Abstract

Sialic acid is a unique sugar moiety that resides in the distal and most accessible position of the glycans on mammalian cell surface and extracellular glycoproteins and glycolipids. The potential for sialic acid to obscure underlying structures has long been postulated, but the means by which such structural changes directly affect biological processes continues to be elucidated. Here, we appraise the growing body of literature detailing the importance of sialic acid for the generation, differentiation, function, and death of hematopoietic cells. We conclude that sialylation is a critical post-translational modification utilized in hematopoiesis to meet the dynamic needs of the organism by enforcing rapid changes in availability of lineage-specific cell types. Though long thought to be generated only cell-autonomously within the intracellular ER-Golgi secretory apparatus, emerging data also demonstrate previously unexpected diversity in the mechanisms of sialylation. Emphasis is afforded to the mechanism of extrinsic sialylation, whereby extracellular enzymes remodel cell surface and extracellular glycans, supported by charged sugar donor molecules from activated platelets.

Keywords: hematopoiesis, sialic acid, galactose, sialyltransferase, lectins, siglec, galectin, cell death, bone marrow, extrinsic sialylation

Graphical Abstract

Sialylation is a post-translational glycosylation modification utilized in hematopoiesis to meet the dynamic needs of the organism by enforcing rapid changes in availability of lineage-specific cell types. Though long thought to be generated only cell-autonomously within the intracellular ER-Golgi secretory apparatus, emerging data also demonstrate previously unexpected diversity in the mechanisms of sialylation. Emphasis is afforded to the mechanism of extrinsic sialylation, whereby extracellular enzymes remodel cell surface and extracellular glycans, supported by charged sugar donor molecules from activated platelets.

Introduction

Maintaining effective levels of functional blood cells of all lineages is essential throughout the lifetime of an organism. These lineages include not only red cells, platelets, granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages, but also adaptive immune cells such as T and B cells, to name a few. Although cell-intrinsic mechanisms execute the transitions required for normal development and turnover, these mechanisms need to be responsive to systemic cues conveying the immediate need for specific cell types. Glycans of cell surfaces and the extracellular milieu represent a critical layer of the cell-niche interface through which such cues are conveyed.

One glycan motif that profoundly impacts blood cell biology is sialic acid, a 9-carbon negatively charged monosaccharide occupying the outermost (and arguably the most exposed) positions of glycan chains in mammals and other deuterostomes. At least 3 important classes of mammalian lectins, or carbohydrate recognizing receptors, mediate the biological repercussions of the presence or absence of sialic acid: 1) Siglecs (sialic-acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins), which bind sialic acid and often contain intracellular cell signaling domains1–3, 2) Galectins, a large family of proteins recognizing the underlying β-galactoside moiety uncovered by the removal of sialic acid2,4, and 3) Selectins, which recognize sialylated tetra-saccharide structures such as sialyl Lewis X (SLex)5,6. The latter, which exists in three varieties (E, L, and P-selectin), constitutes a well-studied class of cell adhesion molecules that mediate tethering interactions under shear stress between leukocytes and endothelial cells. Twenty distinct sialyltansferases mediate the attachment of sialic acid in α2,3, α2,6, or α2,8 linkage to underlying glycans, and four mammalian sialidases catalyze their removal7,8. The emerging field of how sialylation contributes to production, maintenance, and function of blood cells is herein appraised.

Modes of Sialylation

Investigations into one particular sialyltransferase, ST6GAL1, which mediates the transfer of Sia(α2,6) to Gal(β1,4)GlcNAc-R termini of glycans, are notable for uncovering unexpected diversity in the modes of sialylation in biological systems. ST6GAL1 is associated with a diverse array of clinical conditions including stress, inflammation, atherosclerosis, alcoholism, as well as malignancies – particularly colon, breast and pediatric acute leukemias9–16. The case for its role in oncogenic pathways is particularly strong, especially for those signaling pathways affecting behaviors such as sustained proliferation, stemness, chemo-/radiation-resistance, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and invasion17–22. ST6GAL1 is also implicated in suppressing differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells18.

Sialyltransferases classically reside within the intracellular ER-Golgi secretory network, where they modify glycoconjugates in biosynthetic transit. Full-length ST6GAL1 has the hallmark of an archetypical glycosyltransferase: a type-2 transmembrane protein with a cytosolic N-terminal domain, a transmembrane domain, a stem region, and a globular C-terminal catalytic domain23,24. However, ST6GAL1 is also abundant in extracellular compartments25. The beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) was identified early as a critical enzyme that proteolytically liberates the C-terminal catalytic domain of ST6GAL1 from its transmembrane domain, generating a soluble yet catalytically active smaller form amenable to secretion26–29. Hepatocytes are the principal source of soluble ST6GAL1 in the circulation30, and their secretion of ST6GAL1 is a part of the acute phase response31,32. Hepatic expression of ST6GAL1 is under the control of glucocorticoids33 and cytokines that remain incompletely defined33,34. Many other cells and tissues also release ST6GAL1 into their environment, including lactating mammary glands35, neonatal intestinal epithelium36,37, and mature B cells38. Cancer cells, most notably lung, colon, and breast express and release copious quantities of ST6GAL139–43. Activated human platelets are also a rich source of circulating ST6GAL1, as well as a number of other extracellular glycosyltransferases that can be detected in plasma25.

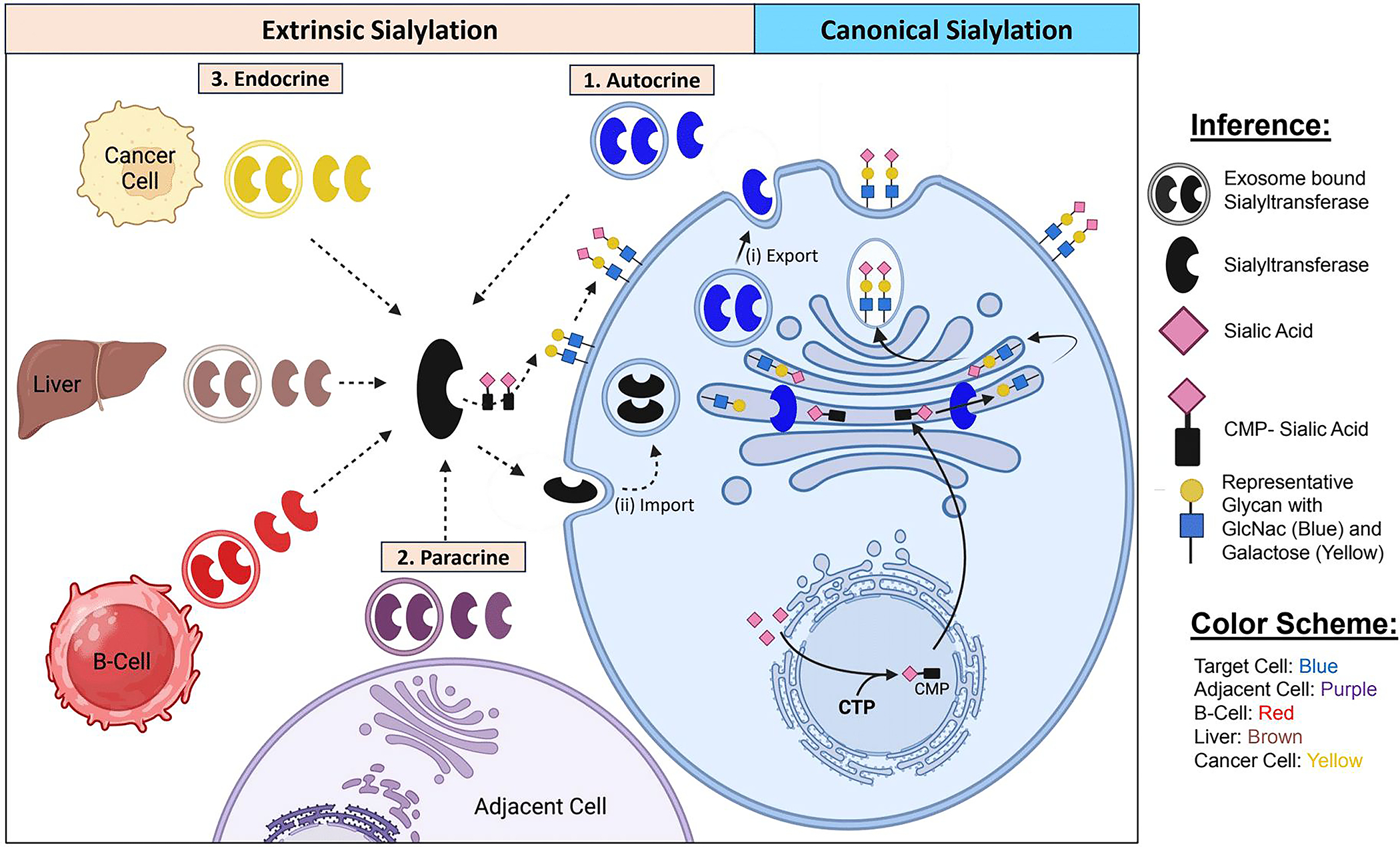

The hypothesis of ‘Extrinsic Sialylation’ posits that extracellular sialyltransferases, rather than simply being the byproducts of intracellular sialyltransferase expression, remain enzymatically active and directly sialylate secreted or cell-surface glycoproteins by a Golgi-independent pathway25. Originally proposed by our group as an explanation for the discrepancies between intracellular sialyltransferase expression and cell surface glycoprotein sialylation, extrinsic sialylation predicts that cellular sialylation can be controlled either cell-autonomously or non-cell-autonomously, depending on the origin of the sialyltransferase. We propose three subtypes of extrinsic sialylation – endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine – underscoring the biological relevance of the physical relationship between secreting and target cells. Further, this hypothesis allows for rapid local and systemic modification of sialic acid-dependent processes by alterations in abundance of secreted sialyltransferase in a given context. In line with the observations that blood sialyltransferase levels vary in states of stress or disease, extrinsic sialylation provides a paradigm by which these changes may produce biologically relevant outcomes. ‘Intrinsic Sialylation’, in contrast, describes the classically accepted sialylation mechanism, mediated by cell-autonomous sialyltransferases residing within the intracellular ER-Golgi network. This is schematically depicted in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Modes of sialylation.

