Abstract

Purpose of review

Cardiogenic shock is a clinical syndrome with different causes and a complex pathophysiology. Recent evidence from clinical trials evokes the urgent need for redefining clinical diagnostic criteria to be compliant with the definition of cardiogenic shock and current diagnostic methods.

Recent findings

Conflicting results from randomized clinical trials investigating mechanical circulatory support in patients with cardiogenic shock have elicited several extremely important questions. At minimum, it is questionable whether survivors of cardiac arrest should be included in trials focused on cardiogenic shock. Moreover, considering the wide availability of ultrasound and hemodynamic monitors capable of arterial pressure analysis, the current clinical diagnostic criteria based on the presence of hypotension and hypoperfusion have become insufficient. As such, new clinical criteria for the diagnosis of cardiogenic shock should include evidence of low cardiac output and appropriate ventricular filling pressure.

Summary

Clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock should be revised to better define cardiac pump failure as a primary cause of hemodynamic compromise.

Keywords: cardiac output, cardiogenic shock, clinical criteria, definition

INTRODUCTION

Cardiogenic shock is a clinical syndrome with widely varying definitions; nevertheless, all are based on the presence of cardiac pump failure resulting in inadequately low cardiac output and subsequent tissue hypoperfusion [1–5]. If we proceed from this definition, clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock should include evidence of cardiac pump failure with low cardiac output leading to tissue hypoperfusion. However, especially in the case of cardiogenic shock caused by acute myocardial infarction, clinical diagnostic criteria have been significantly simplified, largely comprising only the presence of hypotension and hypoperfusion, assuming that hypotension in acute myocardial infarction inherently implies cardiac pump failure and low cardiac output [1–4]. It is, therefore, widely accepted that in cases of acute myocardial infarction, detection of hypotension (or need for inotropes and/or vasopressors for maintenance of blood pressure) and any signs of hypoperfusion (including physical signs or laboratory findings) is sufficient for the clinical diagnosis of cardiogenic shock [1–4].

Recently, several published multicenter randomized clinical trials have focused on the efficacy of mechanical circulatory support in acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock [6–8,9▪▪,10▪,11▪▪]. Four of these trials examined veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and yielded neutral results [6–8,9▪▪]. One study demonstrated the beneficial effect of early initiation of Impella support [11▪▪]. The results can simply be interpreted that Impella does – and ECMO does not – work in cardiogenic shock. However, these conflicting results elicit serious questions whether the differences are entirely caused by the technologies used or could be, at least in part, explained by the study populations. The eligibility criteria differ significantly among individual trials. All five trials mandated the presence of hypoperfusion, two of five required low blood pressure [6,9▪▪], two required that low blood pressure should be accompanied by echocardiographic findings of structural disease [7,11▪▪] and, in one, persistent low blood pressure was required [8]. In only one trial, evidence of low cardiac output was an alternative criterion to low blood pressure [7]. Three of the five trials included comatose cardiac arrest survivors [6,8,9▪▪].

Because increasing experience and accumulating evidence with mechanical circulatory support have confirmed that these technologies can save lives in properly selected individuals, not only in cardiogenic shock, but also in refractory cardiac arrest, the issue of selecting the appropriate study population becomes extremely important.

Box 1.

no caption available

Is hypotension a surrogate for low cardiac output?

For decades, blood pressure has been a fundamental parameter that can easily be measured in all patients with suspected shock, and the presence of hypotension has indicated a high probability of shock [1,4,12]. When hypotension accompanies acute myocardial infarction, it can be assumed that infarction-associated systolic dysfunction is the cause of shock [13,14]. However, this is not necessarily true, and other factors may be responsible for – or, at least participate in – the drop in blood pressure [15]. It is fully understandable that hypotension was used in the past as a surrogate marker for low cardiac output as being immediately available and rapid measurement of cardiac output was not possible. However, the situation has changed. Currently, with the wide availability of ultrasound, assessment of cardiac output became an integral part of the initial examination in all patients with suspected cardiogenic shock, together with other ultrasound measurements useful for differential diagnosis of shock [14,16–18]. Moreover, other rapid and minimally invasive methods, such as arterial pressure analysis, could be used for hemodynamic assessment. Because both early ultrasound examination and invasive arterial pressure monitoring are guideline-recommended procedures in all patients with shock [1,4], cardiac output should be measured and should be used as primary hemodynamic parameter for the clinical diagnosis of cardiogenic shock instead of hypotension or together with hypotension [15,17].

