Abstract

Background:

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy (CART) recipients who develop COVID-19 can have decreased overall survival, likely due to disease-inherent and therapy-related immunodeficiency. The availability of COVID-19 directed therapies and vaccines have improved COVID-19 related outcomes, but immunocompromised individuals remain vulnerable. Specifically, the effects of SARS-CoV-2 variant infections, including Omicron and its sublineages, particularly in transplant recipients, are yet to be defined. The aim of this study was to compare the impact of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infections in HCT/CART recipients with outcomes previously reported for ancestral SARS-CoV-2 infections early in the pandemic (March-June 2020).

Study Design:

Retrospective analysis adult HCT/CART recipients diagnosed with COVID-19 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York, between July 2021 and July 2022.

Results:

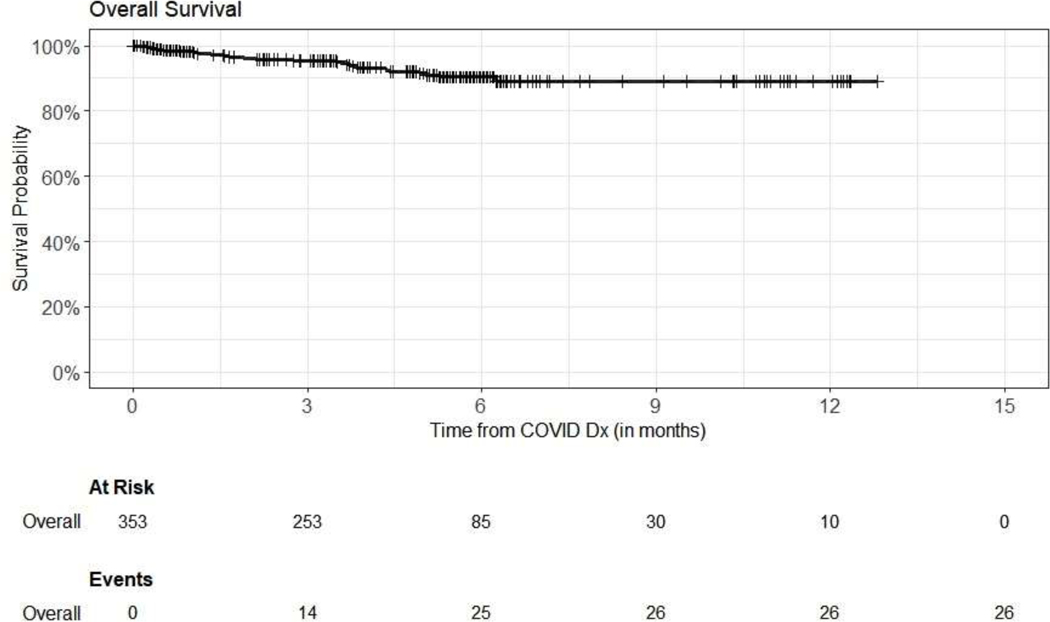

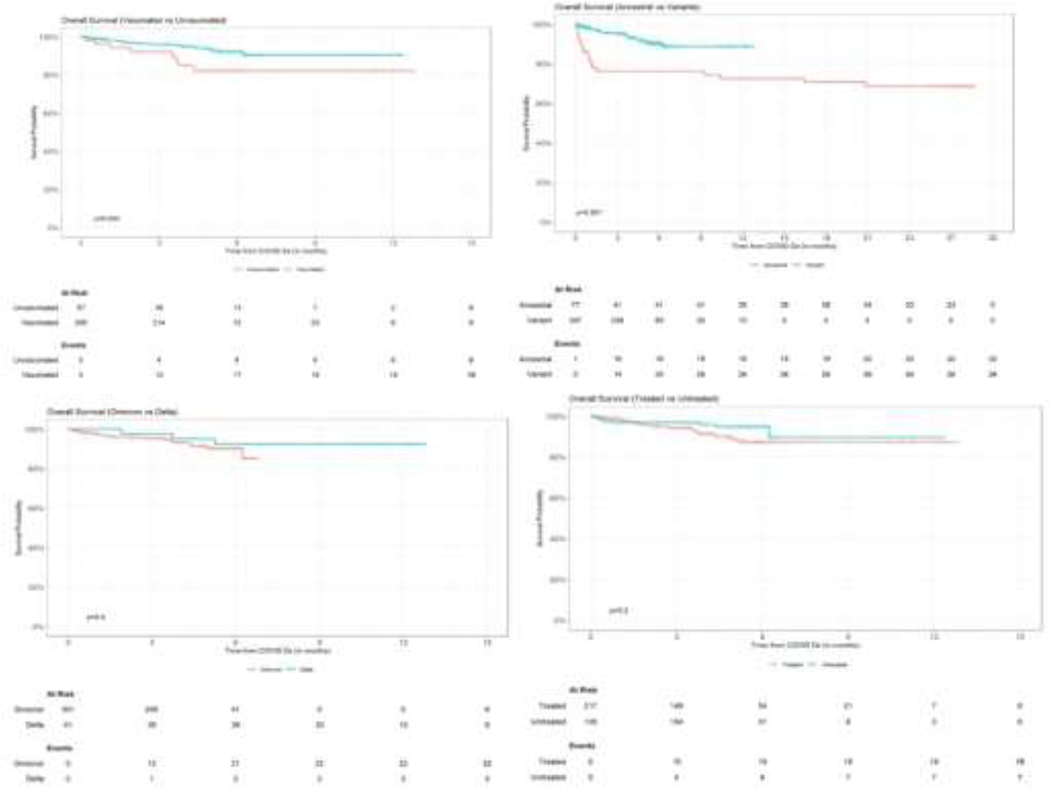

We identified 353 patients (172 auto, 49%; 152 allo, 43%; 29 CART, 8%) with a median time from HCT/CART to SARS-CoV-2 infection of 1010 days (IQR, 300 to 2046). Forty-one (12%) patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 during the delta wave and 312 (88%) patients during the Omicron wave. Risk factors associated with increased odds of COVID-19 related hospitalization were the presence of 2 or more comorbidities (OR, 4.9; 95% CI 2.4–10.7, p< 0.001), CART therapy compared to allogeneic HCT (OR 7.7; 95% CI 3.0–20.0, p<0.001), hypogammaglobulinemia (OR 2.71; 95% CI 1.06–6.40, p=0.027), and age at COVID-19 diagnosis (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.0–1.05, p= 0.04). In contrast, infection during Omicron variant BA5/BA4 dominant period compared to variant BA1 (OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.03–0.73, p =0.037), and more than 3 years from HCT/CART therapy to COVID-19 diagnosis, compared to early infection < 100 days (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.12–0.79, p=0.011) were associated with a decreased odds for hospitalization. The overall survival (OS) at 12 months from COVID-19 diagnosis was 89% (95% CI: 84–94%), with 6/26 deaths attributable to COVID-19. Patients with the ancestral strain of SAR-CoV-2 had a lower overall survival at 12 months, with 73% (95% CI: 62–84%) vs 89% (95% CI: 84–94%), (p<0.001) in the Omicron cohort. Specific COVID-19 treatment was administered in 62% of patients, and 84% were vaccinated with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccinated patients had significantly better OS than unvaccinated patients, being 90% (95% CI: 86–95%) vs 82% (95% CI: 72–94%) at 12 months, respectively (p=0.003). No significant difference in OS was observed in patients infected with the Omicron vs with Delta variant (p=0.4) or treated with specific COVID-19 treatments vs those not treated (p=0.2).