Sialic acid is synthesized in the cytosol from glycolytic precursors, then conjugated to cytidine triphosphate (CTP) to form CMP-Sialic acid, the charged sugar donor substrate that participates in sialylation reactions. The secretory pathway involves progressive remodeling of glycans attached to glycoproteins or glycolipids as they transit through the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Intrinsic sialylation of a terminally galactosylated structure occurs in the trans-Golgi, after which glycoconjugates are typically transported to be embedded in the membrane or exported. Extrinsic sialylation differs in that extracellular sialyltransferases catalyze sialylation of secreted or cell surface glycans, independently of the ER-Golgi pathway. The relationship between the cell producing the sialyltransferase and the target cell can vary, as illustrated by autocrine (self-sialylation by secreted enzyme), paracrine (sialylation of a tissue by localized enzyme secretion), or endocrine (sialylation of distant targets after transport in the blood). Emerging evidence suggests that extracellular sialyltransferase can also be imported into recipient cells and utilized in intracellular reactions.

A conceptual stumbling block to the plausibility of extrinsic sialylation has been the contention that the necessary sugar donor substrate, CMP-Sia, is absent in the extracellular milieu. This notion was challenged initially by Wandall et al44, who demonstrated that platelets store such sugar donor molecules within granules and release them upon activation. Later, the ability of activating platelets to supply sialic acid to extracellular sialyltransferases was demonstrated unequivocally in vitro and in vivo45,46 and led to the notion that platelet degranulation is a central event regulating extrinsic sialylation25. Extracellular vesicles, released from both living and dying cells, are also hypothesized to contribute to the extracellular supply of CMP-Sia.

Extrinsic sialylation may also operate by direct exchange of sialyltransferases between cells. We have observed that the larger, full-length ST6GAL1 isoform, which presumably has not been subject to BACE1 cleavage, also exists extracellularly as part of the secretome of breast cancer and multiple myeloma cells47,48. This secreted larger ST6GAL1, owing to retention of the transmembrane domain, may be embedded in membrane-containing extracellular vesicles48,49. There is emerging evidence that ST6GAL1 is found in small, non-membranous extracellular nanoparticles called exomeres, which can be internalized by recipient cells to remodel cell-surface glycans49. Extracellular vesicle mediated internalization of another exo-glycosyltransferase, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-V (GnT-V), was also reported recently50. Whether extracellular sialyltransferases universally exist within nanoparticles and the extent to which intercellular sialyltransferase exchange mediates sialylation remain unknown.

Hematopoiesis in the Bone Marrow

In adults, the marrow is the principal site for the production of blood cells of all lineages from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC). Blood cell production in secondary sites, or extramedullary hematopoiesis, also occurs, especially in response to extreme stress caused by diseases such as severe infections or blood cancers, or during fetal development. Two principal niches have been proposed as functionally distinct microenvironments within the bone marrow – the endosteal niche which lies adjacent to trabecular bone and houses quiescent HSPC, and the sinusoidal niche, which is associated with active HSPC, along with various cell types ingressing and egressing from the marrow51. The function of sialic acid in the earliest hematopoietic progenitors remains poorly understood. However, homing of HSPC into the marrow is dependent on tethering interactions between α2,3-sialic acid containing tetrasaccharide structures and E-selectin, which is constitutively expressed on marrow endothelial cells 52,53. This is in contrast to endothelium of other tissues, in which E-selectin only becomes present on the cell surface hours after transcriptional upregulation by pro-inflammatory IL-1, TNF-α, or LPS54. On human HSPC, a specialized Slex-containing CD44 glycoform called hematopoietic cell E/L-selectin ligand (HCELL) is a high affinity E-selectin ligand that is necessary for marrow homing55,56. When this ligand is artificially synthesized by FTVI exofucosylation of CD44 on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), they gain the ability to migrate into the bone marrow despite lacking the chemokine receptor CXCR457. In regards to α2,6-sialylation, it is noteworthy that lineage-negative hematopoietic progenitors in the mouse marrow are virtually absent of native ST6GAL1 expression. Yet, these hematopoietic progenitors are richly endowed with cell surface α2,6-sialic acids due to the action of hepatocyte-derived ST6GAL1, as demonstrated in conditional knockout and bone marrow transplantation experiments58. As HSPCs differentiate into the early, lineage-committed cells of the bone marrow, the functional importance of sialic acid becomes increasingly clear, as detailed below.

In the platelet lineage, productive thrombopoiesis requires the timely expression of both galactosylated and sialylated glycans. Medullary TPO and CXCL12 stimulate expression of B4GALT1 galactosyltransferase, which galactosylates β1 integrin to inhibit ligand binding and signaling 59. This inhibition is needed to form the demarcation system (DMS), by which a single megakaryocyte is partitioned into thousands of proplatelets59. Expression of ST3GAL1 and ST3GAL2 are also necessary for proplatelet formation60. Sialylation of megakaryocytes by ST3GAL1 sialyltransferase, interestingly, obscures the Thomsen-Friedenreich (TF) autoantigen, preventing their recognition and untimely destruction by type I interferon-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells61.

Early red blood cell precursors are nucleated in marrow erythroblastic islands, each consisting a single Siglec-1+ (CD169) macrophage that provisions iron to nearby erythroblasts62. This macrophage-erythroblast interaction is mediated by VCAM-1 - which binds erythroblast integrins - and Siglec-1, which binds a sialylated erythroblast ligand, likely MUC1 or CD4363–65. Depletion of medullary Siglec-1+ macrophages compromises the dynamic reserve to support erythropoiesis under stressful conditions, such as anemia and thalassemia62.

In the monocyte lineage, sialic acid supports early maturation but resists later differentiation into macrophages (Fig 2a). Extracellular ST6GAL1 is rapidly sequestered on the surface of monocytes to extrinsically sialylate the M-CSF receptor, activating NF-kB, ERK, and AKT signaling and upregulating the key myeloid transcription factor PU.166. Further sialylation by ST6GAL1, ST3GAL1, and ST3GAL4 accompanies differentiation into dendritic cells67. When monocytes prepare for extravasation, two parallel mechanisms – upregulation of surface neuraminidases and cleavage and release of sialyltransferases by BACE-1 – enable the membrane desialylation needed to trigger β1 integrin clustering and binding to VCAM-1, allowing for tissue infiltration and macrophage differentiation27,68.

