Abstract

Background

The Functional Movement Screen™ (FMS™) is widely used to assess functional movement patterns and illuminate movement dysfunctions that may have a role in injury risk. However, the association between FMS™ scores and LBP remains uncertain.

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine functional movement scores among patients with low back pain (LBP) and healthy subjects with no LBP and review the validity of the FMS™ tool for screening functional movement among LBP patients.

Methods

The systematic review and meta-analysis included papers assessing functional movement among adult patients with LBP using the FMS™ through a literature review of five databases. The search strategy focused used relevant keywords: Functional movement screen AND low back pain. The review included all papers assessing functional movement among LBP adult patients (>18 years old) using the FMS™ published between 2003 to 2023. The risk of bias in the involved studies was evaluated using the updated Cochrane ROB 2 tool. Statistical analysis was conducted using Review Manager software, version 5.4. The meta-analysis included the total FMS™ score and the scores of the seven FMS™ movement patterns.

Results

Seven studies were included in this systematic review were considered to have low to unclear risk of bias. The meta-analysis revealed that the LBP group had a significantly lower total FMS™ score than the control group by 1.81 points (95% CI (-3.02, -0.59), p= 0.004). Patients with LBP had a significantly lower score than the control group regarding FMS™ movement patterns, the deep squat (p <0.01), the hurdle step (p <0.01), the inline lunge (P value <0.01), the active straight leg raise (p <0.01), the trunk stability push-up (p=0.02), and the rotational stability screens (p <0.01).

Conclusion

Lower scores on the FMS™ are associated with impaired functional movement. Identifying the specific functional movement impairments linked to LBP can assist in the creation of personalized treatment plans and interventions. Further research is needed to assess the association of cofounders, such as age, gender, and body mass index, with the FMS™ score among LBP patients and controls.

Level of evidence

1

Keywords: low back pain, functional movement screen, pain, injury risk, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is a widespread musculoskeletal condition that affects up to 80% of individuals throughout their lifetime.1 It is considered the most common disorder in gymnastics, football, volleyball, and tennis athletes, accounting for 20% of sports injuries involving the spine.2,3 LBP is typically categorized as mechanical, rheumatic, infectious, tumoral, or mental, with mechanical LBP being the most common, around 90% of cases.4 Various factors may contribute to LBP incidence, including age, smoking, genetics, weight (gain), improper weightlifting, nutritional disorders, decreased flexibility and hydration, acute injuries, chronic stress, and poor physical conditions.5,6

The evaluation of patients with LBP, including conducting functional evaluations, is crucial in the clinical field.7 Several tools are used to assess patients with LBP, such as the Back Pain Functional Score, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ), Patient-specific Functional Scale (PSFS), and the Functional Movement Screen™ (FMS™).8

The FMS™ assesses movement patterns and identifies restrictions and compensations. The primary objective of the FMS™ is to evaluate an individual’s ability to perform various movements, including those related to flexibility, range of motion, muscle strength, coordination, balance, and proprioception. It consists of seven component movements; the deep squat, hurdle step, inline lunge, shoulder mobility, active straight leg raise, push-up, and rotational stability movements. Several of these movements are performed bilaterally and when tests are performed bilaterally, the lower of the two scores is used for analysis.The assessment is carried out through standardized verbal instructions and visual inspection. FMS™ scores are assigned based on task performance, including movement conditions with or without pain and symmetry.9,10 The score for each movement ranges from 0 to 3, with a total cumulative score ranging from 0 to 21 points.11,12 Lower scores (≤14) on the FMS™ indicate impaired functional movements associated with the potential for a higher risk of injury.13

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to examine functional movement scores among patients with low back pain (LBP) and healthy subjects with no LBP and review the validity of the FMS™ tool for screening functional movement among LBP patients.

METHODOLOGY

This systematic review complied with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria.14

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted through a thorough literature search of PubMed, Medline, Ovid, Scopus, and Central research databases using the keywords Functional movement screen AND low back pain. Studies published from 2003 to 2023 were screened to select studies that matched the inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Furthermore, selected study references were reviewed manually to identify similar studies. Only studies that compared the FMS™ between patients with chronic LBP and healthy control subjects were incorporated in the meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Papers assessing functional movement among adult patients with LBP (>18 years old) with FMS™ and published from 2003 to 2023 were included. Studies published in languages other than English were excluded. Narrative reviews, systematic reviews, consensus reports, case reports, case series, duplicated studies, published before 2003, studies with insufficient data or findings regarding FMSTM score, studies with irrelevant findings, studies that used other functional movement tools or assessed patients with another type of pain, and studies for which full text was unavailable were also excluded. Only studies that compared the FMS™ between patients with chronic LBP and healthy control subjects were incorporated in the meta-analysis.

