Abstract

Background

Women at middle age are puzzled by a series of menopausal disturbances, can be distressing and considerably affect the personal, social and work lives. We aim to estimate the global prevalence of nineteen menopausal symptoms among middle-aged women by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

Comprehensive search was performed in multiple databases from January, 2000 to March, 2023 for relevant studies. Random-effect model with double-arcsine transformation was used for data analysis.

Results

A total of 321 studies comprised of 482,067 middle-aged women were included for further analysis. We found varied prevalence of menopausal symptoms, with the highest prevalence of joint and muscular discomfort (65.43%, 95% CI 62.51–68.29) and lowest of formication (20.5%, 95% CI 13.44–28.60). Notably, South America shared dramatically high prevalence in a sort of menopausal symptoms including depression and urogenital symptoms. Besides, countries with high incomes (49.72%) had a significantly lower prevalence of hot flashes than those with low (65.93%), lower-middle (54.17%), and upper-middle (54.72%, p < 0.01), while personal factors, such as menopausal stage, had an influence on most menopausal symptoms, particularly in vaginal dryness. Prevalence of vagina dryness in postmenopausal women (44.81%) was 2-fold higher than in premenopausal women (21.16%, p < 0.01). Furthermore, a remarkable distinction was observed between body mass index (BMI) and prevalence of sleep problems, depression, anxiety and urinary problems.

Conclusion

The prevalence of menopausal symptoms affected by both social and personal factors which calls for attention from general public.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-19280-5.

Keywords: Menopause, Prevalence, Middle-aged women, Somatic, Psychological, Urogenital

Background

Female hormones play a pivotal role in women’s life. Their rise initiate puberty, makes motherhood possible, and ensure cardioprotective functions and bone health [1, 2]. However, regardless of their cultural background and medical histories, nearly all women start to have physical, psychological and emotional disturbances after mid-forties [3]. Those turmoil coincide with the loss of ovarian reproductive function, is an inevitable component of ageing and happens at a time in a woman’s life when she is frequently actively involved in raising her family or handling a full-time job, during which time she might also have the responsibility of caring for ageing parents [4]. The majority of women affected by marked fluctuations in levels of sex hormones are often puzzled by the remarkable changes in mood, sleep patterns, and memory, as well as the onset of vasomotor and urogenital symptoms [5]. These menopause-related symptoms, which actually begin before menstrual cycles ends and prevalent in middle-aged women, can be very distressing and considerably affect the personal, social and work lives of women [5, 6].

Nowadays, the relationship between psychosomatic symptoms and the women’s overall well-being is currently the focus of research across many fields, going from medical to social sciences. While epidemiological studies have provided a similar picture of menopausal symptoms trajectories in all geographical regions and ethnicities, there are significant differences in the prevalence of certain symptoms. For instance, vasomotor symptoms (VMS), characterized by hot flashes and/or night sweats, are the main symptoms of menopause. The US-based Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) reports that the prevalence of VMS is 50–82% among US women who go through natural menopause [7]. A radically lower prevalence, ranging from 36 to 50% in Norther America to 22–63% in Asia [8]. Likewise, disparities in the prevalence of depression in middle-aged women across different countries were noted. According to an Indian study, the prevalence of depression was approximately 40.0%, which is comparable to Brazil’s prevalence of 36.8% [9, 10]. Besides, depression is somewhat less common in the Chinese population with an estimate of 25.99% [11]. These differences might be explained by the fact that most cross-cultural studies only involved small numbers of participants and have mostly been restricted to one country or continent.

Over the past decade, data from epidemiological studies involving middle-aged women have been made available for investigators in the field of menopause. However, the current understanding of the epidemiology of menopause-related symptoms is based mostly on a few geographic surveys and very little national evidence, without rigorous systemic data that explores not only the general prevalence of menopause-related symptoms, but also risk factors associated with them. Besides, there is a paucity of articles to describe the global prevalence of menopausal symptoms from multiple domains, and most studies are limited to a certain symptom. For example, a meta-analysis of 10 studies conducted in Indian population showed that the prevalence of depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women was 42.47% [12] and another meta-analysis involving 41 studies found that the overall prevalence of sleep disorders among postmenopausal women was 51.6% [13]. Therefore, we performed current study aim to close this void by presenting an updated global epidemiology of nineteen menopause-related symptoms, providing subgroup analysis across geographic regions and synthesizing critical risk factors.

Methods

We carried out a meta-analysis of all published studies on the prevalence of menopausal symptoms from January, 2000 through March, 2023 in accordance with the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). A total of nineteen menopause-related symptoms included in this study were classified into four domains: somatic symptoms (hot flashes, sleep problems, heart discomfort, headache, and joint and muscular discomfort), psychological symptoms (physical and mental exhaustion, depression, anxiety, irritability and mood swings), urogenital symptoms (sexual problems, vaginal dryness, and urinary problems) and others (forgetfulness, difficult concentration, formication, change in the appearance, texture, or tone of skin, increased facial hair, and drying skin). The study protocol was pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023486818).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted in Medline, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases using the relevant medical subject heading search terms and keywords. Full details of the search strategy for each database can be found in the Supplementary method. Datasets from studies that fulfilled the following criteria were deemed eligible: (a) P: participants were middle-aged women in premenopausal, perimenopausal or postmenopausal stages according to the WHO’s classification; (b) O: Adequate information for the pooled estimate of menopausal symptoms prevalence; (c) O: prevalence of menopausal symptoms was determined using standardized instruments, self-reported questionnaires, face-to-face, telephone or mail interviews; (d) S: Cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control study designs; (e) studies in English; (f) studies published between 2000 and 2023. Studies were excluded if (a) P: participants seeking treatment for menopausal symptoms in hospitals; (b) S: studies were conference paper, abstract, letters, review or meta-analysis; (c) study size less than 50.

Pre-determined decision rules were used to screen studies. After removal of duplicate articles, two reviewers (Y.F and J.L) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all articles identified by the literature search, with 10% of studies randomly reviewed by another investigator (K.L). Then the investigators reviewed (Y.F and K.Z) the complete texts of theoretically qualifying papers, with any inconsistencies settled through agreement or by another reviewer (Z.L). Consensus was found in all cases and agreement was reached. More details refer to included articles are presented in the Supplementary materials.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The methodological quality of epidemiological studies was assessed using a scale developed by Parker et al. [14]. with the following items: sampling methods; response rate; the definition and representative of targeted population and the validation of assessment instrument.

We extracted the following variables from included literature: the first author of the study, country, continent, income level of the country assessed by the World Bank, the status of country development, year of publication, study quality, diagnosis criteria, sample size and prevalence proportion. Moreover, a comparison was made of the prevalence of menopausal symptoms classified by menopausal status (premenopause, perimenopause or postmenopause), marital status (married or single/divorced/widowed), educational level (less than 12 years or more than 12 years), residence (urban or rural), physical activity (regular or irregular), employment (unemployed or employment), BMI (underweight, normal weight, overweight or obesity), current smoking (YES/NO), alcohol use (YES/NO). Menopausal status was defined in accordance to the WHO’s classification. To elucidate this distribution, women with regular menstrual bleeding during the last year were classified as premenopause, those with irregular bleeding during the last 12 months as perimenopause. Finally, women were classified as postmenopaused, if they had no menstrual bleeding from 1 year and above. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the actual weight, in kilograms, divided by height, in meters squared, relying on the anthropometric inputs (height, weight) measured respectively by a stadiometer and a digital scale, by the research team, the day of the recruitment. It was then categorized according to the WHO cut-off points: underweight if less than 18.5, normal if between 18.5 and 24.9, overweight if between 25 and 29.9 and obese from 30 and above [15]. When multiple articles of the same study population were identified, we included them if the data differed by time on prevalence of menopausal symptoms. Whenever important information was missing, we contacted corresponding authors.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using R software (V4.0.0) with “Meta” and “Metafor” statistical packages. Heterogeneity across included studies was measured with I2. Estimates with I2 of 50% or greater was considered as moderate heterogeneity. The double-arcsine transformation was used for variance stabilization of proportions, and pooled estimates of the prevalence of menopausal symptoms in all studies were calculated using the random-effects approach, due to the heterogeneity. The meta-prop command was used to generate forest plots of pooled prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the Wilson score method. Subgroup analyses were conducted and defined by geographical location, income level of the country, the status of country development, year of publication, study quality, diagnosis criteria, and sample size. Social characteristics of participants were compared with the prevalence of each menopausal symptoms to determine the pooled estimates of risk factors. To reduce the probability of committing a type I error due to the high number of subgroup comparisons, Bonferroni correction was used. The p value < 0.05 was considered as significant difference. For more details, the R code of this study has been added in the supplementary material.