In this context, it must be noted that all mechanical circulatory support devices were designed to increase flow and to increase total circulatory output; they may or may not also increase blood pressure based on other factors. Therefore, low cardiac output conditions can define a situation in which the major benefit from mechanical circulatory support could be anticipated. The same may not apply to all situations with low blood pressure.

A call for up-to-date hemodynamic criteria for cardiogenic shock was reflected in recent guidelines from the Heart Failure Society of America, American College of Cardiology, and American Heart Association [4], who suggested hemodynamic criteria that include not only cardiac output but also other important parameters such as left ventricular filling pressure [4].

Hypovolemia should be excluded

Low cardiac output is not the only hemodynamic criterion characterizing and defining cardiogenic shock. Evidence of cardiac pump failure as a cause of shock conditions should be supported by confirmation of normal or elevated ventricular filling. Exclusion of hypovolemia or relative hypovolemia is crucial for differential diagnosis and to enable distinguishing cardiogenic from hypovolemic shock (e.g., hemorrhagic) and, frequently, also from shock conditions with a significant peripheral component (e.g., vasoplegic or septic shock) [12,19]. Unfortunately, clinical diagnostic and eligibility criteria for clinical trials investigating cardiogenic shock frequently do not include the exclusion of hypovolemia because, especially in shock with acute myocardial infarction, increased left ventricular filling pressure is assumed [1,4,14,20]. However, this assumption may not apply in patients with concomitant vasodilatation for various reasons or in cardiac arrest survivors.

Presently, simple rapid ultrasound protocols enable the identification of hypovolemia with very high accuracy, and chest ultrasound is a guideline-recommended early examination in all individuals with suspected shock [1,4,16,19]. Moreover, other methods could also be used: measurement of left-ventricular end-diastolic pressure during or after coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention or hemodynamic measurement using a pulmonary artery catheter that is often not immediately available but enables complex hemodynamic monitoring with adjustment of therapeutic interventions and possible prognostic impact [12,21–24]. Furthermore, high central venous pressure may help to exclude hypovolemia with high probability; in contrast, low central venous pressure does not prove hypovolemia in case of left heart failure [25–28].

