Abstract

Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is a prodrug that is mainly bioactivated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2B6 enzyme. Several other enzymes are also involved in its bioactivation and affect its kinetics. Previous studies have shown the effect of the enzymes' genetic polymorphisms on Cy kinetics and its clinical outcome. These results were controversial primarily because of the involvement of several interacting enzymes in the Cy metabolic pathway, which can also be affected by several clinical factors as well as other drug interactions. In this review article, we present the effect of CYP2B6 polymorphisms on Cy kinetics since it is the main bioactivating enzyme, as well as discussing all previously reported enzymes and clinical factors that can alter Cy efficacy. Additionally, we present explanations for key Cy side effects related to the nature and site of its bioactivation. Finally, we discuss the role of busulphan in conditioning regimens in the Cy metabolic pathway as a clinical example of drug-drug interactions involving several enzymes. By the end of this article, our aim is to have provided a comprehensive summary of Cy pharmacogenomics and the effect on its kinetics. The utility of these findings in the development of new strategies for Cy personalized patient dose adjustment will aid in the future optimization of patient specific Cy dosages and ultimately in improving clinical outcomes. In conclusion, CYP2B6 and several other enzyme polymorphisms can alter Cy kinetics and consequently the clinical outcomes. However, the precise quantification of Cy kinetics in any individual patient is complex as it is clearly under multifactorial genetic control. Additionally, other clinical factors such as the patient's age, diagnosis, concomitant medications, and clinical status should also be considered.

1. Introduction

Cancers are a group of diseases which are characterized by disordered and continuous cell growth. Humanity has been dealing with the blight of cancer as early as the ancient Egyptian era; essentially, our medical skills have been unable to satisfactorily manage cancer for thousands of years [1].

Cancers can be divided into solid tumors, such as breast cancer and ovarian cancer, and hematological malignancies [2] including lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia [3]. Surgery has been the first choice for cancer treatment for many centuries [1]. However, none of the available treatments alone, i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, can cure all patients. Therefore, the combination of surgery and cytostatics and/or radiation has become the standard treatment for several cancer types [1]. However, for disseminated disease involving several organs, such as metastatic solid cancer and hematological malignancies, chemotherapy remains the dominant treatment. Regrettably, for some patients, neoplastic recurrence or primary treatment resistant disease inhibits potentially curative approaches. Consequently, such patients may be offered hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

2. Purpose of the Review

Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is one of the most important cytostatics used for the treatment of several types of malignancies as well as for the conditioning prior to HSCT. It is a prodrug that is activated by several enzymes. Additionally, other important enzymes are involved in its metabolic pathway. The effect of these enzymes' genetic polymorphisms on Cy kinetics and its clinical outcomes is often contradictory and unclear. Moreover, other clinical factors may impact Cy kinetics. In this review article, we summarize the effect of different enzymes' polymorphisms on Cy kinetics and we present explanations for key Cy side effects. We also discuss the busulphan (Bu)/Cy conditioning regimen as a commonly used combination that is a clinical example of drug-drug interactions involving several polymorphic enzymes.

3. Background

3.1. Cytostatics

The classification of a cytostatic medication depends on its mechanism of action. Accordingly, these drugs may be alkylating agents, antimetabolites, antitumor antibiotics, mitosis inhibitors, topoisomerase inhibitors, enzymes, or hormonal agents.

Alkylating agents are the oldest class of drugs used in cancer treatment. They act by attaching an alkyl group to the guanine base of DNA at the imidazole ring and forming covalent bonds with amino, phosphate, and carboxyl groups. Such chemical damage can trigger apoptosis. Alkylating agents include nitrogen mustard, chlorambucil, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, thiotepa, busulphan, treosulfan, and hexamethylmelamine. They are commonly used in conditioning prior to HSCT as well as in the treatment of hematological malignancies and solid tumors such as breast adenocarcinomas, lung carcinomas, and ovarian adenocarcinomas.

3.2. Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that has been marketed since 1959 and is considered to be one of the most important drugs in cancer therapy. It is used at high doses as a part of the conditioning regimen prior to HSCT, either in combination with other cytostatics or with TBI [4–8]. Cy is also used at lower doses post-HSCT to prevent graft rejection and to decrease the severity of GVHD [9–13]. Additionally, Cy is widely used in lower doses for the treatment of hematological malignancies as well as solid tumors including ovarian adenocarcinomas, breast adenocarcinomas, small cell lung carcinomas, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, and neuroblastomas in both adults and children [14–24]. Moreover, Cy is also a potent immunosuppressive agent that affects both T- and B-lymphocytes as it is capable of attenuating both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses [25]. Due to these immunosuppressive effects, low doses of Cy are used in the treatment of several autoimmune diseases such as glomerulonephritis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjögren´s syndrome as well as in the preconditioning of hosts to prevent organ transplant rejection [26–29].

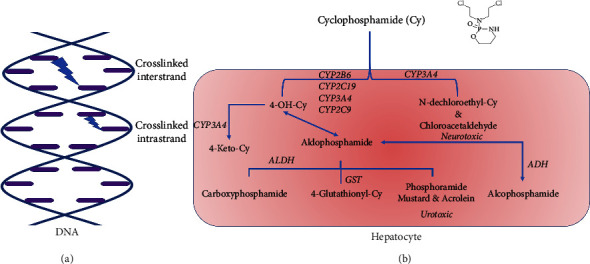

As an alkylating agent, Cy covalently binds to the guanine-N-7 base of DNA and produces DNA damage that triggers apoptosis when the cellular machinery fails in its reparative role (Figure 1(a)). It is a prodrug that has to be bioactivated to exert its effect. Alkylating agents share the Cy mechanism of action, as well as common cyclophosphamide drug-drug interactions are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Cyclophosphamide mechanism of action on DNA showing the inter- and intrastrand crosslinks that cause DNA damage and trigger apoptosis in cancer cells (a) and its metabolic pathway showing its bioactivation from a prodrug to an active agent and its terminal cytotoxic metabolites (b).

Table 1.

Common cyclophosphamide related drugs.

| Alkylating agents share the cyclophosphamide mechanism of action | Common cyclophosphamide drug-drug interactions |

|---|---|

| Nitrogen mustards: cyclophosphamide, chlormethine, uramustine, melphalan, chlorambucil, ifosfamide, bendamustine | Adalimumab, baricitinib, BCG vaccine, bupivacaine, bupivacaine liposome, certolizumab, chloroprocaine, cidofovir, cladribine, clozapine, deferiprone, dengue vaccine, deucravacitinib, etanercept, etidocaine, fingolimod, golimumab, infliximab, influenza virus vaccine, inotersen, leflunomide, levobupivacaine, lidocaine, measles virus vaccine, mepivacaine, mumps virus vaccine, nadofaragene firadenovec, nalidixic acid, natalizumab, ozanimod, poliovirus vaccine, ponesimod, prilocaine, procaine, procaine penicillin, radium 223 dichloride, ritlecitinib, ropivacaine, rotavirus vaccine, rubella virus vaccine, siponimod, smallpox vaccine, strontium-89 chloride, talimogene laherparepvec, tenofovir, teriflunomide, tetracaine, thalidomide, thiotepa, tofacitinib, typhoid vaccine, ublituximab, upadacitinib, varicella virus vaccine, voclosporin, yellow fever vaccine, zoster vaccine |

| Nitrosoureas: carmustine, lomustine, streptozocin | |

| Alkyl sulfonates: busulphan, treosulfan | |

| Platinum: cisplatin, carboplatin, dicycloplatin, eptaplatin, lobaplatin, miriplatin, nedaplatin, oxaliplatin, picoplatin, satraplatin, triplatin tetranitrate |

3.3. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

HSCT is a curative treatment for malignancies such as leukemia, lymphomas, and some solid tumors as well as for nonmalignancies including metabolic disorders and aplastic anemia [30]. However, several acute and chronic complications such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), infections, and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) are known to occur and may alter the clinical outcome.

Hematopoietic stem cells may be harvested from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood. An HSCT is performed via four main phases starting with the conditioning regimen, which aims to eliminate the malignant cells, provides a space for the donor cells, and provides enough immune suppression of the host immune system to avoid graft rejection. After conditioning, the patient receives the hematopoietic stem cells. Within a few weeks, the patient experiences the aplastic/neutropenic phase which is then followed by the postengraftment period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation phases. TBI: total body irradiation.

