Abstract

The angular gyrus (AG) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) demonstrate extensive structural and functional connectivity with the hippocampus and other core recollection network regions. Consequently, recent studies have explored neuromodulation targeting these and other regions as a potential strategy for restoring function in memory disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease. However, determining the optimal approach for neuromodulatory devices requires understanding how parameters like selected stimulation site, cognitive state during modulation, and stimulation duration influence the effects of deep brain stimulation (DBS) on electrophysiological features relevant to episodic memory. We report experimental data examining the effects of high-frequency stimulation delivered to the AG or PCC on hippocampal theta oscillations during the memory encoding (study) or retrieval (test) phases of an episodic memory task. Results showed selective enhancement of anterior hippocampal slow theta oscillations with stimulation of the AG preferentially during memory retrieval. Conversely, stimulation of the PCC attenuated slow theta oscillations. We did not observe significant behavioral effects in this (open-loop) stimulation experiment, suggesting that neuromodulation strategies targeting episodic memory performance may require more temporally precise stimulation approaches.

Keywords: Deep brain stimulation, Episodic memory, Hippocampal theta oscillations, Angular gyrus, Posterior cingulate cortex

1. Introduction

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) revolutionized the treatment of conditions like Parkinson’s Disease and Essential Tremor (Lee, Lozano, Dallapiazza, & Lozano, 2019), yet its application in memory dysfunction and cognitive disorders remains unrealized. A key obstacle is the heterogeneity in the response to stimulation across brain regions, particularly within hippocampal networks. Studies have highlighted how the physiological and behavioral effects depend on: the structure and function of target site and underlying network (Ashkan, Rogers, Bergman, & Ughratdar, 2017; Chiken & Nambu, 2016; Hermiller, Chen, Parrish, & Voss, 2020; Johnson, Kam, Tzovara, & Knight, 2020; Mohan et al., 2020), stimulation waveform and sequence parameters (Hermiller et al., 2020; Mohan et al., 2020), and the timing and dosage required to induce an effect (Ashkan et al., 2017; Freedberg et al., 2020; Phipps, Murman, & Warren, 2021; Yeh & Rose, 2019).

Furthermore, there’s yet no consensus on the ideal brain target for stimulation. Initial open–loop stimulation research suggested potential therapeutic benefit from entorhinal cortex stimulation (Suthana et al., 2012; Titiz et al., 2017), although this proved difficult to replicate in larger patient groups (Goyal et al., 2018; Hansen et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2016). Phase III trials of DBS of the fornix in Alzheimer’s patients, specifically, yielded unsuccessful results (Jakobs, Lee, & Lozano, 2020; Laxton et al., 2010; Leoutsakos et al., 2018; Lozano et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these strategies remain under investigation, and future paradigm modifications might prove effective.

The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), parahippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex, and angular gyrus (AG), demonstrate strong connectivity with the hippocampus within a conserved set of brain regions active during episodic processing termed the core recollection network. The activity of this network reflects episodic information quantity and content (Cansino, 2022; Choi et al., 2020; King, de Chastelaine, Elward, Wang, & Rugg, 2015; Thakral, Wang, & Rugg, 2017). Our lab previously examined the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) as an open-loop stimulation site (Natu et al., 2019), grounded on substantial non–invasive data demonstrating its reciprocal activity within encoding and retrieval phases of episodic memory paradigms (Daselaar, 2009; Otten & Rugg, 2001; Sestieri, Shulman, & Corbetta, 2017; Vannini et al., 2011). Our findings, however, showed open–loop stimulation of the PCC during encoding impaired memory, mirroring other open-loop paradigms (Coleshill et al., 2004; Halgren, Wilson, & Stapleton, 1985; Halgren & Wilson, 1985; Lacruz et al., 2010; Merkow et al., 2017; Weigenand, Mölle, Werner, Martinetz, & Marshall, 2016). Nevertheless, we observed that stimulation produced a consistent effect on hippocampal gamma band activity, an attribute we continue to investigate through alternative stimulation modeling approaches (Davila, Wang, Ritzer, Moran, & Lega, 2022). Given these findings, the core recollection network remains as a promising prospective stimulation target.

Concurrently, research by Voss and others has suggested that non-invasive stimulation to the temporo–parietal junction (including angular gyrus) can boost episodic memory if administered over several days, with memory effects predicted by connectivity metrics (Albouy, Weiss, Baillet, & Zatorre, 2017; Freedberg et al., 2020; Lurie, Kragel, Schuele, & Voss, 2022; Nilakantan, Bridge, Gagnon, VanHaerents, & Voss, 2017; Wang et al., 2014). Leveraging our prior exploration of core recollection network targets for stimulation mapping (Choi et al., 2020), we assessed the impact of DBS (via intracranial depth electrodes) applied to the AG versus PCC. We also compared outcomes between stimulation during the encoding versus retrieval phases of a free recall task. Our investigations aimed to discern: (1) variations in electrophysiological or behavioral outcomes from stimulating different core recollection network targets, (2) the dependency of these effects on the phase of the memory paradigm in which stimulation is delivered, (3) the potential for theta oscillation enhancement with specific parameters, (4) the temporal evolution of stimulation effects, (5) hemispheric and longitudinal differences in electrophysiological changes, and (6) the correlation of these effects with theta connectivity between hippocampus and stimulation target site (measured separately from stimulation paradigms).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Patients undergoing stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) monitoring for pharmacoresistant epilepsy at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center agreed to participate in this study and provided written informed consent. Protocols were approved by the institution’s Internal Review Board as part of its Human Research Protection Program. Our analysis included 62 participants (32 female) with hippocampal depth electrode contacts, who completed a free recall task with DBS targeting PCC or AG. For consideration in enrollment, patients needed to be 18 years of age or older. A priori exclusion criteria encompassed pregnancy, incarceration, or a diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

