Abstract

Purpose

To assess the relationship of optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings and progression to foveal atrophy in a cohort of eyes with extrafoveal geographic atrophy (GA) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) at inclusion.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 45 participants (45 eyes) with extrafoveal GA at baseline and with 2 years of regular follow-ups. Several OCT qualitative features (i.e., presence of foveal flat pigment epithelium detachment with a thin double layer sign [DLS] and reticular pseudodrusen, GA focality) and quantitative measurements (outer retinal layer thickness, retinal pigment epithelium [RPE] to Bruch’s membrane [BM] volume, minimum distance from the central foveal circle, and untransformed GA lesion size area) were assessed at baseline. Logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify independent significant predictors and compute odds ratios (ORs) for the risk of the development of atrophy.

Results

At month 24, 26 eyes (57.8%) developed atrophy in the foveal central circle, while 11 eyes (24.4%) developed atrophy in the foveal central point. Significant independent predictive features for the development of atrophy in the foveal central circle included foveal outer retinal thickness (OR, 0.867; p = 0.015), minimum distance from the foveal central circle (OR, 0.992; p = 0.022), and foveal thin DLS (OR, 0.044; p = 0.036). The only independent predictive feature for the development of atrophy in the foveal central point was the presence of foveal thin DLS (OR, 0.138; p = 0.017).

Conclusions

We identified OCT risk factors for 2-year foveal atrophy in eyes with untreated extrafoveal GA at baseline.

Keywords: Optical coherence tomography, Geographic atrophy, Age-related macular degeneration, Biomarkers

Introduction

Geographic atrophy (GA) is the non-neovascular form of late age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [1]. GA is responsible for 10 to 20% of cases of legal blindness in patients with AMD [2] and it is estimated to affect more than 5 million people worldwide with a prevalence increasing exponentially with age [3].

Even though GA is a complex disease entity with multifactorial etiologies, this disorder is ultimately characterized by loss of the outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choriocapillaris (CC) [4]. Although GA may affect the fovea at initial diagnosis, patches of atrophy typically involve the parafoveal macula at the beginning. This phenomenon, known as foveal sparing, characterizes a form of GA referred to as extrafoveal GA [5]. Of note, the term foveal-sparing GA is confined to extrafoveal GA cases with RPE atrophy surrounding the fovea by more than 270°. Previous studies have speculated that preferential foveal sparing may be secondary to the lower susceptibility of cone photoreceptors to cell death in the setting of AMD [6].

Importantly, assuming that GA regions are associated with corresponding absolute scotomas [7], central visual function typically remains unaffected until GA reaches the fovea [8]. Therefore, progression with respect to the distance to the fovea is a key determinant of visual prognosis in patients with extrafoveal GA at baseline. Of note, although the median time required for extrafoveal GA from first appearance to foveal center involvement is around 2.5 years [9], this period may be quite variable in clinical practice.

Assuming that the complement system appears to be involved in the GA pathogenesis and progression [10], complement inhibitors have been evaluated in clinical trials to understand whether these therapies are effective in slowing GA progression [11]. Following favorable results obtained in clinical trials [12], the use of an intravitreal complement C3 inhibition treatment (i.e., pegcetacoplan, SYFOVRE™, Apellis) was approved in February 2023 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GA. Intravitreal injection of pegcetacoplan proved to significantly slower GA progression as compared with sham treatment in AMD-associated GA [12]. Notably, pegcetacoplan-treated eyes were characterized by a significantly slower GA lesion progression toward the fovea [13]. Assuming the expected growing use of this drug and other complement inhibitors in the upcoming years, it would appear to be of great importance to detect risk factors for the foveal involvement in extrafoveal GA eyes at baseline. Importantly, the identification of these risk factors may broaden our knowledge regarding the AMD-associated GA pathogenesis.

Structural optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an essential diagnostic tool for the evaluation of individuals with GA as it provides anatomic details regarding the neuroretina and RPE. Previous reports have identified several OCT biomarkers associated with GA occurrence and progression. These biomarkers include the size, volume, and subtype of drusen, the presence of hyper-reflective foci, thin double-layer sign (DLS), and subretinal drusenoid deposits (i.e., also known as reticular pseudodrusen—RPD), thinning of the outer retina, photoreceptor degradation, choroidal thinning, and CC loss [4, 14–20].