The conditioning regimen is one of the most important steps in HSCT. Conditioning regimens can be divided into either total body irradiation (TBI)-based TBI and cytostatics or chemotherapy-based combinations of cytostatics without TBI [31].

Radiotherapy was first used as the sole conditioning regimen. However, it was associated with many acute and chronic complications such as stomatitis, enteritis, infection-related death, and secondary leukemia post-transplantation [32]. Additionally, TBI has also been associated with late complications such as secondary malignancies, CNS damage, impaired growth, and endocrine dysfunction [33].

Development of cytostatic agents contributed to the use of cytostatics in conditioning regimens and reduced the dosage of radiotherapy. Cy was first added to TBI; however, subsequent studies in children have shown growth impairment as a late side effect [34, 35]. Later on, Bu was added with Cy, instead of TBI, since Bu has less severe delayed effects than TBI [32, 36]. The Bu/Cy regimen proved to be as good as TBI-based regimens, especially in patients with myeloid leukemia.

Nowadays, many other cytostatics are also used for conditioning prior to HSCT such as fludarabine and treosulfan [37]. Treosulfan is considered to be a less toxic alternative to Bu with a reduced incidence of acute GVHD and improved overall survival [38]. The conditioning regimen is selected with appropriate regard to the diagnosis, disease stage, patient age, patient heath status, comorbidities, and risk of transplantation-related complications.

4. Cyclophosphamide Metabolism

Cyclophosphamide is a prodrug that is metabolized mainly in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) into several metabolites. However, the predominant and active metabolite is 4-hydroxy-cyclophosphamide (4-OH-Cy) which corresponds to more than 80% of the total dose of Cy [39]. Most Cy terminal metabolites are cytotoxic substances such as 4-OH-Cy, which is degraded to phosphoramide mustard (PM) and acrolein that is responsible for urotoxicity (hemorrhagic cystitis) [40]. PM alkylates the guanine base of DNA at the N7 position of the imidazole ring and then triggers apoptosis due to the formation of guanine-adenine intrastrand crosslinks [26]. An alternative metabolic pathway involves the N-dechloroethylation of cyclophosphamide which results in an inactive metabolite, N-dechloroethyl-Cy, and a neurotoxic metabolite, chloroacetaldehyde (CA) (Figure 1(b)) [41–44].

4.1. Cytochrome P450

Cytostatics are foreign substances or xenobiotics that are metabolized by different enzymes in order to be excreted from the body. The main aim of these reactions is to make the drugs more hydrophilic and to facilitate their excretion in an aqueous medium. Most of these reactions occur successfully in the liver; however, in spite of these reactions, some drugs may be excreted unchanged.

The metabolism of cytostatics occurs in two phases. In phase I, the major reaction involved is hydroxylation, which is catalyzed mainly by CYPs. Other reactions include desulfuration, deamination, dehalogenation, epoxidation, peroxygenation, and reduction. During this phase, most of the drugs become pharmacologically less active or pharmacologically completely inactive. However, in contrast, some drugs such as cyclophosphamide are converted from an inactive prodrug to a biologically active metabolite [45].

In phase II, the compounds produced in phase I reactions, or compounds that already possess polar substituents, are converted by specific enzymes to more polar metabolites through further conjugation with polar molecules such as glutathione, glucuronic acid, and/or sulfate [45].

Cytochrome P450 enzymes are a superfamily that are mostly membrane-associated hemoproteins that can be found in the inner membrane of mitochondria or in the endoplasmic reticulum of the cells. CYPs are present in many organs, with the greatest quantity found in the liver and the small intestine. They are involved in the metabolism of many drugs and xenobiotics [46].

Most of the CYPs are inducible, which is mainly due to an increase in mRNA transcription. The administration of drugs such as phenobarbital can cause hypertrophy of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum and an increase in the amount of CYP production within a few days. Some cases of induction involve stabilization of mRNA, enzyme stabilization, or other mechanisms that affect protein translation. In contrast to the inducibility of CYPs, specific drugs can also inhibit CYP activities [47, 48].

The most common reactions catalyzed by CYPs are monooxygenase reactions. In this type of reaction, one atom of oxygen is inserted into an organic substrate, while the other oxygen atom is reduced to water:

| (1) |

CYP Phase I reactions include the metabolism of xenobiotics such as particular medicines, carcinogens, pesticides, and pollutants as well as several endogenous compounds such as steroids and fatty acids [46].

In humans, there are 57 genes and more than 58 pseudogenes for CYP production and these are divided into 18 families and 43 subfamilies [49]. Many CYPs exist in polymorphic forms that differ in their catalytic activity. This is believed to explain the interindividual variations in drug response in a given population. The most common enzymes reported to be involved in drug metabolism are CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, CYP3A4, and CYP4A11 [48, 50, 51].

Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) is the main enzyme responsible for the electron transfer from NADPH to CYP. POR is important in the metabolism of drugs and xenobiotics, and its allelic variants and variability in expression can have clinical implications [52, 53]. Cytochrome b5 is another hemoprotein that has the same function as POR.

4.2. CYP2B6 and POR Polymorphisms

Genetic polymorphism has been associated with variable levels of gene expression in the liver. Several CYP polymorphisms have been identified that possess different expression levels and hence different activities. In general, the first identified polymorphism is always known as ∗1 and is considered as the standard with respect to comparison with the other polymorphisms. In many cases, the ∗1 polymorphism may not be the most common version in humans.

CYP2B6 is the main enzyme in Cy bioactivation and is one of the common enzymes whose expression level as well as its activity is affected by genetic polymorphism [41, 54]. Other enzymes such as CYP2J2, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 are also involved in Cy metabolism [55–62].

The gene for CYP2B6 is located in the middle of chromosome 19 [63] and is mainly expressed in the liver; however, it has been detected in extrahepatic tissues such as the intestines, kidneys, brain, lungs, and skin [64–67]. CYP2B6 has been reported to be involved in the metabolism of many other drugs including ifosfamide, diazepam, and efavirenz as well as in the synthesis of endogenous compounds such as cholesterol and steroids [65, 68–70].

Several studies have shown great interindividual variation in expression and catalytic activity of CYP2B6 which may also be attributed to the genetic polymorphism of this enzyme [71–73]. Human CYP2B6 expression levels for the C1459T mutation (alleles ∗5 and ∗7) are common and known to be significantly lower than for CYP2B6∗1 [65]. In Caucasians, the SNP frequencies of A785G and G516T are 33% and 29%, respectively [65]. These SNPs are present in several CYP2B6 allelic variants such as 2B6∗4, 2B6∗6, 2B6∗7, and 2B6∗9. In the population of Pakistan, lesser allelic frequencies of 33.8% for CYP2B6∗6, 25.8% for CYP2B6∗4, and 6.5% for CYP2B6∗3 have been observed, whereas the wild-type genotype frequencies are 48.57% for CYP2B6∗6, 59.79% for CYP2B6∗4, and 90.20% for CYP2B6∗3, indicating a significant prevalence of poor metabolizers of CYP2B6, especially the ∗6 variant [74]. CYP2B6 polymorphism has been reported to affect the kinetics of several drugs. For example, after the same administered dose, the mirtazapine drug concentration was higher in patients with the CYP2B6∗6/∗6 variant [75]. Furthermore, the frequencies of different alleles vary in different populations. For example, Ribaudo et al. have shown that CYP2B6∗9 is more frequent amongst African-American individuals compared to Caucasian-American individuals, which resulted in a two-fold longer plasma half-life of efavirenz in homozygotes for this allele [76]. In total, more than fifty different alleles containing point mutations have been identified. Generally, most of these mutations are silent; however, five of them result in amino-acid substitutions in exons 1, 4, 5, and 9 [65].

As mentioned previously, POR is the main electron donor for all microsomal CYP monooxygenases. Accordingly, POR deficiency may lead to serious complications such as disordered steroidogenesis, abnormal genitalia, bone abnormalities, and William's syndrome [77–79]. POR polymorphisms have been shown to affect CYP-mediated drug metabolism as well as causing direct bioactivation of prodrugs [80]. POR polymorphisms affect the amount of enzyme produced which may affect the activities of cytochrome P450 enzymes such as CYP1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4, and 3A5 [81–84], especially for compounds which are rapidly metabolized and where the electron transfer from NADPH via POR can be rate-limiting. Our literature review indicates that POR∗28 is the only polymorphism reported to increase CYP activity in vivo [85]. Many other polymorphisms are known to decrease its activity in vivo, particularly POR∗2, 3, 4, and 5.

