Abstract

Gene expression of nonsegmented negative-sense RNA viruses involves sequential synthesis of monocistronic mRNAs and transcriptional attenuation at gene borders resulting in a transcript gradient. To address the role of the heterogeneous rabies virus (RV) intergenic regions (IGRs) in transcription attenuation, we constructed bicistronic model RNAs in which two reporter genes are separated by the RV N/P gene border. Replacement of the 2-nucleotide (nt) N/P IGR with the 5-nt IGRs from the P/M or M/G border resulted in attenuation of downstream gene transcription to 78 or 81%, respectively. A severe attenuation to 11% was observed for the 24-nt G/L border. This indicated that attenuation in RV is correlated with the length of the IGR, and, in particular, severe downregulation of the L (polymerase) gene by the 24 nt IGR. By reverse genetics, we recovered viable RVs in which the strongly attenuating G/L gene border of wild-type (wt) RV (SAD L16) was replaced with N/P-derived gene borders (SAD T and SAD T2). In these viruses, transcription of L mRNA was enhanced by factors of 1.8 and 5.1, respectively, resulting in exaggerated general gene expression, faster growth, higher virus titers, and induction of cytopathic effects in cell culture. The major role of the IGR in attenuation was further confirmed by reintroduction of the wt 24-nt IGR into SAD T, resulting in a ninefold drop of L mRNA. The ability to modulate RV gene expression by altering transcriptional attenuation is an advantage in the study of virus protein functions and in the development of gene delivery vectors.

The major element of transcriptional regulation in nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses (Mononegavirales), which include the families Filoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, and Bornaviridae, is the gene order. The viral RNA polymerase is assumed to enter the genome at the 3′ end and to sequentially transcribe a leader RNA and up to 10 mostly monocistronic mRNAs (1, 2, 14). Due to dissociation of the polymerase at each gene border a progressive loss toward the template 5′ end is observed, resulting in a gradient of transcripts following the gene order (20). Invariably, the 5′-terminal gene of Mononegavirales is the polymerase gene (L; large), so that L mRNAs are the least abundant viral transcripts in infected cells (10, 29).

The gene borders of Mononegavirales are defined by conserved sequences. Colinear transcription of a gene proceeds to a short U stretch, which is reiteratively copied to form the mRNA's poly(A) tail. The polymerase then is thought to reinitiate transcription at a consensus start signal, which is usually located downstream of the polyadenylation signal. The nucleotides separating the two signals are apparently not transcribed and are known as the intergenic region IGR (3). Once recombinant systems allowing the experimental modification of cis-acting sequences became available (reviewed in reference 10), the functions of the conserved stop/polyadenylation and restart signals were rapidly verified (4, 24, 32). However, functions of IGRs are not well understood so far.

IGRs may be highly variable in sequence and length, suggesting regulatory functions in virus transcription. In the prototype rhabdovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), the five protein-encoding genes (3′-N-P-M-G-L-5′) are usually separated by a conserved IGR consisting of the dinucleotide GA (31). At each gene border of VSV, approximately one-third of the polymerases that terminated an upstream mRNA fail to initiate transcription of the downstream gene (20). In contrast, in the closely related rabies virus (RV) (Lyssavirus genus), the four IGRs comprise different numbers of nucleotides, namely, 2 (N/P), 5 (P/M), 5 (M/G), and 24 to 29 (G/L) (11, 39). This suggests differential attenuation, which would provide a more refined means for regulation of transcription. In particular, RV L seems to be severely downregulated, with L mRNA (and L protein) hardly detectable.

The apparent correlation of IGR length and attenuation prompted us to analyze whether transcription of recombinant RV could be modified by exchanging particular IGRs and how this would affect virus phenotype. In particular, one aim was to exaggerate RV gene expression. We first analyzed transcription from bicistronic reporter gene model genome analogs that contained either the authentic N/P gene junction or gene junctions that had been altered to contain the different intergenic sequences. Indeed, the 2-nucleotide (nt) N/P IGR was superior to others in supporting transcription of the downstream reporter gene, whereas a significantly reduced transcription was mediated by the 24-nt G/L IGR. A series of recombinant RV mutants could be generated by exchange of the 24-nt G/L IGR with the 2-nt IGR derived from the N/P gene border. Most interestingly, these mutants grew better than wild-type (wt) virus in cell culture and showed cytopathic phenotypes, raising the question of why L is downregulated in natural viruses. Viruses overexpressing L protein might be very well suited for vector purposes, especially when the addition of multiple genes into the virus genome is required and where low expression of L protein due to additional transcription attenuation by extra gene borders may be limiting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and cDNA rescue experiments.

Viruses were grown on BHK-21 clone BSR cell monolayers. Minigenome particles were recovered from pSDI-CL(NP) or its derivatives as described previously (13) by coexpression of minigenome cDNA and virus proteins N, P, M, G, and L in vaccinia virus vTF7-3-infected cells (17). Cell culture supernatants were harvested 3 days after transfection, partially cleared of vaccinia virus by centrifugation, and then transferred on fresh BSR cells. One hour after passage, cells were superinfected with recombinant helper virus SAD Ambi (15, 16), which allows selective amplification of minigenome RNA. Mutagenesis of pSDI-CL(NP) was performed as described previously (33) using primers igPM (5′-CATCATGAAAAAAACAGGCAACACCCCTCCTTTCG-3′), igMG (5′-CATCATGAAAAAAACTATTAACACCCCTCCTTTCG-3′) and igGL (5′-CATCATGAAAAAAACATTAGATCAGAAGAACAACTGGCAACACCCCTCCTTTCG-3′).

