Abstract

Background

Health consumers increasingly want access to accurate, evidence‐based information about their medications. Currently, education about medications (that is, information that is designed to achieve health or illness related learning) is provided predominantly via spoken communication between the health provider and consumer, sometimes supplemented with written materials. There is evidence, however, that current educational methods are not meeting consumer needs. Multimedia educational programs offer many potential advantages over traditional forms of education delivery.

Objectives

To assess the effects of multimedia patient education interventions about prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications in people of all ages, including children and carers.

Search methods

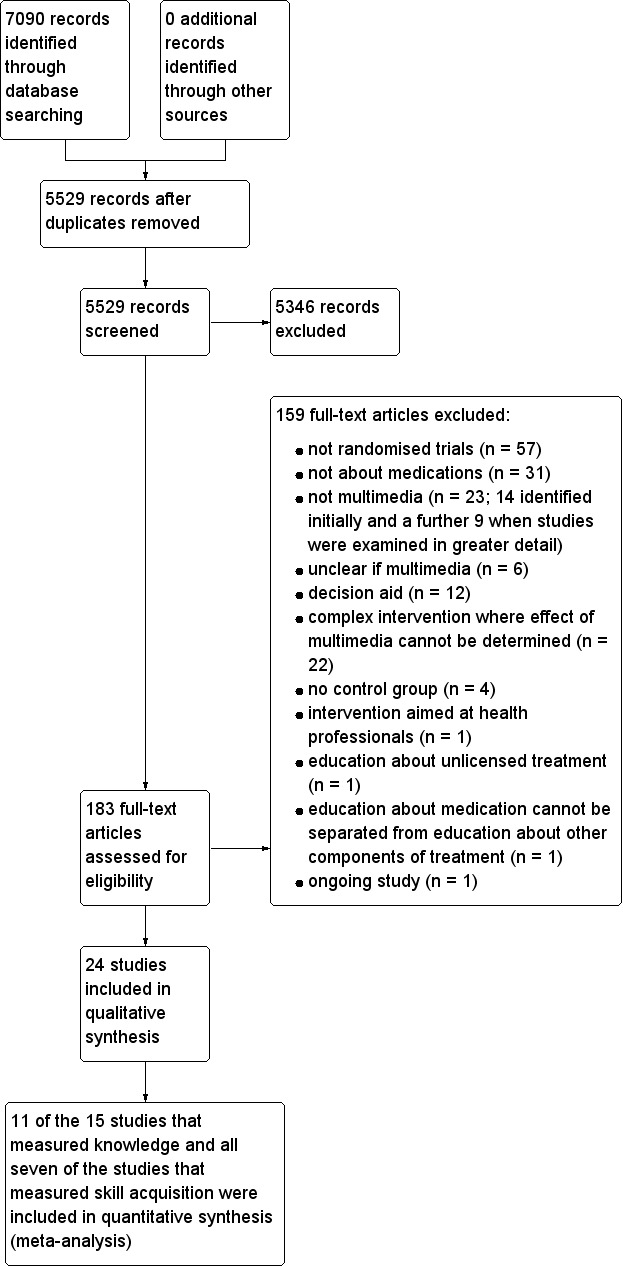

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2011, Issue 6), MEDLINE (1950 to June 2011), EMBASE (1974 to June 2011), CINAHL (1982 to June 2011), PsycINFO (1967 to June 2011), ERIC (1966 to June 2011), ProQuest Dissertation & Theses Database (to June 2011) and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs of multimedia‐based patient education about prescribed or over‐the‐counter medications in people of all ages, including children and carers, if the intervention had been targeted for their use.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. Where possible, we contacted study authors to obtain missing information.

Main results

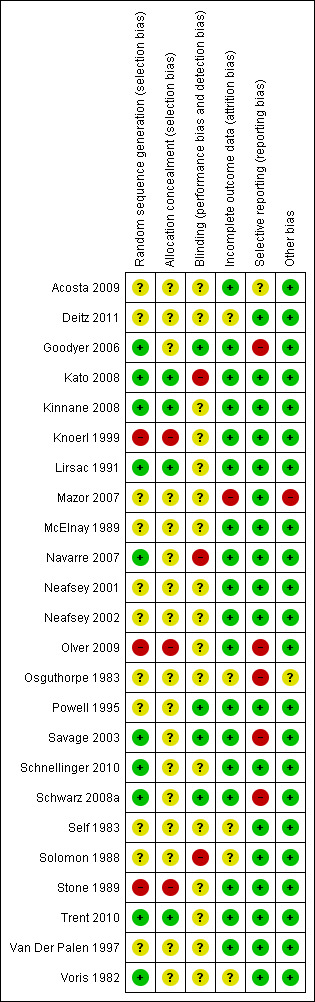

We identified 24 studies that enrolled a total of 8112 participants. However, there was significant heterogeneity in the comparators used and the outcomes measured, which limited the ability to pool data. Many of the studies did not report sufficient information in their methods to allow judgment of their risk of bias. From the information that was reported, three of the studies had a high risk of selection bias and one was at high risk of bias due to lack of blinding of the outcome assessors. None of the included studies reported the minimum clinically important difference for the outcomes that were measured. We have therefore reported results from the studies but have been unable to interpret whether differences were of clinical importance.

The main findings of the review are as follows.

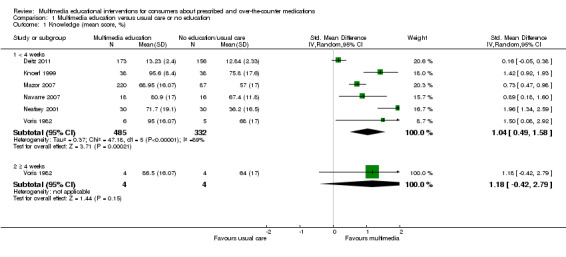

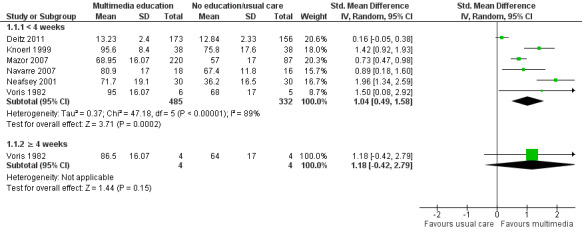

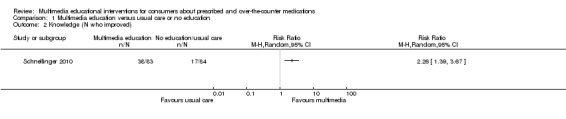

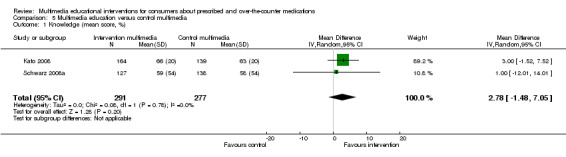

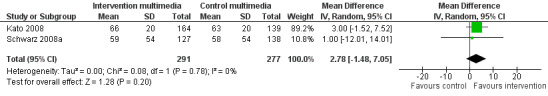

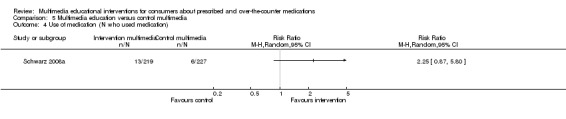

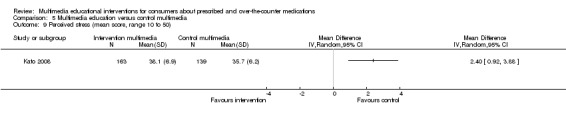

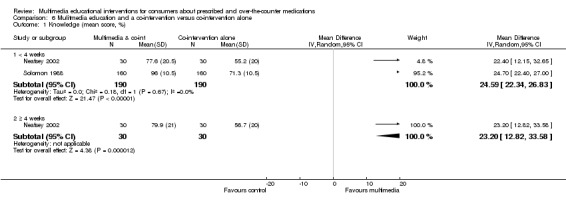

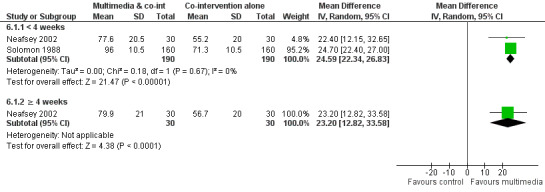

Knowledge: There is low quality evidence that multimedia education was more effective than usual care (non‐standardised education provided as part of usual clinical care) or no education (standardised mean difference (SMD) 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49 to1.58, six studies with 817 participants). There was considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 89%), however, all but one of the studies favoured the multimedia group. There is moderate quality evidence that multimedia education was not more effective at improving knowledge than control multimedia interventions (i.e. multimedia programs that do not provide information about the medication) (mean difference (MD) of knowledge scores 2.78%, 95% CI ‐1.48 to 7.0, two studies with 568 participants). There is moderate quality evidence that multimedia education was more effective when added to a co‐intervention (written information or brief standardised instructions provided by a health professional) compared with the co‐intervention alone (MD of knowledge scores 24.59%, 95% CI 22.34 to 26.83, two studies with 381 participants).

