Abstract

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic condition predominantly affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints. This article provides an in-depth overview of the current approaches to diagnosing, monitoring, and managing axSpA, including insights into developing terminology and diagnostic difficulties. A substantial portion of the debate focuses on the challenging diagnostic procedure, noting the difficulty of detecting axSpA early, particularly before the appearance of radiologic structural changes. Despite normal laboratory parameters, more than half of axSpA patients experience symptoms. X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are essential for evaluating structural damage and inflammation. MRI can be beneficial when there is no visible structural damage on X-ray as it can help unravel bone marrow edema (BME) as a sign of ongoing inflammation. The management covers both non-pharmacological and pharmacological approaches. Lifestyle modifications, physical activity, and patient education are essential components of the management. Pharmacological therapy, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), are explored, emphasizing individualized treatment. To effectively manage axSpA, a comprehensive and well-coordinated approach is necessary, emphasizing the significance of a multidisciplinary team. Telehealth applications play a growing role in axSpA management, notably in reducing diagnostic delays and facilitating remote monitoring. In conclusion, this article underlines diagnostic complexities and emphasizes the changing strategy of axSpA treatment. The nuanced understanding offered here is designed to guide clinicians, researchers, and healthcare providers toward a more comprehensive approach to axSpA diagnosis and care.

Keywords: Axial spondyloarthritis, Spondylarthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Diagnosis, Disease management, Treatment, Telehealth

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a long-lasting condition, delineated into two discernible manifestations: axial SpA (axSpA), predominantly affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints, and peripheral SpA (pSpA), exerting its influence on the peripheral joints and related structures. The paramount manifestation of axSpA is radiographic axSpA (r-axSpA), synonymous with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), traditionally identified using the modified New York criteria [1]. The distinctive feature of r-axSpA is radiographic sacroiliitis. Nevertheless, the phrase is inaccurately coined as sacroiliitis, specifically described as the inflammation of the sacroiliac joint. Radiographs solely identify structural damage rather than inflammation [2, 3].

The main focus has been on the existing challenges in identifying and classifying patients with axial symptoms of SpA who do not meet the sacroiliitis criteria [4]. Patients without structural damage were first categorized as having early or preradiographic axSpA. Later on, the wording was modified to non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) because not all patients develop AS, what is now referred to as r-axSpA [5].

The Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) introduced the term 'axial spondyloarthritis' to encompass the disease's complete range, including patients with evident radiographic damage and those without [6].

While some studies suggest a SpA prevalence below 1% [7–9], it is thought that certain geographical regions can have a prevalence as high as 1.4% [10]. The discrepancies can be attributed to variations in the methodology and sample size, yet, it is widely recognized that the prevalence is significantly influenced by the underlying prevalence of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 [11]. The sex balance of SpA varies, with a male-to-female ratio of 2–3:1 [12]. There is a more even distribution of sexes in nr-axSpA, and the proportion of nr-axSpA is progressively rising, possibly due to improved diagnosis [13].

Aim

The aim of the article is to provide a comprehensive review of current understanding, obstacles, and advancements in the diagnosis, classification, monitoring, management, and involvement of multidisciplinary teams, and the incorporation of telehealth into the care of patients with axSpA. Through an in-depth exploration of the literature and research findings, this article seeks to elucidate the complexities of axSpA diagnosis, emphasize the importance of proper classification criteria, discuss various methods of monitoring disease activity and progression, assess both non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment approaches, and highlight the crucial function of multidisciplinary teams.

Search strategy

Relevant articles were retrieved from Medline/PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science using the search terms "spondyloarthritis" or "ankylosing spondylitis", and "diagnosis" or "classification" or "criteria" or "guidelines" or "imaging" or "treatment" or "management" or "telehealth". Only articles published in English until January 2024 were considered. No specific time frame was established. Following the listing of the articles, those that were not directly relevant to the issue were excluded. After the exclusion process, the authors analyzed the articles they deemed appropriate.

Diagnosis

AxSpA presents with a diverse range of clinical manifestations. Regrettably, no characteristic derived from the medical records, physical exam, test results, or radiologic evaluations possesses the necessary accuracy to diagnose axSpA definitively. Diagnosis entails identifying a collection of characteristic patterns and qualities that, when considered collectively, offer enough evidence to confirm the presence of axSpA [14].

The physician typically evaluates the probability of axSpA by balancing positive and negative test results in the accurate diagnostic procedure [15]. Early-stage identification of axSpA can provide challenges, especially before the conclusive diagnosis of radiological sacroiliitis. There is a suggestion to diagnose individuals at early phases using probability estimates derived from a 5% pretest probability in individuals with chronic back pain [16, 17].

Due to the complexities of mathematical modeling, Rudwaleit et al. [4] focused on utilizing positive likelihood ratios. The parameters exhibiting the most heightened positive likelihood ratio values include sacroiliitis verified through X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), family history or HLA-B27 positivity, and acute anterior uveitis [4]. However, absence of a specific characteristic can occasionally help rule out a diagnosis in routine diagnostic processes. In the case of axSpA, the non-existence of certain parameters significantly diminishes the likelihood of the diagnosis. These involve the absence of HLA-B27, negative MRI result, mismatch to the character of inflammatory back pain, typical acute phase reactants, unresponsiveness to NSAIDs, and, presumably, negative family history. Moreover, certain clinical signs may be absent in initial assessments. The clinical picture during the progression of the disease is primarily associated with the duration of the disease. These signs encompass inflammation in peripheral joints and soft tissues, ophthalmological involvement, skin and intestinal manifestations. The inclusion of these parameters contributes to a more accurate diagnosis. However, if they are not detected during the initial stages of the disease, they can be neglected [18].

Laboratory parameters are an integral part of diagnosing axSpA by assisting in thoroughly evaluating inflammatory processes and adding to the entire diagnostic framework. Assessment of acute-phase reactants is a standard practice [19, 20]. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of individuals with axSpA experience symptoms even when their acute-phase reactants are within normal range, with estimates suggesting that this occurs in up to 60% of patients [21]. Furthermore, the existence of HLA-B27, while not limited to axSpA, is an important indicator linked to axSpA. Although not used as a single diagnostic tool, the presence of HLA-B27 antigen is consistent with the diagnostic algorithm's clinical signs and imaging results [22, 23]. Incorporating these laboratory markers into a thorough clinical assessment is crucial for prompt diagnosis of axSpA.