Recombinant viruses SAD T and SAD TigGL were recovered as described previously (34) after coexpression of the full-length antigenome sense RNA from plasmid-encoded cDNA and of plasmids encoding RV proteins N, P, and L (13) in BSR cells expressing T7 RNA polymerase from recombinant vTF7-3. SAD T2 was recovered in BSR T7/5 cells constitutively expressing T7 RNA polymerase (6, 16). For virus recovery, 10 μg of full-length cDNA and plasmids pTIT-N (5 μg), pTIT-P (2.5 μg), and pTIT-L (2.5 μg) were cotransfected in ∼106 BSR T7/5 cells grown in 8-cm2 culture dishes after CaPO4 precipitation (mammalian transfection kit; Stratagene). Three days posttransfection, fresh culture medium was added, and after another 3 days, cell culture supernatants were harvested and transferred on BSR cells. Two days after passage, infectious virus was detected by immunostaining against RV N protein (34).

Immunoblotting.

Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell) in a semidry transfer apparatus (OWL Scientific). After incubation with blocking solution (2.5% dry milk and 0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBST]) at room temperature for 1 h, membranes were incubated overnight with rabbit serum raised against purified RV ribonucleoprotein (S50; 1:20,000) in PBST. The blot was then incubated for 2 h with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Dianova) diluted 1:10,000 in PBST. Proteins were visualized by chemifluorescence (Renaissance; NEN).

Construction of RV full-length cDNA clones.

For modification of the SAD L16 G/L gene border, a 2.8-kb subclone of pSAD L16 spanning the 3′-terminal part of the G gene and 5′-terminal part of the L gene (pPsiX8ΔBEH; SAD L16 positions 3823 to 6668) was added (34). A 0.6-kb HindIII/NsiI fragment of pPsiX8ΔBEH containing the G/L gene border sequence was replaced with a HindIII/NsiI fragment of pT7T-L (13) after Klenow fragment fill-in resulting in deletion of the gene border sequence and generation of an NheI site at the former HindIII location (pPsiX8GL). The N/P gene border was inserted into the new NheI recognition site as a 121-bp XbaI/SpeI DNA fragment from pSKNP (16). A 2.4-kb StuI fragment from the resulting pPsiGNPL was exchanged with the corresponding fragment of the full-length cDNA clone pSAD L16, resulting in pSAD T. For construction of pSAD TigGL, the G/L gene border of pSAD T was excised with HpaI and NheI and was replaced with the HpaI/NheI fragment containing the modified N/P gene border of pSDI-CL(igGL).

SAD T2 was combined from several plasmids containing modified virus cDNA. The remainder of the L 5′-noncoding region was exchanged with that of the P gene by PCR using the primers 6410M (5′-AAGTTGACTAACTTGTCTTTT-3′), and S-Turbo-L (5′-GCCTTTCGAACCATCCCAAACATGCTCGATCCTGGAGAGGTC-3′). The latter contained an AsuII site (italics) upstream of the initiation codon (bold) for joining of the PCR product to the N/P gene border sequence present in a pBluescript vector (pSK9). The resultant plasmid, pPCR-L, containing the modified 5′-terminal part of the L gene was used to replace the original 5′-terminal part of the L gene of the full-length pSAD L16 as well as the entire upstream half of the genome cDNA spanning the N, P, M, and G genes (PstI in the upstream multiple cloning site and BsgI in the L coding region). The resulting plasmid, pSAD LPCR, (organization: T7 promoter-N/P gene border-L gene-trailer-hepatitis D virus ribozyme) was completed to a full-length cDNA (pSAD ST) by reinsertion of a fragment containing the 3′-terminal half of the genome and in which the P/M and M/G gene borders were exchanged with the N/P gene border (pSK-NPMG; see below). This procedure resulted also in the deletion of part of the G 3′-noncoding region (Ψ gene) in pSAD ST. For generation of pSAD TB and pSAD T2, a cDNA fragment from SAD L16 spanning the N, P, and M genes and part of the G gene and a cDNA fragment from SAD L16 spanning the N and P genes and part of the M gene, respectively, were used to replace the corresponding sequences of pSAD ST.

The intermediate plasmid pSK-NPMG, in which the P/M and the M/G gene borders are replaced by the N/P gene border, was assembled from three plasmids, namely, pSAD L16 (N and P genes), pSK9M, which contained an N/P border (109-bp MaeIII/BglII cDNA fragment of pSAD L16, positions 1412 to 1521) upstream of the M gene, and pSK9G, which contained the N/P border upstream of the G gene. Plasmids pSK9M and pSK9G were used to generate pSK9MG by insertion of a SalI/BglII fragment from pSK9G in pSK9M. A fragment from pSK9MG spanning the M and G genes was then ligated to a fragment from pSAD L16 comprising the RV N and P genes to give rise to pSK-NPMG. The final sequences of the full-length clones can be obtained from the authors by e-mail.

RNA analysis.

Total RNA from cells was isolated 2 days after infection with the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), and mRNA was enriched by using the Oligotex mRNA purification kit (Qiagen) according to the supplier's instructions. Agarose gel electrophoresis and Northern blotting were performed as described previously (11). cDNA fragments were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham) by nick translation (nick translation kit; Amersham). Hybridization signals were quantitated by phosphorimaging (Storm; Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

IGRs modulate transcription restart.

