An editorial last year in the Washington Post challenged directors of drug companies to reduce the cost of HIV drugs in poor countries to zero. Here the reproduced editorial is accompanied by a discussion about why it was written and the response to it. We invited comment from one of the named directors and from a man with AIDS who refuses to take antiretroviral drugs until they are available to the public sector in South Africa

Last year I wrote a guest editorial for the Washington Post in which I challenged the world's pharmaceutical companies to cut the cost of HIV drugs to zero in poor countries (see box on next page).1 Here I explain why I wrote it and describe some of the responses it provoked.

Summary points

Complex drug regimens, combined with social support, have been used to treat infectious diseases, even in conditions of extreme poverty

The high costs of drugs can be used as an excuse for poor countries not to construct effective infrastructures for the care of patients with chronic infectious diseases

Dramatic reductions in the costs of antituberculosis drugs catalysed worldwide action against multiresistant tuberculosis

The boards and executives of drug companies could catalyse action against the AIDS epidemic by immediately reducing the costs of HIV drugs in poor countries to zero

The prologue

People living in poverty being denied access to modern health care is a form of violent, systematic social deprivation that we, as a civilised global community, ought not to accept. Even the poorest people in the poorest settings can, if they are allowed and assisted, be involved in improving their health and can benefit from the most advanced drugs.

This philosophy of social justice drives the international health programme Partners in Health, which was founded by Paul Farmer and Jim Yong Kim. Partners in Health is tackling a seemingly impossible problem: the treatment of multiresistant tuberculosis in a poor shanty town area called Carabayllo on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, and in rural Haiti.2 The organisation has trained local residents as healthcare “promoters” able to give complex regimens of drugs to patients during directly observed treatment, while providing the patients and their families with a lot of psychosocial support. Success rates have been phenomenal—over 80% of patients have apparently been cured of a disease that only five years ago was thought of in these areas as a death sentence.

Kim's and Farmer's work is changing minds. Until recently, the World Health Organization advised most developing nations not to spend their resources on the diagnostic tools and complex drug regimens used to treat multiresistant tuberculosis in rich nations.3 But now, thanks in part to advocacy from Partners in Health and other organisations, the WHO has at last placed many of the drugs needed to treat multiresistant tuberculosis on its list of essential drugs. Many pharmaceutical manufacturers have reduced the prices of antituberculosis drugs by more than one order of magnitude.4

In the international struggle against multiresistant tuberculosis, the sudden and dramatic decrease in the costs of antituberculosis medications was an important catalyst to action. When high costs meant that drugs were far out of reach, it seemed futile for poor countries to try to build infrastructures capable of managing patients with tuberculosis. When drugs became affordable, building a proper healthcare system was a task worth tackling. Peru has begun to broaden the Carabayllo programme to a national scale, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation supports plans to broaden the impact of Partners in Health with multimillion dollar investment.

It takes little imagination to carry one's mind from one scourge—multiresistant tuberculosis—to another—AIDS.5 The challenges are similar, and despair is just as seductive. AIDS is not yet curable, but modern medicine has chipped away at the pace and burden of the disease's progression. Sophisticated drug regimens can increase the healthy portion of the lives of people with HIV by years, even decades. Worldwide, the stakes are as high as our species has ever known. Without widely available care and effective prevention, AIDS is creating a pandemic without precedent on our planet.6 With proper care and active prevention, we could save millions and millions of years of healthy life.7,8

The work of Partners in Health led me, one sleepless night, to write an article about AIDS for an American national newspaper. I wrote a challenge as a guest editorial in the Washington Post.1 Reduce the costs of anti-HIV drugs to zero, or nearly so, I proposed. I directed this challenge at the few people who, with a stroke of their pens, could make it happen the next morning—the executives and boards of the world's pharmaceutical companies.

The Washington Post editorial

We all have AIDS

In many occupied nations during World War II, the Nazis ordered Jews to wear a yellow star, as prelude to their destruction. But not in Denmark. According to legend, the Danish king, Christian X, threatened that, if Danish Jews were to wear the star, he would, too. The story is almost certainly a myth, but its meaning is not. Despite the Nazi occupation, Denmark rescued the overwhelming majority of its Jews. “If some Danes are under siege,” the story means to say, “then all Danes are under siege. So, for now, we are all Jews.”