Screening and data extraction

First, title and abstract screening was performed by the authors. Relevant full-text papers and evaluated the research for inclusion criteria were examined by one author. After articles were selected for inclusion, data were extracted and entered in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Extracted data included authors, year of publication, objective, study design, sample size, gender, age, intervention, assessment tool, results, and outcome. Further data for the meta-analyses included total FMS™ score, in addition to scores of the seven FMS™ composite tests were extracted from the articles included in this systematic review.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

The risk of bias in the incorporated papers was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 (ROB 2) tool. The ROB 2 tool offers a structured, standardized, and flexible approach to assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials and non-randomized studies of interventions.15 The tool assesses quality based on five major domains: bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in the measurement of the outcome, and bias in the selection of the reported result. Each domain has a set of signaling questions that inform the risk of bias judgment for that domain. Based on the responses to each domain, the options for a domain-level risk-of-bias judgment are ‘Low’, ‘High’, or ‘Unclear’ risk of bias. A total or overall risk of bias score for each article was not determined.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager, version 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England) was used for data entry and analysis. The standard deviation (SD) of the means were estimated from CI limits or standard mean difference (if not provided). The size of the continuous outcomes effect was reported as standard mean difference (SMD), and the precision of effect size was also reported as a 95% confidence interval (CI). DerSimonian and Laird’s random-effects model was used to compute SMD.16 Cochrane Q tests and Leave one out (I²) statistics were used to evaluate the heterogeneity and inconsistency across the studies. Leave one out meta-analysis was used for sensitivity analysis to recognize that the overall effect (against which heterogeneity is measured) changes each time an influential study is excluded.17 Statistical significance was set at p < 0.01 for Cochrane Q tests. If a high heterogeneity was detected, a leave-one-out test (removing studies one by one) was performed.

RESULTS

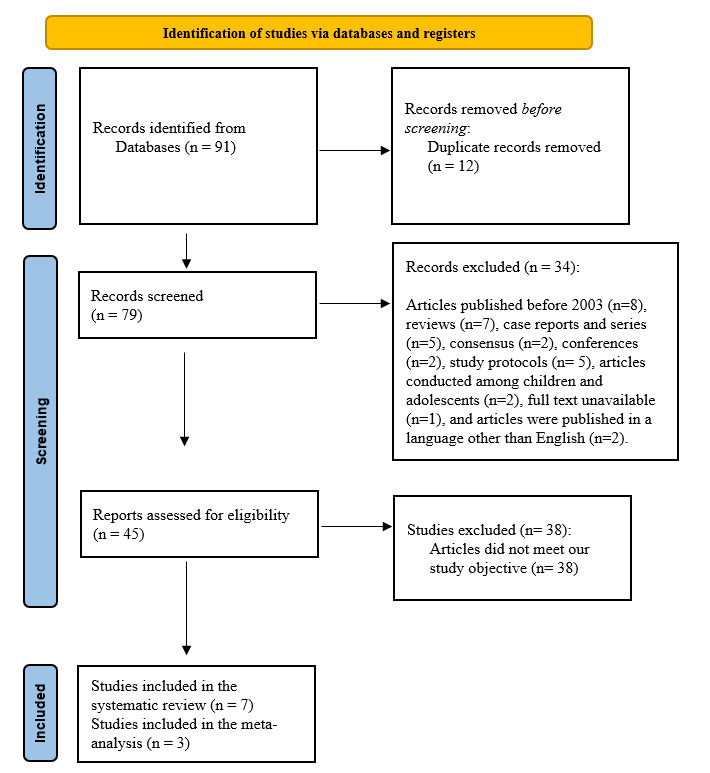

The initial search strategy provided 91 papers, of which 12 were omitted as duplicates. Regarding the remaining 79 articles, 34 were excluded because they did not match the inclusion criteria. Following screening and assessment, 38 additional articles were excluded because they did not match the study’s objective. Seven studies were considered suitable for and included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Studies involved in this systematic review.