In this longitudinal study over 2 years of follow-up, we explored the associations of structural OCT findings to progression to foveal atrophy in a cohort of eyes with extrafoveal GA at inclusion (study baseline).

Methods

The San Raffaele Ethics Committee approved this retrospective cohort study. This study adhered to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was gained from all individuals included in the study.

Subjects

Patients with extrafoveal GA secondary to AMD [21] were identified from the medical records at San Raffaele Scientific Institute. The diagnosis of GA was established through a comprehensive approach involving fundus ophthalmoscopy, blue fundus autofluorescence (BAF), and OCT. Specifically, GA was identified when a hypopigmented area with visible choroidal vessels on fundus ophthalmoscopy corresponded to a hypoautofluorescent area on BAF, accompanied by corresponding RPE atrophy visualized on structural OCT. A diagnosis of extrafoveal GA was established when atrophy was not detected in the foveal region, as determined through multimodal imaging. At baseline visit, the following exclusion criteria were considered for the study eye: (i) prior history or evidence of macular neovascularization (MNV), including non-exudative cases; (ii) history of previous ocular surgeries including anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections; and (iii) history or evidence of other retinal and optic nerve disorders. To be included, subjects were also required to not develop MNV throughout the 2-year follow-up and have at least two yearly retinal visits including structural OCT, BAF, and infrared reflectance (IR) images covering a study period of 2 years (24 months) after the baseline visit. The population fulfilling these criteria was the starting cohort for this analysis (n = 412 GA patients in our database).

Structural OCT, BAF, and IR imaging was performed with the Heidelberg Spectralis HRA + OCT device (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The spectral domain OCT imaging session included 19 horizontal B-scans covering approximately a 5.5 × 4.5-mm area centered on the fovea and 6 radial linear B-scans captured with enhanced depth imaging (EDI) and centered on the fovea. Each B-scan was composed by 25 averaged OCT images. A minimum signal strength of 25 was required to the OCT images to be included, as recommended by the manufacturer [22].

OCT grading

Baseline and follow-up structural OCT images were first reviewed for eligibility by an experienced and certified grader (EB).

Therefore, at baseline, eligible eyes (n = 45) were independently graded for qualitative features and quantitative metrics by two graders (CB and AB) who were masked as to the final eyes’ outcomes (i.e., see below for details). Of note, the baseline visit was the first visit with evidence of extrafoveal GA.

In details, OCT images at baseline were graded for qualitative features that were previously demonstrated to be associated with GA occurrence and progression:

Pigment epithelium detachment in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid central circle (dimensions: 1 mm diameter): OCT images were scrutinized for the presence of flat pigment epithelium detachments (PEDs) with a thin DLS. The DLS was classified as thin when a single zone of low to medium reflectivity was evident between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane [20].

Reticular pseudodrusen: the presence or absence of RPD was assessed on the basis of multimodal imaging analyses, as previously described in details [23].

Focality: the graders graded GA as unifocal vs. multifocal using structural OCT, IR, and BAF images.

Disagreements between graders in the qualitative grading were resolved by further debate and open adjudication to yield a single reading. The final decision was made by an experienced and certified grader (EB) whether the two graders were not able to reach a single consensus result.

At baseline, OCT images were also employed to obtain quantitative measurements.

The Spectralis built-in software was used to measure the outer retinal layer (ORL) thickness. As in a previous study on GA, the ORL extended from the upper boundary of the outer plexiform layer (OPL) to the inner boundary of the RPE [19]. Therefore, the ORL was a combination of OPL and outer nuclear layer (ONL). OCT metrics were obtained across each of the ETDRS subfields: the central foveal circle with a 1 mm diameter, the inner circle subfield (dimensions: inner and outer radii of 0.5 and 1.5 mm), and the outer circle subfield (dimensions: inner and outer radii of 1.5 and 3.0 mm). Before computing the thickness and volume values, all B-scans were scrutinized by graders and segmentations were manually corrected. The final segmentation was also reviewed and eventually corrected by an experienced and certified grader (EB).