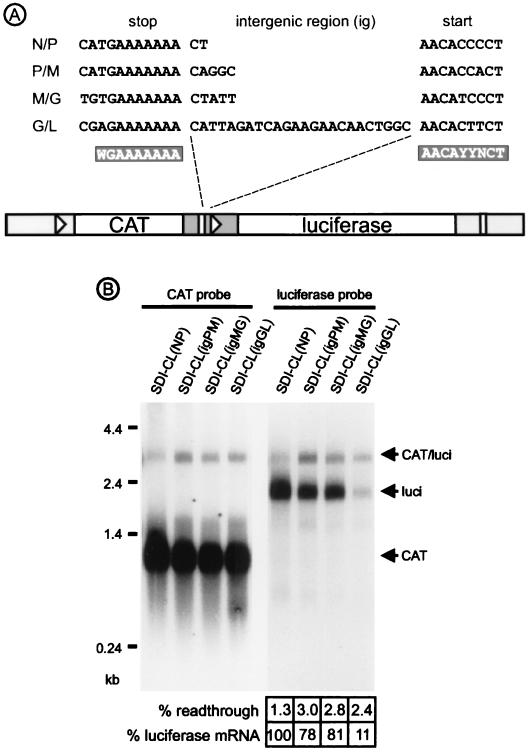

In contrast to the prototype rhabdovirus VSV, in which all IGRs usually consist of a conserved dinucleotide (31), the four IGRs separating RV genes contain 2, 5, 5, and 24 nt (11, 39) (Fig. 1A). Both the different lengths and different nucleotide sequences might contribute to differential transcription attenuation. To analyze the effect of the different RV IGRs on transcription of mRNAs, we used the bicistronic model RNA SDI-CL(NP) (16). In SDI-CL(NP) the upstream chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene and the downstream firefly luciferase gene are separated by the RV N/P gene border sequence (Fig. 1A). By site-directed mutagenesis, the N/P IGR dinucleotide was exchanged with the 5- and 24-nt IGRs of the P/M, M/G, and G/L gene borders.

FIG. 1.

(A) Sequences of transcription signals and IGRs from the four RV gene borders and organization of the minigenome used for analysis of IGRs. Consensus sequences for stop/polyadenylation and transcription reinitiation are indicated in plus strand orientation. The bicistronic minigenome SDI-CL(NP) contains the full N/P gene border between the CAT and firefly luciferase reporter genes. The indicated N/P signal sequences were flanked upstream by 71 nt derived from the 3′-terminal part of the N gene. The 55-nt 5′-noncoding sequence (ncds) of the luciferase mRNA comprised 16 nt derived from the 5′ ncds of the RV P mRNA, including the 9-nt start signal, followed by 39 nonviral nucleotides. SDI-CL(NP) was used to derive mutants in which the 2-nt IGR was replaced with the 5-, 5-, and 24-nt IGRs from other gene borders. (B) Transcription of indicated model genomes in cells coinfected with a helper RV. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated 2 days postinfection and analyzed by Northern hybridization and phosphorimaging with CAT gene- and luciferase gene-specific probes. The locations of monocistronic mRNAs and bicistronic CAT/luciferase mRNA (CAT/luci) are indicated. The relative levels of downstream luciferase mRNA were calculated after normalizing with CAT mRNA and defining the SDI-CL(NP) luciferase mRNA level as 100%. Transcriptional readthrough is given as the percentage of bicistronic CAT/luciferase mRNA to CAT mRNA.

The resulting model RNAs were rescued from cDNA after transfection of cells by complementation with RV N, P, M, G, and L proteins as described previously (34). Virus-like particles released into the supernatants were transferred onto fresh BSR cell cultures after 3 days. One hour later, cells were superinfected with RV SAD Ambi helper virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. SAD Ambi is a recombinant ambisense gene expression RV that preferentially supports replication of SDI-like minigenome RNPs (15, 16). Two additional passages, each including superinfection with additional SAD Ambi helper virus at an MOI of 1, were performed in order to allow maximal minigenome amplification. Total RNA was isolated from cells 2 days after the third passage, and polyadenylated mRNA was enriched. After agarose gel electrophoresis and Northern blotting, poly(A)+ RNAs were analyzed by hybridization with CAT gene- and luciferase gene-specific DNA probes (Fig. 1B). Transcription from SDI-CL(NP), which comprises the authentic N/P gene border sequence, yielded abundant amounts of monocistronic CAT and luciferase mRNA. Transcription termination at the gene border was highly efficient, as only minor levels of bicistronic CAT/luciferase readthrough mRNAs were present in infected cells, amounting to 1.3% of monocistronic CAT mRNA. Reinitiation of luciferase mRNA transcription occurred efficiently. After replacement of the authentic N/P intergenic dinucleotide with the IGR nucleotides of the P/M, M/G, and G/L gene borders, transcription of the upstream CAT gene remained comparable to that of SDI-CL(NP). Only moderate increases of readthrough transcripts to levels of 3.0, 2.8, and 2.4%, respectively, of monocistronic CAT mRNAs were observed. This indicated that the efficiency of transcription termination was not markedly affected by exchange of the IGRs.

An obvious effect, however, was obtained on reinitiation of transcription of the downstream luciferase gene. With the amount of luciferase mRNA from SDI-CL(NP)-infected cells defined as 100%, the amounts of luciferase mRNA in SDI-CL(igPM)- and SDI-CL(igMG)-infected cells decreased to similar levels of 78 and 81%, respectively. In cells infected with SDI-CL(igGL) containing the 24-nt IGR, luciferase gene transcription dramatically decreased to 11% (Fig. 1B). This is reminiscent of the steep gradient step that is observed at the RV G/L gene border. These data indicated that the lengths of nontranscribed IGRs constitute an important factor in regulating RV gene transcription and that the 24-nt G/L IGR is a critical factor in the downregulation of RV L gene transcription.

Exchange of gene borders in recombinant RV.