Using radiologic assessment is essential for accurately and promptly diagnosing and differentiating axSpA. Since the disease commonly damages the sacroiliac joints, imaging these structures is essential in diagnosing [24].

For initial evaluation of suspected axSpA, it is advisable to arrange sacroiliac joints X-ray [25]. This is owing to the fact that X-rays are readily accessible. Conversely, the sensitivity of this test is limited, particularly in individuals who have experienced symptoms for a short period [26]. A significant concern associated with this approach is the limited reliability due to the intricate structure and individual variations in the visual representation of sacroiliac joints on conventional X-rays. The substantial inter-observer variability is also one of the drawback in the assessment of SIJ X-ray [27].

Computerized tomography (CT) is an emerging radiologic method widely recognized as the most reliable way to identify structural damage [28]. However, conventional CT cannot evaluate alterations related to inflammation in the sacroiliac joint [29].

If conventional radiographs fail to detect any signs of sacroilitis, and there is still suspicion of axSpA, it is recommended to perform sacroiliac joint MRI [25, 30]. The decision to incorporate the spine in the MRI depends on the clinical manifestations and potential diagnoses. The addition of spinal MRI does not significantly contribute to the diagnosis compared to sacroiliac joint MRI [31]. An essential benefit of MRI is its ability to identify active inflammatory changes, namely BME that might emerge before any structural damage. Furthermore, MRI is highly effective in accurately detecting structural alterations. Identifying BME of the sacroiliac joint enhances the probability of diagnosing axSpA, particularly when accompanied by structural alterations [32, 33]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that BME is not as indicative of axSpA as previously believed. Various disorders can lead to BME, e.g. intensive physical training and mechanical back pain [34].

Classification criteria

Classification criteria for axSpA have been developed for research purposes. In order to facilitate research, classification criteria are set consistently with the primary goal of producing clearly defined and homogeneous groups. The criteria used for classifying axSpA were established by ASAS in 2009 [35]. The ASAS axSpA criteria include sacroiliac joint MRI and apply to the full range of the condition (nr-axSpA and r-axSpA) [36]. An axSpA patient must exhibit persistent back pain lasting more than three months before the age of 45 in order to fulfill the entrance condition. Furthermore, to meet the criteria, a patient must exhibit sacroiliitis on imaging along with at least one additional SpA characteristic. Alternatively, a patient must test positive for HLA-B27 and have at least two SpA features.

Classification criteria may appear simple to apply as diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, their utilization for this objective is not advisable. Employing classification criteria for the diagnostic process not only disregards the crucial matter of differential diagnosis but also results in an unacceptably high rate of misdiagnoses, including both axSpA patients who are inaccurately overlooked and patients without axSpA who are inaccurately labeled as axSpA. The inherent restrictions in sensitivity and specificity are partially due to the categorical nature of these criteria that only determine if they are met [37, 38]. Additionally, several scholars contend that all characteristics are equally important, regardless of their varying value. The primary rationale for assigning equal weight was to ensure simplification and prioritize the ease of execution [39].

Monitoring

A wide range of options are currently accessible for monitoring axSpA. Most of the methods employed in axSpA rely on laboratory investigations, radiologic evaluations, and patient-reported results [40, 41].

Only patient-reported metrics are used in the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [42] to gauge disease activity in SpA. It was described in 1994 and has been utilized frequently, but certain restrictions exist. It does not consider healthcare professionals' opinion on the condition or the influence of individual clinical variables. The BASDAI is not sensitive enough to detect actual inflammation. The BASDAI has benefits, including its user-friendly nature and broad acceptance.

The Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) was developed as a composite index. This tool is characterized by integrating patient reports and acute phase reactants [43, 44]. The ASAS encourages the implementation of ASDAS-CRP in clinical settings and research activities. However, ESR-version may also be utilized. ASAS has established confirmed cut-off degrees for disease activity assertions. [45]. A decline of at least 1.1 across two evaluations is deemed a clinically important improvement, while a reduction of 2.0 is classified as a major improvement. Disease flare is characterized by a rise in the ASDAS of 0.9 or higher, in contrast to the prior evaluation [46]. Additional criteria for assessing response and remission include ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, and BASDAI 50 response [47–49].

The evaluation of an individual's physical function is a prerequisite for axSpA. During this process, the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) is the instrument that is utilized rather frequently. BASFI comprises ten questions, eight of which pertain to various parts of functional anatomy and two of which pertain to the capacity to deal with day-to-day life. Each of the ten questions contributes to the overall BASFI score (by averaging), which can vary from 0 to 10 [50].

One of the severe consequences of axSpA is the deterioration of spinal mobility, and it is recommended that this aspect be incorporated into the evaluation methods carried out on patients in clinical practices [24, 51]. Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) is a commonly used clinical tool for assessing spinal mobility. It includes examinations of movement in the spine and hips [52]. BASMI is a quantitative assessment tool used to quantify the course of spinal progression, explicitly focusing on non-imaging aspects. While BASMI measurements may be relatively straightforward to conduct, they require a significant amount of time and should be done in person by qualified healthcare professionals [53].

SpA-specific measures do not sufficiently evaluate the comprehensive assessment of disabilities, boundaries, and limitations in performing daily tasks or social engagement. The ASAS Health Index was created to evaluate complex well-being and quality of life in axSpA patients [54]. The ASAS Health Index is derived from 251 elements gathered via surveys on axSpA. It comprises 17 specific points [55, 56]. The main advantages and disadvantages of monitoring tools are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The main advantages and disadvantages of monitoring tools

| Tool | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| BASDAI |

• BASDAI has a user-friendly structure. • BASDAI is widely accepted. • BASDAI allows for a quick evaluation of disease activity. |

• BASDAI does not consider healthcare professionals' opinion. • BASDAI is not sensitive enough to detect actual inflammation. • BASDAI lacks objective measures. • BASDAI is subjective. |

| ASDAS |

• ASDAS is a composite index that merges patient-reported outcomes with acute-phase reactants. • ASDAS utilizes a standardized scoring structure. • ASDAS offers a quantitative and objective measurement of disease activity. |

• The complexity may be problematic in regular clinical practice. • ASDAS is dependent on laboratory tests. |

| BASFI |

• BASFI is an easily applicable tool. • It is a globally accepted and valid tool. • BASFI shows sensitivity to changes in functional status over time. |