Using the Spectralis built-in software, the RPE to Bruch’s membrane (BM) volume was also obtained by applying inner and outer segmentation boundaries at the RPE and RPE fit (estimated Bruch’s membrane position) levels, as previously showed [19, 20]. Of note, the RPE-RPE fit volume was also termed the drusen volume in previous studies [20]. Assuming that this space may contain both drusen and flat PEDs with a thin DLS (i.e., in absence of other types of PEDs), we felt the term RPE to BM volume was a more preferred term to indicate this metric [19].

Minimum distance from the central foveal circle: using the built-in software caliper, the graders measured the distance to the nearest GA border using OCT and IR images.

Untransformed GA lesion size area: the graders measured the GA size within the inner and outer circle subfields on IR images using the built-in software caliper.

Finally, the set of follow-up visits was graded for GA progression toward the fovea, as follows:

Foveal central area involvement was graded as present if GA involved the ETDRS grid central circle (dimensions: 1 mm diameter) [8]. We felt the latter assessment might be clinically relevant as the decrease of the spared area in the central 1 mm is associated with a severe decline in visual acuity in GA patients [8]. This grading was made by employing multimodal imaging (i.e., structural OCT, IR, and BAF). In detail, for IR and BAF images, the ETDRS grid was centered on the fovea, identified through structural OCT. Subsequently, the GA was graded to involve the fovea through multimodal imaging. In details, this was determined by the presence of a hypoautofluorescent area affecting the central circle, which corresponded to a hyperreflective area on IR imaging and was identified as region of RPE atrophy using structural OCT.

Foveal central point involvement was graded as being present whether the foveal center point on the cross-sectional OCT was involved by GA [24]. Multimodal imaging (i.e., structural OCT, IR, and BAF) was employed to assess the location of the foveal center point in correlation with the GA border.

Study outcomes and statistical analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 23.0.0.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

To detect departures from normal distribution, a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was performed for all quantitative variables. Mean, standard deviation (SD), and interquartile range (IQR) were computed for all quantitative variables. Student’s t-test and non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test were conducted to investigate differences in continuous variables between groups at baseline. Qualitative variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was computed to compare visual acuity between baseline and follow-up visits.

Logistic regression analysis for each variable was first performed to determine whether each baseline feature was associated with the development of atrophy in the foveal central circle (dependent variable) at the 24-month follow-up visit. Those features with a p value inferior to 0.1 were successively included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis that was carried out to identify independent significant predictors and compute odds ratios (ORs) for the risk of the development of atrophy. Similarly, univariable and multivariable regression analyses were also computed considering the development of atrophy in the foveal central point at the 24-month follow-up visit as the dependent variable.

The agreement between graders in the qualitative grading was investigated using the unweighted k statistic test.

Results

A total of 45 eyes from 45 patients (29 females) with extrafoveal GA secondary to non-neovascular AMD were finally included in our analysis. Mean ± SD age was 75.9 ± 7.8 years. Mean ± SD number of follow-up visits throughout the 24 months following the baseline assessment was 5.4 ± 1.4.

Among the cohort of 45 eyes with extrafoveal GA at baseline, 26 eyes (57.8%) developed atrophy in the foveal central circle by 24 months, while 11 eyes (24.4%) developed atrophy in the foveal central point within the follow-up period.

Overall, the BCVA was 0.19 ± 0.18 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/32) at baseline and 0.31 ± 0.36 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/40) at the 24-month follow-up visit (p < 0.0001). The final BCVA was 0.21 ± 0.12 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/32) and 0.41 ± 0.40 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/50) in eyes without and with atrophy in the foveal central circle at the last follow-up visit (p = 0.045). Similarly, the final BCVA was 0.22 ± 0.18 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/32) and 0.60 ± 0.18 LogMAR (Snellen VA of ~ 20/80) in eyes without and with atrophy in the foveal central point at the last follow-up visit (p = 0.001).