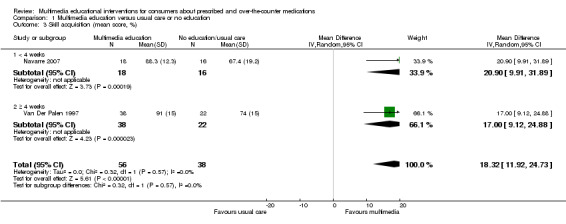

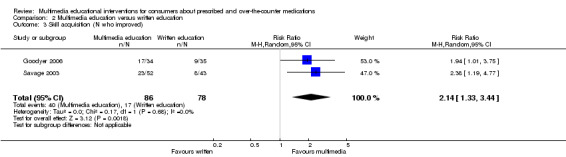

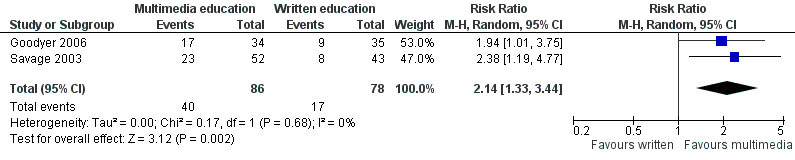

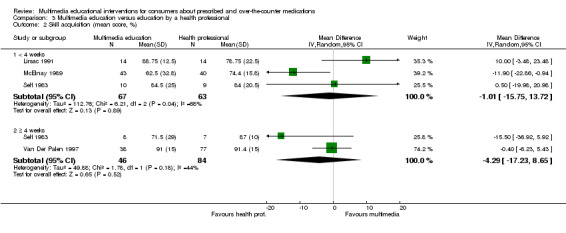

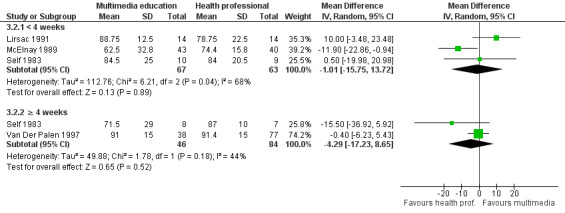

Skill acquisition: There is moderate quality evidence that multimedia education was more effective than usual care or no education (MD of inhaler technique score 18.32%, 95% CI 11.92 to 24.73, two studies with 94 participants) and written education (risk ratio (RR) of improved inhaler technique 2.14, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.44, two studies with 164 participants). There is very low quality evidence that multimedia education was equally effective as education by a health professional (MD of inhaler technique score ‐1.01%, 95% CI ‐15.75 to 13.72, three studies with 130 participants).

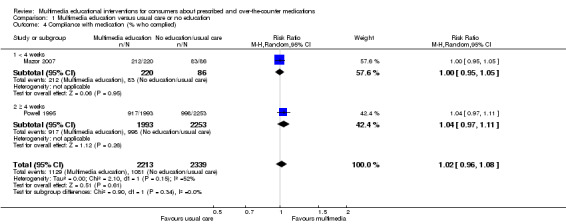

Compliance with medications: There is moderate quality evidence that there was no difference between multimedia education and usual care or no education (RR of complying 1.02, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.08, two studies with 4552 participants).

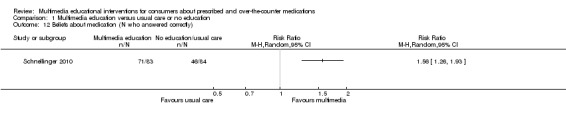

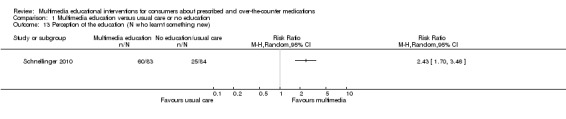

We could not determine the effect of multimedia education on other outcomes, including patient satisfaction, self‐efficacy and health outcomes, due to an inadequate number of studies from which to draw conclusions.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides evidence that multimedia education about medications is more effective than usual care (non‐standardised education provided by health professionals as part of usual clinical care) or no education, in improving both knowledge and skill acquisition. It also suggests that multimedia education is at least equivalent to other forms of education, including written education and education provided by a health professional. However, this finding is based on often low quality evidence from a small number of trials. Multimedia education about medications could therefore be considered as an adjunct to usual care but there is inadequate evidence to recommend it as a replacement for written education or education by a health professional. Multimedia education may be considered as an alternative to education provided by a health professional, particularly in settings where provision of detailed education by a health professional is not feasible. More studies evaluating multimedia educational interventions are required in order to increase confidence in the estimate of effect of the intervention.

Conclusions regarding the effect of multimedia education were limited by the lack of information provided by study authors about the educational interventions, and variability in their content and quality. Studies testing educational interventions should provide detailed information about the interventions and comparators. Research is required to establish a framework that is specific for the evaluation of the quality of multimedia educational programs. Conclusions were also limited by the heterogeneity in the outcomes reported and the instruments used to measure them. Research is required to identify a core set of outcomes which should be measured when evaluating patient educational interventions. Future research should use consistent, reliable and validated outcome measures so that comparisons can be made between studies.

Keywords: Humans; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Multimedia; Medication Adherence; Nonprescription Drugs; Nonprescription Drugs/therapeutic use; Patient Education as Topic; Patient Education as Topic/methods; Patient Education as Topic/standards; Prescription Drugs; Prescription Drugs/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Multimedia programs for educating patients about medications

Consumers need detailed information about their medications to enable them to use their medications safely and effectively. For information to be useful it needs to be presented in a format that can be easily understood by consumers. There is evidence that methods such as spoken communication between the health provider and consumer and written materials are not meeting consumers’ needs. Multimedia education programs use more than one format to provide information. This could include using written words, diagrams and pictures with the use of audio, animation or video. They can be provided using different technologies, such as DVD and CD‐ROM, or can be accessed over the Internet.

This review presents the evidence from 24 studies, involving 8112 participants, of multimedia education programs about medications.

We found that multimedia education programs about medications are superior to no education or education provided as part of usual clinical care in improving patient knowledge. There was wide variability in the results from the six studies that compared multimedia education to usual care or no education. However, all but one of the six studies favoured multimedia education. We also found that multimedia education is superior to usual care or no education in improving skill levels. The review also suggested that multimedia was at least as effective as other forms of education, including written education or brief education from a health provider. However, these findings were based on a small number of studies, many of which were of low quality. Multimedia education did not improve compliance with medications (i.e. the degree to which a patient correctly follows advice about his or her medication) compared with usual care or no education. We could not determine the effect of multimedia education on other outcomes, such as patient satisfaction, self‐efficacy (confidence in their ability to perform health‐related tasks) and health outcomes.

The review findings therefore suggests that multimedia education programs about medications could be used alongside usual care provided by health providers. There is not enough evidence to recommend it as a replacement for written education or education by a health professional. Multimedia education could be used instead of detailed education given by a health provider when it is not possible or practical for health professionals to provide this service.