Conclusions:

We observed higher overall survival in HCT and CART recipients infected with the Omicron variants compared to the ancestral strain of SARS-CoV2. Use of COVID-19 antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, and vaccines may have contributed to improved outcomes.

Keywords: HCT and CAR-T patients, COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 therapy, vaccination, serologic response

Extended Abstract

Background:

HCT or CART therapy recipients who develop COVID-19 have decreased overall survival, likely due to disease-inherent and therapy-related immunodeficiency. The availability of COVID-19 therapies and vaccines have improved COVID-19 related outcomes, but immunocompromised individuals remain vulnerable. Specifically, the effects of SARS-CoV-2 variant infections, including Omicron and its sublineages, particularly in transplant recipients, are yet to be defined.

Objective:

To compare the impact of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infections in HCT/CART recipients with outcomes in previously reported ancestral SARS-CoV-2 infections during the early part of the pandemic (march-june 2020).

Study Design:

Retrospective analysis of 353 adult HCT/CART recipients diagnosed with COVID-19 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York, between July 2021 and July 2022.

Results:

We identified 353 patients (172 auto, 49%; 152 allo, 43%; 29 CART, 8%)) with a median time from HCT/CART to SARS-CoV2 infection of 1010 days (range, 300 to 2046). Risk factors associated with increased odds of COVID-19 related hospitalization were the presence of 2 or more comorbidities (OR, 4.9; 95% CI 2.4–10.7, p< 0.001), CART therapy compared to allogeneic HCT (OR 7.7; 95% CI 3.0–20.0,p <0.001), hypogammaglobulinemia (OR 2.71; 95% CI 1.06–6.40, p=0.027), and age at COVID diagnosis (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.0–1.05,p= 0.040). In contrast, infection during Omicron variant BA5/BA4 dominant period compared to variant BA1 (OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.03–0.73, p =0.037), and more than 3 years from HCT/CART therapy to COVID diagnosis, compared to early infection < 100 days (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.12–0.79, p=0.011) were associated with a decreased odds for hospitalization. The overall survival (OS) at 12 months from COVID diagnosis was 89% (95% CI: 84–94%), with 6/26 deaths attributable to COVID. The ancestral COVID cohort had a lower overall survival at 12 months, with 73% (95% CI: 62–84%) vs 89% (p<0.001) in the omicron variant cohort. Specific COVID-19 treatment was administered in 62% of patients and 84% were vaccinated with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccinated patients had significantly better OS than unvaccinated patients (90% (95% CI: 86–95%) vs 82% (95% CI: 72–94%) at 12 months, respectively , p=0.003). No significant difference in OS was observed in patients treated with specific COVID-19 treatments vs those not treated (p=0.2), nor in Omicron infections compared with delta ones (p=0.4).

Conclusions:

We observed higher overall survival in HCT and CART recipients infected with the Omicron variants compared to the ancestral strain of SARS-CoV2. Use of COVID-19 antivirals, monoclonal Ab and vaccines may have contributed to improved outcomes.

Introduction

Patients with active hematologic malignancies are at a higher risk of COVID-19 complications despite the availability of effective therapeutics and vaccines1–4. In particular, unfavorable outcomes have been reported in recipients of cellular therapies, including autologous (auto), allogeneic (allo) hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CART) compared to the general population 5–9.

The continuous evolution and spread of SARS-CoV-2 has led to the emergence of variants with enhanced immune evasion, transmissibility, and occasionally increased disease severity10–13. Since November 2021, variant B.1.1.529 (Omicron) rapidly replaced the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) globally14,15. The Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) possesses mutations associated with increased transmission and reduced protection from pre-existing immunity related to vaccination or infection, as well as the loss of activity of some monoclonal antibodies (mABs)16.

Although early data suggested that Omicron infections were less severe compared to previous variants of concern, the published experience among cellular therapy recipients is limited17. The infection rate with Omicron was much higher than in previous variants, and many cellular therapy recipients became infected during this wave. There is considerable uncertainty about the protection offered by vaccines and drugs in this group of patients, particularly against severe disease. In addition, the changing therapeutic landscape with the loss of efficacy of certain mABs was likely to influence the disease course after infection. For these reasons, SARS-CoV-2 variant-specific outcomes are essential to examine in cellular therapy recipients.

In the present study, we compared outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection with ancestral COVID-19 infection in HCT and CART recipients at the same institution in 2020.

Material and methods

Study design and outcomes

Between July 1, 2021 and July 31, 2022, consecutive patients who received allo, auto, or CART therapy were identified from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) institutional database and included if they had a positive nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) for SARS-CoV-2 either at MSKCC or reported a positive antigen or PCR test outside the institution after their cell infusion date.

The study population was compared with a historical cohort of 77 patients who received allo or auto at the same institution and were infected with SARS-C oV-2 during the first wave between March and May 202018.

The classification of SARS-C oV-2 variant was based on the prevalent sub-wave at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, as genotyping was not a standard clinical procedure.

Early COVID-19 treatment was administered 5 days or less after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

Reinfections were included and defined as clinical recurrence of symptoms compatible with COVID-19, accompanied by positive PCR test (cycle threshold [Ct] < 35), more than 90 days after the onset of the primary infection, supported by close-contact exposure or outbreak settings, and no evidence of another cause of infection.