Overview of the included studies

In terms of the seven included papers, all were published between 2016 and 2023 (Table 1). The articles included 272 adult subjects with an age range of 18-65 years old. The study subjects were patients with LBP, and either athletes, or healthy controls without LBP. The study design varied among the articles; one study was a double-blinded randomized clinical trial,18 one was a reliability and validity study,19 one was a cross-sectional study,20 and Four were prospective studies.7,21–23 Some studies included either males or females, and others included both genders. All included studies assessed LBP using the FMSTM, but one study also used the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) and Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire (OSW).18 Only one study used intervention which included spinal stabilization exercises (SSEs) and general exercises (GEs).18

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, year | Objective | Study design | Sample size | Study subjects | Sex | Age | Intervention | Assessment tool | Results | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkhathami K et al., 202318 | Assessing SSEs effects on the level of movement performance, pain intensity, and disability among adults with CLBP. | Double-blinded randomized clinical trial. | 40 | Adults with CLBP | Both males and females | 18 to 65 years (39.9 ± 12.5) |

SSEs vs. GEs | FMS TM, NPRS, and OSW | Over eight weeks, there was a substantial difference in modified FMS TM scores between the SSE and GE groups. -The modified FMS TM scores of all patients improved significantly between two adjacent time points: from baseline to two weeks (p = 0.011), two weeks to four weeks (p = 0.001), and four weeks to eight weeks (p = 0.008). |

The modified FMSTM with a scoring system might effectively assess mobility quality in individuals with LBP. |

| Alkhathami K et al., 202119 | It detects the reliability and validity of the FMS™ with a modified scoring system among young adults with and without LBP. | Reliability and validity study | 44 | LBP and asymptomatic individuals | Both males and females | LBP group: 26.08 ±4.03, and asymptomatic group: 25.33 ±2.99. | Nil | FMS™ | The LBP group scored significantly lower than those without LBP (p-value = 0.008). | -It is considered that the FMS TM can differentiate between people who have and do not have LBP. For doctors, FMS TM might be a helpful test for evaluating movement quality and identifying mobility limits in LBP patients. |

| Khoshroo F et al., 202121 | Comparing females with LBP functional movement patterns with NPDs. | NA | 60 | Subjects with LBP and NPDs. | Females | LBP: 26.86 ± 2.22 and NPDs: 26.53 ±2.37. | Nil | FMS™ | - Significant lower scores in LBPDs compared to NPDs in the FMS TM composite score (12.06 vs. 16.43, p-value < 0.001). -There was a negative association between FMS TM composite score and LBP intensity (r (60) = –0.724, p < 0.001) and positive with LBP onset (r (60) = 0.277, p = 0.032) during prolonged standing. |

-LBPD females, who are at higher risk for developing LBP, had significantly lower functional movement quality patterns compared to NPDs. -The FMS TM could predict subjects at risk for LBP development during prolonged standing. |

| Enoki S et al., 202020 | -Assessing and examining the physical characteristics of pole vaulters with chronic LBP. -Clarifying the association between FMS™ performance with and without chronic LBP. |

A cross-sectional study | 20 | collegiate pole vaulters | Males | 19.6 ± 1.1 | Nil | FMS™ | -In the chronic LBP group, the difference between the passive and active SLR angle (SLR) was substantially greater than in the non-chronic LBP group (p-value 0.05). -Those with persistent LBP were more likely to have an FMS TM 14 score. |

- The CLPB group was far more likely to have an FMSTM composite score ≤ 14. -It is critical to examine the active straight leg rise (vs. passive only) and basic motions of pole vaulters using the FMS TM. |

| Gonzalez SL et al., 201822 | Assessing if the FMS™ and impairments can identify rowers at risk for LBP development. | Prospective cohort study | 31 | Collegiate Athletes | Females | 19.7 ± 1.5 years | Nil | FMS™ | There were no differences in FMS™ or impairments between the Uninjured and LBP groups. The FMS™ cutoff score was 16 points. | An FMS TM score of 16 predicted a small increased risk of LBP development (1.4) compared to individuals with scores over 16. However, the FMS TM is not suggested for screening female rowers since the risk ratio was minimal and the 95% confidence interval was broad. |

| Clay H et al., 20123 | They were determining whether the FMS™ scores predict the incidence of all injuries, such as LBP, among female collegiate rowers during one rowing season. | Prospective cohort study | 37 | Collegiate rowers | Females only | Figh risk: 19.25 ± 1.17 Low risk: 19.55 ± 1.21 |