Baseline risk factors for development of foveal atrophy

The quantitative values and prevalence of qualitative biomarkers of interest among these 45 eyes at baseline are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline variables

| GA lesion size area—inner ring subfield (mm2) | 0.90 ± 1.24 (0.20–1.14) |

| GA lesion size area—outer ring subfield (mm2) | 0.58 ± 1.60 (0.00–0.07) |

| Minimum distance from the foveal central circle (µm) | 280.7 ± 232.8 (114.7–337.7) |

| Focality (multifocality), n (%) | 20 (44.4%) |

| Reticular pseudodrusen, n (%) | 24 (53.3%) |

| Foveal thin DLS, n (%) | 11 (24.4%) |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—foveal central circle (µm) | 107.0 ± 15.8 (95.5–123.7) |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—inner ring subfield (µm) | 76.9 ± 15.3 (66.6–88.8) |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—outer ring subfield (µm) | 68.5 ± 13.6 (59.9–79.1) |

| RPE to BM volume—foveal central circle (mm2) | 0.02 ± 0.01 (0.01–0.02) |

Quantitative values are expressed in mean ± SD (IQR). Qualitative values are reported as number of eyes (percentage)

GA, geographic atrophy; n, number of eyes; DLS, double layer sign; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; BM, Bruch’s membrane

