Abstract

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) is unique relative to all known animal viruses, especially in terms of its ability to redirect host RNA polymerase(s) to transcribe its 1,679-nucleotide (nt) circular RNA genome. During replication there accumulates not only more molecules of the genome but also its exact complement, the antigenome. In addition, there are relatively smaller amounts of an 800-nt RNA of antigenomic polarity that is polyadenylated and considered to act as mRNA for translation of the single and essential HDV protein, the delta antigen. Characterization of this mRNA could provide insights into the in vivo mechanism of HDV RNA-directed RNA transcription and processing. Previously, we showed that the 5′ end of this RNA was located in the majority of species, at nt 1630. The present studies show that (i) at least some of this RNA, as extracted from the liver of an HDV-infected woodchuck, behaved as if it contained a 5′-cap structure; (ii) in the infected liver there were additional polyadenylated antigenomic HDV RNA species with 5′ ends located at least 202 nt and even 335 nt beyond the nt 1630 site, (iii) the 5′ end at nt 1630 was not detected in transfected cells, following DNA-directed HDV RNA transcription, in the absence of genome replication, and (iv) nevertheless, using in vitro transcription with purified human RNA polymerase II holoenzyme and genomic RNA template, we did not detect initiation of template-dependent RNA synthesis; we observed only low levels of 3′-end addition to the template. These new findings support the interpretation that the 5′ end detected at nt 1630 during HDV replication represents a specific site for the initiation of an RNA-directed RNA synthesis, which is then modified by capping.

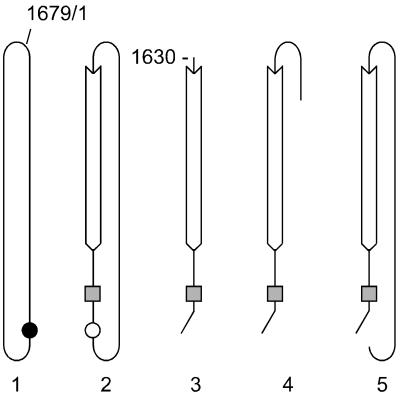

The two major species of RNA that accumulate during hepatitis delta virus (HDV) replication are the unit-length genome and its exact complement, the antigenome (Fig. 1, panels 1 and 2) (2). These 1,679-nucleotide (nt) RNAs are detected in both circular and linear forms. In addition, there are relatively smaller amounts of an 800-nt polyadenylated RNA of antigenomic polarity (Fig. 1, panel 3). This putative mRNA contains the open reading frame for the small delta protein, a 195-amino-acid species that is essential for HDV genome replication (10). All other proteins needed for HDV genome replication are provided by the host cell. This means that somehow a host RNA polymerase that is normally DNA dependent has to be redirected to act on HDV RNA as template.

FIG. 1.

HDV RNAs and strategy to detect in vivo processing of DNA-directed RNA transcripts that are antigenomic and polyadenylated. Panels 1 to 3 represent the genome, antigenome, and putative mRNA species, respectively, with features as previously described (2, 24). The closed and open circles represent the sites of genomic and antigenomic ribozyme cleavage, respectively. The shaded square represents the polyadenylation signal that is present on both the antigenomic RNA and the putative mRNA. The open arrow shows the limits of the open reading frame for the small form of the delta antigen. On panel 1 is indicated the origin of the numbering system (1679/1), based on the sequence of Kuo et al. (11). On panel 3 is indicated the previously determined 5′ end of the mRNA at nt 1630 (6). Panel 4 is a representation of a polyadenylated RNA with its 5′ end beyond nt 1630. Panel 5 presents the polyadenylated antigenomic RNA transcribed from pSG211, a pSVL construct transfected into Huh7 cells. This processed RNA should contain some pSVL sequences at the 5′ end (not indicated) and use the HDV polyadenylation signal at the 3′ end. As described in Materials and Methods, in terms of antigenomic HDV sequences, almost the entire 1,679 nt of the HDV antigenome is represented on this RNA.

One approach to clarify the mechanism of HDV genome replication with its unique RNA-directed RNA synthesis and processing has been to adopt the rationale that a detailed characterization of the mRNA species will provide valuable insights. Previous studies include (i) Northern analyses (2), (ii) primer extension (9), (iii) ribonuclease protection assays (27), and (iv) 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′-RACE) (6). By primer extension, a 5′ end was first mapped to position 1631 ± 1 of the 1,679-nt RNA sequence (9). A more recent study using 5′-RACE indicated position 1630 (6).

We and others, in attempts to understand HDV genome replication, have previously considered the hypothesis that the 5′ end is an initiation site for RNA-directed RNA synthesis (1, 23). An associated hypothesis is that by nucleotide sequence and/or structure, a proximal element exists that acts as a promoter for transcription (1). This second hypothesis has been extended to suggest that a double-stranded DNA corresponding in sequence to this region of the HDV genome will function as a promoter for DNA-directed RNA synthesis by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) (1, 15). In fact, more experiments are needed to test the validity of these hypotheses. Even the concept that in vivo HDV RNA-directed RNA transcription is mediated by the host Pol II remains tentative (4, 5, 16, 22, 24).