Certainty of evidence

The quality of pooled evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

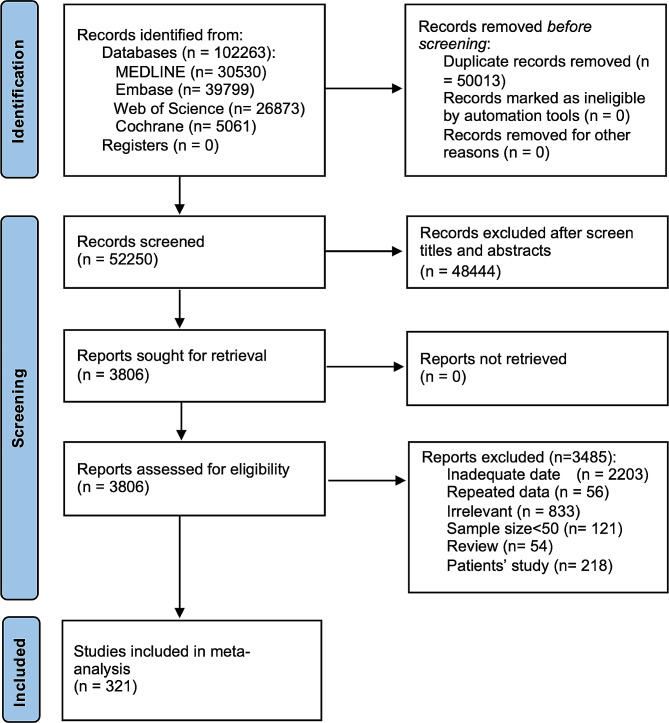

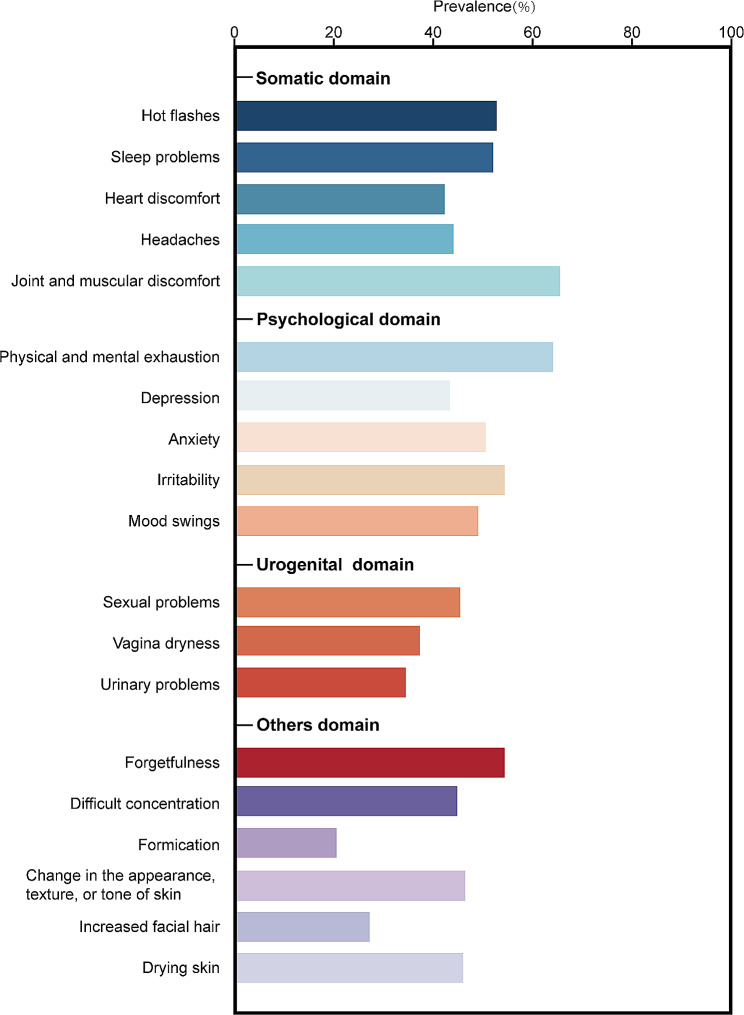

Our search strategy identified 102,263 records, of which 52,250 records were retained after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts were screened, resulting in the exclusion of 48,444 ineligible records. Following an eligibility assessment of the full texts of the remaining 3,806 records, 3,485 were deemed ineligible. Overall, 321 eligible studies with data reporting menopausal symptoms involving 482,067 middle-aged women met our inclusion criteria and included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). Hot flashes were the symptom with the most articles featured which including 265 articles comprising 349,608 middle-aged females, formation had the fewest, with 16 articles containing 52,195 individuals. The majority of included studies had a cross-sectional design. The quality assessment scores of included studies are displayed in Supplementary Table 1. Furthermore, the pooled prevalence of nineteen symptoms is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram

Fig. 2.

Pooled estimate prevalence of nineteen menopausal symptoms among middle-aged women

Pooled prevalence, subgroup analysis, and risk factors for somatic symptoms

In somatic domain, hot flashes were one of the most common menopausal symptoms with a pooled prevalence of 52.65% (95% CI 50.24–55.06, I2 = 99.51%, Supplementary Fig. 1). Different continents showed varying prevalence, and Africa had the highest prevalence (64.43%, 95% CI 56.78–71.73) while Oceania had the lowest prevalence (39.92%, 95% CI 30.56–49.66, p < 0.01, Table 1). Among countries containing at least three relevant studies, Egypt had the highest (72.56%, 95% CI 58.15–84.91) and Finland had the lowest (14.54%, 95% CI 5.82–26.29, p < 0.01, Table 1) hot flashes prevalence among middle-aged women. When taking into account the countries’ economic levels, those with high incomes had a significantly lower prevalence of 49.72% (95% CI 46.19–53.25) when compared to upper-middle (54.72%, 95% CI 50.08–59.31), lower-middle (54.17%, 95% CI 49.57–58.73) and low-income countries (65.93%, 95% CI 59.61–71.98, p < 0.01, Table 1). Furthermore, the hot flashes prevalence was substantially lower before 2011 (48.7%, 95% CI 44.78–52.63) than publications after 2011 (55.48%, 95% CI 52.51–58.43, p < 0.01, Table 1). In terms of diagnostic tool, the 10-item Cervantes Scale (CS-10) [16] produced the highest hot flashes prevalence (69.95%, 95% CI 53.7-83.96) while the Simplified Menopausal Index (SMI) [17] had the lowest prevalence (39.26%, 95% CI 27.45–51.74, Table 1). It should be mentioned that hot flashes in middle-aged women appeared to be universally prevalent in both developing countries (54.02%, 95% CI 50.75–57.27) and developed countries (50.39%, 95% CI 46.91–53.86, p = 0.14, Table 1). In order to find the risk factors of hot flashes, we pooled estimate relevant factors. Stratified by menopausal stage, we found middle-aged women in perimenopausal (56.52%, 95% CI 51.54–61.43) and postmenopausal stage (56.74%, 95% CI 52.8-60.64) with dramatically higher hot flashes prevalence than those in premenopausal stage (31.31%, 95% CI 26.46–36.38, p < 0.01, Table 1). However, minimal differences were observed among age (p = 0.69), physical activity (p = 0.82), body mass index (BMI, p = 0.86), residence (p = 0.39), current employment status (p = 0.65), current drinking habit (p = 0.76), current smoking habit (p = 0.48), marital status (p = 0.14) and education level (p = 0.71). Besides, we also pooled estimate prevalence of other somatic symptoms. The prevalence of sleep problems, heart discomfort, headaches, and joint and muscular discomfort were 51.89% (95% CI 49.55–54.22, I2 = 99.41%, Supplementary Figs. 2), 42.12% (95% CI 38.85–45.42, I2 = 99.46%, Supplementary Figs. 3), 43.91% (95% CI 40.64–47.21, I2 = 99.43%, Supplementary Figs. 4) and 65.43% (95% CI 65.51–68.29, I2 = 99.54%, Supplementary Fig. 5). The subgroup analysis and risk factor analysis for these somatic symptoms were listed in Supplementary Tables 2–5, respectively.

Table 1.

Subgroup analysis and pooled estimates of risk factors for hot flashes prevalence among middle-aged women

| Subgroup | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | < 0.01 | ||||||

| China | 32 | 31,022 | 82,951 | 43.39 | 36.78–50.11 | ||

| Nepal | 7 | 1810 | 4386 | 45.91 | 30.52–61.71 | ||

| Nigeria | 8 | 1790 | 3567 | 57.03 | 45.38–68.3 | ||

| Ecuador | 11 | 3132 | 5067 | 62.8 | 56.68–68.72 | ||

| Spain | 7 | 7214 | 14,049 | 50.45 | 42.07–58.81 | ||

| Iran | 11 | 5484 | 8474 | 68.35 | 54.6-80.64 | ||

| India | 41 | 6897 | 13,448 | 52 | 45.71–58.27 | ||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 149 | 226 | 65.93 | 59.61–71.98 | ||

| Turkey | 11 | 4411 | 6548 | 68.92 | 54.7-81.52 | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 8 | 1887 | 2771 | 66.54 | 57.46–75.05 | ||

| Korea | 9 | 6315 | 13,802 | 54.33 | 41.69–66.7 | ||

| Taiwan | 7 | 11,293 | 23,754 | 37.23 | 21.4-54.59 | ||

| UK | 7 | 8538 | 16,002 | 61.77 | 51.04–71.95 | ||

| France | 2 | 609 | 900 | 64.07 | 38.53–85.95 | ||

| Germany | 3 | 1878 | 2789 | 61.11 | 44.42–76.57 | ||

| Belgium | 1 | 487 | 594 | 81.99 | 78.79–84.98 | ||

| Netherlands | 3 | 2608 | 6014 | 57.3 | 35.52–77.7 | ||

| Switzerland | 2 | 594 | 901 | 61.98 | 34.56–85.8 | ||

| Australia | 14 | 5465 | 16,232 | 40.79 | 30.83–51.13 | ||

| Japan | 9 | 4904 | 9286 | 48.68 | 38.62–58.79 | ||

| Oman | 1 | 202 | 472 | 42.8 | 38.36–47.29 | ||

| Multi | 5 | 11,183 | 21,197 | 53.25 | 41.54–64.78 | ||

| Macau | 1 | 251 | 442 | 56.79 | 52.14–61.38 | ||

| Peru | 2 | 865 | 1002 | 92.19 | 71.02–100 | ||

| Pakistan | 8 | 3420 | 6267 | 40.23 | 24.15–57.45 | ||

| Malaysia | 7 | 771 | 1504 | 53.26 | 44.24–62.18 | ||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 429 | 1033 | 42.43 | 35.49–49.53 | ||

| Mexico | 4 | 3354 | 9086 | 47.33 | 27.3-67.82 | ||

| Brazil | 5 | 1610 | 2878 | 50.08 | 41.09–59.07 | ||

| USA | 19 | 12,233 | 24,827 | 51.5 | 46.37–56.62 | ||

| Lebanon | 2 | 522 | 898 | 55.49 | 41.15–69.38 | ||

| Singapore | 2 | 192 | 1151 | 16.67 | 14.57–18.89 | ||

| Greece | 1 | 704 | 1025 | 68.68 | 65.81–71.49 | ||

| Philippines | 1 | 145 | 195 | 74.36 | 67.98–80.26 | ||

| Indonesia | 4 | 808 | 1622 | 37.23 | 10.68–68.85 | ||

| Thailand | 4 | 668 | 1080 | 59.9 | 53.16–66.46 | ||

| Vietnam | 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.29–100 | ||

| Italy | 2 | 544 | 1329 | 44.27 | 31.62–57.32 | ||

| Sweden | 2 | 3485 | 7017 | 57.14 | 40.74–72.77 | ||

| Poland | 1 | 226 | 349 | 64.76 | 59.66–69.69 | ||

| Iraq | 2 | 612 | 842 | 72.7 | 69.62–75.68 | ||

| Finland | 3 | 467 | 4003 | 14.54 | 5.82–26.29 | ||

| Egypt | 5 | 2507 | 3704 | 72.56 | 58.15–84.91 | ||

| Bangladesh | 4 | 578 | 1375 | 44.39 | 24.47–65.29 | ||

| Qatar | 1 | 431 | 1158 | 37.22 | 34.46–40.03 | ||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 129 | 390 | 33.08 | 28.49–37.83 | ||

| Norway | 1 | 8333 | 12,985 | 64.17 | 63.35-65 | ||

| Cambodia | 1 | 118 | 177 | 66.67 | 59.53–73.44 | ||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1030 | 3616 | 28.48 | 27.02–29.97 | ||

