4, which can be co-mediated by BMP and TGF-β. The third is inhibitory Smads, like Smad6 and Smad7, which can negatively regulate BMP and TGF-β signaling (Fig. 2)102,103. R-Smads and co-Smads combine to form a complex that moves to the nucleus and controls osteoblast-specific gene expression101. Runx2 expression is not directly induced by the BMP signaling pathway104, but it can be induced by promoting distal-less homeobox 5 (DLX5) expression (Fig. 2)105,106.

Overview of TGF-β signaling

TGF-β signaling pathways govern osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation, influencing bone formation at different stages of development and within disease pathology. Smad proteins are critical in TGF-β signaling pathways (Fig. 2)102,107. In conjunction with Smads, TGF-β signaling regulates osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation108,109. TGF-β signaling primarily activates Smad2/3 to regulate osteoblast differentiation. However, TGF-β can also bind to ALK-1, transducing SMAD-1, 5, and 8 signaling, typically activated by BMPs (Fig. 2)110,111. During the early stage of differentiation, TGF-β signaling promotes osteoprogenitor proliferation and osteogenesis. However, at later stages, it inhibits bone formation102. Previous work in our lab also found that TGF-β1 signaling pathway also is critical in tooth root development and odontoblast differentiation112. Moreover, in vitro studies have demonstrated that TGF-β, along with SMAD3 and SMAD2, inhibits osteogenesis113–116. Excessive TGF-β signaling was also found to be involved in the pathogenesis of osteogenesis imperfecta in mouse models, with anti-TGF-β treatment correcting altered bone phenotype117. These findings were validated in a small clinical study, where the administration of the monoclonal antibody fresolimumab to participants showed an absence of severe side effects. Furthermore, it was noted to enhance the areal bone mineral density in the lumbar spine of individuals diagnosed with osteogenesis imperfecta type IV118. Deletion of Transforming growth factor beta receptor 2 (TGFBR2), the sole type II receptor for TGF-βs, effectively abolishes TGF-β signaling. This deletion leads to severe defects in calvarial, appendicular, and axis bones119.

TGF-β signaling regulation

Higenamine (HG) has been recognized as a promising candidate for treating osteoporosis through its influence on SMAD2/3 signaling. A novel target for HG has been identified in IQ motif-containing GTPase activating protein 1 (IQGAP1), with HG binding to the Glu-1019 site of IQGAP1, facilitating its osteogenic effects120. Through this mechanism, HG induces Smad2/3 phosphorylation and modulates the Smad2/3 pathway by inhibiting Smad4 ubiquitination120. Consequently, HG emerges as a potential novel small-molecule drug to stimulate bone formation in osteoporosis via the Smad2/3 pathway120.

Recent research has suggested that intraflagellar transport 20 (IFT20) modulates osteoblast differentiation and bone formation by regulating the TGF-β signaling pathway121,122. IFT20 controls MSC lineage allocation by regulating glucose metabolism during bone development123. In MSCs, the absence of IFT20 results in a significant reduction in glucose tolerance and inhibits glucose uptake, lactic acid production, and ATP production123. Deleting IFT20 markedly reduced the signaling activity of TGF-β-Smad2/3, decreased the binding activity of Smad2/3 to the Glut1 promoter, and down-regulated Glut1 expression123. These findings suggest that IFT20 plays a vital role in preventing the allocation of MSC lineages to fat cells through the TGF-β-Smad2/3-Glut1 axis123. Moreover, GATA binding protein 2 (GATA2), necessary for HSC differentiation, can impede osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting Smad1/5/8 activation124.

Overview of BMP signaling

BMP signaling (an evolutionarily conserved group of signaling proteins belonging to the TGF-β superfamily) also has an effective role in osteoblast differentiation. Indeed, BMPs display effective osteogenic effects, similar to the physiological effect mediated by TGF-β125. BMP-2, -4, and -6 are signaling molecules that are highly expressed in both osteoblast cultures and bone tissue126. BMP molecules like BMP-2, -6, -7, and -9 aid in bone formation127. Of note, BMP3B negatively regulates bone formation128, in which BMP3B and BMP-2 may antagonize each other through competition with the availability of Smad4129.