Chen et al. studied the effect of the POR genotype on CYP2B6 bupropion metabolism. Their results showed up to a 74% reduction in CYP2B6 activity with certain POR polymorphisms in vitro [86]. Subsequent research confirmed these findings and reported that S-mephenytoin N-demethylation by CYP2B6 varied with the specific POR polymorphism present in human livers [86, 87].

POR variability also affects CYPs other than CYP2B6, such as CYP2C9 activity when incubated with flurbiprofen, diclofenac, and/or tolbutamide. These drugs, like Cy, are metabolized rapidly [83]. The effect of POR variants and their expression levels varies with the substrate and the CYP enzyme variant; for example, POR polymorphic variants A287P and/or R457H are associated with no detectable CYP2D6 metabolism of 7-ethoxymethoxy-3-cyanocoumarin (EOMCC), while the Q153R polymorphism increased CYP2D6 activity against EOMCC in vitro [82].

Steroidogenic activity is dependent mainly on CYP1A2 and CYP2C19. POR variants affected the activities of these enzymes to different extents. POR polymorphisms A287P and/or R457H have reduced CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 catalytic activities against EOMCC. The A503V polymorphism demonstrated 85% of the wild-type activity with CYP1A2 and 113% of the wild-type activity with CYP2C19, while Q153R polymorphism increased both CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 activities [81].

CYP3A4 completely lost its ability to metabolize testosterone in vitro in two of the POR polymorphisms, Y181D and A287P. Other POR polymorphisms, such as K49N, A115V, and G413S, resulted in an up to 65% increase in CYP3A4 activity on a testosterone substrate [86]. Moreover, tacrolimus is metabolized mainly by CYP3A5; in individuals with POR∗28 polymorphism, tacrolimus exposure was significantly decreased [84].

A study of human liver samples showed that four POR polymorphisms (K49N, L420M, A503V, and L577P) were associated with reductions in both POR and in drug-metabolizing CYP activities. The same study also showed intronic polymorphisms that altered POR activity [88].

4.3. The Effect of CYPs and POR Polymorphisms and Their Expression Levels on Cyclophosphamide Pharmacokinetics

Several studies have investigated the clinical efficacy of Cy alone or in combination with other cytostatics or radiotherapy [5, 89] Studies on Cy kinetics have shown a high interindividual variation in elimination half-life and clearance which then affects treatment efficacy and toxicity [41, 44, 90]. This variation may be explained by polymorphisms in CYP2B6, the main enzyme responsible for the conversion of Cy to its active form, 4-OH-Cy in the liver [44, 54, 71–73, 91–93].

This variability has been attributed to polymorphisms in the CYP2B6 gene, such as CYP2B6∗4, CYP2B6∗6, CYP2B6∗7, and CYP2B6∗9 [57, 73, 94–97]. Common alleles were reported to affect Cy kinetics by either decreased liver protein expression or altered function of the enzyme. These alleles include CYP2B6∗2 (C64T, R22C), CYP2B6∗4 (A785G, S262R), CYP2B6∗5 (C1459T, R487C), CYP2B6∗6 (G516T, Q172H and A785G, K262R), CYP2B6∗7 (G516T, Q172H; A785G, K262R; and C1459T, R487C), and CYP2B6∗9 (Q172H) [65, 95, 98–101]. CYP2B6rs2279343 was reported to be associated with improved survival of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma Cy treated patients [102]. Barnett et al. suggested that the effect of CYP2B6 and CYP2C9 on Cy clearance is more significant in children less than two years of age, as compared to older children [103]. In addition, some more rare SNPs have been reported to result in absent or nonfunctional enzymes [104].

On the other hand, other studies have concluded that CYP polymorphisms (including CYP2B6) do not play a significant role in the response variation to Cy with respect to complete remission, while clinical factors such as patients' ages and cancer grades may be more significant [54–56, 105–109]. Recently, a lack of association of CYP2B6 pharmacogenetics with Cy toxicity in patients was reported; moreover, aldehyde dehydrogenases 1A1 (ALDH1A1) rs8187996 may have a lower risk of Cy toxicity compared to wild-type patients [110]. In pediatric patients with non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphomas, the CYP2B6 genotype was reported to influence Cy but had no clear impact on the clinical outcome [111].

As mentioned previously, other enzymes such as CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2J2 were reported to be involved in Cy bioactivation but to a lesser extent [18, 51, 55, 56, 59, 60, 92, 100, 101, 112, 113]. Cy-treated patients with the variant CYP2C9 had an increased risk of leukopenia but responded better to treatment compared to those who were carriers of wild-type CYP2C9 [114].

The expression levels of C1459T mutation (alleles ∗5 and ∗7) of CYP2B6 are significantly lower than for CYP2B6∗1 [65], and this leads to a higher Cy intrinsic clearance both in vitro and in vivo for the latter [90, 95]. Additionally, a higher activity of CYP2B6∗6 was reported in Cy bioactivation in comparison with a decreased activity of efavirenz bioactivation. In this in vitro study, the tested microsomes contained CYP2B6.1, CYP2B6.4, or CYP2B6.6 but with the same POR activity and POR/CYP ratio in each batch [99].

The formation of 4-OH-Cy is a fast reaction which means that the rate-limiting step may be the electron transfer from the POR to CYP [88] (Figure 3(a)). In an in vitro experiment with recombinant human CYP2B6.1, the intrinsic clearance of Cy was clearly proportional to the POR/CYP ratio despite the Km being almost constant in all batches, confirming a good positive linear correlation between Cy clearance and the POR/CYP ratio [115]. Additionally, results obtained from POR gene expression measurements in patients conditioned with Cy showed significant POR up-regulation after Cy infusion, with high interindividual variations in gene expression. Still, POR expression showed a significant positive correlation with the concentration ratio 4-OH-Cy/Cy. In those patients, some were carriers for POR∗28; however, others also had high POR expression, possibly due to other POR polymorphisms not yet described or effects on nuclear receptors or other factors involved in POR regulation, also resulting in higher inducibility [115]. In summary, (i) CYPs are therapeutically important and (ii) polymorphisms affecting POR expression or activity should be considered for dose adjustment in order to achieve optimal therapeutic drug plasma concentrations. The most important enzymes involved in the cyclophosphamide metabolic pathway and the most common polymorphisms affecting its kinetics are listed in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Possible causes of variation in cyclophosphamide kinetics. (a) The different POR enzyme polymorphisms and expression levels that can affect the drug bioactivation. (b) Sequence of administration - cyclophosphamide administration after busulphan since several enzymes are involved in both drugs' metabolic pathways. Bu: busulphan; Cy: cyclophosphamide; CYP: cytochrome P450; GST: glutathione S-transferase; POR: cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase; THT: tetrahydrothiophene.

Table 2.

Summary of the enzymes involved in the cyclophosphamide metabolic pathway and the most common polymorphisms affecting its kinetics.

| Enzyme family | Enzyme involved in cyclophosphamide metabolic pathway | Polymorphisms affecting cyclophosphamide kinetics | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH) | ALDH1A1 | ∗ 2, rs8187996 | Hassan et al. [112] |

| Kalra et al. [60] | |||

| Helsby et al. [57] | |||

| Hwang et al. [110] | |||

| ALDH3A1 | ∗ 2 | Afsar et al. [55] | |

| Ming et al. [96] | |||

|

| |||

| Cytochrome P450 (CYP) | CYP2B6 | ∗ 2, ∗ 4, ∗ 5, ∗ 6, ∗ 7, ∗ 8, ∗ 9 | Raccor et al. [54] |

| Hassan et al. [112] | |||

| Labib et al. [102] | |||

| Shu et al. [101] | |||

| Ming et al. [96] | |||

| Helsby et al. [101] | |||

| CYP2C9 | Hassan et al. [112] | ||

| Schirmer et al. [114] | |||

| CYP2C19 | ∗ 2, ∗ 17 | Afsar et al. [55] | |

| Jamieson et al. [108] | |||

| Shu et al. [101] | |||

| Kalra et al. [60] | |||

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

| Helsby et al. [101] | |||

| CYP2D6 | Hassan et al. [112] | ||

| Cura et al. [153] | |||

| CYP2J2 | ∗ 7, rs1056596 | El-Serafi et al. [115] | |

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

| CYP3A4 | Hassan et al. [112] | ||

| Kumaraswami et al. [62] | |||

| CYP3A5 | ∗ 3 | Hassan et al. [112] | |

| Kumaraswami et al. [62] | |||

| Shu et al. [101] | |||

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

|

| |||

| Glutathione S-transferase (GST) | GSTA1 | ∗ B | Afsar et al. [55] |

| Hassan et al. [112] | |||

| GSTP1 | rs1695 | Hassan et al. [112] | |

| Kumaraswami et al. [62] | |||

| Attia et al. [154] | |||

| Cura et al. [153] | |||

| Hajdinak et al. [155] | |||

|

| |||

| Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) | POR | ∗ 28 | El-Serafi et al. [115] |

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

Italic values indicate a genetic polymorphism.