| South Africa | 1 | 46 | 63 | 73.02 | 61.3-83.34 | ||

| Israel | 1 | 208 | 612 | 33.99 | 30.28–37.79 | ||

| Libya | 1 | 64 | 86 | 74.42 | 64.61–83.14 | ||

| Hong Kong | 3 | 373 | 1433 | 33.79 | 6.18–69.72 | ||

| Morocco | 1 | 182 | 299 | 60.87 | 55.27–66.33 | ||

| Panama | 1 | 93 | 129 | 72.09 | 64.01–79.53 | ||

| Chile | 1 | 120 | 198 | 60.61 | 53.69–67.31 | ||

| Portugal | 1 | 251 | 728 | 34.48 | 31.07–37.97 | ||

| Bolivia | 1 | 58 | 125 | 46.4 | 37.7-55.21 | ||

| Colombia | 2 | 1279 | 1954 | 80.37 | 42.14–99.8 | ||

| Paraguay | 1 | 117 | 216 | 54.17 | 47.48–60.78 | ||

| Jordan | 2 | 93 | 280 | 27.73 | 0-88.34 | ||

| Continent | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Asia | 183 | 84,073 | 186,451 | 50.99 | 47.67–54.3 | ||

| Africa | 17 | 4738 | 7945 | 64.43 | 56.78–71.73 | ||

| South America | 24 | 10,555 | 17,519 | 63.34 | 56.24–70.16 | ||

| Europe | 38 | 39,790 | 77,277 | 53.67 | 47.61–59.67 | ||

| Oceania | 15 | 6495 | 19,848 | 39.92 | 30.56–49.66 | ||

| North America | 24 | 15,680 | 34,042 | 51.62 | 46.2-57.03 | ||

| Multi | 2 | 3957 | 6526 | 59.94 | 31.08–85.46 | ||

| Income level | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Upper-Middle-Income | 87 | 49,648 | 117,005 | 54.72 | 50.08–59.31 | ||

| Lower-Middle-Income | 97 | 24,848 | 45,670 | 54.17 | 49.57–58.73 | ||

| High-Income | 117 | 87,269 | 180,628 | 49.72 | 46.19–53.25 | ||

| Low-Income | 1 | 149 | 226 | 65.93 | 59.61–71.98 | ||

| Development status | 0.14 | ||||||

| Developing | 189 | 84,578 | 183,516 | 54.02 | 50.75–57.27 | ||

| Developed | 112 | 75,983 | 157,007 | 50.39 | 46.91–53.86 | ||

| Publication date | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Before 2011 | 127 | 51,295 | 118,568 | 48.7 | 44.78–52.63 | ||

| After 2011 | 176 | 113,993 | 231,040 | 55.48 | 52.51–58.43 | ||

| Study size | 0.01 | ||||||

| < 1000 | 223 | 42,756 | 79,780 | 54.45 | 51.58–57.31 | ||

| > 1000 | 80 | 122,532 | 269,828 | 47.74 | 43.49–52.01 | ||

| Study quality | 0.28 | ||||||

| < 8 | 42 | 29,871 | 75,903 | 53.21 | 50.6-55.82 | ||

| ≥ 8 | 261 | 135,417 | 273,705 | 49.44 | 43.19–55.71 | ||

| Diagnostic tool | < 0.01 | ||||||

| KMI [18] | 25 | 30,173 | 75,754 | 42.43 | 36.31–48.67 | ||

| MRS [19] | 82 | 35,063 | 62,420 | 58.52 | 54.85–62.15 | ||

| Others | 73 | 40,151 | 78,506 | 54.77 | 49.38–60.1 | ||

| Face-to-face interview | 62 | 33,366 | 78,534 | 45.85 | 39.84–51.91 | ||

| The Greene Climacteric Scale | 17 | 6618 | 14,279 | 47.63 | 36.15–59.23 | ||

| The Keio questionnaire [20] | 3 | 2331 | 3420 | 61.78 | 39.22–81.95 | ||

| SMI | 2 | 920 | 2338 | 39.26 | 27.45–51.74 | ||

| MENQOL [21] | 28 | 8782 | 20,224 | 54.4 | 47.14–61.58 | ||

| Hot Flush Rating Scale [22] | 7 | 6238 | 11,569 | 56.1 | 47.11–64.89 | ||

| CS-10 | 2 | 1427 | 2190 | 69.95 | 53.7-83.96 | ||

| WHAS [23] | 2 | 219 | 374 | 61.17 | 31.27–87.09 | ||

| Risk factors | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |

| Menopausal stage | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Premenopause | 68 | 12,966 | 50,939 | 31.31 | 26.46–36.38 | ||

| Perimenopause | 75 | 18,525 | 37,720 | 56.52 | 51.54–61.43 | ||

| Postmenopause | 115 | 47,621 | 89,453 | 56.74 | 52.8-60.64 | ||

| Age | 0.69 | ||||||

| < 50 | 13 | 4561 | 14,554 | 49.61 | 34.17–65.09 | ||

| ≥ 50 | 28 | 11,331 | 20,805 | 53.22 | 44.84–61.51 | ||

| Physical activity | 0.82 | ||||||

| Regular | 6 | 1097 | 2138 | 48.95 | 39.28–58.65 | ||

| Irregular | 5 | 950 | 1914 | 51.44 | 32.29–70.37 | ||

| Body mass index | 0.86 | ||||||

| Underweight | 3 | 186 | 314 | 48.45 | 23.82–73.43 | ||

| Normal weight | 3 | 1270 | 2013 | 53.8 | 32.73–74.18 | ||

| Overweight | 5 | 677 | 1249 | 57.58 | 46.74–68.08 | ||

| Obesity | 7 | 1043 | 1853 | 58.81 | 50.38–66.98 | ||

| Urban or rural | 0.39 | ||||||

| Rural | 23 | 9275 | 17,423 | 51.98 | 45.6-58.33 | ||

| Urban | 17 | 10,383 | 22,115 | 57.59 | 46.34–68.47 | ||

| Work | 0.65 | ||||||

| Working | 7 | 1286 | 3124 | 55.55 | 39.86–70.71 | ||

| Non-working | 6 | 806 | 1544 | 61.41 | 41.17–79.8 | ||

| Current drinking habit | 0.76 | ||||||

| Yes | 5 | 914 | 1850 | 48.68 | 39.33–58.08 | ||

| No | 4 | 1274 | 2510 | 51.12 | 38.86–63.3 | ||

| Current smoking | 0.48 | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | 343 | 630 | 53.42 | 42.76–63.95 | ||

| No | 8 | 2983 | 5953 | 49.07 | 43.46–54.7 | ||

| Marital status | 0.14 | ||||||

| Single | 3 | 115 | 241 | 47.97 | 39.25–56.76 | ||

| Married | 3 | 769 | 1353 | 57.03 | 50.99–62.98 | ||

| Divorced or Widowed | 3 | 247 | 399 | 63.67 | 47.24–78.63 | ||

| Education level | 0.71 | ||||||

| < 12 years | 8 | 2177 | 3962 | 52.77 | 42.07–63.34 | ||

| > 12 years | 9 | 1449 | 3105 | 49.88 | 39.11–60.64 | ||

*KMI: The modified Kupperman Menopausal Index; MRS: The Menopause Rating Scale; SMI: Simplified; Menopausal Index; MENQOL: The Menopause-Specific Quality of Life; CS-10:10-item Cervantes Scale; WHAS: the Women’s Health Assessment Scale

Pooled prevalence, subgroup analysis, and risk factors for psychological symptoms

Depression was the psychological symptoms that had the greatest number of included publications. The pooled depression prevalence in middle-aged women was 43.34% (95% CI 40.29–46.42, I2 = 99.65%, Supplementary Fig. 6). The prevalence varied by countries, with Cambodia having the highest prevalence (81.36%, 95% CI 75.26–86.78) and Bolivia having the lowest one (10.4%, 95% CI 5.58–16.43, Table 2). When depression was measured by continents, the greatest estimate was found in South America (54.38%, 95% CI 42.23–66.27), whereas lowest estimate in Europe (33.88%, 95% CI 30.08–37.79, p < 0.01, Table 2). The lowest prevalence was seen in studies conducted in high-income countries (37.64%, 95% CI 33.78–41.58), compared with those in upper-middle (42.78%, 95% CI 37.38–48.26), lower-middle (49.99%, 95% CI 43.74–56.24) and low-income countries (46.02%, 95% CI 39.55–52.55, p < 0.01, Table 2). When studies were categorized by diagnostic tools, we found that studies using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) [24] (58.91%, 95% CI 50.28–67.28) had a significantly higher prevalence of depression than those using the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire [25] (7.21%, 95% CI 1.85–15.32, p < 0.01, Table 2). Besides, results indicated that a significant difference in depression prevalence was found in the pooled estimate among development status (developing/developed, 45.57% vs. 39.08%, p = 0.03, Table 2), publication date (before 2011 or after 2011, 37.48% vs. 47.35%, p < 0.01, Table 2), and study size (more than 1000 participants or less than 1000 participants, 36.09% vs. 45.69%, p < 0.01, Table 2). Similar to most menopausal symptoms, women in premenopausal stage (36.27%, 95% CI 30.14–42.63) shared a significantly lower depression prevalence than those in perimenopausal (47.3%, 95% CI 40.89–53.76) and postmenopausal stage (47.62%, 95% CI 42.48–52.78, p = 0.01, Table 2). It is interesting to note that women with normal weight had lowest prevalence of depression (p < 0.01, Table 2). Moreover, we pooled prevalence of other four psychological symptoms. Physical and mental exhaustion had the highest prevalence (64.13%, 95% CI 60.93–67.27, I2 = 99.54%, Supplementary Fig. 7), followed by irritability (54.37%, 95% CI 50.80–57.92, I2 = 99.35%, Supplementary Fig. 8), anxiety (50.53%, 95% CI 46.65–54.40, I2 = 99.50%, Supplementary Fig. 9), and mood swings (49.03%, 95% CI 43.65–54.43, I2 = 99.55%, Supplementary Fig. 10). The subgroup analysis and risk factor analysis for these psychological symptoms were listed in Supplementary Tables 6–9, respectively.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis and pooled estimates of risk factors for depression prevalence among middle-aged women

| Subgroup | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| China | 24 | 14,860 | 67,753 | 27.51 | 21.97–33.41 | |||||||

| Nepal | 7 | 1463 | 4386 | 42.52 | 19.95–66.86 | |||||||

| Nigeria | 9 | 1187 | 3947 | 30.91 | 16.06–48.11 | |||||||

| Iran | 9 | 3701 | 5580 | 69.31 | 51.43–84.62 | |||||||

| India | 32 | 3585 | 7415 | 49.03 | 39.91–58.17 | |||||||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 104 | 226 | 46.02 | 39.55–52.55 | |||||||

| Turkey | 10 | 2305 | 4587 | 53.37 | 41.41–65.15 | |||||||

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 1699 | 2361 | 64.22 | 46.82–79.89 | |||||||

| UK | 6 | 2122 | 6646 | 35.58 | 29.35–42.07 | |||||||

| France | 2 | 225 | 900 | 24.99 | 22.21–27.88 | |||||||

| Germany | 2 | 269 | 896 | 28.61 | 20.21–37.82 | |||||||

| Belgium | 2 | 228 | 673 | 35.02 | 28.5-41.83 | |||||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 243 | 901 | 25.51 | 17.2-34.83 | |||||||