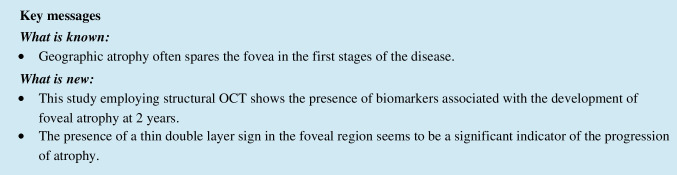

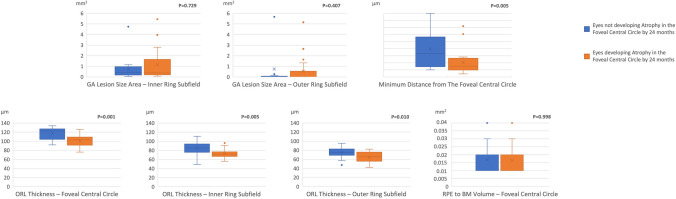

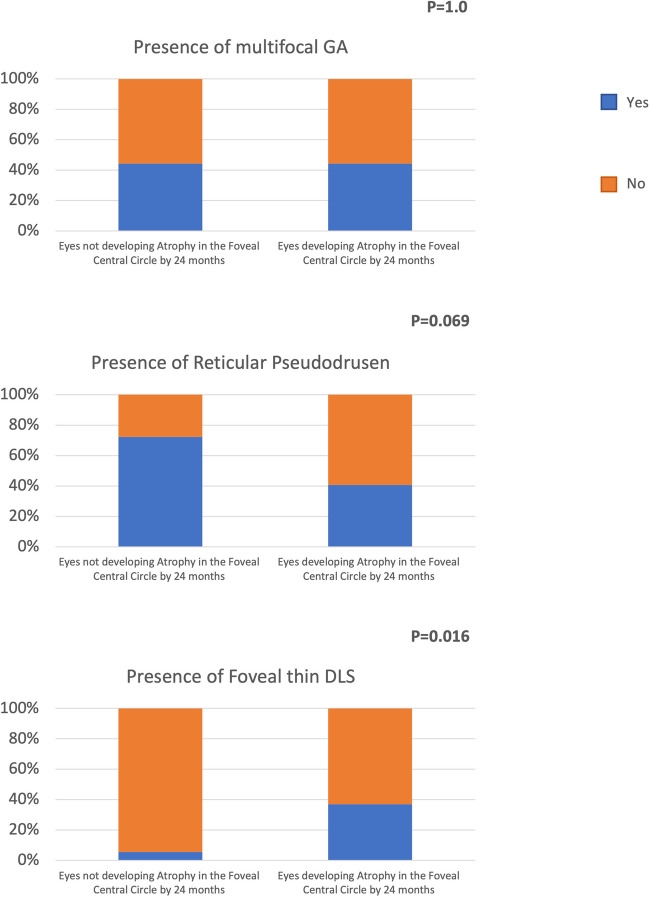

At the baseline visit, the minimum distance from the foveal central circle and outer retinal thicknesses in all the analyzed subfields were lower in eyes developing atrophy in the foveal central circle within 24 months (Fig. 1). Figure 2 shows relative frequencies of each baseline imaging finding in the study cohort. The presence of foveal thin DLS was more prevalent in eyes developing atrophy in the foveal central circle within 24 months (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Box and whisker plots showing analyzed metrics in GA patients. Each box displays mean (cross within the box), median (central horizontal line), and interquartile range (horizontal extremes of the box) values for each metric. The ends of the whiskers illustrate the minimum and maximum values. Outliers are visualized as dots not included in whiskers. Each graph reports comparisons for a specific metric and p values for each comparison are reported

Fig. 2.

Grouped column chart showing the relative frequencies of qualitative findings in the study cohort. Each chart shows the relative frequencies of eyes graded with a specific finding. The relative frequencies are given as a percentage of patients with a specific qualitative finding in a distinct group (GA patients developing vs. not developing atrophy in the foveal central circle). On the X axis, columns are grouped on the basis of the development of atrophy in the foveal central circle. p values for each comparison are reported in the figure

Fig. 3.

Representative optical coherence tomography (OCT) B-scan of a patient with extrafoveal GA. OCT B-scan (left) showing the presence of a thin DLS (orange dashed rectangle) and SDDs (red dashed rectangle). A magnified visualization of these regions of interest is reported on the right

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the results of the logistic regression analyses performed on the baseline imaging findings. Significant independent predictive features for the development of atrophy in the foveal central circle included the following: foveal outer retinal thickness (OR, 0.867; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.772–0.972; p = 0.015), minimum distance from the foveal central circle (OR, 0.992; 95% CI, 0.986–0.999; p = 0.022), and foveal thin DLS (OR, 0.044; 95% CI, 0.002–0.812; p = 0.036) (Table 2). The only independent predictive feature for the development of atrophy in the foveal central point was the presence of foveal thin DLS (OR, 0.138; 95% CI, 0.027–0.697; p = 0.017) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline risk factors for the development of atrophy in the foveal central circle by 24 months

| Baseline variables | Univariate analysis (logistic regression) | Multiple logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratios | 95% CI | p value | Odds ratios | 95% CI | p value | |

| GA lesion size area—inner ring subfield | 1.230 | 0.713–2.121 | 0.457 | – | – | – |

| GA lesion size area—outer ring subfield | 0.891 | 0.610–1.301 | 0.550 | – | – | – |

| Minimum distance from the foveal central circle | 0.996 | 0.992–0.999 | 0.015 | 0.992 | 0.986–0.999 | 0.022 |

| Focality (multifocality) | 1.071 | 0.320–3.585 | 0.911 | – | – | – |

| Reticular pseudodrusen | 3.545 | 0.974–12.905 | 0.055 | 1.415 | 0.165–12.106 | 0.751 |

| Foveal thin DLS | 0.094 | 0.011–0.821 | 0.032 | 0.044 | 0.002–0.812 | 0.036 |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—foveal central circle | 0.910 | 0.859–0.965 | 0.002 | 0.867 | 0.772–0.972 | 0.015 |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—inner ring subfield | 0.930 | 0.880–0.982 | 0.009 | 1.098 | 0.940–1.283 | 0.238 |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—outer ring subfield | 0.930 | 0.877–0.896 | 0.016 | 0.867 | 0.716–1.049 | 0.142 |

| RPE to BM volume—foveal central circle | 0.261 | 0.000–1.338E + 26 | 0.966 | – | – | – |

CI, confidence interval; GA, geographic atrophy; DLS, double layer sign; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; BM, Bruch’s membrane

Table 3.

