Abstract

Graphene oxide (GO) and its derivatives have several applications in many areas such as environmental and energy materials, water treatment and biomedical technologies. Because of having various polar groups on its surface, GO is considered as an excellent adsorbent. However, for many applications such as adsorption of pollution from aqueous solutions, chemical functionalization of graphene oxide is often a necessary requirement. In the present study, a new composite from graphene oxide, diethylenetriamine (DETA) and silica coated MnFe2O4 nanoparticles (GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2) was prepared. The structure, thermal stability and magnetic properties of the composite were studied by FT-IR, XRD, SEM, EDS, VSM and TGA spectroscopic methods. The prepared composite showed magnetic property with a saturation magnetization of 3.0 emu/g. The adsorption properties of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite for methylene blue (MB) in aqueous solution were studied using batch method. The effects of important parameters on the surface adsorption process of MB, including pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage and initial dye concentration were investigated. The adsorption isotherm was in accordance with Langmuir model showing surface homogeneity of the adsorbent. According to the Langmuir analysis, the maximum adsorption capacity (qm) of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite for MB was found to be 243.91 mg/g. The kinetic studies showed that the adsorption was pseudo first-order process. In addition, the thermodynamic studies indicated the adsorption was spontaneous and endothermic process.

Subject terms: Green chemistry, Inorganic chemistry

Introduction

In recent years, the growth of industries such as textile, leather, cosmetics and printing has increased pollution caused by dyes in water environments1. Organic dyes due to the toxic and carcinogenic are serious hazard to human, microorganisms and the ecosystem2. Therefore, it is urgent and important to detect and remove these toxic components from wastewater. Many methods such as adsorption3, electrochemical oxidation4, photocatalytic degradation5, ion exchange6 and nanofiltration membranes7 have been applied to remove dyes from wastewater. Among these methods, the adsorption process seems to be the ideal choice due to the low initial cost, easy design, suitable flexibility and high efficiency8. In recent years, many adsorbents such as zeolites9, activated carbon10, alumina11, silica gel12, bentonite clays13, etc. have been used for removal of toxic dyes from aqueous solutions.

One of the most important dyes used in the textile industry is methylene blue (MB), which is chemically called 3,7-bis(dimethylamino) phenazathionium chloride or tetra methylthionine chloride and is a lasting cationic dye14. MB is a dangerous, toxic and carcinogenic organic dye, whose release in water harms human health and the ecosystem15. Therefore, it is important to look for efficient methods and materials for removal of MB. A lot of different materials have been suggested as potential adsorbents for methylene blue, such as activated clay16, graphitic materials17, cauliflower leave18, garlic pee19, clay graphene oxide iron oxide20, layered double hydroxide polymer21, etc. However, the design and search for new adsorbents are still urgent to enhance the adsorption capacity and improve the separation rate for removal of MB from wastewater. Today, nanocomposites have a good potential to absorb MB due to their high surface area22,23. Nanocomposites consisting of two parts, organic and inorganic can play an effective role in improving adsorption24.

In this field, Graphene based nanocomposites have also been investigated for the removal of some organic dyes and MB from wastewater25. Graphene oxide (GO) has a special structure of a two-dimensional honeycomb lattice with a single layer of sp2 carbon atoms26,27. Studies show that GO is an effective adsorbent towards dyes and heavy metal ions28–31. Its electronic and characteristic structure supply the electrostatic force and π–π stacking effect, which facilitate and contribute to the adsorption process32–35. Furthermore, GO is composed of many functional groups such as carboxyl groups, hydroxyl and epoxide, which lead to a hydrophilic and negatively charged surface. GO can be simply functionalized applying different treatments to change the functional groups for the purpose of gaining the desired surface properties. GO derivatives especially those functionalized with heteroatom have shown better performance as compared to its counter parts of graphene oxide36,37. In this filed, GO-calcium/alginate nanocomposite was synthesized and used to adsorb MB by Li et al., and the adsorption capacity was 163.93 mg g−1 38. Fan et al. synthesized a magnetic GO-chitosan nanocomposite and used it for removal of MB from aqueous solutions. The adsorption capacity was determined to be 95.31 mg g−1 39. In another study, Dai et al. doped the synthetic polymers such as PVA (poly (vinyl alcohol)) with graphene oxide in order to increase the ability of adsorption of MB. The adsorption capacity of GO/PVA composite for MB removal was 127.5 mg g−1 40.

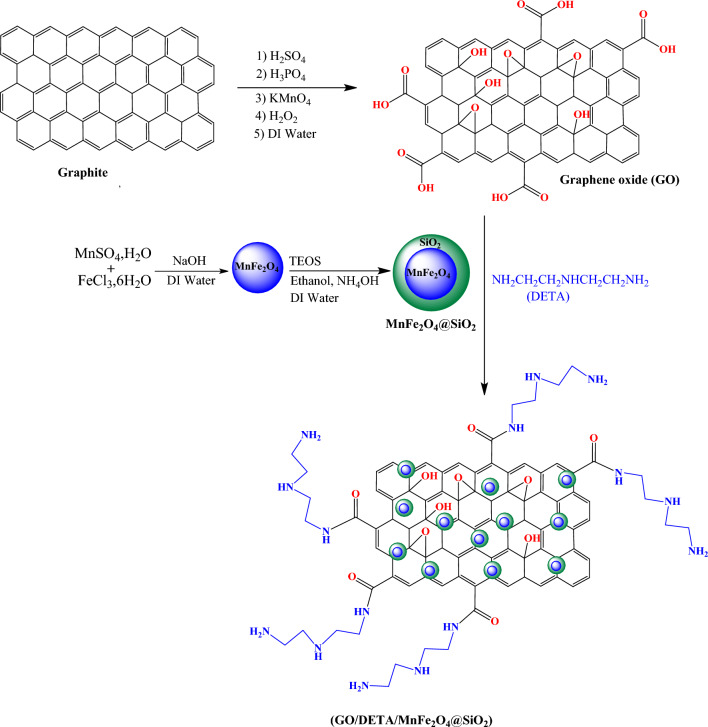

In this study, a new composite from GO, diethylenetriamine (DETA) and silica coated MnFe2O4 nanoparticles (GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2) was synthesized (Fig. 1). The composite prepared was applied for the removal of the MB from aqueous solution. Moreover, the effects of various parameters such as pH, adsorbent dosage, initial dye concentration and contact time on adsorption behavior were studied. Adsorption isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic studies have been reported to account for the nature of adsorption process.

Figure 1.