Nil | FMS™ | -Subjects detected as a high risk of injury by the FMS™ were more likely to have LBP during the season (p-value =0.036). -Individuals with LBP history were six times more likely to suffer from LBP during the season (p-value=0.027). | -The FMS™ has been estimated to predict injury among athletes. -The FMS™ has indicated a higher likelihood of a subjective report of LBP. |

| Ko MJ et al., 20167 | Comparing the FMS TM scores between CLBP patients and healthy control subjects with using the FMS™ as an evaluation tool for examining functional deficits of CLBP in patients. | NA | 40 | CLBP patients and healthy controls | Both genders | CLBP:42.20 ± 14.66 and control:43.20 ± 14.41 years | Nil | FMS™ | - CLBP patients scored significantly lower on total composite scores (10.95 ± 2.2 points) compared with the control group (14.40 ± 1.8 points), p<0.001). -LBP patients had significantly lower scores on deep squat (1.55 ± 0.7 vs. 2.20 ± 0.5 points, p=0.002), hurdle step (1.95 ± 0.4 vs. 2.45 ± 0.5 points, p=0.002), ASLR (1.85 ± 0.7 vs. 2.55 ± 0.8 points, p=0.005), and rotary stability (1.15 ± 0.4 vs. 1.80 ± 0.4 points, p<0.001). -There were no significant differences between CLBP patients and the control group in inline lunge (1.90 ± 0.7 vs. 2.25 ± 0.7 points, p-value= 0.133), shoulder mobility (1.75 ± 0.9 vs. 1.85 ± 0.6 points, p-value= 0.811), and trunk stability push-up (0.95 ± 0.5 vs. 1.30 ± 0.6 points, p-value=0.056). |

The deep squat, hurdle step, active straight leg raise, and rotary stability tasks of FMS™ could be recommended as functional assessment tools to assess functional deficits in CLBP patients. |

CLBP: Chronic low back pain, GEs: General exercises, LBP: Low back pain, NA: Not available, NPDs: Non-pain developers, NPRS: Numeric Pain Rating Scale, OSW: Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, SLR: Straight leg raise, SSEs: spinal stabilization exercises.

Overview of Studies’ Risk of Bias

Table 2 shows a representation of the risk of bias assessment.

Table 2. Risk-of-bias summary.

| Reference | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkhathami K et al., 2023,18 | + | + | + | + | ? | + | + |

| Alkhathami K et al., 202119 | + | + | ? | ? | + | + | ? |

| Khoshroo F et al., 202120 | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + |

| Enoki S et al., 202021 | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + |

| Gonzalez SL et al., 201822 | + | + | - | - | ? | + | + |

| Clay H et al., 201623 | + | + | ? | ? | ? | + | + |

| Ko MJ et al., 20167 | ? | ? | - | - | + | + | ? |

(+) Low risk of bias, (-) High risk of bias, (?) Unclear risk of bias

Regarding sequence generation and allocation concealment, six studies had a low risk of bias and an unclear risk of bias. In blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcome assessment, two studies had a high risk of bias, one study had a low risk of bias, and four studies had an unclear risk of bias. Moreover, five studies showed an unclear risk of bias, and two studies had a high risk of bias regarding the incomplete outcome data section. All studies had a high risk of bias in the selective reporting section. However, regarding other sources of bias, five studies had a high risk of bias, while two had an unclear risk of bias. Overall, the included studies should be considered to have low to unclear risk of bias.

Meta-analysis results

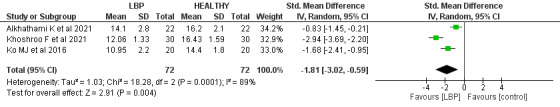

FMS total score among LBP patients and control group

The total score of FMS™ among LBP patients and the control group was available in three papers (144 patients).7,19,21 The analysis revealed that the LBP group had a significantly lower total FMS™ score than the control group by 1.81 (95% CI (-3.02, -0.59), p=0.004). In addition, a significantly high heterogeneity was found (I2= 89%, p<0.001).

Figure 1. Forest plot of FMS™ means and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

Individual FMSTM movement patterns

Three studies7,19,21 (144 patients) reported the scores of the seven FMS™ movement patterns between the patients with LBP and the control group. Of note, when tests are performed bilaterally (hurdle step, in line lunge, shoulder mobility, active straight leg raise, trunk stability push up, and rotary stability), the lower of the two scores is used for analysis, resulting in a single score for those tests.

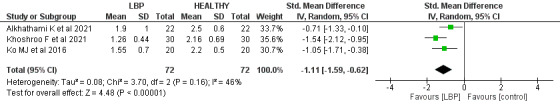

Deep squat score

There was a significant difference between the patients with LBP control group scores with SMD -1.11 (95% CI (-1.59, -0.62), p< 0.00). Low heterogeneity was found (I2= 46%, p= 0.16).