This review found that there were differences between the types of education provided to the control groups and what results were measured. This limited the ability to summarise results across studies, so most of the conclusions of this review were based on results from a small number of studies. More studies of multimedia educational programs are needed to make the results of this review more reliable.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings: multimedia education compared with no education or usual care.

| Multimedia education compared with no education or usual care for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education Comparison: no education or usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| no education or usual care | multimedia education | |||||

|

Knowledge (< 4 weeks)

Mean number of correct responses (higher score indicates higher knowledge) Follow‐up: 0 to 3 weeks |

The mean knowledge (< 4 weeks) in the intervention groups was 1.04 higher (0.49 to 1.58 higher) | 817 (6 studies) | ++OO lowa,b | Standardised score used as one study (Deitz 2011) did not provide a denominator and therefore could not be converted to the same scale as the other studies. A standard deviation of 1.04 represents a large difference between groups. 1 further study of 167 patients measured the number whose knowledge score improved and found that this was 458 versus 202 per 1000 in the intervention and control groups respectively (RR 2.26, 95% CI 1.39 to 3.67). The quality of the evidence was lowa,c. 1 study with 8 patients measured mean knowledge (%) at 4 weeks or more and found it was 22.5 higher (0.42 lower to 45.42 higher) in the intervention group. The quality of the evidence was very lowa,c,d. |

||

|

Skill acquisition

Mean inhaler technique score (%), higher score indicates better technique. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 0 to 9 months |

The mean skill acquisition in the control groups was 71.22%e | The mean skill acquisition in the intervention groups was 18.32 higher (11.92 to 24.73 higher) | 94 (2 studies) | +++O moderatea | ||

|

Compliance with medication

(different measures used by the studies: patient self‐report of compliance and prescription refill data). Follow‐up: 3 to 39 weeks |

Low risk populationf | RR 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) | 4552 (2 studies) | +++O moderatea | ||

| 443 per 1000 | 452 per 1000 (425 to 478) | |||||

| Medium risk populationf | ||||||

| 704 per 1000 | 718 per 1000 (676 to 760) | |||||

| High risk populationf | ||||||

| 965 per 1000 | 984 per 1000 (926 to 1000) | |||||

|

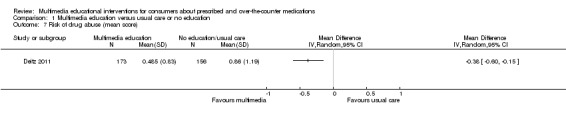

Health outcomes: Drug misuse and dependence CAGE screening tool. Scale from 0 to 4. Higher score indicates greater probability of drug misuse or dependence |

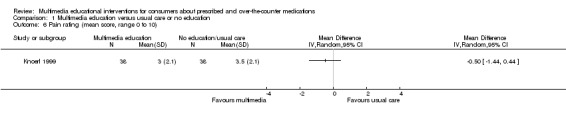

The mean CAGE score in the control group was 0.86 | The mean CAGE score in the intervention group was 0.38 lower (0.60 lower to 0.15 lower) | 329 (1 study) |

++OO lowa,c | 1 further study with 43 participants measure pain on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible pain) and found that pain in the intervention group was 0.5 lower (1.44 lower to 0.44 higher). However, the quality of evidence was very lowc,g. | |

| Medication side effects ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | One study measured medication side effects but did not report results in a form that could be extracted for meta‐analysis. The authors reported no statistically‐significant difference in the incidence of side effects between the two groups. |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured quality of life. |

|

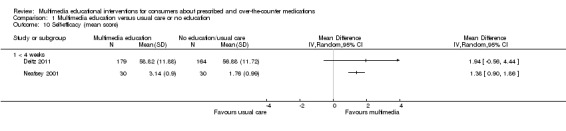

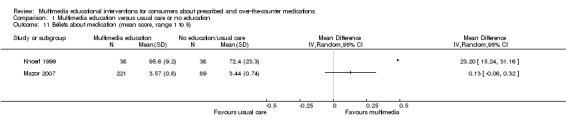

Self‐efficacy Self‐efficacy for medication adherence (higher score indicates greater self‐efficacy, scale not reported) |

The mean self‐efficacy in the control group was 56.88 | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention group was 1.94 higher (0.56 lower to 4.44 higher) | 343 (1 study) |

++OO lowa,c | 1 further study with 99 patients measured self‐efficacy for avoiding drug interactions (scale of 1 to 5) and found that mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 1.38 higher (0.9 to 1.86 higher). The quality of the evidence was lowa,c. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. All of the studies had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors or both.

b. Considerable statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 89%). However, all but one of the studies (Deitz 2011) favoured the multimedia group. Heterogeneity may be due to variability in the education provided to the control group as part of usual care.

c. Results are from only one study.

d. Wide 95% confidence interval including both no effect and substantial effect in the direction of the intervention group.

e. Control groups results measured at the same time point as was used in the meta‐analysis were used to calculate mean scores across the included studies.

f. Three assumed baseline risks were provided based on the control group risks in the included studies (low and high risk) and the median risk across the two studies (medium).

g. The study was at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings: multimedia education compared with written education.

| Multimedia education compared with written education for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education Comparison: written education | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| written education | multimedia education | |||||

|

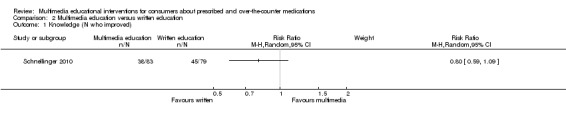

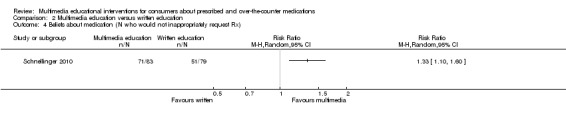

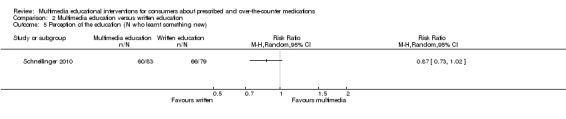

Knowledge (number whose knowledge score improved) Follow‐up: one day |

570 per 1000a | 458 per 1000 (336 to 621) |

RR 0.80 (0.59 to 1.09) | 162 (1 study) |

+OOO very lowb,c | More patients had perfect scores at baseline in the multimedia group (241 versus 165 per 1000). Improvement could not be detected in these patients which may have biased results in favour of written education. |

|

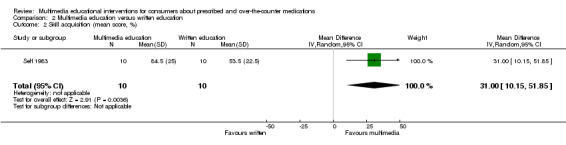

Number who improved on skill

(global inhaler technique rating) Follow‐up: mean one hour |

Low risk populationd | RR 2.14 (1.33 to 3.44) | 164 (2 studies) | +++O moderatee | 1 further study with 20 participants reported that mean inhaler technique score (%) was 31 higher (10.15 to 51.85 higher) in the intervention group. The quality of the evidence was lowb,c. | |

| 180 per 1000 | 385 per 1000 (239 to 619) | |||||

| Medium risk populationd | ||||||

| 222 per 1000 | 475 per 1000 (295 to 764) | |||||

| High risk populationd | ||||||

| 260 per 1000 | 556 per 1000 (346 to 894) | |||||

| Compliance with medication | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured compliance with medication. |

| Health outcomes ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured health outcomes. |

| Medication side effects ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured medication side effects. |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured quality of life. | |

| Self‐efficacy ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured self‐efficacy. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. The assumed risk was calculated from the mean baseline risk in the single study included in the meta‐analysis.

b. The study had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors.

c. Results are from only one study.

d. Three assumed baseline risks were provided based on the control group risks in the included studies (low and high risk) and the median risk across the two studies (medium).

e. Studies had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings: multimedia education compared with education by a health professional.

| Multimedia education compared with education by a health professional for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education Comparison: education by a health professional | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| education by a health professional | multimedia education | |||||

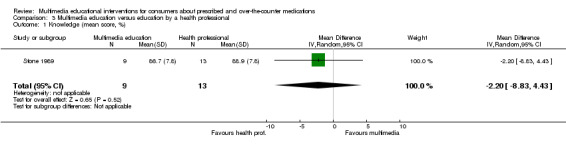

| Knowledge Mean number of correct responses (%). Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: mean 1 day | The mean knowledge in the control groups was 88.9 %a | The mean knowledge in the intervention groups was 2.2 lower (8.83 lower to 4.43 higher) | 22 (1 study) | +OOO very lowb,c | ||

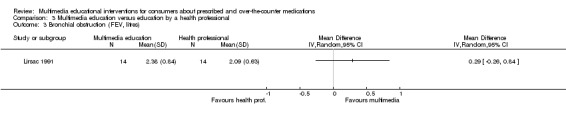

| Skill acquisition (< 4 weeks) Mean inhaler technique score (%), higher score indicates better technique. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 0 to 2 weeks | The mean skill acquisition (< 4 weeks) in the control groups was 76.7%a | The mean skill acquisition (< 4 weeks) in the intervention groups was 1.01 lower (15.75 lower to 13.72 higher) | 130 (3 studies) | +OOO very lowd,e,f | Two studies with 130 patients reported skill acquisition at 4 weeks of more and found that mean inhaler technique score (%) was 4.29 lower (17.23 lower to 8.65 higher) in the intervention group. The quality of the evidence was lowd,e. | |

| Compliance with medication ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured compliance with medication. |

|

Health outcomes Bronchial obstruction (FEV), higher score indicates less bronchial obstruction. Theoretical maximum scores were 2.72 for the multimedia and 3.14 for the control group. Follow‐up: 15 days |

