Large scale emergency, reconstruction, and development aid is needed to rebuild Afghanistan's devastated infrastructure. All sectors, not least the health sector, need massive external support and they need it now, Kieran Prendergast, undersecretary of political affairs at the United Nations, told a meeting of the World Economic Forum in New York last week.

Afghanistan's health statistics are among the worst in the world. Large numbers of people are dying from preventable diseases, and the World Health Organization estimates that six million people have little or no access to medical care. Only about 1 in 4 people has access to clean water.

Hospitals and health centres are denuded of staff, equipment, power, and medicines. For a population of about 23 million people there are only about 17500 health professionals. A quarter of the doctors are in Kabul, where only 7% of the population live. By World Health Organization standards a minimum of 63000 health workers are needed to provide a basic essential service.

The Afghan government lacks the money to pay even basic costs and salaries, and re-establishing a viable health system will take years.

In the short term, Afghanistan will be almost entirely dependent on international aid. Although $4.6bn (£3.2bn; €5.3bn) was pledged at the donor conference in Tokyo it is uncertain when and how much of it will be realised, or how much will filter through to the health sector. Many groups, including Physicians for Human Rights, have emphasised that more aid is needed.

Currently over 70% of health care is being provided by about 20 health related non-governmental organisations, many of whom have been in the country for years. Their continued presence is crucial to setting up the basic primary care services needed to tackle maternal and child mortality, communicable disease, and malnutrition, which the World Bank and United Nations have identified as priorities for action.

With many more non-governmental organisations and donors poised to start individual initiatives the importance—and difficulty—of coordinating their activities was underlined at a recent symposium at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in London.

Stephane Vandam, a health policy expert at the WHO, said: “The international aid and donor community have immense responsibilities to ensure that the health needs of Afghans are being addressed and the new ministry of public health is supported to assume a leadership role.”

Support must avoid creating dependency. “In the rush to provide services fast for the maximum number of people, Western agencies often forget to think about the long term impact of their interventions,” Dr Willem van de Put of the Dutch based non-governmental organisation HealthNet International, told the BMJ.

He added: “Initiatives controlled by Western experts frequently fail. The prime function of NGOs [non-governmental organisations] working in the health sector is to support, train, and empower local health professionals, to build sustainable services, a process which takes time, patience, and sensitivity.”

Maintaining security is essential to establish sustainable health services. It is particularly important in resurrecting the confidence of women doctors, nurses, and traditional birth attendants. Updating their medical and management skills and, through them, training cadres of community workers to help provide local maternal and child health services is vital.

After years of opression, violence and upheaval, cultural awareness and sensitivity are needed on the part of external agencies.

“We have found that our Sudanese employees are more successful at working with local Afghan communities than their Dutch colleagues,” said Dr van de Put.

“Their understanding of the Islamic world and Shariah law greatly enhance their ability to understand their problems. They know when it is time to talk and when to listen and the rituals that must be gone through to establish trust.”

Trust is at a premium in Afghanistan. The transitional government may have international backing, but the chains of command are indistinct.

Some newly appointed provincial governors and others in positions of power are the same men who were occupying these positions before the Taliban took over, and their track records inspire horror rather than confidence.

Recent reprisal attacks and fighting between local ethnic groups have provoked immense concern. In the face of deteriorating security, a call was made by Richard Haass, a US State Department official, at the World Economic Forum, for the size of the peace keeping force to be increased, a call that is echoed today in the BMJ letters pages. (See p 360.)

A report of the symposium held at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine is available from gillreeve@medact.org

Health statistics of Afghanistan

Average life expectancy: 46 years

Maternal mortality rate: 1700 per 100000 live births

Infant mortality rate: 165 per 1000 live births

Probability of death at age 0-5 years: 257 per 1000

Malnutrition: An estimated 50% of children have chronic malnutrition, and 10% acute malnutrition.

Infectious diseases: 72000 new cases of tuberculosis annually. Outbreaks of cholera, malaria, typhoid, leishmaniasis, meningitis, and haemorrhagic fever also recorded.

Landmine injuries and deaths: Before the conflict, 500 or more mine accidents recorded monthly (about 150 fatal).

Data obtained from: www.who.int/disasters/country.cfm? countryID=1&doctype1D=4

Health Relief to Health Reconstruction in Afghanistan. WHO brief, 5 December 2001.

http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/SAR/sa.nsf/Attachments/9/$File/mines. pdf (the World Bank's website)

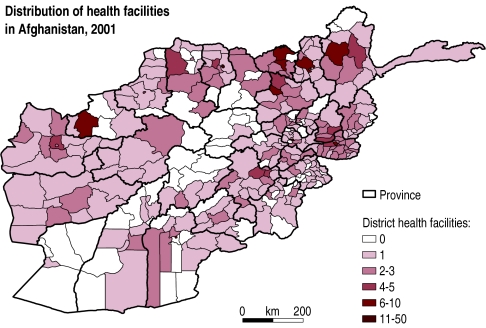

Figure.

Large parts of Afghanistan have few or no health facilities, as this map from the World Health Organization shows. Health facilities are defined as hospitals or health centres that have at least one doctor and one nurse and provide essential drugs for common illnesses. Such centres should provide immunisations, growth monitoring, and antenatal care but some of them do not do so.