The synthesis route of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

Results and discussion

Characterization of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite

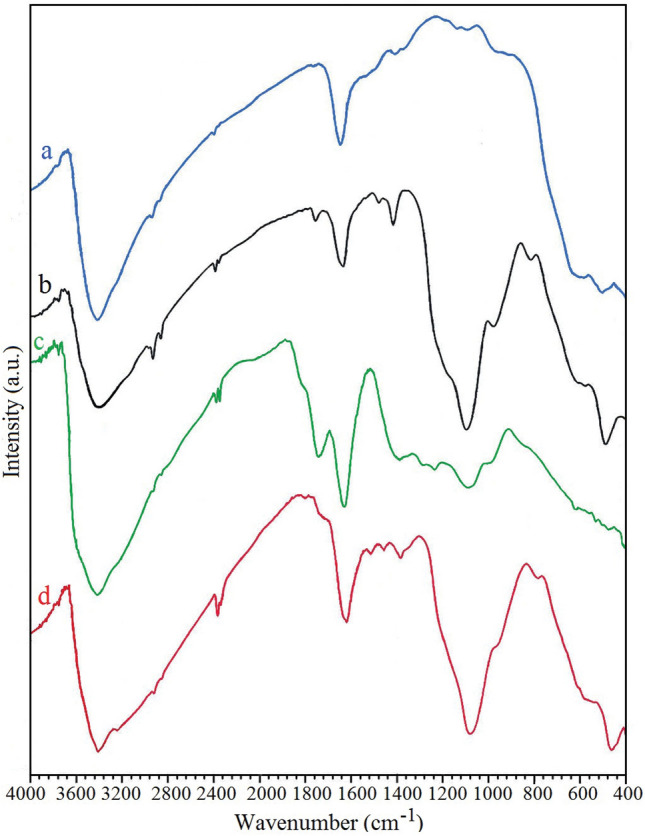

Infrared spectral characterization

The FT-IR spectra of synthesized compounds are demonstrated in Fig. 2. In MnFe2O4 FT-IR spectrum (Fig. 2a, blue line), a broad peak at 3428 cm−1 and a peak at 1627 cm−1 belong to stretching and bending vibration of hydroxyl (OH) groups, respectively41. Also, the peaks at 582 and 463 cm−1 are attributed to stretching vibration of Metal oxide (M–O) stretching vibrations of Mn–O and Fe–O, respectively42. The FT-IR spectrum of MnFe2O4@SiO2 nanoparticles is showed in Fig. 2b (black line). As it can be observed, MnFe2O4 nanoparticles after reaction with TEOS demonstrates a new peak at 1077 cm−1 which is assigned to stretching vibration of Si–O–Si. Figure 2c (green line) presents the FT-IR spectrum of GO. According to the GO FT-IR spectrum, a broad peak at 3600–2500 cm−1 belongs to stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups (OH) and adsorbed water molecules. Furthermore, the C=O stretching vibration of carboxylic acid group demonstrates a sharp peak at 1739 cm−1. Moreover, the peak at 1620 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration mode of C=C band and the peaks at 1228 and 1052 cm−1 are attributed to the C–O stretching of phenolic and epoxy groups43. The FT-IR spectrum of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is showed in Fig. 2d (red line). As it can be observed, after DETA and MnFe2O4@SiO2 modification, the peak of GO at 1739 cm−1 disappears indicating the reduction of C=O of carboxylic acid group because of amine functionalization. Also, new peaks appear at 1516 and 1085 cm−1 which belong to N–H bending and Si–O–Si stretching, respectively. Besides, in the FT-IR spectrum of GO the peak at 1381 cm−1 is attributed to C–OH band and due to ammination process its intensity has been decreased44.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of (a) MnFe2O4, (b) MnFe2O4@SiO2, (c) GO, (d) GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

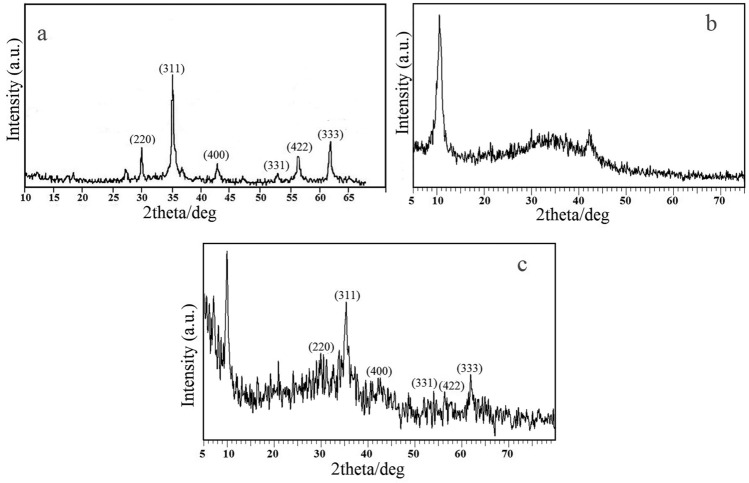

XRD analysis

X-ray diffraction of MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, GO and GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite are demonstrated in Fig. 3. For the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, XRD patterns (Fig. 3a) show the typical peaks 2θ = 30.20°, 35.45°, 43.25°, 53.50°, 57.15° and 63.40°, which are in agreement with the referenced data for MnFe2O4 nanoparticles45. Figure 3b presents XRD patterns of GO. The strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 10.49° shows that interlayer spacing of GO based on the Bragg equation is 8.4 Å. Figure 3c shows XRD patterns of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. The XRD pattern of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite includes the MnFe2O4 peaks with a peak at 2θ = 9.8° which is attributed to GO. The average particles size of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is calculated via Debye–Scherer equation:

where D is the average size, λ is the X-ray source wavelength (1.54 Å), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak and θ is the Bragg’s angle.

Figure 3.

XRD pattern of (a) MnFe2O4 nanoparticles, (b) GO and (c) GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

The average particle size of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is obtained based on Debye–Scherrer equation 149 nm.

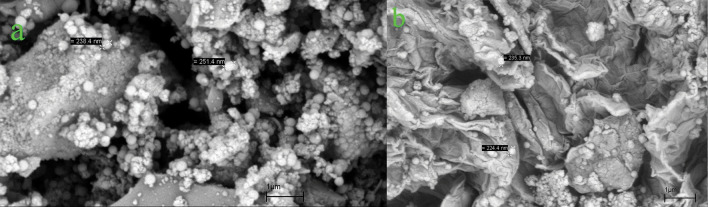

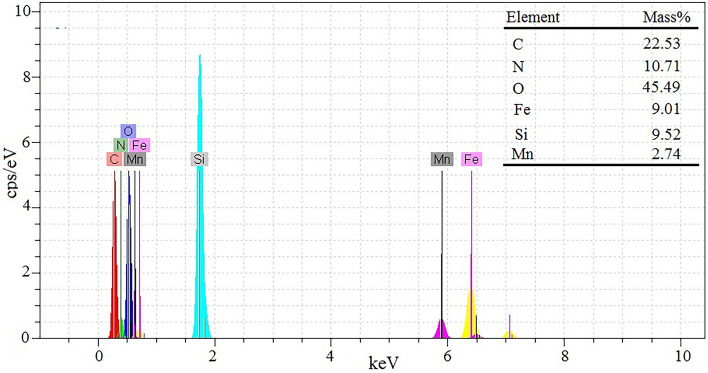

SEM and EDS analysis

The particle size and surface morphology of MnFe2O4@SiO2 and GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite were studied applying SEM technique. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, MnFe2O4@SiO2 nanoparticles are mostly in spherical shape and have average particle size about 244 nm. Figure 4b demonstrates the SEM image of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. SEM confirms verify the presence of spherical MnFe2O4@SiO2 nanoparticles on the surface of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 nanocomposite. The SEM image of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite obviously illustrates that it has created a layered structure and the spherical MnFe2O4@SiO2 nanoparticles have the average particle size about 230 nm. The chemical composition of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is studied via EDS analysis. The EDS spectrum of composite is presented in Fig. 5. EDS measurement confirms that the composite contains C, N, O, Si, Mn and Fe. The EDS spectrum of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite shows the atomic percentage of C, N, O, Si, Mn and Fe are 22.53, 10.71, 45.49, 9.01, 9.52 and 2.74, respectively.

