Abstract

Introduction:

Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT) aids the physicians in early management of concussion among suspected athletes and its 6th version was published in 2023 in English. This study aimed to describe the translation and validation process of SCAT6 from English to Persian.

Methods:

The Persian translation of SCAT6 and its evaluation has been done in seven stages: initial translation, appraisal of the initial translation, back translation, appraisal of the back-translation, validation (face and content validities), final reconciliation and testing by simulation.

Results:

Initial translation, was done by two bilingual translators followed by an initial appraisal, which was made by both translators and one general physician. Back translation was done by two naïve translators who were unfamiliar with SCAT6, followed by its appraisal by initial translators. Face and content validity of the translation were surveyed by medical professionals and athletes and the results of the validation process were provided to the reconciliation committee and this committee made the modifications needed. Finally, the use of Persian SCAT6 was simulated and the mean time needed to complete the Persian SCAT6 was roughly a little more than 10 minutes.

Conclusions:

The present study provides the readers with the translation and cross-cultural adaptation process of SCAT6 from English to Persian. This translated version will be distributed among the Iranian sports community for assessing concussions among athletes.

Key Words: Brain concussion, Athletic injuries, Neurologic examination, Validation study

1.Introduction:

Concussion is a syndrome consisting of transient and immediate brain dysfunction, which is caused by direct or indirect trauma to the brain and is considered a medical emergency (1). In most cases, concussion is associated with a wide range of somatic, cognitive, and psychological signs and symptoms with headache being the most common symptom. In 10%-15% of patients, these signs and symptoms may persist and deteriorate the quality of life among sufferers (2). It has been shown that early diagnosis of concussion and treatment of its subsequent complications is associated with better outcomes and earlier recovery (3). Concussion is prevalent among athletes and is much more common in certain sports such as rugby, martial arts, soccer, etc. Therefore, it is vital for sports physicians to make an early diagnosis of concussion among athletes, managing its emergent effects, enhancing recovery, and preventing possible recurrent injuries, since repetitive episodes of concussion may cause persistent symptoms or permanent brain injury (3, 4).

Considering the aforementioned importance of early diagnosis and management of concussion, several assessment tools have been proposed for this purpose. The most used tools are the Standard Assessment of Concussion (SAC), Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT) and Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing (ImPACT) (5).

One of the widely used tools for assessing concussion among athletes is SCAT. The main application of SCAT is to provide a standardized method for evaluating athletes for concussion and managing their return to play. It is designed for use by healthcare professionals to assess symptoms, physical signs, balance, behavior, cognition, and sleep disturbance in athletes suspected of having sustained a concussion. The tool helps in making informed decisions about an athlete's safety and health regarding returning to sports after a concussion incident. SCAT is generally composed of multiple sections consisting of evaluation of observable signs and symptoms and specific physical, mental, and cognitive assessments and red flags for the early management of concussion in athletes aged 13 years and older. From its first version, which was developed during the second International Conference on Concussions in Sport in 2004 to its latest version (SCAT6), which was developed in 2023, this tool has undergone several changes and updates (5-8).

SCAT6 introduces several key updates from SCAT5, aiming to better accommodate the clinical realities faced by healthcare professionals and improve the assessment's effectiveness. These changes include a more detailed athlete demographic section, a revised "recognise and remove" section, enhancements to the immediate assessment and neurological screening, a new coordination and ocular/motor screen, and a revised “Red Flags” section. Specifically, SCAT6 extends the application window to within 72 hours up to 7 days post-injury, emphasizes a more thorough evaluation process lasting 10-15 minutes, and underscores the importance of serial evaluations to track symptomatology over time (9, 10).

While specific studies directly assessing the reliability and validity of SCAT6 are sparse, the development of SCAT6 incorporated extensive feedback from clinical experience, empirical data, and systematic reviews aimed at enhancing its clinical utility. In a systematic review assessing the acute evaluation of sport-related concussion, SCAT has been identified to effectively discriminate between concussed and non-concussed athletes within 72 hours of injury, with diminishing utility up to 7 days post-injury. This underscores the tool's role in early concussion management, while highlighting areas for future enhancements (11).

After the publication of the 6th version of SCAT, the department of sports and exercise medicine of Tehran University of Medical Sciences decided to translate the English version of this tool to Persian and evaluate the translated version in order to make it available among the Iranian sports community. To the date of preparing this article, no systematic translation and cross-cultural adaptation of SCAT 6 to any language has been published.

The goal of this article is to describe the process of translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Persian version of SCAT6.