Cardiogenic shock versus shock in cardiac arrest survivors

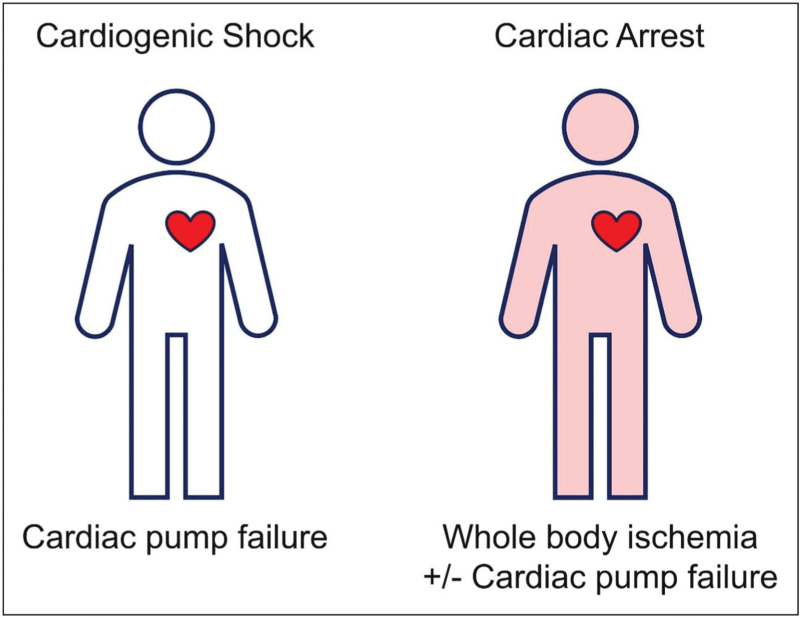

Although acute myocardial infarction or cardiac pump failure is a major cause of both cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest, the pathogenesis and hemodynamic characteristics of comatose patients after resuscitation significantly differ from those with “pure” cardiogenic shock. Whereas cardiogenic shock is entirely caused by cardiac pump failure, whole body ischemia during cardiac arrest may not only affect the brain and heart but also the peripheral tissues. This is the cause of a frequent and significant peripheral component of shock after prolonged cardiac arrest (Fig. 1), although low cardiac output is present in a substantial proportion of general cardiac arrest survivors [29–31].

FIGURE 1.

Causes of shock in “true” cardiogenic shock and shock after prolonged cardiac arrest.

Josiassen et al.[32] compared hemodynamic characteristics of patients with acute myocardial infarction related cardiogenic shock with and without cardiac arrest. The investigators used the presence of hypotension and hypoperfusion as inclusion criteria, similar to several recent randomized trials. Baseline mean cardiac output was 4.6 l/min in patients after cardiac arrest and 4.4 l/min in those without cardiac arrest (both within normal limits!). Lower heart rate was also observed in cardiac arrest survivors, indicating higher stroke volume in these patients, and the improvement of cardiac output was significantly faster in the cardiac arrest group. Mean baseline venous oxygen saturation (i.e., SvO2) was within normal range in both groups and significantly higher in cardiac arrest survivors, reaching 70% (i.e., values that almost preclude the presence of true cardiogenic shock and indicate presence of peripheral component of hypotension) [32]. Of note, whereas the major cause of death in those with cardiogenic shock is cardiac failure, patients after cardiac arrest mostly die from anoxic brain damage [32]. It is difficult to assume that any specific intervention for cardiogenic shock could revert established anoxic brain injury.

In fact, cardiac arrest survivors represent a substantial proportion of the study populations in recent randomized trials focusing on mechanical circulatory support interventions for cardiogenic shock: 42% in IABP-SHOCK 2 [33]; 95% in ECLS-SHOCK I [6]; 49% in EURO SHOCK [8]; and 78% in ECLS-SHOCK II [9▪▪]. It is reasonable to speculate that enrollment of comatose patients after resuscitation for cardiac arrest might significantly influence the neutral results of these trials. Furthermore, elevated serum lactate level was one of the accepted markers for the diagnosis of tissue hypoperfusion in these trials [9▪▪]. It is noteworthy that in cardiac arrest survivors, high lactate level is not a marker of the severity of cardiogenic shock and tissue hypoperfusion but the result of whole-body ischemia during cardiac arrest.

In this context, results of recent randomized trials investigating mechanical circulatory support in patients with acute myocardial infarction and hypotension must be interpreted with caution considering that the study populations were often not patients who experienced “true” cardiogenic shock. Noteworthy, numerically better outcomes with ECMO was observed in some of the trials in a subgroup without cardiac arrest [9▪▪] and microaxial pump Impella CP decreased mortality in the DanGer Shock trial, in which comatose cardiac arrest survivors were not enrolled [11▪▪].

Suggested clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock

Based on current evidence and advances in widely available rapid diagnostic methods, the historical clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock – hypotension and hypoperfusion – are not only insufficient, but also obsolete, and should be abandoned. Hypotension can no longer be considered as a surrogate marker of low cardiac output because cardiac output may – and should be – assessed directly. Similarly, normal or elevated filling pressures no longer have to be merely assumed but should be directly measured.