Now we all have AIDS. No other construction is any longer reasonable. The earth has AIDS; 36.1 million people at the end of the year 2000. In Botswana, 36 percent of adults are infected with HIV; in South Africa 20 percent. Three million humans died of AIDS in the year 2000, 2.4 million of them in sub-Saharan Africa. That is a Holocaust every two years; the entire population of Oregon, Iowa, Connecticut or Ireland dead last year, and next year, and next. More deaths since the AIDS epidemic began than in the Black Death of the Middle Ages. It is the most lethal epidemic in recorded history.

Prevention will be the most important way to attack AIDS everywhere, but treatment matters, too. We can treat AIDS effectively. We cannot cure its victims, but we can extend their healthy lives by years—with luck, by decades. We can reduce its transmission from infected mother to unborn child by two-thirds or more. We are seeing the effects of advancing science plus enlightened public health policies in the United States, where the toll of AIDS began to fall in 1997.

Successful, life-prolonging management of HIV infection is not simple. Important dimensions include education, social support and life-style interventions that are extremely difficult to achieve in the developed nations, and many times more so in impoverished nations. But it is a mistake to ignore the role of medications. In New York, San Francisco or Nairobi, no matter how different the cultural challenges, the correct mainstay of lifesaving care for the unborn child or the infected adult is medicine, given in a timely, scientifically accurate and reliable way.

Most people on earth with HIV and AIDS do not get those medicines. The barriers are partly social and logistical, but the overwhelming barrier is cost. At current prices, one year of triple drug therapy for an HIV-positive person costs $15,000. Recent, welcome changes by a few progressive pharmaceutical companies, like Merck & Co., promise to reduce that cost by thousands of dollars per year.

But keep in mind that no legend claims King Christian talked of putting on only half a yellow star.

Here is what the world needs: free anti-AIDS medicines. The devastated nations of the world need AIDS medicines at no cost at all, or, at a bare minimum, medicines available at exactly their marginal costs of manufacture, not loaded at all with indirect costs or amortized costs of development. No hand-waving or accounting maneuvers—for all practical purposes, free.

Here is how it could happen: the board chairs and executives of the world's leading drug companies decide to do it, period. To the anxious corporate lawyers, the incredulous stockholders, the cynical regulators and the suspicious public, they say, together, the same thing:

“The earth has AIDS, and therefore we all, for now, have AIDS. Therefore, we are taking one simple action that will save millions and millions of lives. We choose to do it, together, and we will use the intelligence of our own forces to figure out how to make it possible, while preserving the futures of our companies.”

No one could stop them; none would dare try. For the small profit they would lose, they would gain the trust and gratitude of the entire world. They would have created a story to be told for a millennium, and those who depend on the prudence of these leaders—on their “fiduciary responsibility”—might chose then not to blame them but to join them in celebration, as fiduciaries of humankind.

The names of the people who can say this, together, include these: Raymond Gilmartin, (chairman and CEO of Merck & Co.); Sir Richard Sykes and Jean-Pierre Garnier (respectively chairman and CEO of GlaxoSmithKline); Charles A Heimbold, Jr, and Peter Dolan (respectively chairman/CEO and president of Bristol-Myers Squibb); Dr Franz B Humer (chairman and CEO of Roche). There are others; they know who they are. These few souls, with this act, would ultimately save the lives of more human beings than died in the Holocaust—perhaps two or three times over.

If a Nobel Prize followed, it would be redundant. The memory of the deed would likely outlive even the story of the Danish king who joined his people in their need.

[C A Heimbold Jr has since retired from Bristol-Myers Squibb.]

The online debate

The Washington Post hosts question and answer sessions on line on the day that guest editorials are published. I spent two hours answering selected questions from readers. It was an opportunity an author rarely gets—to hear first hand how the reader feels at the moment of reading.

The questions I received provided a cross section of public opinions—some encouraging, some shocking —on our possible role as developed nations in solving the world's AIDS crisis.