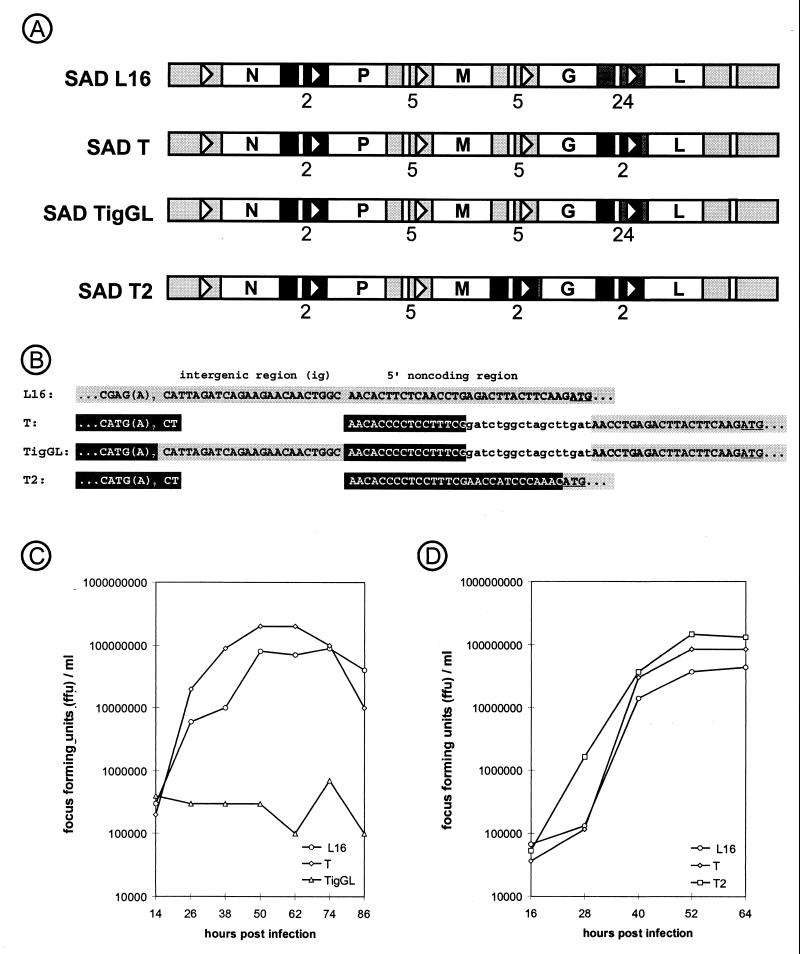

To confirm that transcription of the RV RNA polymerase gene is attenuated by the 24-nt G/L IGR sequence, we constructed a full-length RV cDNA, pSAD T, in which the complete G/L gene border of RV SAD L16 was replaced with a copy of the N/P gene border sequence which had proved optimal in the minigenome transcription assay (Fig. 2A). On the basis of pSAD T another construct was made by replacing the 2-nt IGR from the new gene border with the 24-nt G/L IGR nucleotides (pSAD TigGL). The resulting gene border corresponded to that of SDI-CL(igGL), which performed worst in the minigenome assays. Both full-length cDNA constructs were successfully rescued into viable recombinant virus. Virus stock solutions were prepared after three passages following rescue as described previously (34). In the third passage, SAD T already reached a titer of 4 × 108 focus forming units (FFU) per ml of cell culture supernatant. In contrast, two independent clones of SAD TigGL yielded titers of only 106 and 2.5 × 106 FFU/ml, indicating a reduced ability to propagate. This was confirmed by infections at defined MOIs and analysis of growth curves (Fig. 2C). Compared with the wt virus SAD L16, SAD TigGL was attenuated in growth, and maximum virus yield remained below 106 FFU/ml. To exclude the possibility that the poor growth of the two SAD TigGL isolates was due to incidental damages introduced into the genome, revertants were generated by reexchanging the G/L IGR nucleotides. Both revertants were indistinguishable in growth and RNA synthesis from SAD T, confirming that the 24-nt IGR was responsible for the strikingly reduced L gene transcription and the extremely poor growth of SAD TigGL.

FIG. 2.

(A) Genome organization of wt RV (SAD L16) and recombinant viruses. In SAD T, 52 nt of the wt G/L gene border comprising the authentic signal sequences were replaced with 145 nt encoding the N/P gene border. The new 53-nt 5′-noncoding sequence (ncds) of the L mRNA consists of 16 nt derived from the 5′ ncds of P mRNA, followed by 17 nonviral nucleotides and 20 nt from the authentic 30-nt L ncds. In SAD TigGL the N/P gene border copy was modified to contain the 24-nt IGR derived from the SAD L16 G/L gene border. Due to replacement of a 510-nt sequence comprising the complete pseudogene region Ψ and the 5′ ncds of the L mRNA with a 145-nt sequence comprising the N stop and P start signals, in SAD T2 the entire 29-nt 5′ noncoding region of the L gene is derived from the P gene. In addition, 152 nt of the M/G gene border were replaced with an additional copy of the N/P gene border, resulting in a 35-nt G mRNA 5′ ncds consisting of 18 nt derived from the P mRNA 5′ ncds followed by 11 nonviral nucleotides and 6 nt of the authentic G mRNA 5′ ncds. (B) Detailed sequence of the novel G/L gene borders. Shaded boxes, nucleotides derived from the authentic G/L gene border; black boxes, nucleotides derived from the RV N/P gene border. All nonviral sequences are in lowercase. The L initiation codon is underlined. (C) Single-step growth curve of wt RV SAD L16, SAD T, and SAD TigGL. BSR cells were infected at an MOI of 1, and cell culture supernatants were collected at 12-h intervals. Infectious virus titers were determined as FFU by end point dilutions and titration on BSR cells. (D) Single-step growth curves of SAD L16, SAD T, and SAD T2. BSR cells were infected with viruses, and cell culture supernatants were collected at 12-h intervals. Infectious virus titers were determined as described for panel B.