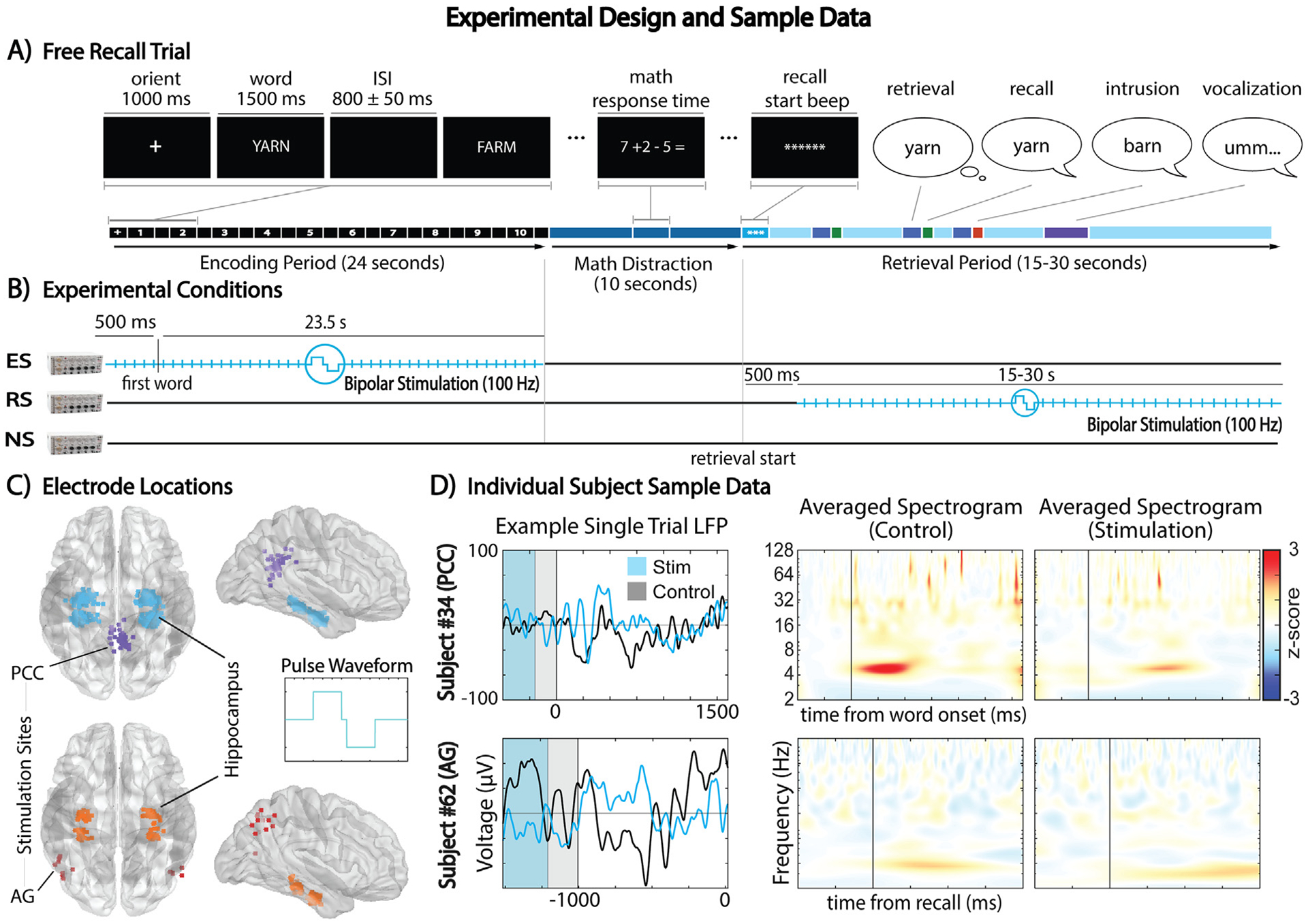

Fig. 1C shows how patients were divided into groups based on the DBS target: AG (NAG = 13; 5 left AG, 8 right AG; ages 20–54) and PCC (NPCC = 49; 38 left PCC, 11 right PCC; ages 20–64). AG participants had 85 hippocampal contacts in total (average 6.5 [2.4] per subject), while PCC subjects had 354 (average 7.2 [2.9] per subject). Table A.1 details participant demographics.

Fig. 1 –

Overview of the experimental design and sample data for DBS during free recall tasks. (A) Schematic representation of a free recall trial, detailing the encoding, math distraction, and retrieval phases. (B) Illustration of the three experimental conditions: Encoding Stimulation (ES), Retrieval Stimulation (RS), and No Stimulation (NS), along with the onset and duration of stimulation. (C) Electrode contact locations, highlighting the stimulated PCC and AG contacts, and their corresponding hippocampal channels. 300 μs-wide bipolar square pulses separated by a 55 μs interphase were delivered at 100Hz with an amplitude of 2 mA. (D) Sample data from individual subjects, comparing stimulation and control conditions during encoding (top) and retrieval (bottom), depicted in single–trial low–pass filtered LFPs and trial–averaged, baseline–normalized spectrograms.

Group matching analyses were performed by using Fisher’s Exact Test on group proportions for several demographics and epilepsy etiologies. Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare age and duration of epilepsy, and hippocampal contact counts (total and fraction labeled as ictal or interictal), between groups. Preoperative neuropsychometric reports varied in score format and tests included among subjects, and thus scores were converted to range descriptors for all subjects and Mann–Whitney U Test was used to compare scores between groups. Score range descriptors for Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test and California’s Verbal Learning Test were aggregated for this analysis.

2.2. Electrode localization

An expert neurologist manually localized the electrodes as part of standard clinical practice. Preoperative T1 MRI and postoperative CT images were processed and fused using software including MRIcron (Rorden & Brett, 2000), FSL (Smith et al., 2004), and FreeSurfer (Fischl, 2012); to identify depth electrode anatomical locations and determine their co-ordinates after standardizing imaging to Montreal Neurological Institute space (Evans et al., 1993).

2.3. Experimental design

Fig. 1 depicts the experimental design. Similar to previous research (Ezzyat et al., 2017; Goyal et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2016; Natu et al., 2019), participants performed a verbal free recall task, memorizing sequential lists of 10 nouns randomly selected from the word pool developed by the University of Pennsylvania for the Restoring Active Memory program (Kahana, 2023). These nouns were read aloud during the encoding (study) phase of the task. Fig. 1A shows that each noun was displayed for 1500 msec with an 800 ± 50 msec jittered inter–stimulus interval. A simple arithmetic math distraction task lasting 10 sec preceded the retrieval (test) phase. Participants had 15–30 sec to attempt recall of as many nouns from the list in any order. Retrieval phase duration varied between subjects (summarized in Table A.2).

The experiment included three conditions (Fig. 1B): encoding DBS (ES), retrieval DBS (RS), and no stimulation (NS). ES and RS lasted for the entirety of their respective periods, starting 500 msec before the first word onset during the encoding phase, and 500 msec after the start–signaling beep of the retrieval phase. A Grass S88 stimulator delivered 100 Hz, charge–balanced, biphasic, square pulses in bipolar mode via paired target site contacts: with 2 mA amplitude (1.5 mA for 7 PCC subjects), 300 μs pulse width, and 55 μs interphase. Both subjects and researchers were blind to the condition. Ten trials per condition were interleaved in each session. AG group’s experimental sessions included all conditions; PCC group’s condition inclusion varied (Table A.2). Throughout the experimental sessions, depth electrode signals were acquired at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz using Nihon Kohden’s 2100 clinical system.

2.4. Behavioral analysis

Similar to prior work (Natu et al., 2019) we tested the behavioral effects of DBS on a reduced list of 47 subjects (13 AG, 34 PCC) whose experimental sessions also included a control condition (‘NS’). Effects of encoding and retrieval stimulation conditions were tested separately by only comparing trials specific to these conditions with control trials. Linear Mixed Effects Modeling (LMEM) from MATLAB’s statistical toolbox (MathWorks, 2021) was used to measure the effect of stimulation condition and its interaction with stimulation group on: number of words recalled for every list, total number of intrusions across the task (aggregating prior–list and extra–list intrusions), percent recall by serial position, temporal and semantic clustering factors (TCF and SCF), and lag–conditional response probability (lag–CRP). Eq. B.1–3 detail the fixed and random effects of each behavioral metric’s model. This study utilized two-tailed tests for all statistical analyses, ensuring no presupposed direction of the effects was assumed. Statistical tests for all analyses were all corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini–Hochberg correction. Degrees of freedom for all analyses were calculated using Satterthwaite’s approximation method.