The electronic medical record and institutional databases were abstracted for demographic information and medical history, including comorbidities (hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiac hear failure, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and HIV) and hematological treatment characteristics. Hypogammaglobulinemia was defined as a serum IgG level below 600 mg/dL. Laboratory and radiology information at the time of SARS-CoV-2 testing and subsequent admission (if admitted), as well as COVID-19 specific treatments, complications, and outcomes were collected from July 2021 through July 31, 2022. COVID-19 severity was defined as mild (no hospitalization required), moderate (hospitalization required for COVID-19 management regardless of oxygen requirement), and severe (intensive care unit [ICU] admission required or goals of care changed to comfort care rather than escalation to the ICU due to respiratory failure). COVID-19 was considered resolved once clinical symptoms were no longer present. Center for disease control and prevention (CDC) definition of post-acute COVID-19 or chronic infection was used, defined as > 4 weeks of viral detection with lower airway involvement and persistent or recurrent fever and dyspnea requiring rehospitalization19. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MSKCC.

Laboratory Methods

NPS sample collection and analysis was previously described by Shah et al7. SARS-N-acetylcysteine treatment was given on a clinical trial (NCT#04374461), while convalescent plasma (NCT#04338360) and remdesivir (NCT#04323761) were given through expanded access programs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, lab values, and disease characteristics. Overall survival from the date of COVID-19 diagnosis to death or last contact date was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methodology, and comparisons across groups were done using the logrank test. Univariable associations between clinical characteristics and COVID-19 severity were assessed using logistic regression. Both sets of univariable analyses were performed among patients with labs performed within 1 week of COVID-19 diagnosis. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Patients

From July 1, 2021, to July 31, 2022, 353 patients contracted with SARS-CoV-2. Our study population was categorized based on the prevalent variant and subvariant lineage at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, with 12% (41/353) of the patients infected with the Delta variant and 88% (312/353) with Omicron variant. The majority of the Omicron patients were diagnosed during the BA1 subwave (65%, n= 203/312), while 11% (33/312), 4% (12/312), and 17 (54/312) patients were diagnosed during the BA.2, BA2.12.1, and BA.5/BA.4 sub-waves, respectively. Characteristics and clinical presentation of the variant cohorts and the ancestral strain are described in Table 1. Among 353 patients, 172 (49%) received an auto HCT, 152 (43%) allo HCT, and 29 (8.2%) CART. The median age was 62 years (interquartile range [IQR], 51–69), and 58% were male. The median time from HCT/CART to SARS-CoV2 infection was 33.6 months (IQR, 10 – 68.2 months). Early infection within the first 100 days post-HCT/CART was diagnosed in 30 patients (8%). Twenty-nine patients (8%) had recurrent infections. The primary hematologic diagnoses were myeloid (35%) and lymphoid (30%) malignancies and plasma cell dyscrasias (35%). Myeloablative conditioning was used in 235 patients (67%), and in the allo recipients, donors were matched related (n=26, 17%), matched unrelated (n=88, 57%), umbilical cord blood (n=19, 12.5%), or haploidentical (n=9, 6%). CART recipients received axicabtagene ciloleucel (n=13), tisagenlecleucel (n=7), brexucabtagene autoleucel (n=1), JCAR017 (NCT#03310619, n=2), CD19/CD22-CART (NCT#05442515, n=2), idecabtagene vicleucel (n=4), and GPRC5D- CART (MCARH109, NCT#04555551n=1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical presentation of the Variant & Ancestral cohorts.

| Characteristic | Ancestor N = 77 | Variant N = 353 |

|---|---|---|

|

Cell Therapy Type Allo |

35 (45%) | 152 (43%) |

| Auto | 37 (48%) | 172 (49%) |

| CART | 5 (6.5%) | 29 (8.2%) |

| Age at COVID-19 Dx, years, median (IQR) | 62 (52, 68) | 62 (51, 69) |

|

Gender

Female |

28 (36%) | 148 (42%) |

| Male | 49 (64%) | 205 (58%) |

|

Race White |

45 (64%) | 284 (80%) |

| Black/ African American | 15 (21%) | 37 (10%) |

| Other | 6 (8.6%) | 5 (1.4%) |

| Asian/ Far East/ Indian Subcontinent | 4 (5.7%) | 27 (7.6%) |

| Unknown | 7 (9%) | - |

|

Diagnosis Plasma Cell Neoplasm |

29 (38%) | 124 (35%) |

| Acute/Chronic Leukemia | 21 (27%) | 91 (26%) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 20 (26%) | 95 (27%) |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 4 (5.2%) | 11 (3.1%) |

| Myeloproliferative Neoplasm | 2 (2.6%) | 8 (2.3%) |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 1 (1.3%) | 24 (6.8%) |

|

Smoking Status Never |

51 (66%) | 249 (71%) |

| Former | 25 (32%) | 95 (27%) |

| Current | 1 (1.3%) | 9 (2.5%) |

|

Vaping Status Never |

74 (96%) | 350 (99%) |

|

Comorbidity Total 0 |

34 (44%) | 148 (42%) |

| 1 | 26 (34%) | 102 (29%) |

| 2 | 14 (18%) | 60 (17%) |

| 3 | 3 (3.9%) | 31 (8.8%) |

| 4 | 0 | 10 (2.8%) |

| 5 | 0 | 2 (0.6%) |

| Time After Cell Therapy days (IQR) | 782 (354, 1,611) | 1,010 (300, 2,046) |

|

Donor Self |

42 (55%) | 172 (49%) |

| Unrelated | 22 (29%) | 88 (27%) |

| Related | 13 (17%) | 26 (17%) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 19 (12.5%) | |

| Haploidentical | 9 (6%) | |

| CART | 29 (8.2%) | |

|

Intensity Ablative |

50 (65%) | 235 (67%) |

| Reduced Intensity | 17 (22%) | 68 (19%) |

| Lympho- depleting | 5 (6.5%) | 29 (8.2%) |

| Nonablative | 5 (6.5%) | 21 (5.9%) |

|

GVHD Prophylaxis CI+MTX/MMF |

19 (26%) | 90 (58%) |

| CD 34+ selection | 9 (12%) | 26(17%) |

| PTCy | 7 (9.5%) | 20 (13%) |

| T-cell depletion | 0 | 13 (8.3%) |

| No | 0 | 5 (3.2%) |

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 14 (18%) | 27 (7.6%) |

| IgG Levels < 600 Treatment at time of COVID positive test |

20 (29%) | 22 (61 %) |

| Maintenance T reatment | 20 (27%) | 82 (23%) |

| Full Treatment | 11 (15%) | 61 (17%) |

| Symptoms at Time of COVID Positive Test | 71 (96%) | 320 (91%) |

| Cough | 50 (68%) | 247 (70%) |

| Fever | 45 (61 %) | 71 (20%) |

| Fatigue | 30 (41 %) | 103 (29%) |

| Sob | 23 (31 %) | 50 (14%) |

| Myalgias | 21 (28%) | 86 (24%) |

| Headache | 12 (16%) | 48 (14%) |

| Nausea Vomiting | 8 (11%) | 13 (3.7%) |

| Anosmia | 7 (9.5%) | 25 (7.1%) |

| Rhinorrhea | 6 (8.1%) | 242 (69%) |

| Confusion | 6 (8.1%) | 13 (3.7%) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (6.8%) | 29 (8.2%) |

| Diaphoresis | 3 (4.1%) | 51 (14%) |

| Weight Loss | 2 (2.7%) | 7 (2.0%) |

| Abdominal Pain | 1 (1.4%) | 28 (7.9%) |

Auto : autologous stem cell transplantation. Allo: allogeneic stem cell transplantation. GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; CI, calcineurin inhibitors; MTX, methotrexate; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; PTCy, post-transplant cyclophosphamide. SOB: shortness of breath