Thus, the 24-nt IGR flanked by the N/P-derived transcription signals resulted in a considerable attenuation of virus growth, presumably by limiting L gene transcription. In contrast, SAD T containing the authentic 2-nt N/P gene border with 2 IGR nucleotides grew faster than the parental SAD L16, presumably by enhanced L gene expression. Indeed, infectious titers of SAD T exceeded those of SAD L16 by factors of 3.3, 9.0, and 2.5 at 26, 38, and 50 h postinfection, respectively. As the recombinant virus SAD L16 corresponds to SAD B19, which is widely used as a live vaccine and which is very well adapted to optimal growth in BSR cell culture, the improved growth characteristics of SAD T were notable.

To further enhance L expression, which was assumed to be responsible for the improved growth rate, additional recombinant RVs were generated. The introduction of the N/P gene border copy into SAD T resulted in a chimeric L gene in which the transcription start signal and a few nucleotides derived from the P gene were fused to L 5′-noncoding sequences (Fig. 2A and B). As the chimeric gene border of SAD TigGL resulted in even slower growth than the wt G/L border, we constructed a virus in which the entire 5′-noncoding L sequence exactly matched the 29-nt 5′-noncoding region of the P gene (SAD TB; not shown). In this virus, part of the 3′-noncoding region of the SAD L16 G mRNA, which is known as pseudogene Ψ, was also deleted. This modification, however, was previously shown not to have an effect on L gene transcription and virus growth (7, 26, 34). In addition, the M/G gene border of SAD TB was replaced by a copy of the N/P gene border to give rise to SAD T2. The recombinant RVs SAD TB and SAD T2 (Fig. 2A) were recovered from cDNA in a vaccinia virus-free T7 expression system (16) using cell line BSR T7/5, which constitutively expresses T7 RNA polymerase (6). No differences in growth characteristics between SAD TB and SAD T2 were observed, so only SAD T2 was used for further comparison with the previously rescued constructs. After infection of BSR cells at an MOI of 1, SAD T2 titers were 12- and 14-fold higher than those of SAD L16 and SAD T at 28 h postinfection, indicating very rapid replication of the virus (Fig. 2D). Maximum titers of SAD T2 were reached at 52 h and exceeded those of SAD T and SAD L16 by 1.8- and 4-fold, respectively.

RNA synthesis of recombinant viruses.

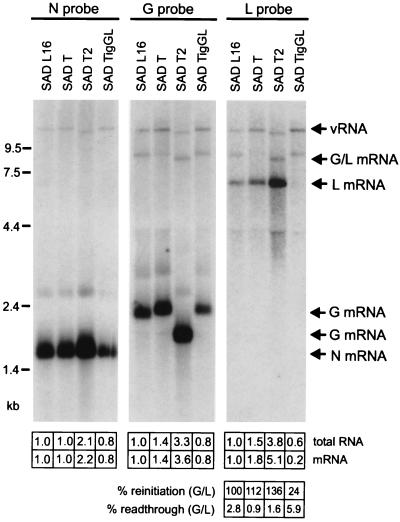

To investigate whether the accelerated growth of SAD T and SAD T2 correlated with enhanced L transcription and L protein expression, BSR cells were infected with the recombinant viruses or SAD L16 at an MOI of 1. RNA was isolated from infected cells 24 h postinfection and analyzed by Northern hybridization with RV-specific DNA probes (Fig. 3). Hybridizations with an RV L gene-specific probe confirmed that monocistronic L mRNA was most abundant in SAD T2-infected cells, followed by SAD T-infected cells. Compared to results for SAD L16-infected cells, 5.1- and 1.8-fold increases, respectively, were determined by phosphorimaging. In contrast, the poorly growing SAD TigGL yielded fivefold-smaller amounts of L mRNA than SAD L16. This strongly suggested that limiting amounts of polymerase are indeed responsible for the observed attenuated phenotype of SAD TigGL. Comparing SAD TigGL and SAD T, which differed exclusively in the G/L intergenic sequence, the L mRNA amount was ninefold higher in SAD T-infected cells than in SAD TigGL-infected cells. Thus, the 24-nt IGR in SAD TigGL alone caused strong attenuation of downstream L gene transcription.

FIG. 3.

RNA synthesis from recombinant RV. Total RNA from cells infected with the viruses indicated was analyzed 1 day postinfection by Northern hybridization with nick-translated DNA probes recognizing RV N, G, and L. The positions of mRNAs and full-length virus RNA (vRNA) are indicated. RNA was quantified by phosphorimaging, and relative values are given with respect to SAD L16 RNAs (1.0) at the bottom. Most important is the increase of L mRNA in SAD T and SAD T2 by factors of 1.8 and 5.1, respectively, and the decrease of L mRNA in SAD TigGL to 20% of SAD L16 levels, which is accompanied by augmented G/L readthrough. Reinitiation of L transcription was calculated as the ratio of L/G transcripts, defining SAD L16 reinitiation as 100%. Readthrough is given as the percentage of bicistronic G/L transcripts with respect to the sum of monocistronic G and bicistronic M/G transcripts. For details see the text.

Most of the effect was due to altered reinitiation of L transcription. We compared the amounts of monocistronic L mRNA to the amounts of upstream G transcripts, including G mRNA and bicistronic M-plus-G RNA, and defined the L/G transcript ratio of SAD L16 as 100%. Increased L reinitiations of 136 and 112% were determined for SAD T2 and SAD T, respectively. In contrast, a remarkably reduced reinitiation of 24% was measured for SAD TigGL. Altered readthrough leading to bicistronic G-plus-L transcripts also slightly contributed to the different L mRNA amounts. Compared to the 2.8% readthrough transcripts produced by SAD L16, reductions to 0.9 and 1.6% were observed in SAD T and SAD T2, respectively. In contrast, an increased readthrough rate of 5.9% was determined for SAD TigGL (Fig. 3). Thus, replacement of the 2-nt IGR of SAD T with the 24-nt IGR resulted in a 6.5-fold increase of readthrough transcription in SAD TigGL-infected cells.

