Abstract

A highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV), SHIVDH12R, isolated from a rhesus macaque that had been treated with anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibody at the time of primary infection with the nonpathogenic, molecularly cloned SHIVDH12, induced marked and rapid CD4+ T cell loss in all rhesus macaques intravenously inoculated with 1.0 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) to 4.1 × 105 TCID50s of virus. Animals inoculated with 650 TCID50s of SHIVDH12R or more experienced irreversible CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion and developed clinical disease requiring euthanasia between weeks 12 and 23 postinfection. In contrast, the CD4+ T-cell numbers in four of five monkeys receiving 25 TCID50s of SHIVDH12R or less stabilized at low levels, and these surviving animals produced antibodies capable of neutralizing SHIVDH12R. In the fifth monkey, no recovery from the CD4+ T cell decline occurred, and the animal had to be euthanized. Viral RNA levels, subsequent to the initial peak of infection but not at peak viremia, correlated with the virus inoculum size and the eventual clinical course. Both initial infection rate constants, k, and decay constants, d, were determined, but only the latter were statistically correlated to clinical outcome. The attenuating effects of reduced inoculum size were also observed when virus was inoculated by the mucosal route. Because the uncloned SHIVDH12R stock possessed the genetic properties of a lentivirus quasispecies, we were able to assess the evolution of the input virus swarm in animals surviving the acute infection by monitoring the emergence of neutralization escape viral variants.

Over the past decade, simian/human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric viruses (SHIVs) have been constructed containing various amounts of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) sequence and exhibiting a continuum of disease-inducing phenotypes (10, 28, 29, 34, 35). Because early studies (14, 34; our unpublished work) had indicated that SIV gag and pol sequences were required for high levels of SHIV production in cultured macaque peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), our initial strategy was to generate chimeric viruses containing as much HIV-1 genetic information as possible. The first chimeric virus we evaluated, SHIVMD1, contained intact tat, rev, vpu, env, and nef genes from the dual-tropic primary HIV-1DH12 isolate and a vpr gene of mixed origin (SIVmac239, HIV-1NL4-3, and HIV-1DH12) (35). SHIVMD1 infections were readily established in rhesus monkeys, pig-tailed macaques, and cynomolgus monkeys, but only 1 of the 21 inoculated animals developed immunodeficiency. Since our goal was to generate a pathogenic SHIV for use in vaccine experiments, a “second-generation” SHIVDH12 (previously designated SHIVMD14) was created in which the HIV-1 nef gene was replaced with the SIVmac239 nef gene. SHIVDH12, in fact, replicated to high titers and induced disease in pig-tailed monkeys (35). However, although SHIVDH12 infections were readily established in more than 15 rhesus monkeys, virus loads were generally low, and none of the inoculated animals suffered CD4+ T cell depletions or any signs of disease.

Pathogenic SHIVs, which cause rapid CD4+ T lymphocyte depletions within weeks of inoculation, have been generated as a result of serial animal-to-animal passage of whole blood and bone marrow from macaques initially infected with nonpathogenic chimeric viruses (10, 28). We recently reported the isolation of the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R, which arose during a single in vivo passage in a rhesus monkey treated with an anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibody at the time of its primary infection with the nonpathogenic SHIVDH12 (8). A tissue culture-derived stock of SHIVDH12R induced marked and rapid CD4+ T cell loss following intravenous inoculation of rhesus monkeys. Although SHIVDH12R retained its capacity to utilize both CCR5 and CXCR4 as coreceptors during virus entry, it could no longer be neutralized by antibodies targeting glycoprotein 120 (gp120) epitopes associated with its nonpathogenic SHIVDH12 parent (8). The latter result was consistent with nucleotide sequence analyses of 22 independent PCR clones, amplified from the SHIVDH12R-infected cells, which revealed changes affecting gp120 (13 amino acid) and gp41 (6 amino acid), accompanying the acquisition of increased virulence. Furthermore, the uncloned SHIVDH12R tissue culture-derived stock possessed the genetic properties of a lentivirus quasispecies because of the presence of additional, but common, gp120 amino acid substitutions in some of the 22 PCR clones.

We previously reported that although SHIVDH12R induces an extremely rapid and profound depletion of CD4+ T cells in all infected rhesus monkeys, the loss of this T-cell subset did not appear to be irreversible in animals inoculated with small amounts of virus (8). This observation was systematically examined by performing a rigorous in vivo virus titration and various routes of inoculation. Our results show that macaques that were administered large intravenous SHIVDH12R inocula experienced a rapid and unremitting downhill clinical course. In contrast, rhesus monkeys receiving 25 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) or less of virus survived the primary infection with markedly reduced but stable levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes and produced antibodies capable of neutralizing SHIVDH12R. The animal-specific evolution of the SHIVDH12R quasispecies in surviving macaques was monitored by the emergence of neutralization escape viral variants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The source and preparation of the tissue culture-derived SHIVDH12R stock has been previously described (8). It had a titer of 1.6 × 105 TCID50/ml measured in rhesus monkey PBMC and 4.1 × 105 TCID50/ml measured in MT4 cells.

Animals, virus inoculation, and sample collection.

The 14 rhesus macaques listed in Table 1 were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2). They were housed in a biosafety level 2 facility; biosafety level 3 practices were followed. Phlebotomies and virus inoculations were performed with animals anesthetized with tiletamine-HCl and zolazepam-HCl (Telazol; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, Iowa). EDTA-treated blood specimens were used for lymphocyte phenotyping analysis and complete blood counts; acid citrate-dextrose-A-treated samples of blood were used to prepare plasma and PBMC.

TABLE 1.

Profile of animals used in this study

| Animal ID | Inoculum size | Route of inoculation | Infection | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H27 | 4 × 105 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Died at 12.6 wks PIb |

| H358 | 4 × 105 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Died at 13.0 wks PI |

| 5980 | 16,400 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Died at 21.3 wks PI |

| 5981 | 656 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Died at 23.1 wks PI |

| 6071 | 25 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Healthy |

| H520a | 25 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Healthy |

| H521a | 5 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Died at 24.1 wks PI |

| 6049 | 5 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Healthy |

| 6074 | 1 TCID50 | Intravenous | + | Healthy |

| H431 | 1 TCID50 | Intravenous | − | No infection established |

| H520a | 0.2 TCID50 | Intravenous | − | No infection established |

| H521a | 0.04 TCID50 | Intravenous | − | No infection established |

| H704 | 1 × 105 TCID50 (3 times) | Intravaginal infusion | + | Healthy |

| 903a | 1 × 105 TCID50 (3 times) | Intravaginal infusion | − | No infection established |

| H385 | 5 × 104 TCID50 | Intravaginal infusion | + | Healthy |

| T14 | 100 TCID50 | Intrarectal injection | + | Died at 12.0 wks PI |

| 903a | 100 TCID50 | Intrarectal injection | + | Healthy |

If no infection was established, this animal was reinoculated with a larger dose or via an alternative route following 24 weeks of observation.