One-hundred and three (29%) patients had 2 or more comorbidities; hypertension (79%) and hyperlipidemia (40%) were most common (Table 1). The median BMI was 27 kg/m2 (IQR, 21 – 34 kg/m2). Most patients never smoked (71%). Of note, 40% of the patients were on active cancer therapy (maintenance or treatment) at the time of COVID-19 infection, with 66 patients receiving immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), 4 receiving bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKIs), and 6 receiving rituximab maintenance. Forty-six (30%) of the allo recipients were receiving systemic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) immunosuppressive treatment.

Most of the cohort (84%) was vaccinated with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, with 42% of patients having 1 booster before COVID-19 infection.

Regarding the status of the hematologic malignancy, 17% had a relapse or progression of the disease after allo, auto or CART prior to their COVID-19 diagnosis.

Symptoms and clinical course

Clinical presentation.

Overall, most of the patients (86%) in the entire cohort had mild disease compared to 48% in the ancestral cohort. Eight patients (2%) were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis and remained asymptomatic. The most frequent symptoms at Omicron variant COVID-19 onset were cough (70%), rhinorrhea (69%) and fatigue (29%), while in the ancestral cohort, the most frequent symptoms at presentation were cough (65%), fever (58%), fatigue (39%), and shortness of breath (30%). The majority (82%) of the patients did not have lab work or imaging done at the time of a positive test. Median time to symptom resolution was 14 days (range, 1–381 days). Fifty-one patients were hospitalized (14%) and median length of stay was 10 days (range, 2 – 410 days).

COVID-19 infection and directed treatments

Thirteen patients had received pre-exposure prophylaxis with tixagevimab-cilgavimab, with an additional 9 patients receiving it after their COVID-19 had resolved. Specific COVID-19 treatment was administered in 218 patients (62%) and included mABs in 137 patients (63%), sotrovimab being the most frequently used (n=55, 40%), nirmaltrevir/ritonavir (n=48, 16%), and remdesivir (n= 31, 14%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

COVID-19 treatments in the ancestral and Omicron variant.

| Received COVID-19 therapeutics |

Ancestor | Omicron |

|---|---|---|

| N = 36 | N = 218 | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 25 (69.5%) | 0 |

| Azithromycin | 19 (54%) | 18 (8.2%) |

| Methylprednisolone | 14 (40%) | 19 (8.7%) |

| Prednisone | 6 (8.3%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Chronic | 2 (17%) | 0 |

| Tocilizumab | 8 (23%) | 3 (1.5%) |

| Siltuximab | 1 (2.8%) | 0 |

| Anakinra | 1 (2.8%) | 0 |

| Convalescent Plasma | 12 (34%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Molnupiravir | 0 | 3 (1.5%) |

| Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir | 0 | 48 (22%) |

| Remdesivir IVIG | 0 5 (14%) | 31(13%) 1 (0.4%) |

| Jak-2 inhibitors (baracitinib) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Unknown mABs | 0 | 11 ( 5%) |

| Bamlanivimab Etesivimab | 0 | 3 (0.4%) |

| Bebtelovimab | 0 | 32 (14.6%) |

| Casirivimab Imdevimab | 0 | 25 (11.5%) |

| Sotrovimab | 0 | 55 (25%) |

| Bamlanivimab | 0 | 8 (3.6%) |

IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy, mABs: monoclonal antibodies

Risk factors associated with hospital admission

Of the 51 patients hospitalized in the entire cohort (=353), 29 patients (57%) showed pneumonitis or pneumonia on chest imaging, and 34 (67%) required supplemental oxygen (5/34 patients were on high flow oxygen). Four patients (8%) were already admitted at the time of COVID-19 infection and the remaining 18 patients were admitted for the following reasons: fever (n=7, 14 %), syncope (n=4,8%), flulike symptoms (n=12,6 %), septic embolia (n=1, 2%). Seven patients (2%) required admission to the ICU for oxygen supplementation. Eighteen patients had additional infections (9 bacteremia, 2 enterovirus, 2 urinary tract infection, 5 respiratory virus) at time of COVID-19 presentation. Forty-four patients (86%) received early COVID-19 treatment. Risk factors associated with an increased odds of admission were presence of 2 or more comorbidities, compared to none (odds ratio [OR], 4.9; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4–10.7, p< 0.001), CART therapy compared to allo (OR 7.7; 95% CI 3–20, p <0.001), hypogammaglobulinemia (OR 2.71; 95% CI 1.06–6.4, p=0.027), and age at COVID-19 diagnosis (OR 1.03; 95% CI 1.0–1.05, p=0.04). Omicron variant BA5/BA4 compared to variant BA1 (OR 0.21; 95% CI 0.03–0.73, p=0.037) and time from HCT/CART therapy to COVID-19 diagnosis > 36 months compared to < 100 days (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.12–0.79, p=0.011) were associated with a decreased odd of admission.

In comparison with Omicron variant patients, the ancestral cohort presented higher rates of admission (44% vs 14%), intubation (12% vs 2%), and adverse events such as deep vein thrombosis (2.7% vs 0.6%) or additional infection (32% vs 5.1%).

Vaccination status and serologic response

Regarding vaccination status, 84% (n= 295) of the Omicron cohort was vaccinated with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, with 42% of patients having 1 booster before COVID-19 infection. A total of 59% (n=208) of patients had serological testing in the first 72 hours from the disease onset to assess immunological response to prior vaccination. Of these, 53% (111/208) had a SARS-CoV-2 IgG (RBD) > 1000 IU/ml. For patients who had not received tixagevimab-cilgavimab, the SARS-CoV-2 IgG titer was >1000 IU/mL in 48%, 100%, 67%, 85%, 38%in those with the Delta and Omicron BA1, BA2, BA2.12.1, and BA4/5 variants, respectively.