4.4. The Role of CYP2J2 in Cyclophosphamide Extrahepatic Bioactivation

CYP2J2 is another CYP involved in the metabolism of xenobiotics. It is encoded by the CYP2J2 gene which has been mapped to the short arm of chromosome 1 in humans and chromosome 4 in mice [116].

CYP2J2 is active mainly in the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems [117–119]. CYP2J2 has been reported to metabolize several drugs, particularly in extrahepatic tissues [119–121]. High CYP2J2 activity in the intestines could contribute to the first-pass metabolism of some drugs [120–122]. Moreover, CYP2J2 is dominant in the presystemic elimination of astemizole in human and rabbit small intestines [121].

In the human heart, CYP2J2 is responsible for the epoxidation of endogenous arachidonic acid to four regioisomeric epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) released in response to certain stimuli such as ischemia [123]. Transgenic mice overexpressing CYP2J2 have been shown to have less extensive infarctions and more complete recovery after ischemia [124–126]. These mice were also better protected against global cerebral ischemia associated with increased regional cerebral blood flow [127].

Additionally, CYP2J2 has been also associated with malignancy as it is highly expressed in cells of hematological and solid tumors [128–135]. Chen et al. have reported that CYP2J2 is highly expressed in human- and mouse-derived malignant hematological cell lines (K562, HL-60, Raji, MOLT-4, SP2/0, Jurkat, and EL4 cells) as well as in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells of leukemic patients [130]. In these patients, a high level of expression of CYP2J2 was associated with accelerated neoplastic proliferation and attenuated apoptosis. CYP2J2 overexpression also enhanced malignant xenograft growth [130].

CYP2J2 is also overexpressed in ovarian cancer and lung cancer metastases [131, 133], and its inhibition by terfenadine-related compounds has been shown to suppress the proliferation of human cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo, which implies that CYP2J2 expression is part of a protective mechanism for cancer cell survival. CYP2J2 inhibition has been shown to suppress the proliferation of cancer cells [129]. The expression of CYP2J2 in HL-60 cells can account for the Cy cytotoxic effects in these cells [136]. HL-60 cells predominantly express CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 but not CYP2B6; however, neither was previously reported to be involved in Cy bioactivation [136, 137].

Interestingly, CYP2J2 has been reported to be involved in the bioactivation of Cy [58, 59]. A previous study has shown that Cy treatment upregulated the expression of CYP2J2; however, the interindividual variation was substantial. For example, Cy-treated patients who were carriers of CYP2J2 SNP “rs1056596” (A/T) demonstrated low CYP2J2 expression [59]. Despite the high variability, the expression of CYP2J2 was significantly correlated with the bioactivation of Cy as expressed by the concentration ratio of 4-OH-Cy/Cy [59, 138]. In addition, the inhibition of CYP2J2 in HL-60 cells reduced 4-OH-Cy formation and concomitantly increased the cell viability, which supports the role of CYP2J2 in Cy bioactivation [130]. In the Ethiopian population, it was reported that patients carrying the CYP2J2∗7 allele with low baseline blood counts were at a higher risk for chemotherapy-induced hematologic toxicities [58]. In some populations, the ratio Vmax/Km (Vmax is the maximum velocity of the reaction where all the enzymes are saturated with the substrate, while Km is the concentration of the substrate at which half of the maximum velocity is achieved) for CYP2J2 was higher compared to that obtained for CYP2B6 [139]. This suggests that CYP2J2 may be the enzyme predominantly responsible for Cy bioactivation in these patients and not CYP2B6 as described earlier [7, 10].

The abovementioned reports underline the importance of CYP2J2's role in Cy bioactivation and its involvement in drug-related toxicities, especially in organ specific toxicities where CYP2J2 is highly expressed. The urinary bladder, heart, and intestines are subject to these considerations. Hemorrhagic cystitis as well as the alteration of intestinal permeability accompanying diarrhea (as a marker of intestinal barrier dysfunction) were common side effects that were observed following treatment with Cy in several patients [40, 139–141]. High doses of Cy were reported to be correlated with acute cardiac toxicity resulting in heart failure or a decrease in systolic function [142]. In addition, it has also been shown that damage to the endothelial cells in the mesenteric artery was correlated with Cy treatment [143, 144].

Finally, drugs metabolized via CYP2J2 and concomitantly used during Cy conditioning may alter Cy kinetics and hence the treatment efficacy and increase the Cy-related toxicities. This may explain some of the major side effects reported after HSCT.

4.5. Glutathione Importance in Cyclophosphamide Metabolism

Glutathione (GSH) is a nonessential tripeptide that has an unusual peptide linkage between the amino group of cysteine and the carboxyl group of the glutamate side chain. The sulfhydryl (thiol) group (SH) of cysteine serves as a proton donor and is responsible for the biological activity of glutathione.

Glutathione exists in reduced and oxidized states. In the reduced state, the thiol group of cysteine is able to donate a reducing equivalent (H+ + e−) to other unstable molecules. This reaction converts the glutathione into its active form that can react with another reactive glutathione to form a dimer glutathione disulfide (GSSG). It is important to have a high concentration of glutathione in cells for this reaction to occur. The reaction is often catalyzed by glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) which are present mainly in the cytosol of liver cells. GSH can be regenerated from GSSG by the enzyme glutathione reductase [145].

GSH is the major endogenous antioxidant. Additionally, it has an important role in the conjugation of drugs and other xenobiotics as well as in maintaining exogenous antioxidants such as vitamins C and E in their reduced (active) forms. GSH also plays a major role in several biochemical reactions such as DNA synthesis and repair, protein synthesis, amino-acid transport, and enzyme activation [146].

GSH is very important for Cy metabolism. As mentioned previously, Cy end-metabolites such as acrolein and PM are cytotoxic. These metabolites are responsible for the urotoxicity and cardiotoxicity reported in patients treated with Cy [41–44]. GSH reacts with the active metabolite, 4-OH-Cy, as well as its toxic metabolite, acrolein [147, 148]. Acrolein is highly toxic when administered to perfused rat hearts, isolated coronary blood vessels, or incubated with cardiac myocytes and isolated cardiac mitochondria [149–151].

In Cy treated patients, acrolein is metabolized and detoxified by GSTP via conjugation with GSH. In the absence of GSH, acrolein reacts with circulating and cardiac proteins to form protein-acrolein adducts that may contribute to cardiac injury and cardiotoxicity [148]. Such knowledge can be very valuable for patients with certain GSTP1 polymorphisms that were reported to alter function and increases the risk of Cy-toxicities [152–156].

Additionally, GSTP was reported as a protective agent against endothelial dysfunction as well as Cy-induced urotoxicity and cardiotoxicity [62, 148, 157, 158].

4.6. The Importance of Epigenetics in Drug Metabolism

Recently, epigenetic mechanisms have been reported to be important in drug treatment [159]. Epigenetic modifiers contribute to the interindividual variations in drug metabolism. A novel class of drugs, termed epidrugs, has been reported from clinical trials to intervene in the epigenetic control of gene expression. Furthermore, epigenetic biomarkers can be used in monitoring patients' disease prognosis and treatment.