PI, postinfection.

Lymphocyte phenotyping.

EDTA-treated blood samples were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC] [Serotec, Raleigh, N.C.], CD4-allophycocyanin, CD8-peridinin chlorophyll protein, and CD20-phycoerythrin [Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.]) and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSort; Becton Dickinson) as previously described (8, 35).

Quantitation of plasma viral RNA levels.

Plasma viral RNA levels were determined by real-time PCR (ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) as previously described, using reverse-transcribed viral RNA in plasma samples from SHIVDH12R-infected macaques (8). The cDNA was amplified (45 cycles/default setting) with Ampli Taq Gold DNA polymerase (PCR core reagents kit; Perkin-Elmer/Roche) with primer pairs corresponding to SIVmac239 gag gene sequences (forward, nucleotides 1181 to 1208, and reverse, nucleotides 1338 to 1317) present in SHIVDH12R. Plasma from SHIVDH12R-infected macaques and SHIVDH12-infected rhesus PBMC culture supernatants, previously quantitated by the branched DNA method (4), served as standards for the reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay.

Western blot analysis.

For immunoblotting, SHIVDH12 particles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, mixed with gp120 expressed from a recombinant vaccinia virus, and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer as previously described (8). The viral proteins were electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.), and incubated with serially collected plasma samples (diluted 1:100). The membranes were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.) and viral protein-specific bands were visualized on X-ray film using a chemiluminescent reagent (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate; Pierce).

Virus neutralization assays.

The titers of virus-specific neutralizing antibody in samples of plasma were determined by a previously described limiting-dilution endpoint assay, which measures 100% neutralization against 100 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, SHIVDH12, or SHIVDH12R(W30) (8, 33, 40). Neutralization antibody titers were calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (27).

Mathematical analysis.

The early kinetics of an in vivo virus infection can be described by the exponential function V = V0exp[k(t − tc)], where V is the concentration of virus particles in the blood, V0 is the virus concentration after the first cycle of virus infection at t = tc, tc being the time to complete a single cycle of infection, and k is the infection rate constant as previously defined for HIV-1 infections in cultured cells (5). Using this formula, one can derive an approximate relationship between the time required to reach the peak of virus infection, tp, and the input SHIVDH12R TCID50:

|

1 |

where N is the number of susceptible target cells and it is assumed that (i) the input TCID50 equals the initial number of infected cells and (ii) the number of virus particles in the plasma is proportional to the number of virus-producing cells. The average k for the nine monkeys inoculated intravenously with SHIVDH12R was calculated by a linear regression analysis of the dependence of tp versus ln(TCID50) (see Fig. 2C) using the Scientist (MicroMath, Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah) software program. The infection rate constants for individual SHIVDH12R-infected rhesus monkeys were calculated separately by a linear regression analysis of the dependence of ln(V) versus t, using the same software. The initial infection rate constants were also estimated using the formula:

|

2 |

where V2 and V1 are the first two measurable virus concentrations at times t2 and t1, respectively. The same formula was used to estimate the virus decline rate constants, d, with V1 being the peak virus concentration at time t1 and V2 being the virus concentration at time t2 (equal to 2 weeks postinfection peak). Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica software program (Statsoft, Tulsa, Okla.).

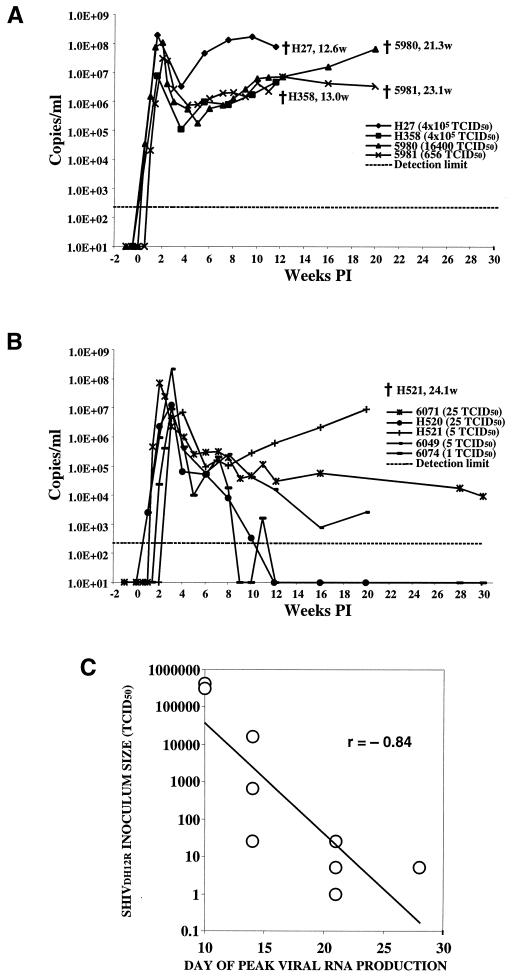

FIG. 2.

Viral RNA levels in rhesus macaques inoculated intravenously with SHIVDH12R. Samples of plasma collected at the indicated times from animals infected with 650 TCID50 or more (A) or 25 TCID50 or less (B) of SHIVDH12R were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for viral RNA using primer pairs mapping to SIV gag sequences. The detection limit, approximately 200 RNA copy equivalents/ml, is indicated by the dashed line. The time (weeks postinfection [PI]) of death is indicated. (C) Relationship of the input inoculum to the time of peak virus production. The correlation coefficient is indicated.

RESULTS

Titration of SHIVDH12R infectivity in vivo.

In the initial study describing the origin of the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R, we reported that rhesus macaques inoculated with 4 × 105 or 6.5 × 102 TCID50 (determined for MT4 cells) of virus became infected and experienced a rapid and irreversible decline of circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes (8). To ascertain the infectivity and pathogenicity of the SHIVDH12R virus stock administered intravenously to rhesus monkeys, a standard limiting-dilution titration approach was used (Table 1). Three of the animals (H431, H520, and H521), inoculated with 1.0, 0.2, and 0.04 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, respectively, did not become infected (no detectable PBMC-associated proviral DNA, p27 antigenemia, or virus-specific antibody responses through 24 weeks postinfection [data not shown]). Because they remained uninfected, rhesus monkeys H520 and H521 were reused to obtain a solid titration endpoint and were intravenously inoculated with 25 and 5 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, respectively. Table 1 indicates that one of the two monkeys exposed to 1 TCID50 and all animals injected with larger virus inocula became infected. In this titration, the 50% animal infectious dose of SHIVDH12R corresponded to approximately 1 TCID50.