Only 58 patients (16%) were not vaccinated for COVID-19: all of them had no serologic response at the time of COVID-19 infection, and 13 (22%) required admission. One patient developed chronic COVID-19 infection, and another died of progression of the underlying malignancy.

Chronic SARS CoV-2 infection and recurrence

Chronic infection was present in 29 (8.2%) patients with fatigue and respiratory symptoms as main symptoms. Five patients had a previous admission for COVID-19 and had a negative spike antibody titer before infection. Only 27% patients who had recurrent COVID-19 were administered monoclonal antibodies as specific COVID-19 treatment.

Only 6% of the patients with pre-exposure prophylaxis with tixagevimab-cilgavimab presented recurrent COVID-19 infection.

The majority of the patients with chronic infection had lymphoid malignancies (59%), and 7 patients (24%) underwent CART therapy. The median duration of viral shedding (positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR) in patients that were repeatedly checked was 8 weeks (range, 3.2 to 12 weeks).

Outcomes

The median follow up was 5.4 months (95% CI: 5.3–5.6 months), and 12-month overall survival was 89% (95% CI: 84–94%) for the Omicron variants cohort (Figure 1). There were 6 out of 23 deaths attributable to COVID-19 in the Omicron variants cohort. Other causes of death were progressive disease (n=15), sepsis (n=1) and hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD) (n=1). Twenty-nine patients (8%) had recurrent COVID-19 infection, and two of them died.

Figure 1.

Overall survival of the variants cohort

COVID-19 recurrence increased from 2.1% after 3 months from the first infection to 4.2% after the first year, as did the cumulative incidence of death (4.3% at month 3 to 9.2% at month 12). Comparing the Omicron cohort with the initial 77 HCT & CART patients infected with first wave SARS-CoV-2 at our institution from March 2020 to May 2020, overall survival (OS) at 12 months was 89% (95% CI: 84–94%) compared to 73% (95% CI: 62–84%) (p<0.001). In the Omicron cohort, vaccinated patients had significantly better OS than unvaccinated patients at 12 months: 90% (95% CI: 86–95%) vs 82% (95% CI: 72–94%) (p=0.003). No significant difference in OS was observed in patients treated with specific COVID-19 treatments vs not treated (p=0.2), nor in patients infected with the Omicron vs Delta variant (p=0.4) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival by (A) Vaccinated vs non-vaccinated, (B) Ancestral vs Omicron variant, (C) Omicron vs Delta variant and (D) Treated for COVID-19 vs not treated.

Discussion

Herein we present the largest cohort of highly vaccinated HCT/CART patients during the pandemic phase of Delta and Omicron variant COVID-19. In contrast to the high rates of severity and mortality reported in prior studies in HCT/CART patients during the early phase of the pandemic5,7,8,20,21,we show that, during the Omicron wave, rates of COVID-19 related hospitalization, ICU admission, and mortality were lower than previously reported with non-Omicron variants7,21–24. Despite the improved outcomes, those with advanced age, co-morbid conditions, and those undergoing CART treatment remain at a substantial risk for COVID-19 morbidity.

Interestingly, patients who received CART had a higher risk of admission. A possible explanation is that these patients have usually refractory disease and to a lesser extent they are not candidates for HCT because of comorbidities; in addition, they have a more prolonged immune recovery after cellular therapy compared to the auto patients25,26. We found the Omicron variant BA1.1 was a risk factor for admission, which could be related to an immunologic escape mechanism seen in the SARS-CoV-2 variants to the first generation vaccines27–29. On the other hand, active hematological (treatment or maintenance) or immunosuppressive treatment for GVHD at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis were not significant factors for disease severity.

While only 12% of the SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred in patients within 100 days of HCT/CART therapy, they were at increased risk for severe COVID-19 compared to COVID-19 infections occurring >1 year post HCT/CART therapy in agreement with prior studies7,30,31. Alternatively, rigorous infection control practices and patient avoidance of crowded places are likely reasons for these lower rates of COVID-19 in the early post-HCT/CART period and suggest that HCT/CART recipients follow a close vigilance protocol in order to prevent infection regardless of time since therapy. From these data, we can extrapolate that use of masks and hand hygiene should be continued in cellular therapy clinics and inpatient units regardless of COVID-19 vaccination status, and early intervention is suggested especially in patients with risk factors such as hypogammaglobulinemia or negative serologic response. Moreover surveillance strategies, such as regular swabs in inpatients, help reduce rates of nosocomial COVID-19 in times of high prevalence, avoiding the delay of cellular therapy, which has proven to convey in adverse outcome in these high risk patients32.

In our cohort, vaccination was the only factor significantly associated with better survival, signifying the importance of vaccines in our armamentarium against SARS-CoV-2 and potentially revaccination after cellular therapy going forward. The majority of the patients with at least two doses of mRNA vaccines where able to show some serologic response. These data support studies suggesting HCT patients are able to respond to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, with a response rate of 83% described in these patients after two doses of vaccines, although with a lower antibody responses compared to the healthy controls33–36. Regarding CART, even though prolonged B-cell depletion, together with hypogammaglobulinemia and cytopenias, can further diminish immune responses to vaccines, our study reinforces published data on enhancement of humoral and cellular response (11–76%) to SARS-CoV-2 in patients after CART after at least 2 doses of vaccine, and similar responses to healthy controls after the third dose37–39. Nonetheless, limited immunogenicity and variability on RBD cut-off, support the importance of re-vaccination in patients undergoing CART and vaccination with more than 2 doses in all CART patients39,40. Moreover, in the first reports of cancer patients infected with the Omicron variant, unvaccinated patients had similar rates of fatality, hospitalization, and complications from COVID-19 as those diagnosed during the alpha-delta phase (before December 2021)41,42. Time of vaccination is equally important: a large prospective analysis supports initiation of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination three months after HCT, where 57% of the patients produced neutralizing antibody43. Humoral response rates were higher (75%) among individuals vaccinated with 2 doses >12 months after receiving CART, but T-cell responses (57%) were similar. Even though the quantitative serologic response cutoff for protection is not well defined, the RBD level maybe useful in the management of HCT/CART patients who fail to develop a strong humoral response to the virus and suggest need for intervention with available therapeutics44 or additional doses of vaccine.