Not only L gene transcription but also general RNA synthesis was exaggerated in SAD T- and SAD T2-infected cells, as illustrated by RV G and N gene-specific hybridization experiments. Monocistronic N and G mRNA levels in SAD T2 were 2.2- and 3.6-fold higher, respectively, than those of SAD L16. Also, in SAD T-infected cells, a 1.4-fold increase of G mRNA was observed. As could be expected, the small amounts of L polymerase in SAD TigGL-infected cells led to reduced levels of N and G mRNAs, each approaching 80% of SAD L16 levels.

Protein synthesis from recombinant viruses.

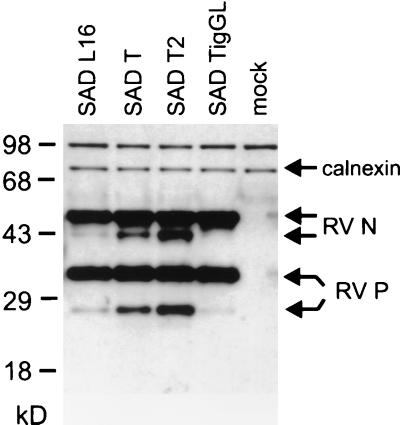

The higher transcript levels in SAD T- and SAD T2-infected cells resulted in larger amounts of virus proteins in infected cells as determined by Western blot analyses. N and P proteins were detected with a serum raised against RV ribonucleoprotein complexes (Fig. 4). Calnexin, visualized by a monoclonal antibody, was used as an internal cellular marker protein. Both N- and P-specific signals were more intense in SAD T- and SAD T2-infected cells, indicating that the additional mRNAs were being translated into proteins. Interestingly, marked increases were observed only for the small forms of N and P proteins, while the signals representing the higher-molecular-weight forms were quite constant. The low-molecular-weight forms probably represent immature or N-terminally truncated virus proteins (8, 22), whereas the higher-molecular-weight forms represent the proteins which are incorporated into RNPs (unpublished data). The apparent bias toward increase of the shorter proteins may reflect slow processing or intracellular inactivation of these forms, while mature proteins are rapidly assembled into RNPs and virions and are thus rapidly exported into the supernatant.

FIG. 4.

Exaggerated protein expression from recombinant RV. Extracts from BSR cells infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 1 were analyzed 1 day postinfection by Western blotting. RV N and P proteins were visualized by using the polyclonal rabbit serum S50. Increasing amounts of N and P proteins are observed in SAD T- and SAD T2-infected cells, whereas protein expression of SAD TigL is reduced. Calnexin was used as a loading control. mock, noninfected cells.

Growth of SAD T and SAD T2 induces CPE.

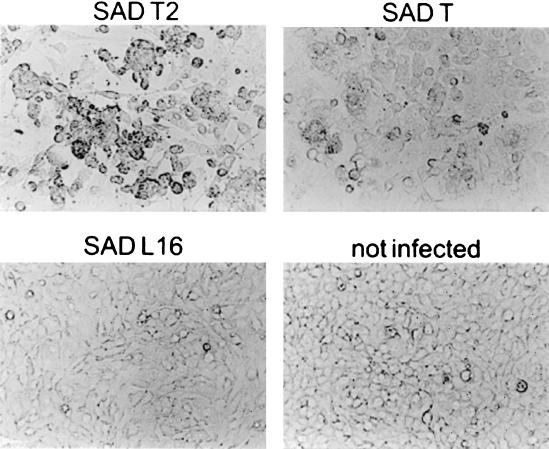

The general increase of RNA synthesis and protein expression in SAD T and SAD T2 not only resulted in higher virus titers but also had obvious effects on the infected cells. In contrast to SAD L16, which grows in BSR cell culture without exhibiting obvious cytopathic effects (CPE), SAD T and SAD T2 induced a strong CPE (Fig. 5). Three days after infection with SAD T2 at an MOI of 1 the cell monolayer was widely destroyed and large syncytia and cell aggregates were predominant. Interestingly, SAD T, with a less vigorous gene expression than SAD T2, caused less damage but still was clearly more cytopathic than SAD L16. Thus, the grade of CPE appears to directly correlate with the level of virus gene expression. As indicated by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling assays (ApopTaq; Intergen), induction of apoptosis in BSR cells was not involved.

FIG. 5.

Induction of CPE by recombinant RVs. Monolayers of BSR cells were infected with wt RV (SAD L16) and recombinant viruses SAD T and SAD T2 at an MOI of 1. Three days postinfection cells were analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy. The severity of CPE was roughly correlated with the enhancement of gene expression.

Pathogenicity of SAD T2 and SAD L16 in mice.