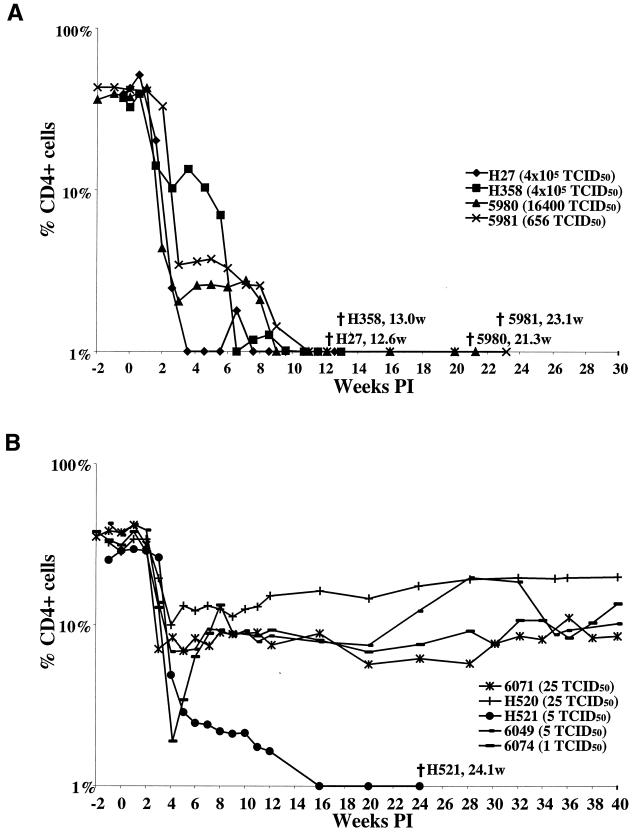

Levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes in rhesus monkeys intravenously inoculated with different amounts of SHIVDH12R.

Every animal that became infected with SHIVDH12R administered intravenously suffered a profound and rapid depletion of circulating CD4+ T cells within 2 to 3 weeks of inoculation. The CD4+ T lymphocyte numbers declined irreversibly to below 50 cells/μl by weeks 3.6 to 7.6 postinfection in the four monkeys (H27, H358, 5980, and 5981) receiving the largest amounts (6.5 × 102 to 4.1 × 105 TCID50) of virus (Fig. 1A). In addition, the monkeys which received 25 TCID50 or less of SHIVDH12R also experienced rapid and marked CD4+ T cell loss. However, in contrast to irreversible CD4+ T cell depletions observed in animals inoculated with the larger amounts of virus, the percent CD4+ cells never fell below 2%, with the exception of monkey H521 (Fig. 1B). In three of these four animals, the CD4+ T-cell number remained quite low (100 to 300 cells/μl) compared to their preinoculation levels at nearly 1 year postinoculation; the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes in monkey H520 was somewhat higher. One of the five rhesus monkeys (H521), which received only 5 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, did experience a precipitous loss of CD4+ T cells, which fell to 44 cells/μl by 12 weeks postinfection.

FIG. 1.

CD4+ T lymphocyte levels in rhesus macaques inoculated intravenously with SHIVDH12R. Samples of blood collected at the indicated times from animals infected with 650 TCID50 or more (A) or 25 TCID50 or less (B) of SHIVDH12R were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in Materials and Methods. The time (weeks postinoculation [PI]) of death is indicated.

Plasma viral RNA levels in SHIVDH12R-infected rhesus monkeys.

All animals infected intravenously with SHIVDH12R rapidly developed high plasma viral RNA loads (Fig. 2). The initial peaks of viral RNA production occurred between weeks 1.6 and 4 and ranged from 7 × 106 to 2 × 108 RNA copies/ml of plasma. There was no correlation between inoculum size and peak virus loads. However, the kinetics of reaching the initial peak of plasma viremia appeared to be related to the amount of virus administered (Fig. 2C). A linear regression analysis of the dependence of the time required to reach the infection peak, tp, versus the natural logarithm of the input inoculum size, ln(TCID50), suggested that the average infection rate constant, k, for the nine monkeys inoculated with SHIVDH12R intravenously is equal to 1.06 day−1 (R = 0.81; P = 0.0081; n = 9). Individual infection rate constants, k, were also determined for five of the SHIVDH12R-infected macaques for which multiple “prepeak” plasma samples had been collected. The k values for these animals were 5980 (1.34; 1.27), 5981 (1.03; 1.24), 6074 (0.85; 0.95), 6049 (0.81; 0.84), and H520 (0.61; 0.98), where the numbers in parentheses denote the infection rate constants in day−1 calculated by using either all measurable time points, including the infection peak, or the first two measurable points, respectively (equation 2, Materials and Methods). Although a trend emerged suggesting a correlation between high initial infection rate constants and progression to fatal disease (animals 5980 and 5981, which had to be euthanized, compared to surviving and asymptomatic animals 6074, 6049, and H520), this correlation did not reach the level of statistical significance (Spearman correlation, R = 0.87 and P = 0.058; Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.083 and n = 5). However, the effective rate decline constants, d, characterizing virus decay during the first two weeks after the infection peak were statistically significantly correlated to clinical outcome (Spearman correlation, R = 0.78 and P = 0.01; Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.027 and n = 9); higher rate constants corresponded to greater survival.

By 4 to 6 weeks postinfection, the SHIVDH12R loads had decreased to 105 to 106 RNA copies/ml in all of the infected animals. However, the plasma viral RNA levels in monkeys inoculated with 650 TCID50 or more of virus (Fig. 2A) subsequently rose a second time and were accompanied by clinical disease (see below). This pattern is to be contrasted with that observed for the animals inoculated with 25 TCID50 or less of SHIVDH12R (Fig. 2B), in which the RNA loads continued to fall, reaching levels of 103 to 104 RNA copies/ml (macaques 6071 and 6049) or became undetectable (macaques H520 and 6074). However, PBMC-associated proviral DNA remained measurable in these latter two animals throughout the study, ranging from 820 to 6,500 copies/105 CD4+ T cells in macaque H520 and from 22 to 120 copies/105 CD4+ T cells in monkey 6074. As noted above, rhesus monkey H521 was the exception among the “low inoculum” group of animals. This macaque experienced a second sustained wave of high viremia (Fig. 2B) and was euthanized at week 24 postinfection.

The clinical course of SHIVDH12R infection in macaques correlates with inoculum size.

Not unexpectedly, the pattern of CD4+ T cell decline (and inoculum size) was predictive of clinical outcome. The four animals receiving 650 TCID50 or more of virus intravenously developed disease and were euthanized between weeks 12 and 23, whereas four of the five monkeys administered 25 TCID50 or less remained alive, with CD4+ T lymphocyte counts that leveled off at the 100-to-500-cells/μl range (Table 1; Fig. 1). The two rhesus monkeys (H27 and H358) receiving the largest (4.1 × 105 TCID50) SHIVDH12R inoculum both developed anorexia within 1 to 2 weeks of infection and, because of intractable diarrhea and marked weight loss, were euthanized at weeks 12 and 13, respectively. An autopsy of animal H27 revealed multifocal interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, which was associated with infiltrating multinucleated cells. Macaque 5981, originally inoculated with 650 TCID50, experienced a somewhat slower but irreversible CD4+ T lymphocyte decline (1,230 cells/μl preinfection; 142 cells/μl at week 3; 10 cells/μl at week 9) and was euthanized at week 23 because of protracted diarrhea and deteriorating clinical status. A necropsy revealed a multifocal Candida albicans infection of the esophagus and interstitial pneumonia with numerous giant cells. As noted earlier, animal H521 was the outlier among the rhesus monkeys receiving the small amounts of the SHIVDH12R inoculum. This animal developed anorexia at week 18 and diarrhea at week 23 and was euthanized at week 24 with a CD4+ T cell count of 2 cells/μl of blood.