Although BMP signaling can easily regulate the differentiation of osteoblasts through Smad proteins, it is also capable of this regulatory function by activating other signaling pathways controlled by Smad proteins. Prior research indicates that BMP-2 facilitates the interaction between Dvl-1 and Smad1, resulting in the inhibition of β-catenin nuclear accumulation130. Because Dvl-1 is an important inhibitor of GSK-3β, β-catenin is degraded when Dvl-1 binds to Smad1, thus inhibiting the activity of the Wnt signaling pathway130. BMP-2 can inhibit the proliferation of the Wnt signaling in this way, thus enabling MSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts130. Persicae semen (PS) originates from the dried and mature seeds of peach (Prunus persica, L.). PS facilitates mineralization and up-regulates Runx2 via BMP-2 and Wnt signaling pathways. Consequently, this leads to the expression of various osteoblast genes, including Alp, bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (Bglap), and integrin binding sialoprotein (Ibsp)131. Research has demonstrated that PS promotes fracture recovery by enhancing osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Consequently, it could serve as a potential treatment option for patients with fractures131.

Aside from Smad-dependent pathways, BMP can regulate osteoblast differentiation through various other signaling mechanisms. BMP2 stimulates the expression of ALP and OCN by activating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway132,133. By triggering Runx2 expression and activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), BMP2 promotes osteoblast differentiation through the protein kinase D (PKD) pathway134. DLX5 has been shown to be a BMP2 signaling upstream target and can increase Runx2 expression downstream (Fig. 2)135. By activating DLX5 through the p38 signaling pathway, BMP2 can also induce Osx expression in addition to Runx2 expression (Fig. 2)136. In the bone microenvironment, BMP and other growth factors, like IGF-I, can co-activate Osx expression137. Recent research has also revealed that BMP2 can inhibit the expression and activity of salt-inducible kinase 1 (SIK1) through protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent pathways, thereby promoting osteogenesis138. SIK1 functions as a critical regulator, suppressing preosteoblast proliferation and osteoblast differentiation. The repression of SIK1 is crucial for facilitating BMP2 signaling in osteogenesis138.

BMP signaling regulation

The regulation of BMP signaling concerning osteoblast differentiation is influenced by numerous factors, all of which play distinctive roles in osteogenic processes. For instance, LIM homeobox transcription factor 1 beta (Lmx1b) hinders osteoblast differentiation by negatively controlling BMP2139. Lmx1b can decrease Runx2’s recruitment in the promoter sequence of the target gene and when combined with Runx2, inhibiting Runx2 activity139. Through the BMP2 promoter’s Tcf/Lef response elements, cWnt signals can trigger BMP2 activity140. BMP3 is a negative feedback regulator of osteoblast generation that is induced by cWnt, with decreased BMP3 expression possibly increasing the activity of the cWnt signal, encouraging osteoblast differentiation141. Hey1, which is involved in Notch signaling, can also be expressed by BMP2 signaling (Table 1)142. Particularly noteworthy is that kisspeptin-10 (KP-10), acting as a ligand for GPR54, has previously been identified to initiate the binding of NFATc4 to the BMP2 promoter via its interaction with GPR54. As a result of this interaction, BMP2 upregulates the expression of osteogenic genes by phosphorylating Smad1/5/9, thereby stimulating osteoblast differentiation in vitro143. Subsequent research unveiled that KP-10 encourages osteogenic differentiation of osteoblast progenitors and inhibits bone resorption in human cultured cells, while its administration to healthy male subjects resulted in a notable increase in the bone formation marker osteocalcin without corresponding effects on resorption markers144. Overall, the regulation of BMP2 activity and its signaling pathways represent a potential therapeutic target for conditions such as osteoporosis and other pathologically similar disorders.

Ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation also affects BMP signaling, with Smurf proteins regulating the interaction between osteoblasts and osteoclasts145,146. When Smurf1 is deficient, MEKK2 builds up, which triggers JNK activation, a necessary and sufficient event for osteocyte BMP sensitization146,147. Studies have demonstrated that Smurf2-deficient mice exhibit severe osteoporosis148. Osteoblasts deficient in Smurf2 exhibit elevated expression of RANKL. This phenomenon is attributed to Smurf2’s regulation of Smad3’s ubiquitination status and its disruption of the interaction between Smad3 and vitamin D receptors, ultimately resulting in alterations in RANKL expression148.