In a recent study we used 5′-RACE to determine the location of the 5′ ends of the mRNA under several different conditions of HDV replication. We found the predominant location to be nt 1630. Furthermore, when the HDV was subjected to prior mutagenesis by nucleotide changes, it was possible to find genome replication that was associated with mRNAs containing either a different 5′ end or even a spectrum of 5′ ends (6). These studies left open the question of whether nt 1630 and the other 5′ ends represented sites of initiation or the consequences of some form of endonucleolytic processing. In terms of the latter possibility there are precedents of stable polyadenylated RNA species whose 5′ ends are uncapped and arise via site-specific posttranscriptional endonucleolytic cleavage (17, 25).

In the present paper, we describe four studies that allow us to distinguish between some of the hypotheses mentioned above. The first study addresses whether the mRNA has a 5′-cap structure at nt 1630. The second considers whether there are also 5′ ends beyond nt 1630. The third examines the role of genome replication in 5′-end formation. The final study is an attempt to reconstitute initiation of transcription in vitro using Pol II.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Most plasmids used, such as pTW101, have been previously described (30). pDL553 is a construct based on pSVL (Pharmacia), which expresses 1.2 copies of HDV genomic RNA (30). pDL542 is similar to pDL553 except for a 2-nt deletion at position 1434 to 1435 (12). pDL444 expresses the small form of the delta protein (13). pSG211, which expresses almost-full-length antigenomic HDV RNA, was constructed by insertion of the large PshAI-XbaI fragment of HDV at the SmaI and XbaI sites of pSVL.

Isolation of polyadenylated RNA isolated from liver of HDV-infected woodchuck.

A woodchuck chronically infected with woodchuck hepatitis virus was superinfected with HDV, and at 25 days, around the time of peak acute HDV infection, the animal was sacrificed (20). Total RNA was extracted from samples of liver using a guanidine isothiocyanate procedure involving a final centrifugation to equilibrium in the presence of added cesium chloride (3). Polyadenylated RNA was then selected by two passages over an oligo(dT)-cellulose column (6).

RNA transcription in vitro.

Large-scale transcription of 1.2× genomic RNA by T7 polymerase and subsequent gel purification were conducted using a previously described procedure (7). The DNA template was plasmid pTW101 (30).

Transfections.

For most transfections we used Huh7 cells (19), cDNA constructs, and Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies) or FuGENE 6 (Roche). However, for transfections with RNA transcribed in vitro, we used Lipofectamine Plus (Life Technologies) and a special line of Huh7 cells stably expressing the small form of the delta protein (provided by T.-T. Wu).

RNA extraction from transfected cells.

Total RNA was extracted using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center).

Analyses of HDV RNAs.

Three different procedures were used to analyze the sequences on the antigenomic polyadenylated RNA. (i) RNA ligation-mediated (RLM)-RACE was carried out with a kit, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Ambion). As indicated in Fig. 2B, the adapter primers M and O were provided (Ambion) while the HDV-specific target primers P and N were as follows: P was 5′-CCGGCCACCCACTGCTCGAGGATCT located at nt 1531 to 1555 and N was 5′-GAGCCCCCTCTCCATCCTTATCC located at nt 1394 to 1416. (ii) Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) began with an RT step on RNAs immobilized to avidin-coated superparamagnetic beads (Dynal) via 5′-biotin-oligo(dT), after which PCR was carried out using pairs of primers as indicated in Fig. 3A. Primer P was as described above. Antigenomic primers Q to S were as follows: Q was 5′-AAGAGTACTGAGGACGGCCGCCTCTAGCCG located at nt 1630 to 1601, R was 5′-TTCTCCGGCGTTGTGGGGATCTCG located at nt 153 to 130, and S was 5′-TCCGAGTGGATTCCTCCCTCTGAGTGCTACTCAAC located at nt 286 to 252. (iii) 5′-RACE was carried out with a kit, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Clontech) but with modifications, as previously described (6). An additional modification was that the input RNA had already gone through two rounds of oligo(dT)-cellulose chromatography. As required, electrophoretic analysis of PCR products was carried out on gels of 3% agarose with TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate [pH 8.3], 1 mM EDTA), followed by staining with ethidium bromide. Also, cloning was carried out using a TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen) followed by automated DNA sequencing.

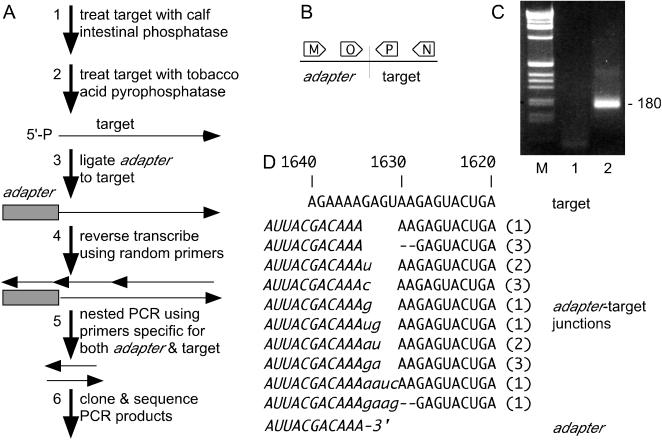

FIG. 2.