The mean FEV (at 15 days) in the control group was 2.09a | The mean FEV (at 15 days) in the intervention group was 0.29 higher (0.26 lower to 0.84 higher) | 28 (1 study) |

+OOO very lowc,e,g | ||

| Medication side effects ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured medication side effects. |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured quality of life. |

| Self‐efficacy ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured self‐efficacy. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; MD: Mean Difference; FEV: Forced Expiratory Volume | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Control groups results measured at the same time point as was used in the meta‐analysis were used to calculate mean scores across the included studies.

b. The study was at high risk of bias due to lack of allocation concealment.

c. Results were based on one study with a small sample size and wide 95% confidence interval.

d. All of the studies had unclear risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors. All of the studies except Lirsac 1991 also had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

e. Wide 95% confidence interval including both no effect and substantial effect.

f. Substantial statistical heterogeneity (I² = 68%) which may be due to differences in the education provided to the control group.

g. The study had unclear risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessors.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings: multimedia education compared with written education and education by a health professional.

| Multimedia education compared with written education and education by a health professional for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education Comparison: written education and education by a health professional | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| written education and education by a health professional | multimedia education | |||||

| Knowledge ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured knowledge. |

| Compliance with medication ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured compliance with medication. |

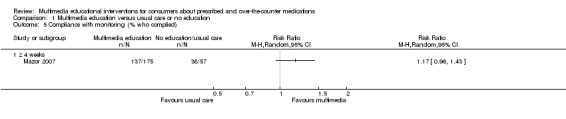

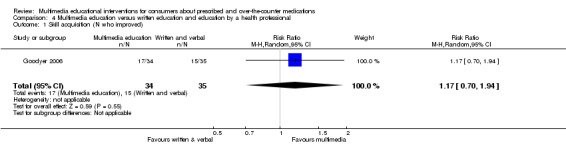

| Number who improved on skill (rating of inhaler technique) Follow‐up: mean 1 day | 429 per 1000a | 502 per 1000 (300 to 832) | RR 1.17 (0.7 to 1.94) | 69 (1 study) | +OOO very lowb,c | |

| Health outcomes ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured health outcomes. |

| Medication side effects ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured medication side effects. |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured quality of life. |

| Self‐efficacy ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured self‐efficacy. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. The assumed risk was calculated from the mean baseline risk in the single study included in the meta‐analysis.

b. The study had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

c. Results were based on a single study with a relatively small sample size and wide confidence interval.

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings: multimedia education compared with control multimedia.

| Multimedia education compared with control multimedia for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education Comparison: control multimedia | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| control multimedia | multimedia education | |||||

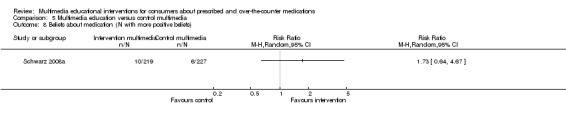

| Knowledge Mean number of correct responses (%). Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 3 to 6 months | The mean knowledge in the control groups was 61%a |

The mean knowledge in the intervention groups was 2.78 higher (1.48 lower to 7.05 higher) | 568 (2 studies) | +++O moderateb | ||

|

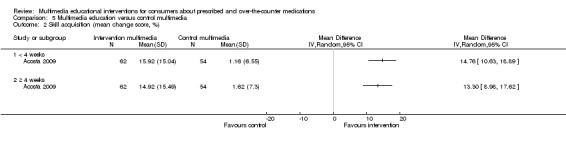

Skill acquisition Inhaler technique (scored 0 to 100 and reported as change in score from baseline) Follow‐up: 1 month |

The mean change in inhaler technique score in the control group was 1.62 out of 100a | The mean change in inhaler technique score in the intervention group was 13.3 higher (8.98 to 17.62 higher) |

116 (1 study) |

++OO lowb,c | Data from the last time point at which the outcome was measured included in the 'Summary of findings' table. | |

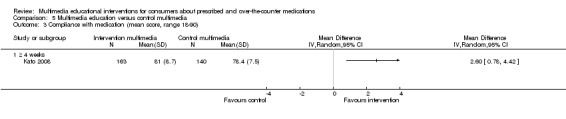

| Compliance with medication. Mean score of the Chronic Disease Compliance Instrument (CDCI), higher score indicates better compliance. Scale from: 18 to 90. Follow‐up: 3 months | The mean compliance with medication in the control groups was 78.4 out of 90a | The mean compliance with medication in the intervention groups was 2.6 higher (0.78 to 4.42 higher) | 303 (1 study) | ++OO lowc,e | ||

|

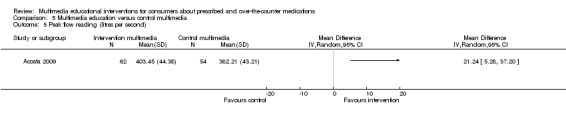

Health outcomes Peak expiratory flow readings (higher readings indicate better peak flow) Follow‐up: 1 day |

The mean peak flow in the control group was 382d | The mean peak flow in the intervention group was 21 higher (5.28 to 37.20 higher) |

116 (1 study) |

++OO lowb,c | ||

| Medication side effects ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured medication side effects |

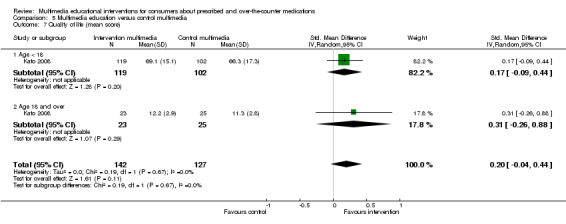

| Quality of life (QOL). Outcome was measured on different scales in different studies (higher score indicates better QOL) Follow‐up: mean 3 months | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.2 higher (0.04 lower to 0.44 higher) | 269 (1 study) | +++O moderatec | A standard deviation of 0.2 represents a small difference between groups. SMD 0.2 (‐0.04 to 0.44) | ||

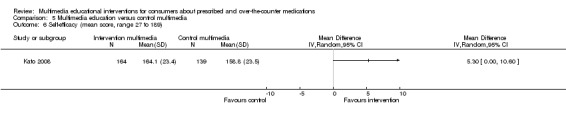

| Self‐efficacy. Self efficacy score (higher score indicates greater self‐efficacy). Scale from: 27 to 189. Follow‐up: mean 3 months | The mean self‐efficacy in the control groups was 158.8 out of 189a | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 5.3 higher (0 to 10.6 higher) | 303 (1 study) | +++O moderatec | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Control groups results measured at the same time point as was used in the meta‐analysis were used to calculate mean scores across the included studies.

b. One or more of the studies had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

c. Results are based on only one study.

d. The assumed risk was calculated from the mean baseline risk in the single study included in the meta‐analysis.

e. Baseline compliance levels were higher in the intervention group.

Summary of findings 6. Summary of findings: multimedia education and a co‐intervention compared with co‐intervention alone.

| Multimedia education and a co‐intervention compared with the co‐intervention alone for prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients taking prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications or their carers Intervention: multimedia education and a co‐intervention Comparison: co‐intervention alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| co‐intervention alone | multimedia education and a co‐intervention | |||||

| Knowledge (< 4 weeks) Mean number of correct responses (%). Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: 2 to 14 days | The mean knowledge (< 4 weeks) in the control groups was 68.76%a | The mean knowledge (< 4 weeks) in the intervention groups was 24.59 higher (22.34 to 26.83 higher) | 381 (2 studies) | +++O moderateb | 1 study with 60 patients measured mean knowledge (%) at 4 weeks or more and found it was 23.3 higher (12.82 to 33.58 higher) in the intervention group. The quality of the evidence was lowb,c. | |

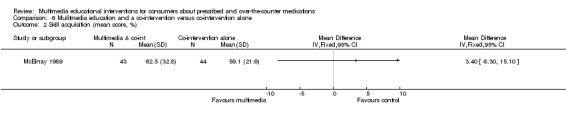

| Skill acquisition Mean inhaler technique score (%), higher score indicates better technique. Scale from: 0 to 100. Follow‐up: mean 2 weeks | The mean skill acquisition in the control groups was 59.1%a | The mean skill acquisition in the intervention groups was 3.4 higher (8.3 lower to 15.1 higher) | 87 (1 study) | +OOO very lowb,c,d | ||