2.Methods:

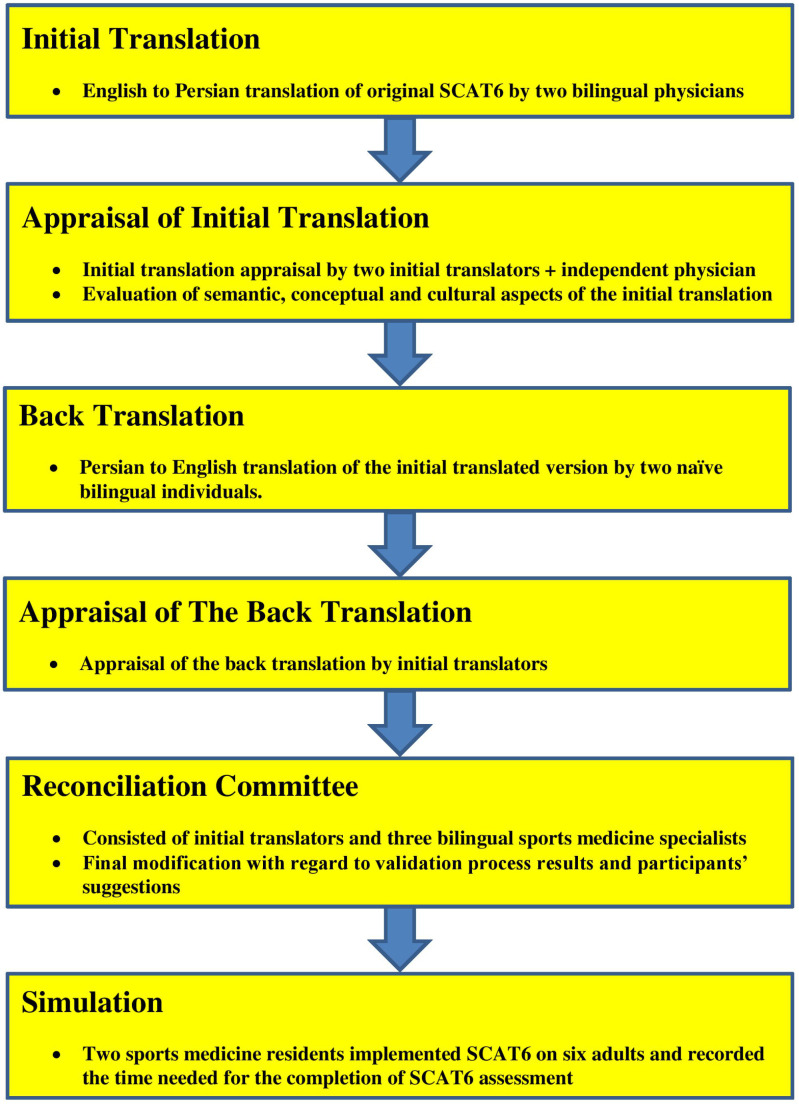

The method of Persian translation of SCAT6 is inspired by two preceding translations of SCAT, the Chinese translation of SCAT3 (12) and the Arabic translation of SCAT5 (13). SCAT6 comprises two types of assessments, first being objective evaluations, which is done by healthcare providers and second, the subjective evaluations, which are accomplished by responses from athletes, and require the athletes to completely understand the concepts and sentences. Although the translation process of these two parts is generally the same, the evaluation of translations of each part was made by their corresponding target population. The Persian translation and cross-cultural adaptation of SCAT6 followed by psychometric evaluations, has been done in seven stages: initial translation, appraisal of the initial translation, back translation, appraisal of the back-translation, validation, final reconciliation, and testing by simulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Steps of Persian Translation and Cross-cultural Adaption of Sport Concussion Assessment Tool version 6 (SCAT6).

2.1 Initial translation

With regards to cross-cultural considerations, the initial translation of SCAT6 was independently performed by two bilingual physicians with Persian being their native language. One of the translators was a certified sports medicine specialist and the other one was a general practitioner working in the field of sports medicine.

2.2Appraisal of the initial translation

After each individual translator made their translated version separately, both of them and one general physician held a meeting with the goal of producing the initial Persian translation of SCAT6. The group discussed their opinion about semantic, conceptual, and cultural aspects of the translation and agreed on a single version of the initial translation, which they thought to be the most comprehensible for both athletes and healthcare providers.

2.3Back translation

Two SCAT6 naïve individuals (one bilingual general physician and one bilingual non-physician) back-translated the primary Persian version of SCAT6 to English.

2.4Appraisal of the back-translation

The two mentioned individuals in the previous section sent their English version to the initial translators and following that, the initial translators held a meeting and compared the original version with the back-translated version; and the results seemed satisfactory to both translators, although with minor modifications. Thus, they agreed on a primary Persian translation of SCAT6.

2.5Validation

The words and sentences of the translated version were split into two separate questionnaire forms, the athlete version consisted of items directly related to athletes, which were surveyed by 20 athletes, and the healthcare provider version consisted of items related to healthcare providers, which was surveyed by 20 individuals related to healthcare. The number of these evaluators was larger than previous versions of SCAT translations with the Chinese translation of SCAT3 using 18 physiotherapists and 11 athletes and Arabic SCAT5 using only 5 healthcare providers.