2.5. Electrophysiological analysis

Hippocampal contact local field potentials (LFPs) were referenced to corresponding depth electrode contacts located in white matter (or to the next adjacent gray matter contact, if unavailable). LFPs were notch–filtered for stimulation and power–line noise frequencies (60 and 100Hz, respectively, and all harmonics below Nyquist frequency of 500 Hz). Motion and blinking artifacts were reduced by rejecting trials exceeding either a kurtosis threshold of 4 or the 95th percentile of root–median–square deviations. Electrode contacts were also excluded if the normalized power values exceeded 3 standards deviations from the mean across electrodes. Contacts with half or more trial exclusions, or sessions with half or more contact exclusions were removed from all analyses (Table A.2).

Instantaneous phase and power were calculated for 57 log-spaced frequencies between 2 and 256 Hz using Morlet Wavelet Convolution (width of 6 cycles). For item encoding, power was calculated for 1600 msec following word onset and for a baseline 500 to 200 msec prior to it. For item retrieval, power was calculated for 1000 msec preceding recall and for a baseline 1500 to 1200 msec prior to it. Power was normalized as a percent change from the mean baseline power of trials without stimulation. In subjects without a control (NS) condition, the mean baseline of trials without active stimulation in the corresponding period analyzed was used.

Median power values across trials were gathered per electrode and condition at each time–frequency step for LMEM analyses comparing power between conditions and target stimulation regions (Eq. B.4–5). Only subjects with relevant experimental conditions (ES for encoding or RS for retrieval) and a control (NS) were included in the analysis of a given period, and only data specific to the experimental condition and control were input to the models. The effects were modeled separately for hippocampal contacts in the same hemisphere as stimulation site (ipsilateral) and the opposite hemisphere (contralateral), with random effects accounting for subject, electrode, and stimulation hemisphere variances. Hippocampal contacts were pooled as ipsilateral and contralateral to stimulation site to maximize statistical power.

We contrasted the electrophysiological effects of stimulation during encoding versus retrieval using LMEM (Eq. B.6). For every encoding and retrieval trial, and for all measured frequencies, we obtained the mean power across the respective trial’s entire duration (1600 msec for encoding, 1000 msec for retrieval). We assigned the label ‘stimulation’ to trials with active stimulation in the period of interest (ES for encoding trials, RS for retrieval trials), and ‘no stimulation’ to remaining trials (NS or RS for encoding, NS or ES for retrieval). This was exclusively done in this analysis to incorporate data from the subset of PCC subjects who had no control (NS) condition. Compared to above, this model encompasses more observations since it includes all trial data (vs the median across trials). Ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal contacts were modeled separately.

Furthermore, encoding and retrieval paradigm phases were divided into five segments. Mean power across time within the first and last segments (“early” and “late” in Fig. 4) was obtained for every trial. The interaction between time segment and experimental condition was assessed using LMEM (Eq. B.7–8) to determine the impact of time on stimulation effects. We only considered the first 15 sec of the retrieval phase for consistency in duration across subjects. Only subjects with a control condition were included in this analysis. Ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal contacts were input into separate models.

Fig. 4 –

Temporal evolution of electrophysiological changes in the anterior hippocampus. (A) Progressive enhancement of ipsilateral slow theta power due to AG stimulation during encoding (p < .05, highlighted in first row, third column). (B) No significant time–dependent change in contralateral slow theta power influenced by AG and PCC stimulations during encoding. (C) Diminishing effect of PCC stimulation on ipsilateral slow theta power reduction during retrieval (highlighted in second row, third column). (D) Increasingly positive impact of AG stimulation on contralateral slow theta power during retrieval (highlighted in first row, third column).

Additionally, for all item encoding and retrieval trials we obtained the mean power within the slow theta frequency band (2–4 Hz) and across the period of the trial. We then pooled ipsilateral and contralateral contacts from each stimulation group. For separate models, we labeled power values based on the long–axis location (anterior and posterior) or hemisphere (left and right) of the corresponding hippocampal contact. We then modeled the interaction between these categories and experimental conditions to assess for anatomical variation in stimulation effect (Eq. B.9–10).

2.6. Connectivity analysis

The hardware setup used to deliver DBS did not allow for simultaneous recording and stimulation of target site. Not all participants completed a (non–stimulation) antecedent free recall task with recording of target site. The subset of participants who did (NAG = 7 subjects, 52 hippocampal contacts; NPCC = 37 subjects, 274 contacts) were included in connectivity analyses. For this analysis, inter–site phase clustering values were calculated to estimate connectivity between hippocampal contacts and the prospective stimulation target site. For each time-frequency step of item encoding and retrieval, phase differences between hippocampus and stimulation target site were transformed into the complex plane and the magnitude of the mean vector across trials was obtained. For each hippocampal electrode we obtained the mean inter–site phase clustering values and magnitude of stimulation effect on power (t-statistic) within slow theta frequency band (2–4 Hz). Then, for each subject we averaged across hippocampal electrodes to obtain a single value for both measurements, and their relationship was analyzed using Spearman’s Rank Correlation.

Furthermore, for each stimulation site we obtained a t-statistic representing the site’s slow theta response during encoding and retrieval trials. This t-statistic was calculated by performing a Paired Samples T-test between mean power values of each trial and their corresponding baseline period. Similarly to above correlation analysis, we obtained the mean slow theta inter-site phase clustering values across hippocampal electrodes, and we analyzed their relationship with stimulation site slow theta activity using Spearman’s Rank Correlation.

2.7. Spectral analysis and oscillation detection

Power spectra properties were analyzed and oscillations in EEG segments were detected by band-passing LFPs between 2 and 28 Hz (1600 msec following word onset in encoding, 1000 msec prior to recall in retrieval, with flanking 2000 msec buffers). We used Morlet Wavelet Convolution to calculate power for these frequencies. After removing the buffer, the mean across time was calculated to generate power spectra. The aperiodic and periodic components of the spectra were parameterized using the FOOOF algorithm (1.0.1) (Kosciessa, Grandy, Garrett, & Werkle-Bergner, 2020). The algorithm detected an unconstrained number of periodic peaks with a width of .3–24 Hz that exceeded a threshold of one standard deviation of power after removing the aperiodic component (this fitted with a knee). These setting were used to maximize detections and minimize fitting error in the theta range. We used an LMEM model (Eq. B.11) to contrast the aperiodic fit exponent (power spectrum slope in log–log space) between conditions. In a similar manner, we also performed oscillation detection for stimulation sites, using LFPs from the stimulation–devoid task.

Moreover, we used the mean across trials of log-transformed power spectra to fit the aperiodic component more accurately. This fit was multiplied by the 90th percentile of the chi-square distribution function (2 degrees of freedom) to determine the power threshold used in the fBOSC algorithm (Seymour, Alexander, & Maguire, 2022; Whitten, Hughes, Dickson, & Caplan, 2011). To detect a potential oscillation in every trial, power values derived from wavelet convolution needed to exceed this threshold for a total duration of more than 3 cycles (frequency specific). The p-episode for each trial was calculated as the fraction of the encoding or retrieval period exceeding the power threshold.