Fast and precise diagnosis of cardiogenic shock can be achieved using physical examination and measurement of blood pressure, diuresis, and basic laboratory parameters, but also ultrasound/echocardiography, analysis of invasive arterial pressure waveform and, in the case of cardiac catheterization, also direct measurement of left-ventricular end-diastolic pressure. With accumulating evidence supporting the benefit of pulmonary artery catheter monitoring in patients with cardiogenic shock [24], diagnosis can be confirmed using this hemodynamic measurement.

Using the above-mentioned methods, clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock should be based on evidence of the following: hypotension with low cardiac output; tissue hypoperfusion; and exclusion of hypovolemia or relative hypovolemia (i.e., exclusion of low ventricular filling pressure) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Suggested clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock and methods of confirmation

| Criterion | Methods of confirmation |

| 1. Low cardiac output | US, arterial pressure waveform analysis, PAC |

| 2. Tissue hypoperfusion | Physical examination, biochemical markers (SvO2, lactate), NIRS |

| 3. Exclusion of hypovolemia (absolute or relative) | US, arterial pressure waveform analysis, cardiac catheterization, PAC, CVP |

CVP, central venous pressure; NIRS, near infrared spectroscopy; PAC, pulmonary artery catheter; SvO2, venous oxygen saturation; US, ultrasound.

However, cardiogenic shock has always been considered to be a very complex hemodynamic deterioration caused by cardiac failure, which influences other tissues and may result in the failure of other organs [12,34]. Therefore, in the later phases of cardiogenic shock, peripheral failure develops, contributing to further hemodynamic deterioration and resulting in combined cardiogenic and distributive shock [14,34,35]. Despite the advances in current diagnostic modalities and strategies, diagnosis of cardiogenic shock and differential diagnosis of other and combined forms of shock will always remain challenging.

CONCLUSION

For many years, the clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock have included the presence of hypotension and hypoperfusion. These criteria have also been used for enrollment in clinical trials focused on interventions for cardiogenic shock, including mechanical circulatory support. However, accumulating evidence indicates that these criteria do not fully match with the definition of cardiogenic shock. Furthermore, rapid diagnostic modalities have been much improved during the past years. As such, clinical diagnostic criteria for cardiogenic shock should be updated and newly based on the evidence of low cardiac output. Due to different pathophysiological and hemodynamic characteristics, cardiac arrest survivors should not be enrolled in clinical trials focused on cardiogenic shock and will not if the new criteria are applied.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

The present review was supported by the Charles University Research Program “Cooperatio Cardiovascular Sciences”, by the grant from the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic – Conceptual Development of Research Organization, Motol University Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic, 00064203 and by the grant from the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic MH CZ–DRO-VFN00064165.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Ostadal has received speaker's honoraria from Abiomed, Edwards, Fresenius and Getinge. Dr Belohlavek has received speaker's honoraria from Abiomed, Getinge and Resuscitec.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021; 42:3599–3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry TD, Tomey MI, Tamis-Holland JE, et al. Invasive management of acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021; 143:e815–e829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naidu SS, Baran DA, Jentzer JC, et al. SCAI SHOCK Stage Classification Expert Consensus Update: A Review and Incorporation of Validation Studies: this statement was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), American Heart Association (AHA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care (ACVC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in December 2021. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 79:933–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022; 145:e895–e1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg DD, Bohula EA, Morrow DA. Epidemiology and causes of cardiogenic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care 2021; 27:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner S, Guenther SPW, Lackermair K, et al. Extracorporeal life support in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73:2355–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostadal P, Rokyta R, Karasek J, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the therapy of cardiogenic shock: results of the ECMO-CS randomized clinical trial. Circulation 2023; 147:454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banning AS, Sabate M, Orban M, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or standard care in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: the multicentre, randomised EURO SHOCK trial. EuroIntervention 2023; 19:482–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪▪.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Akin I, et al. Extracorporeal life support in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2023; 389:1286–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the largest randomized trial to date focused on the use of mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock.

