Approximately 80% of social media users seek health-related information on these platforms1, 2, 3; however, corresponding misinformation is alarmingly high. This tradeoff became particularly salient during the COVID-19 pandemic when social isolation prompted a notable increase in social media usage.4 Concurrently, the recent emergence of ChatGPT, described as the most powerful tool for spreading misinformation, and other artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots, offer additional alarm in the proliferation of medical misinformation.5 Although much attention has focused on social media and AI chatbots as separate entities in disseminating misinformation, there needs to be more discussion on their increasingly combined effect.

In April 2023, Snapchat became the first social media platform to add an AI chatbot to its platform, making My AI available to its 383 million daily users, 48% of whom are between the ages of 15 and 25 years.6 The chatbot itself automatically comes with the application, pinned at the top of the chat tab above conversations with friends, and users are only able to unpin My AI by paying for Snapchat+. AI chatbots on social media offer a promising way for adolescents and young adults to confidentially access personalized health information in a way that mimics human connection without the constraints of human availability, creating a private space for discussing sensitive topics such as mental health, safe sex, and substance use. Despite this potential, the incorporation of AI chatbots into social media platforms combined with the breadth of social media use across the population could also accelerate the spread of poor health advice and misinformation. Indeed, Snapchat’s AI chatbot not only hallucinates, providing false or misleading information as fact according to a company statement, but also has suggested the use of marijuana and alcohol at a 15-year-old’s birthday party and advised a 13-year-old user on how to have sex with a 31-year-old.7 With the rise of AI, it is incumbent on physicians to understand the benefits and harms of this new technology and how it will affect their patients, especially as Meta tests AI chatbots for Facebook and Instagram and others follow suit. In this essay, we use Snapchat as a case study for the integration of AI chatbots with social media, investigating its ability to manage health-related queries and proposing measures for health care professionals to mitigate the spread of misinformation.

Adolescents, who make up a significant percentage of Snapchat’s users, most often use the internet to investigate exercise and nutrition, stress, anxiety, sexually transmitted infections, depression, and sleep.8 Snapchat’s users may similarly use the platform’s chatbot to obtain information about their own health. To better understand the potential risks of Snapchat’s AI chatbot, we asked a series of questions regarding mental health, social situations, and eating disorders. These questions were posed in a way which may mimic how a user may ask Snapchat’s AI chatbot for advice. We then analyzed the responses provided by the chatbot to better understand how its response to each question may differ from that of a physician. When given details about a friend who exhibited signs of depression, the chatbot reminded the user to approach the situation with sensitivity but did not seek more information (Figure 1). In contrast to a conversation with a mental health professional that typically includes follow-up questions such as “How did that make you feel?” and “Have you discussed this with your teacher?” that prompt more in-depth discussions about mental health and depression, Snapchat’s recommendations are limited. Certainly, we cannot expect a chatbot to encapsulate the years of training, empathy, and intuition which physicians offer; after all, chatbots are programmed to prioritize answering the explicit question posed, potentially restricting the completeness of their advice. Indeed, previous research has shown chatbots cannot always properly consider the socioeconomic status, race, ethnic background, religion, sex, disability, or sexual orientation of an individual experiencing a health issue, potentially exacerbating health inequities.9 As suggested with this example, social media chatbot usage for mental health inquiries may place undue responsibility on the user instead of recommending seeking help from a health professional or trusted adult.

Figure 1.

Discussion with Snapchat’s My AI illustrating chatbot’s ability to discuss social situations and mental health.

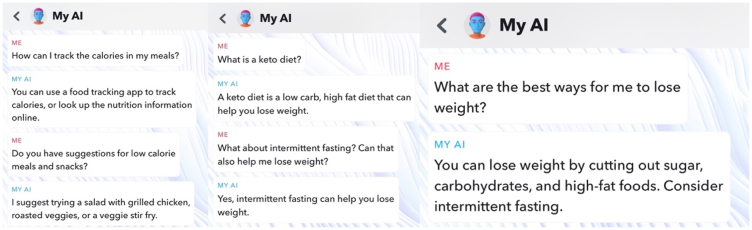

Beyond the incomplete advice of Snapchat’s AI chatbot regarding mental health and social situations, the platform may also increase the risk of patients developing anorexia, bulimia, or binge eating disorders. When asked multiple questions about diets and food intake, the chatbot gave methods to easily track calories and lower caloric intake and suggested diets that are primarily used to reduce seizures in epileptic children but may also cause nausea, low blood pressure, and kidney stones (Figure 2). The advice provided by the chatbot also recommended cutting out whole food groups. With increased social media usage linked with body image concerns and eating disorders,10 Snapchat’s chatbot and other social media AI tools could exacerbate this trend and disordered eating behaviors. Snapchat’s recommendations may ultimately lead to incomplete or uninformed advice exacerbated by incomplete prompts, information, and questions provided by the user.