Hedgehog signaling

Indian Hedgehog (Ihh)

Hh signaling plays an important role in cell proliferation and differentiation, and there are three Hedgehog homologs known to exist in mammals: Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), (Ihh), and Desert Hedgehog (Dhh). In cells gathered from mutant mice lacking smoothened (Smo), an Hh signal, osteoblastic differentiation is impossible149. As such, it is clear that in vitro mesenchymal and bone-forming cells rely heavily on the activity of Smo and the Hh signaling pathway (Fig. 2)149. Previous studies have demonstrated that Ihh is important in chondrocyte differentiation150,151. Ihh is produced by hypertrophic pre-chondrocytes, a group of cells in the inner perichondrium where osteoblast progenitors first appear149,152. The close proximity of these cell types shows the significant and interdependent effect of Ihh signaling on both osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation153. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that osteoblast differentiation is compromised in mice lacking Ihh, and there is a deficiency in Runx2 expression. These findings suggest that Ihh signaling is capable of initiating osteoblastogenesis154. Additionally, a variety of mesenchymal and bone-forming cells have been stimulated in vitro to develop into osteoblasts by Ihh155,156.

In vitro studies have revealed that Speckle-type POZ protein (Spop), a component of the Cullin-3 (Cul3) ubiquitin ligase complex, positively regulates Hedgehog signaling157,158. Spop-deficient mutant mice exhibited defects in chondrocyte and osteoblast differentiation158. Parathyroid hormone-like peptide (PTHLH) expression was diminished in Spop mutants, while GLI family zinc finger 3 (Gli3) repressor form expression was up-regulated and GLI family zinc finger 2 (Gli2) expression remained unchanged, demonstrating that the Hh signaling was impaired159. Consistent with this finding, the Spop mutant’s skeletal defects were greatly ameliorated by decreasing Gli3 dosage159. A reduction in Gli3 dosage averted the formation of brachydactyly and osteopenia caused by Spop loss159. Therefore, Spop is an important positive regulator of Ihh signaling and skeletal development159.

Shh

The association between focal adhesion kinase (FAK) Tyr (397) expression and Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) expression suggests a potential link between FAK-regulated Osterix and the early differentiation of osteoblasts160. However, to better understand how FAK is controlled at the end of osteoblast differentiation, more research is needed. Purmorphamine, an Hh agonist, is a 2,6,9-trisubstituted purine that targets Smo transmembrane proteins161. The expression of Hh mediators such as Smo, patched 1 (PTCH1), Gli1, and Gli2 can be increased by purmorphamine (Fig. 2). Runx2 and BMP expression is also increased after Hh is activated by purmorphamine162.

From a clinical perspective, Shh has been implicated in the survival of tumor metastases. Research has suggested that signal peptide-CUB domain-EGF-related 2 (SCUBE2) operates in an autocrine fashion on tumor cells, releasing Shh that remains bound to the cell membrane163–166. This mechanism initiates the activation of Hedgehog signaling, consequently prompting the differentiation of osteogenic cells166. Notably, osteoblasts play a role in this mechanism by secreting collagen, which, in turn, activates the inhibitory leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 (LAIR1) signal in natural killer (NK) cells166. This cascade ultimately results in immune suppression and promotes the survival of tumor cells within the bone166.

Regulation of Hedgehog signaling

Pregnane X receptor (PXR) inhibits Hh signaling inducer genes like Gli1 and hedgehog-interacting protein (Hhip) while also inducing the expression of Hh signaling suppressor genes like cell adhesion associated (CDON), BOC cell adhesion associated (BOC), and growth arrest-specific 1 (GAS1)167. After treatment with Smo agonists, osteoblast differentiation and Gli-mediated transcriptional activity was significantly restored when Smo-mediated signaling was activated in these cells167. During osteoblast differentiation, Hh signaling significantly increases insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) expression, which triggers the mTORC2-AKT signaling cascade. In turn, IGF2-AKT signaling stabilizes full-length Gli2, thereby enhancing the output of Hh transcriptional activation168,169.