5. Busulphan/Cyclophosphamide as a Common Conditioning Regimen

Busulphan/cyclophosphamide has been one of the most commonly used conditioning regimens in the clinical setting in recent decades [160]. Busulphan is predominantly metabolized via conjugation with GSH [161–164] that is catalyzed by GSTA1 [112, 165, 166]. The conjugation of Bu with glutathione results in the formation of a sulfonium ion which is unstable and decomposes to tetrahydrothiophene (THT) and an N-acetyl-cysteine sulfonium ion. THT is oxidized to THT 1-oxide that is further oxidized to sulfolane and finally to 3-hydroxy sulfolan [161–164]. Other hepatic enzymes, including flavin-containing mono-oxygenase-3 (FMO3) and CYPs, are involved in Bu metabolism and affect its kinetics [167, 168]. FMO3, along with several CYPs, is involved in THT oxidation to THT-1 oxide and probably the subsequent oxidation steps [168]. Accordingly, drugs metabolized via CYPs such as Cy are known to affect Bu plasma concentrations and kinetics [168–171].

GSH is also an important enzyme in 4-OH-Cy detoxification [42, 43]. As previously mentioned, Bu consumes up to 60% of hepatic GSH [172]. It is believed that the accumulation of the cytotoxic 4-OH-Cy due to GSH consumption by Bu may cause hepatic damage and increase the incidence of SOS [147] (Figure 3(b)). The time interval between the last Bu dose and the first Cy-dose is important in the development of SOS. A significantly lower incidence of SOS was found when this time interval was >24 hours compared to that seen when the interval was 12 hours [147, 160]. Furthermore, reversal of the administration order from Bu and then Cy to Cy and then Bu produced the same engraftment outcome but reduced the toxicity and improved the mortality of the conditioning regimen both in patients and mice [173–176]. Based on all of the above discussion, Bu/Cy conditioning protocols should be revised to take the drug administration sequence, and/or time interval between both drugs, into account in addition to considering the appropriate accompanying supportive therapy.

6. Opinion and Future Perspectives

In this review, we have summarized the most important studies investigating the effect of Cy pharmacogenomics on its kinetics. We have discussed the important older studies as well as the most recent research. Additionally, as well as focusing on CYP2B6, we have expanded our review to include the other important enzymes affecting Cy kinetics. We indicated the importance of enzymes such as CYP2C19, CYP2J2, POR, and GSTA1. Finally, we have discussed Bu/Cy conditioning as a clinical example of drug interactions that can be affected by the enzymes' polymorphisms.

Based on our review, it is evident that the CYP polymorphisms CYP2B6, CYP2C19, and POR change the Cy kinetics and hence change the clinical outcome. However, such an effect is complex and is clearly multifactorial. In some patients, the induction of other enzymes involved in Cy bioactivation may mask this effect.

Additionally, concomitant medications given during Cy treatment may induce (or suppress) particular CYPs and alter the Cy bioactivation. Such induction/suppression can be very variable and polymorphism dependent. Finally, a patient's age and clinical circumstances may play an important role in Cy's effect on the clinical outcome.

Currently, the most commonly used method for personalized treatment is therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) which starts after the patient's first dose. However, the application of TDM can be challenging because of its timing limitations, usually occurring late in the evening or at night. Additionally, TDM increases the work load on the nurses since they have to collect and process several blood samples after the end of the Cy infusion (Figure 4(a)). An alternative TDM strategy is a limited sampling model (LSM) which requires fewer blood samples to be taken (2–4 samples compared to 8–10 samples). However, it is still stressful to run the samples, obtain the results, then calculate the drug kinetics, and adjust the dose before the next infusion is required. Our review indicates that there is a lack of reliable LSMs for Cy kinetics calculations.

Figure 4.

Cyclophosphamide personalized dose adjustment based on the currently available therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) (a) and applying gene sequencing in the future (b).

We believe that in the future, a patient's gene sequencing will be one of the routine investigations prior to the start of Cy treatment (Figure 4(b)). Gene sequencing results should be closely interpreted in order to understand the possible interactions between different enzymes' polymorphisms. Such investigations are of great importance, especially in some populations where specific polymorphisms are known to be common and can alter the Cy kinetics. Finally, accompanying treatment as well as Cy in combination with other cytostatics should be considered by the clinician in order to avoid drug interactions that may impact the clinical outcome. Examples of such scenarios are presented in Table 3. Taken together, we hope that this summary will help in facilitating personalized cyclophosphamide dose adjustment, reducing associated adverse side effects, and improving clinical outcomes.

Table 3.

Common examples of clinical scenarios that may occur during cyclophosphamide treatment.

| Condition | Complication | Possible cause(s) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cy infusion | High cy blood levels | CYP2B6 polymorphism | Hassan et al. [112] |

| Shu et al. [101] | |||

| Ming et al. [96] | |||

| Helsby et al. [101] | |||

| Drug-drug interactions | Hassan et al. [112] | ||

| Conklin et al. [148] | |||

| Cura et al. [153] | |||

| Low cy blood levels | POR∗28 polymorphism | El-Serafi et al. [115] | |

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

| Extrahepatic side effects | CYP2J2 polymorphism(s) | El-Serafi et al. [115] | |

| Ahmed et al. [58] | |||

|

| |||

| Bu-cy conditioning | High cy blood levels | GSH/CYPs consumption by bu | Hassan et al. [112] |

| Kumaraswami et al. [62] | |||

| Cura et al. [153] | |||

| Hajdinák et al. [155] | |||

Bu: busulphan; Cy: cyclophosphamide; CYP: cytochrome P450; GSH: glutathione; POR: cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase.

7. Conclusion

Cyclophosphamide is a prodrug that is mainly bioactivated by CYP2B6. However, several other CYPs are involved in its bioactivation. The rate of bioactivation is controlled by the POR enzyme which can alter this step and markedly affect the drug kinetics. Additionally, other enzymes such as GSH/GST are also involved in the Cy metabolic pathway. The involvement of CYP2J2 in Cy metabolism can cause extrahepatic bioactivation and hence several side effects. The effect of any of the previous enzymes' polymorphisms on Cy kinetics and the clinical outcome have been extensively investigated; however, the picture here is still complex. In several studies, enzyme polymorphisms such as CYP2B6, CYP2C19, GSTA1, and POR were reported to alter the drug kinetics as well as the clinical outcome. However, other factors such as the patient's age, diagnosis, and clinical status could also alter Cy kinetics.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Ajman University, UAE, for their support for the APC.

Data Availability

No data were used to support the findings of this study.

Additional Points

What Is Already Known about This Subject. Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is a prodrug that is activated predominantly by CYP2B6. There is a high interindividual variation in Cy kinetics that can be accounted for by CYP2B6 polymorphisms and/or other clinical factors. What This Review Adds. Enzyme polymorphisms alter Cy kinetics. However, such an effect is multifactorial as contributions from CYP2B6, other CYPs, and GSTs as well as POR polymorphisms may occur. The clinical factors (age, diagnosis, etc.) may mask the effect of these polymorphisms. Patient gene sequencing prior to the start of Cy treatment will certainly help in personalizing the most appropriate Cy dose and hence improve the clinical outcome.