RLM-RACE analysis of polyadenylated HDV RNAs. (A) Summary of the six steps of the basic strategy applied to the polyadenylated RNA isolated from the liver of an infected woodchuck, as described in Results. (B) Representation of the nested PCR used in step 5. (C) Agarose gel analysis of three PCR products from step 5. Lane 1, a negative control, without added template; lane 2, the product obtained after steps 1 to 5; lane M, a 1-kb DNA ladder (Life Sciences). (D) Summary of the nucleotide sequence results for 18 adapter-target junctions obtained as in panel A, step 6, and using the product from panel C, lane 2. For comparison, we show the corresponding sequences for the antigenomic RNA and those for the 3′ end of the RNA adapter (italics). The lowercase letters indicate interpretations of insertions of 1 to 4 nt. These are considered to be due to a 3′ heterogeneity on the adapter RNA that arises during the synthesis by T7 polymerase (communication from Ambion, the kit manufacturer). The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of clones with the same junction sequence. For 5 of the 18 junctions, the original target was total RNA from the infected liver rather than the polyadenylated RNA.

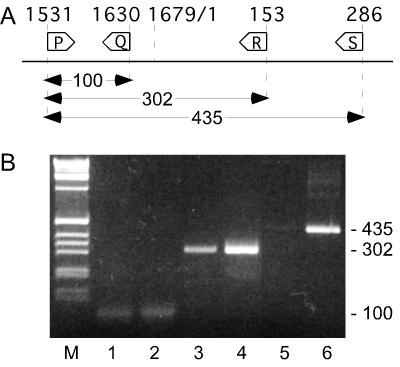

FIG. 3.

RT-PCR analysis of polyadenylated HDV RNAs. (A) Shown is the location, relative to the genomic sequence of HDV using the numbering of Kuo et al. (11), of 4 primers used in RT-PCR assays. (B) Lanes 1, 3, and 5, the RNA used was extracted from the liver of an HDV-infected woodchuck, and it was then selected twice by binding to oligo(dT)-cellulose before reverse transcription was carried out on RNAs immobilized to superparamagnetic beads via oligo(dT); lanes 2, 4, and 6, shown is a positive control of plasmid DNA (pDL553) containing HDV sequences that did not need to be reverse transcribed. The PCRs were carried out with primer pairs P-Q (lanes 1 and 2), P-R (lanes 3 and 4), and P-S (lanes 5 and 6). The products were separated by electrophoresis into 3% agarose. Lane M, a 1-kb DNA ladder. The PCR product sizes were consistent with the predictions from panel A, as indicated at the right.

In vitro transcription by Pol II.

One hundred nanograms of HDV genomic RNA (Fig. 4A), as transcribed in vitro, was adjusted to 50 mM BES (N, N-bis[2-hydroxyethyl]-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.2) and 10 mM MgCl2 and was heated at 50°C for 10 min. The sample of RNA template was then cooled down to room temperature and given a brief centrifugation. Human Pol II holoenzyme (28, 29), TATA-binding protein (TBP), and transcription buffer (as previously described [28], except for using 7 mM MgCl2) without ribonucleoside triphosphates were then added, in the presence or absence of actinomycin D (20 μg/ml), α-amanitin (2 μg/ml), or DNase I (1 U), and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Transcription was then initiated by adding 0.5 mM concentrations (each) of ATP, UTP, and GTP, 25 μM CTP, and 1 μCi of [α-32P]CTP. After incubation at 30°C for 1 h, the reactions were stopped and processed as described previously (28), except that glycogen (0.2 mg/ml) was used as the carrier for RNA precipitation. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried onto 3MM paper (Whatman), with radioactivity detected by autoradiography after a 4-day exposure at −80°C in the presence of an intensifying screen.

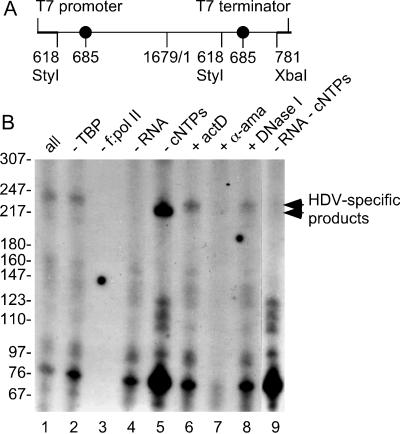

FIG. 4.