Figure 4.

SEM images of (a) MnFe2O4@SiO2, (b) GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

Figure 5.

EDS patterns of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

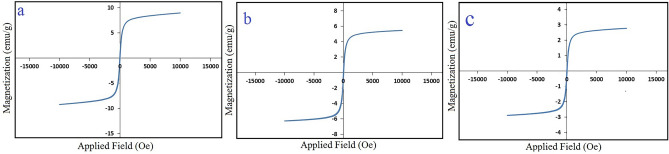

Magnetization analysis (VSM)

The magnetic moment of the MnFe2O4, MnFe2O4@SiO2 and GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite were calculated over a range of applied fields between 10,000 and − 10,000 Oe. Figure 6 shows magnetization curves of the MnFe2O4, MnFe2O4@SiO2 and GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 at room temperature. As presented, the saturation magnetization value of MnFe2O4 to GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 is decreased sequentially. These results confirm that, the surface of the MnFe2O4 nanoparticles are successfully coated with silica, DETA and GO. The saturation magnetization values of MnFe2O4, MnFe2O4@SiO2 and GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 are 10, 6 and 3 emu/g, respectively.

Figure 6.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of (a) MnFe2O4, (b) MnFe2O4@SiO2 and (c) GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

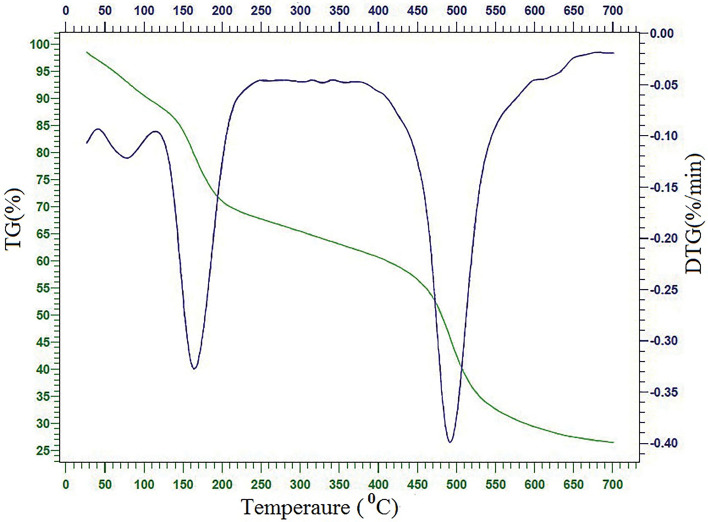

TGA analysis

Thermo-gravimetric Analysis (TGA) was done to predict the thermal stability of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. Figure 7 demonstrates the TGA-DTG curve of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. The TGA-DTG revealed three-stage degradation pattern between 25 and 600 °C. The first stage degradation happened between 25 and 135 °C with 11.5%, which could be assigned to the release of adsorbed water in the sample46. The second weight loss (18.4%) within 135–250 °C can be related to the degradation of groups that contain oxygen47. In the third stage, in the range from 250 to 550 °C, the major weight loss occurred and was decomposed 34.7% of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite, which can be at attributed to the decomposition of the carbon skeletons of GO and DETA48.

Figure 7.

TGA-DTG curve of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

Sorption studies of selected dye

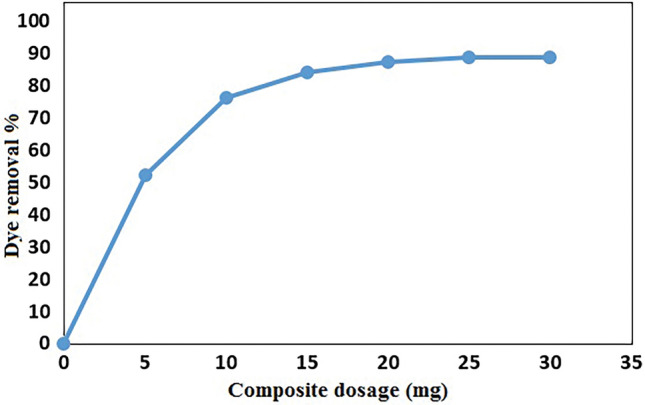

Effect of adsorbent dosage

The important factor that influences adsorption processes is adsorbent dosage since it characterizes the capacity of adsorbent for a given initial concentration of dye solution49. In our work, the effect of adsorbent dosage on adsorption removal of MB was investigated with sorbent amounts in the range 0–30 mg in the adsorption systems containing 40 mL of 100 mg/l solution of dye at 25 °C for 10 min. Figure 8 displays the effect of adsorbent dosage on the percentage removal of MB. As shown, the percentage removal of MB increased from 0 to 89% with increasing GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. This phenomenon can be related to the increasing of the surface area of the adsorbent and availability of more adsorption sites. Based on the results in Fig. 8, an optimum adsorbent dosage of 25 mg was selected.

Figure 8.

Effect of adsorbent dosage on removal of MB by GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (100 mg/l, 200 rpm, 25 °C, 10 min, pH = 7).

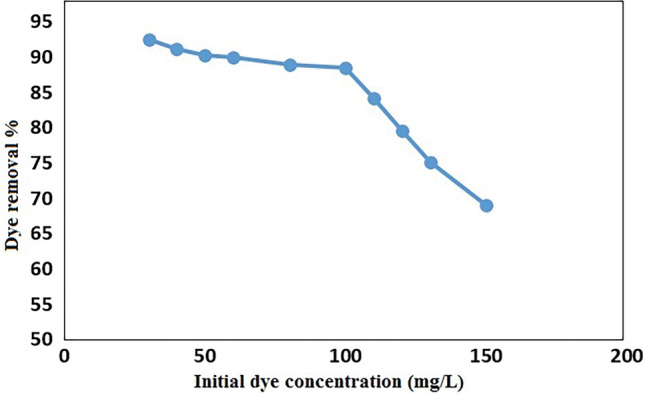

Effect of initial dye concentration

The influence of initial dye concentration on adsorption in case of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite was studied with different solution concentrations (30–150 mg/l) applying 25 mg of adsorbent. As it is shown in Fig. 9, the dye removal percentage is decreased with the increase of the initial dye concentration, which may be due to the decrease of enough number of active sites of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite for binding on the dye molecules.

Figure 9.

Effect of initial dye concentration on removal of MB by GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (25 mg, 200 rpm, 25 °C, 10 min, pH = 7).