In osteoblasts, the transmembrane protein SLIT and NTRK-like protein-5 (Slitrk5) are negative regulators of Hh signaling with a few known functions170. Osteoblasts exhibit a distinctive expression pattern of Slitrk5, where overexpression of Slitrk5 in osteoblasts impedes the activation of targeted genes involved in Hh signaling. Conversely, Slitrk5 deficiency in vitro enhances Hh signaling171. Slitrk5 has an extracellular domain that binds to hedgehog ligands and an intracellular domain that interacts with PTCH1171. Through binding with hedgehog ligands and PTCH1, Slitrk5 can inhibit Hh signaling activation, thus reducing osteoblastic differentiation.

Interaction between Hh signaling and Wnt signaling

The interplay between Hh signaling and Wnt signaling is intricate. Previous research has demonstrated that in Ihh-knockout embryos, β-catenin is not translocated into the nucleus and that the Wnt canonical signaling target genes are not expressed88. Thus, the Wnt signaling pathway can only be activated, in part, due to the presence of Hh signaling. Hh signaling also affects how Wnt9a and Wnt7b are expressed, where a noted decrease in their expression accompanies Ihh knockout88. Alternatively, Hh and Wnt signaling pathways could have intracellular crosstalk through common regulators, such as the fusion repressor172 and GSK3173,174. Some studies have demonstrated that BMP is important for Hh-actuated osteoblast differentiation, in addition to Hh’s interaction with the Wnt signaling pathway175,176. For example, during the development of long bones, Ihh and BMP signals are jointly regulated to promote the differentiation of osteoblasts149. Therefore, studying the interaction between Hh signaling and other signaling pathways could provide a new understanding of the regulatory process behind osteoblast differentiation.

FGF signaling

Overview of FGF signaling

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are a series of secreted peptides that control many developmental processes and are essential for controlling endochondral and intramembranous ossification (Fig. 2)177. For instance, craniosynostosis — a condition that presents with the early onset of osseous occlusion of the cranial suture — is usually acquired via mutations in FGF receptors 1-3178,179 (Fig. 2). During growth plate development, both FGF receptor 1 (Fgfr1) and FGF receptor 2 (Fgfr2) are expressed in the condensing stroma, contributing to cartilage formation180. Reserve chondrocytes express Fgfr2, and proliferating chondrocytes down-regulate it, while hypertrophic chondrocytes express Fgfr1180. At the final developmental stages, the tissues that produce osteoblasts and cortical bone, the perichondrium and periosteum, express both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2180. Osteoprogenitor cells typically use Fgfr1 signaling to encourage differentiation, but matured osteoblasts use it to prevent further differentiation180. As a result, Fgfr1 signaling influences osteoblast maturation in a stage-specific manner180. Unlike Fgfr1/2, Fgfr3 significantly regulates proliferating chondrocytes’ growth and differentiation181 while also mediating cortical thickness and bone mineral density in differentiated osteoblasts182,183. As such, human craniosynostosis and achondroplasia syndromes are primarily caused by Fgfrs mutations177,184,185. Additionally, exogenous FGF7 stimulates embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation by activating ERK-Runx2 signaling but does not affect the proliferation of osteoblasts186. FGF8 can stimulate Connexin 43 (Cx43) expression, which mainly occurs in osteoblasts and regulates osteoblast proliferation and differentiation187. Therefore, by controlling Cx43 expression, FGF8 can influence osteoblast differentiation. Furthermore, research indicates that FGF18 can also positively regulate osteoblast differentiation by mediating Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 activation via ERK1/2 and PI3K (Fig. 2)188,189.

Role of FGF signaling in osteoblast differentiation

Through phosphorylation of the MAPK signaling pathway, FGF2 can stimulate Runx2 expression, indicating that FGF2 participates in osteoblast differentiation190. Additionally, FGF2 can regulate the Wnt signaling pathway’s activity. Expressions of Wnt10b, LRP6, and β-catenin were reduced in FGF2-deficient BMSCs in vitro, and the inactivated GSK3β was also significantly reduced, suggesting that β-catenin degradation is possible191. By directly or indirectly controlling GSK3’s activity to regulate β-catenin stability, FGF2 may influence the Wnt signaling191.