Ability of HDV genomic RNA to act in vitro as a template for RNA Pol II transcription. (A) HDV genomic RNA was transcribed from construct pTW101, which contains 1.2× HDV cDNA, inserted between a phage T7 RNA polymerase promoter and terminator. The numbering for HDV sites (thinner line) is from the sequence described by Kuo et al. (11). (B) The linear HDV genomic RNA was gel purified and used as a template for in vitro transcription in reaction mixtures containing human TBP, a preassembled human Pol II holoenzyme (f:pol II), [α-32P]CTP, and unlabeled (or cold) ribonucleoside triphosphates (cNTPs), in the absence (−) or presence (+) of actinomycin D (actD), α-amanitin (α-ama), or DNase I, as previously described (28). Individual components were then selectively omitted from the complete reaction mixture (all) as indicated (lanes 2 to 5 and 9). Reaction products were extracted and subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions, followed by autoradiography (28). For size markers, we used MspI fragments of pBR322 DNA that were 5′ labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The migration of some of these fragments is shown on the left and the HDV-specific products are indicted on the right. Lane 1, complete reaction mixture; lane 2, minus TBP; lane 3, minus Pol II holoenzyme; lane 4, minus HDV RNA; lane 5, minus unlabeled nucleoside triphosphates; lane 6, plus actinomycin D; lane 7, plus α-amanitin; lane 8, plus DNase I; lane 9, minus unlabeled nucleoside triphosphates and HDV RNA.

RESULTS

Detection of a 5′ cap on polyadenylated antigenomic RNA from the infected liver.

A major question concerning the 5′ end of the putative HDV mRNA that arises by a unique mechanism of RNA-directed synthesis is whether this species is subsequently modified, like certain host DNA-directed transcripts, to receive a cap structure. This has been a difficult question to address because the amount of this mRNA is small, approximately 600 copies per cell in an infected liver (2). However, as now described, we found that the question could be answered with a novel procedure, referred to as RLM-RACE. The basic procedure is diagrammed in Fig. 2A. As target, we first isolated polyadenylated RNA from the liver of an HDV-infected woodchuck. In step 1, this RNA was treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) to remove all exposed 5′ phosphates, and then in step 2, the RNA was treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) to remove cap structures and leave behind 5′ monophosphates. In step 3, these newly exposed 5′ ends were ligated to a 151-nt RNA adapter. Next, in step 4, the RNA was reverse transcribed in the presence of added primers, and then in step 5, the cDNA product was used as template for a nested PCR, with primers as indicated in Fig. 2B. A gel analysis of the final inner PCR products is shown in Fig. 2C. Lane 1 represents a reaction performed in the absence of added template. Lane 2 corresponds to product made from RNA using steps 1 to 5. In lane 2, we detected a major band of about 180 bp. Such a band was not detected in the absence of the TAP treatment or in the absence of both CIP and TAP treatments (data not shown). Next, the total product in lane 2 was cloned and sequenced. The sequences of 18 clones are summarized in Fig. 2D. After allowances for repeat isolations of the same sequence, there are actually 10 unique sequences. These differences reflect either variations in the 5′ end of the RNA target or the 3′ end of the adapter. (For more details, see the legend to Fig. 2). For each sequence, we show only one interpretation of the adapter-target junction, although in some cases there are other interpretations. Collectively, these data indicate that the capped 5′ ends of the target RNAs must be located in the region of nt 1631 to 1628. However, we note that a more specific interpretation is that the majority of the sequenced junctions are consistent with a capped target RNA beginning at nt 1630, along with a less frequent site at nt 1628.

In a modification of this RLM-RACE procedure, we omitted the CIP and TAP treatments for the target RNA. This variation would be able to detect a target RNA that already had a 5′ monophosphate, but in fact, none were found (data not shown). Neither the original procedure nor this modified procedure would have detected RNAs whose 5′-end group was a hydroxyl, diphosphate, or triphosphate. Overall, our interpretation is that the polyadenylated antigenomic RNAs, at least for 5′ ends in the vicinity of nt 1630, have primarily a cap structure rather than a 5′ monophosphate.

5′ ends at sites beyond nt 1630.

The following experiments were undertaken to determine whether there might be at least a minor population of polyadenylated RNAs with 5′ ends much beyond nt 1630 (Fig. 1, panel 4). Just the detection of such species would be proof that there are sites beyond nt 1630 on the genomic RNA template at which polyadenylated RNAs are initiated.

We used a novel RT-PCR strategy, other than RLM-RACE, to search for such species. The polyadenylated RNA from the infected liver was first isolated and then reverse transcribed using an oligo(dT) primer to obtain cDNA. Then, for PCR, we used three pairs of primers, P-Q, P-R, and P-S, as shown in Fig. 3A. With this strategy, the detection of a PCR product is an indication of polyadenylated RNAs with 5′ ends at or beyond positions nt 1630, 153, and 286, respectively. The results are shown in Fig. 3B, lanes 1, 3, and 5, respectively. As a positive control, we carried out amplification of HDV cDNA in parallel reactions using the same primer pairs, as shown in lanes 2, 4, and 6, respectively, and detected products consistent with the expectations of 100, 302, and 435 bp, respectively. The polyadenylated RNA from infected liver produced bands corresponding to 100 bp (lane 1) and 302 bp (lane 3) and barely detectable amounts of 435 bp (lane 5). The HDV-specific identities of both the 302- and 435-bp products were confirmed by cloning and nucleotide sequencing (data not shown).