It is worth noting that the absolute levels of peak viral RNA production did not correlate with the clinical outcome (Fig. 2). Animals H521 and H358 had peak virus loads of only 7 × 106 to 8 × 106 RNA copies/ml and experienced irreversible CD4+ T cell decline and death, while monkey 6049 produced 2 × 108 RNA copies/ml yet had a partial recovery of its CD4+ T cell numbers and an asymptomatic clinical course.

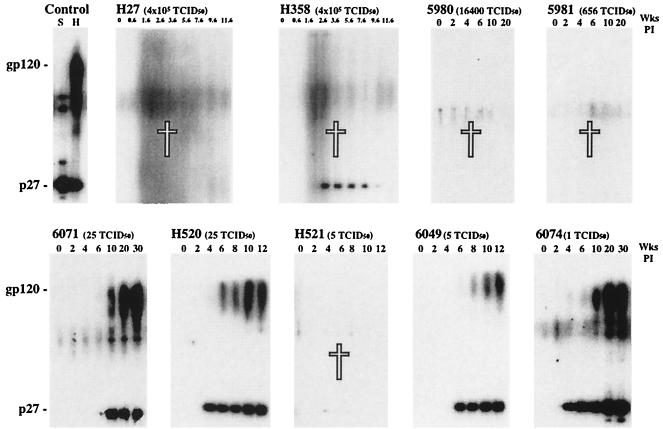

The humoral responses of rhesus monkeys intravenously inoculated with SHIVDH12R.

Virus-specific antibodies elicited in SHIVDH12R-infected animals were initially evaluated by immunoblot analysis. The four animals which received the large virus inocula and suffered irreversible CD4+ T cell depletion also failed to make anti-gp120 antibodies (Fig. 3, top row). Animal H358, however, which was exposed to 4.1 × 105 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, transiently produced low levels of anti-p27 (CA) antibody between weeks 2 and 8, which became undetectable at the time it was euthanized at week 13. As expected, four of the five rhesus monkeys, which had been inoculated with small amounts of virus and did not suffer a complete loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes, produced high titers of anti-Gag (SIV) and -Env (HIV-1) antibodies (Fig. 3, bottom row). Animal H521, a recipient of only 5 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, was the exception and, during its downhill clinical course, produced no detectable antibodies.

FIG. 3.

Humoral immune responses in rhesus macaques inoculated intravenously with SHIVDH12R. Plasma samples collected at the indicated times from nine monkeys were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods. Plasma from a SIVmac239-infected pig-tailed macaque (S) and an HIV-1DH12-infected chimpanzee (H) served as positive controls. The white crosses indicate animals that died.

We previously reported that neutralization of primate lentiviruses bearing the DH12 family of envelope glycoproteins (viz. HIV-1DH12 and SHIVDH12) can be readily demonstrated by limiting-dilution assays utilizing reverse transcriptase production as the readout (7, 33, 40). The neutralizing activities elicited during chronic HIV-1DH12 infections of chimpanzees or SHIVDH12 infections of macaques have been shown to be directed against the viral gp120 envelope glycoprotein (1, 36, 40). Rhesus monkeys chronically infected with the nonpathogenic SHIVDH12 typically develop virus neutralization titers specific for SHIVDH12 which range from 1:18 to 1:93 (7).

When plasma samples from animals inoculated with the large amounts of SHIVDH12R were evaluated for neutralizing antibodies, no activity was detected (Table 2). This result was consistent with the absence of anti-gp120 humoral responses, as measured by immunoblotting, in these same animals, with few or no detectable circulating CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3). This result was also true for macaque H358, which had transiently produced anti-p27 but no anti-gp120 antibodies between weeks 2 and 8 postinfection (Fig. 3). In contrast, the low inoculum group of infected animals, again with the exception of monkey H521, all generated antibodies capable of neutralizing the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R (Table 2). The neutralization titers measured in these monkeys fell in a range previously reported for SHIV-infected rhesus macaques with the endpoint dilution assay (7).

TABLE 2.

Titers of neutralizing antibody to SHIVDH12R

| Plasma sample taken at: | Titer for subject (inoculum size)a:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H27 (4 × 105 TCID50) | H358 (4 × 105 TCID50) | 5980 (16,400 TCID50) | 5981 (656 TCID50) | 6071 (25 TCID50) | H520 (25 TCID50) | H521 (5 TCID50) | 6049 (5 TCID50) | 6074 (1 TCID50) | |

| Preinfection | <1.9 | <1.9 | <0.8 | <0.8 | <0.8 | <3.1 | <3.1 | <3.1 | <0.8 |

| 10 wks | <1.9 | <1.9 | <0.8 | <0.8 | <0.8 | 16.0 | <3.1 | <3.1 | <0.8 |

| 20 wks | — | — | <0.8 | <0.8 | 3.9 | 21.0 | <1.6 | 7.0 | 11.1 |

| 30 wks | — | — | 11.6 | 21.0 | — | 63.1 | 12.7 | ||

| 40 wks | 7.0 | 43.7 | 75.8 | 8.4 | |||||

| 50 wks | 4.9 | ND | ND | 7.0 | |||||

| 60 wks | 7.0 | ND | ND | 8.4 | |||||

| 70 wks | 8.4 | ND | ND | 8.4 | |||||

ND, not done; —, animal died.

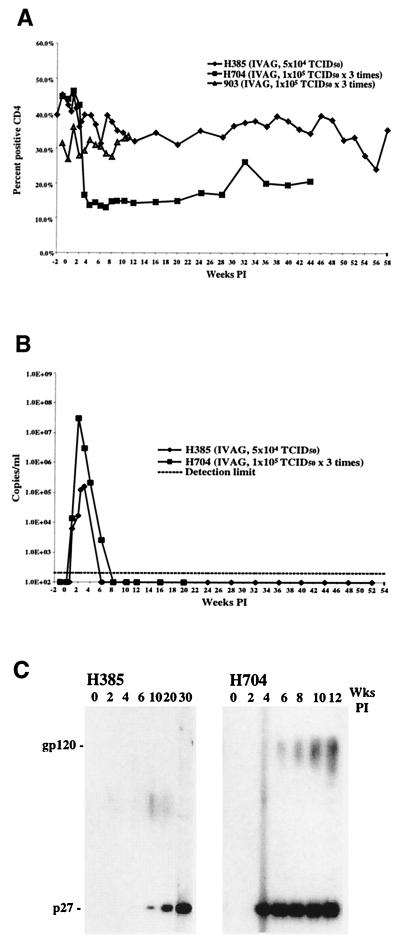

Infection of rhesus monkeys with SHIVDH12R by intravaginal infusion.