Disclosure

A preprint has previously been published: Ibrahim El-Serafi, Sinclair Steele. Cyclophosphamide pharmacogenomics and their effect on its bioactivation and pharmacokinetics. Authorea. Aug 18, 2023. DOI: 10.22541/au.169232953.37091454/v1 [177].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sudhakar A. History of cancer, ancient and modern treatment methods. Journal of Cancer Science and Therapy . 2009;1(2):1–4. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.100000e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chizuka A., Suda M., Shibata T., et al. Difference between hematological malignancy and solid tumor research articles published in four major medical journals. Leukemia . 2006;20(10):1655–1657. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabattini E., Bacci F., Sagramoso C., Pileri S. A. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica . 2010;102(3):83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondo N., Takahashi A., Ono K., Ohnishi T. DNA damage induced by alkylating agents and repair pathways. Journal of Nucleic Acids . 2010;2010(1):18. doi: 10.4061/2010/543531.543531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds M., McCann S. R. A comparison between regimens containing chemotherapy alone (busulfan and cyclophosphamide) and chemotherapy (V. RAPID) plus total body irradiation on marrow engraftment following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. European Journal of Haematology . 1989;43(4):314–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1989.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi T., Pearson R., Cao Q., et al. Effects of cyclophosphamide related genetic variants on clinical outcomes of adult hematopoietic cell transplant patients. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology . 2022;89(4):543–549. doi: 10.1007/s00280-021-04389-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavacchi D., Landini I., Perrone G., Roviello G., Mini E., Nobili S. Pharmacogenetics in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP: still an unmet challenge. Pharmacology and Therapeutics . 2022;229 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107924.107924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben Hassine K., Powys M., Svec P., et al. Total body irradiation forever? Optimising chemotherapeutic options for irradiation-free conditioning for paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Frontiers in Pediatrics . 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.775485.775485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luznik L., Fuchs E. J. High-dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide to promote graft-host tolerance after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunologic Research . 2010;47(1-3):65–77. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jullien M., Guillaume T., Le Bourgeois A., et al. Phase I study of zoledronic acid combined with escalated doses of interleukine 2 for early in vivo generation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells after haploidentical stem cell transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide. American Journal of Hematology . 2024;99(3):350–359. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruyama Y., Nishikii H., Kurita N., et al. Impact of CD34 positive cell dose in donor graft on the outcomes after haploidentical peripheral blood stem cell transplantation with post-transplant cyclophosphamide-A retrospective single-center study with a Japanese cohort. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases . 2024;105 doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2023.102820.102820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakaya Y., Nakamae H., Nishikubo M., et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation using HLA-haploidentical donor with post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus HLA-matched sibling donor for lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplantation . 2024;59(5):630–636. doi: 10.1038/s41409-024-02229-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kachur PharmD Bcop E., N Patel PharmD Bcop Cpp J., L Morse PharmD Bcop A., C Moore PharmD Bcps Bcop Dpla Fccp D., R Arnall PharmD Bcop J. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide for the prevention of graft-vs.-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a guide to management for the advanced practitioner. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology . 2023;14(6):520–532. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2023.14.6.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charo L. M., Homer M. V., Natarajan L., et al. Drug metabolising enzyme polymorphisms and chemotherapy-related ovarian failure in young breast cancer survivors. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology . 2021;41(3):447–452. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2020.1754369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thrope A., Gerber L. M., Thomas C., Antal Z. Longitudinal assessment of Leydig cell function in male survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer . 2024;71(3) doi: 10.1002/pbc.30829.e30829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J. L., Gerrie A. S., Savage K. J., et al. Frontline therapy with bendamustine rituximab (BR) and rituximab cyclophosphamide vincristine prednisone (RCVP) confers similar long-term outcomes in patients with treatment naive Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia in a real-world setting: a population-based analysis. Leukemia and Lymphoma . 2024;65(3):346–352. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2023.2290466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albogami S. M., Asiri Y., Asiri A., Alnefaie A. A., Alnefaie S. Effects of neoadjuvant therapies on genetic regulation of targeted pathways in ER+ primary ductal breast carcinoma: a meta-analysis of microarray datasets. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal . 2021;29(7):656–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S., Yang J., Fu F., et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for the prediction of hepatotoxicity induced by a docetaxel, epirubicin and Cyclophosphamidegimen in breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics . 2021;22(2):87–98. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2020-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camus V., Thieblemont C., Gaulard P., et al. Prednisone in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the ro-CHOP trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology . 2024;25 doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.01687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn I. E., Brander D. M., Ren Y., et al. Five-year follow-up of a phase 2 study of ibrutinib plus fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy in CLL. Blood Advances . 2024;8(4):832–841. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023011574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pusztai L., Denkert C., O’Shaughnessy J., et al. Event-free survival by residual cancer burden with pembrolizumab in early-stage TNBC: exploratory analysis from KEYNOTE-522. Annals of Oncology . 2024;35(5):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2024.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albain K. S., Yau C., Petricoin E. F., et al. Neoadjuvant trebananib plus paclitaxel-based chemotherapy for stage II/III breast cancer in the adaptively randomized I-SPY2 trial-efficacy and biomarker discovery. Clinical Cancer Research . 2024;30(4):729–740. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reni M., Peretti U., Macchini M., et al. Cyclophosphamide maintenance to extend combination chemotherapy-free interval in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Digestive and Liver Disease . 2024;56(3):509–513. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2023.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Short N. J., Jabbour E., Jain N., et al. A phase 1/2 study of mini-hyper-CVD plus venetoclax in patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Advances . 2024;8(4):909–915. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023012231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daleboudt G. M., Reinders M. E., Hartigh J. d., et al. Concentration-controlled treatment of lupus nephritis with mycophenolate mofetil. Lupus . 2013;22(2):171–179. doi: 10.1177/0961203312469261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binotto G., Trentin L., Semenzato G. Ifosfamide and cyclophosphamide: effects on immunosurveillance. Oncology . 2003;65(2):17–20. doi: 10.1159/000073353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woon T. H., Tan M. J. H., Kwan Y. H., Fong W. Evidence of the interactions between immunosuppressive drugs used in autoimmune rheumatic diseases and Chinese herbal medicine: a scoping review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine . 2024;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2024.103017.103017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tekeoglu S., Temiz Karadag D., Ozdemir Isik O., Yazici A., Cefle A. Analysis of clinical, immunological characteristics, damage, and survival in 300 Turkish systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus . 2024;33(3):298–311. doi: 10.1177/09612033241228174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsch S., Pohler G. H., Seeliger B., Prasse A., Witte T., Thiele T. Treatment strategies in MDA5-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis: a single-center retrospective analysis. Clinical and Experimental Medicine . 2024;24(1):p. 37. doi: 10.1007/s10238-024-01300-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riley R. S., Idowu M., Chesney A., et al. Hematologic aspects of myeloablative therapy and bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis . 2005;19(2):47–79. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burt R. K., Loh Y., Pearce W., et al. Clinical applications of blood-derived and marrow-derived stem cells for nonmalignant diseases. JAMA . 2008;299(8):925–936. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Copelan E. A., Deeg H. J. Conditioning for allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with lymphohematopoietic malignancies without the use of total body irradiation. Blood . 1992;80(7):1648–1658. doi: 10.1182/blood.v80.7.1648.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joachim Deeg H. Delayed complications and long-term effects after bone marrow transplantation. Hematology-Oncology Clinics of North America . 1990;4(3):641–657. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(18)30483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta T., Kannan S., Dantkale V., Laskar S. Cyclophosphamide plus total body irradiation compared with busulfan plus cyclophosphamide as a conditioning regimen prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy . 2011;4(1):17–29. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wingard J. R., Plotnick L. P., Freemer C. S., et al. Growth in children after bone marrow transplantation: busulfan plus cyclophosphamide versus cyclophosphamide plus total body irradiation. Blood . 1992;79(4):1068–1073. doi: 10.1182/blood.v79.4.1068.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters W. P., Henner W. D., Grochow L. B., et al. Clinical and pharmacologic effects of high dose single agent busulfan with autologous bone marrow support in the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Research . 1987;47(23):6402–6406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remberger M., Torlen J., Serafi I. E., et al. Toxicological effects of fludarabine and treosulfan conditioning before allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. International Journal of Hematology . 