Baseline risk factors for the development of atrophy in the foveal central point by 24 months

| Baseline variables | Univariate analysis (logistic regression) | Multiple logistic regression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratios | 95% CI | p value | Odds ratios | 95% CI | p value | |

| GA lesion size area—inner ring subfield | 1.214 | 0.731–2.018 | 0.454 | – | – | – |

| GA lesion size area—outer ring subfield | 1.140 | 0.773–1.681 | 0.509 | – | – | – |

| Minimum distance from the foveal central circle | 0.999 | 0.996–1.003 | 0.692 | – | – | – |

| Focality (multifocality) | 0.607 | 0.149–2.475 | 0.487 | – | – | – |

| Reticular pseudodrusen | 2.692 | 0.655–11.061 | 0.170 | – | – | – |

| Foveal thin DLS | 0.149 | 0.033–0.681 | 0.014 | 0.138 | 0.027–0.697 | 0.017 |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—foveal central circle | 0.958 | 0.913–1.005 | 0.080 | 0.954 | 0.905–1.007 | 0.087 |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—inner ring subfield | 0.984 | 0.941–1.030 | 0.501 | – | – | – |

| Outer retinal layer thickness—outer ring subfield | 0.985 | 0.937–1.036 | 0.557 | – | – | – |

| RPE to BM volume—foveal central circle | 10,827.045 | 0.000–4.154E + 33 | 0.789 | – | – | – |

CI, confidence interval; GA, geographic atrophy; DLS, double layer sign; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; BM, Bruch’s membrane

Intergrader repeatability

The unweighted k values were 0.80 (42/45) for presence of foveal thin DLS, 1.0 (45/45) for presence of reticular pseudodrusen, and 1.0 (45/45) for GA focality.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated baseline predictors of foveal involvement in subjects with extrafoveal GA and non-neovascular AMD at baseline. Overall, we demonstrated that several imaging risk factors are associated with a higher risk for progression from extrafoveal GA to foveal involvement after 2 years from the baseline, including lower foveal ORL thickness and minimum distance from the foveal central circle, and presence of foveal thin DLS.

The retina surrounding the atrophic area is known to be more prone to develop atrophy over time [25]. Therefore, the findings in our study of an increased risk to develop atrophy in the foveal central circle in eyes with a shorter minimum distance from the foveal central circle at baseline may indicate that early changes in the retina surrounding the atrophic lesion may be involving the fovea, this eventually leading to foveal atrophy over time. Baseline GA size and lesion number were not correlated with GA growth rate [26]. Consistently, our results did not show any association between foveal involvement after 2 years and these two characteristics at baseline.

In order to quantify the damage of the outer retina, we also performed a topographic quantitative analysis of the ORL thickness. In our analysis employing multivariate model, higher foveal ORL thickness at baseline was independently associated with a lower risk of foveal central circle within 2 years. In a previous important study, Zhang and colleagues [19] investigated whether the ORL thickness around GA may predict the annual enlargement rate of GA. They demonstrated that this thickness is inversely associated with annual GA growth. Therefore, our results appear to further confirm that the thickness of the outer retina in macular regions spared by GA is a consistent risk factor for atrophy involvement over time.

In our analysis, the presence of a foveal thin DLS was an independent baseline risk factor for GA involvement of the foveal central circle within 2 years. In AMD, it has been hypothesized that this OCT finding may correspond to regions of thick basal laminar deposit (BLamD) without vessels [19, 20, 27]. As proposed in previous studies [19, 20, 27], our finding that presence of a thin DLS is a risk factor for foveal atrophy within 2 years may be related to accumulation of BLamD obstructing perfusion of the RPE from the CC, which may further exacerbate the RPE ischemia and dysfunction. It is important to note that the presence of a foveal thin DLS was the only independent predictive feature for the development of atrophy in the foveal central point. In our study cohort, when the foveal central point becomes involved, a dramatic loss in vision occurs. Therefore, the definition of risk factors for the foveal central point atrophy may be clinically relevant. Since this was the only independent risk factor for the development of atrophy in the foveal central point, we may speculate that the presumed increase in basal laminar deposits in the foveal region may indicate a more consistent risk factor for the development of atrophy in this region.

Conversely, a thick DLS (i.e., flat PED enclosing more than 1 layer of low to medium reflectivity between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane) appears to be associated with presence of neovessels [20]. Of note, non-exudative neovessels in the AMD setting appear to provide support to the RPE and outer retina, this eventually leading to a protective effect against atrophy [28]. Assuming that non-exudative neovessels appear to be a well-established protective factor against RPE atrophy, though their presence may be relatively unusual, we did not include cases with this finding.