In experiments modeling mucosal transmission of HIV-1 in humans, macaques have been successfully challenged with SIV and SHIVs by the vaginal and rectal routes of inoculation (6, 17, 23). To ascertain whether rhesus monkeys could be infected and develop immunodeficiency following exposure to the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R through a mucosal portal of entry, 5 × 104 TCID50 of virus was administered by a single atraumatic intravaginal infusion to three female rhesus monkeys (H704, 903, and H385). Only one (H385) of the three animals became infected; p27 antigenemia, DNA PCR, and virus-specific antibody responses (analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and immunoblotting) were not detectable in the other two monkeys during a 12-week observation period. Macaques H704 and 903 were subsequently rechallenged with SHIVDH12R by intravaginal infusion (5 × 104 TCID50 administered on three separate occasions over a 96-h period). Only animal H704 became infected following this rechallenge; monkey 903 remained proviral DNA negative over the ensuing 12-week observation period and did not produce virus-specific antibodies.

Although two of the three animals exposed to SHIVDH12R became infected as a result of intravaginal infusion, their clinical courses differed markedly from those of animals inoculated intravenously. Rhesus monkey H704 suffered a significant CD4+ T lymphocyte decline beginning 3 weeks postinfection, with numbers falling to a low of 189 cells/μl of blood at week 7 (Fig. 4A). At present, the CD4+ T-cell numbers in macaque H704 have risen to approximately 50% of the preinfection level. This response is similar to that observed for animals administered small SHIVDH12R inocula intravenously. Macaque H385, on the other hand, experienced no acute or long-term CD4+ T cell decline. Both animals also exhibited patterns of viral RNA synthesis not seen in monkeys inoculated by the intravenous route (Fig. 4B). Monkey H385 produced the lowest peak viral RNA levels (1.5 × 105 copies/ml at week 4) ever measured in a SHIVDH12R-infected macaque, with viral RNA becoming undetectable at week 6 postinfection. Although rhesus monkey H704 developed a peak viral RNA load (5.4 × 107 copies/ml) comparable to that observed in animals inoculated intravenously with SHIVDH12R, its viremia rapidly cleared and could not be measured at 8 weeks postinfection. Results of an immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4C) using plasma from these two infected macaques were consistent with the plasma viral RNA levels. Antibodies directed against both p27 and gp120 rapidly appeared in monkey H704, whereas only a delayed anti-p27 response occurred in animal H385. Interestingly, no antibodies capable of neutralizing SHIVDH12R were detected in either animal (through week 70 for H385 and week 40 for H704) infected by intravaginal infusion (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

The dynamics of CD4+ T lymphocyte (A), viral RNA (B), and antibody (C) levels in rhesus macaques following atraumatic intravaginal infusion of SHIVDH12R.

Infection of rhesus monkeys with SHIVDH12R by a nonintravenous parenteral route.

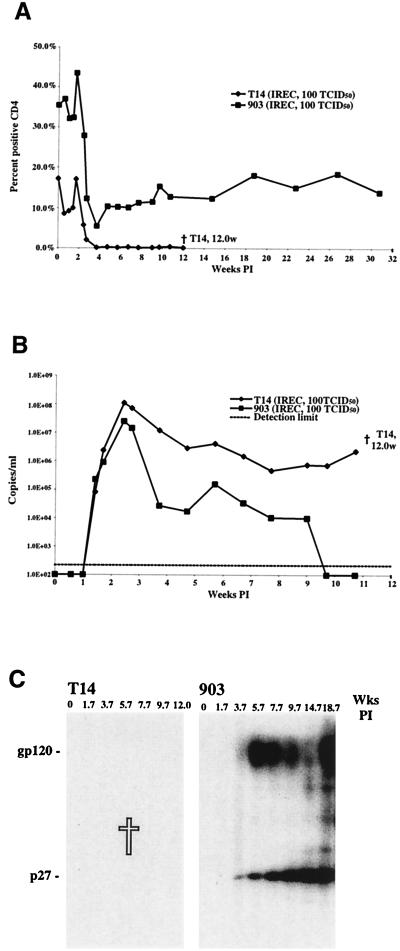

The relative resistance of rhesus monkeys to the SHIVDH12R vaginal mucosal challenge is consistent with studies indicating that larger inoculum amounts are required to establish SIV infections in macaques when nonintravenous routes of inoculation are used (18, 20). It is worth noting, however, that most natural retroviral infections in nonhuman species (e.g., mice, cats, and monkeys) arise as a result of fighting (biting and scratching) or transmission through breast milk to newborn animals (9, 13, 41). Nonetheless, mucosal routes of inoculation have been used in nonhuman primates to model sexual transmission of HIV-1 in humans or, in some vaccine efficacy experiments, to reduce the immediate and systemic virus dissemination attending intravenous administration of a challenge virus. Because earlier studies have, in fact, demonstrated that lymphocytes, rather than epithelial cells, are the initial targets of SIV introduced by atraumatic mucosal routes (38), we wondered whether direct submucosal injection might retard the early steps of in vivo infections and thereby attenuate the deleterious effects of the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R administered intravenously. Two rhesus monkeys were therefore inoculated with 100 TCID50 of virus by rectal submucosal injection. One animal (T14) suffered rapid CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion (49 cells/μl at 4.6 weeks postinfection) and high virus loads (1.1 × 108 RNA copies/ml at 2 weeks postinfection) and had to be euthanized at week 12 because of anorexia, lethargy, and marked weight loss (Fig. 5A and B). The second macaque inoculated by submucosal injection was the same animal (903) that failed to become infected following repeated vaginal infusions of SHIVDH12R. Monkey 903 did indeed become infected as a result of the parenteral virus injection, experiencing a rapid but not irreversible CD4+ T cell decline, which leveled off at the 200 cells/μl range (Fig. 5A). Its peak RNA load was slightly lower (2.6 × 107 copies/ml) than that measured for macaque T14 and subsequently declined to unmeasurable levels by week 10 postinfection. Results of immunoblot analyses of these two monkeys were consistent with their respective clinical courses (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

The dynamics of CD4+ T lymphocyte (A), viral RNA (B), and antibody (C) levels in rhesus macaques following submucosal injection of SHIVDH12R. The time (weeks) of death is indicated.

The SHIVDH12R quasispecies evolves in an animal-specific manner in surviving, chronically infected rhesus monkeys.