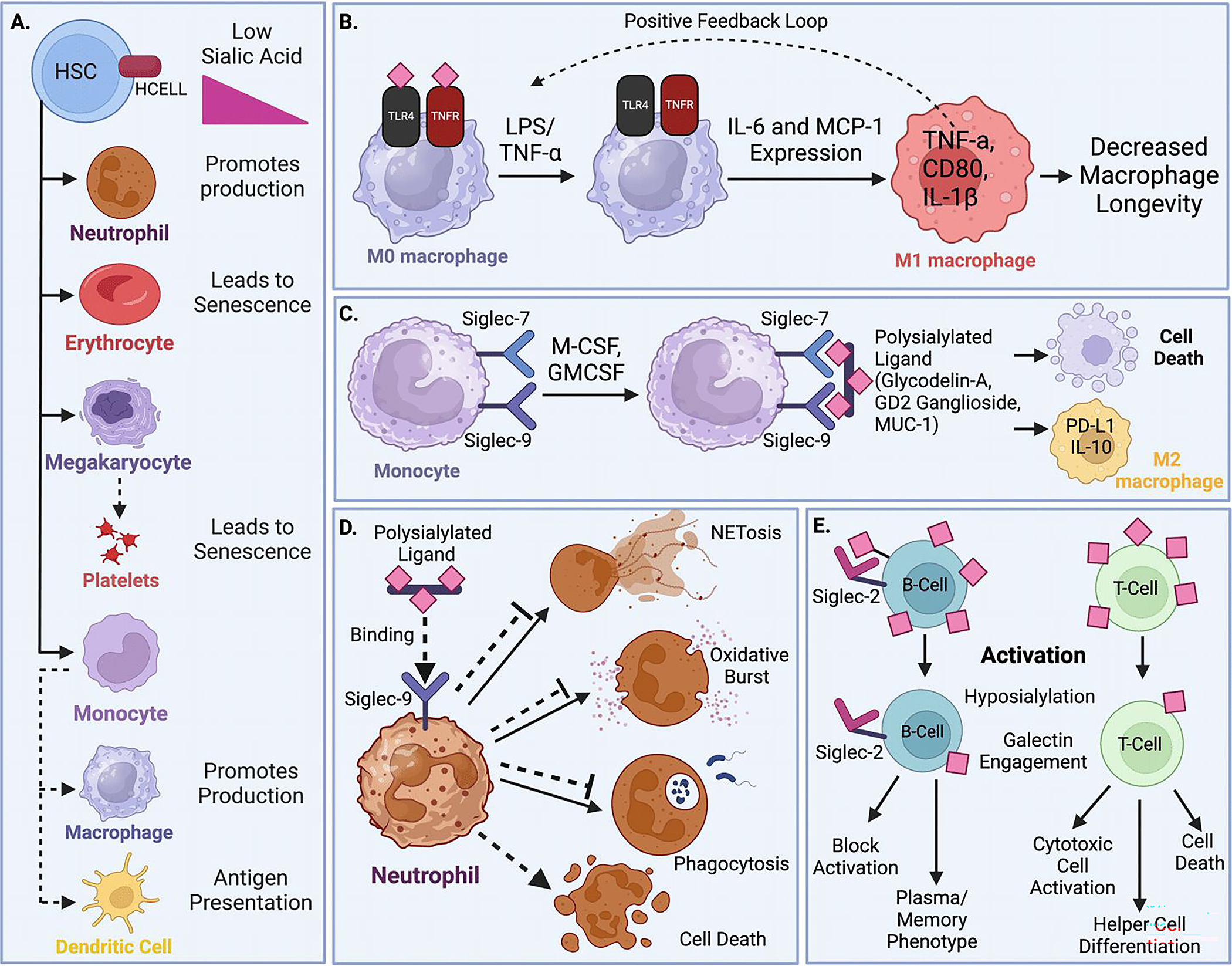

Fig 2. Diverse functions of sialic acid in hematopoietic cells.

(A) Hematopoietic cells accrue sialic acid during early development, but rapidly shed their sialic acid when activated or in response to inflammatory stimuli. This desialylation rapidly generates pro-inflammatory granulocytes and macrophages, prepares dendritic cells for antigen presentation, and accelerates the senescence and turnover of platelets and erythrocytes. (B) Exposure to LPS and TNF-α in macrophages prompts rapid desialylation of the crucial cell surface receptors TLR4 and TNFR, activating a positive feedback loop of inflammation that promotes M1 differentiation but ultimately limits macrophage lifespan. (C) Macrophages and granulocytes express cell surface Siglecs to sense environmental sialic acid. Growth factors M-CSF and GM-CSF stimulate monocyte Siglec-7 and Siglec-9 expression, which sense tissue sialic acid ligands to promote PD-L1 and IL-10 expression, M2 differentiation, and cell death. (D) On neutrophils, Siglec-9 engages erythrocyte sialic acids to inhibit ROS production, NETosis, antimicrobial functions, and promote inflammatory cell death. (E) Lymphocytes possess abundant sialic acid, which in B cells plays a critical role in meeting developmental milestones via engagement of Siglec-2/CD22. Mature B and T cells rapidly lose sialic acid upon activation, exposing underlying galactose for galectin activation. In B cells, desialylation limits BCR signaling and allows for galectin engagement, which directs differentiation into memory or plasma cell phenotypes. In T cells, desialylation allows for robust cytotoxic cell activation but also promotes cell death. Galectin engagement further influences differentiation into specific helper T cell subtypes.

In the granulocytic lineage, secreted ST6GAL1 sialylates the earliest FcγRII/III+ granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP) and granulocyte progenitor (GP) populations, blocking G-CSF/STAT3 signaling and expression of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and C/EBP-alpha (Fig 2a)69. Mice lacking hepatic-derived circulatory ST6GAL1 are predisposed to neutrophilia, whereas treatment with exogenous ST6GAL1 tempers systemic neutrophilic inflammation58,70–72. ST6GAL1 similarly blocks the bone marrow development of eosinophils, reducing airway eosinophilia by an IL-5 dependent pathway73.

Among lymphocytes, the bone marrow is the site of B cell maturation, wherein galactose and sialic acid expression heralds specific stages of development. Assembly of the ‘pre-BCR’ sustains temporary signaling to support development of pre-B cells. Galactosylation of surface ligands enables direct contact with galectin-1 expressing stromal cells, trapping the pre-BCR in a galectin-1 lattice that also immobilizes galactosylated α4β1, α4β7, and α5β1 integrins on B cells. Formation of this synapse potently stimulates the pre-BCR’s intracellular tyrosine kinase activity74,75. At the immature stage, a complete BCR is assembled, accompanied by increased sialylation of CD22 and CD45 by ST6GAL1, triggering robust BCR activation, the primary cue that positively selects cells at this stage for further maturation. Although most B cell sialylation is driven by endogenous ST6GAL1, immature B cells are also susceptible to extrinsic sialylation by bloodborne ST6GAL1. Extrinsic sialylation by hepatic ST6GAL1 licenses B cells for differentiation and survival, enhancing BCR and BAFF-mediated NF-kB, PI3K, and MAPK signaling76. Even after differentiation into mature stages in the periphery, extrinsically sialylated cells continue to exhibit improved BCR signals, proliferation, and IgG production by a CD22-dependent mechanism77.

Erythrocytes and Platelets

In the periphery, the function of sialic acid is most straightforward in the erythrocyte and platelet lineages. In both, sialic acid is a marker of youth and its loss signals senescence and cell death (Fig 2a). Such a response to desialylation may have developed as an adaptation to sepsis. Both platelets and erythrocytes lose sialic acid moieties during sepsis, attributed to the presence of microbial sialidases in the bloodstream. Erythrocyte Lu/BCAM, normally tethered in cis to sialylated glycophorin-C on the cell surface, is liberated upon desialylation to find new ligands such as laminins of the vasculature, an interaction associated with erythrocyte stasis and vessel occlusion in stroke and myocardial infarction78–80. Conversely, mice lacking the receptor to recycle desialylated platelets, when infected with Streptococcus pneumoniae, develop disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a deadly condition characterized by widespread thrombosis81. The ‘permissive thrombocytopenia’ triggered by platelet desialylation is thought to prevent this process by reducing the availability of platelets for maladaptive clots.

Mature erythrocyte surfaces are coated in heavily glycosylated glycophorins, the sialylation of which is necessary for entry by Plasmodium organisms, the causative agents of malaria82–86. The evolutionary pressure to preserve a nonsense mutation in the cytidine monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) gene in great apes 3.2 million years ago, is thought to have interfered with Plasmodium infection by depleting the glycolyl subtype of sialic acid on erythrocytes87,88. Several mechanisms also couple glycophorin sialylation to cellular half-life. First, loss of sialic acid alters membrane electrostatic charge to disrupt erythrocyte morphology, creating a more spheroid, less deformable shape that is recognized by phagocytes of the reticuloendothelial system89. Second, exposure of underlying galactose also promotes recognition by macrophage galectin receptors, prompting phagocytosis and destruction90. Third, sialidases directly induce erythrocyte cell death, or erypoptosis, by increasing phosphatidylserine presentation and release of intracellular calcium stores, an effect that can be recapitulated by exogenous sialidases and prevented by exogenous sialyltransferases89,91–93.

Glycans play a profound role in platelet half-life, as uncovered by studies of platelet storage. Chilled platelets are rendered obsolete upon transfusion owing to two mechanisms. First, briefly chilled platelets aggregate Gp1ba, facilitating their recognition and uptake by hepatic macrophages via complement receptor 3 (CR3/aMB2 integrin)94,95. This interaction depends on the exposure of terminal N-acetylglucosamine of Gp1ba and can be reversed by the exogenous provision of galactose or UDP-Gal96,97. In contrast, platelets that have undergone long-term refrigeration can no longer be rescued by galactosylation, as they release endogenous sialidases to completely desialylate Gp1ba, naturally exposing underlying galactose that is vulnerable to cleavage and inactivation by the matrix metalloproteinase ADAM1798. Desialylated Gp1ba also tends to cluster and is recognized by the galectin Ashwell-Morell receptor expressed on macrophages and hepatocytes, leading to platelet destruction and thrombocytopenia, as observed in ST3GAL4-deficient mice99. Notably, platelet phagocytosis in hepatocytes activates JAK2-STAT3 signaling, leading to the release of TPO to stimulate restorative bone marrow thrombopoiesis100.