2017;106(4):471–475. doi: 10.1007/s12185-017-2320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu S., Liu G., Liu J., Chen Q., Wang Z. Long-Term outcomes of treosulfan-vs. Busulfan-based conditioning regimen for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia before hematopoietic cell transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers Oncology . 2020;10 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.591363.591363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sladek N. E. Metabolism of oxazaphosphorines. Pharmacology and Therapeutics . 1988;37(3):301–355. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(88)90004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao J., Chen Y., Zhang X., et al. Slightly photo-crosslinked chitosan/silk fibroin hydrogel adhesives with hemostasis and anti-inflammation for pro-healing cyclophosphamide-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Materials Today Bio . 2024;25 doi: 10.1016/j.mtbio.2024.100947.100947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho J. Y., Lim H. S., Chung J. Y., et al. Haplotype structure and allele frequencies of CYP2B6 in a Korean population. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2004;32(12):1341–1344. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang T. K., Weber G. F., Crespi C. L., Waxman D. J. Differential activation of cyclophosphamide and ifosphamide by cytochromes P-450 2B and 3A in human liver microsomes. Cancer Research . 1993;53(23):5629–5637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren S., Yang J. S., Kalhorn T. F., Slattery J. T. Oxidation of cyclophosphamide to 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and deschloroethylcyclophosphamide in human liver microsomes. Cancer Research . 1997;57(19):4229–4235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho J. Y., Lim H. S., Chung J. Y., et al. Haplotype structure and allele frequencies of CYP2B6 in a Korean population. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2004;32(12):1341–1344. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guengerich F. P. Common and uncommon cytochrome P450 reactions related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chemical Research in Toxicology . 2001;14(6):611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez-Antona C., Ingelman-Sundberg M. Cytochrome P450 pharmacogenetics and cancer. Oncogene . 2006;25(11):1679–1691. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guengerich F. P. Cytochrome p450 and chemical toxicology. Chemical Research in Toxicology . 2008;21(1):70–83. doi: 10.1021/tx700079z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans W. E., Johnson J. A. Pharmacogenomics: the inherited basis for interindividual differences in drug response. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics . 2001;2(1):9–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson D. R., Zeldin D. C., Hoffman S. M., Maltais L. J., Wain H. M., Nebert D. W. Comparison of cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes from the mouse and human genomes, including nomenclature recommendations for genes, pseudogenes and alternative-splice variants. Pharmacogenetics . 2004;14(1):1–18. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falduto A., Cimino F., Speciale A., et al. How gene polymorphisms can influence clinical response and toxicity following R-CHOP therapy in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Blood Reviews . 2017;31(4):235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mlakar V., Huezo-Diaz Curtis P., Satyanarayana Uppugunduri C. R., Krajinovic M., Ansari M. Pharmacogenomics in pediatric oncology: review of gene-drug associations for clinical use. International Journal of Molecular Sciences . 2016;17(9):p. 1502. doi: 10.3390/ijms17091502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S. L., Han J. F., He X. Y., Wang X. R., Hong J. Y. Genetic variation of human cytochrome p450 reductase as a potential biomarker for mitomycin C-induced cytotoxicity. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2007;35(1):176–179. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pandey A. V., Fluck C. E., Mullis P. E. Altered heme catabolism by heme oxygenase-1 caused by mutations in human NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2010;400(3):374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raccor B. S., Claessens A. J., Dinh J. C., et al. Potential contribution of cytochrome P450 2B6 to hepatic 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide formation in vitro and in vivo. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2012;40(1):54–63. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afsar N. A., Ufer M., Haenisch S., et al. Relationship of drug metabolizing enzyme genotype to plasma levels as well as myelotoxicity of cyclophosphamide in breast cancer patients. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2012;68(4):389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandes B. J., Miranda Silva C. D., Andrade J. M., Matthes Â. D. C. S., Coelho E. B., Lanchote V. L. Pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide enantiomers in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology . 2011;68(4):897–904. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1554-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helsby N. A., Yong M., van Kan M., de Zoysa J. R., Burns K. E. The importance of both CYP2C19 and CYP2B6 germline variations in cyclophosphamide pharmacokinetics and clinical outcomes. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2019;85(9):1925–1934. doi: 10.1111/bcp.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmed J. H., Makonnen E., Yimer G., et al. CYP2J2(∗)7 genotype predicts risk of chemotherapy-induced hematologic toxicity and reduced relative dose intensity in Ethiopian breast cancer patients. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2019;10:p. 481. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El-Serafi I., Fares M., Abedi-Valugerdi M., et al. Cytochrome P450 2J2, a new key enzyme in cyclophosphamide bioactivation and a potential biomarker for hematological malignancies. The Pharmacogenomics Journal . 2015;15(5):405–413. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2014.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalra S., Kaur R. P., Ludhiadch A., et al. Association of CYP2C19∗2 and ALDH1A1∗1/∗2 variants with disease outcome in breast cancer patients: results of a global screening array. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2018;74(10):1291–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00228-018-2505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tecza K., Pamula-Pilat J., Lanuszewska J., Butkiewicz D., Grzybowska E. Pharmacogenetics of toxicity of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget . 2018;9(10):9114–9136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumaraswami K., Katkam S. K., Aggarwal A., et al. Epistatic interactions among CYP2C19∗2, CYP3A4 and GSTP1 on the cyclophosphamide therapy in lupus nephritis patients. Pharmacogenomics . 2017;18(15):1401–1411. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2017-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ekins S., Wrighton S. A. The role of CYP2B6 in human xenobiotic metabolism. Drug Metabolism Reviews . 1999;31(3):719–754. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100101942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gervot L., Rochat B., Gautier J. C., et al. Human CYP2B6: expression, inducibility and catalytic activities. Pharmacogenetics . 1999;9(3):295–306. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lang T., Klein K., Fischer J., et al. Extensive genetic polymorphism in the human CYP2B6 gene with impact on expression and function in human liver. Pharmacogenetics . 2001;11(5):399–415. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miksys S., Lerman C., Shields P. G., Mash D. C., Tyndale R. F. Smoking, alcoholism and genetic polymorphisms alter CYP2B6 levels in human brain. Neuropharmacology . 2003;45(1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yengi L. G., Xiang Q., Pan J., et al. Quantitation of cytochrome P450 mRNA levels in human skin. Analytical Biochemistry . 2003;316(1):103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ward B. A., Gorski J. C., Jones D. R., Hall S. D., Flockhart D. A., Desta Z. The cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) is the main catalyst of efavirenz primary and secondary metabolism: implication for HIV/AIDS therapy and utility of efavirenz as a substrate marker of CYP2B6 catalytic activity. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics . 2003;306(1):287–300. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zanger U. M., Klein K. Pharmacogenetics of cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6): advances on polymorphisms, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Frontiers in Genetics . 2013;4:p. 24. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe T., Saito T., Rico E. M. G., et al. Functional characterization of 40 CYP2B6 allelic variants by assessing efavirenz 8-hydroxylation. Biochemical Pharmacology . 2018;156:420–430. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klein K., Lang T., Saussele T., et al. Genetic variability of CYP2B6 in populations of African and Asian origin: allele frequencies, novel functional variants, and possible implications for anti-HIV therapy with efavirenz. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2005;15(12):861–873. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rotger M., Colombo S., Furrer H., et al. Influence of CYP2B6 polymorphism on plasma and intracellular concentrations and toxicity of efavirenz and nevirapine in HIV-infected patients. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2005;15(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsuchiya K., Gatanaga H., Tachikawa N., et al. Homozygous CYP2B6 ∗6 (Q172H and K262R) correlates with high plasma efavirenz concentrations in HIV-1 patients treated with standard efavirenz-containing regimens. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications . 2004;319(4):1322–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ahmed S., Khan S., Janjua K., Imran I., Khan A. U. Allelic and genotype frequencies of major CYP2B6 polymorphisms in the Pakistani population. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine . 2021;9(3):p. e1527. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sirot E. J., Harenberg S., Vandel P., et al. Multicenter study on the clinical effectiveness, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacogenetics of mirtazapine in depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology . 2012;32(5):622–629. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e3182664d98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ribaudo H. J., Haas D. W., Tierney C., et al. Pharmacogenetics of plasma efavirenz exposure after treatment discontinuation: an adult AIDS clinical trials group study. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2006;42(3):401–407. doi: 10.1086/499364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fluck C. E., Tajima T., Pandey A. V., et al. Mutant P450 oxidoreductase causes disordered steroidogenesis with and without Antley-Bixler syndrome. Nature Genetics . 2004;36(3):228–230. doi: 10.1038/ng1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huang N., Pandey A. V., Agrawal V., et al. Diversity and function of mutations in p450 oxidoreductase in patients with Antley-Bixler syndrome and disordered steroidogenesis. The American Journal of Human Genetics . 