2.8. Transparency and data access

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all inclusion/exclusion criteria, whether inclusion/exclusion criteria were established prior to data analysis, all manipulations, and all measures in the study. Study data is not publicly archived and is privacy protected in compliance with protocol approved by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board. Study data is available upon reasonable request by sending an email to the principal investigator (Bradley.Lega@UTSouthwestern.edu). The code used to perform the analyses presented in this paper (https://github.com/eugenio-forbes/pyFR_stim_analysis/tree/main/code), as well as the free recall task code and word pool used (https://github.com/eugenio-forbes/pyFR_stim_analysis/tree/main/task ), are all publicly available in the Github repository of the first author (https://github.com/eugenio-forbes/pyFR_stim_analysis). No part of the study procedures or study analysis were preregistered in a time-stamped institutional registry prior to the research being conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of deep brain stimulation on behavioral performance metrics of free recall

We separately compared behavioral metrics of both experimental conditions’ trials (‘ES’, ‘RS’) with those of control trials (‘NS’) using LMEM (Eq. B.1–3). Fig. 2 illustrates the behavioral results of the study. We observed a non-significant (p < .05) decrease in total number of intrusions across trials (aggregated prior–list and extra–list intrusions) (t(13.0) = −1.86, corrected p = .57) and a non-significant increase in semantic clustering (t(11.7) = 2.07, corrected p = .57) from stimulating the angular gyrus during retrieval. Stimulation of the PCC during encoding resulted in a non-significant increase in temporal clustering (t(39.7) = 2.25, corrected p = .60). Correction for multiple comparisons, thus, revealed that there were no significant differences in behavioral performance metrics of free recall within or between groups from stimulation during encoding or retrieval. Fig. 2E, F illustrate how throughout performance of the free recall task participants exhibited primacy and recency effects, as well as forward asymmetry. There were however no differential stimulation effects on percent recall between primacy and non-primacy items (Eq. B.3). Between-group demographic data and control trial comparisons demonstrating no significant differences in baseline memory function and disease are described in Tables A.3–8.

Fig. 2 –

Effects of deep brain stimulation on behavioral performance metrics of free recall. Correction for multiple comparisons reveled no statistically significant differences in behavioral performance metrics of free recall within or between groups from stimulation during encoding or retrieval.

3.2. Electrophysiological changes induced by stimulation

In this analysis, we primarily examine stimulation–induced modulations in the anterior hippocampus, as there was more consistent inclusion of both parietal and anterior hippocampal recording sites in our data set (265 anterior electrode contacts from all 62 subjects vs 229 posterior contacts from 55 subjects). We focused on the impact of stimulation on slow theta (2–4 Hz) power, given our previous findings of memory–related power changes in this band as compared to fast theta (4–8 Hz) frequencies (Lega, Jacobs, & Kahana, 2012; Pastötter and Bäuml, 2014; Lega, Burke, Jacobs, & Kahana, 2016; Lega, Germi, & Rugg, 2017; Lin et al., 2017; Goyal et al., 2020; Jun et al., 2020; Kota, Rugg, & Lega, 2020). We also compared ipsilateral versus contralateral stimulation–related effects.

Fig. 3 illustrates the comparison of electrophysiological effects between target stimulation sites, task phases, and location relative to stimulation site. Our results revealed significant (p < .05) increases in slow theta (2–4 Hz) power within the anterior hippocampus (both ipsilateral and contralateral to stimulation target) when the angular gyrus was stimulated during item retrieval (Fig. 3A). These effects were observed 800–460 msec before item recall at 3–4 Hz and 230–0 msec at 2–3 Hz for ipsilateral contacts; and 590–500 msec at 4Hz for contralateral contacts. In contrast, PCC stimulation elicited significant decreases in slow theta power during retrieval with a similar pattern during encoding. This effect was particularly evident for hippocampal contacts ipsilateral to the stimulation site, maintaining significance after correction for a full second before item recall at 2–3 Hz. Comparing the PCC stimulation effect by task phase (retrieval vs encoding) revealed that the effect of stimulation was significantly greater for retrieval (Fig. 3B). Comparing the stimulation effect by region revealed that AG stimulation had a more positive influence on slow theta power than PCC stimulation, with a significant contrast 740–360 msec before recall at 3–4 Hz (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3 –

Stimulation-induced electrophysiological changes in the anterior hippocampus and comparison between target stimulation sites and task periods. (A) Following Benjamini–Hochberg correction there were significant (p < .05) increases in slow theta power of both anterior ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal contacts from stimulating the angular gyrus during retrieval (highlighted in black in time-frequency plots). (B) In contrast, there was a significant decrease in ipsilateral anterior hippocampus slow theta power throughout retrieval from stimulating the PCC (highlighted in white). This effect was significantly greater during retrieval compared to encoding (highlighted in green in period contrast bar plots). (C) For ipsilateral anterior hippocampus contacts, the effect of stimulation on slow theta during retrieval was significantly greater for the AG group compared to the PCC group, maintaining significance after correction for 380 msec (highlighted in black in time-frequency plot, and in orange in group–level average plot).

Combined, our results demonstrate that the effect of DBS on anterior hippocampal slow theta oscillations is (1) dependent on the selected stimulation target of the core recollection network, location relative to stimulation site, and the phase of the memory task at the moment of stimulation; and (2) enhancement of this electrophysiological marker is possible with stimulation of the AG during retrieval.

3.3. Temporal dynamics of stimulation–induced oscillatory power changes

Fig. 4 illustrates the results of comparing the electrophysiological effects of stimulation between early and late segments of the encoding and retrieval phases of the memory paradigm. We emphasize that simulation was applied over the entire encoding/retrieval blocks (20 sec), which is unique as compared to other mnemonic neuromodulation strategies. Our results showed that the effects of stimulation on oscillatory power were not constant throughout these phases, but rather fluctuated over time.

Specifically, for anterior hippocampal contacts contralateral to the stimulation site, slow theta power increases seen during item retrieval from AG stimulation tended to become stronger (t(513.1) = 2.25, p = .03) towards the latter portion of the retrieval phase (Fig. 4D). Additionally for the AG group, for anterior hippocampal contacts ipsilateral to the stimulation site, we observed a significant tendency (t(241.1) = 2.40, p = .02) for the slow theta effect to become positive towards the later portion of the encoding phase (Fig. 4A).

In contrast, for PCC stimulation, the decreases in slow theta power observed in ipsilateral contacts during item retrieval tended to weaken (t(441.4) = 2.46, p = .02) towards the later portion of the retrieval phase (Fig. 4C).

3.4. Anatomical variation in hippocampal slow theta oscillatory power changes

We then sought to compare stimulation–induced changes in slow theta power between hemispheres and longitudinal axis subdivisions of the hippocampus. To maximize statistical power, we pooled together hippocampal contacts disregarding their location relative to stimulation site (ipsilateral/contralateral). LMEM (Eq. B.9–10) revealed significant (t(11.4) = 3.27, corrected p = .03) increases of slow theta power in anterior hippocampal contacts when simulating the angular gyrus during retrieval. These effects were significantly greater when comparing anterior versus posterior contacts (t(67.9) = 3.80, corrected p < .001).

While there were no significant differences in the magnitude of effects between hemispheres from stimulation of PCC, a binomial test demonstrates that a significant majority of hippocampal contacts (63.2%, p < .001) exhibited slow theta decreases. This majority stemmed predominantly from anterior contacts (64.3%, p < .001) (See Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 –

Anatomical variation in hippocampal slow theta (2–4 Hz) oscillatory power changes. (A) No significant hemispheric or longitudinal axis differences in effects from stimulating AG during encoding. (B) Anterior hippocampal contacts had significant increases in slow theta power stimulating angular gyrus during retrieval (t(11.4) = 3.27, corrected p = .03), and there were also significant interaction showing the effects were more positive for anterior versus posterior contacts (t(67.9) = 3.80, corrected p < .001). (C) LMEM revealed no significant hemispheric or longitudinal axis differences from stimulating PCC during encoding. Nevertheless, a significant majority of all hippocampal contacts exhibited decreases in slow theta power (63.2%, p < .001). No significant hemispheric or longitudinal axis differences in effects from stimulating PCC during retrieval.