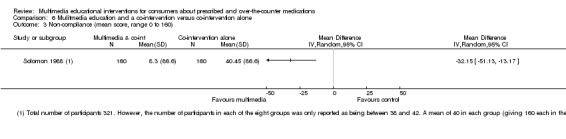

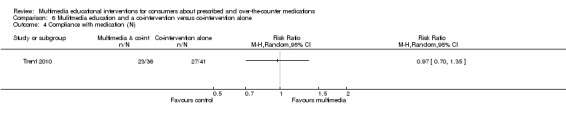

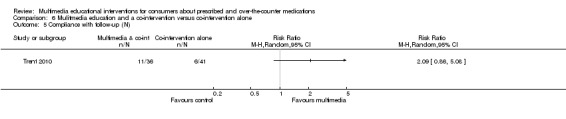

| Non‐compliance with medications score Mean non‐compliance score (lower scores indicate better compliance). Scale from: 0 to 160. Follow‐up: 2 to 6 days | The mean non‐compliance score in the control groups was 40.45 out of 160a | The mean non‐compliance score in the intervention groups was 32.15 lower (51.13 to 13.17 lower) | 320 (1 study) | ++OO lowb,c | 1 further study with 77 patients measured the number who completed their course of medications and found that this was 659 versus 639 per 1000 in the intervention and control groups respectively (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.35). The quality of the evidence was lowc,d. | |

|

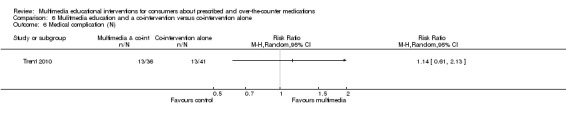

Health outcome (Number who had a medical complication of pelvic inflammatory disease) Follow‐up: two weeks |

317 per 1000e | 361 per 1000 (193 to 675) |

RR 1.14 (0.61 to 2.13) | 77 (1 study) |

++OO lowc,d | |

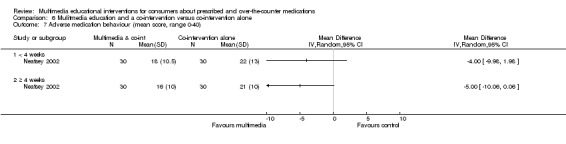

| Medication side effects Mean adverse self‐medication behaviour score (lower scores indicate safer self‐medication behaviour). Scale from: 0 to 40. Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | The mean medication side effects in the control groups was 21 out of 40a | The mean medication side effects in the intervention groups was 5 lower (10.06 lower to 0.06 higher) | 60 (1 study) | +OOO very lowb,c,f | Data from the last time point at which the outcome was measured included in the 'Summary of findings' table. | |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies measured quality of life |

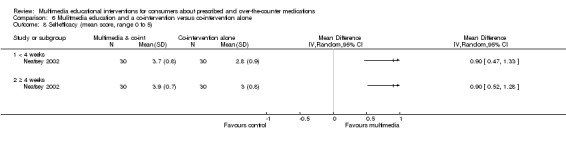

| Self‐efficacy Self‐efficacy rating scale (higher score indicates greater self‐efficacy). Scale from: 1 to 5. Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks | The mean self‐efficacy in the control groups was 3 on 1‐5 rating scalea | The mean self‐efficacy in the intervention groups was 0.9 higher (0.52 to 1.28 higher) | 60 (1 study) | ++OO lowb,c | Data from the last time point at which the outcome was measured included in the 'Summary of findings' table. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

a. Control groups results measured at the same time point as was used in the meta‐analysis were used to calculate mean scores across the included studies.

b. The studies had unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment.

c. Results were based on only one study.

d. Wide 95% confidence interval including both no effect and substantial effect in the direction of the multimedia group.

e. The assumed risk was calculated from the mean baseline risk in the single study included in the meta‐analysis.

f. Outcome measures patient behaviours that are likely to cause medication adverse effects rather than measuring medication adverse effects directly.

Background

Patient education about medications

Health consumers increasingly want access to accurate, evidence‐based information about their health condition and its treatment. There is evidence, however, that current methods for delivering this information are not meeting their needs. Studies have shown a mismatch between health professionals' and health consumers' views about the amount and type of information patients should receive about their medications (Berry 1997; Nair 2002). These groups also appear to have different priorities relating to the purpose of medication information (Grime 2007). Health consumers generally want more information than is provided to facilitate informed decision making, presented in a way that is easy to understand; whereas health professionals focus upon the need to improve medication compliance, save consultation time and establish medico‐legal evidence of informed consent.

Formats for delivering educational materials

For information to be useful for health consumers it needs to be presented in a format that they can understand. Currently, patient information about medications is presented predominantly via spoken communication between the health provider and consumer, sometimes supplemented with written materials. Studies have shown that patients find it difficult to retain information told to them by their doctors, with 40 to 80% of information forgotten immediately (Ley 1982). The amount of information retained is inversely proportional to the amount of information presented, and almost half of the information that is retained is remembered incorrectly (Kessels 2003). Written information that is provided to reinforce verbal communication has been shown to produce variable results. A Cochrane review of written information for consumers about medications found that while some studies showed that patients given written information had improved knowledge about their medications, overall the results were mixed (Nicolson 2009). Moreover the quality of written materials about medications may vary, particularly with respect to their content, structure and usability (Buchbinder 2001; Clerehan 2005; Clerehan 2009).

Potential value of multimedia education programs

Multimedia education programs which provide information using more than one format offer many potential advantages over traditional forms of information delivery. The combination of audio with graphic presentation of information, or the use of animation or video may overcome barriers that poor literacy creates for some consumers (Liao 1996; Wofford 2001). Multiple studies have shown that learning is improved when students are presented with information in an audiovisual, rather than visual only, format (Kalyuga 2000; Mayer 1998; Moreno 1999; Tindall‐Ford 1997). As opposed to spoken communication from a health professional, multimedia education programs can be viewed at a pace that suits the consumer, with information repeated as required. They can be provided using different technologies, many of which are portable or can be accessed over the Internet. This allows consumers and their families to access the information at a time and place that is convenient for them, and the information to be widely disseminated at little cost. The anonymity provided by the programs may allow patients to access information that they may be uncomfortable requesting from their doctor. One of the advantages of multimedia programs over written materials is that they often allow information to be tailored, or personalised, to individual patients and their needs. Tailored information is more likely to be used and viewed as relevant compared with generic information. There is also some evidence that it may be more effective at modifying health‐related behaviours (Lustria 2009).

Multimedia programs vary in their interactivity, which is defined as the degree of user control and program responsiveness. User control is the ability of the user to alter the form and content of a program, select topics or services and the order in which they are presented, and respond to information presented. Responsiveness is the degree to which a program is able to take into account and respond to the actions of the user. Interactivity increases user engagement, active information processing and satisfaction, and increases the effectiveness of educational materials (Street 1997).

Like any other information format, multimedia education programs may also vary in content accuracy. Additional quality concerns include the ease with which the written, spoken or graphical information is understood, and the usability of the program. The way the program is delivered may also result in the exclusion of certain sections of the population who do not have access to the technology or the technical knowledge required to use it. This may be a particular problem for people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and/or the elderly (Bozionelos 2004; Wright 2009).

The impact of patient education about medications

Tones 1994 defined health education as any intentional activity which is designed to achieve health‐ or illness‐related learning. Information about medications which aims to produce changes in areas including knowledge, beliefs, skills and behaviours would meet this definition for health education. The aims and therefore the relevant outcomes of health education vary. The most direct effect of education would be to increase knowledge and skill levels. Health consumers who are prescribed medications are expected to perform certain self‐management tasks. These include making an informed decision about taking the medication, self‐administering the medication at the right dose and time, monitoring their response to treatment, recognising side effects of the medication and alerting health professionals if they are not responding or develop side effects. These self‐management tasks are particularly important for those suffering chronic conditions. Many health consumers may take multiple medications which makes self‐management more complex and increases the risk of adverse events (Gray 2009). To perform these tasks successfully, health consumers require detailed information about their medications.

Increased knowledge about medications may lead to changes in health‐related behaviour and improved health outcomes. However, a recent overview of systematic reviews evaluating the effects of consumer‐oriented interventions on medicines use suggests that patient education limited to information provision alone is insufficient to effect change (Ryan 2011). Guidelines for the management of asthma recommend the use of additional strategies including patient self‐monitoring, regular medical review and the used of a written action plan, which, in combination with patient education, have been shown to improve health outcomes (Gibson 2002). Ryan's overview supports this approach, finding that interventions that included self‐monitoring and self‐management, and possibly the combination of education with self‐management, show promise in improving adherence and medicine use (Ryan 2011). There may also be more direct effects of education on patients’ emotions, beliefs and attitudes as well as health‐related behaviour, which have not been evaluated in these reviews.