| Switzerland | 2 | 225 | 901 | 23.49 | 15.25–32.87 | |||||||

| Spain | 5 | 5118 | 13,600 | 34.34 | 28.95–39.93 | |||||||

| Australia | 9 | 2108 | 4563 | 43.64 | 31.75–55.91 | |||||||

| Japan | 5 | 2706 | 5662 | 47.27 | 28.41–66.53 | |||||||

| Oman | 1 | 182 | 472 | 38.56 | 34.21-43 | |||||||

| Multi | 4 | 7238 | 14,740 | 47.24 | 39.18–55.38 | |||||||

| Macau | 1 | 317 | 442 | 71.72 | 67.42–75.83 | |||||||

| Ecuador | 5 | 1188 | 1618 | 72.85 | 66.62–78.66 | |||||||

| Peru | 1 | 578 | 771 | 74.97 | 71.85–77.96 | |||||||

| Malaysia | 5 | 634 | 1316 | 50.74 | 35.29–66.12 | |||||||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 327 | 1033 | 34.95 | 14.07–59.44 | |||||||

| Mexico | 3 | 4345 | 12,938 | 41.23 | 19.75–64.64 | |||||||

| Brazil | 4 | 1219 | 2745 | 43.84 | 34.89-53 | |||||||

| Korea | 5 | 7765 | 50,745 | 40.85 | 22.56–60.56 | |||||||

| Pakistan | 4 | 2788 | 4176 | 46.69 | 25.53–68.49 | |||||||

| Greece | 2 | 515 | 1125 | 45.76 | 42.85–48.69 | |||||||

| Italy | 2 | 132 | 635 | 20.8 | 12.11–31.09 | |||||||

| Iraq | 2 | 306 | 842 | 39.88 | 0-97.57 | |||||||

| USA | 13 | 5403 | 20,366 | 36.21 | 29.13–43.61 | |||||||

| Egypt | 5 | 2192 | 3704 | 62.03 | 45.14–77.54 | |||||||

| Bangladesh | 4 | 879 | 1375 | 71.55 | 46.25–91.18 | |||||||

| Qatar | 2 | 645 | 2259 | 28.57 | 23.74–33.67 | |||||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 101 | 390 | 25.9 | 21.66–30.37 | |||||||

| Cambodia | 1 | 144 | 177 | 81.36 | 75.26–86.78 | |||||||

| Taiwan | 7 | 12,866 | 26,137 | 23.71 | 11.51–38.63 | |||||||

| Sweden | 1 | 72 | 108 | 66.67 | 57.46–75.28 | |||||||

| Indonesia | 2 | 638 | 1318 | 58.23 | 23.07–89.16 | |||||||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1045 | 3616 | 28.9 | 27.43–30.39 | |||||||

| South Africa | 1 | 17 | 63 | 26.98 | 16.66–38.7 | |||||||

| Libya | 1 | 56 | 86 | 65.12 | 54.69–74.88 | |||||||

| Morocco | 1 | 84 | 299 | 28.09 | 23.13–33.33 | |||||||

| Singapore | 1 | 132 | 656 | 20.12 | 17.14–23.28 | |||||||

| Thailand | 2 | 163 | 298 | 54.86 | 35.07–73.89 | |||||||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 89 | 150 | 59.33 | 51.35–67.08 | |||||||

| Portugal | 1 | 266 | 579 | 45.94 | 41.89–50.01 | |||||||

| Poland | 1 | 92 | 241 | 38.17 | 32.13–44.41 | |||||||

| Belarus | 1 | 57 | 119 | 47.9 | 38.95–56.92 | |||||||

| Bolivia | 1 | 13 | 125 | 10.4 | 5.58–16.43 | |||||||

| Canada | 1 | 2436 | 13,216 | 18.43 | 17.78–19.1 | |||||||

| Jordan | 1 | 57 | 143 | 39.86 | 31.96–48.03 | |||||||

| Lebanon | 1 | 111 | 271 | 40.96 | 35.17–46.88 | |||||||

| Finland | 1 | 32 | 158 | 20.25 | 14.32–26.9 | |||||||

| Continent | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Asia | 137 | 58,463 | 189,944 | 45.61 | 41.28–49.98 | |||||||

| Africa | 18 | 3640 | 8325 | 41.71 | 30.11–53.8 | |||||||

| Europe | 31 | 12,025 | 32,273 | 33.88 | 30.08–37.79 | |||||||

| Oceania | 10 | 3153 | 8179 | 42.08 | 31.13–53.44 | |||||||

| South America | 13 | 6136 | 12,202 | 54.38 | 42.23–66.27 | |||||||

| North America | 17 | 12,184 | 46,520 | 35.96 | 29.17–43.04 | |||||||

| Multi | 1 | 1671 | 3006 | 55.59 | 53.81–57.36 | |||||||

| Income level | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Upper-Middle-Income | 63 | 28,084 | 97,591 | 42.78 | 37.38–48.26 | |||||||

| Lower-Middle-Income | 78 | 17,112 | 33,806 | 49.99 | 43.74–56.24 | |||||||

| Low-Income | 1 | 104 | 226 | 46.02 | 39.55–52.55 | |||||||

| High-Income | 84 | 49,145 | 162,747 | 37.64 | 33.78–41.58 | |||||||

| Development status | 0.03 | |||||||||||

| Developing | 146 | 56,394 | 154,561 | 45.57 | 41.33–49.83 | |||||||

| Developed | 79 | 36,380 | 136,803 | 39.08 | 35.26–42.96 | |||||||

| Publication date | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Before 2011 | 91 | 27,348 | 77,182 | 37.48 | 33.77–41.26 | |||||||

| After 2011 | 136 | 69,924 | 223,267 | 47.35 | 43.02–51.7 | |||||||

| Study size | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| < 1000 | 173 | 27,620 | 61,286 | 45.69 | 42.09–49.31 | |||||||

| > 1000 | 54 | 69,652 | 239,163 | 36.09 | 30.93–41.42 | |||||||

| Study quality | 0.76 | |||||||||||

| < 8 | 35 | 15,311 | 52,827 | 44.41 | 37.07–51.87 | |||||||

| ≥ 8 | 192 | 81,961 | 247,622 | 43.14 | 39.79–46.53 | |||||||

| Diagnostic tool | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| KMI | 13 | 12,177 | 47,121 | 29.78 | 22.36–37.76 | |||||||

| MRS | 66 | 28,908 | 51,731 | 58.64 | 53.92–63.29 | |||||||

| Face-to-face interview | 44 | 11,745 | 47,432 | 29.38 | 24.76–34.21 | |||||||

| Others | 33 | 18,916 | 41,213 | 34.87 | 28.16–41.9 | |||||||

| The Greene Climacteric Scale | 13 | 4736 | 10,813 | 47.36 | 39.31–55.48 | |||||||

| SMI | 2 | 695 | 2338 | 28.46 | 4.94–61.45 | |||||||

| MENQOL | 22 | 4569 | 8439 | 58.91 | 50.28–67.28 | |||||||

| SDS [26] | 4 | 778 | 4254 | 31.56 | 3.91–70.18 | |||||||

| PHQ-9 [27] | 6 | 3320 | 15,512 | 44.32 | 19.73–70.5 | |||||||

| BDI [28] | 10 | 1057 | 2670 | 40.09 | 26.77–54.18 | |||||||

| CES-D [29] | 9 | 8370 | 61,762 | 31.29 | 22.71–40.57 | |||||||

| HAM-D [30] | 3 | 1834 | 3608 | 49.65 | 39.12–60.19 | |||||||

| Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire | 2 | 167 | 3556 | 7.12 | 1.85–15.32 | |||||||

| Risk factors | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | ||||||

| Menopausal stage | 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Premenopause | 58 | 13,274 | 67,522 | 36.27 | 30.14–42.63 | |||||||

| Perimenopause | 57 | 12,111 | 38,119 | 47.3 | 40.89–53.76 | |||||||

| Postmenopause | 97 | 31,129 | 91,152 | 47.62 | 42.48–52.78 | |||||||

| Age | 0.97 | |||||||||||

| < 50 | 14 | 1604 | 6203 | 36.77 | 24.91–49.5 | |||||||

| ≥ 50 | 23 | 3302 | 10,049 | 37.08 | 28.2-46.42 | |||||||

| Physical activity | 0.85 | |||||||||||

| Regular | 7 | 1053 | 5260 | 38.11 | 15.37–64.02 | |||||||

| Irregular | 7 | 2119 | 10,091 | 41.05 | 23.69–59.62 | |||||||

| Body mass index | < 0.01 | |||||||||||

| Underweight | 3 | 227 | 929 | 24.35 | 21.62–27.18 | |||||||

| Normal weight | 3 | 1965 | 11,380 | 17.56 | 15.62–19.58 | |||||||

| Overweight | 7 | 1611 | 7935 | 27.09 | 16.99–38.54 | |||||||

| Obesity | 9 | 1479 | 5285 | 43.1 | 25.46–61.67 | |||||||

| Urban or rural | 0.81 | |||||||||||

| Rural | 20 | 7027 | 17,856 | 43.73 | 32.44–55.35 | |||||||

| Urban | 10 | 5862 | 19,046 | 46.95 | 24.5-70.07 | |||||||

| Work | 0.92 | |||||||||||

| Working | 11 | 2691 | 10,574 | 39.36 | 26.42–53.06 | |||||||

| Non-working | 10 | 1532 | 5031 | 40.61 | 24.17–58.2 | |||||||

| Current drinking habit | 0.24 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 5 | 985 | 6496 | 16.15 | 9.56–24.02 | |||||||

| No | 5 | 4940 | 46,123 | 27.99 | 11.14–48.88 | |||||||

| Current smoking | 0.31 | |||||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 787 | 3002 | 25.61 | 17.38–34.74 | |||||||

| No | 10 | 10,035 | 77,160 | 20.26 | 13.18–28.41 | |||||||

| Marital status | 0.69 | |||||||||||

| Single, Divorced or Widowed | 12 | 1984 | 8689 | 40.65 | 22.69–59.97 | |||||||

| Married | 12 | 4893 | 27,465 | 35.41 | 18.91–53.92 | |||||||

| Education level | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| < 12 years | 16 | 6187 | 36,671 | 35.98 | 22.08–51.2 | |||||||

| > 12 years | 12 | 5468 | 45,214 | 26.03 | 13.99–40.05 | |||||||

*KMI: The modified Kupperman Menopausal Index; MRS: The Menopause Rating Scale; SMI: Simplified Menopausal Index; MENQOL: The Menopause-Specific Quality of Life; SDS: Self-rating Depression Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; BDI: Beck depression inventory; CES-D: the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Pooled prevalence, subgroup analysis, and risk factors for urogenital symptoms

