Domestic violence can be physical, sexual, or psychological. Physical and sexual violence by an intimate partner are common problems, affecting 20-50% of women at some stage in life in most populations surveyed globally.1 Between 3% and 50% of women have experienced it in the past year.1 Domestic violence has a profound impact on the physical and mental health of those who experience it. As well as injuries, it is associated with an increased risk of a range of physical and mental health problems and is an important cause of mortality from injuries and suicide.2

Review of international literature on risk of domestic violence shows that although it is greatest in relationships and communities where the use of violence in many situations is normative, notably when witnessed in childhood, it is substantially a product of gender inequality and the lesser status of women compared with men in society.3 Except for poverty, few social and demographic characteristics define risk groups. Poverty increases vulnerability through increasing relationship conflict, reducing women's economic and educational power, and reducing the ability of men to live in a manner that they regard as successful. Violence is used frequently to resolve a crisis of male identity. Domestic violence is often associated with heavy alcohol drinking.3 Research suggests that the different factors have an additive effect.

Although interventions that alter the prevalence of any of these risk factors may alter the prevalence of domestic violence, few programmes that seek primarily to reduce, for example, poverty or consumption of alcohol evaluate the impact on the prevalence of domestic violence. A notable exception was the Grameen Bank project in Bangladesh, where ethnographic evaluation suggested that women participating in the microcredit programme were protected to some extent against domestic violence by having a more public social role.4

Evidence suggests that domestic violence can be prevented in populations in developing countries that have not been specifically identified as affected through life skills type programmes that address gender issues and include relationship skills. A review of qualitative evaluations and experiences using the Stepping Stones,5 a training package to promote sexual and reproductive health in various communities in Africa and Asia, found a reduction in conflict and violence in sexual relationships to be a major impact in all communities studied.6

Most interventions on domestic violence focus on women and men who have been identified as abused or abusing. Evaluation of initiatives has been sorely lacking. The only review of programmes to prevent domestic violence found 34 projects that had been evaluated, two thirds of which were in the criminal justice system.7 In many countries interventions focus on legal redress and secondary prevention through protection orders, shelters, counselling services, specialised police units and courts, and mandatory arrest laws. Although many women find these helpful, evidence of their effectiveness in preventing domestic violence is limited.8 Treatment programmes for abusers are similarly found in many countries but, unless compulsory, they are plagued by very high drop out rates. Again the evidence for their effectiveness is weak.9

The two papers in this issue confirm previous research that shows that domestic violence is a common underlying problem in clinical practice (pp 271, 274).10,11 Bradley et al show strong associations with anxiety and depression.10 The papers also confirm research findings from the United States that show that most women welcome inquiries, but doctors and nurses rarely ask about it.10,11 One obvious explanation for this is that they are not trained to do so and are uncertain what they can do.12 Gender and health issues, including domestic violence, feature little in undergraduate and postgraduate medical training programmes and textbooks.

In many parts of the world training programmes on domestic violence for staff in service focus on training staff to ask direct questions about abuse, assess safety, provide a simple supportive message such as no woman deserves to be beaten, and provide information on legal rights and where to go for further support or counselling. However, the evidence that these activities benefit women is still limited. Research is hampered by the fact that many programmes have failed to achieve the desired change in clinical practice,12 although this is more likely to occur if programmes are supported by other changes in the working environment such as having inquiry protocols, posters reminding staff, or prompts in the case notes.13 Other key problems with training have been that programmes are too short (often one to three hours long), neglect the personal experiences of domestic violence of the staff that may influence their approach to the issue, fail to provide an adequate understanding of this complex behavioural problem, and fail to set it in a broader gender context. Advances in effectiveness of efforts to introduce routine inquiry into clinical practice are needed before large scale evaluation is possible.

Unfortunately the lack of evidence of effectiveness of interventions may pose a barrier to action,14 and Richardson et al argue that indeed it should be.11 However the question of what is effectiveness in this context has not been resolved and it is premature to suggest that lack of evidence equates to ineffectiveness. Bradley et al present an important argument that inquiry about domestic violence should be regarded as a way of “uncovering and reframing a hidden stigma” and that inquiry is in itself beneficial, even if no action immediately follows from it.10

The impact of domestic violence on health has been well established and the rationale for prioritising prevention, including addressing it in clinical practice, is strong. A need exists for much more research on screening outcomes, acceptability, effectiveness, and effective interventions in changing clinical practice. Fresh medical graduates need to be equipped with an understanding of gender issues in society, the impact of gender inequality on health, and of the dynamics of the problem of domestic violence so that they are better placed to respond to the issue, understand the possibilities and limitations of their role, and adjust their practice to emerging scientific evidence. Socioeconomic inequalities have become a mainstream part of medical teaching—it is now time for the medical establishment to embrace the issue of gender.

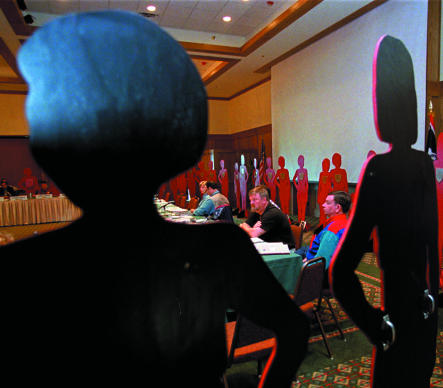

Figure.

AP PHOTO

Life size wood silhouettes representing women and children murdered as a result of domestic violence in Wyoming, USA since 1985.

References

- 1.Heise L, Ellsberg M, Gottemoeller M. Ending violence against women. Baltimore: Center for Communication Programs, John Hopkins School of Public Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell J. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jewkes R Intimate partner violence: causation and primary prevention. Lancet (in press).

- 4.Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Riley AP, Akhter S. Credit programmes, patriarchy and men's violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1729–1742. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welbourn A. Stepping stones. Oxford: Strategies for Hope; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon G, Welbourn A. Stepping stones and men. Washington,DC: InterAgency Gender Working Group; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalk R, King PA. Violence in families: assessing prevention and treatment programs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Justice and Association. Legal interventions in family violence: research findings and policy implications. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edleson JL. Intervention for men who batter: a review of research. In: Stith SR, Straus MA, editors. Understanding partner violence: prevalence, causes, consequences and solutions. Minneapolis: National Council on Family Relations; 1995. pp. 262–273. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley F, Smith M, Long J, O'Dowd T. Reported frequency of domestic violence: cross sectional survey of women attending general practice. BMJ. 2002;324:271–274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7332.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson J, Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Wai SC, Moorey S, Feder G. Identifying domestic violence: cross sectional study in primary care. BMJ. 2002;324:274–277. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7332.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsons LH, Moore ML. Family violence issues in obstetrics and gynaecology, primary care and nursing texts. Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;90:596–599. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13..Garcia-Moreno C. What is an appropriate health service response to intimate partner violence against women? Dilemmas and opportunities. Lancet (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Thompson RS, Rivara FP, Thompson DC, Barlow WE, Sugg NK, Rowland MD, et al. Identification and management of domestic violence. A randomised controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:252–262. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]