• BASFI is based on subjective self-assessment. • BASFI necessitates individuals to recall. |

| BASMI |

• BASMI provides an objective assessment of spinal mobility. • BASMI uses standardized protocol. • BASMI evaluates multiple anatomical locations. |

• The assessment is based solely on clinical examination, without the utilization of imaging tools. • BASMI depends on the patient's ability to cooperate. • BASMI may encounter difficulty in detecting minor changes. |

| ASAS Health Index |

• ASAS Health Index provides a comprehensive assessment of health and well-being. • Aside from physical symptoms, the ASAS Health Index covers psychological and social impacts. • ASAS Health Index adheres to the ideals of patient-centered care. |

• ASAS Health Index is based on subjective responses. • It requires patients to recall. • It may lack the objectivity. |

BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, BASMI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index, ASAS Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society

Enthesitis is a usual feature of axSpA. The initial method for evaluating enthesitis is referred to as the Mander Enthesitis Index (MEI) [57]. The MEI quantifies the patient's reaction following localized exertion at 66 enthesal locations. The scoring is done. As an alternative, there have been suggestions for using more concise indices covering the Berlin Enthesitis Index (BEI) [58], Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada [59], Leeds Index [60], and the Maastricht AS Enthesitis Score (MASES) [61].

Only 30–40% of those affected exhibit increased acute-phase reactants, and it is essential to note that a normal value does not necessarily mean that inflammation is absent. When axSpA is accompanied with peripheral joint inflammation or inflammatory bowel disease, there is a higher occurrence of increased acute-phase reactants [21].

As previously stated, MRI is a highly sensitive tool for identifying signs of inflammation in the sacroiliac joints and spine. Nevertheless, regularly using these methods in rheumatology practice to monitor axSpA is not advisable as their incremental benefit compared to more suitable instruments has not been definitively established [25]. Various scoring systems have been created for scientific investigation. These scores are commonly employed to evaluate the treatment efficacy in clinical trials [62, 63].

The typical method for evaluating structural damage is through sacroiliac joint and spine radiography. However, there is no consensus on the specific procedure for conducting this assessment in clinical settings [25]. Different scoring methodologies have been suggested to evaluate the extent of radiological damage in axSpA. The most reliable and widely acknowledged tool is the modified Stoke AS Spine Score (mSASSS) [64, 65]. The mSASSS utilizes defined criteria to grade cervical and lumbar spine lateral plain radiographs. The overall score spans from 0 to 72.

Management

The care of axSpA patients involves both non-pharmacological and pharmacological procedures. An individualized strategy, tailored to particular requirements and backed by scientific evidence, is essential [66]. Integrating both intervention groups (non-pharmacological and pharmacological) is crucial for axSpA [67]. The treatment strategy should strive to attain the utmost level of quality of life and patients’ health status assessment [68]. Due to the inflammatory nature of axSpA, a considerable amount of existing treatments focus on decreasing the inflammatory load. Furthermore, considering the influence of disease severity on both structural damage and functional status, it is crucial to prioritize the handling of inflammation in the treatment [69, 70]. A pre-established, targeted therapeutic approach, mutually agreed upon by the patient and physician, proves beneficial. In axSpA, the link between increasing ASDAS scores and a higher incidence of syndesmophytes indicates that ASDAS is a suitable focus for intervention [71].

Non-pharmacological therapies

AxSpA patients should engage in a comprehensive educational initiative regarding the disease. The main goal of self-management is to engage and enable patients to collaborate proactively. In a broader sense, patient education should encompass knowledge regarding the disorder, its signs and identification, progression, available treatment alternatives, and future directions [72].

Physical activity—exercise is a fundamental aspect of treating axSpA. Although exercise is typically included in the management approach, qualitative research indicates compliance improves when supervised [67, 73]. Although exercise interventions have shown impressive outcomes in investigations, aggressive exercise programs may adversely affect axSpA patients. Mechanical overloading can potentially increase inflammation and the development of additional bone formation in the enthesal and joint areas [73]. Studies utilizing computer modeling have demonstrated a model of syndesmophyte formation in areas of high mechanical stress in the spine in patients with long-term AS using computerized tomography scanning [74]. However, a definitive link between exercise and the development of syndesmophytes has not been established. Hence, exercise, a fundamental component of axSpA management, should not be abandoned.

Modifying detrimental lifestyle behaviors is crucial in the management of axSpA. Suggestions for lifestyle practices to prevent disease progression encompass adhering to a nutritious and well-balanced diet, keeping an optimal body weight [75]. Research has demonstrated that smoking is a contributing factor to the advancement of spinal inflammation and structural damage in axSpA [76, 77]. Hence, it is essential to motivate axSpA patients to quit smoking.

Pharmacological therapies

NSAIDs are the primary choice for managing axSpA with a pharmacologic approach. Individuals who suffer from pain and stiffness should carefully evaluate the hazards and benefits of utilizing NSAIDs at the maximum acceptable and tolerable doses [66]. If it is deemed necessary to control signs, the ongoing utilization of NSAIDs can be contemplated in individuals who suffer from symptoms. However, around one-third of patients demonstrate either nonresponsiveness or intolerance toward NSAIDs [78]. Concerning the effectiveness of NSAIDs in reducing structural damage, research up to this point has produced contradictory results. Compared to patients who received NSAIDs as needed, those with r-axSpA who were treated continually for two years with NSAIDs (primarily celecoxib) had retarded radiological progress [79]. This finding was not supported in a subsequent investigation of diclofenac [80]. Furthermore, continuous celecoxib and golimumab in combination therapy did not provide any meaningful advantage over golimumab alone in reducing structural deterioration in r-axSpA over two years [81]. Clinical improvement resulting from the administration of the full dose of NSAIDs is frequently noted within two weeks. If there is no sufficient response within this time, it is advisable to consider using a second NSAID. Currently, there is inadequate data to determine if alternating between standard NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors is superior to using a second NSAID from the same category [82].

In patients who continue to experience high disease activity after taking two NSAIDs at adequate doses and duration, biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs) can be considered [66]. Two classes of bDMARDs, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) and interleukin 17 inhibitor (IL-17i), and one class of tsDMARD, janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), have been approved. Without direct comparative clinical trials, it is challenging to determine the relative effectiveness of different choices and establish a clear priority. Nevertheless, it is widely recognized that initiating treatment with a TNFi or IL-17i is a customary approach [66]. This assertion is supported by extensive prior experience with TNFi and IL-17i, robust and comprehensive evidence, a wealth of safety data, and considerable familiarity with these medications in patients with numerous comorbidities, typically excluded to ensure homogeneity in high-quality trials.