The differentiation of osteoblasts also depends on FGFR. For example, Fgfr2-deficient mice exhibit a phenotype of decreased bone mineral density192. Different ligands of Fgfr2 include FGF7 and 10 (which are capable of activating FGFR2b) and FGF2, 4, 6, 8, 9 (which are capable of activating Fgfr2c)193,194. Adult Fgfr3-deficient mice displayed osteopenia, indicating that Fgfr3 also participates in osteoblast differentiation182. FGF18 can act as a physiological ligand for Fgfr3 to co-regulate osteoblast differentiation195. Furthermore, FGF18–/– mice exhibited diminished endochondral and intramembranous bone formation, indicating that FGF18 can promote osteoblast differentiation independently of Fgfr3195. Moreover, FGF signaling has been implicated in cranial development, as mutations in FGFR2 have been linked to the autosomal dominant condition Crouzon syndrome. Mouse strains harboring the FGFR2 mutation (p.Cys342Arg) have demonstrated an enhancement in the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells. This enhancement is achieved through the upregulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-Erk1/2 signaling pathway196. Furthermore, the FGFR2 p.Cys342Arg mutation increased oxidative phosphorylation and altered mitochondrial dynamics from fusion to fission in MC3T3-E1 cells. This shift facilitated osteogenic differentiation and contributed to craniosynostosis in Crouzon syndrome196. A recent study showed that the stability of FGFR2 is maintained by OTU Deubiquitinase, Ubiquitin Aldehyde Binding 1 (OTUB1)197. OTUB1 diminishes the E3 ligase activity of Smurf1, which mediates FGFR2 ubiquitination, by hindering the binding of Smurf1 to E2197. When OTUB1 is absent, Smurf1 excessively ubiquitinates FGFR2, leading to its degradation in the lysosomes197. These discoveries suggest that OTUB1 actively participates in regulating osteogenic differentiation and mineralization in bone homeostasis by modulating the stability of FGFR2. This highlights OTUB1 as a potential therapeutic target for mitigating osteoporosis197.

Hereditary hypophosphatemic disorders are also associated with FGF signaling pathways, stemming from excess FGF23 — a phosphate (Pi)-regulating hormone produced by bone — which results in impaired skeletal growth and osteomalacia. A recent study explored the impact of Pi repletion and bone-specific deletion of FGF23 on bone and mineral metabolism in the dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 (Dmp1) knockout mouse model of autosomal recessive hypophosphatemic rickets (ARHR)198. The bone defects observed in Dmp1 knockout mice are only partially attributable to FGF23-induced hypophosphatemia198. The study proposed that simultaneous restoration of DMP1 levels and inhibition of FGF23 could effectively rectify mineral and bone disorders associated with ARHR. Moreover, furin demonstrated the ability to cleave FGF23 in vitro, suggesting a potential therapeutic avenue198. Indeed, inactivation of furin in osteoblasts and osteocytes increased circulating intact FGF23 by 25%199 without significantly impacting serum phosphate levels. Therefore, therapeutically targeting excess FGF23 in patients suffering from hereditary hypophosphatemic disorders could represent a novel treatment modality.

Regulation of FGF signaling

Engrailed homeobox 1 (En1) can regulate FGFR-mediated signaling. ERK activation is inhibited when En1 is mutated, and the ERK activation is confined to mature intracranial osteoblasts of the wild-type skull200. The outer periosteal osteoblasts affected by En1 ablation lost the FGF target gene sprouty RTK signaling antagonist 2 (SPRY2)200. P38, MAPK, and PKC, the effectors of FGF signaling known to influence osteoblast differentiation, may also be influenced by En1200–202. En1 and FGF’s coordination of osteoblast differentiation will be better understood if these regulatory pathways are precisely described in a spatiotemporal manner.

The Sprouty family functions as an inhibitor of FGF signaling (Fig. 2). Basic FGF stimulation causes Sprouty2 expression to rise to high levels203. The increased presence of Sprouty2 directs ERK1/2 phosphorylation after basal FGF activation and Smad1/5/8 after BMP activation (Fig. 2)203. Expressions of Ocn, ALP, and Osterix mRNA were all inhibited by Sprouty2. Additionally, osteoblast matrix mineralization was stifled by Sprouty2. By inhibiting the expression of markers in differentiated osteoblasts, like Runx2 and ALP, and reducing FGF-ERK1/2 and BMP-Smad signaling, osteoblast differentiation and proliferation are negatively regulated by Sprouty2203.