Figure 2. Forest plot of deep squat movement score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group. CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

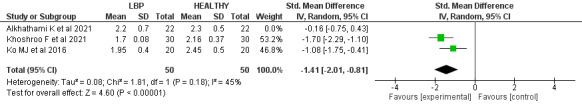

Hurdle step score

The hurdle step mean score was significantly lower in the LBP group when compared to the control group by 1.41 (95% CI (-2.01, -0.81), p< 0.001). High heterogeneity was found (I2= 85%, p<0.001). A leave-one-out test was done, the Alhathaml et al. study was removed, and the heterogeneity became (I2= 45%, p= 0.18).

Figure 3. Forest plot of hurdle steps score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

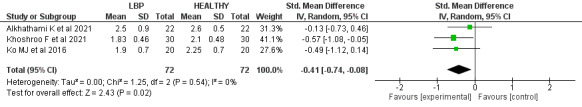

Inline lunge score

Regarding the inline lunge score, the patients with LBP had significantly lower scores than the control group, with SMD -0.41 (95% CI (- 0.74, -0.08), p=0.02). No heterogeneity was found (I2= 0%, p= 0.54).

Figure 4. Forest plot of inline lunges score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

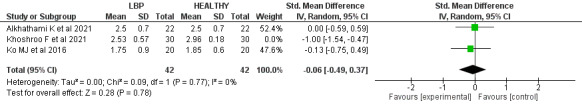

Shoulder mobility score

There was a non-significant difference in the shoulder mobility score among LBP patients and the control group, with SMD -0.39 (95% CI (-1.03, 0.25), p=0.23). Significant heterogeneity was found (I2= 73%, p-value= 0.03). A leave-one-out test was done, the Khohroo et al. study was removed, and the heterogeneity became (I2= 0%, p=0.77), and SMD became -0.06 (95% CI (-0.49, 0.37), p= 0.78).

Figure 5. Forest plot of shoulder mobility score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

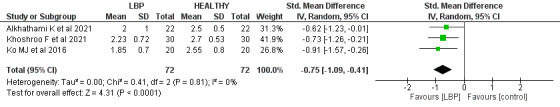

Active straight-leg raise scores

There was a significant difference between the LBP group and the controls, by SMD -0.75 (95% CI (-1.09, -0.41), p< 0.00). Furthermore, no heterogeneity was found (I2= 0%, p= 0.81).

Figure 6. Forest plot of active straight-leg raises score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

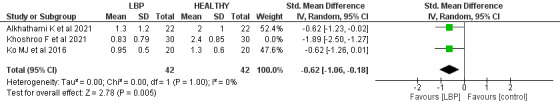

Trunk Stability Push-up score

The LBP patients reported a significantly lower score in trunk stability push-up screening than the control by SMD -1.05 (95% CI (-1.88, -0.21), p=0.01). A significant high heterogeneity was found (I2= 81%, p=0.00). A leave-one-out test was done, the Khohroo et al. study was removed, and the heterogeneity became (I2= 0%, p=1.0), and SMD became -0.62 (95% CI (-1.06, -0.18), p= 0.00).

Figure 7. Forest plot of push-up score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

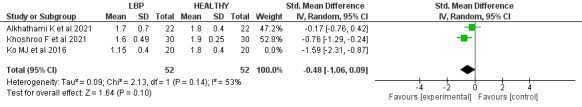

Rotatory stability score

Regarding rotatory stability, a significant difference was revealed between the scores of the patients with LBP and the control group with SMD -0.82 (95% CI (-1.56, -0.08), p=0.03). Significant heterogeneity was found (I2= 78%, p=0.01). A leave-one-out test was done, the Ko et al. study was removed, and the heterogeneity became (I2= 53%, p=0.14), and SMD became -0.48 (95% CI (-1.06, 0.09), p= 0.1).

Figure 8. Forest plot of rotatory stability score and 95% CIs, grouped by LBP and control group.

CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, LBP low back pain.

DISCUSSION

Functional movement proficiency and examining movement patterns could demonstrate the foundation for lifelong physical activity. While the FMS™ is considered a fundamental screening tool for assessing functional movement, previous research has been primarily focused on the application of FMS™ among athletes.24 This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis using the FMS™ to compare the functional movement scores among adult patients with LBP and healthy subjects. In addition, this study reviews the validity of the FMS™ tool for screening the functional movement abilities of LBP patients.