Regarding COVID-19 specific therapy, our study highlights the shift from the extensive use of corticosteroids and antibiotics in the first wave to early treatment with specific monoclonal antibodies and antivirals of outpatients with mild symptoms in the pandemic phase45,46. We could not demonstrate impact of specific COVID-19 treatments in survival, likely due to overall improved survival and risk-based use of therapies. Nevertheless duration and severity of symptoms were lower than previously described in the first wave and were similar to reports in solid organ recipients with early mABs treatment during the Omicron phase47. Moreover, preliminary studies about pre-exposure prophylaxis with tixagevimab/cilgavimab in allo-HCT patients48 demonstrate it prevents severe and potentially lethal forms of COVID-19 in this population. The low rates of patients with prior tixagevimab/cilgavimab in our series potentially support this as many patients received prophylaxis at our center during this time frame.

The incidence of chronic SARS-CoV-2 infection is higher than described in the general population (3.5%)47, and it seems to be related to absence of serologic response and severity of COVID-19 at presentation. Similarly, rates of recurrence are higher and are a predictor of mortality. Our cohort shows delayed PCR clearance49, which is consistent with multiple reports where prolonged viral shedding and low circulating B cell counts have been observed in HCT recipients21,50,51. HCT/CART recipients have profound immune dysregulation and may shed viable SARS-CoV-2 for at least 2 months after symptom onset, consistent with persistent infection21,36. It is crucial to optimize the treatment of these patients, as the virus exhibits characteristics of a chronic infection rather than an acute one. To achieve this, clinical trials are needed in order to find new therapies or combination treatments to achieve the remission of the infection. The ultimate goal is to enable these individuals to safely undergo the vital treatments they require without delay.

We recognize limitations of our study inherent to the retrospective design. Patients were included based on testing at our center or patient report to us. Therefore, we may have missed patients who were seen by local providers and not reported or patients who did not report symptoms. It is also possible that treatments administered by outside providers were not captured. Biochemical parameters were not checked as frequently in the non-hospitalized patients, and therefore these data are an incomplete picture of patients with milder disease. COVID-19 severity and mortality between the Historical cohort and the later study population may be influenced by availability and changes in the treatment of COVID-19, improved care of patients with COVID-19, earlier detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR and later at home antigen assays, whereas tests were not readily available in the beginning of the pandemic. While later SARS-CoV-2 variants may in fact be less virulent, these factors may be confounding our outcomes results. Only univariable analysis was done for risk factors for admission and therefore the study is vulnerable to confounding factors which makes it difficult to isolate the true effects of the variables being investigated.

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated that vaccination, the different biology of COVID-19 variants, and novel COVID-19 treatments significantly improved rates of mortality and severity in recipients of cellular therapies. The goal therefore remains to revaccinate patients post cellular therapy and to continue development of prophylactic and treatment monoclonal antibodies to protect patients as newer variants arise.

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of risk factors for admission.

| Characteristic | Required Admission, N = 511 | OR2 | 95% CI2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cell Therapy Type

Allo |

14 (9.4%) | — | — | |

| Auto | 25 (15%) | 1.65 | 0.83, 3.39 | 0.2 |

| CART | 12 (44%) | 7.71 | 3.02, 20.0 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Age at COVID-19 Diagnosis, years, median (IQR) | 64 (57, 71) | 1.03 | 1.00, 1.05 | 0.040 |

|

| ||||

|

Variant BA1 |

32 (16%) | — | — | |

| BA2 | 5 (15%) | 0.94 | 0.30, 2.45 | >0.9 |

| BA2.12.1 | 0 (0%) | NE3 | 3 | >0.9 |

| BA5/BA4 | 2 (3.8%) | 0.21 | 0.03, 0.73 | 0.037 |

| DELTA | 12 (24%) | 1.71 | 0.78, 3.57 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||

|

Gender Male |

28 (14%) | — | — | |

| Female | 23 (16%) | 1.19 | 0.65, 2.16 | 0.6 |

|

| ||||

|

Race White |

43 (15%) | — | — | |

| Asian/ Far East/ Indian | 6 (22%) | 1.56 | 0.55, 3.89 | 0.4 |

| Black/ African American | 1 (2.7%) | 0.15 | 0.01, 0.73 | 0.066 |

| Other | 1 (20%) | 1.37 | 0.07, 9.51 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||

|

Hematologic disease Acute/Chronic Leukemia |

11 (12%) | — | — | |

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 0 (0%) | NE | >0.9 | |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 1 (4.3%) | 0.33 | 0.02, 1.82 | 0.3 |

| Myeloproliferative Neoplasm | 1 (12%) | 1.03 | 0.05, 6.60 | >0.9 |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 21 (23%) | 2.09 | 0.96, 4.79 | 0.069 |

| Plasma Cell Neoplasm | 17 (14%) | 1.16 | 0.52, 2.69 | 0.7 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking Status | 15 (16%) | 1.26 | 0.63, 2.41 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| antiCD20 Exposure | 0 (0%) | NE | >0.9 | |

|

| ||||

| ITK Exposure | 0 (0%) | NE | >0.9 | |

|

| ||||

| GVHD Immunosuprresants | 6 (9.7%) | 0.57 | 0.21, 1.31 | 0.2 |

|

| ||||

| Steroid | 16 (22%) | 1.92 | 0.97, 3.66 | 0.053 |

|

| ||||

| Hypogammaglobulinemia | 8 (30%) | 2.71 | 1.06, 6.40 | 0.027 |

|

| ||||

|

Comorbidity Total

0 |

12 (8.2%) | — | — | |

| 1 | 8 (8.1%) | 0.99 | 0.37, 2.49 | >0.9 |

| 2+ | 31 (31%) | 4.98 | 2.47, 10.7 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

|

Time from HCT/CART to COVID-19, days (%) ≤ 100 |

9 (30%) | — | — | |

| 100 – 180 | 3 (12%) | 0.33 | 0.07, 1.30 | 0.13 |

| 181 – 365 | 7 (16%) | 0.45 | 0.14, 1.39 | 0.2 |

| 366 – 1095 | 13 (15%) | 0.42 | 0.16, 1.13 | 0.079 |

| ≥ 1096 | 19 (12%) | 0.31 | 0.12, 0.79 | 0.011 |

|

| ||||

| tixagevimab-cilgavimab exposure | 2 (9.5%) | 0.60 | 0.09, 2.14 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

| Vaccinated | 40 (14%) | 0.67 | 0.33, 1.46 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||

| Full/Maintenance treatment | 22 (16%) | 1.19 | 0.65, 2.17 | 0.6 |

n (%); Median (IQR)

OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval

(NE) Non-Estimable; 0 patients required hospital admission

Auto: autologous stem cell transplantation. Allo: allogeneic stem cell transplantation. ITK: tyrosine-kinase inhibitors, GVHD: graft versus host disease.

Highlights.