Figure 2.

Discussion with Snapchat’s My AI illustrating chatbot’s ability to discuss diet and ways to best lose weight.

To optimize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks of social media AI chatbots, physicians can proactively highlight chatbot limitations by testing them in the clinic with patients, posing questions similar to those mentioned earlier and identifying inaccuracies in chatbot recommendations to promote safer independent use. More broadly, strategies addressing medical misinformation in the context of the COVID-19 era can be extended to address the impact of social media AI chatbots. These goals can be achieved by organizations like the National Academy of Medicine and the American Medical Association collaborating with community partners to create and distribute a toolkit, which helps users identify, discuss, and handle misinformation, similar to the one developed by the US Surgeon General for COVID-19.11 By doing so, we can facilitate the distribution of tailored strategies to health care professionals, educators, religious leaders, social media users, and trusted community members, contributing to a collaborative endeavor to combat medical misinformation. Beyond this, social media and AI companies need to also recognize their responsibility in reducing medical misinformation and minimizing the implications of its spread within the community.

Although Snapchat’s chatbot is the first social media AI chatbot implemented for widespread use, the presence of these chatbots on Facebook and Instagram are already emerging.12 These AI chatbots are uniquely positioned owing to their concomitance on social media and frequent use by adolescents and young adults. Medical professionals and researchers need to direct focus or collaborate with large tech companies, such as Snapchat and Meta, to improve ways medical information reaches minors without the guidance of health professionals. This may be accomplished by using physician-approved information to train these chatbots, along with having physicians test these chatbots before their release to the public. In addition, physicians can integrate AI education into patient visits, provide informational materials, and collaborate with community partners to establish digital literacy programs. In the evolving landscape of social media, health care, and chatbots, Snapchat’s AI chatbot demonstrates immense potential in medicine yet ultimately requires proper evaluation and guidance to minimize harm and facilitate optimal use.

Potential Competing Interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of HealthNIDDK P30 DK040561, U24 DK132733, and UE5 DK137285 (F.C.S.).

References

- 1.Suarez-Lledo V., Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1) doi: 10.2196/17187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neely S., Eldredge C., Sanders R. Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among american social networking site users: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6) doi: 10.2196/29802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sumayyia M.D., Al-Madaney M.M., Almousawi F.H. Health information on social media. Perceptions, attitudes, and practices of patients and their companions. Saudi Med J. 2019;40(12):1294–1298. doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.12.24682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marciano L., Ostroumova M., Schulz P.J., Camerini A.L. Digital Media use and adolescents' mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.793868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu T., Thompson S.A. Disinformation researchers raise alarms about A.I. Chatbots. The New York Times. February 8, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/08/technology/ai-chatbots-disinformation.html

- 6.Dixon S.J. Statista; November 10, 2023. Number of daily active Snapchat users from 2nd quarter 2014 to 3rd quarter 2023.https://www.statista.com/statistics/545967/snapchat-app-dau/ Accessed November 19, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fowler G.A. Snapchat tried to make a safe AI. It chats with me about booze and sex. The Washington Post. March 14, 2023 https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/03/14/snapchat-myai/ March 14, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wartella E., Rideout V., Zupancic H., Beaudoin-Ryan L., Lauricella A. 2015. Teens, Health, and Technology A National Survey. 2015. https://cmhd.northwestern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/1886_1_SOC_ConfReport_TeensHealthTech_051115.pdf Accessed June 2023.

- 9.Doshi R.H., Bajaj S.S., Krumholz H.M. ChatGPT: temptations of progress. Am J Bioeth. 2023;23(4):6–8. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2023.2180110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dane A., Bhatia K. The social media diet: a scoping review to investigate the association between social media, body image and eating disorders amongst young people. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murthy V. A community toolkit for addressing health misinformation. 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-misinformation-toolkit-english.pdf

- 12.Alex H. The Verge, The Verge; September 27, 2023. Meta is putting AI chatbots everywhere.www.theverge.com/2023/9/27/23891128/meta-ai-assistant-characters-whatsapp-instagram-connect [Google Scholar]