Monocytes, Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, and Granulocytes

Professional phagocytes of the myeloid lineage, including monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as granulocytic neutrophils and eosinophils, are poised for activation in response to infectious and inflammatory triggers. A general trend in phagocytes is an inflammatory activity that inversely correlates to their degree of sialylation. Macrophages are generally poorly sialylated in comparison to monocytes and dendritic cells, and further lose sialic acid in response to two pro-inflammatory molecules - LPS and TNF-α (Fig 2b)101. LPS triggers trafficking of NEU1 to the cell membrane in complex with cathepsin A, where it desialylates the LPS receptor, TLR4102. Desialylated TLR4 dissociates from Siglec-E, increasing its cell surface half-life, signaling potential, and downstream expression of IL-6 and MCP-1102,103. Ultimately, this promotes an M1 phenotype, with expression of CD80, TNF-α, and IL-1β, creating a positive feedback pro-inflammatory pathway in response to gram-negative infection104.

In contrast, TNF-α upregulates BACE-1, liberating ST6GAL1 and reducing sialylation of β1 integrin, thereby promoting adhesion of macrophages to endothelial cells105. ST6GAL1 release also depletes sialylation of the TNF receptor, which selectively inhibits the pro-survival effects of TNF-α 106,107. Although short-term TNFα-induced NF-kB activation remains intact in ST6GAL1-deficient macrophages, sustained NF-kB activation, central to the cytokine’s pro-survival effect, is compromised, resulting in tissue-infiltrating but short-lived macrophages107.

In dendritic cells, desialylation improves phagocytosis, production of IFN-g, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-6, and antigen presentation to T cells108. The effects of sialic acid on antigen presentation are likely secondary to the major histocompatibility complex. Desialylated MHC-I associates more efficiently with β2-microglobulin, binds peptides with higher affinity, and has a longer half-life109. Loss of sialic acid, by either sialidase treatment or knockout of ST6GAL1 or ST3GAL1, also increases MHC-II expression and antigen presentation to favor a Th1 response110. Pro-inflammatory stimuli, such as LPS, induce desialylation via NEU1 and NEU3, whereas glucocorticoids stimulate an increase in sialylation and differentiation into a more tolerogenic phenotype111,112.

Recent literature supports the idea that neutrophils share some of the pathways first described in macrophages and dendritic cells. For instance, activated neutrophils, including both those exposed to LPS and those isolated from individuals with COVID-19, exhibit high NEU1 activity, which improves TLR4 signaling, leading to exuberant ROS production and detrimental neutrophilic inflammation by a MMP-9 dependent pathway113,114. NEU1 also improves neutrophil extravasation by desialylation of β2 integrin (CD11b/CD18), allowing for higher affinity interactions with endothelial ICAM-1/ICAM-2, especially in the lung115–117.

A second trend in phagocytes is that they are potently suppressed by environmental sialic acid via Siglec engagement (Fig 2c). Siglec-7 and Siglec-9 are expressed in monocytes exposed to M-CSF and GM-CSF, and bind ST8SIA6-produced polysialic acid on ligands such as glycodelin-A, GD2 ganglioside, and MUC-1118–122. Ligand engagement facilitates differentiation into an immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, with high PD-L1 and IL-10 expression in the context of the tumor microenvironment 121,123,124. The ectodomain of Siglec-9 can also act in a paracrine fashion when proteolytically shed, likely binding to sialoglycans on CCR2 to alter MCP-1/CCR2 signaling, promoting the polarization of macrophages into an M2 phenotype 125,126,127. Both Siglec-9 and its murine counterpart Siglec-E trigger macrophage apoptosis when engaged with aortic endothelial ligands, creating a negative feedback pathway to limit vascular inflammation128,129. Siglec-7 can also trigger ROS-dependent, non-apoptotic cell death in macrophages, independent of intracellular phosphatase recruitment130.

Neutrophils express Siglec-9, which binds α2,3-sialyl ligands on abundant mucosal glycoproteins and executes cell-fate decisions for the activated neutrophil via its intracellular ITIM domain (Fig 2d)131–133. When engaged with environmental sialic acid, Siglec-9 limits tissue inflammation by blocking oxidative burst, neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, and pathogen clearance134,135. An important source of this environmental “self” signal is erythrocytes, which engage neutrophil Siglec-9 via glycophorin A to limit neutrophil activation in blood 136. When activated neutrophils ligate Siglec-9, however, their endogenous upregulation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production triggers ROS-dependent cell death, rapidly suppressing inflammation137. Interestingly, pro-inflammatory neutrophils have been observed to shed Siglec-9, shielding exposed sialic acid to avoid this inhibition of antimicrobial activity towards bacteria138,139.

Finally, Siglec-8 (or murine Siglec-H) binds ST3GAL3-generated α2,3-sialyl ligands of the airway epithelium to suppress eosinophil and mast cell activation and survival140–142. In eosinophils activated by IL-5 and IL-33, Siglec-8 ligation enables a unique β2 integrin-mediated cell death pathway, which signals via Akt, p38, and c-Jun to activate NADPH oxidase, generating excessive ROS, mitochondrial damage, and caspase activation143–149.

B and T Lymphocytes

In contrast to phagocytes, lymphocytes are generally heavily sialylated and depend on sialic acid to meet milestones in their development. When activated, however, they rapidly shed sialic acid and become susceptible to the effects of galectins, receptors that specifically recognize the freshly exposed underlying galactose moieties, which direct their further differentiation (Fig 2e).

In B cells, sialic acid biology is shaped by the siglec CD22, which binds the α2,6-sialic acid motif constructed by ST6GAL1. Owing to the inability to form CD22 ligands, ST6GAL1-deficient mice suffer diminished BCR signaling, proliferation, and antibody responses to T-dependent and T-independent antigens150–153. CD22 functions are context dependent. While its intracellular ITIM domain suppresses BCR signaling by SHP-1 phosphatase recruitment, its extracellular, sialic acid binding domain determines its proximity to the BCR in the plasma membrane154. Therefore, though the effects of ST6GAL1 deficiency are due to CD22 disengagement, complete CD22 deficiency paradoxically improves BCR signaling155–158. Major CD22 binding partners include CD45, IgM, and CD22 itself, the latter constituting homomultimeric microdomains that are regularly endocytosed and recycled via the endosomal pathway159–161. Both CD22-CD22 and CD22-CD45 complexes sequester phosphatase activity away from the BCR, improving BCR signaling strength. Transient interactions with CD45 sustain CD22’s characteristic Brownian motion, which also enables ‘surveillance’ of BCR signaling by both phosphatase recruitment and endocytosis162,163.

Given the importance of CD22 for BCR signaling, ST6GAL1 plays an outsized role in B cell development. Both CD22 expression and cell surface sialylation reach high levels in the late transitional B cell stages, with sialylation being sustained at high levels in the subsequent follicular but not marginal zone lineages76. Early transitional B cells, in contrast to mature follicular B cells, have yet to assemble a functional Lyn-CD22-SHP-1 pathway to inhibit BCR signaling and promote tolerance and are implicated in autoimmunity164. The poorly sialylated marginal zone B cells, a splenic population of IgM-producing, innate B cells, are abundant in ligand-free, or ‘unmasked’ CD22165. Interestingly, this population is entirely compromised by the loss of intrinsic ST6GAL1 expression, possibly reflecting a state of high BCR suppression from the overwhelming engagement of CD22 ligands in trans166,167. In contrast, other B cell populations compensate for ST6GAL1 and CD22 disruption by reliance on redundant pro-survival pathways, including those mediated by OCA-B or BLNK168,169.

It is worth noting that the major secreted product of B cells, immunoglobulins, are also glycosylated, with approximately 10% of IgG molecules bearing biantennary terminal sialic acid on their N-terminal Fc domain. The importance of IgG Fc sialylation by ST6GAL1, which is critical to the anti-inflammatory effects of IVIG therapy, has been recognized for some time. More recently, it has come to light that IgG sialylation can occur independently of B cells170–173. Studies suggest that IgG sialylation occurs after its secretion, but is also independent of hepatocytes and platelets, the major sources of blood ST6GAL1174–176. Other post-secretion modifications of IgG also occur, such as the deacetylation of sialic acid in pregnant mice, which occurs independently of B cells and confers transplacental protection to newborns against Listeria monocytogenes177. There is also evidence that sialylation of IgE and IgA similarly impact biologically relevant processes, which may occur by B cell-independent pathways178,179. However, considerable discrepancy persists, with IgG being sialylated by traditional intracellular pathways in a number of other models, highlighting the complexity and context dependence of immunoglobulin sialylation.

In T cells, the majority of sialylation is associated with ST3GAL1 expression, which gradually increases during T cell maturation. Regulatory T cells upregulate ST6GAL1 and increase their α2,6-sialylation, though the significance of this remains unclear180. In CD8+ T cells, ST3GAL1 reduces the strength of the MHCI-CD8b interaction by direct sialylation of CD8b, dampening sensitivity of T cells to low-affinity ligands181. CD8b sialylation also interferes with non-cognate (TCR-independent) interactions involved in intercellular adhesion182,183. Accordingly, exogenous desialylation of a CD103+ subset of CD8+ T cells sensitizes them to tumor antigens on glioma cells184. However, some researchers have cast doubt on this mechanism, as ST3GAL1-deficient cells have demonstrated preserved CD8-MHCI interactions in some models185.