FMS™ total score

The FMS™ is a commonly utilized screening tool for evaluating functional movement, supported by experimental research conducted and synthesized to date. This research encompasses diverse populations, including youth athletes and adults of both sexes.25,26

According to the screened studies in this systematic review, the mean total score of the FMS™ among LBP patients ranged from 10.95 to 14.1.7,19,21 The mean FMS™ scores for control groups ranged from 14.40 to 16.2. The meta-analysis found that LBP patients had a significantly lower total FMS™ score than the control group by 1.81 (p-value= 0.004). These findings support the literature and suggest that LBP patients generally exhibit lower functional movement capabilities than individuals without LBP, as evidenced by their lower FMS™ scores, supporting the validity of the screening tool. These lower scores are due to these FMSTM tasks being accompanied by lower or upper extremity movement, and some patients with LBP have difficulty in properly recruiting certain muscles, such as trunk stability muscles, and often display limited hip joint mobility. This could be reflected in lower scores seen in those with LBP on the deep squat, hurdle step, ASLR, and rotary stability movements.

Individual FMS™ movement patterns scores

Deep squat score

LBP patients often demonstrate limited range of hip mobility, which may induce compensation in the lumbopelvic region during lower limb movement. According to observations, individuals with and without LBP showed unique movement patterns during forward bending.27 This observation further supports the existence of a biomechanical correlation between low back disorders and the functioning of other joints during dynamic tasks. Activities involving manual material handling and lifting have been linked to LBP.28 Among the techniques associated with these activities is the squat technique, which involves lifting with flexed knees.29 Squatting is fundamental to routine activities such as sitting down and standing up.30

In the present meta-analysis, there was a profound difference between the LBP patients and the control group by -1.11 regarding the deep squat score in the FMS™ (p< 0.00). Furthermore, the scores of the LBP patients regarding the deep squat movements ranged from 1.26 to 1.9 out of 3, which was lower than the control group, which scored from 2.16 to 2.5 out of 3. Accordingly, these findings indicate that the FMS™ can detect the deficiency in the deep squat movement among LBP patients.

Hurdle step score

The hurdle step requires appropriate stability and coordination between the hips and torso during the stepping motion. It was revealed that individuals with CLBP would demonstrate deficiencies in this movement pattern.9

The meta-analysis results found that the mean score of hurdle steps in the FMS™ was significantly lower in the LBP group compared to the control group by 1.41 (p < 0.001). Moreover, the hurdle step scores among patients with LBP had lower scores (mostly less than 2 points) ranging from 1.7, 1.95, and 2.45 out of 3 points. In comparison, the scores among control individuals ranged from 2.16, 2.3, and 2.45 (more than 2 points) out of 3 points.

The low hurdle step scores that LBP patients received highlight how restricted hip and spine mobility which may occur in LBP patients may affect this movement. In addition, these findings reveal that FMS™ is an appropriate mechanism to assess the hurdle step among LBP patients.

Inline lunge score

The inline lunge test requires ankle, knee, and hip stability in the stepping leg and controlled closed kinetic chain hip flexion. Additionally, mobility is required in hip abduction, ankle dorsiflexion, and rectus femoris flexibility of the stepping leg.

Poor performance in this test can be caused due to various factors. First, there may not be enough hip mobility in the stance or step leg. Second, the knee or ankle stability in the stance leg may be insufficient while performing the lunge. Last, in one or both hips, an imbalance between relative adductor weakness and abductor tightness OR abductor weakness and adductor tightness might contribute to poor test performance.9

The meta-analysis of the incorporated papers found that the inline lunge score in FMS™ among patients with LBP patients was significantly lower than the control group by 0.41 (p=0.02). Despite the statistical difference between the two groups, the value of the difference in score is less than 1 which clinically could be very minute. Moreover, the scores of patients with LBP on the inline lunge were somewhat similar to the control subjects’ scores (1.83 to 2.5 versus 2.1 to 2.6, respectively).

Shoulder mobility scores

According to the included studies, there was no significant difference in the score of shoulder mobility among patients with LBP and the control group by -0.06 (p=0.78). However, the negative results mean the mean score of patients with LBP is lower than control group, no significant difference was found. Furthermore the included studies, patients with LBP scored similar or lower in the shoulder mobility movement than the control group.

Active straight-leg raise score

The straight leg raise test is widely used to assess the active hamstring and gastro-soleus flexibility while preserving stability in the torso.31 Sciatica is discomfort that radiates from the buttocks to the legs and is commonly associated with LBP.32 LBP is among the most common indications for the use of the straight leg raise test.33

According to the present findings, the patients with LBP reported a score ranging from 1.85 to 2.23 out of 3, while the control group scored 2.5 to 2.77 out of 3. Moreover, there was a significant difference between the LBP group and the control one, by SMD -0.75, favoring healthy control cases (p< 0.00). However, the difference between the two groups is very low, which clinically could be very minute and may not impact the ability to distinguish adults with LBP from those without LBP.