Notably, in spite of heavily damaging cells, both SAD T and SAD T2 yielded higher virus titers than SAD L16 during the course of infection of the cell culture. Under the assumption that levels of gene expression, speed of replication, and quantity of virion production are important for virus evolution in cell culture, the wt SAD L16 is obviously a suboptimal virus. To investigate the behavior of the recombinant viruses in vivo, 3 × 104 FFU of SAD L16, SAD T, or SAD T2 were injected in the footpads of 3-week-old CD-1 mice. After 10 and 11 days two of five mice inoculated with SAD T2 showed paralysis of both hindlimbs. In contrast, SAD L16- and SAD T-infected mice exhibited no clinical signs even 6 weeks after inoculation. Mice with clinical symptoms were killed, and brain material was screened for the presence of virus; from both mouse brains virus could be isolated, indicating that the virus reached the central nervous system. In a second experiment, a higher virus dose of 1.2 × 106 FFU/mouse was used to inoculate footpads of 3-week old CD-1 mice. Again, two of five mice inoculated with SAD T2 showed paralysis of hindlimbs at days 7 and 9. In both cases, virus isolation from brains at day 9 after inoculation was positive. In contrast, all five mice inoculated with SAD L16 showed no symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Sequential synthesis of mRNAs according to the stop/start mechanism is a common feature of all nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses and provides a unique, efficient, and simple mechanism to differentially express individual genes from a contiguous virus genome. The major determinant of gene expression is the relative distance of a gene from the single 3′-terminal promoter (40). The second determinant is the steepness of the transcript gradient, which is a result of attenuation at gene borders. Some viruses, such as members of the Paramyxovirinae subfamily and the rhabdovirus VSV, have nearly identical gene borders suggesting rather even transcript gradients. The gene borders in others, however, may vary considerably, for example, in pneumoviruses, such as human respiratory syncytial virus (HSRV) and bovine respiratory syncytial virus, in paramyxoviruses such as simian virus 5 (SV5), and in the rhabdovirus RV. Obviously, variable gene borders can provide means for a more refined regulation of gene expression. We show here that the different RV IGRs profoundly differ in supporting transcription reinitiation. By manipulating gene borders, the balanced expression of the five virus proteins could be altered and novel viruses with distinct phenotypes were generated. Most remarkably, it was possible to create viruses superior to parental viruses in terms of growth kinetics and virus yield.

As demonstrated by reporter gene RNA assays, the RV IGRs have a considerable effect on the synthesis of downstream gene transcripts. Compared to the N/P intergenic dinucleotide, the 5-, 5-, and 24-nt intergenic nucleotides from the P/M, M/G, and G/L gene borders, respectively, caused a decrease of downstream luciferase gene expression. Although a slight increase in readthrough transcripts was observed, this was due not to a failure of the polymerase in correct termination of the upstream CAT gene mRNA but rather to a failure in recognizing the downstream transcription initiation signal. The synthesis of downstream RNAs was reduced to levels of 78, 81, and 11% of that obtained with the N/P intergenic dinucleotide. These values appear to directly correlate with increasing length of the IGRs of 5, 5, and 24 nt, respectively. The similar reinitiation rates of the P/M and M/G IGRs, which only differ in nucleotide sequence, indicated that the major regulatory factor in RV transcription attenuation is the lengths of the IGRs, i.e., the distance from the stop/polyadenylation signal to the restart signal. However, at this point we are not excluding a minor influence of the specific sequence of the 5-nt RV IGRs on polymerase activities.

The function of the IGR as a necessary spacer between the stop and the restart signals is emphasized by the previous finding that gene borders lacking any intergenic nucleotide result in abrogation of reinitiation, whereas termination occurs quite efficiently, both in RV and in VSV (5, 15). In both systems reinitiation is only partially restored when a single nucleotide is introduced between the A stretch of the polyadenylation signal and the consensus restart signal (5, 36). Thus, the length of the RV IGR is a major determinant in transcription attenuation, and a length of 2 nt, as found in the N/P gene border, appears to be optimal. This can also be concluded from studies of VSV minigenomes. After elongation of the VSV consensus IGR dinucleotide up to 21 nt, a decrease in reinitiation was observed, partially due to abortive attempts of reinitiation at inappropriate sequences within the long IGR (37, 38). In addition, the identity of added nucleotides had some effect on reinitiation efficiency, although no obvious sequence pattern could be correlated (4, 37). In contrast to these observations with rhabdoviruses, a less important role for the IGR length is suggested for several paramyxoviruses. IGRs of HRSV of the Pneumovirinae subfamily are highly variable in length but did not differ in reinitiation of transcription in an artificial minigenome assay (23). Also, in the rubulavirus SV5 the lengths of IGRs alone did not correlate with attenuation (19).

As anticipated from the weak downstream transcription in the RV minigenome, the 24-nt G/L IGR of the wt RV SAD L16 should be responsible for attenuating transcription of the L gene in infected cells. To address this hypothesis and to see whether RVs that overexpress L can be generated, we exchanged the G/L gene border with the N/P gene border, which caused the least attenuation in the reporter gene RNA assays. Indeed, SAD T and SAD T2 produced more translatable L mRNA than wt virus SAD L16. This resulted in a general increase of RNA synthesis and virus protein expression. More surprisingly, the recombinant viruses grew faster and yielded higher infectious titers than the parental SAD L16, although the latter is considered to be very well adapted to growth in BSR cell cultures.

Exaggerated L mRNA transcription, polymerase expression, and gain of fitness were already observed for SAD T. As SAD T and SAD TigGL differ only in having 2 and 24 IGR nucleotides, respectively, the long 24-nt IGR is the crucial factor in the observed ninefold difference in L mRNA transcription. However, L mRNA levels for SAD L16, which also has a 24-nt IGR, were fivefold higher than those for SAD TigGL. Obviously, the combination of N/P transcription signals and the G/L intergenic sequence is less efficient than the authentic G/L gene border, both in reinitiation (24% of SAD L16 level) and in termination (twofold-increased readthrough). Apparently, the individual nontranscribed RV IGR has to fit somehow into its sequence environment for optimal function. This was also reported to apply in other viruses, such as HRSV (18), VSV (37), and SV5 (30).

These considerations were taken into account in the design of SAD T2, in which the remainder of the L-derived 5′-nontranslated sequence of SAD T was replaced with the corresponding sequence of the P gene. In addition, the M/G gene border sequence was exchanged with the N/P gene border fragment to enhance G gene transcription and thereby also transcription of the downstream L gene. The deletion of the G pseudogene sequence was not considered important in this respect, as it was previously shown that it has no detectable effect on transcription and growth of SAD L16 (7, 26, 34).