2005;76(5):729–749. doi: 10.1086/429417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Merla G., Howald C., Henrichsen C. N., et al. Submicroscopic deletion in patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome influences expression levels of the nonhemizygous flanking genes. The American Journal of Human Genetics . 2006;79(2):332–341. doi: 10.1086/506371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hart S. N., Zhong X. B. P450 oxidoreductase: genetic polymorphisms and implications for drug metabolism and toxicity. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism and Toxicology . 2008;4(4):439–452. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Agrawal V., Huang N., Miller W. L. Pharmacogenetics of P450 oxidoreductase: effect of sequence variants on activities of CYP1A2 and CYP2C19. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2008;18(7):569–576. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e32830054ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sandee D., Morrissey K., Agrawal V., et al. Effects of genetic variants of human P450 oxidoreductase on catalysis by CYP2D6 in vitro. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2010;20(11):677–686. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e32833f4f9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Subramanian M., Agrawal V., Sandee D., Tam H. K., Miller W. L., Tracy T. S. Effect of P450 oxidoreductase variants on the metabolism of model substrates mediated by CYP2C9.1, CYP2C9.2, and CYP2C9.3. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2012;22(8):590–597. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e3283544062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang J. J., Zhang H., Ding X. L., Ma S., Miao L. Y. Effect of the P450 oxidoreductase ∗28 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in Chinese healthy male volunteers. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2012;69(4):807–812. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.de Jonge H., Metalidis C., Naesens M., Lambrechts D., Kuypers D. R. The P450 oxidoreductase ∗28 SNP is associated with low initial tacrolimus exposure and increased dose requirements in CYP3A5-expressing renal recipients. Pharmacogenomics . 2011;12(9):1281–1291. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen X., Pan L. Q., Naranmandura H., Zeng S., Chen S. Q. Influence of various polymorphic variants of cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) on drug metabolic activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2B6. PLoS One . 2012;7(6):p. e38495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wortham M., Czerwinski M., He L., Parkinson A., Wan Y. J. Y. Expression of constitutive androstane receptor, hepatic nuclear factor 4α, and P450 oxidoreductase genes determines interindividual variability in basal expression and activity of a broad scope of xenobiotic metabolism genes in the human liver. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2007;35(9):1700–1710. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hart S. N., Wang S., Nakamoto K., Wesselman C., Li Y., Zhong X. B. Genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase influence microsomal P450-catalyzed drug metabolism. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2008;18(1):11–24. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e3282f2f121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eroglu C., Pala C., Kaynar L., et al. Comparison of total body irradiation plus cyclophosphamide with busulfan plus cyclophosphamide as conditioning regimens in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Leukemia and Lymphoma . 2013;54(11):2474–2479. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.779691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xie H., Griskevicius L., Stahle L., et al. Pharmacogenetics of cyclophosphamide in patients with hematological malignancies. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2006;27(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ekhart C., Doodeman V. D., Rodenhuis S., Smits P. H., Beijnen J. H., Huitema A. D. Influence of polymorphisms of drug metabolizing enzymes (CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, GSTA1, GSTP1, ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1) on the pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide and 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics . 2008;18(6):515–523. doi: 10.1097/fpc.0b013e3282fc9766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shu W., Chen L., Hu X., et al. Cytochrome P450 genetic variations can predict mRNA expression, cyclophosphamide 4-hydroxylation, and treatment outcomes in Chinese patients with non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2017;57(7):886–898. doi: 10.1002/jcph.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cocca M., Bedognetti D., La Bianca M., Gasparini P., Girotto G. Pharmacogenetics driving personalized medicine: analysis of genetic polymorphisms related to breast cancer medications in Italian isolated populations. Journal of Translational Medicine . 2016;14(1):p. 22. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0778-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ribaudo H. J., Haas D. W., Tierney C., et al. Pharmacogenetics of plasma efavirenz exposure after treatment discontinuation: an adult AIDS clinical trials group study. Clinical Infectious Diseases . 2006;42(3):401–407. doi: 10.1086/499364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xie H. J., Yasar U., Lundgren S., et al. Role of polymorphic human CYP2B6 in cyclophosphamide bioactivation. The Pharmacogenomics Journal . 2003;3(1):53–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ming Z., Yongqiang Z., Zijin Z., Yan X., Di C., Xiaoxin T. Severe and prolonged cyclophosphamide-induced hepatotoxicity in a breast cancer patient carrying a CYP2B6∗7 variant. Pharmacogenomics . 2019;20(16):1119–1124. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2019-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Udagawa C., Sasaki Y., Suemizu H., et al. Targeted sequencing reveals genetic variants associated with sensitivity of 79 human cancer xenografts to anticancer drugs. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine . 2018;15(2):1339–1359. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hesse L. M., He P., Krishnaswamy S., et al. Pharmacogenetic determinants of interindividual variability in bupropion hydroxylation by cytochrome P450 2B6 in human liver microsomes. Pharmacogenetics . 2004;14(4):225–238. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200404000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ariyoshi N., Ohara M., Kaneko M., et al. Q172H replacement overcomes effects on the metabolism of cyclophosphamide and efavirenz caused by CYP2B6 variant with Arg262. Drug Metabolism and Disposition . 2011;39(11):2045–2048. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Helsby N., Yong M., Burns K., Findlay M., Porter D. Cyclophosphamide bioactivation pharmacogenetics in breast cancer patients. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology . 2021;88(3):533–542. doi: 10.1007/s00280-021-04307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shu W., Guan S., Yang X., et al. Genetic markers in CYP2C19 and CYP2B6 for prediction of cyclophosphamide’s 4-hydroxylation, efficacy and side effects in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . 2016;81(2):327–340. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Labib R. M., A Abdelrahim M. E., Elnadi E., Hesham R. M., Yassin D. CYP2B6rs2279343 is associated with improved survival of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma treated with cyclophosphamide. PLoS One . 2016;11(7):p. e0158890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Barnett S., Errington J., Sludden J., et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of cyclophosphamide in a neonate and infant childhood cancer patient population. Pharmaceuticals . 2021;14(3):p. 272. doi: 10.3390/ph14030272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lang T., Klein K., Richter T., et al. Multiple novel nonsynonymous CYP2B6 gene polymorphisms in Caucasians: demonstration of phenotypic null alleles. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics . 2004;311(1):34–43. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yao S., Barlow W. E., Albain K. S., et al. Gene polymorphisms in cyclophosphamide metabolism pathway,treatment-related toxicity, and disease-free survival in SWOG 8897 clinical trial for breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research . 2010;16(24):6169–6176. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pinto N., Navarro S. L., Rimorin C., Wurscher M., Hawkins D. S., McCune J. S. Pharmacogenomic associations of cyclophosphamide pharmacokinetic candidate genes with event-free survival in intermediate-risk rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatric Blood and Cancer . 2021;68(11):p. e29203. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cartin-Ceba R., Indrakanti D., Specks U., et al. The pharmacogenomic association of fcγ receptors and cytochrome P450 enzymes with response to rituximab or cyclophosphamide treatment in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis. Arthritis and Rheumatology . 2017;69(1):169–175. doi: 10.1002/art.39822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jamieson D., Lee J., Cresti N., et al. Pharmacogenetics of adjuvant breast cancer treatment with cyclophosphamide, epirubicin and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology . 2014;74(4):667–674. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vukovic V., Karan-Djurasevic T., Antic D., et al. Association of SLC28A3 gene expression and CYP2B6∗6 allele with the response to fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Pathology and Oncology Research . 2020;26(2):743–752. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hwang M., Medley S., Shakeel F., et al. Lack of association of CYP2B6 pharmacogenetics with cyclophosphamide toxicity in patients with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer . 2022;30(9):7355–7363. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Veal G. J., Cole M., Chinnaswamy G., et al. Cyclophosphamide pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics in children with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. European Journal of Cancer . 2016;55:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hassan M., Andersson B. S. Role of pharmacogenetics in busulfan/cyclophosphamide conditioning therapy prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pharmacogenomics . 2013;14(1):75–87. doi: 10.2217/pgs.12.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tulsyan S., Agarwal G., Lal P., Mittal B. Significant role of CYP450 genetic variants in cyclophosphamide based breast cancer treatment outcomes: a multi-analytical strategy. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine . 2014;434:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schirmer J. H., Bremer J. P., Moosig F., et al. Cyclophosphamide treatment-induced leukopenia rates in ANCA-associated vasculitis are influenced by variant CYP450 2C9 genotypes. Pharmacogenomics . 2016;17(4):367–374. doi: 10.2217/pgs.15.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.El-Serafi I., Afsharian P., Moshfegh A., Hassan M., Terelius Y. Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase influences CYP2B6 activity in cyclophosphamide bioactivation. PLoS One . 2015;10(11):p. e0141979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ma J., Ramachandran S., Fiedorek F. T., Zeldin D. C. Mapping of the CYP2J cytochrome P450 genes to human chromosome 1 and mouse chromosome 4. Genomics . 1998;49(1):152–155. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]