3.5. Band–specific correlations of power changes with target site connectivity

Using Spearman’s Rank Correlation, we explored the relationship between baseline stimulation site slow theta connectivity with the hippocampus, and the magnitude of the stimulation effect on slow theta power. Supplemental Fig. C.6 illustrates the results. After performing Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons we found no significant (p < .05) correlations for no stimulation group, hippocampal anatomical subdivision, or task phase.

3.6. Properties of power spectra and oscillation detection of the anterior hippocampus

Supplemental Fig. C.7 shows results of comparing spectral properties and oscillation detection of the anterior hippocampus between stimulation and control trials after pooling ipsilateral and contralateral electrodes. There were no significant differences from stimulation in the slopes of the spectra. Both FOOOF and fBOSC algorithms yielded oscillation detection distributions with local maxima near 3 and 8 Hz for all subject groups, experimental conditions, and task periods.

3.7. Stimulation site baseline slow theta activity

Supplemental Fig. C.8 illustrates the stimulation sites’ baseline theta activity. For all subject groups we observed variability between subjects in the magnitude and direction of slow theta activity during encoding or retrieval. FOOOF algorithm yielded oscillation detection distributions with local maxima near 3 and 8 Hz for all groups and task phases. There were no significant correlations between baseline stimulation site theta activity and its effective connectivity with anterior hippocampal contacts.

4. Discussion

Our investigation reveals that DBS targeting key extra-temporal nodes within the core recollection network, AG and PCC, can effectively modulate hippocampal slow theta oscillatory power, a prominent biomarker in episodic memory research (Lega et al., 2012; Pastötter and Bäuml, 2014; Lega et al., 2016; Lega et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2017; Goyal et al., 2020; Jun et al., 2020; Kota et al., 2020) Furthermore, the magnitude and direction of this modulation depend on the stimulated network node, targeted cognitive state, stimulation duration, and location relative to stimulation site. Consequently, our findings offer insights for developing targeted DBS therapies designed to enhance this biomarker.

Previous studies using fMRI and lesion analyses have suggested that the AG plays a crucial role in the integration of multimodal features and vividness of recollection in episodic memory (Ciaramelli et al., 2017; Simons, Peers, Mazuz, Berryhill, & Olson, 2010; Tibon, Fuhrmann, Levy, Simons, & Henson, 2019). AG–targeted transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies demonstrating disruption of multimodal associative memory and autobiographical recall (Bonnici, Cheke, Green, FitzGerald, & Simons, 2018; Yazar, Bergstrom, & Simons, 2017) and improvements in recall precision (Nilakantan et al., 2017) support this hypothesis. Although there were no significant behavioral effects from stimulating AG or PCC during encoding or retrieval, the observed decreases in number of intrusions from AG stimulation may be consistent with the proposed role of recall precision. Other studies have suggested these behavioral changes might be explained by enhanced connectivity between AG and hippocampus(Hermiller, VanHaerents, Raij, & Voss, 2018; Wang et al., 2014). Future DBS studies could analyze stimulation-induced changes in connectivity using systems that can simultaneously record and stimulate a specific channel.

In this expanded data set that incorporates modulation in both encoding and retrieval phases, stimulation of the PCC elicited some preliminary evidence of increases in temporal clustering, consistent with our previously published results (Natu et al., 2019). However, with current data, the overall behavioral effects of stimulation did not reach significance with the appropriately rigorous statistical approaches we employed. This may reflect the relatively larger proportion of right hemisphere stimulation sites; these may exhibit stronger effects for spatial navigation paradigms (Kessels, de Haan, Kappelle, & Postma, 2001; Miller et al., 2018; Spiers, 2001) or not have an effect in memory of verbal stimuli (Epstein, Sekino, Yamaguchi, Kamiya, & Ueno, 2002; Floel, 2004; Wagner et al., 1998). Furthermore, recent studies of both target sites have revealed hemispheric differences and substructure heterogeneity in function (Aponik-Gremillion et al., 2022; Busler, 2019; Kobayashi & Amaral, 2007; Seghier, 2012, 2022), that could explain the observed variability in individual performance changes. Alternatively, it may suggest the need for bilateral stimulation delivery to produce a significant effect (Simons et al., 2010). Also, we note that salubrious stimulation may require relatively prolonged stimulation epochs to achieve ‘circuit modulation’ effects, as suggested by experience using deep brain stimulation for movement disorders (Ashkan et al., 2017).

We focused our analysis on hippocampal slow theta oscillations based on the established importance of theta rhythms to intra– and inter–regional coordination during episodic processing (Buzsáaki, 2002; Nunez & Buno, 2021; Takeuchi et al., 2021). Our data demonstrate the potential for lateral parietal stimulation to modulate this biomarker of episodic processing. However, our findings show that open-loop enhancement of hippocampal slow theta activity by itself is not a sufficient condition for memory enhancement. Thus, these results suggest that stimulation of the AG or PCC may affect other mnemonically-relevant biomarkers in a way that attenuates the behavioral effects associated with slow theta; and would highlight the importance of identifying network level features that, in conjunction with hippocampal slow theta, could better explain the results. Another potential conclusion of our findings is that neuromodulation options may need to consider the precise temporal dynamics of theta power changes during episodic processing, as these changes occur during specific time windows during retrieval (Kota et al., 2020). Moreover, the distinct effects observed within and between stimulation groups emphasize the potential need for combination approaches that consider patient–specific biomarkers, with different target brain regions employed to achieve complementary behavioral effects. Future research should investigate the combined effects of stimulation on other episodic memory biomarkers, such as network connectivity measures, to better understand observed behavioral changes. Nevertheless, our results align with network control theory analysis (Gu et al., 2015) predicting a negative impact on overall network functioning from PCC alterations and less significant impacts from those involving AG.

We sought understanding of how specific cognitive states (encoding vs retrieving a memory) may impact the effect of stimulation on hippocampal oscillations. The encoding/retrieval differentiation we observed is unsurprising since we expect stimulation to act on a ‘scaffold’ of underlying neural dynamics driven by task demands (Miniussi, Harris, & Ruzzoli, 2013; Romei, Thut, & Silvanto, 2016; Rossi & Rossini, 2004; Yeh & Rose, 2019). fMRI investigations have demonstrated differences in the activity of the core recollection network among different cognitive processes (Romei et al., 2016; Silvanto, Muggleton, & Walsh, 2008). Specific to these differences, studies have reported divergence in the engagement of posterior parietal regions (Daselaar, 2009; Hutchinson, Uncapher, & Wagner, 2009; Jablonowski & Rose, 2022; Lega et al., 2017; Sestieri et al., 2017; Tibon et al., 2019; Vannini et al., 2011). Our results demonstrating variability of baseline stimulation site theta activity during encoding and retrieval align with these studies. Thus, the dissimilar electrophysiological outcomes from stimulating during encoding versus retrieval support the notion that underlying network dynamics influence stimulation outcomes specifically in episodic processing. Additionally, our results align with a study showing that microstimulation–induced network edge excitability suppression depends on a modulator’s baseline state (Qiao, Sedillo, Brown, Ferrentino, & Pesaran, 2020). Our data could thus help define ideal target cognitive states for effective neuromodulation strategies.