Sexual problems account for the highest prevalence (45.45%, 95% CI 41.89–49.04, I2 = 99.56%, Supplementary Fig. 11) among urogenital symptoms, with vagina dryness (37.34%, 95% CI 34.30-40.44, I2 = 99.40%, Supplementary Fig. 12) and urinary problems (34.49%, 95% CI 31.70-37.34, I2 = 99.42%, Supplementary Fig. 13) following closely behind. Moreover, the results indicated that there was a substantial variation in the prevalence of these three urogenital symptoms among countries (p < 0.01, Table 3). When assessed by continents, South America (60.94%, 95% CI 53.24–68.38, p < 0.01, Table 3) had the highest estimate of sexual problems. Nevertheless, there was no statistical difference was found in vagina dryness (p = 0.45) and urinary symptoms (p = 0.11) by continents (Table 3). Additionally, compared with publications after 2011, the prevalence of sexual problems (40.86% vs. 49.08%, p = 0.02), vagina dryness (33.23% vs. 40.47%, p = 0.02) and urinary problems (29.38% vs. 37.73%, p < 0.01) was consistently lower in publications after 2011 (Table 3). However, there was minimal difference observed among development status of countries in urogenital symptoms (sexual problems, 45.37% vs. 45.94%, p = 0.87; vagina dryness, 38.28% vs. 36.1%, p = 0.47, urinary symptoms, 35.89% vs. 31.58%, p = 0.13, Table 3). Studies with more than 1000 participants reported a lower prevalence of vagina dryness (32.13% vs. 38.77%, p = 0.03) and urinary symptoms (29.52% vs. 35.97%, p = 0.03) than those with less than 1000 participants (Table 3). Prevalence varied significantly by diagnostic tools, with the highest by using the Greene Climacteric Scale [31] (63.44%, 95% CI 52.47–73.75) for sexual problems, CS-10 (51.48%, 95% CI 22.27–80.14) for vagina dryness, and MENQOL (48.13%, 95% CI 40.32–55.99) for urinary problems, shown in Table 3. With regard to menopausal stage, we found that for each of the three urogenital symptoms, women in postmenopausal stage resulted in the highest prevalence (53.97%, 44.81%, and 40.27% for sexual problems, vagina dryness, and urinary problems, respectively), followed by premenopausal stage (35.24%, 21.16%, and 22.21% for sexual problems, vagina dryness, and urinary problems, respectively) and perimenopausal stage (48.82%, 36.07%, and 33.29% for sexual problems, vagina dryness, and urinary problems, respectively, p < 0.01, Table 3). Intriguingly, we found BMI of middle-aged women were linearly correlated with prevalence of urinary problems, those of obesity had a highest prevalence of 31.73% (95% CI 19.13–45.86), followed by overweight (20.41%, 95% CI 10.24–32.94), normal weight (13.03%, 95% CI 10.72–15.54), and underweight (10.61%, 95% CI 3.09–21.71, p = 0.01, Table 3). The subgroup analysis and risk factor analysis for these urogenital symptoms were listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis and pooled estimates of risk factors for prevalence of urogenital symptoms among middle-aged women

| 1. Sexual Problems | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Country | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| China | 21 | 22,284 | 64,498 | 40.76 | 30.12–51.86 | ||||

| Nepal | 7 | 1655 | 4386 | 46.3 | 23.24–70.23 | ||||

| Nigeria | 7 | 1299 | 3020 | 46.78 | 20.42–74.15 | ||||

| Iran | 8 | 3265 | 6517 | 53.06 | 30.04–75.42 | ||||

| India | 26 | 2924 | 6522 | 45.5 | 32.58–58.72 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 61 | 226 | 26.99 | 21.39–32.98 | ||||

| Turkey | 7 | 1018 | 2529 | 48.47 | 30.78–66.36 | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 1240 | 2238 | 47.27 | 33.43–61.33 | ||||

| UK | 4 | 2368 | 5282 | 45.66 | 42.33–49.02 | ||||

| France | 2 | 351 | 900 | 38.31 | 32.57–44.22 | ||||

| Germany | 2 | 337 | 896 | 36.71 | 30.1-43.59 | ||||

| Belgium | 2 | 318 | 673 | 50.19 | 39.75–60.61 | ||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 417 | 901 | 45.83 | 40.88–50.81 | ||||

| Switzerland | 2 | 315 | 901 | 31.06 | 12.81–53.06 | ||||

| Spain | 5 | 1659 | 3346 | 50.23 | 45.51–54.94 | ||||

| Australia | 8 | 2600 | 4347 | 60.52 | 51.14–69.53 | ||||

| Japan | 2 | 1639 | 2249 | 73.29 | 69.44–76.98 | ||||

| Oman | 1 | 121 | 472 | 25.64 | 21.79–29.68 | ||||

| Macau | 1 | 311 | 442 | 70.36 | 66.01–74.53 | ||||

| Ecuador | 5 | 975 | 1502 | 64.88 | 52.49–76.35 | ||||

| Peru | 1 | 453 | 771 | 58.75 | 55.26–62.21 | ||||

| Malaysia | 6 | 576 | 1335 | 47.35 | 31.92–63.03 | ||||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 123 | 1033 | 13.49 | 0.89–37.06 | ||||

| Brazil | 2 | 934 | 1775 | 56.59 | 42.97–69.72 | ||||

| Korea | 3 | 2797 | 4352 | 47.41 | 15.5-80.55 | ||||

| Singapore | 2 | 255 | 1151 | 21.43 | 13.53–30.56 | ||||

| Pakistan | 5 | 2139 | 4412 | 28.1 | 13.2-45.96 | ||||

| Greece | 2 | 670 | 1125 | 60.19 | 55.6-64.69 | ||||

| Philippines | 1 | 64 | 195 | 32.82 | 26.39–39.59 | ||||

| Indonesia | 3 | 602 | 1377 | 52.7 | 28.52–76.22 | ||||

| Taiwan | 3 | 10,313 | 21,263 | 37.59 | 19.93–57.12 | ||||

| Thailand | 3 | 190 | 448 | 41.71 | 16.75–69.17 | ||||

| Vietnam | 1 | 69 | 100 | 69 | 59.55–77.73 | ||||

| Italy | 1 | 96 | 301 | 31.89 | 26.74–37.28 | ||||

| Iraq | 1 | 150 | 342 | 43.86 | 38.63–49.15 | ||||

| USA | 8 | 3207 | 12,185 | 34.98 | 26.71–43.72 | ||||

| Egypt | 5 | 1573 | 3704 | 39.5 | 10.13–73.92 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 2 | 409 | 899 | 47.51 | 17.51–78.54 | ||||

| Mexico | 1 | 228 | 290 | 78.62 | 73.7-83.16 | ||||

| Qatar | 1 | 280 | 1158 | 24.18 | 21.76–26.69 | ||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 93 | 390 | 23.85 | 19.74–28.21 | ||||

| Cambodia | 1 | 54 | 177 | 30.51 | 23.93–37.51 | ||||

| Sweden | 1 | 67 | 109 | 61.47 | 52.12–70.42 | ||||

| Multi | 2 | 2959 | 7797 | 35.41 | 17.77–55.39 | ||||

| South Africa | 1 | 38 | 63 | 60.32 | 47.9-72.11 | ||||

| Libya | 1 | 42 | 86 | 48.84 | 38.29–59.44 | ||||

| Morocco | 1 | 60 | 299 | 20.07 | 15.71–24.81 | ||||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 96 | 150 | 64 | 56.13–71.51 | ||||

| Portugal | 1 | 223 | 728 | 30.63 | 27.33–34.03 | ||||

| Poland | 1 | 149 | 241 | 61.83 | 55.59–67.87 | ||||

| Belarus | 1 | 83 | 119 | 69.75 | 61.16–77.7 | ||||

| Bolivia | 1 | 64 | 125 | 51.2 | 42.41–59.95 | ||||

| Lebanon | 1 | 141 | 271 | 52.03 | 46.06–57.97 | ||||

| Continent | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Asia | 117 | 52,808 | 128,906 | 44 | 39.15–48.91 | ||||

| Africa | 16 | 3073 | 7398 | 42.33 | 26.76–58.72 | ||||

| Europe | 27 | 9233 | 20,313 | 46.34 | 42.06–50.66 | ||||

| Oceania | 8 | 2600 | 4347 | 60.52 | 51.14–69.53 | ||||

| South America | 9 | 2426 | 4173 | 60.94 | 53.24–68.38 | ||||

| North America | 9 | 3435 | 12,475 | 40 | 27.99–52.65 | ||||

| Multi | 1 | 779 | 3006 | 25.91 | 24.36–27.5 | ||||

| Income level | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Upper-Middle-Income | 52 | 28,061 | 77,206 | 48.04 | 41.79–54.32 | ||||

| Lower-Middle-Income | 71 | 14,441 | 33,037 | 43.89 | 36.66–51.26 | ||||

| Low-Income | 1 | 61 | 226 | 26.99 | 21.39–32.98 | ||||

| High-Income | 63 | 31,791 | 70,149 | 45.38 | 41.2–49.6 | ||||

| Development status | 0.87 | ||||||||

| Developing | 122 | 51,788 | 127,944 | 45.37 | 40.4-50.38 | ||||

| Developed | 64 | 21,787 | 49,668 | 45.94 | 41.68–50.22 | ||||

| Publication date | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Before 2011 | 82 | 20,899 | 53,390 | 40.86 | 36.38–45.41 | ||||

| After 2011 | 105 | 53,455 | 127,228 | 49.08 | 43.9-54.27 | ||||

| Study size | 0.27 | ||||||||

| < 1000 | 151 | 23,542 | 50,476 | 46.29 | 42.13–50.47 | ||||

| > 1000 | 36 | 50,812 | 130,142 | 42.04 | 35.89–48.32 | ||||

| Study quality | 0.99 | ||||||||

| < 8 | 26 | 16,966 | 48,856 | 45.52 | 37.39–53.76 | ||||

| ≥ 8 | 161 | 57,388 | 131,762 | 45.44 | 41.52–49.39 | ||||

| Diagnostic tool | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| KMI | 13 | 17,151 | 48,291 | 40.62 | 29.52–52.22 | ||||

| MRS | 64 | 19,335 | 41,588 | 46.42 | 39.9–53 | ||||

| Face-to-face interview | 39 | 10,180 | 34,326 | 37.1 | 30.12–44.36 | ||||

| Others | 37 | 17,387 | 39,061 | 41.94 | 35.32–48.69 | ||||

| The Greene Climacteric Scale | 11 | 4607 | 6803 | 63.44 | 52.47–73.75 | ||||

| MENQOL | 21 | 4252 | 8039 | 57.48 | 46.09–68.48 | ||||

| FSFI [32] | 2 | 1442 | 2510 | 53.13 | 41.9-64.21 | ||||

| Risk factors | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Menopausal stage | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Premenopause | 43 | 9217 | 34,406 | 35.24 | 28.76-42 | ||||

| Perimenopause | 47 | 9674 | 22,999 | 48.82 | 41.59–56.08 | ||||

| Postmenopause | 73 | 24,494 | 49,059 | 53.97 | 47.39–60.48 | ||||

| Age | 0.69 | ||||||||

| < 50 | 5 | 494 | 1210 | 39.62 | 31.42–48.12 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 11 | 2400 | 4795 | 44.28 | 24.43–65.13 | ||||