- 10▪.Zeymer U, Freund A, Hochadel M, et al. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with infarct-related cardiogenic shock: an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2023; 02:1338–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the only individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized trials focused on the use of ECMO in patients with acute myocardial infarction related cardiogenic shock.

- 11▪▪.Moller JE, Engstrom T, Jensen LO, et al. Microaxial flow pump or standard care in infarct-related cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2024; 390:1382–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the only randomized trial to date that has demonstrated a mortality reduction with the use of mechanical circulatory support in cardiogenic shock.

- 12.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1726–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeymer U, Bueno H, Granger CB, et al. Acute Cardiovascular Care Association position statement for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: a document of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020; 9:183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chioncel O, Parissis J, Mebazaa A, et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and contemporary management of cardiogenic shock – a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2020; 22:1315–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostadal P, Belohlavek J. Response by Ostadal and Belohlavek to letter regarding article, “Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the therapy of cardiogenic shock: results of the ECMO-CS randomized clinical trial”. Circulation 2023; 148:804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2023; 44:3720–3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jentzer JC, Tabi M, Burstein B. Managing the first 120 min of cardiogenic shock: from resuscitation to diagnosis. Curr Opin Crit Care 2021; 27:416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jentzer JC, Wiley BM, Anavekar NS, et al. Noninvasive hemodynamic assessment of shock severity and mortality risk prediction in the cardiac intensive care unit. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021; 14:321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47:1181–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furer A, Wessler J, Burkhoff D. Hemodynamics of cardiogenic shock. Interv Cardiol Clin 2017; 6:359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent JL, Joosten A, Saugel B. Hemodynamic monitoring and support. Crit Care Med 2021; 49:1638–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flick M, Bergholz A, Sierzputowski P, et al. What is new in hemodynamic monitoring and management? J Clin Monit Comput 2022; 36:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinsky MR, Cecconi M, Chew MS, et al. Effective hemodynamic monitoring. Crit Care 2022; 26:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garan AR, Kanwar M, Thayer KL, et al. Complete hemodynamic profiling with pulmonary artery catheters in cardiogenic shock is associated with lower in-hospital mortality. JACC Heart Fail 2020; 8:903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monge Garcia MI, Santos Oviedo A. Why should we continue measuring central venous pressure? Med Intensiva 2017; 41:483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinsky MR, Kellum JA, Bellomo R. Central venous pressure is a stopping rule, not a target of fluid resuscitation. Crit Care Resusc 2014; 16:245–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magder S. Understanding central venous pressure: not a preload index? Curr Opin Crit Care 2015; 21:369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magder S. Right atrial pressure in the critically ill: how to measure, what is the value, what are the limitations? Chest 2017; 151:908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grand J, Kjaergaard J, Bro-Jeppesen J, et al. Cardiac output, heart rate and stroke volume during targeted temperature management after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: association with mortality and cause of death. Resuscitation 2019; 142:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grand J, Wiberg S, Kjaergaard J, et al. Increasing mean arterial pressure or cardiac output in comatose out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients undergoing targeted temperature management: effects on cerebral tissue oxygenation and systemic hemodynamics. Resuscitation 2021; 168:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grand J, Hassager C, Schmidt H, et al. Serial assessments of cardiac output and mixed venous oxygen saturation in comatose patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care 2023; 27:410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Josiassen J, Lerche Helgestad OK, Moller JE, et al. Hemodynamic and metabolic recovery in acute myocardial infarction-related cardiogenic shock is more rapid among patients presenting with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0244294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, et al. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1287–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertini P, Guarracino F. Pathophysiology of cardiogenic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care 2021; 27:409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Backer D, Creteur J, Dubois MJ, et al. Microvascular alterations in patients with acute severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock. Am Heart J 2004; 147:91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]