Thus, we interpret that in the liver during a natural infection, some of the polyadenylated antigenomic RNAs extend to at least nt 153 and 286, even though we know from the previous 5′-RACE analyses that the major fraction extends only to nt 1630 (6). We also carried out experiments using not liver RNA but RNA from cells in which genome replication was initiated by transfection with either cDNA constructs or HDV RNA transcribed in vitro. Using primers P and R, we were again able to detect the correct HDV-specific PCR product (data not shown).

Although RT-PCR results can be subject to artifacts, there are several aspects of our experimental design which reduce this possibility. (i) The RNA used was initially selected twice by oligo(dT)-cellulose. (ii) The RT was primed by oligo(dT). (iii) The reverse transcriptase used was a deleted form, lacking RNase H activity. (iv) We were looking for species whose 5′ ends were actually beyond, rather than before, nt 1630. (v) Finally, we have confirmed the identity of the PCR products by cloning and nucleotide sequencing. One limitation, however, is that these RT-PCR assays did not give us independent quantitation of the fraction of molecules that proceed beyond nt 1630 relative to those that do not.

In summary, these results lead us to conclude that at least some of the polyadenylated antigenomic HDV RNAs are initiated at sites beyond nt 1630. While more experiments are needed to clarify the mechanism of such synthesis, our findings also open the possibility that species with 5′ ends beyond nt 1630 could also function as mRNA.

5′ ends in the vicinity of nt 1630.

In a previous study using 5′-RACE, it was found that the majority of 5′ ends for the polyadenylated RNA present during wild-type HDV genome replication were located at nt 1630 (Fig. 1, panel 3); however, minor amounts of other ends in the vicinity were also detected (6). Furthermore, when studying the replication of certain mutated genomes, we in some cases observed other 5′ ends; in fact, for one mutant, the majority of the 5′ ends was at nt 1642 (6). Because of these results we undertook even further experiments to determine the basis for the variety of detected 5′ ends.

An unexpected result was obtained when we examined the 5′ ends formed when genome replication was carried out in the presence of controlled amounts of delta protein. To achieve this, cells were cotransfected with a construct (pDL542) and mutated at a distant site (deletion of nt 1434 to 1435) that cannot make delta protein, along with a construct (pDL444) which acts as a controlled source of this protein. After 6 days, the total RNA was extracted and 5′-RACE was used, as previously reported (6), to determine the 5′ end of the polyadenylated antigenomic RNA. We found that 12 out of 23 sequenced clones had a 5′ end at nt 1630. However, 10 were at nt 1642 and 1 was at nt 1656.

These new results, along with the previous results for mutated HDV genomes (6), force us to address the question of the origin of the 5′ ends at locations other than nt 1630. One possibility is that, as we have concluded for nt 1630, they are also sites for the initiation of RNA-directed RNA synthesis. A second, quite different possibility is that they are the consequences of posttranscriptional endonucleolytic RNA cleavage. That is, they are RNA species that somehow were initiated at one or more upstream locations and subsequently were cleaved to produce the observed 5′ ends.

The following experiment was undertaken to determine whether, in the absence of HDV RNA-directed RNA synthesis, we could detect endonucleolytic cleavage of a polyadenylated antigenomic RNA. We designed the following construct (pSG211) by using the expression vector pSVL. In transfected cells, this DNA construct should be used by Pol II to transcribe RNAs which, after processing, should produce a hybrid mRNA that contains an simian virus 40-specific 5′ end followed by almost the complete antigenome of HDV and ending with polyadenylation directed by the HDV polyadenylation signal. Even in the presence of delta protein, this RNA cannot replicate but it should be able to fold into the rod-like structure typical of full-length antigenomic and genomic RNAs. The HDV sequences (without the vector sequences) of the processed RNA are schematically represented in Fig. 1, panel 5.

We waited until 9 days after transfection to increase the opportunity for endonucleolytic cleavage of the hybrid mRNA. Then, we extracted the RNAs and used the 5′-RACE procedure to examine the 5′ ends of the polyadenylated RNAs containing HDV antigenomic sequences. Eight out of eight sequenced clones indicated 5′ ends within the HDV sequences; two of these ends were at nt 1642, two were at nt 1654, 1 was at nt 1657, 1 was at nt 1657, 1 was at 1632, 1 was at nt 1638, and 1 was at nt 117. Since one might have expected the 5′ ends to be predominantly in the vector sequences, we tested, in parallel, RNAs from cells transfected with other constructs. For two constructs that contained the open reading frame for delta protein but no additional HDV sequences that would allow formation of rod-like folding (in the vicinity of the top of the rod), 15 out of 15 sequences indicated 5′ ends within vector sequences. As positive controls, two constructs capable of initiating genome replication indicated that 10 out of 10 5′ ends were at nt 1630.

From this experiment, it is important to note that of these 5′ ends determined for nonreplicating rod-like RNA, nt 1642 was found in the case of the mutant (pDL542), mentioned earlier. Furthermore, even for replication-competent mutant genomes previously reported (6), we have detected nt 1632, 1638, 1654, and 1657, along with nt 1642. Thus, we now have to allow that some or all of these 5′ ends may have arisen by endonucleolytic cleavage.