When activated, both mature B and T cells undergo a dramatic loss of sialic acid, a change that has opposing outcomes in these two cell types186,187. In B cells, a loss of the highest affinity, sulfated CD22 ligands enables interactions with lower affinity ligands, including in trans with sialylated antigens presented by follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), which juxtapose CD22 with the BCR to block activation188. Nevertheless, a modest restraint of BCR signaling by CD22 is necessary to prevent excess calcium influx and cell death, as CD22-deficient germinal center B cells fail to fully form into plasma and memory B cells189–191. For T cells, reduced ST3GAL1 and increased NEU1 and NEU3 activity depletes sialic acid and replaces core 1 O-glycans with core 2 O-glycans187,192,193. Desialylation improves T cell signaling and proliferation, priming them for the immune response194. Desialylation of CD43, however, is a safeguard that triggers CD8+ T cell apoptosis if co-stimulation (of CD3 or by IL-2) does not occur195,196. Desialylation by NEU1 is also critical for IL-4, IgG1 and IgE synthesis owing to desialylation of the ganglioside GM3, which typically attenuates CD3-induced calcium signaling197,198. NEU1 enforces Th2 polarization by CD44 desialylation, enabling hyaluronic acid binding and asthmatic airway inflammation199,200.

Galectins, the receptors recognizing the underlying galactose moieties exposed by the removal of sialic acids, have a critical role in directing further differentiation of activated lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid tissues. Galectin-9 has a regulatory effect by inhibiting GC B cells and promoting regulatory T cells. In activated B cells, it interferes with CD22 interactions, incorporating CD22 and CD45 into BCR signalosomes to suppress signaling201,202. As a side note, GC B cells that construct I-branches on their N-glycans by expression of the glycosyltransferase GCNT2 can prevent galectin-9 binding, thus preserving their signaling203. In T cells, galectin-9, expressed under regulatory control of SMAD3, directly binds CD44 to assemble a CD44-TGF-β-TGF-βRI complex that stabilizes SMAD3 and FoxP3 activity, promoting the regulatory T cell phenotype204.

Galectin-3 promotes memory B cell production while suppressing T cell maturation. Expressed in naive B cells, it coordinates with IL-4 to promote survival and differentiation into memory B cells205. In T cells, galectin-3 binds CD45 and CD71 to induce cell death, particularly at the thymic double-negative stage206. Galectin-3 deficiency leads to exuberant IFN-g production and autoimmunity207.

Galectin-1 and galectin-8 are both expressed downstream of Blimp-1 in B cells and promote plasma cell differentiation205,208,209. Galectin-1 in particular activates Syk, Btk, and PI3K independently of the BCR and can also be secreted in a paracrine manner by nearby monocytes210,211. In T cells, galectin-1 binds glycans on CD7, CD43, and CD45 to promote phosphatase activity and death, an effect that can be inhibited by ST6GAL1-mediated sialylation, which obscures the galactose to block galectin binding212. Th1 and Th17 cells are most susceptible to galectin-1 mediated cell death, whereas Th2 cells are partially protected by their increased sialylation213. The structurally related galectin-2 binds β1 integrin and activates intrinsic apoptosis in T cells, with cytochrome C release, caspase 9 and 3 activation, and DNA fragmentation214. Galectin-8, on the other hand, is unique in binding α2,3-sialyl ligands synthesized by ST3GAL6 on FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, where it competes with macrophage siglec-1 to prevent cell death215,216. In so doing, galectin-8 sustains regulatory T cell TGF-β and IL-2 signaling and expression of CTLA-4 and IL-10217,218. Thus, the presence and balance of specific galectins drastically alters the differentiation of B and T cells to impact the overall immune response.

Conclusion

Sialylation has evolved as a means to rapidly and reversibly alter protein functions to effect broad cellular changes and dynamically meet the rapidly changing needs of an organism. The extensive body of work covered in this article illustrates a vast diversity of molecular pathways affected by sialylation in hematopoietic cells, regulating their generation, differentiation, function, and destruction. In the bone marrow, most developing cells gradually acquire sialic acid as both a mark of maturity and as a critical functional element that sustains survival and differentiation. In the periphery, desialylation is both a marker and a trigger of inflammation - activated cells of most lineages rapidly shed sialic acid, yet are resisted by non-hematopoietic sialoglycans, which maintain homeostasis by binding inhibitory siglecs. Finally, loss of sialic acid limits changes to cell fate, triggering death by a variety of mechanisms in myeloid and lymphoid lineages, or otherwise altering differentiation by galectin engagement. Recent findings have expanded the scope of how sialylation can occur to encompass non-traditional mechanisms such as extrinsic sialylation, wherein extracellular sialyltransferases catalyze sialylation outside the ER-Golgi complex. The current literature presents compelling data on how extrinsic sialylation by extracellular ST6GAL1 can convey critical endocrine, paracrine, and even autocrine signals by post-translational remodeling of glycans. Given that the current understanding of extrinsic sialylation is limited to a single sialyltransferase, it remains to be determined whether other glycosyltransferases can participate in similar extracellular reactions. Other glycosyltransferases including galactosyl-, fucosyl-, N-acetylglucosaminyl-, and other sialyl-transferases are also abundantly present in the extracellular milieu, in addition to the sialidases, galactosidases, and likely other glycosidases. Together, these extracellular anabolic and catabolic glycan modifying enzymes raise the tantalizing suggestion that wholesale glycan remodeling may occur by the extrinsic pathway. This knowledge continues to seek fruition in its application as novel therapeutic approaches for the endless spectrum of diseases involving the immune system and blood.

Funding statement:

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute P01HL151333 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases R01AI140736.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: There is no conflict of interest and nothing to declare by all authors.