Noncanonical signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation

Ephrin signaling

Overview of Ephrin signaling

Ephrins have bidirectional signal transduction capabilities. This class of signaling proteins falls into two categories: class A (ephrins A1 through A5), which bind to GPI-anchored EphA receptors (A1 through A10), and class B (ephrins B1 through B3), which bind to EphB tyrosine kinase receptors B1 through B6204. The interaction between Ephrin B and EphB, a transmembrane protein with a cytoplasmic domain, facilitate bidirectional signaling in cells. EphrinB2 from osteoclasts and EphB4 from osteoblasts, for instance, combine to create the signal between the two cells205. EphrinB2 on the surface of osteoclasts mediates EphB4 activation and promotes osteoblast differentiation206 (Fig. 1). In contrast, activation of EphrinB2-fold EphB4 on the surface of osteoclasts inhibits C-Fos/NFATc1 signaling of osteoclasts, thereby preventing osteoclast differentiation206. EphB4 signaling can prompt osteoblasts to express transcription factors like DLX5, Osx, and Runx2, underscoring the significance of Ephrin signaling in osteoblast differentiation25. Additionally, the inactivation of ras homolog family member A (RhoA) in osteoblasts may be required for Ephrin signaling to promote osteoblast differentiation207 (Fig. 3), with a study finding that suppression of osteoblast differentiation by EphrinA2(EfnA2)-EphA2 is mediated by increased RhoA activity208.

Ephrin signaling regulation

The effects of stage-specific EphrinB2 deletion on bone strength vary. The early loss of EphrinB2 in osteoblasts results in osteoblast apoptosis, delayed onset of mineralization, and increased bone flexibility. Subsequent deletion of EphrinB2 in osteocytes targeted by the cell can lead to a fragile bone phenotype and heightened osteocyte autophagy209. When drugs were administered to cultured osteoblasts to prevent EphrinB2 from interacting with EphB4, the final stages of osteoblast differentiation and mineralization were repressed210. When inhibiting the interaction of EphrinB2 with EphB4 in vivo, early-stage osteoblast numbers increased while late-stage osteoblast numbers decreased, suggesting the existence of an EphrinB2:EphB4-dependent checkpoint in the process of osteoblast differentiation210. When targeting this EphrinB2:EphB4 checkpoint, the final osteoblast differentiation is blocked, interrupting the initiation of mineralization210. Therefore, these studies suggest that this crucial checkpoint controls the onset of bone mineralization during the late stage of osteoblast differentiation.

Additionally, in osteoblast lineages, the interaction between EphrinB1 and EphB2 impacts the expression from Runx2 to Osx, whereas the interaction between EphrinB2 and EphB4 allows for ALPl expression210. The interaction between EphrinB1 and EphB2 improves their function in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation211. EphrinB1 is necessary for early osteoblast marker expression like Osx and Runx2, with TAZ — a transcriptional coactivator with a PDZ-binding motif — causing Osx expression when translocated into the nucleus through stimulating EphrinB1 reverse signaling with aggregated EphB2211. In the osteoblast lineage, the interaction between EphB2 and EphB4 not only facilitates the differentiation of late osteoblasts but also prevents the formation of osteoclasts211.

The TGF-β1-Scx-EfnA2 axis can negatively regulate periodontal ligament (PDL) tension-induced osteoblast differentiation. TGF-β1-Smad3 signaling and EfnA2 are upstream and downstream regulators of scleraxis (Scx) in PDL cell response to tension, respectively212. Previous work has shown that Scx knockdown completely inhibits tension-induced EfnA2 expression, suggesting that tension-induced Scx inhibits PDL osteoblast differentiation by inducing EfnA2 expression212. This example of the co-regulation of osteoblast differentiation by coordinating the TGF-β and Hh signaling pathways exemplifies the importance of studying the intersection of various signaling pathways of osteoblast differentiation.