The present experiments have revealed that initiation is not the only way to get 5′ ends located other than at nt 1630. They can arise in the absence of any HDV RNA-directed RNA synthesis. We favor the interpretation that, at least in this particular case, they arose by posttranscriptional endonucleolytic cleavage of those DNA-directed RNA transcripts that were able to fold into the rod-like structure. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that they arose via DNA-directed initiation from what has been reported as a cryptic promoter in the double-stranded cDNA copy of this region of the HDV genome (1, 15).

Nevertheless, our experiments support two important conclusions regarding those 5′ ends that are at nt 1630. Such ends were not produced by posttranscriptional cleavage and were not DNA-directed initiations produced by the above-mentioned cryptic promoter.

Transcription by Pol II in vitro, using HDV genomic RNA as template.

The final experimental approach we used was to reexamine in vitro transcription by Pol II of HDV RNA species. We reasoned that if nt 1630 corresponds to an initiation site and if Pol II is responsible for such RNA-directed transcription, then it might be possible to recreate such synthesis in vitro, using a Pol II-dependent cell-free transcription system with HDV genomic RNA as template. An in vitro transcription system reconstituted with a preassembled human Pol II holoenzyme (f:pol II; see references 28 and 29) and a TATA-binding factor (TBP) was used, as it has been shown previously that this two-component system can efficiently and specifically produce RNA from DNA templates that contain promoters, such as those from adenovirus (28), human immunodeficiency virus (28), and human papillomavirus (8).

For these studies, we prepared a greater-than-unit-length genomic RNA template via transcription with T7 RNA polymerase utilizing the plasmid DNA diagrammed in Fig. 4A. This RNA was gel purified and then was used as a template for transcription by Pol II. As shown in Fig. 4B, an HDV-specific product of approximately 220 nt was detected in the presence of Pol II holoenzyme and TBP (compare lanes 1 and 4). Formation of this HDV product was dependent on Pol II holoenzyme, as omitting Pol II holoenzyme, but not TBP, from the complete reaction abolished the signals (lanes 1 to 3). That inclusion of α-amanitin, but not actinomycin D or DNase I, during the transcription reaction eliminated the signals (lanes 6 to 8) further indicates that this HDV-specific product was indeed generated by Pol II from HDV genomic RNA and was not derived from any DNA molecules, if present, in the reactions. When cold ribonucleoside triphosphates were left out of the complete reaction mixture, the signals from all the labeled species were enhanced (compare lanes 1 and 5), which suggested to us that these products were generated by the 3′-end-labeling activity of Pol II. Consistent with this interpretation, the size of the HDV-specific product, which was still detected in the reactions without cold ribonucleoside triphosphates (compare lanes 5 and 9), was slightly reduced (compare lanes 1 and 5). The HDV-specific product, therefore, likely represents a 3′-end-labeled fragment released from the 3′ end of the 2-kb RNA template by prior action of the HDV ribozyme.

It should be noted that even the HDV-specific end-labeled product was of very low abundance. It took 4 days to detect by autoradiography, which should be contrasted to transcription from a Pol II-directed DNA promoter, the products of which were usually detected in several hours (data not shown).

We also carried out Pol II transcription experiments in the absence of radioactive label, using glyoxalation, agarose gels, and Northern analysis to assay for reaction products. Other modifications included the use of trimers of HDV RNA and also with antigenomic rather than genomic RNA templates. None of these studies detected discrete-sized run-off RNA-directed species consistent with initiation at nt 1630 or any other location (data not shown).

In summary, in these studies using an in vitro Pol II system with clear competence for DNA-directed RNA synthesis, we were unable to detect initiation of RNA-directed RNA synthesis on an HDV RNA template. All that we detected could be described as short additions to the 3′ end of the template molecules.

DISCUSSION

One of the major questions for HDV replication has concerned whether the 5′ end detected at nt 1630 on the antigenomic polyadenylated RNA represents a site of initiation of RNA-directed RNA synthesis or a site of posttranscriptional endonucleolytic RNA processing (2, 6, 9, 14, 18). Here we provide three lines of evidence, which taken together, lead us to favor the first possibility. (i) By RLM-RACE, we obtained evidence that the 5′ end contains a cap structure (Fig. 2D). All known examples of RNA species that are capped in vivo, involve initiation to create 5′ ends with a triphosphate that is then converted to a cap structure. RLM-RACE is a very sensitive method but because it is indirect, we cannot comment on the presence or absence of cap-associated methylation modifications. It should be added that our studies did not detect 5′ ends at nt 1630 that contained a 5′ monophosphate and that the strategy used would not have been able to detect species with a 5′ hydroxyl or triphosphate. (ii) By 5′-RACE, we found that 5′ ends at nt 1630 were not just preferred but actually only detectable when genome replication was also occurring. (iii) For cells transfected with a DNA construct that expresses almost the entire antigenomic sequence as a nonreplicating polyadenylated RNA, we were unable to detect by 5′-RACE any ends at nt 1630. This also argues against an endonucleolytic cleavage mechanism.