Bibliography

- 1.Stanczak MA & Laubli H Siglec receptors as new immune checkpoints in cancer. Mol Aspects Med 90, 101112 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Gil A & Schnaar RL Siglec Ligands. Cells 10(2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macauley MS, Crocker PR & Paulson JC Siglec-mediated regulation of immune cell function in disease. Nat Rev Immunol 14, 653–666 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johannes L, Jacob R & Leffler H Galectins at a glance. J Cell Sci 131(2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varki A Selectin ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91, 7390–7397 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevilacqua MP & Nelson RM Selectins. J Clin Invest 91, 379–387 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glanz VY, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV & Orekhov AN Sialidase activity in human pathologies. Eur J Pharmacol 842, 345–350 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harduin-Lepers A, et al. The human sialyltransferase family. Biochimie 83, 727–737 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dabelic S, Flogel M, Maravic G & Lauc G Stress causes tissue-specific changes in the sialyltransferase activity. Z Naturforsch C 59, 276–280 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sage AP & Mallat Z Sialyltransferase activity and atherosclerosis. Circ Res 114, 935–937 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gracheva EV, et al. Sialyltransferase activity of human plasma and aortic intima is enhanced in atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1586, 123–128 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stibler H & Borg S Glycoprotein glycosyltransferase activities in serum in alcohol-abusing patients and healthy controls. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 51, 43–51 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong M, et al. Down-regulation of liver Galbeta1, 4GlcNAc alpha2, 6-sialyltransferase gene by ethanol significantly correlates with alcoholic steatosis in humans. Metabolism 57, 1663–1668 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J, et al. beta-Galactoside alpha2,6-sialyltranferase 1 promotes transforming growth factor-beta-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem 289, 34627–34641 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu J & Gu J Significance of beta-Galactoside alpha2,6 Sialyltranferase 1 in Cancers. Molecules 20, 7509–7527 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JJ & Lee M Increasing the alpha 2, 6 sialylation of glycoproteins may contribute to metastatic spread and therapeutic resistance in colorectal cancer. Gut Liver 7, 629–641 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gc S, Bellis SL & Hjelmeland AB ST6Gal1: Oncogenic signaling pathways and targets. Front Mol Biosci 9, 962908 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang YC, et al. Glycosyltransferase ST6GAL1 contributes to the regulation of pluripotency in human pluripotent stem cells. Sci Rep 5, 13317 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee M, Lee HJ, Bae S & Lee YS Protein sialylation by sialyltransferase involves radiation resistance. Mol Cancer Res 6, 1316–1325 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schultz MJ, et al. ST6Gal-I sialyltransferase confers cisplatin resistance in ovarian tumor cells. J Ovarian Res 6, 25 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz MJ, et al. The Tumor-Associated Glycosyltransferase ST6Gal-I Regulates Stem Cell Transcription Factors and Confers a Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype. Cancer Res 76, 3978–3988 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakraborty A, et al. ST6Gal-I sialyltransferase promotes chemoresistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by abrogating gemcitabine-mediated DNA damage. J Biol Chem 293, 984–994 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colley KJ, Lee EU, Adler B, Browne JK & Paulson JC Conversion of a Golgi apparatus sialyltransferase to a secretory protein by replacement of the NH2-terminal signal anchor with a signal peptide. Journal of Biological Chemistry 264, 17619 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colley KJ, Lee EU & Paulson JC The signal anchor and stem regions of the ·-galactoside ‡2,6-sialyltransferase may each act to localize the enzyme to the golgi apparatus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 267, 7784 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee-Sundlov MM, et al. Circulating blood and platelets supply glycosyltransferases that enable extrinsic extracellular glycosylation. Glycobiology 27, 188–198 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitazume S, et al. Molecular insights into {beta}-galactoside {alpha}2,6-sialyltransferase secretion in vivo. Glycobiology (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodard-Grice AV, McBrayer AC, Wakefield JK, Zhuo Y & Bellis SL Proteolytic shedding of ST6Gal-I by BACE1 regulates the glycosylation and function of alpha4beta1 integrins. J Biol Chem 283, 26364–26373 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugimoto I, et al. Beta-galactoside alpha2,6-sialyltransferase I cleavage by BACE1 enhances the sialylation of soluble glycoproteins. A novel regulatory mechanism for alpha2,6-sialylation. J Biol Chem 282, 34896–34903 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitazume S, et al. In vivo cleavage of alpha2,6-sialyltransferase by Alzheimer beta-secretase. J Biol Chem 280, 8589–8595 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Appenheimer MM, et al. Biologic contribution of P1 promoter-mediated expression of ST6Gal I sialyltransferase. Glycobiology 13, 591–600 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamieson JC, McCaffrey G & Harder PG Sialyltransferase: a novel acute-phase reactant Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology - B: Comparative Biochemistry 105, 29 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan HA, Woloski BMRNJ, Hellman M & Jamieson JC Studies on the effect of inflammation on rat liver and serum sialyltransferase: Evidence that inflammation causes release of Gal beta1–4 GlcNAc alpha2–6 sialyltransferase from liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry 258, 11505 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woloski BM, Fuller GM, Jamieson JC & Gospodarek E Studies on the effect of the hepatocyte-stimulating factor on galactose-beta 1----4-N-acetylglucosamine alpha 2----6-sialyltransferase in cultured hepatocytes. Biochemica et Biophysica Acta 885, 185 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jamieson JC, Lammers G, Janzen R & Woloski BMRNJ The acute phase response to inflammation: The role of monokines in changes in liver glycoproteins and enzymes of glycoprotein metabolism. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 87b, 11–15 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalziel M, et al. Mouse ST6Gal sialyltransferase gene expression during mammary gland lactation. Glycobiology 11, 407–412 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vertino-Bell A, Ren J, Black JD & Lau JT Developmental regulation of beta-galactoside alpha 2,6-sialyltransferase in small intestine epithelium. Dev Biol 165, 126–136 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irons EE, Cortes Gomez E, Andersen VL & Lau JTY Bacterial colonization and TH17 immunity are shaped by intestinal sialylation in neonatal mice. Glycobiology 32, 414–428 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wuensch SA, Huang RY, Ewing J, Liang X & Lau JT Murine B cell differentiation is accompanied by programmed expression of multiple novel beta-galactoside alpha2, 6-sialyltransferase mRNA forms. Glycobiology 10, 67–75 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De AK & Hardy RE Elucidation of sialyltransferase as a tumour marker. Indian Journal of Biochemistry & Biophysics 27, 452 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dwivedi C, Dixit M & Hardy RE Plasma sialyltransferase as a tumor marker. Cancer Detection & Prevention 11, 191 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dao TL, Ip C, Patel JK & Kishore GS Serum and tumor sialyltransferase activities in women with breast cancer. Progress in Clinical & Biological Research 204, 31 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berge PG, Wilhelm A, Schriewer H & Wust G Serum-sialyltransferase activity in cancer patients. Klin Wochenschr 60, 445–449 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiser MM & Wilson JR Serum levels of glycosyltransferases and related glycoproteins as indicators of cancer: biological and clinical implications. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 14, 189–239 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wandall HH, et al. The origin and function of platelet glycosyltransferases. Blood 120, 626–635 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manhardt CT, Punch PR, Dougher CWL & Lau JTY Extrinsic sialylation is dynamically regulated by systemic triggers in vivo. J Biol Chem 292, 13514–13520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee MM, et al. Platelets support extracellular sialylation by supplying the sugar donor substrate. J Biol Chem 289, 8742–8748 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irons EE, et al. B cells suppress medullary granulopoiesis by an extracellular glycosylation-dependent mechanism. Elife 8(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hait NC, et al. Extracellular sialyltransferase st6gal1 in breast tumor cell growth and invasiveness. Cancer Gene Ther (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, et al. Transfer of Functional Cargo in Exomeres. Cell Rep 27, 940–954 e946 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirata T, et al. N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-V (GnT-V)-enriched small extracellular vesicles mediate N-glycan remodeling in recipient cells. iScience 26, 105747 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baccin C, et al. Combined single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal the molecular, cellular and spatial bone marrow niche organization. Nat Cell Biol 22, 38–48 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schweitzer KM, et al. Constitutive expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells of hematopoietic tissues. Am J Pathol 148, 165–175 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sipkins DA, et al. In vivo imaging of specialized bone marrow endothelial microdomains for tumour engraftment. Nature 435, 969–973 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haraldsen G, Kvale D, Lien B, Farstad IN & Brandtzaeg P Cytokine-regulated expression of E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in human microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 156, 2558–2565 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Schor KS, Sandmaier BM & Sackstein R differential L-selectin binding activities of human hematopoietic cell L-selectin ligands, HCELL and PSGL-1. J Biol Chem 276, 47623–47631 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dimitroff CJ, Lee JY, Fuhlbrigge RC & Sackstein R A distinct glycoform of CD44 is an L-selectin ligand on human hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 13841–13846 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sackstein R, et al. Ex vivo glycan engineering of CD44 programs human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell trafficking to bone. Nat Med 14, 181–187 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nasirikenari M, Veillon L, Collins CC, Azadi P & Lau JT Remodeling of marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells by non-self ST6Gal-1 sialyltransferase. J Biol Chem 289, 7178–7189 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giannini S, et al. beta4GALT1 controls beta1 integrin function to govern thrombopoiesis and hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nat Commun 11, 356 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang N, Lin S, Cui W & Newman PJ Overlapping and unique substrate specificities of ST3GAL1 and 2 during hematopoietic and megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood Adv 6, 3945–3955 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee-Sundlov MM, et al. Immune cells surveil aberrantly sialylated O-glycans on megakaryocytes to regulate platelet count. Blood 138, 2408–2424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chow A, et al. CD169(+) macrophages provide a niche promoting erythropoiesis under homeostasis and stress. Nat Med 19, 429–436 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petitpas K, et al. Genetic modifications designed for xenotransplantation attenuate sialoadhesin-dependent binding of human erythrocytes to porcine macrophages. Xenotransplantation 29, e12780 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bai J, et al. CD169-CD43 interaction is involved in erythroblastic island formation and erythroid