Much of the literature related to patient education about medication and behaviour change has focused upon medication compliance or adherence, which is defined as the degree to which a person’s behaviour coincides with medical advice. This assumes that the patient has a passive role in accepting medical direction (Bajramovic 2004). Studies of educational interventions about medications have shown mixed effects on compliance, with some interventions successfully increasing knowledge without a resulting increase in compliance rate (Brus 1998; Cote 1997). A Cochrane review found that interventions that were effective for improving patient compliance with long‐term treatments were typically complex and multi‐faceted (Haynes 2008). The failure of educational interventions to improve compliance rates may be due to the frequency of intentional non‐compliance. This is where patients deliberately choose, for reasons such as side effects or perceived lack of effectiveness, not to take their medication as prescribed (Lowe 2000). These decisions are often not reported back to the treating doctor.

More recently, the emphasis in medication prescription has shifted from 'compliance' to 'concordance'. Concordance entails a partnership, with two‐way communication between the patient and the health professional. The patient is encouraged to share their preferences and beliefs, is fully informed about the benefits and risks of treatment, and participates as a partner with the health professional in reaching agreement about treatment (Stevenson 2004). This collaborative approach to prescribing medications, whereby the patient is involved in the discussion and decision‐making process, has been shown to improve patients’ knowledge and initial beliefs about the medication, medication use, and satisfaction with both medication and care (Bultman 2000). Patient education about treatment is a vital component of the concordance model. However, concordance is difficult to measure, and it has not been widely adopted as an outcome measure for evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions. Patient‐reported outcomes measuring health consumers' perception of components which make up the concordance model are more readily measurable. These may include their attitudes and beliefs about medications, satisfaction with the education and care they received, participation in decision making, and confidence in their ability to perform health‐related tasks (self‐efficacy).

As well as examining the benefits of patient education, it is also important to ensure that it is not causing any harm. There is evidence that medication compliance is not decreased by informing patients of a medication's potential adverse events (Haynes 2008). However, particular studies have raised concern that informing patients of all potential risks of a medication may increase anxiety and the incidence of medication side effects by suggestion, overload them with too much information from which they will be unable to weigh potential risks against benefits, and lead to their missing out on beneficial treatments (Fraenkel 2002; Pullar 1990).

Relationship to other reviews

This review covers multimedia education about medications for any condition, and therefore is likely to overlap with other existing Cochrane and non‐Cochrane reviews. Two reviews, performed in 2005 and 2008, examined randomised controlled trials of multimedia patient educational interventions (Jeste 2008; Wofford 2005). The reviews used different definitions for multimedia: Wofford 2005 defined it as using graphics (animation or video) and/or audio with or without the use of supporting text, while Jeste 2008 defined it as utilising both an auditory‐verbal channel and a visual‐pictorial channel. Wofford 2005 limited interventions to those that utilised desktop computers for delivery, therefore excluding interventions delivered as videotapes or using portable devices. Jeste 2008 excluded interventions aimed at carers and studies that did not report objective measures of knowledge. Both reviews excluded studies that were not published in English and had study participants less than 18 years of age. Our review is more comprehensive in that we did not restrict inclusion to studies published in English, nor by age or category of health consumer, and we considered a wide range of outcomes, including interventions targeted to carers and outcomes for carers. Our definition of multimedia is also broader. Although both reviews focused on educational interventions they also included decision aids and interventions providing counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy, emotional support and case management. They also included interventions that contained multiple components, where the effect of multimedia education on outcomes could not be separated from the effect of other components of the intervention.

The Cochrane review by Murray et al (Murray 2005) deals with Interactive Health Communication Applications (IHCAs) for people with chronic diseases. These are defined as computer‐based information packages for patients that combine health information with at least one other intervention such as decision support, behaviour change support or peer support. Complex programs involving multiple interventions in combination with health information were excluded from our review unless the effect of the multimedia educational intervention on measured outcomes was clearly separated from the impact of the other interventions. Our review will not be limited to people with chronic conditions nor by the type of technology used to deliver the program. IHCAs are, by their definition, interactive, but do not necessarily have a multimedia component. Non‐interactive interventions such as video were therefore not considered in Murray's review.

A number of reviews examine the effectiveness of education, and other types of interventions, at improving medication adherence (Haynes 2008; M'Imunya 2012; Rueda 2006). The M'Imunya and Rueda reviews are disease specific, in that they deal with any type of intervention that aims to improve adherence to treatments for tuberculosis and HIV respectively. The Haynes review is much broader, in that it deals with any type of intervention intended to improve adherence to prescription medications used to treat any condition. All of these reviews focus on adherence and clinical outcomes. However, it is likely that they will contain some studies which overlap with our review. An overview of systematic reviews examines consumer‐oriented interventions for evidence‐based prescribing and medicines use (Ryan 2011). This overview includes a broad range of interventions and outcomes and may contain studies which overlap with our review.

A number of Cochrane reviews examine self‐management education, particularly for the management of chronic diseases (Effing 2007; Powell 2002; Shaw 2010). Self‐management education teaches skills that allow patients to identify their problems, and provides them with techniques to help them make decisions, take appropriate actions and alter those actions as they encounter changes in circumstance or disease. The development of an action plan is a central feature of this process (Bodenheimer 2002). Education is a key component of self‐management programs. Our review will focus on purely educational interventions where medication‐specific information and technical skills are transferred to a patient. Our review will include studies in which the purpose of this information transfer is to improve self‐management, but will exclude more complex self‐management education programs unless the effect of the multimedia educational component can be separated from the effect of the other components of the program.

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the potential benefits of multimedia compared with traditional methods of patient education delivery, there is concern that the application of these programs may precede evidence of their effectiveness (Robinson 1998). The development and production of multimedia programs is expensive, especially when this is compared to the limited cost involved in producing information leaflets. Although there have been a number of Cochrane reviews in the area of patient education, this will be the only review that looks specifically at the effects of multimedia presentation of information related to medication on knowledge, skills, and health outcomes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of multimedia patient education interventions about prescribed and over‐the‐counter medications in people of all ages, including children and carers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (in which methods of allocating participants to treatment are not strictly random, e.g. using alternation, date of birth, or some similar method of allocation). Some studies professing to be RCTs are actually quasi‐RCTs. However, this can only be determined during a risk of bias assessment and only in studies that adequately report their methods for randomisation. We therefore decided to include all RCTs and quasi‐RCTs and then deal with randomisation issues in the Risk of bias in included studies and in sensitivity analysis. Studies that randomised individuals or cluster‐randomised trials that randomised by groups, for example by medical practice, were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participants included people of all ages who had been prescribed (or directly administered by a health professional) a particular medication or medication regimen, or who had obtained an over‐the‐counter medication. We included children and carers if the intervention had been targeted for their use. Participants also included people who were provided with education about a particular medication, medication regimen or over‐the‐counter medication but who had not been prescribed or obtained the medication.

We excluded studies relating to unlicensed medications and complementary medicines, including vitamins and nutritional supplements.

Types of interventions

We included studies of multimedia‐based patient education about prescribed or over‐the‐counter medications.

Intervention format

Multimedia was defined as the delivery of information using a combination of formats. Formats were divided into:

text, still graphics or photographs

animation and video

audio

We included interventions that delivered information using a combination of at least two different formats. However, we excluded interventions if they contained only text with still graphics or photographs, e.g. printed pamphlets with pictures or Internet pages with text and still pictures.

We included multimedia interventions which were interactive or tailored. All mechanisms for delivering multimedia programs (such as web‐based, DVD and CD‐ROM) were included in the review. We included studies that evaluated multimedia interventions directed at participants both before they had started their medication and once they were already taking it.

Intervention content

For the study to be included in the review, the educational intervention must have included information or education about a particular medication or group of medications as its primary focus. We excluded interventions that did not contain an education component (e.g. electronic history taking).

Complex programs that included a multimedia education program as part of a number of interventions were only included if the impact of the multimedia intervention on measured outcomes could be clearly separated from the effect of the other interventions. Decision aids, which are primarily designed to assist consumers in choosing between treatment options, were not included. The intervention must have been designed to inform or educate health consumers or their carers. We excluded interventions that were aimed at educating health professionals.

Comparison interventions

The main comparison groups included:

no education;

standard or usual care i.e. where no standardised educational intervention is provided as part of the trial but participants received non‐standardised education from health professionals involved in their care;

other forms of education (not using the multimedia format)

a control multimedia education program that provides generic information, or information not pertaining to the medication or treatment being considered in the study.

The content of the comparison interventions was assessed in the same way as for the multimedia educational interventions.

Types of outcome measures

The type of outcomes reported was not used to determine study eligibility for inclusion. Both binary and continuous outcomes were selected as appropriate. We extracted data, when available, for all of the following outcomes for each of the trials, extracting data at all time points measured.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were:

Patient or carer knowledge about the medication. Increased knowledge about a medication was considered the most direct effect of an educational intervention.