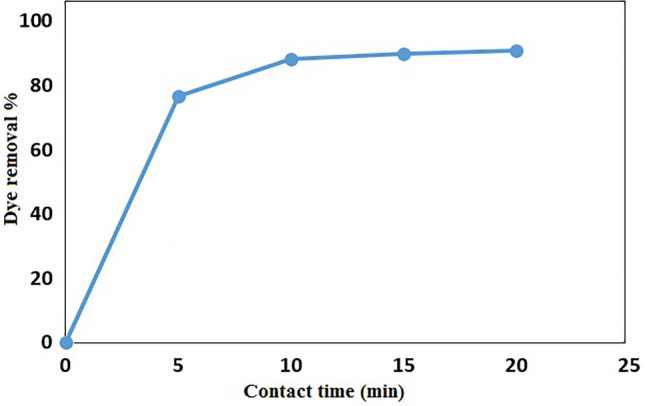

Effect of contact time

The effect of contact time on the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is demonstrated in Fig. 10. As can be seen in Fig. 10, with increasing contact time, the adsorption percentage of MB has increased rapidly in the early stages because of high availability of vacant adsorption sites. After a period of 10 min, the adsorption illustrated a steady increase.

Figure 10.

Effect of contact time on removal of MB by GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (100 mg/l, 25 mg, 200 rpm, 25 °C, pH = 7).

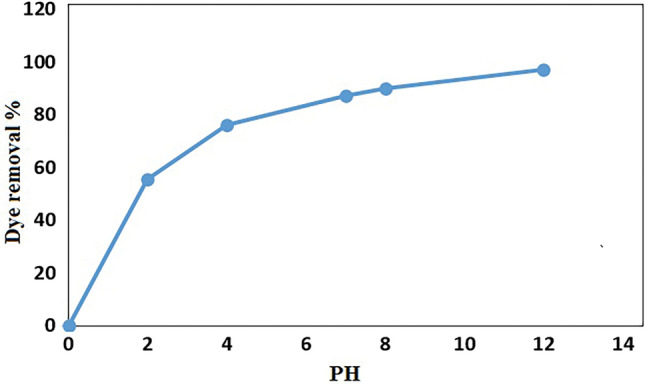

Effect of initial pH solution

The pH of solution is an important factor due to separation of different functional groups on the adsorbent and ionization of adsorbent in solution. The effect of pH on the sorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite was investigated within pH range 2–12 (Fig. 11). As it can be observed in Fig. 11 with increasing the pH solution, the removal of MB was increased. At higher pH, the surface has a negative charge and produces electrostatic interactions with MB cationic molecules50.

Figure 11.

Effect of pH solution on removal of MB by GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (200 rpm, 25 °C, 10 min).

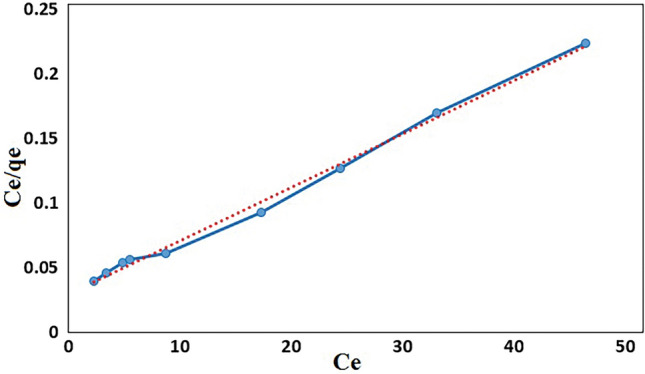

Adsorption isotherms

One of the important parameters for study of the interaction between adsorbent and dye are adsorption isotherms51. In this study, Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were applied to gain the isotherm parameters for adsorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. One of the well-known models to study the monolayer adsorption is Langmuir isotherm model. In this model the surface contains finite number of sites having equal activation energy of adsorption. The linear model of Langmuir isotherm is showed as follows:

| 1 |

where Ce is the concentration of the dye solution at equilibrium (mg/l), qe is the maximum amount of dye adsorbed (mg/g), qm indicates the value of monolayer adsorption capacity and KL is the constant value of Langmuir (mg/l). The values of KL and qm were obtained from the plot of (Ce/qe) versus Ce. The Langmuir plot for the adsorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is illustrated in Fig. 12.

Figure 12.

Langmuir plot for the adsorption of MB (200 rpm, 25 °C and pH = 7).

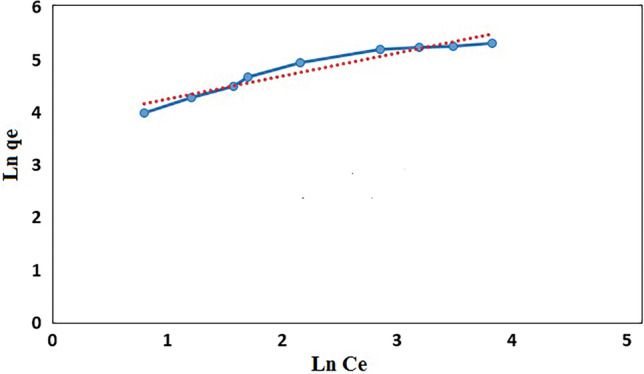

Freundlich isotherm model is used for reversible heterogeneous surface and is showed by the following linearized equation:

| 2 |

where KF and n are adsorption capacity (L/mg) and intensity of adsorption, respectively. The KF and 1/n can be calculated from the linear plot of Ln qe versus Ln Ce (Fig. 13). The 1/n values represent irreversible (1/n = 0), favorable (0 < 1/n < 1) or unfavorable (1/n > 1) condition for adsorption.

Figure 13.

Freundlich plot for the adsorption of MB (200 rpm, 25 °C and pH = 7).

The separation factor (RL) was determined by the following equation:

| 3 |

where KL is the Langmuir constant and C0 is the highest initial concentration of adsorbent (mg/l). The values of RL can demonstrate the shape of the isotherm. If RL > 1, the adsorption is unfavorable; if RL = 1, the adsorption is linear; if 0 < RL < 1, the adsorption is favorable and if RL = 0 the adsorption is irreversible. Table 1 shows the values of Langmuir and Freundlich parameters and the regression coefficients (R2) of the MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. Based on R2 values, the experimental data were found to fit with Langmuir isotherm model for adsorbent. Also, the value of RL lying in the range 0 < RL < 1 confirms the favorable condition for adsorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. Based on the result, the Langmuir model suggests homogeneous surfaces of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite and monolayer coverage of MB onto the adsorbent. The maximum monolayer adsorption capacity (qm) was 243.91 mg/g for MB.

Table 1.

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms parameters and correlation coefficients for the adsorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

| Langmuir isotherm parameters | Freundlich isotherm parameters | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qm (mg/g) | KL (L/mg) | RL | R2 | KF (L/mg) | n | R2 |

| 243.91 | 0.136 | 0.068 | 0.9951 | 44.45 | 2.29 | 0.9269 |

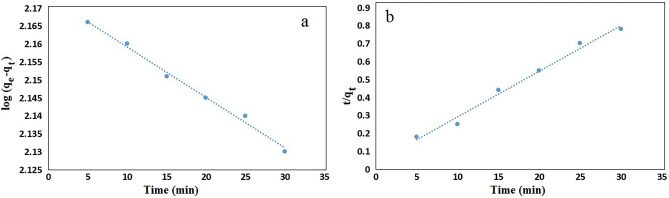

Kinetic model for MB adsorption

For investigating the mechanism of adsorption of MB two kinetic models: (i) pseudo-first order and (ii) pseudo-second order models have been studied. The linear form of pseudo-first-order52 and pseudo-second-order53 kinetic are expressed in Eqs. (4) and (5), respectively:

| 4 |

| 5 |

where qe and qt (mg/g) is the amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium and at time t, K1 and K2 (min−1) are the rate constants. The adsorption kinetics plots obtained for MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite are demonstrated in Fig. 14. The constants obtained for pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order models are listed in Table 2. Based on the results, the pseudo-first order model fit demonstrates a higher R2 value compared to the pseudo-second order for adsorbent. Also, the qe value gained by calculating pseudo-first order kinetic is closer to the experimental value (177.25 mg/g).