Another novel aspect of our analysis was the relatively extended stimulation epochs we employed, as compared to item–by–item stimulation approaches employed in other experiments related to episodic processing (Goyal et al., 2018; Jacobs et al., 2016). Our findings reveal that stimulation effects include relevant temporal dynamics across the scale of seconds, which align with prior studies (Ashkan et al., 2017; Freedberg et al., 2020; Phipps et al., 2021; Yeh & Rose, 2019). These findings would be useful in defining parameters for stimulation duration in future neuromodulatory strategies, since they suggest that a longer stimulation duration of the angular gyrus is more conducive towards increases in slow theta. Moreover, the observed temporal variations in electrophysiological effects may indicate distinct mechanisms underlying stimulation efficacy, consistent with studies exploring the need for varying stimulation durations in the treatment of different diseases (Ashkan et al., 2017; Nilakantan et al., 2017). Alternatively, these differences may reflect temporal dynamics of AG and PCC activity during encoding and retrieval, which may not be fully captured by fMRI’s lower temporal resolution (He & Liu, 2008; Lega et al., 2017). Future neuromodulation efforts should further investigate and incorporate these spatiotemporal dynamics and their relevance to episodic memory.

Finally, in our study our results did not find that baseline stimulation site connectivity with the hippocampus was predictive of the effect of stimulation on slow theta power, in contrast with prior studies (Hermiller et al., 2020; Lurie et al., 2022; Natu et al., 2019; Solomon et al., 2018). Our results are limited by the lack of simultaneous recording and stimulation of target site within the experimental session in which stimulation took place, which could more effectively test for a relationship between these two measures. More sensitive identification of connectivity patterns, potentially using directed networks or graph structures, may reveal more robust prediction of stimulation effects. Future studies would benefit from exploring this and other biomarkers that could predict response to therapy or guide patient–specific approaches to therapy.

5. Conclusion

Our study has shown that DBS of the AG and PCC during the execution of distinct cognitive processes can modulate hippocampal slow theta oscillatory power, a crucial biomarker for episodic memory. The observed differences in outcomes, based on target selection and the active cognitive process during stimulation, provide valuable insights that may contribute to the development of more effective DBS therapies aimed at augmenting this biomarker. These findings also prompt further investigation into the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed contrasts. To advance our understanding and optimize therapeutic approaches, future studies should delve into these mechanisms and examine the effects on other biomarkers implicated in episodic memory.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke-National Institutes of Health (Grant R01 NS107357-02 to B.L.).

Abbreviations:

- AG

angular gyrus

- DBS

deep brain stimulation

- ES

encoding DBS

- lag–CRP

lag-conditional response probability

- LFP

local field potential

- LMEM

linear mixed effects modeling

- NS

no DBS

- PCC

posterior cingulate cortex

- RS

retrieval DBS

- SCF

semantic clustering factor

- sEEG

stereoelectroencephalography

- TCF

temporal clustering factor

Footnotes

Open practices

The study in this article has earned Open Materials badge for transparent practices. The data and materials used in this study are available at: https://github.com/eugenio-forbes/pyFR_stim_analysis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Eugenio Forbes: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alexa Hassien: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ryan Joseph Tan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Investigation. David Wang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Bradley Lega: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2024.03.010.