In each version, every sentence, word, or item was surveyed by a 5-point Likert scale regarding the apparent quality of translation (face validity). Any translated item with a mean score above 3.5 was approved for the final version and translated items with a mean score below or equal to 3.5 were referred to the final reconciliation committee for possible modifications.

Also, the ability of translated words or sentences or items to transmit the desired concept (content validity), was evaluated (three options for each item consisting of “essential”, “useful, but not necessary” or “not necessary”). The evaluation results were reported as content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). The CVR of each item was compared with “Lawshe’s critical value for CVR” and if the calculated CVR was below the critical value, the item was referred to the reconciliation committee.

At the end of each version of questionnaires, the respondents were asked to express their opinions about each of the translated items, if any.

2.6Final reconciliation

Before testing, the translated version along with the scores, CVR and CVI of translated items and respondents’ written suggestions and opinions were given to the reconciliation committee. This committee consisted of initial translators and 3 bilingual sports medicine specialists.

2.7Testing by simulation

The proposed Persian translation of SCAT6 was tested by two sports medicine residents who were familiar with SCAT6. Each resident simulated the implementation of SCAT6 on three healthy adults from both genders and recorded the time needed for the completion of SCAT6 assessments. They also looked for possible flaws in the completion process of the Persian version of SCAT6.

3.Results:

After the initial translation and back translation and their respective appraisals the validation process began as mentioned in the methods section.

The athlete version of the validity survey consisted of 42 items and was given to 20 amateur and professional volleyball, football, judo, karate, taekwondo, and wrestling athletes from both genders. Regarding the face validity, the scores of 41 out of 42 items were above 3.5 and only the translation of one item (feeling like “in a fog”) scored 3.35. Assessment of content validity showed that the CVR of every item was above the critical value (Table 1).

Table 1.

Report of content validity evaluation of Persian translation of SCAT6

| Items related to | Number of Assessors | Lawshe’s Critical Value | CVR | CVI |

| Healthcare Provider | 20 | 0.42 | 0.76 – 0.98 | 0.88 |

| Athlete | 20 | 0.42 | 0.52 – 0.95 | 0.69 |

CVR = Content Validity Ratio, CVI = Content Validity Index. CVR reported as (minimum – maximum). SCAT6: Sport Concussion Assessment Tool version 6.

The healthcare provider version of the validity survey consisted of 62 items and was given to 20 general physicians and sports medicine specialists. The score of all items in face validity evaluation was above 4 and CVR for all the items were above the critical value (Table 1).

With regards to the initial validity survey results, the reconciliation committee decided to modify the single item with a face validity score of less than 3.5 and the suggestions and comments of survey respondents were implemented.

The Persian SCAT6 was simulated on six healthy adults with a mean age of 37 years old and the time needed to complete each assessment of SCAT6 was recorded. The mean time to complete the Persian SCAT6 for these individuals was a little more than 10 minutes (Table 2). It has been mentioned in the original version of SCAT6 that “The SCAT6 cannot be performed correctly in less than 10-15 minutes”. No significant flaws were recorded during the process.

Table 2.

Results of Persian SCAT6 simulation on six healthy individuals

| Case | Gender | Time* |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 11:30 |

| 2 | Male | 10:45 |

| 3 | Male | 10:55 |

| 4 | Male | 12:00 |

| 5 | Female | 10:15 |

| 6 | Female | 8:30 |

| Mean | 10:39 |

*: time to complete the survey (it is presented as mm:ss). SCAT6: Sport Concussion Assessment Tool version 6.

4.Discussion:

In response to emerging needs for precise concussion assessment, SCAT6 has been refined to encompass a broader range of cognitive, balance, and coordination evaluations, aimed at providing a comprehensive tool for healthcare professionals. This version's adaptability and detailed components facilitate a nuanced approach to concussion management, reinforcing the tool's significance in promoting athlete health and safety.

To date, this is the only systemic Persian translation of SCAT6 that will be distributed among the Iranian sports community for assessing concussion. A lack of an education program about concussion in sports and a standard concussion tool was observed among team physicians in Iran. So, the sports and exercise medicine department of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, as the pioneer of sports medicine in Iran, decided to solve these critical problems.

The first step toward solving these problems was to find a standard assessment tool for concussion, and we found SCAT as a widely accepted assessment tool for concussion, used in sports events worldwide. The next step was to translate this tool to Persian in order to publish and distribute it among the Iranian sport community.