Several of the questions debated serious points of fact and evidence.

Would “attitude, cultural traditions, and gender discrimination” in poor countries “have an adverse effect on the battles against AIDS,” even if medications were free? (I replied that removing the barriers of drug costs would, in fact, confront us with the need to tackle such obstacles. High drug costs are an excuse for avoiding other issues.)

Do “infrastructures” exist to distribute medications and manage treatment? (I cited the success of Partners in Health in developing and sustaining effective infrastructures.)

Some questions raised concerns about the implications for the pharmaceutical industry if it took my suggestion of making AIDS drugs free.

“Where does the r[esearch] and d[evelopment] money come from? Current profits. If you take away the profits, then the companies will have no incentive to do . . . research.” (I replied that drug companies today get no profits, anyway, from countries that cannot afford their products, and that the international goodwill that could come from bold generosity could put the companies in a much better position to make the case for support for their research agendas.)

Some readers questioned whether AIDS care deserves such priority.

“If drug companies ought to provide free AIDS drugs, by the same moral principle they ought to provide free antibiotics and . . . every lifesaving drug.” (This “Pandora's box” argument is a formula for paralysis. “Let's start somewhere, instead of nowhere,” I replied. “And why not with at least one of the greatest scourges we face in the world today?”)

Questions about where responsibility for dealing with AIDS ought to lie were disturbing to me, because of what they suggested about the potential will for global action.

“AIDS in most parts of the world is associated with behaviour . . . something over which people have some control.” (So, should we therefore also not treat other “behaviour induced diseases,” such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and sports injuries?)

“So who will ultimately end up paying for these drugs? . . . [I]t will be just another thing for the taxpayers to eat? . . . How is this [free drugs] supposed to help people help themselves?” (“This is why we have communities,” I replied, “including a global community.”)

One email correspondent asked why he should care about AIDS in Africa. “What does this have to do with me?” he asked. “I deeply believe we are one world,” I responded, “and all humankind are connected.” He replied instantly with a further question, which haunts me still. “Where did you get that idea?” he asked.

Conclusion

Seven months after the editorial appeared, one drug company executive has replied to me. He described and celebrated in a letter important steps his firm has taken to reduce the financial barriers to AIDS care and to support treatment and prevention programmes, steps that I knew about before I wrote the editorial, and that I applaud.

GISELE WULFSOHN/PANOS

But that is not enough, and it is not what I am asking for. These initial acts of generosity only set the stage for what the world really needs: a dramatic, unprecedented, and unequivocal decision by the boards and executives of several important pharmaceutical companies to make their anti-HIV drugs free. Not half a loaf—a whole loaf. If they did that, these leaders would change the face of the world.

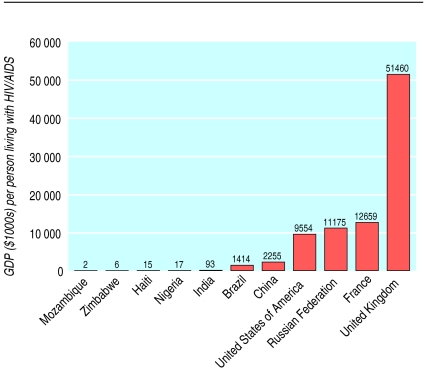

Figure.

Amount of gross domestic product in relation to number of people living with HIV infection or AIDS, 1997 (data from www.cptech.org/ip/health/)

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Berwick DM. We all have AIDS. Washington: Washington Post, Jun 26 2001:A17.

- 2.Farmer P, Kim JY. Community based approaches to the control of multidrug resistant tuberculosis: introducing “DOTS-plus.”. BMJ. 1998;317:671–674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta R, Kim JY, Espinal MA, Caudron J-M, Pecoul B, Farmer PE, et al. Responding to market failures in tuberculosis control. Science. 2001;293:1049–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.1061861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmer P, Léandre F, Mukherjee JS, Claude MS, Nevil P, Smith-Fawzi MC, et al. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2001;358:404–409. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) AIDS epidemic update: December 2000. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfield TL, Chiesi A, Miller V, Gargalianos P, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Lancet. 1998;352:1725–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palella FJ, Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]