Reticular pseudodrusen (i.e., subretinal drusenoid deposits above the RPE on OCT and histopathology) may be commonly found in AMD eyes. Although RPD and drusen may coexist, these two abnormalities have significant differences in terms of histopathology and anatomy [29]. Importantly, while drusen are mainly confined to the foveal and parafoveal regions [30], RPD preferentially localize in the perifoveal macula and/or near-mid retinal periphery [31]. In our study cohort of eyes with extrafoveal GA at baseline, the presence of RPD was not associated with a greater risk for progression to foveal involvement within 2 years. Although the presence of RPD is a recognized risk factor for GA development and progression [32], we may speculate that this finding is not associated with a greater risk of foveal involvement as GA mainly expand into areas with RPD when present and RPD typically spare the foveal region [15]. It should be acknowledged, however, that the presence of RPD was not a protective factor for foveal atrophy in our study cohort. Future larger studies may elucidate whether the presence and distribution of RPD in extrafoveal GA eyes may impact on the progression of atrophy toward the fovea.

Several previous structural OCT studies have demonstrated that RPE to BM volume is a relevant risk factor for development and progression of GA in AMD patients [19, 20, 27, 33]. In a recent study, Chu et al. [14] performed a retrospective study with 38 eyes of 27 patients characterized by areas of GA. The authors demonstrated that RPE–BM distance around the GA area correlate with the annual enlargement of GA. As asserted above, a greater amount of material between the RPE and BM might exacerbate the outer retinal ischemia [19, 20, 27]. Alternatively, voluminous drusen may be more prone to collapse with resulting atrophy [34]. However, changes in drusen volume are dynamic and not progressive throughout the course of the disease. Therefore, drusen volume was suggested to not be a stable or consistent marker [20]. Consistently, in the present study, the presence of a higher central RPE to BM volume was not associated with a greater risk for progression to foveal involvement.

The main limitation of our study was that our study cohort was not part of a large multicenter trial and included subjects did not undertake regular follow-up visits with consistent intervals. Another important limitation is that segmentation errors occur frequently in AMD eyes, resulting in erroneous measurements [35]. In order to moderate the latter limitation, OCT B-scans were scrutinized for segmentation errors that were manually corrected by two graders. Moreover, the manually adjusted boundaries were successively revised by an experienced and certified grader (EB). Another limitation is that OCT angiography was not available for this analysis and we were not able to assess whether the CC perfusion is an additional risk factor for the 2-year foveal involvement. Future OCT angiography studies may clarify the latter aspect.

In conclusion, this study identifies OCT risk factors for 2-year foveal atrophy in eyes with untreated extrafoveal GA at baseline. Future larger studies are needed to confirm our findings. Assuming that pegcetacoplan-treated eyes are characterized by a significantly slower GA lesion progression toward the fovea [13], the identification of risk factors for progression toward the fovea is clinically relevant.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the San Raffaele University and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferris FL, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, et al. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Klein BEK, Linton KLP. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:S122–S132. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudnicka AR, Kapetanakis VV, Jarrar Z, et al. Incidence of late-stage age-related macular degeneration in American Whites: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:85–93.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dolz-Marco R, Balaratnasingam C, Messinger JD, et al. The border of macular atrophy in age-related macular degeneration: a clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;193:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleckenstein M, Mitchell P, Freund KB, et al. The progression of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2018;125:369–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL (1996) Photoreceptor loss in age-related macular degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 37(7):1236–1249 [PubMed]