TLR/NF-κB signaling

Overview of TLR/NF-κB signaling

RelA (p65), RelB, cRel, NF-κB1 (P50), and NF-κB (P52) form the components of NF-κB signaling, usually kept sequestered by κB inhibitors within the cytoplasm213 (Fig. 3). During bone repair, inflammation is common and has been shown to prevent bone regeneration214. Osteoblast differentiation was inhibited by NF-κB signaling stimulation in previous research215. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-7 (IL-7) facilitate NF-κB activation and hinder osteoblast function in osteoporosis213. Furthermore, TNF-α and IL-1 can regulate osteoblast differentiation by down-regulating the promoter function of osteocalcin, a key gene in osteoblasts214,216. The expression of those cytokines is elevated when NF-κB signaling is stimulated, which will inhibit osteoblast differentiation217.

TLR/NF-κB signaling regulation

IKK-NF-κB stimulation promotes β-catenin ubiquitination and degradation through Smurf1 and Smurf2, inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway and stimulating Runx2 degradation (Fig. 3). Furthermore, TNF can induce p65 to bind to Smurf1 and Smurf2 promoters in MSCs215. Therefore, TNF may hinder osteoblast differentiation by activating NF-κB signaling. In the healing of occlusion injuries in rodents, the levels of β-catenin and Runx2 decreased alongside increased expression of p65 and IκBα215. However, after hindering IKK-NF-κB signaling, there was a significant increase in the expression of β-catenin, OCN, and Runx2215. Thus, IKK-NF-κB activation is involved in the degradation of β-catenin, ultimately preventing osteoblast differentiation and bone formation215. Similarly, melatonin was found to counteract the activation of the NF-κB pathway by inhibiting TNF-α, thereby reducing osteogenic differentiation and inflammation in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs)218.

Rocaglamide-A, a suppressor of NF-κB signaling, inhibits phosphorylation of NF-κB to promote osteoblast differentiation219. Conversely, p65 overexpression prevents the promotion of osteoblast differentiation by rocaglamide-A219. Rocaglamide-A inhibits p65 protein phosphorylation and the accumulation of p65 in the nucleus, reducing the transcriptional activity for NF-κB219. According to this work, the NF-κB p65 protein is engaged with the enactment of the NF-κB signaling, and recaglamide-A can forestall the NF-κB inhibitory impact on osteoblast differentiation by preventing the phosphorylation of p65219.

Osteoblasts’ autophagy-related function changes significantly when the NF-κB signaling pathway is disabled, demonstrating a possible connection between the two mechanisms220. However, according to some studies, NF-κB appears to play two roles in autophagy. NF-κB activation has the potential to encourage autophagy in some kinds of cells, such as myocardial cells221, and can also hinder autophagy in other cells like porcine granulosa cells220,222. Therefore, the mechanism of NF-κB in the regulation of autophagy during osteoblast differentiation still needs further research.

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is also a key factor in NF-κB signaling, with osteoblast expression of TLR4 necessary to activate the NGF-TrkA signaling required for stress-induced bone formation223,224. For example, in TLR4-conditioned knockout mice with normal adult bone mass and strength, loss of TLR4 signaling significantly reduced lamellar bone formation after stress loading225. Inhibition of TLR4 signaling decreased the expression of Ngf in primary osteoblasts225. Bone RNA sequencing in TLR4-conditioned knockout mice and wild-type pups revealed dysregulated inflammatory signaling three days after mechanical osteogenic loading, revealing the important role of osteoblast TLR4 in bone adaptation to mechanical forces225.

Notch signaling

Notch is cleaved by ADAM, a disintegrin and γ-secretase complex containing presenilin 1 or 2 that is formed by Notch ligand interactions226. Upon cleavage, the cytoplasmic Notch intracellular domain (NICD) is liberated and translocated to the nucleus (Figs. 3, 4)226. There, it forms a complex that controls gene transcription via binding with CSL family members226. This complex can activate HEY1 expression, with HEY1 then binding to Runx2 to prevent osteoblast differentiation (Fig. 4)227. NICD can block NFAT signaling by interacting with Foxo1, which also results in the inhibition of osteoblast generation. NICD also impedes Wnt/β-catenin signaling228. Hes1 is one of the downstream target genes of the Notch signaling pathway228,229 (Table 1). Hes1 silencing in vitro suggests that NICD inhibits Wnt/β-catenin signaling primarily through Hes1, where the binding of Hes1 to LEF-1 or transducin-like enhancer protein (TLE) may inhibit Wnt signaling228,229.