Figure 14.

Pseudo-first-order (a) and Pseudo-Second-order (b) model for the removal kinetics of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (100 mg/l, 25 °C and pH = 7).

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for the adsorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

| Pseudo-first-order | Pseudo-Second-order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe (mg/g) | K1 (× 10–3)(min−1) | R2 | qe (mg/g) | K2 (× 10–3)(min−1) | R2 |

| 147.91 | 3.22 | 0.9922 | 39.21 | 17.43 | 0.9876 |

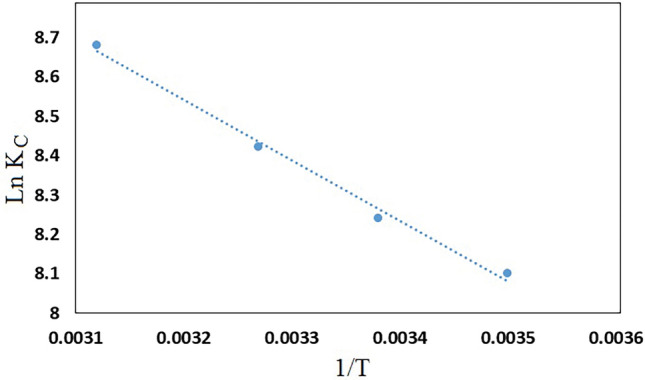

Thermodynamics of adsorption

In order to study the thermodynamic factors such as standard enthalpy change (ΔH°), standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) and standard entropy change (ΔS°), adsorption studies have been done at different temperatures (285–320 K). The thermodynamic factors were examined using following equations:

| 6 |

| 7 |

where KC is the thermodynamic equilibrium constant, T is the solution temperature and R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol K). The values of and were determined from slope and intercept of plot Ln KL vs 1/T (Fig. 15). Table 3 demonstrates the values of various thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. The positive value of indicates that the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is endothermic and the positive value of suggests the increase in randomness and disorder at the adsorbent-solution interface during the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite. Also, the negative values of show that the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is spontaneous process.

Figure 15.

Thermodynamic plot for removal of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite (200 rpm, 25 °C and pH = 7).

Table 3.

Thermodynamic parameters for the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

| Adsorbent | Adsorbate | ΔH° (kJ/mol) | ΔS° (kJ/mol) | ΔG° (kJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 285 K | 295 K | 305 K | 320 K | ||||

| GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 | MB | 12.53 | 0.12 | − 21.67 | − 22.87 | − 24.07 | − 25.87 |

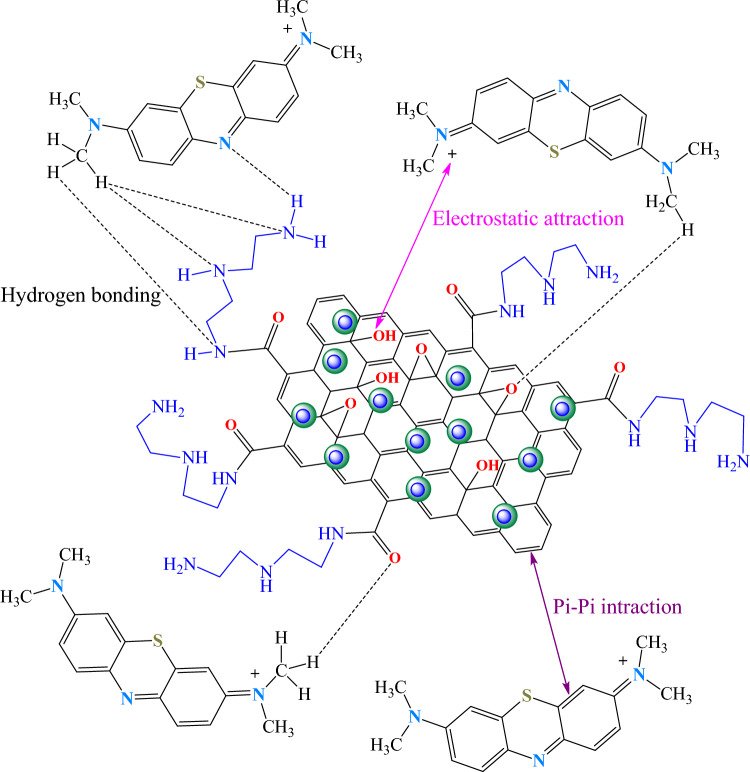

Adsorption mechanism

The pH of solution plays an important role because of the separation of different functional groups on the adsorbent and ionization of adsorbent in solution. It was found that the adsorption efficiency increased with increasing pH (Fig. 11). With the increase of pH, the negative charges in the solution are increased. This could be because of the ionization of functional groups such as hydroxyl on the composite. Therefore, increasing the surface charge density raises the MB removal percentage due to the increasing electrostatic interactions between the negative charge of the composite and the positive charge of the MB (Fig. 16)54. As a result, the electrostatic interactions between the positive charge on nitrogen group of MB and the negative charge on oxygen group may act as the critical adsorption mechanism55. Also, the localized π electrons in the conjugated aromatic rings of the composite can interact by the C–C double bond of MB through π-π interaction56. Finally, the hydrogen bonding interactions between amine or oxygen containing groups of composite and hydrogen containing groups of MB play important role in the adsorption of MB on GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite57 (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

Different adsorption mechanisms of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite for MB.

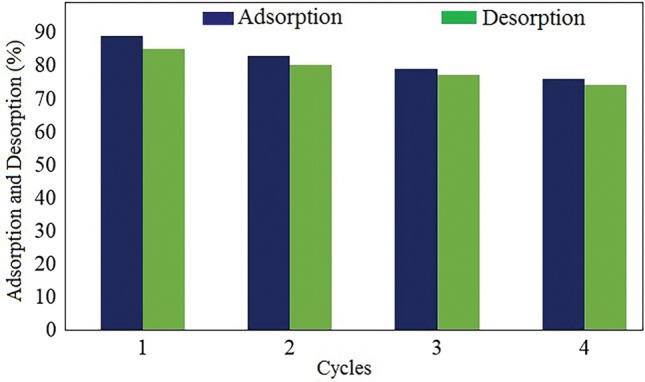

Reusability studies

In the study of adsorption process, reusability is of great importance from the cost point of view in water treatment. To study the regeneration ability of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite, four cycles of MB removal were evaluated58. The percentage removal of MB in 0.1 M HCl solution is represented in Fig. 17. As it can be observed from Fig. 17, the MB removal percentage decreased slightly and was still 74%.

Figure 17.

Regeneration studies for the adsorption–desorption of MB onto GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite.

Comparison with other reported adsorbents

The adsorption capacity of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite for removal of MB was compared with GO-based adsorbents and other adsorbents reported in the literature (Table 4). As it is shown in Table 4, the adsorption capacity of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite is acceptable for removal of MB from aqueous solutions.