If nt 1630 is a site of initiation, it seems reasonable to suggest that nearby some sequence and/or structural feature serves as a promoter. This idea has been the rationale behind several mutagenesis studies (1, 6, 30). However, some studies have gone so far as to examine double-stranded cDNA versions of HDV sequences from this region for such a putative promoter and have even reported such activity in transfected cells (1, 15). In contrast, our 5′-RACE data for antigenomic RNA expressed from a nonreplicating form of HDV cDNA did not detect nt 1630 as a 5′ end. Thus, we argue against the biological relevance to HDV of the cDNA promoter and consider the question of the mechanism of initiation of RNA-directed RNA synthesis still unresolved.

Our studies also show that there are also real but relatively minor amounts of polyadenylated antigenomic RNAs with 5′ ends that are located 202 nt and even 335 nt beyond 1630 (Fig. 3B). This allows us to conclude that, in a natural HDV infection, there are at least some sites other than nt 1630 for the initiation of polyadenylated HDV RNAs, even though we cannot say whether the RNAs we detected are capped or whether such RNAs have undergone an endonucleolytic cleavage.

As mentioned above, we were unable to detect any evidence for endonucleolytic cleavage at nt 1630. However, under conditions in which HDV replication was not occurring, we were able to obtain in vivo data consistent with endonucleolytic cleavage at other sites. Specifically, we used 5′-RACE to examine RNA from cells transfected with a cDNA construct designed to direct the synthesis of DNA-directed RNA transcripts that (i) were initiated in vector sequences, (ii) were followed by the almost-unit-length antigenome, and finally (iii) contained signals for polyadenylation. At 9 days after transfection, we detected polyadenylated RNAs with 5′ ends not as expected, in the vector sequences, but at a variety of locations within the HDV sequence. In some cases, the location was near to, but never at, nt 1630. Since in these experiments there is not even the genomic RNA template for RNA-directed RNA synthesis, our interpretation is that these particular 5′ ends arose via posttranscriptional endonucleolytic cleavage. This interpretation has implications for other studies in which RNA-directed RNA synthesis is occurring for either wild-type or mutated HDV, and we detected rare 5′ ends that are not at nt 1630. Previously we have pointed out that such ends have a preference for the 5′ nucleotide being adenosine or guanosine, indicative of sites of initiation by a host RNA polymerase (6). However, such indications are not sufficient, and maybe now we must allow that for each non-1630 end, additional data are needed to distinguish whether it arose via endonuclease action or initiation.

Returning to the question of nt 1630 as a site for the initiation of RNA-directed RNA synthesis, our in vivo data indicative of capping provoked us to attempt an in vitro reconstruction experiment. We used a system of proven competence for DNA-directed RNA synthesis by RNA Pol II. However, all we were able to detect in the presence of a genomic HDV RNA template was small amounts of 3′-end addition (Fig. 4B). In this respect, our results are similar to the previous reports of Beard et al. (1) and of Filipovska and Konarska (4). In the latter study, the observed 3′-end addition was to an antigenomic RNA template. Furthermore, the authors detected an endonucleolytic cleavage of the template, which also became a site for a short 3′-end addition. Overall, if Pol II really is the enzyme used by HDV for in vivo replication, and if nt 1630 is a site for initiation of transcription, then the in vitro studies must still lack some essential component or condition.

Clearly, still more studies are needed to explain the mechanism of HDV RNA-directed RNA synthesis. Maybe a serious problem is that in most of our assay systems we detected only those RNA species that accumulate: (i) the circular genome and antigenome species are more stable than the corresponding linear RNAs (21) and (ii) the HDV mRNA that is both polyadenylated at the 3′ end and 5′ capped at nt 1630 is now in possession of properties that offer survival advantages in a cell known to contain multiple exonuclease activities (26). The problem is that there may be many other linear HDV RNAs, genomic and antigenomic, that have 5′ ends created by initiation and/or endonucleolytic cleavage, but which because they are not protected, are less stable and thus less readily detected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-26522 and CA-06927 for J.T. and CA-81017 and GM-59643 for C.-M.C. Additional support was from an appropriation by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