Push-up score

The push-up movement test is commonly used to investigate upper-limb muscular fitness, especially among young people.33.34 Low fitness in the trunk stability push-up test correlates with low back dysfunction and pain among middle-aged individuals.34

In this meta-analysis, the patients with LBP had lower push-up screening scores than the control scores by 1.05 (p=0.01). In the included studies, the LBP patients reported relatively low scores in the push-up screening, ranging from 0.83 to 1.3 out of 3. Low fitness in the modified push-up test has been associated with poor perceived health, low back dysfunction, and pain among middle-aged subjects. Also, poor endurance in the back musculature has been reported to be a risk factor for LBP.35

Rotatory stability score

The rotatory stability test is performed with either lower or upper extremity movement. Shoulder flexion stimulates anterior displacement of the center of mass, placing greater demands on the trunk muscles to keep the center of mass over the base of support. Thus, trunk stability is required to sustain a neutral position. It was revealed that LBP patients have burdens that require proper recruitment of the trunk stability muscles before moving the limbs.5 Thus, compensation may occur among LBP patients during rotary stability tests due to inappropriate recruitment of the trunk stability muscles. This may lead to lower scores among LBP patients compared to healthy individuals.35–37

In this meta-analysis, there was a significant difference between the scores of the patients with LBP and the control groups by 0.82 (p-value= 0.03). However, this difference between the two groups is less than 1, which clinically could be very minute.

Limitations

This systematic review is limited to the few included studies that compare FMS™ among patients with LBP control groups. Furthermore, the review primarily focuses on adult subjects, and the generalizability of the findings to other populations, such as highly competitive and youth athletes, may be limited. Additionally, the review does not consider potential confounding factors such as pain or the influence of specific interventions or treatments on FMS™ scores. Further research is needed to assess the association of cofounders, such as age, gender, and body mass index, with the FMS™ score among LBP patients and the control group.

CONCLUSION

Low to unclear risk of bias studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis provide valuable insights for clinicians and healthcare professionals while evaluating and treating patients with LBP. Lower scores on the FMS™ tool are associated with impaired functional movement and increased injury risk among LBP patients. Further well-designed research may be more specific in the targeted population and include FMS™ in LBP within one of its various subcategories, such as acute, chronic, and non-specific cases.

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Shaqra University for supporting this work.