| Urban or rural | 0.17 | ||||||||

| Rural | 15 | 4677 | 9669 | 49.18 | 32.86–65.59 | ||||

| Urban | 6 | 3316 | 6123 | 69.83 | 45.49–89.38 | ||||

| Work | 0.22 | ||||||||

| Working | 3 | 882 | 1877 | 59.1 | 38.64–78.06 | ||||

| Non-working | 2 | 161 | 185 | 85.14 | 46.35–100 | ||||

| 2. Vagina dryness | |||||||||

| Subgroup | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Country | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Nepal | 7 | 1564 | 4386 | 47.05 | 25.15–69.56 | ||||

| Nigeria | 5 | 565 | 2138 | 34.82 | 19.22–52.28 | ||||

| Iran | 9 | 2100 | 4703 | 42.87 | 22.79–64.25 | ||||

| India | 22 | 2035 | 6862 | 31.6 | 21.07–43.17 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 69 | 226 | 30.53 | 24.68–36.71 | ||||

| Turkey | 7 | 1149 | 3215 | 41.73 | 26.27–58.07 | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 1316 | 2361 | 50.68 | 37.35–63.96 | ||||

| UK | 5 | 1543 | 5531 | 27.08 | 22.09–32.38 | ||||

| France | 2 | 252 | 900 | 25.24 | 12.17–41.12 | ||||

| Germany | 2 | 176 | 896 | 19.63 | 17.08–22.3 | ||||

| Belgium | 2 | 250 | 673 | 50.24 | 17.63–82.73 | ||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 276 | 901 | 30.63 | 27.65–33.68 | ||||

| Switzerland | 2 | 218 | 901 | 21.23 | 8.37–37.96 | ||||

| Spain | 4 | 1350 | 2447 | 56.95 | 26.32–84.89 | ||||

| Oman | 1 | 70 | 472 | 14.83 | 11.76–18.19 | ||||

| Macau | 1 | 213 | 442 | 48.19 | 43.54–52.86 | ||||

| Taiwan | 4 | 10,545 | 22,623 | 30.97 | 17.38–46.46 | ||||

| Ecuador | 5 | 808 | 1565 | 51.56 | 31.7-71.16 | ||||

| Peru | 1 | 265 | 771 | 34.37 | 31.06–37.76 | ||||

| Malaysia | 7 | 700 | 1504 | 49.45 | 41.46–57.45 | ||||

| China | 12 | 5626 | 22,135 | 34.44 | 23.16–46.67 | ||||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 160 | 1033 | 17.38 | 3.91–37.6 | ||||

| Australia | 6 | 674 | 2314 | 26.95 | 10.81–47.08 | ||||

| Mexico | 2 | 1829 | 7925 | 38.93 | 8.78–74.92 | ||||

| Brazil | 3 | 813 | 2375 | 30.21 | 20.72–40.63 | ||||

| Korea | 5 | 3165 | 5665 | 52.15 | 45.74–58.52 | ||||

| Japan | 2 | 948 | 3030 | 31.95 | 26.89–37.23 | ||||

| Singapore | 2 | 267 | 1151 | 22.94 | 18.65–27.53 | ||||

| USA | 11 | 4555 | 17,589 | 30.51 | 24.39–37.01 | ||||

| Pakistan | 4 | 1139 | 3549 | 33.11 | 21.6-45.74 | ||||

| Greece | 2 | 433 | 1125 | 45.7 | 27.51–64.49 | ||||

| Philippines | 1 | 115 | 195 | 58.97 | 51.98–65.8 | ||||

| Indonesia | 3 | 431 | 1377 | 46.27 | 16.51–77.57 | ||||

| Thailand | 3 | 228 | 448 | 50.97 | 39.86–62.03 | ||||

| Vietnam | 1 | 90 | 100 | 90 | 83.25–95.22 | ||||

| Italy | 1 | 48 | 301 | 15.95 | 12.01–20.31 | ||||

| Sweden | 2 | 2061 | 7016 | 37.32 | 20.69–55.65 | ||||

| Poland | 2 | 254 | 590 | 44.24 | 30.04–58.94 | ||||

| Iraq | 2 | 368 | 842 | 41.73 | 23.23–61.52 | ||||

| Egypt | 5 | 1459 | 3704 | 43.08 | 20.53–67.27 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 2 | 427 | 899 | 49.2 | 24.12–74.5 | ||||

| Qatar | 1 | 296 | 1158 | 25.56 | 23.09–28.12 | ||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 107 | 390 | 27.44 | 23.11–31.98 | ||||

| Cambodia | 1 | 66 | 177 | 37.29 | 30.29–44.56 | ||||

| Multi | 3 | 3807 | 11,317 | 32.72 | 20-46.89 | ||||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1263 | 3616 | 34.93 | 33.38–36.49 | ||||

| Libya | 1 | 21 | 86 | 24.42 | 15.86–34.11 | ||||

| Morocco | 1 | 45 | 299 | 15.05 | 11.21–19.34 | ||||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 67 | 150 | 44.67 | 36.77–52.7 | ||||

| Portugal | 1 | 229 | 728 | 31.46 | 28.13–34.88 | ||||

| Belarus | 1 | 26 | 119 | 21.85 | 14.84–29.76 | ||||

| Bolivia | 1 | 51 | 125 | 40.8 | 32.32–49.57 | ||||

| Colombia | 1 | 626 | 1739 | 36 | 33.76–38.27 | ||||

| Lebanon | 1 | 35 | 271 | 12.92 | 9.17–17.19 | ||||

| Continent | 0.45 | ||||||||

| Asia | 109 | 33,227 | 89,138 | 39.35 | 35.03–43.75 | ||||

| Africa | 13 | 2159 | 6453 | 35.13 | 24.18–46.94 | ||||

| Europe | 29 | 8702 | 26,919 | 34.54 | 28.14–41.23 | ||||

| South America | 11 | 2563 | 6575 | 41.51 | 31.16–52.26 | ||||

| Oceania | 7 | 1937 | 5930 | 28.07 | 13.72–45.19 | ||||

| North America | 13 | 6384 | 25,514 | 31.77 | 25.12–38.81 | ||||

| Multi | 2 | 2221 | 6526 | 32.52 | 12.09–57.3 | ||||

| Income level | 0.11 | ||||||||

| Lower-Middle-Income | 65 | 10,282 | 29,818 | 37.69 | 31.33–44.27 | ||||

| Low-Income | 1 | 69 | 226 | 30.53 | 24.68–36.71 | ||||

| Upper-Middle-Income | 47 | 13,309 | 46,172 | 40.24 | 35.04–45.56 | ||||

| High-Income | 71 | 33,533 | 90,839 | 35.21 | 31.25–39.28 | ||||

| Development status | 0.47 | ||||||||

| Developing | 112 | 33,419 | 95,452 | 38.28 | 33.99–42.67 | ||||

| Developed | 71 | 23,137 | 68,597 | 36.1 | 32.07–40.22 | ||||

| Publication date | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Before 2011 | 79 | 18,895 | 69,009 | 33.23 | 29.2-37.38 | ||||

| After 2011 | 105 | 38,298 | 98,046 | 40.47 | 36.18–44.84 | ||||

| Study size | 0.03 | ||||||||

| < 1000 | 146 | 18,308 | 47,658 | 38.77 | 35.13–42.48 | ||||

| > 1000 | 38 | 38,885 | 119,397 | 32.13 | 27.61–36.82 | ||||

| Study quality | 0.79 | ||||||||

| < 8 | 22 | 7590 | 24,131 | 36.24 | 27.93–44.99 | ||||

| ≥ 8 | 162 | 49,603 | 142,924 | 37.49 | 34.23–40.82 | ||||

| Diagnostic tool | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| MRS | 66 | 15,944 | 42,577 | 39.92 | 34.81–45.14 | ||||

| Face-to-face interview | 42 | 9291 | 45,059 | 25.4 | 20.94–30.14 | ||||

| KMI | 4 | 1942 | 7182 | 27.7 | 12.01–46.92 | ||||

| MENQOL | 20 | 3598 | 8070 | 43.86 | 32.5-55.56 | ||||

| The Keio questionnaire | 2 | 948 | 3030 | 31.95 | 26.89–37.23 | ||||

| Others | 44 | 21,245 | 51,669 | 43 | 37.18–48.92 | ||||

| The Greene Climacteric Scale | 4 | 3297 | 7278 | 39.67 | 21.68–59.23 | ||||

| CS-10 | 2 | 928 | 2190 | 51.48 | 22.27–80.14 | ||||

| Risk factors | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Menopausal stage | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Premenopause | 40 | 4743 | 21,621 | 21.16 | 16.42–26.3 | ||||

| Perimenopause | 46 | 7186 | 20,967 | 36.07 | 30.54–41.78 | ||||

| Postmenopause | 74 | 22,880 | 54,304 | 44.81 | 39.03–50.67 | ||||

| Age | 0.16 | ||||||||

| < 50 | 5 | 405 | 1078 | 43.39 | 31.34–55.85 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 15 | 5088 | 14,666 | 32.27 | 23.06–42.22 | ||||

| Urban or rural | 0.11 | ||||||||

| Rural | 11 | 2648 | 9005 | 29.49 | 18.91–41.31 | ||||

| Urban | 6 | 2184 | 7143 | 61.64 | 24.5-92.26 | ||||

| 3.Urinary problems | |||||||||

| Subgroup | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Country | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| China | 23 | 13,804 | 64,261 | 24.2 | 18.98–29.84 | ||||

| Nepal | 6 | 1097 | 2386 | 39.38 | 21.98–58.3 | ||||

| Nigeria | 7 | 452 | 3020 | 19.37 | 5.8-38.27 | ||||

| Iran | 9 | 2578 | 6819 | 44.1 | 24.39–64.82 | ||||

| India | 26 | 3066 | 7578 | 40.09 | 31.06–49.46 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 1 | 59 | 226 | 26.11 | 20.57–32.04 | ||||

| Turkey | 9 | 2315 | 4535 | 51.6 | 39.48–63.64 | ||||

| Saudi Arabia | 7 | 1312 | 2361 | 51.37 | 39.34–63.31 | ||||

| UK | 4 | 1895 | 5447 | 31.53 | 24.27–39.28 | ||||

| France | 2 | 210 | 900 | 23.32 | 20.61–26.15 | ||||

| Germany | 3 | 1020 | 2789 | 28 | 13.78–44.94 | ||||

| Belgium | 2 | 198 | 673 | 39.84 | 13.71–69.54 | ||||

| Netherlands | 2 | 324 | 901 | 35.23 | 29.41–41.27 | ||||

| Switzerland | 2 | 171 | 901 | 16.65 | 6.68–29.92 | ||||

| Spain | 4 | 570 | 1676 | 33 | 17.6-50.54 | ||||

| Oman | 1 | 112 | 472 | 23.73 | 19.99–27.68 | ||||

| Macau | 1 | 244 | 442 | 55.2 | 50.54–59.82 | ||||

| Taiwan | 5 | 9654 | 22,784 | 29.96 | 21.2-39.52 | ||||

| Ecuador | 5 | 797 | 1684 | 45.63 | 32.37–59.21 | ||||

| Peru | 1 | 429 | 771 | 55.64 | 52.12–59.14 | ||||

| Malaysia | 7 | 426 | 1504 | 28.99 | 21.69–36.87 | ||||

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 235 | 1033 | 24.01 | 15.21–34.08 | ||||