We had previously molecularly characterized the SHIVDH12R stock by amplifying a 3-kb DNA segment encompassing the vpu, env, and nef genes and determining the nucleotide sequence for 22 independent PCR clones (8). Sequence analysis revealed that amino acid substitutions affecting 13 residues in gp120 and 6 residues in gp41 had accumulated during the evolution of the nonpathogenic SHIVDH12 to the highly pathogenic SHIVDH12R. In addition, other consistent amino acid changes were present in several but not all of the sequenced PCR clones. Thus, the SHIVDH12R tissue culture-derived stock resembled a typical virus quasispecies isolated from HIV-1-infected individuals. Because endpoint, 100% neutralization assays of HIV-1DH12, SHIVDH12, and SHIVDH12R are easy to perform (7, 8, 40), the survival of animals following SHIVDH12R infection provided the opportunity to assess whether the input virus quasispecies had evolved into a neutralization-resistant virus “swarm.”

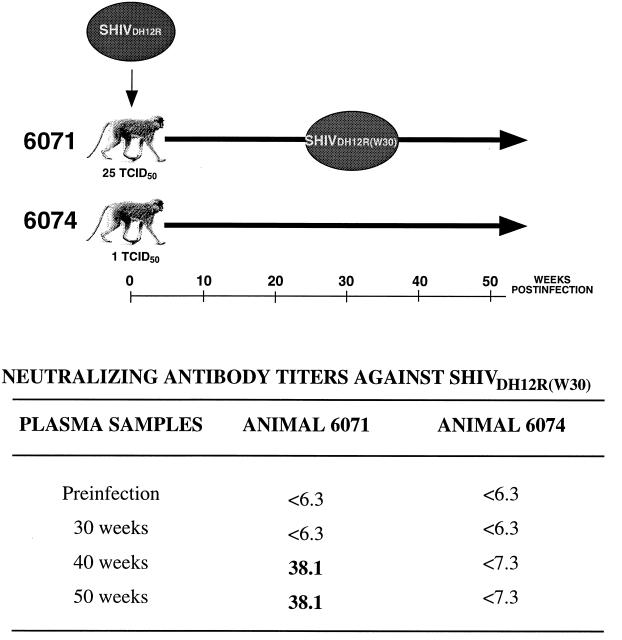

As indicated in Table 2, rhesus monkeys 6071 and 6074, which survived infections initiated with 25 and 1 TCID50 of SHIVDH12R, respectively, both generated neutralizing antibodies against the input virus. At week 30 postinfection, virus was isolated from animal 6071 by cocultivation with naïve rhesus PBMC and was designated SHIVDH12R(W30). Plasma samples collected at week 30 from macaques 6071 and 6074 failed to neutralize SHIVDH12R(W30) (Fig. 6). However, 100% neutralizing activity against SHIVDH12R(W30) became measurable at weeks 40 and 50 in animal 6071 but not in animal 6074. Because the plasma from monkey 6074 continued to produce neutralizing antibody directed against the common SHIVDH12R input even at weeks 40 and 50 postinfection (Table 2), its inability to neutralize SHIVDH12R(W30) is consistent with the antigenic evolution of the SHIVDH12R quasispecies in an animal-specific fashion.

FIG. 6.

Evolution of the SHIVDH12R quasispecies in two rhesus monkeys as monitored by emergence of neutralizing antibody resistance. Macaques 6071 and 6074 were inoculated with SHIVDH12R and both developed SHIVDH12R-specific neutralizing antibodies by week 20 postinfection (see Table 2). Virus was isolated from animal 6071 at 30 weeks postinfection and was designated SHIVDH12R(W30). Plasma samples collected from both animals at the indicated times were assayed for neutralizing activity against SHIVDH12R(W30).

DISCUSSION

In contrast to HIV-1 infections of humans or SIV infections of Asian macaques, in which virus-induced disease occurs in time frames of approximately 10 years and 1 year, respectively (11, 21, 31), highly pathogenic SHIVs are known to cause depletions of CD4+ T lymphocytes within a few weeks of infection and death shortly thereafter (8, 10, 28). The latter clinical course was observed for SHIVDH12R with the interesting addition that its pathogenic effects, following intravenous virus administration, were dose dependent. The attenuating effects of reduced inoculum size were also observed when virus was inoculated by the mucosal route. The failure to establish a SHIVDH12R infection in one of three animals exposed multiple times to 105 TCID50 of virus by intravaginal infusion and the extremely low virus loads measured in a second of these three monkeys very likely reflect the intrinsic protection afforded by mucosa, tissue, and lymph node barriers, all of which are bypassed by intravenous SHIV inoculations.

When SHIVDH12R was administered intravenously, marked and rapid CD4+ T cell loss occurred in all animals and at all virus inoculum sizes. However, with high-input SHIVDH12R inocula (650 TCID50 and greater), CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion was irreversible, was associated with the absence of virus-specific humoral responses, and resulted in intractable symptoms of weakness, diarrhea, and weight loss, requiring euthanasia between weeks 12 and 23 postinfection. In contrast, CD4+ T lymphocyte levels never fell below 50 cells/μl in four of the five rhesus monkeys inoculated intravenously with small (25 TCID50 or less) SHIVDH12R inocula, and these animals exhibited no signs of clinical disease. Interestingly, the CD4+ T cell counts in these asymptomatic macaques remained quite low compared to the preinoculation levels (Fig. 1), stabilizing at the 100- to 500-cells/μl range during a one-year period of observation. Because the accelerated and invariably fatal clinical course in monkeys exposed to large amounts of virus is determined within the first few weeks of infection and appears to be due to the seemingly synchronous loss of CD4+ T cells, this SHIV system may prove useful for assessing the roles of cellular and viral determinants in disease development.

Although we observed a correlation between inoculum size and clinical outcome for rhesus macaques exposed to SHIVDH12R intravenously, this effect has not been reported for monkeys inoculated with pathogenic strains of SIV (3). On the other hand, there have been several reports of seronegative health care workers, newborn infants of HIV-1 positive mothers, needle-sharing drug users, and individuals who have had unprotected sexual intercourse who remain antibody negative yet mount virus-specific T cell responses (32). In some instances, integrated proviral DNA and HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes have been detected in such seronegative persons (12, 25). Although it is not currently understood why these individuals remain antibody negative, it is possible that they were exposed to relatively small amounts of virus and their cell-mediated immune responses controlled the initial rounds of HIV-1 replication, thereby preventing the establishment of a persistent infection.

As previously reported for SIV (19, 37), the establishment of a SHIVDH12R infection by a mucosal route of inoculation (viz. atraumatic intravaginal infusion) was relatively inefficient. Only two of the three animals exposed multiple times to large (5 × 104 TCID50) SHIVDH12R inocula became infected, and each had a benign clinical course. One of these macaques had no significant CD4+ T lymphocyte loss, and the other experienced only partial depletion of this T-cell subset. Plasma viremia in both animals became undetectable by 8 weeks postinfection, and one monkey (H385) produced anti-p27 Gag but no gp120 binding antibody. This latter result suggests that more vigorous and sustained in vivo replication is required to elicit anti-gp120 antibodies.