differentiation. Haematologica 108, 2205–2217 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rughetti A, et al. Regulated expression of MUC1 epithelial antigen in erythropoiesis. Br J Haematol 120, 344–352 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rusiniak ME, et al. Extracellular ST6GAL1 regulates monocyte-macrophage development and survival. Glycobiology 32, 701–711 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Videira PA, et al. Surface alpha 2–3- and alpha 2–6-sialylation of human monocytes and derived dendritic cells and its influence on endocytosis. Glycoconj J 25, 259–268 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grabovsky V, et al. Subsecond induction of alpha4 integrin clustering by immobilized chemokines stimulates leukocyte tethering and rolling on endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 under flow conditions. J Exp Med 192, 495–506 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dougher CWL, et al. The blood-borne sialyltransferase ST6Gal-1 is a negative systemic regulator of granulopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol 102, 507–516 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nasirikenari M, Segal BH, Ostberg JR, Urbasic A & Lau JT Altered granulopoietic profile and exaggerated acute neutrophilic inflammation in mice with targeted deficiency in the sialyltransferase ST6Gal I. Blood 108, 3397–3405 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones MB, et al. Role for hepatic and circulatory ST6Gal-1 sialyltransferase in regulating myelopoiesis. J Biol Chem 285, 25009–25017 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nasirikenari M, et al. Recombinant Sialyltransferase Infusion Mitigates Infection-Driven Acute Lung Inflammation. Front Immunol 10, 48 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nasirikenari M, et al. Altered eosinophil profile in mice with ST6Gal-1 deficiency: an additional role for ST6Gal-1 generated by the P1 promoter in regulating allergic inflammation. J Leukoc Biol 87, 457–466 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gauthier L, Rossi B, Roux F, Termine E & Schiff C Galectin-1 is a stromal cell ligand of the pre-B cell receptor (BCR) implicated in synapse formation between pre-B and stromal cells and in pre-BCR triggering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 13014–13019 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rossi B, Espeli M, Schiff C & Gauthier L Clustering of pre-B cell integrins induces galectin-1-dependent pre-B cell receptor relocalization and activation. J Immunol 177, 796–803 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Irons EE & Lau JTY Systemic ST6Gal-1 Is a Pro-survival Factor for Murine Transitional B Cells. Front Immunol 9, 2150 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Irons EE, Punch PR & Lau JTY Blood-Borne ST6GAL1 Regulates Immunoglobulin Production in B Cells. Front Immunol 11, 617 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nanetti L, et al. Sialic acid and sialidase activity in acute stroke. Dis Markers 25, 167–173 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klei TRL, et al. Glycophorin-C sialylation regulates Lu/BCAM adhesive capacity during erythrocyte aging. Blood Adv 2, 14–24 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hanson VA, Shettigar UR, Loungani RR & Nadijcka MD Plasma sialidase activity in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 114, 59–63 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grewal PK, et al. The Ashwell receptor mitigates the lethal coagulopathy of sepsis. Nat Med 14, 648–655 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jaskiewicz E, Jodlowska M, Kaczmarek R & Zerka A Erythrocyte glycophorins as receptors for Plasmodium merozoites. Parasit Vectors 12, 317 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duraisingh MT, Maier AG, Triglia T & Cowman AF Erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 mediates invasion in Plasmodium falciparum utilizing sialic acid-dependent and -independent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 4796–4801 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bharara R, Singh S, Pattnaik P, Chitnis CE & Sharma A Structural analogs of sialic acid interfere with the binding of erythrocyte binding antigen-175 to glycophorin A, an interaction crucial for erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 138, 123–129 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dankwa S, et al. Genetic Evidence for Erythrocyte Receptor Glycophorin B Expression Levels Defining a Dominant Plasmodium falciparum Invasion Pathway into Human Erythrocytes. Infect Immun 85(2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jiang L, Duriseti S, Sun P & Miller LH Molecular basis of binding of the Plasmodium falciparum receptor BAEBL to erythrocyte receptor glycophorin C. Mol Biochem Parasitol 168, 49–54 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dankwa S, et al. Ancient human sialic acid variant restricts an emerging zoonotic malaria parasite. Nat Commun 7, 11187 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chou HH, et al. Inactivation of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase occurred prior to brain expansion during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 11736–11741 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang YX, et al. Restoring the youth of aged red blood cells and extending their lifespan in circulation by remodelling membrane sialic acid. J Cell Mol Med 20, 294–301 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vaysse J, Gattegno L, Bladier D & Aminoff D Adhesion and erythrophagocytosis of human senescent erythrocytes by autologous monocytes and their inhibition by beta-galactosyl derivatives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83, 1339–1343 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Qadri SM, Donkor DA, Nazy I, Branch DR & Sheffield WP Bacterial neuraminidase-mediated erythrocyte desialylation provokes cell surface aminophospholipid exposure. Eur J Haematol 100, 502–510 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aminoff D, Bell WC & VorderBruegge WG Cell surface carbohydrate recognition and the viability of erythrocytes in circulation. Prog Clin Biol Res 23, 569–581 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aminoff D, Bell WC, Fulton I & Ibgebrigtsen N Effect of sialidase on the viability of erythrocytes in circulation. Am J Hematol 1, 419–432 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Josefsson EC, Gebhard HH, Stossel TP, Hartwig JH & Hoffmeister KM The macrophage alphaMbeta2 integrin alphaM lectin domain mediates the phagocytosis of chilled platelets. J Biol Chem 280, 18025–18032 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hoffmeister KM, et al. The clearance mechanism of chilled blood platelets. Cell 112, 87–97 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Babic AM, et al. In vitro function and phagocytosis of galactosylated platelet concentrates after long-term refrigeration. Transfusion 47, 442–451 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hoffmeister KM, et al. Glycosylation restores survival of chilled blood platelets. Science 301, 1531–1534 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wandall HH, et al. Galactosylation does not prevent the rapid clearance of long-term, 4 degrees C-stored platelets. Blood 111, 3249–3256 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sorensen AL, et al. Role of sialic acid for platelet life span: exposure of beta-galactose results in the rapid clearance of platelets from the circulation by asialoglycoprotein receptor-expressing liver macrophages and hepatocytes. Blood 114, 1645–1654 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grozovsky R, et al. The Ashwell-Morell receptor regulates hepatic thrombopoietin production via JAK2-STAT3 signaling. Nat Med 21, 47–54 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Holdbrooks AT, Ankenbauer KE, Hwang J & Bellis SL Regulation of inflammatory signaling by the ST6Gal-I sialyltransferase. PLoS One 15, e0241850 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Allendorf DH, Franssen EH & Brown GC Lipopolysaccharide activates microglia via neuraminidase 1 desialylation of Toll-like Receptor 4. J Neurochem 155, 403–416 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu Y, Ren D & Chen GY Siglec-E Negatively Regulates the Activation of TLR4 by Controlling Its Endocytosis. J Immunol 197, 3336–3347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sieve I, et al. A positive feedback loop between IL-1beta, LPS and NEU1 may promote atherosclerosis by enhancing a pro-inflammatory state in monocytes and macrophages. Vascul Pharmacol 103–105, 16–28 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Deng X, Zhang J, Liu Y, Chen L & Yu C TNF-alpha regulates the proteolytic degradation of ST6Gal-1 and endothelial cell-cell junctions through upregulating expression of BACE1. Sci Rep 7, 40256 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Holdbrooks AT, Britain CM & Bellis SL ST6Gal-I sialyltransferase promotes tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-mediated cancer cell survival via sialylation of the TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) death receptor. J Biol Chem 293, 1610–1622 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu Z, et al. ST6Gal-I regulates macrophage apoptosis via alpha2–6 sialylation of the TNFR1 death receptor. J Biol Chem 286, 39654–39662 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cabral MG, et al. The phagocytic capacity and immunological potency of human dendritic cells is improved by alpha2,6-sialic acid deficiency. Immunology 138, 235–245 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Silva Z, et al. MHC Class I Stability is Modulated by Cell Surface Sialylation in Human Dendritic Cells. Pharmaceutics 12(2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Crespo HJ, et al. Effect of sialic acid loss on dendritic cell maturation. Immunology 128, e621–631 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lynch K, et al. Regulating Immunogenicity and Tolerogenicity of Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells through Modulation of Cell Surface Glycosylation by Dexamethasone Treatment. Front Immunol 8, 1427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stamatos NM, et al. LPS-induced cytokine production in human dendritic cells is regulated by sialidase activity. J Leukoc Biol 88, 1227–1239 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.de Oliveira Formiga R, et al. Neuraminidase is a host-directed approach to regulate neutrophil responses in sepsis and COVID-19. Br J Pharmacol 180, 1460–1481 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Abdulkhalek S, et al. Neu1 sialidase and matrix metalloproteinase-9 cross-talk is essential for Toll-like receptor activation and cellular signaling. J Biol Chem 286, 36532–36549 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Feng C, et al. Endogenous PMN sialidase activity exposes activation epitope on CD11b/CD18 which enhances its binding interaction with ICAM-1. J Leukoc Biol 90, 313–321 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sakarya S, et al. Mobilization of neutrophil sialidase activity desialylates the pulmonary vascular endothelial surface and increases resting neutrophil adhesion to and migration across the endothelium. Glycobiology 14, 481–494 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cross AS, et al. Recruitment of murine neutrophils in vivo through endogenous sialidase activity. J Biol Chem 278, 4112–4120 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Theruvath J, et al. Anti-GD2 synergizes with CD47 blockade to mediate tumor eradication. Nat Med 28, 333–344 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Friedman DJ, et al. ST8Sia6 Promotes Tumor Growth in Mice by Inhibiting Immune Responses. Cancer Immunol Res 9, 952–966 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Vijayan M, et al. Decidual glycodelin-A polarizes human monocytes into a decidual macrophage-like phenotype through Siglec-7. J Cell Sci 133(2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Beatson R, et al. Cancer-associated hypersialylated MUC1 drives the differentiation of human monocytes into macrophages with a pathogenic phenotype. Commun Biol 3, 644 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Higuchi H, Shoji T, Iijima S & Nishijima K Constitutively expressed Siglec-9 inhibits LPS-induced CCR7, but enhances IL-4-induced CD200R expression in human macrophages. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 80, 1141–1148 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Beatson R, et al. The mucin MUC1 modulates the tumor immunological microenvironment through engagement of the lectin Siglec-9. Nat Immunol 17, 1273–1281 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rodriguez E, et al. Sialic acids in pancreatic cancer cells drive tumour-associated macrophage differentiation via the Siglec receptors Siglec-7 and Siglec-9. Nat Commun 12, 1270 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kano F, Matsubara K, Ueda M, Hibi H & Yamamoto A Secreted Ectodomain of Sialic Acid-Binding Ig-Like Lectin-9 and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Synergistically Regenerate Transected Rat Peripheral Nerves by Altering Macrophage Polarity. Stem Cells 35, 641–653 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ito T, et al. Secreted Ectodomain of SIGLEC-9 and MCP-1 Synergistically Improve Acute Liver Failure in Rats by Altering Macrophage Polarity. Sci Rep 7, 44043 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Matsumoto T, et al. Soluble Siglec-9 suppresses arthritis in a collagen-induced arthritis mouse model and inhibits M1 activation of RAW264.7 macrophages. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 133 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu H, et al. Immunosuppressive Siglec-E ligands on mouse aorta are up-regulated by LPS via NF-kappaB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 122, 109760 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang Y, et al. Immunoregulatory Siglec ligands are abundant in human and mouse aorta and are up-regulated by high glucose. Life Sci 216, 189–199 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mitsuki M, et al. Siglec-7 mediates nonapoptotic cell death independently of its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs in monocytic cell line U937. Glycobiology 20, 395–402 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Patras KA, et al. Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein engages human Siglec-9 to modulate neutrophil activation in the urinary tract. Immunol Cell Biol 95, 960–965 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Secundino I, et al. Host and pathogen hyaluronan signal through human siglec-9 to suppress neutrophil activation. J Mol Med (Berl) 94, 219–233 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jia Y, et al. Expression of ligands for Siglec-8 and Siglec-9 in human airways and airway cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 135, 799–810 e797 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Khatua B, Bhattacharya K & Mandal C Sialoglycoproteins adsorbed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa facilitate their survival by impeding neutrophil extracellular trap through siglec-9. J Leukoc Biol 91, 641–655 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Carlin AF, et al. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood 113, 3333–3336 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lizcano A, et al. Erythrocyte sialoglycoproteins engage Siglec-9 on neutrophils to suppress activation. Blood 129, 3100–3110 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.von Gunten S, et al. Siglec-9 transduces apoptotic and nonapoptotic death signals into neutrophils depending on the proinflammatory cytokine environment. Blood 106, 1423–1431 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zeng Z, et al. Increased expression of Siglec-9 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci Rep 7, 10116 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Saito M, et al. A soluble form of Siglec-9 provides a resistance against Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection in transgenic mice. Microb Pathog 99, 106–110 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.O’Sullivan JA, Chang AT, Youngblood BA & Bochner BS Eosinophil and mast cell Siglecs: From biology to drug target. J Leukoc Biol 108, 73–81 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gonzalez-Gil A, et al. Sialylated keratan sulfate proteoglycans are Siglec-8 ligands in human airways. Glycobiology 28, 786–801 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kiwamoto T, et al. Mice deficient in the St3gal3 gene product alpha2,3 sialyltransferase (ST3Gal-III) exhibit enhanced allergic eosinophilic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133, 240–247 e241–243 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Carroll DJ, Cao Y, Bochner BS & O’Sullivan JA Siglec-8 Signals Through a Non-Canonical Pathway to Cause Human Eosinophil Death In Vitro. Front Immunol 12, 737988 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Carroll DJ, et al. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 (Siglec-8) is an activating receptor mediating beta(2)-integrin-dependent function in human eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol 141, 2196–2207 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kano G, Bochner BS & Zimmermann N Regulation of Siglec-8-induced intracellular reactive oxygen species production and eosinophil cell death by Src family kinases. Immunobiology 222, 343–349 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Na HJ, Hudson SA & Bochner BS IL-33 enhances Siglec-8 mediated apoptosis of human eosinophils. Cytokine 57, 169–174 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kano G, Almanan M, Bochner BS & Zimmermann N Mechanism of Siglec-8-mediated cell death in IL-5-activated eosinophils: role for reactive oxygen species-enhanced MEK/ERK activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 132, 437–445 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Nutku-Bilir E, Hudson SA & Bochner BS Interleukin-5 priming of human eosinophils alters siglec-8 mediated apoptosis pathways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 38, 121–124 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nutku E, Hudson SA & Bochner BS Mechanism of Siglec-8-induced human eosinophil apoptosis: role of caspases and mitochondrial injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336, 918–924 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Muller J, et al. CD22 ligand-binding and signaling domains reciprocally regulate B-cell Ca2+ signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 12402–12407 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hennet T, Chui D, Paulson JC & Marth JD Immune regulation by the ST6Gal sialyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 4504–4509 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Poe JC, et al. CD22 regulates B lymphocyte function in vivo through both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent mechanisms. Nat.Immunol. 5, 1078 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ghosh S, Bandulet C & Nitschke L Regulation of B cell development and B cell signalling by CD22 and its ligands {alpha}2,6-linked sialic acids. Int Immunol, 603–611 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Campbell MA & Klinman NR Phosphotyrosine-dependent association between CD22 and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1C. Eur J Immunol 25, 1573–1579 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Collins BE, Smith BA, Bengtson P & Paulson JC Ablation of CD22 in ligand-deficient mice restores B cell receptor signaling. Nat Immunol 7, 199–206 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Santos L, et al. Dendritic cell-dependent inhibition of B cell proliferation requires CD22. J Immunol 180, 4561–4569 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Otipoby KL, et al. CD22 regulates thymus-independent responses and the lifespan of B cells. Nature 384, 634 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Sato S, et al. CD22 is both a positive and negative regulator of B lymphocyte antigen receptor signal transduction: altered signaling in CD22-deficient mice. Immunity 5, 551 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.O’Reilly MK, Tian H & Paulson JC CD22 is a recycling receptor that can shuttle cargo between the cell surface and endosomal compartments of B cells. J Immunol 186, 1554–1563 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tateno H, et al. Distinct endocytic mechanisms of CD22 (Siglec-2) and Siglec-F reflect roles in cell signaling and innate immunity. Mol Cell Biol 27, 5699–5710 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Han S, Collins BE, Bengtson P & Paulson JC Homomultimeric complexes of CD22 in B cells revealed by protein-glycan cross-linking. Nat Chem Biol 1, 93–97 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Gasparrini F, et al. Nanoscale organization and dynamics of the siglec CD22 cooperate with the cytoskeleton in restraining BCR signalling. EMBO J 35, 258–280 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Courtney AH, Bennett NR, Zwick DB, Hudon J & Kiessling LL Synthetic antigens reveal dynamics of BCR endocytosis during inhibitory signaling. ACS Chem Biol 9, 202–210 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Gross AJ, Lyandres JR, Panigrahi AK, Prak ET & DeFranco AL Developmental acquisition of the Lyn-CD22-SHP-1 inhibitory pathway promotes B cell tolerance. J Immunol 182, 5382–5392 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Danzer CP, Collins BE, Blixt O, Paulson JC & Nitschke L Transitional and marginal zone B cells have a high proportion of unmasked CD22: implications for BCR signaling. Int Immunol 15, 1137–1147 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Irons EE & Lau JTY Systemic ST6Gal-1 Is a Pro-survival Factor for Murine Transitional B Cells. Front Immunol 9, 2150 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Toda M, et al. Ligation of tumour-produced mucins to CD22 dramatically impairs splenic marginal zone B-cells. Biochem J 417, 673–683 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Gerlach J, et al. B cell defects in SLP65/BLNK-deficient mice can be partially corrected by the absence of CD22, an inhibitory coreceptor for BCR signaling. Eur J Immunol 33, 3418–3426 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Samardzic T, et al. CD22 regulates early B cell development in BOB.1/OBF.1-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol 32, 2481–2489 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Karlsson MC & Ravetch JV Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 19571–19578 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F & Ravetch JV Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science 313, 670–673 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Anthony RM, Kobayashi T, Wermeling F & Ravetch JV Intravenous gammaglobulin suppresses inflammation through a novel T(H)2 pathway. Nature 475, 110–113 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Jones MB, et al. B-cell-independent sialylation of IgG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 7207–7212 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Oswald DM, et al. ST6Gal1 in plasma is dispensable for IgG sialylation. Glycobiology 32, 803–813 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Glendenning LM, Zhou JY, Reynero KM & Cobb BA Divergent Golgi trafficking limits B cell-mediated IgG sialylation. J Leukoc Biol 112, 1555–1566 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Glendenning LM, et al. Platelet-localized ST6Gal1 does not impact IgG sialylation. Glycobiology (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Erickson JJ, et al. Pregnancy enables antibody protection against intracellular infection. Nature 606, 769–775 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Liu Y, et al. Plasma ST6GAL1 regulates IgG sialylation to control IgA nephropathy progression. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 12, 20406223211048644 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Shade KC, et al. Sialylation of immunoglobulin E is a determinant of allergic pathogenicity. Nature 582, 265–270 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Jenner J, Kerst G, Handgretinger R & Muller I Increased alpha2,6-sialylation of surface proteins on tolerogenic, immature dendritic cells and regulatory T cells. Exp Hematol 34, 1212–1218 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Starr TK, Daniels MA, Lucido MM, Jameson SC & Hogquist KA Thymocyte sensitivity and supramolecular activation cluster formation are developmentally regulated: a partial role for sialylation. J Immunol 171, 4512–4520 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Moody AM, et al. Sialic acid capping of CD8beta core 1-O-glycans controls thymocyte-major histocompatibility complex class I interaction. J Biol Chem 278, 7240–7246 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Daniels MA, et al. CD8 binding to MHC class I molecules is influenced by T cell maturation and glycosylation. Immunity 15, 1051–1061 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Jouanneau E, et al. Intrinsically de-sialylated CD103(+) CD8 T cells mediate beneficial anti-glioma immune responses. Cancer Immunol Immunother 63, 911–924 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Kao C, Sandau MM, Daniels MA & Jameson SC The sialyltransferase ST3Gal-I is not required for regulation of CD8-class I MHC binding during T cell development. J Immunol 176, 7421–7430 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Hernandez JD, Klein J, Van Dyken SJ, Marth JD & Baum LG T-cell activation results in microheterogeneous changes in glycosylation of CD45. Int Immunol 19, 847–856 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]