Table 4.

Comparison of the adsorption capacity of present system with other reported systems.

| Adsorbents | Dye | qm (mg/g) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene oxide/calcium alginate | MB | 182 | 59 |

| Graphene–carbon nanotube | MB | 82 | 60 |

| RCE/GO | MB | 68 | 61 |

| Pt–Co@GO | MB | 90 | 62 |

| GO/silicates | MB | 90 | 63 |

| GO-PDA-PSPSH | MB | 185 | 64 |

| GO | MB | 100 | 65 |

| Poly(AA-co-AMPS)/montmorillonite | MB | 192 | 66 |

| MgAl-layered double hydroxides | MB | 102 | 67 |

| Poly(AAc) | MB | 220 | 68 |

| Cu-Z-GO-M | MB | 94.48 | 69 |

| GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 | MB | 243.91 | Present study |

Conclusion

The GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite has been successfully prepared and characterized by FTIR, XRD, SEM, EDS, VSM and TGA techniques. The composite showed magnetic property with a saturation magnetization of 3 emu/g. It was found that the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite was effective in adsorption of MB from aqueous solution. The effects of different parameters such as adsorbent dosage, initial drug concentration, pH and contact time were investigated. The Langmuir isotherm model was the best model to understand the adsorption process. According to the Langmuir analysis, the maximum adsorption capacity (qm) of the adsorbent for MB was obtained to be 243.91 mg/g. Kinetic studies demonstrated that the adsorption process followed pseudo-first order model for MB. The thermodynamic study illustrated that adsorption of MB on composite was spontaneous and endothermic, which was proceeded via hydrogen bonding, electrostatic and π-π interactions.

Experimental

Chemicals and instrumentation

All the chemicals were purchased from Merck. Methylene blue (chemical formula = C16H18ClN3S, Molecular weight (g/mol) = 319.85) was purchased from the Textile Factory. FT-IR spectra (Shimadzu prestige-21) were used to determine the identity of the as prepared nanocomposite. X-ray powder diffraction measurements were performed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD) (Perkin Elmer) at ambient temperature. The surface morphology of the synthesized compounds was identified with a scanning electron microscope (LECO SEM, Michigan, USA). The elemental analysis was performed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) on a scanning electron microscope, Mira 3-XMU model. Magnetic measurements were performed by means of the vibrating sample magnetometery method, using a VSM 7407 magnetometer, at room temperature. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a Perkin Elmer thermogravimetric analyzer. UV–visible spectra in the 200–1000 nm range were obtained in DMF solvent on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 45 spectrophotometer. A Jenway model 4510 pH-meter was used for pH measurements by use of a combined electrode. An ultrasonication probe (Karl Deutsch, Germany) was used to disperse the nanoparticles in the solution.

Preparation of the GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite

Preparation of GO

GO was prepared using the reported modified method70. Graphite powder (2.0 g) were dissolved in a mixture of H2SO4 and H3PO4 (150:15) with stirring at 60 °C. Then, 10 g of KMnO4 was added to the mixture and stirred for 12 h until its color changed to brown. Afterward, the mixture was cooled then 300 ml deionized water and 4 ml H2O2 (30%) was added. The mixture was centrifuged and the residue was washed with HCl (10%) followed by deionized water several times until the pH achieved neutral and dried under vacuum.

Preparation of Manganese Ferrite Nanoparticles (MnFe2O4)

MnFe2O4 NPs was prepared using the reported modified method71. Briefly, 0.9 g of FeCl3.6H2O and 1.5 g of MnSO4·H2O were dissolved in 200 ml deionized water with stirring at 80 °C. Then, NaOH (8 M) was added slowly to the solution to raise the pH to 10. The solution was stirred under nitrogen gas at 80 °C for 3 h. Afterward, MnFe2O4 NPs precipitates was separated by a magnetic separation and then washed with deionized water and ethanol. Then, the MnFe2O4 NPs were dried at 60 °C for 24 h.

Preparation of silica-coated nanoparticles MnFe2O4@SiO2

MnFe2O4 (6 g) was dispersed in a 100 ml of 0.1 M HCl aqueous solution. Then, solution ultrasonically agitated for 20 min. The nanoparticles isolated and washed with deionized water. Then, the nanoparticles were suspended 40 ml deionized water, 100 ml ethanol and 15 ml 28% ammonia solution and stirred for 1 h. Afterward, tetraethylorthosilicate (20 ml) in 20 ml ethanol was added to solution. This solution was stirred for 10 h at room temperature. Then, the product MnFe2O4@SiO2 were separated by an external magnet and washed with deionized water and ethanol.

Preparation of GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite

0.5 g of GO was placed into 100 ml DMF and ultrasonically dispersed for 1 h. Subsequently, 0.5 g MnFe2O4@SiO2 and 70 ml Diethylenetriamine (DETA) were added into to flask. The mixture refluxed with stirring for 24 h. the composite was isolated and washed with ethanol and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C.

Adsorption experiments

GO/DETA/MnFe2O4@SiO2 composite was used for removal of MB dye from aqueous solutions. For this aim, different factors such as adsorbent dose, contact time, initial concentration and PH on adsorption were investigated. For doing the experiments, solution of 100 mg/l of MB was prepared in deionized water. To prepare the experimental solutions, different amounts of composite (5–25 mg) were placed in a series of 40 ml of dye solution with different concentrations (40–120 mg/l) in 50 ml glass flasks. To study the effect of contact time of adsorbent on MB, prepared suspension solutions were stirred for 10–20 min. Beside, by using solutions of 0.01 N HCl or NaOH the effect of pH on the amount of adsorption was studied. The concentration of the MB was calculated by UV-spectrophotometer at λmax = 600 nm. Equations (8) and (9) were used to calculate the amount of dye adsorbed on the adsorbent (qe in mg/g) and the percentage of solution dye removal (R in %):

| 8 |

| 9 |

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentration of dye in solution (mg/l), respectively. V is the initial volume of the dye solution (l) and M is the mass of adsorbent used (g).