We have estimated the in vivo infection rate constants associated with the very initial stages of SHIVDH12R infections in rhesus macaques based on an analysis of the plasma virus concentration dynamics. The average infection rate constant (1.06 day−1) for the nine animals in our study inoculated by the intravenous route is lower than the rate constants recently reported for rhesus macaques inoculated with the highly pathogenic SIVmac251, which ranged from 1.4 to 3.2 day−1 (39), for monkeys infected with SIVsmE660 and SIVsmE543-3, which ranged from 0.9 to 2.7 day−1 (22), and for humans infected with HIV-1, which ranged from 1.4 to 3.5 day−1 (16). It had been previously reported that plasma SIV RNA levels measured on day 7 postinfection correlated with levels measured during the postacute phase of infection, suggesting that host factors could exert their effect prior to full development of specific immune responses and be of critical importance for the subsequent clinical course (15). However, a similar study assessing early events during SIV infections of rhesus monkeys found no correlation between the initial virus infection rate constants and clinical outcomes (39). Our results suggest that the very initial kinetics of primate lentivirus infections in vivo may be predictive of the subsequent virus replication patterns and clinical outcomes. However, experiments with more monkeys are needed before any definite conclusions can be reached in this regard. We also estimated the initial rates of SHIVDH12R decline following the peak of infection and found that they are significant predictors of clinical outcome, in agreement with the conclusions reached in a study of pathogenic SIV infections (39).

The homeostatic mechanisms underlying the markedly depressed but stable CD4+ T cell levels associated with the low to undetectable virus loads, as measured by plasma RT-PCR, in rhesus monkeys recovering from SHIVDH12R infections is not presently understood. It is quite possible that these chronically infected animals may survive indefinitely. The presence of readily measurable neutralizing antibodies in many surviving monkeys suggests that their immune systems are capable of successfully controlling a continuous virus infection. On the other hand, because the SHIVDH12R stock is a heterogeneous quasispecies (8), not molecularly cloned virus, it could be formally argued that the survival rate of macaques receiving the smallest virus inocula intravenously simply reflects exposure to relatively small amounts of a highly pathogenic subpopulation present in the administered virus swarm. Resolution of and recovery from the primary SHIVDH12R infection in these animals would therefore depend on eliminating this component of the inoculum. If nonpathogenic variants in the SHIVDH12R inoculum have, in fact, been selected in vivo, one might expect the CD4+ T cell counts to have increased in the surviving monkeys, an outcome that was not observed. An alternative explanation for persistently low levels of CD4+ T lymphocytes is that even though a highly cytopathic virus component in the challenge stock was eliminated in vivo, CD4+ T-cell subsets, possibly lost irreversibly during the primary infection, can never be or are very slowly being replenished (26, 30). These questions could be partially resolved by isolating virus from animals chronically infected with SHIVDH12R and inoculating naïve monkeys with the recovered virus. If, in fact, the recovered SHIV fails to induce disease following intravenous inoculation, one might conclude that the asymptomatic clinical course for the surviving macaques is due to selection in vivo of a relatively nonpathogenic virus. Whether or not this system models the disease-free period experienced by HIV-1-infected individuals following the resolution of their primary virus infections remains to be determined.