- 7.Pilotto E, Guidolin F, Convento E, et al. Fundus autofluorescence and microperimetry in progressing geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:622 LP–626. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayegh RG, Sacu S, Dunavölgyi R, et al. Geographic atrophy and foveal-sparing changes related to visual acuity in patients with dry age-related macular degeneration over time. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;179:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindblad AS, Lloyd PC, Clemons TE, et al. Change in area of geographic atrophy in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report number 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1168–1174. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grassmann F, Harsch S, Brandl C, et al. Assessment of novel genome-wide significant gene loci and lesion growth in geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:867–876. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabral de Guimaraes TA, Daich Varela M, Georgiou M, Michaelides M. Treatments for dry age-related macular degeneration: therapeutic avenues, clinical trials and future directions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2022;106:297 LP–304. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-318452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao DS, Grossi FV, El Mehdi D, et al. Complement C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized phase 2 trial. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogl W-D, Riedl S, Mai J, et al. Predicting topographic disease progression and treatment response of pegcetacoplan in geographic atrophy quantified by deep learning. Ophthalmol Retin. 2023;7:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2022.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu Z, Shi Y, Zhou X, et al. Optical coherence tomography measurements of the retinal pigment epithelium to bruch membrane thickness around geographic atrophy correlate with growth. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;236:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marsiglia M, Boddu S, Bearelly S, et al. Association between geographic atrophy progression and reticular pseudodrusen in eyes with dry age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:7362–7369. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niu S, de Sisternes L, Chen Q, et al. Fully automated prediction of geographic atrophy growth using quantitative spectral-domain optical coherence tomography biomarkers. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1737–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veerappan M, El-Hage-Sleiman AKM, Tai V, et al. Optical coherence tomography reflective drusen substructures predict progression to geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi Y, Zhang Q, Zhou H, et al. Correlations between choriocapillaris and choroidal measurements and the growth of geographic atrophy using swept source OCT imaging. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;224:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Q, Shi Y, Shen M, et al. Does the outer retinal thickness around geographic atrophy represent another clinical biomarker for predicting growth? Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;244:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirabayashi K, Yu HJ, Wakatsuki Y, et al. OCT risk factors for development of atrophy in eyes with intermediate age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology Retina. 2023;7:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2022.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Sahel J-A, Danis R, et al. Natural history of geographic atrophy progression secondary to age-related macular degeneration (Geographic Atrophy Progression Study) Ophthalmology. 2016;123:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y, Gangaputra S, Lee KE, et al. Signal quality assessment of retinal optical coherence tomography images. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2133–2141. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borrelli E, Costanzo E, Parravano M, et al. Impact of bleaching on photoreceptors in different intermediate AMD phenotypes. Trans Vis Sci Technol. 2019;8:5. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.6.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heier JS, Pieramici D, Chakravarthy U, et al. Visual function decline resulting from geographic atrophy: results from the Chroma and Spectri phase 3 trials. Ophthalmol Retin. 2020;4:673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2020.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nassisi M, Baghdasaryan E, Borrelli E et al (2019) Choriocapillaris flow impairment surrounding geographic atrophy correlates with disease progression. PloS One 14(2):e0212563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Holz FG, Sadda SR, Busbee B, et al. Efficacy and safety of lampalizumab for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: Chroma and Spectri phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:666–677. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sura AA, Chen L, Messinger JD et al (2020) Measuring the contributions of basal laminar deposit and bruch's membrane in age-related macular degeneration. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61(13):19. 10.1167/iovs.61.13.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fukuyama H, Huang BB, BouGhanem G, Fawzi AA. The fovea-protective impact of double-layer sign in eyes with foveal-sparing geographic atrophy and age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63:4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.63.11.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curcio CA, Presley JB, Millican CL, Medeiros NE. Basal deposits and drusen in eyes with age-related maculopathy: evidence for solid lipid particles. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:761–775. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curcio CA. Photoreceptor topography in ageing and age-related maculopathy. Eye. 2001;15:376–383. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold JJ, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Reticular pseudodrusen: a risk factor in age-related maculopathy. Retina. 1995;15:183–191. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199515030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finger RP, Wu Z, Luu CD, et al. Reticular pseudodrusen: a risk factor for geographic atrophy in fellow eyes of individuals with unilateral choroidal neovascularization. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1252–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nassisi M, Lei J, Abdelfattah NS, et al. OCT risk factors for development of late age-related macular degeneration in the fellow eyes of patients enrolled in the HARBOR Study. Ophthalmology. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdelfattah NS, Zhang H, Boyer DS, et al. Drusen volume as a predictor of disease progression in patients with late age-related macular degeneration in the fellow eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1839–1846. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang YH, Kim MK, Kim DW. Segmentation errors in macular ganglion cell analysis as determined by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:950–958. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]