Before starting the translation process, we reviewed the works of other groups on the translation of SCAT. We found the Chinese translation of SCAT3 and the Arabic translation of SCAT5 (12, 13) and our translation process was inspired by these two previously published translations, although we had some critiques about these works. Our main critique was that the teams who translated SCAT to Chinese and Arabic, had the “questionnaire translation approach” toward SCAT, which we think is not an appropriate approach because SCAT is a tool and not a questionnaire. For example, the Chinese translation reported an inter-rater reliability based on evaluations of healthy individuals, which is not a correct way to assess the inter-rater reliability, since the assessment results of a healthy person using SCAT will almost always be the same, regardless of the assessor. Another example of a possible error in the Chinese version would be the report of test-retest reliability, which, similar to inter-rater reliability, was calculated using SCAT on healthy individuals. However, the results of SCAT in healthy individuals are obviously the same every time and can’t be used for calculating test-retest reliability. Needless to say, assessing test-retest reliability on concussed individuals, is not an option either, since the mental and physical status of a concussed person is not the same at two different timeframes.

The strength of our study was that by assessing the methods and after considering the possible flaws in the two previously translated versions of SCAT, we concluded our own unique approach toward translating SCAT6 to Persian, which can be a good model for translation of SCAT and other similar tools in the future.

4.1Limitations

One of the limitations of our project can be the limited number of individuals for assessing validity of the Persian version. The other mentionable limitation is that we haven’t provided the athletes and physicians who assessed the validity of our translated version, the original English version to compare it with the Persian translations.

Translating the future versions of SCAT to Persian along with increasing the knowledge of sports physicians about concussion in sports and the usage of SCAT will be one of our priorities in the future.

5.Conclusion:

The present study provides the readers with the translation process of SCAT6 from English to Persian. To our knowledge, this is the only systemic Persian translation of SCAT6 that will be distributed among the Iranian sports community for assessing concussion among athletes along with educating sports physicians about concussion in sports and the usage of SCAT6 in athletic settings.

6.Declarations:

6.1Acknowledgment

We want to thank the staff of the sports and exercise medicine department of Tehran University of Medical Sciences for facilitating this project and also, we want to thank the athletes who cooperated to help us with our work.

6.2Authors’ Contribution

FH: Proposing the study design, drafting the manuscript, final revision MMT: Proposing the study design, drafting the manuscript, data collection, statistical analysis, RKH: Data collection, MJ: Final revision.

All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

6.3Ethical approval

Deployment of ethical guidelines are not applicable regarding this study.

6.4Competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

6.5Funding

The authors of this paper declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding this article.

6.6Using artificial intelligence chatbots

No artificial intelligence chatbots were used for preparation of this article.

References

- 1.American Association of Neurosurgical Surgeons. Concussion 2022 . [Available from: https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Concussion.

- 2.Skjeldal OH, Skandsen T, Kinge E, Glott T, Solbakk AK. Long-term post-concussion symptoms. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2022;142(12):e713. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.21.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kontos AP, Jorgensen-Wagers K, Trbovich AM, Ernst N, Emami K, Gillie B, et al. Association of time since injury to the first clinic visit with recovery following concussion. JAMA neurol. 2020;77(4):435–40. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piedade SR, Hutchinson MR, Ferreira DM, Cristante AF, Maffulli N. The management of concussion in sport is not standardized A systematic review. J Safety Res. 2021;76:262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman MW, Su CA, Trivedi NN, Lee MK, Nelson GB, Cupp SA, et al. The Current Status of Concussion Assessment Scales: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2021;9(6):e20. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echemendia RJ, Meeuwisse W, McCrory P, Davis GA, Putukian M, Leddy J, et al. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition (SCAT5): Background and rationale. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):848–50. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider KJ, Patricios J, Echemendia RJ, Makdissi M, Davis GA, Ahmed OH, et al. Concussion in sport: the consensus process continues. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(19):1059–60. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yengo-Kahn AM, Hale AT, Zalneraitis BH, Zuckerman SL, Sills AK, Solomon GS. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;40(4) doi: 10.3171/2016.1.FOCUS15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Echemendia RJ, Brett BL, Broglio S, Davis GA, Giza CC, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Introducing the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 6 (SCAT6) Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(11):619–21. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2023-106849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sport Med School. SCAT 6 – 2023 Concussion Update 2023. [Available from: http://sportmedschool.com/scat-6-2023-concussion-update /

- 11.Echemendia RJ, Burma JS, Bruce JM, Davis GA, Giza CC, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Acute evaluation of sport-related concussion and implications for the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT6) for adults, adolescents and children: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57(11):722–35. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeung EW, Sin YW, Lui SR, Tsang TWT, Ng KW, Ma PK, et al. Chinese translation and validation of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 3 (SCAT3) BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000450. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holtzhausen LJ, Souissi S, Sayrafi OA, May A, Farooq A, Grant CC, et al. Arabic translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 (SCAT5) Biol Sport. 2021;38(1):129–44. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2020.97673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]