| Brazil | 3 | 547 | 2375 | 21.02 | 15.39–27.27 | ||||

| China | 1 | 13,804 | 64,261 | 8.69 | 8.14–9.26 | ||||

| Korea | 4 | 2506 | 4922 | 46.77 | 33.17–60.61 | ||||

| Japan | 2 | 1161 | 3030 | 42.07 | 17.07–69.49 | ||||

| Singapore | 2 | 245 | 1151 | 21.2 | 18.39–24.16 | ||||

| Pakistan | 7 | 1803 | 5467 | 34.34 | 23.09–46.55 | ||||

| Philippines | 1 | 129 | 195 | 66.15 | 59.35–72.64 | ||||

| Indonesia | 2 | 255 | 377 | 45.83 | 0.43–97.41 | ||||

| Thailand | 3 | 165 | 448 | 36.01 | 9.4-68.44 | ||||

| Vietnam | 1 | 59 | 100 | 59 | 49.18–68.48 | ||||

| Australia | 7 | 2373 | 10,803 | 35.97 | 21.29–52.12 | ||||

| Italy | 2 | 60 | 635 | 9.34 | 3.84–16.85 | ||||

| Poland | 2 | 198 | 590 | 34.17 | 25.47–43.44 | ||||

| Iraq | 3 | 923 | 1949 | 46.52 | 30.81–62.59 | ||||

| USA | 5 | 1886 | 9877 | 32.52 | 18.43–48.43 | ||||

| Egypt | 5 | 1522 | 3704 | 45.16 | 32.59–58.05 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 3 | 798 | 2489 | 34.73 | 8.6-67.34 | ||||

| Qatar | 1 | 266 | 1158 | 22.97 | 20.59–25.44 | ||||

| United Arab Emirates | 1 | 104 | 390 | 26.67 | 22.39–31.17 | ||||

| Cambodia | 1 | 83 | 177 | 46.89 | 39.57–54.28 | ||||

| Sweden | 1 | 55 | 108 | 50.93 | 41.47–60.35 | ||||

| New Zealand | 1 | 160 | 3616 | 4.42 | 3.78–5.12 | ||||

| Multi | 1 | 145 | 360 | 40.28 | 35.26–45.4 | ||||

| Morocco | 1 | 57 | 299 | 19.06 | 14.8-23.72 | ||||

| Hong Kong | 1 | 59 | 150 | 39.33 | 31.64–47.29 | ||||

| Portugal | 1 | 111 | 728 | 15.25 | 12.72–17.95 | ||||

| Belarus | 1 | 18 | 119 | 15.13 | 9.19–22.18 | ||||

| Greece | 1 | 21 | 100 | 21 | 13.52–29.58 | ||||

| Colombia | 1 | 452 | 1739 | 25.99 | 23.96–28.08 | ||||

| Jordan | 1 | 43 | 143 | 30.07 | 22.81–37.87 | ||||

| Lebanon | 1 | 68 | 271 | 25.09 | 20.1-30.44 | ||||

| Continent | 0.11 | ||||||||

| Asia | 131 | 44,346 | 146,209 | 36.76 | 33.21–40.39 | ||||

| Africa | 14 | 2090 | 7249 | 28.43 | 17.42–40.92 | ||||

| Europe | 28 | 4996 | 15,927 | 27.93 | 23.14–32.98 | ||||

| South America | 10 | 2225 | 6569 | 36.66 | 26.38–47.6 | ||||

| Oceania | 8 | 2533 | 14,419 | 30.83 | 15.96–48.07 | ||||

| North America | 5 | 1886 | 9877 | 32.52 | 18.43–48.43 | ||||

| Income level | < 0.05 | ||||||||

| Upper-Middle-Income | 59 | 20,999 | 89,587 | 32.6 | 28.01–37.35 | ||||

| Lower-Middle-Income | 72 | 12,202 | 33,915 | 37.79 | 32.29–43.46 | ||||

| Low-Income | 1 | 59 | 226 | 26.11 | 20.57–32.04 | ||||

| High-Income | 64 | 24,816 | 76,522 | 32.74 | 28.74–36.87 | ||||

| Development status | 0.13 | ||||||||

| Developing | 133 | 43,025 | 146,131 | 35.89 | 32.27–39.6 | ||||

| Developed | 63 | 15,051 | 54,119 | 31.58 | 27.54–35.75 | ||||

| Publication date | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Before 2011 | 75 | 11,784 | 52,557 | 29.38 | 25.6-33.31 | ||||

| After 2011 | 121 | 46,292 | 147,693 | 37.73 | 33.98–41.56 | ||||

| Study size | 0.03 | ||||||||

| < 1000 | 153 | 18,038 | 49,798 | 35.97 | 32.69–39.32 | ||||

| > 1000 | 43 | 40,038 | 150,452 | 29.52 | 24.71–34.56 | ||||

| Study quality | 0.54 | ||||||||

| < 8 | 27 | 11,101 | 54,188 | 32.06 | 23.88–40.84 | ||||

| ≥ 8 | 169 | 46,975 | 146,062 | 34.89 | 31.94–37.89 | ||||

| Diagnostic tool | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| KMI | 16 | 11,479 | 56,232 | 22.96 | 17.18–29.31 | ||||

| MRS | 63 | 13,085 | 34,214 | 39.62 | 34.24–45.13 | ||||

| Face-to-face interview | 45 | 10,015 | 47,253 | 24.84 | 20.66–29.28 | ||||

| Others | 48 | 17,653 | 49,128 | 35.33 | 30-40.85 | ||||

| MENQOL | 20 | 3955 | 8203 | 48.13 | 40.32–55.99 | ||||

| The Keio questionnaire | 2 | 1161 | 3030 | 42.07 | 17.07–69.49 | ||||

| CS-10 | 2 | 728 | 2190 | 43.08 | 12.38–77.13 | ||||

| Risk factors | Studies | Event | Total | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | P value | |||

| Menopausal stage | < 0.01 | ||||||||

| Premenopause | 43 | 6877 | 34,966 | 22.21 | 17.31–27.53 | ||||

| Perimenopause | 47 | 7419 | 24,305 | 33.29 | 27.49–39.36 | ||||

| Postmenopause | 82 | 108,693 | 148,061 | 40.27 | 34.59–46.09 | ||||

| Age | 0.08 | ||||||||

| < 50 | 8 | 2223 | 10,596 | 24.27 | 15.61–34.12 | ||||

| ≥ 50 | 17 | 2224 | 7402 | 36.32 | 27.04–46.14 | ||||

| Body mass index | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Underweight | 2 | 37 | 392 | 10.61 | 3.09–21.71 | ||||

| Normal weight | 2 | 422 | 3215 | 13.03 | 10.72–15.54 | ||||

| Overweight | 3 | 187 | 1112 | 20.41 | 10.24–32.94 | ||||

| Obesity | 4 | 290 | 856 | 31.73 | 19.13–45.86 | ||||

| Urban or rural | 0.32 | ||||||||

| Rural | 14 | 3685 | 10,852 | 40.59 | 29.99–51.66 | ||||

| Urban | 8 | 3179 | 8001 | 53.96 | 30.4-76.62 | ||||

| Work | 0.36 | ||||||||

| Working | 4 | 547 | 1938 | 34.13 | 4.59–73.27 | ||||

| Non-working | 3 | 217 | 416 | 56.56 | 29.81–81.43 | ||||

| Education level | 0.83 | ||||||||

| < 12 years | 5 | 1130 | 4691 | 30.95 | 21.24–41.58 | ||||

| > 12 years | 4 | 239 | 675 | 32.3 | 20.14–45.73 | ||||

*KMI: The modified Kupperman Menopausal Index; MRS: The Menopause Rating Scale; MENQOL: The Menopause-Specific Quality of Life; CS-10:10-item Cervantes Scale; FSFI: The Female Sexual Function Index

Pooled prevalence, subgroup analysis, and risk factors for other symptoms

The prevalence of poor memory, difficulty concentrating, formication, changing in the appearance, texture, or tone of skin, increased facial hair, and drying skin were 54.44% (95% CI 48.87–59.95, I2 = 99.43%, Supplementary Figs. 14), 44.85% (95% CI 37.71–52.09, I2 = 99.32%, Supplementary Figs. 15), 20.50% (95% CI 13.44–28.60, I2 = 99.75%, Supplementary Figs. 16), 46.48% (95% CI 36.21–56.89, I2 = 98.75%, Supplementary Figs. 17), 27.19% (95% CI 21.09–33.74, I2 = 99.00%, Supplementary Figs. 18) and 46.03% (95% CI 38.81–53.34, I2 = 99.48%, Supplementary Fig. 19). The subgroup analysis and risk factor analysis for these symptoms were listed in Supplementary Tables 10–15, respectively.

Grading of recommendations, Assessment, Development and evaluations (GRADE) quality of evidence

The certainty of evidence for different menopausal symptoms (very low) were assessed using the GRADE framework. The results of this assessment are shown in Supplementary Table 16.

Discussion

This was the first and largest systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the global prevalence of menopause-related symptoms among middle-aged women from multiple domains involving somatic, psychological, urogenital and others symptoms. The meta-analysis found that the prevalence of these symptoms varies considerably, with the highest prevalence of joint and muscular discomfort (65.43%, 95% CI 62.51–68.29) and lowest of formication (20.5%, 95% CI 13.44–28.60). Menopausal symptom epidemiology was significantly influenced by factors such as countries, continents, country development, country income level and diagnostic tools. Furthermore, it was shown that the prevalence of most symptoms in postmenopausal stage increased dramatically. Additionally, a noteworthy distinction was observed between BMI and sleep problems, depression, anxiety and urinary problems.