Notch signaling exhibits a bidirectional effect on osteoblast differentiation, as it can either inhibit or promote osteoblast differentiation depending on the stage of osteoblast differentiation and the timing of Notch activation230. Studies have shown that activation of Notch signaling can promote the mineralization process of osteoblasts231,232, while it has also been shown that overexpression of Notch1 can inhibit osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway233. It was shown that Notch1 not only inhibits terminal osteoblast maturation but also promotes immature osteoblast formation234. Moreover, it was observed that Notch signaling enhances the effectiveness of BMP9-induced BMP/Smad signaling, leading to an upregulation in the gene expression of critical osteogenic factors induced by BMP9 in MSCs, such as Runx2, Colla1, and inhibitor of differentiation234.

Forkhead box protein O1 (Foxo1) inhibits osteoblast production through Notch signaling. Foxo1 forms complexes with NICD and Mastermind to inhibit gene expression235,236 (Figs. 3, 4). As an illustration, Foxo1 inhibits nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) signaling in activated T cells. NFATc1 and NFATc2, in turn, promote the production of osteoblasts, bone formation, and osteoclasts235. Through its interaction with Foxo1, Notch directly and indirectly inhibits the generation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts236. GSK3 can phosphorylate NFATc, resulting in its nuclear export237. The co-localization of Notch2’s NICD with GSK3 in the nucleus can inhibit Wnt/β-catenin signaling235 and suppress osteoblast differentiation. The spalt-like transcription factor 4 (SALL4) can also regulate osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting Notch2’s ability to translocate into the nucleus238.

Epigenetic molecular processes dynamically modify both DNA and histone tails, influencing the spatial organization of chromatin and fine-tuning the outcome of Notch1 transcriptional response239. Although researchers have examined the interaction between histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and Notch in vitro and in Drosophila wing development, the precise role of this interaction in mammalian skeletal development and disorders remains uncertain240,241. In a murine model of osteosclerosis, HDAC1/2 has been identified as a contributor to the disease pathogenesis, which has been attributed to the conditionally cre-activated expression of the Notch1 intracellular domain in immature osteoblasts242. Significantly, targeted homozygous deletions of HDAC1/2 in osteoblasts result in partial alleviation of osteosclerotic phenotypes242. When HDAC1/2 was specifically deleted in osteoblasts of male and female mice, there was an absence of overt bone phenotypes, even in the absence of the Notch1 gain-of-function allele242. These findings provide evidence supporting the idea that HDAC1/2 contributes to the pathogenic signaling of Notch1 in the mammalian skeleton242.

Hippo signaling

Cell proliferation, apoptosis, and stem cell development rely heavily on the Hippo signaling cascade. When Hippo signaling is at an “on” state, YAP and TAZ undergo phosphorylation and are inhibited downstream243. YAP/TAZ are broken down in the cytoplasm, either through interaction with 14-3-3 proteins or through degradation mediated by the proteasome (Fig. 3)243. Yet, when Hippo signaling is inactive, YAP/TAZ translocates into the nucleus where they bind to the TEA domain transcription factor (TEAD), jointly regulating gene expression (Fig. 3)244. By initiating the downstream RhoGTPase-actomyosin signaling cascade, matrix metallopeptidase 14 (MMP14) can trigger β1-integrin activation and thereby promote YAP/TAZ nuclear transfer to regulate gene expression245.

YAP is an important component within Hippo signaling (Table 1). It regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis via cooperating with the Tead/Tef family and activating target genes in the Hippo signaling pathway246 (Fig. 3). In vitro experiments have exhibited that YAP can inhibit bone marrow MSC osteogenesis, subsequently reducing the rate of osteoblast differentiation247. According to previous research, YAP is a mediator of the Src/Yes tyrosine kinase pathway, which can interact with Runx2 to suppress Runx2 transcriptional activity to inhibit osteocalcin expression247.