Author contributions

All authors have participated in the process of this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dutta S, Gupta B, Kumar Srivastava S, Kumar Gupta A. Recent advances on the removal of dyes from wastewater using various adsorbents: A critical review. Mater. Adv. 2021;2:4497–4531. doi: 10.1039/D1MA00354B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lellis B, Fávaro-Polonio CZ, Pamphile JA, Polonio JC. Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov. 2019;3:275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.biori.2019.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saadat A, Banaei A, Sattarifar M, Pargolghasemi P. Preparation 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehydecross-linked Fe3O4@chitosan-polyacrylamide nanocomposite for removal of everzol black from aqueous solutions. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:10618. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-37243-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu N, Wu Y. Removal of methylene blue by electrocoagulation: A study of the effect of operational parameters and mechanism. Ionics. 2019;25:3953–3960. doi: 10.1007/s11581-019-02915-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saufi H, Alouani M, Alehyen S, Achouri M, Aride J, Taibi M. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue from aqueous medium onto perlite-based geopolymer. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2020;2020:9498349. doi: 10.1155/2020/9498349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Ouardi Y, Virolainen S, Massima Mouele ES, Laatikainen M, Repo E, Laatikainen K. The recent progress of ion exchange for the separation of rare earths from secondary resources. Hydrometallurgy. 2023;2018:106047. doi: 10.1016/j.hydromet.2023.106047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Chen X, Feng Sh, Wan Y, Luo J. Nanofiltration for decolorization: Membrane fabrication, applications and challenges. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020;59:19858–19875. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.0c04277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Liang YQ, Mao XM, Li H. Efficient removal of Cu(II) from an aqueous solution using a novel chitosan assisted EDTA-intercalated hydrotalcite-like compound composite: Preparation, characterization, and adsorption mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;438:135531. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2022.135531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C. Adsorption of dye from wastewater by zeolites synthesized from fly ash: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2009;17:513–521. doi: 10.1016/S1004-9541(08)60239-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrera-Gonzalez AM, Caldera-Villalobos M, Pelaez-Cid A. Adsorption of textile dyes using an activated carbon and crosslinked polyvinyl phosphonic acid composite. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;234:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee S. Adsorption characteristics of alumina nanoparticles for the removal of hazardous dye, Orange G from aqueous solutions. Arab. J. Chem. 2019;12:5339–5354. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed MN, Ram RN. Removal of basic dye from waste-water using silica as adsorbent. Environ. Pollut. 1992;77:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(92)90161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahir SS, Rauf N. Removal of a cationic dye from aqueous solutions by adsorption onto bentonite clay. Chemosphere. 2006;63:1842–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fito J, Abewaa M, Mengistu A, Angassa K, Demeke Ambaye A, Moyo W, Nkambule T. Adsorption of methylene blue from textile industrial wastewater using activated carbon developed from Rumex abyssinicus plant. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:5427. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Lin Q, Liu X, Yang L, Ding J, Dong F, Li Y, Irfan M, Zhang P. Fast photocatalytic degradation of dyes using low-power laser-fabricated Cu2O-Cu nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2018;8:20277–20286. doi: 10.1039/C8RA03117G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng C, Pan Y. Adsorption of a cationic dye (methylene blue) onto spent activated clay. J. Hazard Mater. 2007;144:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Travlou NA. Graphite oxide/chitosan composite for reactive dye removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;217:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ansari SA, Khan F, Ahmad A. Cauliflower leave, an agricultural waste biomass adsorbent, and its application for the removal of MB dye from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2016;2016:8252354. doi: 10.1155/2016/8252354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hameed BH, Ahmad AA. Batch adsorption of methylene blue from aqueous solution by garlic peel, an agricultural waste biomass. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;164:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farooq N, Imran M, Shanableh A, Mahmood A, Jabeen S, Rehman A. Synthesis and characterization of clay graphene oxide iron oxide (clay/GO/Fe2O3) -nanocomposite for adsorptive removal of methylene blue dye from wastewater. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022;145:109956. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghanbari N, Ghafuri H. Design and preparation the novel polymeric layered double hydroxide nanocomposite (LDH / Polymer) as an efficient and recyclable adsorbent for the removal of methylene blue dye from water. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022;26:102377. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2022.102377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng T, Chen C, Ye C, Xie W, Zhang Z, Yuan T. Synthesis of KBiO3/Nano-Ag3PO4 composite photocatalyst and its application for degradation of organic pollutants under visible light. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2022;41:1942–1960. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang H, Hu X. Preparation of magnetic cellulose nanocrystal-modified diatomite for removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2022;41:787–798. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jawad AH, Saud Abdulhameed AS, Kashi E, Mundher Yaseen Z, Alothman ZA, Rizwan Khan M. Cross-Linked chitosan-glyoxal/kaolin clay composite: Parametric optimization for color removal and COD reduction of remazol brilliant blue R dye. J. Polym. Environ. 2021;30:164–178. doi: 10.1007/s10924-021-02188-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi YC, Wang AJ, Wu XL, Chen JR, Feng JJ. Green-assembly of three-dimensional porous graphene hydrogels for efficient removal of organic dyes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;484:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Z, Zeng Z, Chen A, Zeng G, Xiao R, Xu P, He K, Song Z, Hu L, Peng M. Differential behaviors of silver nanoparticles and silver ions towards cysteine: Bioremediation and toxicity to Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Chemosphere. 2018;203:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He K, Chen G, Zeng G, Chen A, Huang Z, Shi J, Huang T, Peng M, Hu L. Three-dimensional graphene supported catalysts for organic dyes degradation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018;228:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.01.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Y, Deng J, Zhu J, Zhou X, Bai R. Removal of mercury(ii) and methylene blue from a wastewater environment with magnetic graphene oxide: Adsorption kinetics, isotherms and mechanism. RSC Adv. 2016;6:82523–82536. doi: 10.1039/C6RA14651A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghasemabadi SM, Baghdadi M, Safari E, Ghazban F. Investigation of continuous adsorption of Pb (II), As (III), Cd (II), and Cr (VI) using a mixture of magnetic graphite oxide and sand as a medium in a fixed-bed column. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018;6:4840–4849. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2018.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sham AYW, Notley SM. Adsorption of organic dyes from aqueous solutions using surfactant exfoliated graphene. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018;6:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2017.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouhi M, Lakouraj MM, Tashakkorian H, Hasantabar V. Novel carbon based bioactive nanocomposites of aniline/indole copolymer for removal of cationic dyes from aqueous solution: Kinetics and isotherms. New J. Chem. 2019;43:2400–2410. doi: 10.1039/C8NJ02924E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z, He K, Song Z, Zeng G, Chen A, Yuan L, Li H, Hu L, Guo Z, Chen G. Antioxidative response of Phanerochaete chrysosporium against silver nanoparticle-induced toxicity and its potential mechanism. Chemosphere. 2018;211:573–583. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perreault F, Fonseca de Faria A, Elimelech M. Environmental applications of graphene-based nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:5861. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00021A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ersan G, Kaya Y, ApulO G, Karanfil T. Adsorption of organic contaminants by graphene nanosheets, carbon nanotubes and granular activated carbons under natural organic matter preloading conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;565:811. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ersan G, Apul OG, Perreault F, Karanfil T. Adsorption of organic contaminants by graphene nanosheets: A review. Water Res. 2017;126:385. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiruppathi AR, Sidhureddy B, Keeler W, Chen A. Facile one-pot synthesis of fluorinated graphene oxide for electrochemical sensing of heavy metal ions. Electrochem. Commun. 2017;76:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2017.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidhureddy B, Thiruppathi AR, Chen A. Synthesis and electrochemical study of graphene based nanomaterials for energy and environmental applications. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:7828–7831. doi: 10.1039/C7CC03060F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Du Q, Liu T, Peng X, Wang J, Sun J, Wang Y, Wu S, Wang Z, Xia Y. Comparative study of methylene blue dye adsorption onto activated carbon, graphene oxide, and carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2013;91:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2012.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan L, Luo C, Li X, Lu F, Qiu H, Sun M. Fabrication of novel magnetic chitosan grafted with graphene oxide to enhance adsorption properties for methyl blue. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012;215:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai J, Huang T, Tian S, Xiao Y, Yang J, Zhang N, Wang Y, Zhou Z. High structure stability and outstanding adsorption performance of graphene oxide aerogel supported by polyvinyl alcohol for waste water treatment. Mater. Des. 2016;107:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2016.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rashid Z, Naeimi H, Zarnani AH, Zarnani AH. Fast and highly efficient purification of 6× histidine-tagged recombinant proteins by Ni-decorated MnFe2O4@SiO2@NH2@2AB as novel and efficient affinity adsorbent magnetic nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016;6:36840–36848. doi: 10.1039/C5RA25949E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinatloo-Ajabshir S, Ghasemian N, Salavati-Niasari M. Green synthesis of Ln2Zr2O7 (Ln = Nd, Pr) ceramic nanostructures using extract of green tea via a facile route and their efficient application on propane-selective catalytic reduction of NOx process. Ceram. Int. 2020;46:66. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.08.231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeyaseelan A, Ghfar A, Naushad M, Viswanathan N. Design and synthesis of amine functionalized graphene oxide for enhanced fluoride removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:105384. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.105384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seredych M, Bandosz TJ. Mechanism of ammonia retention on graphite oxides: Role of surface chemistry and structure. J. Phys Chem C. 2007;111:15596–15604. doi: 10.1021/jp0735785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao Y, Zai J, Tao L, Li B, Han Q, Yu C, Qian X. MnFe2O4–graphene nanocomposites with enhanced performances as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:3939–3945. doi: 10.1039/c3cp50220a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanhaei B, Ayati A, Lahtinen M, Sillanpaa M. Preparation and characterization of a novel chitosan/Al2O3/magnetite nanoparticles composite adsorbent for kinetic, thermodynamic and isotherm studies of Methyl Orange adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;259:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2014.07.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Travlou NA, Kyzas GZ, Lazaridis NK, Deliyanni EA. Functionalization of graphite oxide with magnetic chitosan for the preparation of a nanocomposite dye adsorbent. Langmuir. 2013;29:1657–1668. doi: 10.1021/la304696y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun H, Cao L, Lu L. Magnetite/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: One step solvothermal synthesis and use as a novel platform for removal of dye pollutants. Nano Res. 2011;4:550–562. doi: 10.1007/s12274-011-0111-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fontana KB, Chaves ES, Sanchez JDS, Watanabe ERLR, Pietrobelli JMTA, Lenzi GG. Textile dye removal from aqueous solutions by malt bagasse: Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016;124:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao G, Li J, Ren X, Chen C, Wang X. Few-layered graphene oxide nanosheets as superior sorbents for heavy metal ion pollution management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:10454–10462. doi: 10.1021/es203439v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wawrzkiewicz M, Wiśniewska M, Gun'ko VM, Zarko VI. Adsorptive removal of acid, reactive and direct dyes from aqueous solutions and wastewater using mixed silica–alumina oxide. Powder Technol. 2015;278:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2015.03.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toor M, Jin B. Adsorption characteristics, isotherm, kinetics, and diffusion of modified natural bentonite for removing diazo dye. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;187:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.01.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Behnamfard A, Salarirad MM. Equilibrium and kinetic studies on free cyanide adsorption from aqueous solution by activated carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;170:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.04.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aboelfetoh EF, Gemeay AH, El-Sharkawy RG. Effective disposal of methylene blue using green immobilized silver nanoparticles on graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide sheets through one-pot synthesis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020;192:355. doi: 10.1007/s10661-020-08278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eltaweil AS, Mamdouh IM, Abd El-Monaem EM, El-Subruiti GM. Highly efficient removal for methylene blue and Cu2+ onto UiO-66 metal–organic framework/carboxylated graphene oxide-incorporated sodium alginate beads. ACS Omega. 2021;6:23528–23541. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c03479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Minitha CR, Lalitha M, Jeyachandran YL, Senthilkumar L, Rajendra Kumar RT. Adsorption behaviour of reduced graphene oxide towards cationic and anionic dyes: Co-action of electrostatic and π – π interactions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017;194:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim H, Kang SO, Park S, Park HS. Adsorption isotherms and kinetics of cationic and anionic dyes on three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide macrostructure. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;21:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2014.05.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye S, Zeng G, Wu H, Zhang C, Dai J, Liang J, Yu J, Ren X, Yi H, Cheng M. Biological technologies for the remediation of co-contaminated soil. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017;37:1062–1076. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2017.1304357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li YH, Du QJ, Liu TH, Sun JK, Wang YH, Wu SL, Wang ZH, Xia Y, Xia LH. Methylene, blue adsorption on graphene oxide/calcium alginate composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;95:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ai LH, Jiang J. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution with self-assembled, cylindrical graphene-carbon nanotube hybrid. Chem. Eng. J. 2012;192:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2012.03.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren F, Li Z, Tan WZ, Liu XH, Sun ZF, Ren PG, Yan DX. Facile preparation of 3D regenerated cellulose/graphene oxide composite aerogel with high-efficiency adsorption towards methylene blue. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;532:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nas MS, Calimli MH, Burhan H, Yilmaz M, Mustafov SD, Sen F. Synthesis, characterization, kinetics and adsorption properties of Pt-Co@GO nano-adsorbent for methylene blue removal in the aquatic mediums using ultrasonic process systems. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;296:112100. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen P, Cao ZF, Wen X, Wang J, Yang F, Wang S, Zhong H. In situ nano-silicate functionalized graphene oxide composites to improve MB removal. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017;81:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2017.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wan Q, Liu MY, Xie YL, Tian JW, Huang Q, Deng FJ, Mao LC, Zhang QS, Zhang XY, Wei Y. Facile and highly efficient fabrication of graphene oxide-based polymer nanocomposites through mussel-inspired chemistry and their environmental pollutant removal application. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52:504–518. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0349-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bu J, Yuan L, Jiang H, Wang C. Study on removal of methylene blue by condensation self-assembled graphene oxide/thiourea composite adsorbent. Sustainability. 2022;14:15290. doi: 10.3390/su142215290. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hosseinzadeh H, Khoshnood N. Removal of cationic dyes by poly(AA-co-AMPS)/ montmorillonite nanocomposite hydrogel. Desalin. Water Treatm. 2016;14:6372–6383. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2015.1008052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao J, Huang Q, Liu MY, Dai YF, Chen JY, Huang HY, Wen YQ, Zhu XL, Zhang XY, Wei Y. Synthesis of functionalized MgAl-layered double hydroxides via modified mussel inspired chemistry and their application in organic dye adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;505:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guin JP, Bhardwaj YK, Varshney L. Radiation crosslinked swellable ionic gels: Equilibrium and kinetic studies of basic dye adsorption. Desalin. Water Treatm. 2016;57:4090–4099. doi: 10.1080/19443994.2014.988656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang T, Yan M, He K, Huang Z, Zeng G, Chen A, Peng M, Li H, Yuan L, Chen G. Efficient removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions using magnetic graphene oxide modified zeolite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;543:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcano DC, Kosynkin DV, Berlin JM, Sinitskii A, Sun Z, Slesarev A, Tour JM. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4806–4814. doi: 10.1021/nn1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar S, Nair RR, Pillai PB, Gupta SN, Iyengar MAR, Sood AK. Graphene oxide–MnFe2O4 magnetic nanohybrids for efficient removal of lead and arsenic from water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:17426–17436. doi: 10.1021/am504826q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.