REFERENCES

- Albouy P, Weiss A, Baillet S, & Zatorre RJ (2017). Selective entrainment of theta oscillations in the dorsal stream causally enhances auditory working memory performance. Neuron, 94(1). 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponik-Gremillion L, Chen YY, Bartoli E, Koslov SR, Rey HG, Weiner KS, et al. (2022). Distinct population and single-neuron selectivity for executive and episodic processing in human dorsal posterior cingulate. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.05.13.491864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkan K, Rogers P, Bergman H, & Ughratdar I (2017). Insights into the mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Nature Reviews. Neurology, 13(9), 548–554. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.105. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28752857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnici HM, Cheke LG, Green DAE, FitzGerald T, & Simons JS (2018). Specifying a causal role for angular gyrus in autobiographical memory. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38(49), 10438–10443. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1239-18.2018. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30355636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busler JN (2019). Differential functional patterns of the human posterior cingulate cortex during activation and deactivation. Experimental Brain Research, 237(9), 2367–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáaki G (2002). Theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Neuron, 33(3), 325–340. 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00586-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino S (2022). Brain connectivity changes associated with episodic recollection decline in aging: A review of FMRI studies. 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1012870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiken S, & Nambu A (2016). Mechanism of deep brain stimulation: Inhibition, excitation, or disruption? The Neuroscientist: a Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry, 22(3), 313–322. 10.1177/1073858415581986. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25888630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K, Bagen L, Robinson L, Umbach G, Rugg M, & Lega B (2020). Longitudinal differences in human hippocampal connectivity during episodic memory processing. Cerebral Cortex Communications, 1(1). 10.1093/texcom/tgaa010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciaramelli E, Faggi G, Scarpazza C, Mattioli F, Spaniol J, Ghetti S, et al. (2017). Subjective recollection independent from multifeatural context retrieval following damage to the posterior parietal cortex. Cortex; a Journal Devoted To the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 91, 114–125. 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.03.015. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28449939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleshill SG, Binnie CD, Morris RG, Alarco n G, van Emde Boas W, Velis DN, et al. (2004). Material-specific recognition memory deficits elicited by unilateral hippocampal electrical stimulation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 24(7), 1612–1616. 10.1523/jneurosci.4352-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM (2009). Posterior midline and ventral parietal activity is associated with retrieval success and encoding failure. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3. 10.3389/neuro.09.013.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila CE, Wang DX, Ritzer M, Moran R, & Lega BC (2022). A control theoretical system for modulating hippocampal gamma oscillations using stimulation of the posterior cingulate cortex. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 30, 2242–2253. 10.1109/tnsre.2022.3192170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CM, Sekino M, Yamaguchi K, Kamiya S, & Ueno S (2002). Asymmetries of prefrontal cortex in human episodic memory: Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on learning abstract patterns. Neuroscience Letters, 320(1–2), 5–8. 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02573-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A, Collins D, Mills S, Brown E, Kelly R, & Peters T (1993). 3d statistical neuroanatomical models from 305 MRI volumes. In 1993 IEEE conference record nuclear science symposium and medical imaging conference (Vol. 3, pp. 1813–1817). 10.1109/NSSMIC.1993.373602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzyat Y, Kragel JE, Burke JF, Levy DF, Lyalenko A, Wanda P, et al. (2017). Direct brain stimulation modulates encoding states and memory performance in humans. Current Biology, 27(9), 1251–1258. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.028. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28434860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B (2012). Freesurfer. NeuroImage, 62(2), 774–781. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floel A (2004). Prefrontal cortex asymmetry for memory encoding of words and abstract shapes. Cerebral Cortex, 14(4), 404–409. 10.1093/cercor/bhh002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg M, Reeves JA, Toader AC, Hermiller MS, Kim E, Haubenberger D, et al. (2020). Optimizing hippocampal-cortical network modulation via repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: A dose-finding study using the continual reassessment method. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, 23(3), 366–372. 10.1111/ner.13052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A, Miller J, Qasim SE, Watrous AJ, Zhang H, Stein JM, et al. (2020). Functionally distinct high and low theta oscillations in the human hippocampus. Nature Communications, 11(1), 2469. 10.1038/s41467-020-15670-6. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32424312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A, Miller J, Watrous AJ, Lee SA, Coffey T, Sperling MR, et al. (2018). Electrical stimulation in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex impairs spatial and temporal memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(19), 4471–4481. 10.1523/Jneurosci.3049-17.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S, Pasqualetti F, Cieslak M, Telesford QK, Yu AB, Kahn AE, et al. (2015). Controllability of structural brain networks. Nature Communications, 6, 8414. 10.1038/ncomms9414. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26423222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, & Wilson CL (1985). Recall deficits produced by afterdischarges in the human hippocampal formation and amygdala. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 61(5), 375–380. 10.1016/0013-4694(85)91028-4. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2412789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgren E, Wilson CL, & Stapleton JM (1985). Human medial temporal-lobe stimulation disrupts both formation and retrieval of recent memories. Brain and Cognition, 4(3), 287–295. 10.1016/0278-2626(85)90022-3. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4027062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen N, Chaieb L, Derner M, Hampel KG, Elger CE, Surges R, et al. (2018). Memory encoding-related anterior hippocampal potentials are modulated by deep brain stimulation of the entorhinal area. Hippocampus, 28(1), 12–17. 10.1002/hipo.22808. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29034573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, & Liu Z (2008). Multimodal functional neuroimaging:Integrating functional MRI and EEG/MEG. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering, 1, 23–40. 10.1109/rbme.2008.2008233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermiller MS, Chen YF, Parrish TB, & Voss JL (2020). Evidence for immediate enhancement of hippocampal memory encoding by network targeted theta-burst stimulation during concurrent FMRI. The Journal of Neuroscience, 40(37), 7155–7168. 10.1523/jneurosci.0486-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermiller MS, VanHaerents S, Raij T, & Voss JL (2018). Frequency-specific noninvasive modulation of memory retrieval and its relationship with hippocampal network connectivity. Hippocampus. 10.1002/hipo.23054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JB, Uncapher MR, & Wagner AD (2009). Posterior parietal cortex and episodic retrieval: Convergent and divergent effects of attention and memory. Learning & Memory, 16(6), 343–356. 10.1101/lm.919109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonowski J, & Rose M (2022). The functional dissociation of posterior parietal regions during multimodal memory formation. Human Brain Mapping, 43(11), 3469–3485. 10.1002/hbm.25861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Miller J, Lee SA, Coffey T, Watrous AJ, Sperling MR, et al. (2016). Direct electrical stimulation of the human entorhinal region and hippocampus impairs memory. Neuron, 92(5), 983–990. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.062. URL <GotoISI>://WOS:000391264200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobs M, Lee DJ, & Lozano AM (2020). Modifying the progression of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease with deep brain stimulation. Neuropharmacology, 171, Article 107860. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EL, Kam JWY, Tzovara A, & Knight RT (2020). Insights into human cognition from intracranial EEG: A review of audition, memory, internal cognition, and causality. Journal of Neural Engineering, 17(5), Article 051001. 10.1088/1741-2552/abb7a5. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32916678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun S, Lee SA, Kim JS, Jeong W, & Chung CK (2020). Task-dependent effects of intracranial hippocampal stimulation on human memory and hippocampal theta power. Brain Stimulation, 13(3), 603–613. 10.1016/j.brs.2020.01.013. URL <GotoISI>://WOS:000533522600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ (2023). Word pools. URL https://memory.psych.upenn.edu/Word_Pools.