Menopause is characterized by vasomotor symptoms, which include hot flashes, perspiration, and occasionally shaking and a cold feeling. Because of their abrupt and seemingly random onset throughout the day or even at night, these are usually the most common and irritating menopausal symptoms. Vasomotor symptoms can start up to two years before to the final menstrual period (FMP), peak one year following the FMP, and last for four years in about half of the female population. The multiethnic, community-based Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) [33–35] reported that vasomotor symptoms were more prevalent among African-American and Hispanic women and less prevalent among Japanese-American and Chinese-American women than white women. As the most important vasomotor symptom, emerging analyses of studies revealed that the prevalence of hot flashes in Asian women is similar to those of Western countries [36, 37]. As a result, the current study’s pooled estimates of different continents find that women in Africa with highest prevalence of hot flashes, whereas women in Asia, Europe, and North America are of comparable prevalence, which validates prior studies [33–35]. Besides, our result found the prevalence of sleeping problems (51.89%, 95% CI 49.55–54.22) are similar to pooled estimates of a previous meta-analysis (51.6%, 95% CI 44.6–58.5) [13]. Six out of ten middle-aged women reported having joint and muscular discomfort, which was the most common somatic symptom. The idea that a decline in ovarian function may have a direct detrimental impact on muscle and joint tissue stems from the fact that these tissues have estrogen receptors (ERs) [38, 39]. Importantly, pooled prevalence estimates show that, with the exception of headache, all somatic domain complaints are more common in the perimenopause and postmenopause than in the premenopause. According to community-based studies, women’s migraine headache prevalence has been shown to rise throughout the perimenopause and fall during the postmenopause [40, 41]. This study found a similar tendency, albeit it was not statistically significant. It’s interesting to note that women who have abnormal weight—that is, underweight, overweight, or obese—are more likely to experience sleep problems. This finding is in line with a study by Prather et al. that discovered a link between sleep disturbance and obesity or overweight [42]. The worrying trend of rising obesity rates among postmenopausal women globally necessitates further attention [43–45].

Menopause can be psychologically distressing for women. The global prevalence of depression among middle-aged women was found to be approximately 43.34% with equally matched prevalence of study from global perspective [46]. Furthermore, current findings revealed strong correlation between the prevalence of depression among middle-aged women with country development. This is in line with previous research, which has shown that middle-aged women from developing countries have a higher prevalence of depression. This could be explained by governments from developed countries have greater beneficial and supportive policies for public health [47]. In contrast, middle-aged women were disadvantaged in healthcare and living conditions, which in turn predisposed them to depression. Different from somatic symptoms, only exhaustion and depression in psychological domain are related to menopausal stage, with climbing prevalence from premenopausal to postmenopausal stage, while anxiety, irritability and mood swings have no statistical difference. Consistent with other studies [46, 48], irritability levels in our study rise throughout menopause and diminish following menopause, though not statistically significant. While other research [10, 49–52] revealed a tenuous connection between depression and being overweight or obese, our investigation showed that these conditions raise the risk of depression in middle-aged women.

Interestingly, the prevalence of symptoms in urogenital domain is similar across countries with different status of development where middle-aged women from, which indicates minimal relationship between develop status of countries and urogenital symptoms among middle-aged women. Although they are not frequently reported, urogenital symptoms are often present after menopause [53]. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have reported that the menopausal transition is associated with urogenital symptoms, independent of aging [54]. Our findings are in line with previous research that prevalence of urogenital problems is sharp rise across menopausal stage (p < 0.01), but a weaker correlation with age (p = 0.69, 0.19, 0.08 for sexual problems, vagina dryness, and urinary problems, respectively). Pastore, et al [55] found that overweight seems to be linked with a two to four folds higher incidence of urogenital symptoms in women with normal weight. Current study is consistent with it that overweight or obesity are found to be important correlates of urinary problems.

Greendale et al. [56]. discovered an intriguing circumstance: women going through the perimenopausal stage of the transition frequently report experiencing a decrease in memory and focus. The current study also discovered, while not statistically significantly, that middle-aged women going through the perimenopausal stage are more likely to experience memory loss and concentration problems. More precisely, as compared to the premenopausal and postmenopausal stages, the perimenopausal stages were found to have deficiencies in processing speed and a lack of progress in verbal memory with repeated testing [56]. These findings imply that the negative impact of menopause on cognitive function is only present during the perimenopausal phase. Given that anatomical studies have shown that the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which govern episodic and working memory, display high amounts of ERs, it is thought that estradiol plays a significant role in cognitive performance [57]. Thus, the transitory cognitive abnormalities reported clinically at this time may be caused by fluctuating levels of estrogen during perimenopause [57].

There are strengths of this meta-analysis which included the largest population-based study to-date, inclusion of nineteen symptoms from multiple domains for a more comprehensive understanding of menopause and use of subgroup analysis to pool estimates of risk factors with improved accuracy compared with findings from a single study. However, several limitations should be noted. First, the heterogeneity between studies remains unexplained by the variables studied. Variations in study sample size and representativeness contribute significantly to the heterogeneity of the prevalence. Second, data based on participants’ self-reports can result in reporting bias. Third, most research focused on cross-sectional studies creates recall bias. Fourth, significant lack of articles from countries with low-income level. Finally, GRADE approach indicated our results with a suboptimal quality of evidence. Therefore, higher-quality research is needed in the future to clarify the conclusions.

Conclusions

Women typically spend about 30% of their lifespan around the menopause. Our study indicated that most menopause-related symptoms affected 50% middle-aged women. Thus, it is important to ensure women and health professionals understand the perimenopause transition, its symptoms and treatments and create a more positive view to the menopause. Health-care providers caring for women at all levels of the healthcare system must be well prepared to guide women through this transition and provide advice to improve quality of life.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Y.F., F.L., K.L and Z.L., designed the study and performed the data review and extraction. X.Z., L.C., Y.L., L.Y., X.Z., provided technique assistance for data analysis and providing feedback for the manuscript. J.L. and Q.F. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of results and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the fellowship of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M702340), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82070625, 82070846), the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2020YJ0237, 2021YFS0230, 2020YFS0573, 2021ZYCD016, 2022NSFSC1441), Key Research and Development Program of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2019YFS0360), the 135 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18003, ZYJC18025, 2016105 and ZYGD20006), Program for Oversea High-Level Talents Introduction of Sichuan Province of China (21RCYJ0046).

Data availability

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yiqiao Fang and Fen Liu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Kewei Li, Email: vivian5225133@outlook.com.

Zhihui Li, Email: rockoliver@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1.Maric-Bilkan C, Gilbert EL, Ryan MJ. Impact of ovarian function on cardiovascular health in women: focus on hypertension. Int J Women’s Health. 2014;6:131–9. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S38084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauley JA. Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids, 2015. 99(Pt A): pp. 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Talaulikar V. Menopause transition: physiology and symptoms. Best Practice & Research. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;81:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis SR, et al. Menopause-Biology, consequences, supportive care, and therapeutic options. Cell. 2023;186(19):4038–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monteleone P, et al. Symptoms of menopause - global prevalence, physiology and implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):199–215. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harlow SD, et al. Executive summary of the stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Volume 19. Menopause (New York, N.Y.),; 2012. pp. 387–95. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Avis NE, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):531–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palacios S, et al. Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric: J Int Menopause Soc. 2010;13(5):419–28. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.507886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polisseni AF, et al. [Depression and anxiety in menopausal women: associated factors] Revista Brasileira De Ginecol E Obstetricia: Revista Da Federacao Brasileira Das Sociedades De Ginecol E Obstet. 2009;31(3):117–23. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032009000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlawat P, et al. Prevalence of Depression and its Association with Sociodemographic Factors in Postmenopausal Women in an urban resettlement colony of Delhi. J Mid-life Health. 2019;10(1):33–6. doi: 10.4103/jmh.JMH_66_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R-X, et al. Perimenopausal syndrome and mood disorders in perimenopause: prevalence, severity, relationships, and risk factors. Medicine. 2016;95(32):e4466. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav V, et al. A meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2021;57:102581. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salari N, et al. Global prevalence of sleep disorders during menopause: a meta-analysis. Volume 27. Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung; 2023. pp. 1883–97. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Parker G et al. Technical report for SCIE research review on the prevalence and incidence of parental mental health problems and the detection, screening and reporting of parental mental health problems. York: Social Policy Research Unit, University of York, 2008.

- 15.Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 1995. 854. [PubMed]

- 16.Chedraui P, et al. Application of the 10-item Cervantes Scale among mid-aged Ecuadorian women for the assessment of menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. 2014;79(1):100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikeda H, et al. Effects of Candesartan for middle-aged and elderly women with hypertension and menopausal-like symptoms. Hypertens Research: Official J Japanese Soc Hypertens. 2006;29(12):1007–12. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alder E. The Blatt-Kupperman menopausal index: a critique. Maturitas. 1998;29(1):19–24. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heinemann LAJ, Potthoff P, Schneider HPG. International versions of the Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:p28. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokota M, et al. Symptoms and effects of physical factors in Japanese middle-aged women. Menopause (New York N Y) 2016;23(9):974–83. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis JE, Hilditch JR, Wong CJ. Further psychometric property development of the menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire and development of a modified version, MENQOL-Intervention questionnaire. Maturitas. 2005;50(3):209–21. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter MS, Liao KL. A psychological analysis of menopausal hot flushes. Br J Clin Psychol. 1995;34(4):589–99. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1995.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter MS. The Women’s Health Questionnaire (WHQ): Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2003. 1: p. 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Hilditch JR, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 2008;61(1–2):107–21. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee Y, et al. Development of the Taiwanese Depression Questionnaire. Chang Gung Med J. 2000;23(11):688–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zung WW, A SELF-RATING DEPRESSION, SCALE Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck AT, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carleton RN, et al. The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: a review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bech P, et al. Quantitative rating of depressive states. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1975;51(3):161–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1975.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasconcelos-Raposo J, et al. Factor structure and normative data of the Greene Climacteric Scale among postmenopausal Portuguese women. Maturitas. 2012;72(3):256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The female sexual function index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther, 2005. 31(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kravitz HM, et al. Sleep difficulty in women at midlife: a community survey of sleep and the menopausal transition. Menopause (New York N Y) 2003;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kravitz HM, Joffe H. Sleep during the perimenopause: a SWAN story. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2011;38(3):567–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koch J. Primed in situ labeling as a fast and sensitive method for the detection of specific DNA sequences in chromosomes and nuclei. Methods (San Diego Calif) 1996;9(1):122–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Islam RM et al. Vasomotor symptoms in women in Asia appear comparable with women in western countries: a systematic review. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 2017. 24(11): p. 1313–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Sriprasert I, et al. An International Menopause Society study of vasomotor symptoms in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Thailand. Climacteric: J Int Menopause Soc. 2017;20(2):171–7. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2017.1284782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiik A, et al. Expression of both oestrogen receptor alpha and beta in human skeletal muscle tissue. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131(2):181–9. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0512-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roman-Blas JA, et al. Osteoarthritis associated with estrogen deficiency. Arthritis Res Therapy. 2009;11(5):241. doi: 10.1186/ar2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freeman EW, et al. Symptoms in the menopausal transition: hormone and behavioral correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):127–36. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000295867.06184.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin VT, et al. Perimenopause and Menopause are Associated with high frequency headache in women with migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache. 2016;56(2):292–305. doi: 10.1111/head.12763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prather AA, et al. Poor sleep quality potentiates stress-induced cytokine reactivity in postmenopausal women with high visceral abdominal adiposity. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;35:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]