TNFi has been a treatment option, and infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been approved for axSpA. Infliximab has been approved exclusively for r-axSpA whereas the others have been approved for nr-axSpA and r-axSpA [83]. Evidence indicates this class of drugs has substantial benefits over placebo in controlling disease activity, enhancing functionality, and reaching partial remission [84]. According to an extensive European database of individuals with axSpA who started their initial TNFi medication as part of their regular management, 27% of individuals reached ASDAS inactive disease following six months, and 59% obtained BASDAI < 4. After a year, four out of five individuals were still receiving medication [85]. The efficacy of TNFi drugs has also been evidenced by a decrease in inflammation observed on sacroiliac MRI [86]. Comparable patterns have been exhibited in reducing inflammation in the spinal vertebrae when subjected to TNFi therapy [87].

Incorporating IL-17i in rheumatology has expanded the pharmacological armamentarium available for axSpA. Currently, secukinumab and ixekizumab have been approved [66]. Secukinumab and ixekizumab were more effective than placebo in an evaluation based on ASAS40 responses [88]. IL-17i has demonstrated effectiveness in individuals who previously received TNFi treatment, albeit with reduced efficacy compared to those without TNFi treatment [89]. Although TNFi and IL-17i alleviate axSpA symptoms with favorable safety characteristics, there is currently no sufficient data to suggest that one is more effective.

Tofacitinib exhibited superior efficacy over placebo in active axSpA at week 16 as determined by an analysis based on the ASAS40 response [90]. The investigation on upadacitinib's effects on active r-axSpA yielded comparable outcomes [91]. An advantage of these treatment options is their oral administration. Moreover, upadacitinib demonstrated a substantial enhancement in nr-axSpA symptoms as compared to placebo during the week 14 evaluation [92].

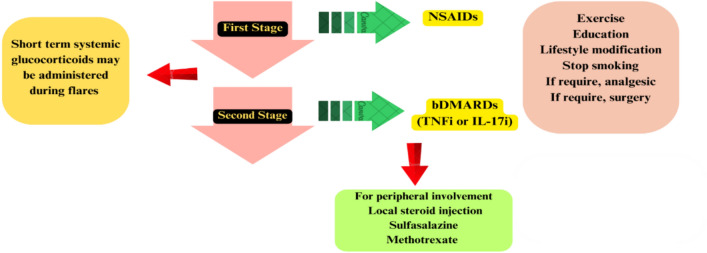

There is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of csDMARDs in managing axSpA. Extended care for axial signs is not supportive of systemic glucocorticoids. However, systemic glucocorticoids may be administered during disease flares marked by increased disease activity, inflammation, and pain. There is evidence to suggest the efficacy of high dosages of systemic glucorticoids, and this could be a beneficial addition to the axial SpA armamentarium [93]. In some cases, this method may be effective for short-term disease control. Short-term use of high-dose or pulsed systemic glucocorticoids may be part of SpA's therapeutic repertory to handle severe axSpA flares that are unresponsive and debilitating to NSAIDs when biologics are unavailable or inappropriate. When administered in the short term, its benefits in reducing severe pain and stiffness and improving mobility are expected to outweigh bone loss and other adverse effects [94]. Additionally, intra-articular injections may be taken into consideration. In certain instances, local injections can be efficacious for patients experiencing enthesitis. Paracetamol and opioids can be utilized for pain that continues despite the standard treatment strategy [66] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Axial spondyloarthritis treatment approach. NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bDMARDs biolgical disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, TNFi tumour necrosis factor inhibitors; IL-17i IL-17 inhibitors

Optimal treatment options for particular subsets

Although bDMARDs and tsDMARDs have comparable effectiveness in managing the axSpA, there are notable distinctions in their effectiveness for non-musculoskeletal manifestations [95]. In cases of recurring uveitis or persistent inflammatory bowel disease, anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies are preferable [96]. Although etanercept has presented contradictory outcomes, monoclonal TNFi (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab) treatment can be evaluated for individuals who do not benefit from conventional treatment in managing acute anterior uveitis [66]. When analyzing etanercept and secukinumab for uveitis exacerbation prevention, registry data investigations demonstrated that monoclonal anti-TNF agents were superior [97]. IL-17i is not recommended in clinical scenarios where axSpA is coupled with inflammatory bowel disease [98]. Considering the positive impact of IL-17i on skin signs of psoriasis, they might be a more suitable option than TNF inhibitors for individuals with severe skin conditions [99, 100]. Evidence has demonstrated JAKi's tofacitinib efficacy in treating chronic plaque psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.

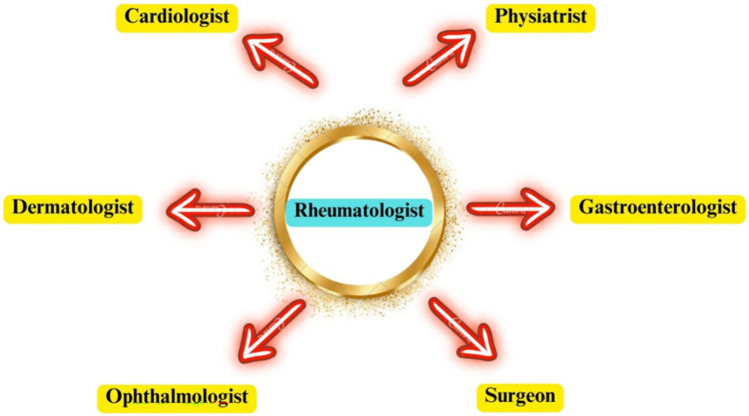

Role of the multidisciplinary team in the management

Effective management of axSpA requires a thorough and well-coordinated strategy, highlighting the crucial importance of a multidisciplinary team. The intricate nature of SpA, with its wide range of clinical presentations and influence on multiple facets of patients' well-being, necessitates the involvement of professionals from various healthcare disciplines to ensure efficient treatment [66, 101]. The multidisciplinary team typically comprises rheumatologists, rehabilitation specialists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dermatologists, gastroenterologists, ophthalmologists, cardiologists, and, if needed, orthopedic surgeons and pain medicine experts [102–104] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Multidisciplinary team in axial spondyloarthritis management

The primary advantage of utilizing a multidisciplinary team to manage axSpA is the capacity to effectively address each aspect of the disease. Rheumatologists are the primary professionals responsible for diagnosing, managing, and monitoring disorders [66]. Rehabilitation specialists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists are crucial in improving physical function and mobility as part of the complete treatment strategy [105, 106]. Considering the involvement of SpA, it is evident that the input of dermatologists, gastroenterologists, ophthalmologists, and cardiologists is required. Orthopedic surgeons are typically involved in cases that require surgical procedures [107].