References

- The prevalence of low back pain: A systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. Walker B.F. 2000J Spinal Disord. 13(3):205–217. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J R, Harrelson G L, Wilk K E. Physical rehabilitation of the injured athlete: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sci; [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of pediatric sports injuries: Individual sports. Gur H. 2005J Sports Sci Med. 4(2):214. doi: 10.1159/000085330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Effective treatment of stretch step to keep changes in the face of resistance and liberation of the hip joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Kiani Dehkordi K., Ebrahim K., Frastic S. 2008J Mov Sci Sport. 2(12):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- The effects of psychosocial factors on quality of life among individuals with chronic pain. Lee G. K., Chronister J., Bishop M. 2008Rehab Couns Bull. 51(3):177–189. doi: 10.1177/0034355207311318. doi: 10.1177/0034355207311318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Core stability exercise in chronic low back pain. Hodges P. W. 2003Orthop Clin North Am. 34(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(03)00003-8. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Differences in performance on the functional movement screen between chronic low back pain patients and healthy control subjects. Ko M. J., Noh K. H., Kang M. H., Oh J. S. 2016J Phys Ther Sci. 28(7):2094–2096. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.2094. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of back pain functional scale with Roland Morris disability questionnaire, Oswestry disability index, and short form 36-health survey. Koç M., Bayar B., Bayar K. Jun 15;2018 Spine. 43(12):877–82. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002431. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pre-participation screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function - part 1. Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B. 2006N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 1(2):62–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pre-participation screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function - part 2. Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B. 2006N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 1(3):132–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional movement screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function - part 1. Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B. J., Voight M. 2014Int J Sports Phys Ther. 9(3):396–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional movement screening: The use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function-part 2. Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B. J., Voight M. 2014Int J Sports Phys Ther. 9(4):549–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional movement test scores improve following a standardized off-season intervention program in professional football players. Kiesel K., Plisky P., Butler R. 2011Scand J Med Sci Sports. 21(2):287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01038.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J. M., Akl E. A., Brennan S. E., Chou R. 2021Int J Surg. 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Sterne J. A., Hernán M. A., Reeves B. C.., et al. Oct 12;2016 BMJ. 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis in clinical trials. DerSimonian R., Laird N. 1986Control Clin Trials. 7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commentary: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Higgins J. P. Oct 1;2008 Int J Epidemiol. 37(5):1158–60. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn204. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of spinal stabilization exercises on movement performance in adults with chronic low back pain. Alkhathami K., Alshehre Y., Brizzolara K., Weber M., Wang-Price S. Feb 1;2023 Int J Sports Phys Ther. 18(1):169–172. doi: 10.26603/001c.68024. doi: 10.26603/001c.68024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reliability and validity of the Y-balance test in young adults with chronic low back pain. Alshehre Y., Alkhathami K., Brizzolara K., Weber M., Wang-Price S. 2021Int J Sports Phys Ther. 16(3):628–635. doi: 10.26603/001c.23430. doi: 10.26603/001c.23430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between chronic low back pain and physical factors in collegiate pole vaulters: A cross-sectional study. Enoki S., Kuramochi R., Murata Y., Tokutake G., Shimizu T. 2020Int J Sports Phys Ther. 15(4):537–547. doi: 10.26603/ijspt20200537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of functional movement patterns between female low back pain developers and non-pain developers. Khoshroo F., Seidi F., Rajabi R., Thomas A. 2021Work. 69(4):1247–1254. doi: 10.3233/WOR-213545. doi: 10.3233/WOR-213545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musculoskeletal screening to identify female collegiate rowers at risk for low back pain. Gonzalez S.L., Diaz A.M., Plummer H.A., Michener L.A. 2018J Athl Train. 53(12):1173–1180. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50-17. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between rowing injuries and the functional movement screen™ in female collegiate division I rowers. Clay H., Mansell J., Tierney R. 2016Int J Sports Phys Ther. 11(3):345–349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Assessment of functional movement in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. O’Brien W., Khodaverdi Z., Bolger L., Tarantino G., Philpott C., Neville R.D. 2021Sports Med. 52(1):37–53. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01529-3. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01529-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normative data for the functional movement screen in middle-aged adults. Perry F.T., Koehle M.S. 2013J Strength Cond Res. 27(2):458–462. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182576fa6. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182576fa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional movement screen normative values in a young, active population. Schneiders A.G., Davidsson A., Hörman E., Sullivan S.J. 2011Int J Sports Phys Ther. 6(2):75–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of lumbopelvic rhythm and flexion-relaxation response between 2 different low back pain subtypes. Kim M.H., Yi C.H., Kwon O.Y., et al. 2013Spine. 38(15):1260–1267. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318291b502. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318291b502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of dynamic three-dimensional trunk motion in occupationally-related low back disorders. The effects of workplace factors, trunk position, and trunk motion characteristics on risk of injury. Marras W. S., Lavender S. A., Leurgans S. E.., et al. 1993Spine. 18(5):617–628. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199304000-00015. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199304000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Similarity of different lifting techniques in trunk muscular synergies. Mirakhorlo M., Azghani M. R. 2015Acta Bioeng Biomech. 17(4):21–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squat - Rules of performing and most common mistakes. Czaprowski D., Biernat R., Kędra A. 2012Pol J Sport Tour. 19(1):3–7. doi: 10.2478/v10197-012-0001-6. doi: 10.2478/v10197-012-0001-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Extending the straight leg raise test for improved clinical evaluation of sciatica: Reliability of hip internal rotation or ankle dorsiflexion. Pesonen J., Shacklock M., Rantanen P., et al. Mar 24;2021 BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 22(1):303. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04159-y. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04159-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes among low back pain consulters with referred leg pain in primary care. Hill J.C., Konstantinou K., Egbewale B.E., Dunn K.M., Lewis M., van der Windt D. 2011Spine. 36(25):2168–2175. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820712bb. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820712bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normative health-related fitness values for children: Analysis of 85347 test results on 9-17-year-old Australians since 1985. Catley M. J., Tomkinson G. R. 2013Br J Sports Med. 47(2):98–108. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090218. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health-related fitness test battery for adults: Associations with perceived health, mobility, and back function and symptoms. Suni J. H., Oja P., Miilunpalo S. I., Pasanen M. E., Vuori I. M., Bös K. 1998Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 79(5):559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90073-9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of shoulder flexion loaded by an elastic tubing band on EMG activity of the gluteal muscles during squat exercises. Kang M. H., Jang J. H., Kim T. H., Oh J. S. 2014J Phys Ther Sci. 26(11):1787–1789. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1787. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altered trunk muscle recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds. Hodges P. W., Richardson C. A. 1999Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 80(9):1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90052-7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of abdominal bracing in combination with low extremity movements on changes in thickness of abdominal muscles and lumbar strength for low back pain. Lee S. H., Kim T. H., Lee B. H. 2014J Phys Ther Sci. 26(1):157–160. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.157. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]