At Fox Chase, we thank the DNA Synthesis Facility for providing the necessary oligonucleotides and Anita Cywinski of the DNA Sequencing Facility for the automated sequencing. Thanks also to Preetha Biswas, Jinhong Chang, Huan Zhou, and Vadim Bichko for their earlier efforts directed at in vitro transcription of HDV RNA templates. William Mason, Glenn Rall, Richard Katz, and Jinhong Chang gave constructive comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beard M R, Macnaughton T B, Gowans E J. Identification and characterization of a hepatitis delta virus RNA transcriptional promoter. J Virol. 1996;70:4986–4995. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4986-4995.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen P-J, Kalpana G, Goldberg J, Mason W, Werner B, Gerin J, Taylor J. Structure and replication of the genome of hepatitis δ virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8774–8778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chirgwin J, Przybyla A, MacDonald R, Rutter W. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filipovska J, Konarska M M. Specific HDV RNA-templated transcription by pol II in vitro. RNA. 2000;6:41–54. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu T-B, Taylor J. The RNAs of hepatitis delta virus are copied by RNA polymerase II in nuclear homogenates. J Virol. 1993;67:6965–6972. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.6965-6972.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gudima S, Dingle K, Wu T-T, Moraleda G, Taylor J. Characterization of the 5′ ends for polyadenylated RNAs synthesized during the replication of hepatitis delta virus. J Virol. 1999;73:6533–6539. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6533-6539.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudima S O, Kazantseva E G, Kostyuk D A, Shchaveleva I L, Grishchenko O I, Memelova L V, Kochetkov S N. Deoxyribonucleotide-containing RNAs: a novel class of templates for HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4614–4618. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou S Y, Wu S-Y, Zhou T, Thomas M C, Chiang C-M. Alleviation of human papillomavirus E2-mediated transcriptional repression via formation of a TATA binding protein (or TFIID)-TFIIB-RNA polymerase II-TFIIF preinitiation complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:115–125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.113-125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh S-Y, Chao M, Coates L, Taylor J. Hepatitis delta virus genome replication: a polyadenylated mRNA for delta antigen. J Virol. 1990;64:3192–3198. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3192-3198.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo M Y-P, Chao M, Taylor J. Initiation of replication of the human hepatitis delta virus genome from cloned DNA: role of delta antigen. J Virol. 1989;63:1945–1950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.1945-1950.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo M Y-P, Goldberg J, Coates L, Mason W, Gerin J, Taylor J. Molecular cloning of hepatitis delta virus RNA from an infected woodchuck liver: sequence, structure, and applications. J Virol. 1988;62:1855–1861. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.1855-1861.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazinski D W, Taylor J M. Expression of hepatitis delta virus RNA deletions: cis and trans requirements for self-cleavage, ligation, and RNA packaging. J Virol. 1994;68:2879–2888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2879-2888.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazinski D W, Taylor J M. Relating structure to function in the hepatitis delta virus antigen. J Virol. 1993;67:2672–2680. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2672-2680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo K, Hwang S B, Duncan R, Trousdale M, Lai M M C. Characterization of mRNA of hepatitis delta antigen: exclusion of full-length antigenomic RNA as an mRNA. Virology. 1998;250:94–105. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macnaughton T B, Beard M R, Chao M, Gowans E J, Lai M M C. Endogenous promoters can direct the transcription of hepatitis delta virus RNA from a recircularized cDNA template. Virology. 1993;196:629–636. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macnaughton T B, Gowans E J, McNamara S P, Burrell C J. Hepatitis delta antigen is necessary for access of hepatitis delta virus RNA to the cell transcriptional machinery but is not part of the transcriptional complex. Virology. 1991;184:387–390. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90855-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzlaff M, O'Dell M, Cluster P D, Flavell R B. RNA-mediated RNA degradation and chalcone synthase A silencing in petunia. Cell. 1997;88:845–854. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modahl L E, Lai M M C. Transcription of hepatitis delta antigen mRNA continues throughout hepatitis delta virus (HDV) replication: a new model of HDV RNA transcription and regulation. J Virol. 1998;72:5449–5456. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5449-5456.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakabayashi H, Taketa K, Miyano K, Yamane T, Sato J. Growth of human hepatoma cell lines with differentiated functions in chemically defined medium. Cancer Res. 1982;42:3858–3863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Netter H J, Wu T-T, Bockol M, Cywinski A, Ryu W-S, Tennant B C, Taylor J M. Nucleotide sequence stability of the genome of hepatitis delta virus. J Virol. 1995;69:1687–1692. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1687-1692.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puttaraju M, Been M. Generation of nuclease resistant circular RNA decoys for HIV-tat and HIV-rev by autocatalytic splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;33:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor J. HDV as a precedent for RNA-directed RNA synthesis by RNA polymerase II. In: Dinter-Gottlieb G, editor. The unique hepatitis delta virus. R.G. Austin, Tex: Landes, Co.; 1995. pp. 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor J. The structure and replication of hepatitis delta virus. Semin Virol. 1990;1:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor J M. Human hepatitis delta virus: structure and replication of the genome. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1999;239:108–122. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Dijk E L, Sussenbach J S, Holthuizen P E. Identification of RNA sequences and structures involved in site-specific cleavage of IGF-II mRNAs. RNA. 1998;4:1623–1635. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298981316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hoof A, Parker R. The exosome: a proteosome for RNA? Cell. 1999;12:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H-W, Wu H-L, Chen D-S, Chen P-J. Identification of the functional regions required for hepatitis D virus replication and transcription by linker-scanning mutagenesis of viral genome. Virology. 1997;239:119–131. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu S-Y, Chiang C-M. Properties of PC4 and an RNA polymerase II complex in directing activated and basal transcription in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12492–12498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu S-Y, Thomas M C, Hou S-Y, Likhite V, Chiang C-M. Isolation of mouse TFIID and functional characterization of TBP and TFIID in mediating estrogen receptor and chromatin transcription. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23480–23490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu T-T, Netter H J, Lazinski D W, Taylor J M. Effects of nucleotide changes on the ability of hepatitis delta virus to transcribe, process and accumulate unit-length, circular RNA. J Virol. 1997;71:5408–5414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5408-5414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]