The effects of axSpA go beyond physical manifestations and encompass psychological and social aspects [108, 109]. Psychologists and social workers are essential members of the multidisciplinary team, as they address mental health issues and assist patients in managing the difficulties associated with living with a persistent inflammatory disease.

Continuous and coordinated interaction among team members provides an efficient and patient-focused strategy. This collaborative endeavor allows a more nuanced comprehension of the patient's condition and promotes tailored care regimens. The advantages of employing a multidisciplinary approach in managing SpA include efficient disease management, improved quality of life, and decreased long-term disability [110]. In addition, the multidisciplinary team can aid in the early identification of complications and rapid care, thereby preventing irreversible damage.

Telehealth

Remote healthcare utilizes technological advances known as 'telehealth' operations [111]. Interaction with patients and caregivers is employed throughout the patient journey, encompassing disease assessment and monitoring various elements of the disease, such as disease severity and progression, deterioration, quality of life, and compliance [112]. Transmission can occur either synchronously, with both the health professional and patient accessible simultaneously, or asynchronously, through videos, storage-transmission of medical events, and monitoring of the patients remotely [113].

Diagnostic delay is a severe challenge in axSpA. Utilizing asynchronous telemedicine solutions can effectively address this issue. Obtaining radiologic images is crucial at this juncture [114]. Integrating electronic patient-reported outcomes allows for remote and standardized evaluation of treatment effectiveness and rapid modifications to the treatment plan. Patients with high disease activity demonstrate a strong commitment to monitoring their electronic patient-reported outcomes. Additionally, there is an agreement between the printed and digital BASDAI [115, 116]. A systematic review of rheumatic diseases concluded that remote care yielded comparable or superior results in effectiveness, safety, patient compliance, and user satisfaction outcomes compared to in-person care. However, the existing studies exhibit heterogeneity in methodology, and there is an elevated risk of bias in favor of specific outcomes [117]. In telehealth applications, online physiotherapy can be considered a worthwhile option for axSpA patients [118].

Conclusion and future perspectives

The care of axSpA requires a comprehensive and multifaceted strategy involving diagnosis, monitoring, and therapeutic interventions. Due to the lack of a single reliable test, diagnosing axSpA remains challenging. Clinical, laboratory, and imaging aspects all contribute to the diagnosis. Monitoring axSpA demands the utilization of several assessment tools, and the involvement of a multidisciplinary team is essential in managing diverse manifestations of axSpA.

Additional endeavors should be undertaken to ascertain the axSpA's initial stages, especially where there is a risk of over-diagnosis nr-axSpA. Considering the diagnostic delay, often due to under-diagnosis, it is crucial to prioritize early detection and create appropriate interventions accordingly. To achieve early diagnosis, it is essential to strive for optimal imaging use and additional biomarkers. The most effective ways to monitor disease activity and clinical changes in conjunction with technological advancements should be identified. Attempts should also be made to clarify how to select the best patients who would benefit the most from different treatment methods.

Author contribution

Study design: OZ, BFK, and MK. Data acquisition and review of the literature: OZ, and BFK. Making interpretations: OZ, BFK, and MK. Drafting the manuscript: OZ, BFK, and MK. Critically reviewing the manuscript: OZ, BFK, and MK. Final approval: OZ, BFK, and MK.

Funding

This work has been supported by a grant entitled 'The POLish NORwegian research collaboration to increase quality of health care and improve health outcomes of children and adult patients with RHEUMAtological diseases' (POLNOR-RHEUMA) 0026/2019–00 from the National Center for Research and Development (NCBiR).” and “Support program for Ukrainian researchers" (POLNOR-RHEUMA ‘UA’) FWD/II/118/POLNOR-RHEUMA_UA/2022 from the National Center for Research and Development (NCBiR).”