As noted earlier, gp120 epitopes associated with the DH12 family of primate lentiviruses appear to be the sole targets of neutralizing antibodies elicited in chronically infected nonhuman primate species (M. W. Cho, unpublished data). This conclusion is also consistent with results presented in this report showing that the two animals (H358 and H385) generating anti-p27 but no detectable anti-gp120 antibodies (Fig. 3 and 4C) failed to neutralize SHIVDH12R (Table 2 and Results). The capacity of surviving SHIVDH12R-infected macaques to produce neutralizing antibodies has been exploited to monitor the evolution of a primate lentivirus quasispecies during long-term passage in vivo. As is the case for HIV-1-infected persons (24), a chronically SHIVDH12R-infected rhesus monkey (6071) was unable to neutralize an autologous contemporary virus isolate (SHIVDH12R(W30)), although neutralizing antibody against the originally inoculated SHIVDH12R continued to be produced (Table 2 and Fig. 6). This same animal subsequently generated neutralizing antibody against SHIVDH12R(W30). Not unexpectedly, the initial virus quasispecies evolved differently in a second SHIVDH12R-inoculated macaque, which never made neutralizing antibodies against SHIVDH12R(W30). This result raises interesting possibilities relevant to vaccine development that could be examined with the SHIVDH12R system described. For example, it could be argued that virus quasispecies escape merely reflects the de novo emergence of novel gp120 genotypes, a consequence of in vivo selection and the error-prone reverse transcription reaction. Alternatively, it is possible that the SHIVDH12R quasispecies undergoes antigenic selection but not genotypic change by expansions and contractions of its constituent viral subpopulations, thereby altering the capacity of an earlier humoral response to control a contemporary virus swarm. Irrespective of these explanations, the persistence of neutralizing antibody directed against the initial SHIVDH12R quasispecies is most consistent with the continued presence and active replication of the original SHIV swarm. Some of these possibilities can be examined by biological and molecular characterizations of virus subsequently recovered from animals initially exposed to the same SHIVDH12R quasispecies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Carol Clarke, Charles Thornton, and Russ Byrum for their diligence and assistance in the care and maintenance of our animals. We are also grateful to Vanessa Hirsch for providing SIV-infected macaque plasma, Michael Cho for supplying gp120 expressed from recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells, and Michael Eckhaus, Georgina Miller, and David Green for pathological analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cho M W, Shibata R, Martin M A. Infection of chimpanzee peripheral blood mononuclear cells by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 requires cooperative interaction between multiple variable regions of gp120. J Virol. 1996;70:7318–7321. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7318-7321.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services publication no. (NIH) 85-23, revised ed. Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniel M D, Letvin N L, Sehgal P K, Hunsmann G, Schmidt D K, King N W, Desrosiers R C. Long-term persistent infection of macaque monkeys with the simian immunodeficiency virus. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:3183–3189. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-12-3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewar R L, Highbarger H C, Sarmiento M D, Todd J A, Vasudevachari M B, Davey R T, Jr, Kovacs J A, Salzman N P, Lane H C, Urdea M S. Application of branched DNA signal amplification to monitor human immunodeficiency virus type 1 burden in human plasma. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1172–1179. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitrov D S, Willey R L, Sato H, Chang L-J, Blumenthal R, Martin M A. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J Virol. 1993;67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2182-2190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fultz P N, Schwiebert R, Stallworth J. AIDS-like disease following mucosal infection of pig-tailed macaques with SIVsmmPBj14. J Med Primatol. 1995;24:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1995.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Igarashi T, Brown C, Azadegan A, Haigwood N, Dimitrov D, Martin M A, Shibata R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing antibodies accelerate clearance of cell-free virions from blood plasma. Nat Med. 1999;5:211–216. doi: 10.1038/5576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igarashi T, Endo Y, Englund G, Sadjadpour R, Matano T, Buckler C, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Theodore T, Shibata R, Martin M. Emergence of a highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus in a rhesus macaque treated with anti-CD8 mAb during a primary infection with a nonpathogenic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14049–14054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin M J, Rogers J, Phillip-Conroy J E, Allan J S, Desrosiers R C, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. Infection of a yellow baboon with simian immunodeficiency virus from African green monkeys: evidence for cross-species transmission in the wild. J Virol. 1994;68:8454–8460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8454-8460.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresma L, Stephens E B, Zhao L-J, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kestler H, Kodama T, Ringler D, Marthas M, Pedersen N, Lackner A, Regier D, Sehgal P, Daniel M, King N, Desrosiers R. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science. 1990;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langlade-Demoyen P, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Ferchal F, Oksenhendler E. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) nef-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in noninfected heterosexual contact of HIV-infected patients. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:1293–1297. doi: 10.1172/JCI117085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law L W. Transmission studies of a leukemogenic virus, MLV, in mice. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1966;22:267–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lifson J D, Nowak M A, Goldstein S, Rossio J L, Kinter A, Vasquez G, Wiltrout T A, Brown C, Schneider D, Wahl L, Lloyd A L, Williams J, Elkins W R, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:9508–9514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9508-9514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little S J, McLean A R, Spina C A, Richman D D, Havlir D V. Viral dynamics of acute HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 1999;190:841–850. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Y, Pauza C D, Lu X, Montefiori D C, Miller C J. Rhesus macaques that become systemically infected with pathogenic SHIV 89.6-PD after intravenous, rectal, or vaginal inoculation and fail to make an antiviral antibody response rapidly develop AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:6–18. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199809010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marthas M L, Miller C J, Sutjipto S, Higgins J, Torten J, Lohman B L, Unger R E, Ramos R A, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Efficacy of live-attenuated and whole-inactivated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines against vaginal challenge with virulent SIV. J Med Primatol. 1992;21:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller C J, Alexander N J, Sutjipto S, Joye S M, Hendrickx A G, Jennings M, Marx P A. Effect of virus dose and nonoxynol-9 on the genital transmission of SIV in rhesus macaques. J Med Primatol. 1990;19:401–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller C J, Marthas M, Greenier J, Lu D, Dailey P J, Lu Y. In vivo replication capacity rather than in vitro macrophage tropism predicts efficiency of vaginal transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus or simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:3248–3258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3248-3258.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss A R, Bacchetti P. Natural history of HIV infection. AIDS. 1989;3:55–61. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak M A, Lloyd A L, Vasquez G M, Wiltrout T A, Wahl L M, Bischofberger N, Williams J, Kinter A, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M, Lifson J D. Viral dynamics of primary viremia and antiretroviral therapy in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:7518–7525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7518-7525.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pauza C D, Emau P, Salvato M S, Trivedi P, MacKenzie D, Malkovsky M, Uno H, Schultz K T. Pathogenesis of SIVmac251 after atraumatic inoculation of the rectal mucosa in rhesus monkeys. J Med Primatol. 1993;22:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilgrim A K, Pantaleo G, Cohen O J, Fink L M, Zhou J Y, Zhou J T, Bolognesi D P, Fauci A S, Montefiori D C. Neutralizing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in primary infection and long-term-nonprogressive infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:924–932. doi: 10.1086/516508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto L A, Sullivan J, Berzofsky J A, Clerici M, Kessler H A, Landay A L, Shearer G M. ENV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in HIV seronegative health care workers occupationally exposed to HIV-contaminated body fluids. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:867–876. doi: 10.1172/JCI118133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitcher C J, Quittner C, Peterson D M, Connors M, Koup R A, Maino V C, Picker L J. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in most individuals with active HIV-1 infection, but decline with prolonged viral suppression. Nat Med. 1999;5:518–525. doi: 10.1038/8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent end points. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I-W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reimann K A, Li J T, Voss G, Lekutis C, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Lin W, Montefiori D C, Lee-Parritz D E, Lu Y, Collman R G, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. An env gene derived from a primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate confers high in vivo replicative capacity to a chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3198-3206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg E S, Billingsley J M, Caliendo A M, Boswell S L, Sax P E, Kalams S A, Walker B D. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seage G R, III, Oddleifson S, Carr E, Shea B, Makarewicz-Robert L, van Beuzekom M, De Maria A. Survival with AIDS in Massachusetts, 1979 to 1989. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:72–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shearer G M, Clerici M. Protective immunity against HIV infection: has nature done the experiment for us? Immunol Today. 1996;17:21–24. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata R, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, Buckler-White A, Ogert R, Ross W, Willey R, Cho M W, Martin M A. Neutralizing antibody directed against the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein can completely block HIV-1/ SIV chimeric virus infections of macaque monkeys. Nat Med. 1999;5:204–210. doi: 10.1038/5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibata R, Kawamura M, Sakai H, Hayami M, Ishimoto A, Adachi A. Generation of a chimeric human and simian immunodeficiency virus infectious to monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 1991;65:3514–3520. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3514-3520.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata R, Maldarelli F, Siemon C, Matano T, Parta M, Miller G, Fredrickson T, Martin M A. Infection and pathogenicity of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques: determinants of high virus loads and CD4 cell killing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:362–373. doi: 10.1086/514053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibata R, Siemon C, Czajak S C, Desrosiers R C, Martin M A. Live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines elicit potent resistance against a challenge with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric virus. J Virol. 1997;71:8141–8148. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8141-8148.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sodora D L, Gettie A, Miller C J, Marx P A. Vaginal transmission of SIV: assessing infectivity and hormonal influences in macaques inoculated with cell-free and cell-associated viral stocks. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14(Suppl. 1):S119–S123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spira A I, Marx P A, Patterson B K, Mahoney J, Koup R A, Wolinsky S M, Ho D D. Cellular targets of infection and route of viral dissemination after an intravaginal inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus into rhesus macaques. J Exp Med. 1996;183:215–225. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staprans S I, Dailey P J, Rosenthal A, Horton C, Grant R M, Lerche N, Feinberg M B. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J Virol. 1999;73:4829–4839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4829-4839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willey R L, Shibata R, Freed E O, Cho M W, Martin M A. Differential glycosylation, virion incorporation, and sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope produced from infected primary T-lymphocyte and macrophage cultures. J Virol. 1996;70:6431–6436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6431-6436.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto J K, Hansen H, Ho E W, Morishita T Y, Okuda T, Sawa T R, Nakamura R M, Pedersen N C. Epidemiologic and clinical aspects of feline immunodeficiency virus infection in cats from the continental United States and Canada and possible mode of transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;194:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]