Despite the improved outcomes in HCT/CART patients with Omicron variant COVID-19, those with advanced age, co-morbid conditions, and those undergoing CAR-T treatment remain at a substantial risk for COVID-19 morbidity

Vaccination is the only significant factor associated with enhanced survival in those patients

The impact of specific COVID-19 treatments in survival could not be demonstrated, nevertheless duration and severity of symptoms were lower in treated patients

Incidence of chronic COVID-19 infection is higher than described in the general population, likely related to absence of serologic response and severity of COVID-19 at presentation

Rates of recurrence are higher and are a predictor of mortality

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health award number P01 CA23766 and National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant P30 CA008748. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

MAP reports honoraria from Adicet, Allogene, Allovir, Caribou Biosciences, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Equilium, Exevir, ImmPACT Bio, Incyte, Karyopharm, Kite/Gilead, Merck, Miltenyi Biotec, MorphoSys, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, Omeros, OrcaBio, Syncopation, VectivBio AG, and Vor Biopharma. He serves on DSMBs for Cidara Therapeutics, Medigene, and Sellas Life Sciences, and the scientific advisory board of NexImmune. He has ownership interests in NexImmune, Omeros and OrcaBio. He has received institutional research support for clinical trials from Allogene, Incyte, Kite/Gilead, Miltenyi Biotec, Nektar Therapeutics, and Novartis.

GLS has received research funding from Janssen, Amgen, BMS, and Beyond Spring. DSMB for ArcellX

YJL has served as an investigator for Karius, AiCuris, and Scynexis and has received research grant support from Merck & Co Inc.

MK serves on Consultant Regeneron and MJH life sciences

SS has received research funding from Merck.

SDW receives research support from the MSK Leukemia SPORE Career Enhancement Program (NIH/NCI P50 CA254838–01) and the MSK Gerstner Physician Scholar program.

IP has received research funding from Merck and an honorarium from Precisionheor, and he serves as a member of Data and Safety Monitoring Board for ExCellThera.

SG receives research funding from Miltenyi Biotec, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Celgene Corp., Amgen Inc., Sanofi, Johnson and Johnson, Inc., Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and is on the Advisory Boards for: Kite Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Celgene Corp., Sanofi, Novartis, Johnson and Johnson, Inc., Amgen Inc., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

GP received research funding from MSD.

RT serves as BMT CTN Medical Monitor.