Any measure of skill acquisition related to the medication (e.g. ability to administer injectable medications appropriately).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

Health‐related behaviour, including medication compliance/adherence or concordance.

Health outcomes, including disease‐related outcomes and safety data including adverse events related to the medication.

Patient‐ or carer‐reported outcomes: these were varied and included quality of life, self‐efficacy, emotions (including anxiety caused by the educational intervention), beliefs and attitudes about the medication, satisfaction with the care and education received, and the user's perception of the quality and usability of the educational intervention. Outcomes relating to self‐management itself (such as perception of ability to self‐manage) were included here, while measures of ability to perform specific self‐management tasks (such as safely self‐administer medication) were included under skill acquisition in the primary outcomes.

Participant usage of the intervention.

Cost, including the cost of health care, the cost‐effectiveness of the educational intervention, and resource utilisation such as the number of hospital admissions and medical reviews.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases and sources to identify studies:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library) to June 2011;

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1950 to June 2011;

EMBASE (Ovid) 1974 to June 2011;

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) 1982 to June 2011;

PsycINFO (Ovid) 1967 to June 2011;

ERIC (Educational Resources Information Centre) 1966 to June 2011;

ProQuest Dissertation & Theses Database to June 2011.

We present the search strategies in Appendix 1 to Appendix 7. There were no language restrictions.

Searching other resources

We systematically searched the reference lists of reviews that potentially overlapped with our review, reviews identified by our search strategy and the studies retrieved in full text, to identify potentially relevant studies. We also checked the personal records of the review authors to identify any further studies for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SC, RJ) independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified studies for possible inclusion, and removed duplicate records of the same report. The full text of all potentially‐relevant studies were retrieved and assessed for inclusion. If studies had insufficient information on which to base a decision, we contacted the study authors to obtain further information. Disagreements regarding inclusion were resolved by discussion and consensus, or by consulting a third author. Relevant studies that we excluded are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table with the primary reason for exclusion given.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SC, RJ) independently extracted data from all included studies using a form derived from the data extraction template of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or through a third party. Extracted data included details about the participants, the intervention, the outcomes assessed and the study results. Extracted data were summarised in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Data extracted about participants included general demographics information and where available, information about: their literacy (as defined or reported by the study authors); educational level; the medical condition being treated; their co‐morbidities; and other medications they were receiving.

Information extracted about the intervention included the format or media used, when and how it was delivered, whether it reached its intended audience, and details regarding the type and degree of interactivity or tailoring.

Based upon systemic functional linguistics, two of the authors (RC and RB) have previously developed a linguistic framework, the Evaluative Linguistic Framework (ELF), for evaluating the quality of medication leaflets intended for patients (Clerehan 2005; Clerehan 2009). From this work, which included consumer input about what information needs to be included (Hirsh 2009), we found that medication leaflets have an identifiable generic structure that may include up to ten 'moves' or identifiable sections.

These include:

Background of the drug;

Summary of use of drug;

Dosage instructions;

Outline of benefits of drug;

Account of side‐effects;

Information regarding monitoring required e.g. regular blood tests

Constraints on patient behavior (including information about drug interactions);

Contraindications to use;

Storage instructions; and

Clinical contact availability

We contacted study authors to request access to the multimedia intervention. Where this was not made available, our evaluations were based on descriptions of the intervention from the studies. The specific content of the multimedia educational interventions was extracted and assessed according to the ten ELF content areas.

In addition, we systematically evaluated and report the quality of the multimedia intervention according to the ELF (Clerehan 2009) (Table 7). The ELF was specifically developed for written patient information and was adapted for assessment of the quality of multimedia patient education interventions. It considers the generic or overall structure of the intervention, its rhetorical elements (function of each section, such as to define, instruct or inform the reader), nature of the relationship between the developer and reader (such as medical expert to layperson, etc), metadiscourse (description of the purpose or structure of the text), headings, the technicality of the medical terminology, density of the content words (or 'lexical density') and its factual content. We documented whether literacy, format, readability and usability issues were considered. In addition we determined whether health consumers were involved in its development.

1. Framework for evaluating healthcare text based upon systemic functional linguistics.

| Item | Description | Assessment |

| Overall organisational or generic structure of the text | Series of stages or moves in a text (e.g. background on drug, dosage instructions, account of side effects) | What identifiable sections of text (moves) are present? Are all essential moves included? What is the sequence of moves and is this appropriate? |

| Rhetorical elements | The function of each move in relation to the reader (e.g. to define, instruct, inform) | What are the rhetorical functions of each move in relation to the reader? Are these clearly defined and appropriate? Is there clear guidance about what to do with the presented information? Are instructions clear about what action needs to be taken? |

| Relationship between writer and reader | Nature of the relationship between the writer and reader (e.g. medical expert to layperson; doctor to his/her patient) | Is it clear who the writer and intended audience is? Is the relationship between writer and reader clear and consistent? Is the person who is expected to take responsibility for any actions clear? Is the importance and/or urgency of the action made clear? How positive (encouraging, reassuring) is the tone? |

| Meta discourse | Description of the purpose/structure of the text | Is there a clear description of the purpose of the text? |

| Headings | Signposts in the text for the reader | Are headings present? If present, are they appropriate? |

| Technicality of vocabulary | The technicality of the medical terminology/other vocabulary that is used | How technical is the vocabulary that is used in the text? Is this appropriate? |

| Lexical density | Density of the content words in the text | What is the average content density of the text (percentage of content‐bearing words)? Is this appropriate? |

| Factual content of text | Facts included in the text | Is the factual information correct and up‐to‐date? Is the source of information provided? Is the quality and strength of the evidence discussed? |

| Format | Visual aspects such as layout, font size, style, use of visual material, etc. | What is the length, layout, font size and visual aspect of the document? |

If a trial included multiple measures of a particular outcome (e.g. knowledge), we extracted only one of these measures to prevent double counting. If the study identified one of the measures as the primary outcome, or specified it in its sample size calculation, then we extracted these data. Otherwise the decision as to which measure to extract was made by consensus opinion of the authors, based on the clinical importance of the outcome, whether the measure had been validated and found to be reliable, and its similarity to those reported in other studies. Authors involved in this decision were blinded to the results for each of the outcomes.

Where studies reported outcomes at more than one time point, we examined and reported data at all time points to determine if the effects of the intervention, particularly on acquisition of knowledge and skills, persisted or changed over time. For the meta‐analysis we decided to divide time points into those that were short‐term (< 4 weeks) and long‐term (≥ 4 weeks) and if there were multiple time points within these categories, we extracted data from the last time point measured. This division of time points was a post‐hoc decision based on the range of time points reported by the included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported the risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011a), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding, incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. For each of these domains, we described the methods used in each study, and made a judgment about the risk of bias using the guidelines in Higgins 2011a, with each domain judged as having low, high or unclear risk of bias. Blinding was assessed for both participants and outcome assessors. Studies were judged to be at low risk of bias if both the participants and assessors were adequately blinded; if the outcomes measured were objective and unable to be influenced by lack of blinding or if the assessment occurred immediately following the intervention, minimising the potential for the lack of blinding of participants to influence outcomes. We also examined the method of intervention delivery to determine if it had the potential to cause selection bias; for example, inadvertently selecting participants from higher socioeconomic backgrounds or with higher levels of educational attainment by only including participants who have access to certain technologies. We contacted study authors for additional information about the included studies, or for clarification of the study methods as required. We incorporated the results of the 'Risk of bias' assessment into the review through systematic narrative description and commentary about each of the elements, leading to an overall assessment of the risk of bias of included studies, a judgement about the internal validity of the review’s results and a GRADE assessment of the quality of evidence for each outcome (Schünemann 2008b).

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed separately studies that compared the multimedia intervention to no intervention (including usual care), to other forms of education (written information, education by a health professional or both) and to other multimedia interventions, as well as those that compared multimedia in combination with a co‐intervention to the co‐intervention alone. Effects were expressed as mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes, if individual studies used different scales to measure the same outcome (and results could not be converted into the same scale) then we used standardised mean differences (SMD).