- Kessels RP, de Haan EH, Kappelle L, & Postma A (2001). Varieties of human spatial memory: A meta-analysis on the effects of hippocampal lesions. Brain Research Reviews, 35(3), 295–303. 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00058-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DR, de Chastelaine M, Elward RL, Wang TH, & Rugg MD (2015). Recollection-related increases in functional connectivity predict individual differences in memory accuracy. The Journal of Neuroscience, 35(4), 1763–1772. 10.1523/jneurosci.3219-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y, & Amaral DG (2007). Macaque monkey retrosplenial cortex: Iii. cortical efferents. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 502(5), 810–833. 10.1002/cne.21346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciessa JQ, Grandy TH, Garrett DD, & Werkle-Bergner M (2020). Single-trial characterization of neural rhythms: Potential and challenges. NeuroImage, 206, Article 116331. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota S, Rugg MD, & Lega BC (2020). Hippocampal theta oscillations support successful associative memory formation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 40(49), 9507–9518. 10.1523/jneurosci.0767-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz ME, Valentin A, Seoane JJ, Morris RG, Selway RP, & Alarcon G (2010). Single pulse electrical stimulation of the hippocampus is sufficient to impair human episodic memory. Neuroscience, 170(2), 623–632. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.042. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20643192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxton AW, Tang-Wai DF, McAndrews MP, Zumsteg D, Wennberg R, Keren R, et al. (2010). A phase i trial of deep brain stimulation of memory circuits in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Neurology, 68(4), 521–534. 10.1002/ana.22089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DJ, Lozano CS, Dallapiazza RF, & Lozano AM (2019). Current and future directions of deep brain stimulation for neurological and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Neurosurgery, 131(2), 333–342. 10.3171/2019.4.jns181761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lega B, Burke J, Jacobs J, & Kahana MJ (2016). Slow-theta-to-gamma phase-amplitude coupling in human hippocampus supports the formation of new episodic memories. Cerebral Cortex, 26(1), 268–278. 10.1093/cercor/bhu232. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25316340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lega B, Germi J, & Rugg MD (2017). Modulation of oscillatory power and connectivity in the human posterior cingulate cortex supports the encoding and retrieval of episodic memories. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29(8), 1415–1432. 10.1162/jocn_a_01133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lega BC, Jacobs J, & Kahana M (2012). Human hippocampal theta oscillations and the formation of episodic memories. Hippocampus, 22(4), 748–761. 10.1002/hipo.20937. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21538660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leoutsakos J-MS, Yan H, Anderson WS, Asaad WF, Baltuch G, Burke A, et al. (2018). Deep brain stimulation targeting the fornix for mild alzheimer dementia (the advance trial): A two-year follow-up including results of delayed activation. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 64(2), 597–606. 10.3233/jad-180121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JJ, Rugg MD, Das S, Stein J, Rizzuto DS, Kahana MJ, et al. (2017). Theta band power increases in the posterior hippocampus predict successful episodic memory encoding in humans. Hippocampus, 27(10), 1040–1053. 10.1002/hipo.22751. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28608960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano AM, Fosdick L, Chakravarty MM, Leoutsakos J-M, Munro C, Oh E, et al. (2016). A phase ii study of fornix deep brain stimulation in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 54(2), 777–787. 10.3233/jad-160017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie SM, Kragel JE, Schuele SU, & Voss JL (2022). Human hippocampal responses to network intracranial stimulation vary with theta phase. eLife, 11. 10.7554/elife.78395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks. (2021). Statistics and machine learning toolbox user’s guide. MathWorks. URL https://www.mathworks.com/help/stats/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Merkow MB, Burke JF, Ramayya AG, Sharan AD, Sperling MR, & Kahana MJ (2017). Stimulation of the human medial temporal lobe between learning and recall selectively enhances forgetting. Brain Stimulation, 10(3), 645–650. 10.1016/j.brs.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Watrous AJ, Tsitsiklis M, Lee SA, Sheth SA, Schevon CA, et al. (2018). Lateralized hippocampal oscillations underlie distinct aspects of human spatial memory and navigation. Nature Communications, 9(1), 2423. 10.1038/s41467-018-04847-9. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29930307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miniussi C, Harris JA, & Ruzzoli M (2013). Modelling non-invasive brain stimulation in cognitive neuroscience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1702–1712. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan UR, Watrous AJ, Miller JF, Lega BC, Sperling MR, Worrell GA, et al. (2020). The effects of direct brain stimulation in humans depend on frequency, amplitude, and white-matter proximity. Brain Stimulation, 13(5), 1183–1195. 10.1016/j.brs.2020.05.009. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32446925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natu VS, Lin J-J, Burks A, Arora A, Rugg MD, & Lega B (2019). Stimulation of the posterior cingulate cortex impairs episodic memory encoding. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(36), 7173–7182. 10.1523/jneurosci.0698-19.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilakantan AS, Bridge DJ, Gagnon EP, VanHaerents SA, & Voss JL (2017). Stimulation of the posterior cortical-hippocampal network enhances precision of memory recollection. Current Biology, 27(3), 465–470. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.042. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28111154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez A, & Buno W (2021). The theta rhythm of the hippocampus: From neuronal and circuit mechanisms to behavior. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 15, Article 649262. 10.3389/fncel.2021.649262. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33746716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten LJ, & Rugg MD (2001). When more means less. Current Biology, 11(19), 1528–1530. 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00454-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastötter B, & Bäuml K-HT (2014). Distinct slow and fast cortical theta dynamics in episodic memory retrieval. NeuroImage, 94, 155–161. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps CJ, Murman DL, & Warren DE (2021). Stimulating memory: Reviewing interventions using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to enhance or restore memory abilities. Brain Sciences, 11(10), 1283. 10.3390/brainsci11101283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S, Sedillo JI, Brown KA, Ferrentino B, & Pesaran B (2020). A causal network analysis of neuromodulation in the mood processing network. Neuron, 107(5). 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei V, Thut G, & Silvanto J (2016). Information-based approaches of noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation. Trends in Neurosciences, 39(11), 782–795. 10.1016/j.tins.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, & Brett M (2000). Stereotaxic display of brain lesions. Behavioural Neurology, 12(4), 191–200. 10.1155/2000/421719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, & Rossini PM (2004). Tms in cognitive plasticity and the potential for rehabilitation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(6), 273–279. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML (2012). The angular gyrus. The Neuroscientist: a Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry, 19(1), 43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghier ML (2022). Multiple functions of the angular gyrus at high temporal resolution. Brain Structure & Function, 228(1), 7–46. 10.1007/s00429-022-02512-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestieri C, Shulman GL, & Corbetta M (2017). The contribution of the human posterior parietal cortex to episodic memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(3), 183–192. 10.1038/nrn.2017.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour RA, Alexander N, & Maguire EA (2022). Robust estimation of 1/f activity improves oscillatory burst detection. European Journal of Neuroscience, 56(10), 5836–5852. 10.1111/ejn.15829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvanto J, Muggleton N, & Walsh V (2008). State-dependency in brain stimulation studies of perception and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(12), 447–454. 10.1016/j.tics.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Peers PV, Mazuz YS, Berryhill ME, & Olson IR (2010). Dissociation between memory accuracy and memory confidence following bilateral parietal lesions. Cerebral Cortex, 20(2), 479–485. 10.1093/cercor/bhp116. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19542474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, et al. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage, 23. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon EA, Kragel JE, Gross R, Lega B, Sperling MR, Worrell G, et al. (2018). Medial temporal lobe functional connectivity predicts stimulation-induced theta power. Nature Communications, 9(1). 10.1038/s41467-018-06876-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers HJ (2001). Unilateral temporal lobectomy patients show lateralized topographical and episodic memory deficits in a virtual town. Brain: a Journal of Neurology, 124(12), 2476–2489. 10.1093/brain/124.12.2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthana N, Haneef Z, Stern J, Mukamel R, Behnke E, Knowlton B, et al. (2012). Memory enhancement and deep-brain stimulation of the entorhinal area. The New England Journal of Medicine, 366(6), 502–510. 10.1056/NEJMoa1107212. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22316444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Nagy AJ, Barcsai L, Li Q, Ohsawa M, Mizuseki K, et al. (2021). The medial septum as a potential target for treating brain disorders associated with oscillopathies. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 15, Article 701080. 10.3389/fncir.2021.701080. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34305537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakral PP, Wang TH, & Rugg MD (2017). Decoding the content of recollection within the core recollection network and beyond. Cortex; a Journal Devoted To the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior, 91, 101–113. 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibon R, Fuhrmann D, Levy DA, Simons JS, & Henson RN (2019). Multimodal integration and vividness in the angular gyrus during episodic encoding and retrieval. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(22), 4365–4374. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2102-18.2018. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30902869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titiz AS, Hill MRH, Mankin EA, Aghajan ZM, Eliashiv D, Tchemodanov N, et al. (2017). Theta-burst microstimulation in the human entorhinal area improves memory specificity. eLife, 6. 10.7554/eLife.29515.001. URL <GotoISI>://WOS:000413724900001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini P, O’Brien J, O’Keefe K, Pihlajamaki M, Laviolette P, & Sperling RA (2011). What goes down must come up: Role of the posteromedial cortices in encoding and retrieval. Cerebral Cortex, 21(1), 22–34. 10.1093/cercor/bhq051. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20363808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Poldrack RA, Eldridge LL, Desmond JE, Glover GH, & Gabrieli JDE (1998). Material-specific lateralization of prefrontal activation during episodic encoding and retrieval. NeuroReport, 9(16), 3711–3717. 10.1097/00001756-199811160-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JX, Rogers LM, Gross EZ, Ryals AJ, Dokucu ME, Brandstatt KL, et al. (2014). Targeted enhancement of cortical-hippocampal brain networks and associative memory. Science, 345(6200), 1054–1057. 10.1126/science.1252900. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25170153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigenand A, Mölle M, Werner F, Martinetz T, & Marshall L (2016). Timing matters: Open-loop stimulation does not improve overnight consolidation of word pairs in humans. European Journal of Neuroscience, 44(6), 2357–2368. 10.1111/ejn.13334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten TA, Hughes AM, Dickson CT, & Caplan JB (2011). A better oscillation detection method robustly extracts EEG rhythms across brain state changes: The human alpha rhythm as a test case. NeuroImage, 54(2), 860–874. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazar Y, Bergstrom ZM, & Simons JS (2017). Reduced multimodal integration of memory features following continuous theta burst stimulation of angular gyrus. Brain Stimulation, 10(3), 624–629. 10.1016/j.brs.2017.02.011. URL https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28283370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh N, & Rose NS (2019). How can transcranial magnetic stimulation be used to modulate episodic memory? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.