Footnotes

The rest of the authors declare no COIs.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shah V, Ko Ko T, Zuckerman M, Vidler J, Sharif S, Mehra V et al. Poor outcome and prolonged persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 patients with haematological malignancies; King’s College Hospital experience. Br J Haematol 2020. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martín-Moro F, Marquet J, Piris M, Michael BM, Sáez AJ, Corona M et al. Survival study of hospitalized patients with concurrent Covid-19 and haematological malignancies. British Journal of Haematology; n/a. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He W, Chen L, Chen L, Yuan G, Fang Y, Chen W et al. COVID-19 in persons with haematological cancers. Leukemia 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0836-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aries JA, Davies JK, Auer RL, Hallam SL, Montoto S, Smith M et al. Clinical Outcome of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Haemato-oncology Patients. Br J Haematol 2020. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busca A, Salmanton-García J, Marchesi F, Farina F, Seval GC, Van Doesum J et al. Outcome of COVID-19 in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: Results from the EPICOVIDEHA registry. Front Immunol 2023; 14: 1125030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maurer K, Saucier A, Kim HT, Acharya U, Mo CC, Porter J et al. COVID-19 and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and immune effector cell therapy: a US cancer center experience. Blood Advances 2021; 5: 861–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah GL, DeWolf S, Lee YJ, Tamari R, Dahi PB, Lavery JA et al. Favorable outcomes of COVID-19 in recipients of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2020; 130: 6656–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A, Bhatt NS, Martin ASt, Abid MB, Bloomquist J, Chemaly RF et al. COVID-19 in Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients: A CIBMTR Study. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2021; 27: S4–S5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeWolf S, Laracy JC, Perales M-A, Kamboj M, van den Brink MRM, Vardhana S. SARS-CoV-2 in immunocompromised individuals. Immunity 2022; 55: 1779–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies NG, Abbott S, Barnard RC, Jarvis CI, Kucharski AJ, Munday JD et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 2021; 372: eabg3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mlcochova P, Kemp SA, Dhar MS, Papa G, Meng B, Ferreira IATM et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature 2021; 599: 114–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito A, Tamura T, Zahradnik J, Deguchi S, Tabata K, Kimura I et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.75. Microbiology, 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.08.07.503115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang P, Casner RG, Nair MS, Wang M, Yu J, Cerutti G et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variant P.1 to antibody neutralization. Cell Host & Microbe 2021; 29: 747–751.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishiura H, Ito K, Anzai A, Kobayashi T, Piantham C, Rodríguez-Morales AJ. Relative Reproduction Number of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) Compared with Delta Variant in South Africa. JCM 2021; 11: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Ichikawa T, Suzuki S, Tanino Y, Kakinoki Y. Clinical characteristics of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 omicron variant compared with the delta variant: a retrospective case-control study of 318 outpatients from a single sight institute in Japan. PeerJ 2022; 10: e13762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox M, Peacock TP, Harvey WT, Hughes J, Wright DW, COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant evasion of monoclonal antibodies based on in vitro studies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023; 21: 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Letailleur V, Le Bourgeois A, Guillaume T, Peterlin P, Garnier A, Jullien M et al. Incidence and Severity of COVID-19 Infections in a Cohort of 211 Allotransplanted Patients after One or Two Boosters during the Omicron Wave in France. Blood 2022; 140: 7660–7661. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah GL, DeWolf S, Lee YJ, Tamari R, Dahi PB, Lavery JA et al. Favorable outcomes of COVID-19 in recipients of hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 6656–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/facts-heets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed 16 May2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma A, Bhatt NS, St Martin A, Abid MB, Bloomquist J, Chemaly RF et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation recipients: an observational cohort study. The Lancet Haematology 2021; 8: e185–e193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mushtaq MU, Shahzad M, Chaudhary SG, Luder M, Ahmed N, Abdelhakim H et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy Recipients. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy 2021; 27: 796.e1–796.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piñana JL, Martino R, García-García I, Parody R, Morales MD, Benzo G et al. Risk factors and outcome of COVID-19 in patients with hematological malignancies. Exp Hematol Oncol 2020; 9: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ljungman P, de la Camara R, Mikulska M, Tridello G, Aguado B, Zahrani MA et al. COVID-19 and stem cell transplantation; results from an EBMT and GETH multicenter prospective survey. Leukemia 2021; 35: 2885–2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma A, Kosuri S, Ustun C, Ibrahim U, Moreira J, Bishop MR et al. COVID-19 infection in hematopoietic cell transplantation: age, time from transplant and steroids matter. Leukemia 2020; 34: 2809–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kampouri E, Walti CS, Gauthier J, Hill JA. Managing hypogammaglobulinemia in patients treated with CAR-T-cell therapy: key points for clinicians. Expert Review of Hematology 2022; 15: 305–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strati Paolo, Varma Ankur, Adkins Sherry, Nastoupil Loretta J., Westin Jason, Hagemeister Fredrick B. et al. Hematopoietic recovery and immune reconstitution after axicabtagene ciloleucel in patients with large B-cell lymphoma. haematol 2020; 106: 2667–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aggarwal A, Akerman A, Milogiannakis V, Silva MR, Walker G, Stella AO et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5: Evolving tropism and evasion of potent humoral responses and resistance to clinical immunotherapeutics relative to viral variants of concern. EBioMedicine 2022; 84: 104270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha LB, Foster C, Rawlinson W, Tedla N, Bull RA. Evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants BA.1 to BA.5: Implications for immune escape and transmission. Rev Med Virol 2022; 32: e2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau JJ, Cheng SMS, Leung K, Lee CK, Hachim A, Tsang LCH et al. Real-world COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron BA.2 variant in a SARS-CoV-2 infection-naive population. Nat Med 2023; 29: 348–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanellopoulos A, Ahmed MZ, Kishore B, Lovell R, Horgan C, Paneesha S et al. COVID-19 in bone marrow transplant recipients: reflecting on a single centre experience. Br J Haematol 2020; 190. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coll E, Fernández-Ruiz M, Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Martínez-Fernández JR, Crespo M, Gayoso J et al. COVID-19 in transplant recipients: The Spanish experience. American Journal of Transplantation 2021; 21: 1825–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawas MT, Shah GL, Feldman DR, Ruiz JD, Robilotti EV, Aslam AA et al. Cellular Therapy During COVID-19: Lessons Learned and Preparing for Subsequent Waves. Transplant Cell Ther 2021; 27: 438.e1–438.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piñana JL, López-Corral L, Martino R, Montoro J, Vazquez L, Pérez A et al. SARS-CoV-2-reactive antibody detection after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: Prospective survey from the Spanish Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cell Therapy Group. Am J Hematol 2022; 97: 30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang A, Cicin-Sain C, Pasin C, Epp S, Audigé A, Müller NJ et al. Antibody Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Patients following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Transplant Cell Ther 2022; 28: 214.e1–214.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamari R, Politikos I, Knorr DA, Vardhana SA, Young JC, Marcello LT et al. Predictors of Humoral Response to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and CAR T-cell Therapy. Blood Cancer Discov 2021; 2: 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wudhikarn K, Perales M-A. Infectious complications, immune reconstitution, and infection prophylaxis after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant 2022; 57: 1477–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiedmeier-Nutor JE, Iqbal M, Rosenthal AC, Bezerra ED, Garcia-Robledo JE, Bansal R et al. Response to COVID-19 Vaccination Post-CAR T Therapy in Patients With Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2023; : S2152–2650(23)00076–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Levels Measured by the AdviseDx SARS-CoV-2 Assay Are Concordant with Previously Available Serologic Assays but Are Not Fully Predictive of Sterilizing Immunity | Journal of Clinical Microbiology. https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/JCM.00989-21 (accessed 17 May2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez MA, Bhatti AM, Fitzpatrick K, Boonyaratanakornkit J, Huang M-L, Campbell VL et al. Humoral and cellular responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines before and after chimeric antigen receptor–modified T-cell therapy. Blood Advances 2023; 7: 1849–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill JA, Seo SK. How I prevent infections in patients receiving CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells for B-cell malignancies. Blood 2020; 136: 925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pinato DJ, Aguilar-Company J, Ferrante D, Hanbury G, Bower M, Salazar R et al. Outcomes of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant outbreak among vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with cancer in Europe: results from the retrospective, multicentre, OnCovid registry study. Lancet Oncol 2022; 23: 865–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortellini A, Tabernero J, Mukherjee U, Salazar R, Sureda A, Maluquer C et al. SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529)-related COVID-19 sequelae in vaccinated and unvaccinated patients with cancer: results from the OnCovid registry. Lancet Oncol 2023; : S1470–2045(23)00056–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill JA, Martens MJ, Young J-AH, Bhavsar K, Kou J, Chen M et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the first year after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant: a prospective, multicentre, observational study. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 59: 101983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khan QJ, Bivona CR, Martin GA, Zhang J, Liu B, He J et al. Evaluation of the Durability of the Immune Humoral Response to COVID-19 Vaccines in Patients With Cancer Undergoing Treatment or Who Received a Stem Cell Transplant. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8: 1053–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan J, Steiger SN, Kodama R, Fender J, Tan C, Laracy J et al. Predictors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Hospitalization After Sotrovimab in Patients With Hematologic Malignancy During the BA.1 Omicron Surge. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: 1476–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuver R, Shah GL, Korde NS, Roeker LE, Mato AR, Batlevi CL et al. Activity of AZD7442 (tixagevimab-cilgavimab) against Omicron SARS-CoV-2 in patients with hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell 2022; 40: 590–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solera JT, Árbol BG, Alshahrani A, Bahinskaya I, Marks N, Humar A et al. Impact of Vaccination and Early Monoclonal Antibody Therapy on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outcomes in Organ Transplant Recipients During the Omicron Wave. Clin Infect Dis 2022; : ciac324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jondreville L, D’Aveni M, Labussière-Wallet H, Le Bourgeois A, Villate A, Berceanu A et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis with tixagevimab/cilgavimab (AZD7442) prevents severe SARS-CoV-2 infection in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation during the Omicron wave: a multicentric retrospective study of SFGM-TC. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2022; 15: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Babady NE, Cohen B, McClure T, Chow K, Caldararo M, Jani K et al. Variable duration of viral shedding in cancer patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022; 43: 1413–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cesaro S, Ljungman P, Mikulska M, Hirsch HH, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Cordonnier C et al. Recommendations for the management of COVID-19 in patients with haematological malignancies or haematopoietic cell transplantation, from the 2021 European Conference on Infections in Leukaemia (ECIL 9). Leukemia 2022; 36: 1467–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aydillo T, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Aslam S, van de Guchte A, Khan Z, Obla A et al. Shedding of Viable SARS-CoV-2 after Immunosuppressive Therapy for Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2586–2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]