Unit of analysis issues

We intended that potential unit of analysis errors, caused by cluster randomised trials failing to appropriately account for correlation of observations within clusters, would be corrected by incorporating an approximate analysis of the trial using methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011b).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to obtain missing statistical data. Outcomes were analysed using intention‐to‐treat results where possible. Where this was not possible, the data were analysed as reported by the study authors. We reported the number of participants lost to follow‐up and reasons given for attrition in each study as part of the 'Risk of bias' assessment. We calculated missing standard deviations (SDs), where possible, from other reported statistics (Higgins 2011c). Where this was not possible, the SD was imputed from the most representative study; i.e. the study with the greatest weight on the meta‐analysis. The possible impact on missing data on the findings of the review was investigated in sensitivity analyses, and discussed in the review (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before meta‐analysis, studies were assessed for clinical homogeneity with respect to type of multimedia program, control group, and the outcomes measured. Clinically heterogeneous studies were not combined in the analysis, but separately described. For studies judged as clinically homogeneous, we tested for statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test. We interpreted the Chi2 test as indicating significant statistical heterogeneity if the Chi2 significance (P value) was less that 0.10. This value was chosen instead of the conventional significance level of 0.05 to counteract the low power of the Chi2 test when meta‐analyses contain studies with small sample sizes or that are few in number. In order to assess and quantify the possible magnitude of inconsistency across studies, we examined the I2 statistic. The I2 statistic describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. It was interpreted as: 0% to 40% representing heterogeneity that may not be important; 30% to 60% representing moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% representing substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100% representing considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess publication bias graphically using a funnel plot if there were at least 10 studies included in the meta‐analyses of the primary outcomes (knowledge and skill acquisition) (Sterne 2011). However, we identified fewer than 10 studies, precluding the analysis.

We assessed the potential for 'small sample' reporting bias by investigating whether the random‐effects model produced similar effect sizes as the fixed‐effect model. In the presence of small‐study effects, the intervention effect is more beneficial in the smaller studies, and the random‐effects estimate of the intervention effect will be more beneficial than the fixed‐effect estimate (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

All trials, regardless of their assessed risk of bias, were pooled in the primary analysis. We pooled studies using the random‐effects model due to the likely heterogeneity of the multimedia interventions being evaluated. We presented results for each of the outcomes, organised by the comparison intervention:

Multimedia compared to no education or usual care

-

Multimedia compared with other forms of education

written education

education by a health professional

written education and education by a health professional

Multimedia compared with 'control' multimedia program

Multimedia plus a co‐intervention compared with the co‐intervention alone

We used forest plots to illustrate the results of meta‐analyses where there was more than one study for that outcome. Where there was only one study for a particular outcome, we included the results in the text. We also presented results for all studies in Additional tables (Table 8).

2. Study outcome data.

| Study | Study arms | Timing of follow‐up | N at follow‐up | Outcome | Results |

| Acosta 2009 | Multimedia (I) vs control multimedia (C) | Immediately before (baseline) and after (post) the intervention and after one month. | I: 62 C: 54 |

Skill acquisition (inhaler technique) | Change in score (% correct) from baseline: Post intervention: I: 15.92 (SD 15.04), C: 1.16 (6.55), P < 0.001, mean difference 14.77, 95% CI 10.39 to 19.15. After 1 month: I: 14.92 (SD 15.49), C: 1.62 (SD 7.30) P < 0.001, mean difference 13.30 95% CI 8.74 to 17.86. |

| Peak flow | Post intervention I: 403.45 (95% CI 392.40 ‐ 414.94), C: 382.21 (95% CI 370.42 ‐ 394.01). Results are "controlled for pre‐intervention peak flows". There was no significant difference in pre intervention peak flows readings (C: 409.81, I: 386.94, P = 0.18) | ||||

| Deitz 2011 | Multimedia (I) vs control (C) | After the intervention period | Total post‐test N = 346 I: 181 C: 165 |

||

| N (who completed the knowledge questionnaire) = 329 | Knowledge of prescription drug use and dependency | Mean score (SD): Drug facts I: 13.23 (2.40), C: 12.84 (2.33), P = 0.025; Smart use I: 13.1 (1.63), C:12.9 (1.43), P = 0.457; Manage health I: 6.48 (0.96), C: 6.40 (0.89), P = 0.127. Maximum score for the scales was not reported. | |||

| 1. N = 345 2. N = 343 3. N = 342 |

Self efficacy: 1. Self‐efficacy in obtaining medical information and attention to their concerns from their doctor (PEPPI) 2. Medication adherence self‐efficacy (Medication Adherence Survey) 3. Self efficacy in managing medication problems (Ability to Manage Problems Survey) |

1. Mean score (SD): I: 17.85 (4.33), C: 17.70 (4.30), P = 0.687. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. 2. Mean score (SD): I: 58.82 (11.88), C: 56.88 (11.72), P = 0.013. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. 3. Mean score (SD): I: 28.05 (3.99), C: 27.34 (3.83), P = 0.026. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. |

|||

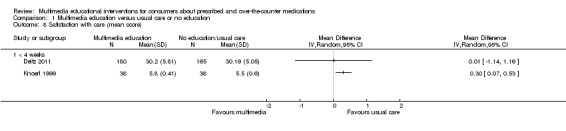

| N = 345 | Patients' perception of the therapeutic alliance with care givers and degree of satisfaction with treatment (Patient feedback survey) | Mean score (SD): I: 30.20 (5.81), C: 30.19 (5.05), P = 0.744. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. | |||

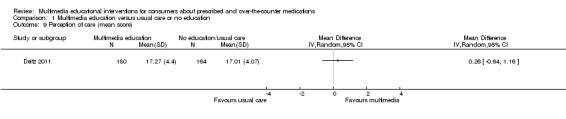

| N = 344 | Patients' perception of the degree of directive guidance (instructions on taking their medication properly) given by doctors and pharmacists (Purdue) | Mean score (SD): I: 17.27 (4.40), C: 17.01 (4.07), P = 0.749. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. | |||

| N = 329 | Patients' perception about their current drug use and whether it is problematic (CAGE) | Mean score (SD): I: 0.485 (0.83), C: 0.861 (1.19), P = 0.038. Maximum score for the scale was not reported. | |||

| N = 344 | Self reported drug taking for non‐medical purposes (sections of the NSDUH) | Odds ratio between intervention and control group (from logistic regression with pre‐intervention non‐medical use entered as a control variable): Non‐medical use of analgesics: OR 0.656, 95% CI 0.147 to 2.92, P = 0.579. Non‐medical use of sedatives: OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.50 to 3.97, P = 0.517. Non‐medical use of tranquillisers: OR 2.09, 95% CI 0.92 to 33.03, P = 0.132. Non‐medical use of stimulants: OR 6.47, 95% CI 0.426 to 98.13, P = 0.179. | |||

| Goodyer 2006 | Multimedia (I) vs written and verbal (V) vs written (C) | Immediately before and after the intervention | I: 34 V: 35 C: 35 |

Skill acquisition (inhaler technique) |

Change in global technique rating. Number who were: worse than baseline I: 5/34, V: 4/35, C: 5/35; same as baseline I: 12/34, V: 16/35, C: 18/35; better than baseline I: 17/34, V: 15/35, C: 9/35. Number who: check mouthpiece I: 16/34, V:11/35, C: 1/35; shake inhaler: I: 24/34, V: 35/35, C: 16/35; co‐ordination I: 11/34, V: 10/35, C: 3/35. |

| Kato 2008 | Multimedia education (I) vs control multimedia (C) | Before the intervention as well as 1 and 3 months later | Number varies for each outcome for the 3 time points. Knowledge: I: 191, 172, 164 C: 168, 146, 139 |

Knowledge about cancer | Mean score (SD). Before I: 59% (20) C: 60% (20); 1 month I: 65% (20) C: 63% (20); 3 months I: 66% (20) C: 63% (20). Significantly greater increase in knowledge over time in intervention group (P = 0.035) |

| CDCI: I: 191, 172, 163 C: 167, 147, 140 MAS: I: 190, 167, 160 C: 166, 146, 138 |

Self‐reported adherence to medications: 1. CDCI (Chronic Disease Compliance Instrument) 2. MAS (Medication Adherence Scale) |

1. CDCI mean score (SD), range of 18‐90 with higher scores representing greater adherence: Before I: 79.2 (7.9), C: 77.4 (7.5); 1 month I: 79 (8.3), C: 78.4 (7.7); 3 months I: 81 (8.7), C: 78.4 (7.5). 2. MAS mean score (SD), range from 0‐4 with higher scores indicating greater adherence: Before I: 2.9 (1.1), C: 2.9 (1.1); 1 month I: 3.0 (1.1), C: 3.1 (1.0); 3 months I: 2.9 (1.1), C: 3.0 (1.1). |

|||

| 6‐MP metabolite assays: I: 28, 24, 23 C: 26, 22, 23 MEMS (only measured at 3 months): I: 107 C: 93 |

Objective measures of adherence to medications: 1. 6 ‐MP adherence using metabolite assays: 6‐TG and 6‐MMP 2. TMP/SMX adherence using Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) |