Data availability

There is no stored data set associated with the article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conficts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Navarro-Compán V, Sepriano A, El-Zorkany B, van der Heijde D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1511–1521. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucybała I, Urbanik A, Wojciechowski W. Radiologic approach to axial spondyloarthritis: where are we now and where are we heading? Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:1753–1762. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1000–1008. doi: 10.1002/art.20990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MA, van der Linden S. Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Better Name for an Old Disease: A Step Toward Uniform Reporting. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019;1:336–339. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudwaleit M, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:770–776. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citera G, Bautista-Molano W, Peláez-Ballestas I, Azevedo VF, Perich RA, Méndez-Rodríguez JA, Cutri MS, Borlenghi CE. Prevalence, demographics, and clinical characteristics of Latin American patients with spondyloarthritis. Adv Rheumatol. 2021;61:2. doi: 10.1186/s42358-020-00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costantino F, Talpin A, Said-Nahal R, Goldberg M, Henny J, Chiocchia G, Garchon HJ, Zins M, Breban M. Prevalence of spondyloarthritis in reference to HLA-B27 in the French population: results of the GAZEL cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:689–693. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tłustochowicz M, Brzozowska M, Wierzba W, Raciborski F, Kwiatkowska B, Tłustochowicz W, Jacyna A, Marczak M, Kisiel B, Śliwczyński A. Prevalence of axial spondyloarthritis in Poland. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:323–330. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Medina C, Moltó A. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors, and disease outcomes of axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boel A, van Lunteren M, López-Medina C, Sieper J, van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA. Geographical prevalence of family history in patients with axial spondyloarthritis and its association with HLA-B27 in the ASAS-PerSpA study. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002174. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-002174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougados M, Etcheto A, Molto A, et al. Clinical presentation of patients suffering from recent onset chronic inflammatory back pain suggestive of spondyloarthritis: The DESIR cohort. Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieper J, van der Heijde D. Review: Nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis: new definition of an old disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:543–551. doi: 10.1002/art.37803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Gaalen FA, Rudwaleit M. Challenges in the diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2023;37:101871. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2023.101871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poddubnyy D. Classification vs diagnostic criteria: the challenge of diagnosing axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology. 2020 doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan MA, Braun J, Sieper J. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:535–543. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.011247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adshead R, Donnelly S, Knight P, Tahir H. Axial Spondyloarthritis: Overcoming the Barriers to Early Diagnosis-an Early Inflammatory Back Pain Service. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22:59. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudwaleit M, Feldtkeller E, Sieper J. Easy assessment of axial spondyloarthritis (early ankylosing spondylitis) at the bedside. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1251–1252. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.051045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzin M, Ometto F, Ortolan A, Felicetti M, Favero M, Doria A, Ramonda R. An update on serum biomarkers to assess axial spondyloarthritis and to guide treatment decision. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1759720X20934277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Berg R, de Hooge M, van Gaalen F, Reijnierse M, Huizinga T, van der Heijde D. Percentage of patients with spondyloarthritis in patients referred because of chronic back pain and performance of classification criteria: experience from the Spondyloarthritis Caught Early (SPACE) cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:1492–1499. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spoorenberg A, van der Heijde D, de Klerk E, Dougados M, de Vlam K, Mielants H, van der Tempel H, van der Linden S. Relative value of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in assessment of disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:980–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coates LC, Baraliakos X, Blanco FJ, et al. The phenotype of axial spondyloarthritis: is it dependent on HLA-B27 status? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:856–860. doi: 10.1002/acr.24174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett AN, McGonagle D, O'Connor P, Hensor EM, Sivera F, Coates LC, Emery P, Marzo-Ortega H. Severity of baseline magnetic resonance imaging-evident sacroiliitis and HLA-B27 status in early inflammatory back pain predict radiographically evident ankylosing spondylitis at eight years. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3413–3418. doi: 10.1002/art.24024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, Dougados M, Hermann KG, Landewé R, Maksymowych W, van der Heijde D. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1–44. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandl P, Navarro-Compán V, Terslev L, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the diagnosis and management of spondyloarthritis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1327–1339. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poddubnyy D, Brandt H, Vahldiek J, Spiller I, Song IH, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J. The frequency of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in relation to symptom duration in patients referred because of chronic back pain: results from the Berlin early spondyloarthritis clinic. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1998–2001. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diekhoff T, Hermann KG, Greese J, Schwenke C, Poddubnyy D, Hamm B, Sieper J. Comparison of MRI with radiography for detecting structural lesions of the sacroiliac joint using CT as standard of reference: results from the SIMACT study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1502–1508. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stal R, van Gaalen F, Sepriano A, Braun J, Reijnierse M, van den Berg R, van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X. Facet joint ankylosis in r-axSpA: detection and 2-year progression on whole spine low-dose CT and comparison with syndesmophyte progression. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:3776–3783. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diekhoff T, Eshed I, Radny F, Ziegeler K, Proft F, Greese J, Deppe D, Biesen R, Hermann KG, Poddubnyy D. Choose wisely: imaging for diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:237–242. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee YJ, Lee SH, Ahn SM, Hong S, Oh JS, Lee CK, Yoo B, Kim YG. When MRI would be useful in patients without evidence of sacroiliitis on radiographs? Rheumatol Int. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s00296-023-05468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ez-Zaitouni Z, Bakker PA, van Lunteren M, et al. The yield of a positive MRI of the spine as imaging criterion in the ASAS classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis: results from the SPACE and DESIR cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1731–1736. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukas C, Cyteval C, Dougados M, Weber U. MRI for diagnosis of axial spondyloarthritis: major advance with critical limitations 'Not everything that glisters is gold (standard)'. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000586. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almodóvar R, Bueno Á, Batlle E, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: development of checklists for use in clinical practice. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:2119–2127. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Winter J, de Hooge M, van de Sande M, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Sacroiliac Joints Indicating Sacroiliitis According to the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society Definition in Healthy Individuals, Runners, and Women With Postpartum Back Pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:1042–1048. doi: 10.1002/art.40475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–783. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert RG, Bakker PA, van der Heijde D, et al. Defining active sacroiliitis on MRI for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: update by the ASAS MRI working group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1958–1963. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:891–897. doi: 10.1002/acr.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landewé RB, van der Heijde DM. Why CAPS criteria are not diagnostic criteria? Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:e7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubreuil M, Deodhar AA. Axial spondyloarthritis classification criteria: the debate continues. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:317–322. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landewé R, van Tubergen A. Clinical Tools to Assess and Monitor Spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:47. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reveille JD. Biomarkers for diagnosis, monitoring of progression, and treatment responses in ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1009–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-2949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michielsens C, Bolhuis TE, van Gaalen FA, van den Hoogen F, Verhoef LM, den Broeder N, den Broeder AA. Construct validity of Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) treatment target cut-offs in a BASDAI treat-to-target axial spondyloarthritis cohort: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2024;53:180–187. doi: 10.1080/03009742.2023.2213509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, Sieper J, Van den Bosch F, Listing J, Braun J, Landewé R; Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1811–1818. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sundaram TG, Muhammed H, Aggarwal A, Gupta L. A prospective study of novel disease activity indices for ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1843–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04662-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, Kvien TK, Braun J, Baker D, van der Heijde D; Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease activity states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Molto A, Gossec L, Meghnathi B, Landewé RBM, van der Heijde D, Atagunduz P, Elzorkany BK, Akkoc N, Kiltz U, Gu J, Wei JCC, Dougados M, ASAS-FLARE study group, An Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS)-endorsed definition of clinically important worsening in axial spondyloarthritis based on ASDAS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:124–127. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Navarro-Compán V, Ramiro S, Deodhar A, Mease PJ, Rudwaleit M, de la Loge C, Fleurinck C, Taieb V, Mørup MF, Massow U, Kay J, Magrey M. Association of clinical response criteria and disease activity levels with axial spondyloarthritis core domains: results from two phase 3 randomised studies, BE MOBILE 1 and 2. RMD Open. 2024;10:e004040. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2023-004040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brandt J, Listing J, Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Braun J. Development and preselection of criteria for short term improvement after anti-TNF alpha treatment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1438–1444. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Braun J, Davis J, Dougados M, Sieper J, van der Linden S, van der Heijde D; ASAS Working Group First update of the international ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:316–320. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hallström M, Klingberg E, Deminger A, Rehnman JB, Geijer M, Forsblad-d'Elia H. Physical function and sex differences in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a cross-sectional analysis on Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25:182. doi: 10.1186/s13075-023-03173-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carvalho PD, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Fonseca J, Marreiros A, Machado PM. Determining factors related to impaired spinal and hip mobility in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: longitudinal results from the DESIR cohort. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001356. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biallas RL, Dean LE, Davidson L, Hollick R, Pathan E, Robertson L, Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ, Rotariu O. Role of metrology in axial spondyloarthritis: does it provide unique information in assessing patients and predicting outcome? results from the British society for rheumatology biologic register for ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022;74:665–674. doi: 10.1002/acr.24500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castro MP, Stebbings SM, Milosavljevic S, Bussey MD. Construct validity of clinical spinal mobility tests in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1777–1787. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, et al. Development of a health index in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (ASAS HI): final result of a global initiative based on the ICF guided by ASAS. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:830–835. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Carlo M, Lato V, Di Matteo A, Carotti M, Salaffi F. Defining functioning categories in axial Spondyloarthritis: the role of the ASAS Health Index. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:713–718. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3642-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akgul O, Bodur H, Ataman S, Yurdakul FG, et al. Clinical performance of ASAS Health Index in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: real-world evidence from Multicenter Nationwide Registry. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1793–1801. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mander M, Simpson JM, McLellan A, Walker D, Goodacre JA, Dick WC. Studies with an enthesis index as a method of clinical assessment in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987;46:197–202. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.3.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maksymowych WP, Mallon C, Morrow S, Shojania K, Olszynski WP, Wong RL, Sampalis J, Conner-Spady B. Development and validation of the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:948–953. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Healy PJ, Helliwell PS. Measuring clinical enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis: assessment of existing measures and development of an instrument specific to psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:686–691. doi: 10.1002/art.23568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heuft-Dorenbosch L, Spoorenberg A, van Tubergen A, Landewé R, van ver Tempel H, Mielants H, Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Assessment of enthesitis in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:127–132. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lukas C, Braun J, van der Heijde D, Hermann KG, et al. Scoring inflammatory activity of the spine by magnetic resonance imaging in ankylosing spondylitis: a multireader experiment. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:862–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Salonen D, Dhillon SS, Williams M, Stone M, Conner-Spady B, Palsat J, Lambert RG. Spondyloarthritis research Consortium of Canada magnetic resonance imaging index for assessment of sacroiliac joint inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:703–709. doi: 10.1002/art.21445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Creemers MC, Franssen MJ, Vant Hof MA, Gribnau FW, Van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Assessment of outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: an extended radiographic scoring system. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:127–129. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cengiz M, Ataman Ş, Sunar İ, Yalçın AP, Yılmaz G, Elhan AH. Evaluation of the early cervical structural change in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthropathy. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:495–502. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04807-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:19–34. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ortolan A, Webers C, Sepriano A, Falzon L, Baraliakos X, Landewé RB, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, Nikiphorou E. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological and non-biological interventions: a systematic literature review informing the 2022 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:142–152. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hirano F, van der Heijde D, van Gaalen FA, Landewé RBM, Gaujoux-Viala C, Ramiro S. Determinants of the patient global assessment of well-being in early axial spondyloarthritis: 5-year longitudinal data from the DESIR cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:316–321. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, van Tubergen A, Stolwijk C, Dougados M, van den Bosch F, Landewé R. Higher disease activity leads to more structural damage in the spine in ankylosing spondylitis: 12-year longitudinal data from the OASIS cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1455–1461. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Landewé R, Dougados M, Mielants H, van der Tempel H, van der Heijde D. Physical function in ankylosing spondylitis is independently determined by both disease activity and radiographic damage of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:863–867. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, et al. 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1251–1260. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:954–962. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ansell RC, Shuto T, Busquets-Perez N, Hensor EM, Marzo-Ortega H, McGonagle D. The role of biomechanical factors in ankylosing spondylitis: the patient's perspective. Reumatismo. 2015;67:91–96. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2015.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan S, Dasgupta A, Yao J, Flynn JA, Yao L, Ward MM. Spatial distribution of syndesmophytes along the vertebral rim in ankylosing spondylitis: preferential involvement of the posterolateral rim. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1951–1957. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Balanescu A, et al. 2021 EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:48–56. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Poddubnyy D, Haibel H, Listing J, Märker-Hermann E, Zeidler H, Braun J, Sieper J, Rudwaleit M. Baseline radiographic damage, elevated acute-phase reactant levels, and cigarette smoking status predict spinal radiographic progression in early axial spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1388–1398. doi: 10.1002/art.33465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramiro S, Landewé R, van Tubergen A, Boonen A, Stolwijk C, Dougados M, van den Bosch F, van der Heijde D. Lifestyle factors may modify the effect of disease activity on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a longitudinal analysis. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000153. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baraliakos X, Kiltz U, Peters S, et al. Efficiency of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs according to current recommendations in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:95–102. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wanders A, Dv H, Landewé R, Béhier JM, Calin A, Olivieri I, Zeidler H, Dougados M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1756–1765. doi: 10.1002/art.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sieper J, Listing J, Poddubnyy D, Song IH, Hermann KG, Callhoff J, Syrbe U, Braun J, Rudwaleit M. Effect of continuous versus on-demand treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with diclofenac over 2 years on radiographic progression of the spine: results from a randomised multicentre trial (ENRADAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1438–1443. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Proft F, Muche B, Listing J, Rios-Rodriguez V, Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Study protocol: Comparison of the effect of treatment with Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs added to anti-tumour necrosis factor a therapy versus anti-tumour necrosis factor a therapy alone on progression of structural damage in the spine over two years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (CONSUL)—an open-label randomized controlled multicenter trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014591. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Regel A, Sepriano A, Baraliakos X, van der Heijde D, Braun J, Landewé R, Van den Bosch F, Falzon L, Ramiro S. Efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological and non-biological pharmacological treatment: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000397. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2016-000397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harrison SR, Marzo-Ortega H. Have therapeutics enhanced our knowledge of axial spondyloarthritis? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2023;25:56–67. doi: 10.1007/s11926-023-01097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shentu H, Sha S, He Y, He M, Dong N, Huang Z, Lai H, Chen M, Huang J, Huang X. Efficacy of TNF-α inhibitors in the treatment of nr-axSpA: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2024;1:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000536601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ørnbjerg LM, Brahe CH, Askling J, et al. Treatment response and drug retention rates in 24 195 biologic-naïve patients with axial spondyloarthritis initiating TNFi treatment: routine care data from 12 registries in the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1536–1544. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barkham N, Keen HI, Coates LC, O'Connor P, Hensor E, Fraser AD, Cawkwell LS, Bennett A, McGonagle D, Emery P. Clinical and imaging efficacy of infliximab in HLA-B27-Positive patients with magnetic resonance imaging-determined early sacroiliitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:946–954. doi: 10.1002/art.24408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garcia-Montoya L, Emery P. Disease modification in ankylosing spondylitis with TNF inhibitors: spotlight on early phase clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021;30:1109–1124. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.2010187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yin Y, Wang M, Liu M, Zhou E, Ren T, Chang X, He M, Zeng K, Guo Y, Wu J. Efficacy and safety of IL-17 inhibitors for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22:111. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02208-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: sixteen-week results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:599–611. doi: 10.1002/art.40753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Deodhar A, Sliwinska-Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1004–1013. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van der Heijde D, Song IH, Pangan AL. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394:2108–2117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deodhar A, Van den Bosch F, Poddubnyy D, et al. Upadacitinib for the treatment of active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SELECT-AXIS 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haibel H, Fendler C, Listing J, Callhoff J, Braun J, Sieper J. Efficacy of oral prednisolone in active ankylosing spondylitis: results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled short-term trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:243–246. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dhir V, Mishra D, Samanta J. Glucocorticoids in spondyloarthritis-systematic review and real-world analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:4463–4475. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ma KS, Lee YH, Lin CJ, Shih PC, Wei JC. Management of extra-articular manifestations in spondyloarthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2023;26:183–186. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Evangelatos G, Bamias G, Kitas GD, Kollias G, Sfikakis PP. The second decade of anti-TNF-a therapy in clinical practice: new lessons and future directions in the COVID-19 era. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:1493–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00296-022-05136-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lindström U, Bengtsson K, Olofsson T, Di Giuseppe D, Glintborg B, Forsblad-d'Elia H, Jacobsson LTH, Askling J. Anterior uveitis in patients with spondyloarthritis treated with secukinumab or tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in routine care: does the choice of biological therapy matter? Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1445–1452. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Reich K, Deodhar AA, McInnes IB, Porter B, Das Gupta A, Pricop L, Fox T. Incidence rates of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis treated with secukinumab: a retrospective analysis of pooled data from 21 clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:473–479. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mease PJ, Smolen JS, Behrens F, et al. A head-to-head comparison of the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab and adalimumab in biological-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a randomised, open-label, blinded-assessor trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:123–131. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.McInnes IB, Behrens F, Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (EXCEED): a double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1496–1505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30564-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Boonen A. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:65–73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kjeken I, Bø I, Rønningen A, Spada C, Mowinckel P, Hagen KB, Dagfinrud H. A three-week multidisciplinary in-patient rehabilitation programme had positive long-term effects in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:260–267. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rademacher J, Müllner H, Diekhoff T, Haibel H, Igel S, Pohlmann D, Proft F, Protopopov M, Rios Rodriguez V, Torgutalp M, Pleyer U, Poddubnyy D. Keep an eye on the back: spondyloarthritis in patients with acute anterior uveitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75:210–219. doi: 10.1002/art.42315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aghdam MRF, Vodovnik A, Hameed RA. Role of telemedicine in multidisciplinary team meetings. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:35. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_20_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Das P, Haldar R, Santhanam S. Therapeutic exercises and rehabilitation in axial spondyloarthropathy: Balancing benefits with unique challenges in the Asia-Pacific countries. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24(2):170–182. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klemm P, Preusler P, Hudowenz O, Asendorf T, Müller-Ladner U, Neumann E, Lange U, Tarner IH. Multimodal rheumatologic complex treatment in patients with spondyloarthritis - a prospective study. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;93:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gudu T, Jadon DR. Multidisciplinary working in the management of axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720X20975888. doi: 10.1177/1759720X20975888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Garrido-Cumbrera M, Bundy C, Navarro-Compán V, Makri S, Sanz-Gómez S, Christen L, Mahapatra R, Delgado-Domínguez CJ, Poddubnyy D. Patient-reported impact of axial spondyloarthritis on working life: results from the european map of axial spondyloarthritis survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:1826–1833. doi: 10.1002/acr.24426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wilson N, Liu J, Adamjee Q, Di Giorgio S, Steer S, Hutton J, Lempp H. Exploring the emotional impact of axial Spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies and a review of social media. BMC Rheumatol. 2023;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s41927-023-00351-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.So H, Tam LS. Cardiovascular disease and depression in psoriatic arthritis: Multidimensional comorbidities requiring multidisciplinary management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2021;35:101689. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2021.101689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ahmed S, Grainger R, Santosa A, et al. APLAR recommendations on the practice of telemedicine in rheumatology. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:247–258. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mago A, Aggarwal V, Gupta L. Telerheumatology and its interplay with patient-initiated care. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1883–1884. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04930-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.de Thurah A, Bosch P, Marques A, et al. 2022 EULAR points to consider for remote care in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1065–1071. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2022-222341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hannah L, von Sophie R, Gabriella RM, et al. Stepwise asynchronous telehealth assessment of patients with suspected axial spondyloarthritis: results from a pilot study. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00296-023-05360-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.von Rohr S, Knitza J, Grahammer M, Schmalzing M, Kuhn S, Schett G, Ramming A, Labinsky H. Student-led clinics and ePROs to accelerate diagnosis and treatment of patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a prospective pilot study. Rheumatol Int. 2023;43:1905–1911. doi: 10.1007/s00296-023-05392-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kempin R, Richter JG, Schlegel A, Baraliakos X, Tsiami S, Buehring B, Kiefer D, Braun J, Kiltz U. Monitoring of disease activity with a smartphone app in routine clinical care in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:878–884. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.211116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Marques A, Bosch P, de Thurah A, et al. Effectiveness of remote care interventions: a systematic review informing the 2022 EULAR Points to Consider for remote care in rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002290. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2022-002290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paul L, McDonald MT, McConnachie A, Siebert S, Coulter EH. Online physiotherapy for people with axial spondyloarthritis: quantitative and qualitative data from a cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s00296-023-05456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There is no stored data set associated with the article.