Indeed, the modifications introduced in SAD T2 resulted in a further-improved virus growth and an overall increase of RNA synthesis. A marked upregulation of G mRNA transcription by the N/P gene border introduced upstream of the G gene could not be demonstrated. Moreover, a recombinant RV that was identical with SAD T2 but that contained the wt M/G gene border sequence showed nearly the same growth characteristics and mRNA levels as SAD T2 (not shown). Thus, we conclude that the higher gene expression from SAD T2 than from SAD T is caused mainly by the P gene-derived 5′-noncoding region. Indeed, compared to the situation in SAD T, 2.8-fold-higher levels of L mRNA were present in SAD T2. Assuming equal stability of the L mRNAs, the reinitiation rate for the SAD T2 G/L gene border was increased by 24%.

The RV N/P gene border fragment promoted highly efficient synthesis of a downstream gene in the reporter minigenome system. It does so also in the context of full-length RV vectors, where it has been repeatedly used to express additional genes introduced downstream of G (7, 26) (unpublished experiments). In all these cases with different sequence environments the downstream gene mRNA levels were not much reduced compared to the upstream G mRNA levels. As found here with the L gene, the N/P gene border was also able to enhance L mRNA synthesis, but not nearly to the approximately 10-fold-higher levels that could be expected from experiments with the minigenomes or with the expression of foreign genes from RV vectors. This indicates that, besides downregulation of transcription reinitiation, other mechanisms are active in keeping L expression low, such as the slow processivity of the polymerase on the L gene template or the short half-life of L mRNA. Studies on recombinant SV5 showed also that L mRNA upregulation was very limited, and the authors also argue in favor of other mechanisms being involved (19).

Attenuation of L gene expression seems to be a common feature of many nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses. A striking way to achieve L downregulation has been identified in respiratory syncytial virus: the M2 and L genes overlap such that the M2 stop/polyadenylation signal is located downstream of the L start signal (9). A long nonconserved G/L IGR of more than 20 nt is a common feature of all RV isolates and also of more distantly related Lyssavirus serotypes, such as Mokola and Lagos Bat viruses (25). In cell culture-adapted RV strains ERA and PV additional stop/polyadenylation signal-like sequences within the long G 3′-noncoding sequence, which direct the termination of approximately 50% of G transcripts, have been identified (12, 27, 39). It can be concluded that polymerases terminating at this site are not able to reinitiate at the L transcription restart signal which is located approximately 400 nt downstream, leading to further reduction of L mRNA. Expression experiments with VSV and analysis of recombinant SV5 have indicated that overexpression of L polymerase inhibits virus replication (28, 35). In contrast, and similar to our results, increased expression of downstream genes after modification of the Sendai virus M/F gene border resulted in faster replication in cell culture (21).

An explanation for maintenance of L gene downregulation in RV strains well adapted to cell culture, such as SAD, is not close at hand, since mutated viruses expressing more L have clear advantages in cell culture. However, L attenuation in street viruses may offer a considerable advantage. In contrast to the parental virus, SAD L16, the recombinant viruses SAD T and SAD T2 showed CPE increasing with the level of gene expression and replication. It is unlikely that a pronounced CPE is an advantage for RV dissemination in the field, although virus replication is faster and yields higher virus titers. Mouse footpad injection experiments showed that SAD T2 is able to cause symptoms in 40% of injected mice, while SAD L16 is not. SAD T2 virus could be isolated from brains of these animals. Thus, although overexpression of virus antigens and cytopathogenicity might provoke a more pronounced immune reaction, the virus was able to reach the central nervous system. Faster growth and the induction of a CPE in a pathogenic street virus could therefore result in a very rapid course of disease and killing of the animal prior to virus transmission to a new host. This may also apply to Sendai virus, as overexpressing recombinants were found more pathogenic for mice than standard virus (21).

In the past, the function of RV gene borders in transcription regulation was only deduced from sequence comparisons. The availability of recombinant RV with upregulated gene expression provided evidence that, beside the prime factor of transcription regulation, namely, the well-conserved gene order, a second factor, namely, the well-conserved gene order, a second factor, namely, the attenuation by specific gene border sequences, considerably contributes to regulation of RV gene expression. With regard to our special interest in the development of RV vectors for gene delivery, the possibility to increase virus gene expression by upregulating L gene transcription offers the opportunity to create novel virus vectors which are optimized for high gene expression and virus production. In particular, upregulated L gene transcription may compensate for attenuating effects caused by insertion of multiple foreign cistrons into the virus genome. It was previously shown that the coding capacity of RV vectors can be increased by using ambisense RV or preferentially replicating model genomes similar to defective interfering particles (15, 16). Overexpression of the viral polymerase offers an additional way to create optimized high-capacity rhabdovirus vectors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 455-A3).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham G, Banerjee A K. Sequential transcription of the genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:1504–1508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.5.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball L A, White C N. Order of transcription of genes of vesicular stomatitis virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:442–446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee A K. Transcription and replication of rhabdoviruses. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:66–87. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.1.66-87.1987. . (Erratum, 51:299.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr J N, Whelan S P, Wertz G W. cis-Acting signals involved in termination of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNA synthesis include the conserved AUAC and the U7 signal for polyadenylation. J Virol. 1997;71:8718–8725. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8718-8725.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barr J N, Whelan S P, Wertz G W. Role of the intergenic dinucleotide in vesicular stomatitis virus RNA transcription. J Virol. 1997;71:1794–1801. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1794-1801.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz U J, Finke S, Conzelmann K K. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. J Virol. 1999;73:251–259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.251-259.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceccaldi P E, Fayet J, Conzelmann K K, Tsiang H. Infection characteristics of rabies virus variants with deletion or insertion in the pseudogene sequence. J Neurovirol. 1998;4:115–119. doi: 10.3109/13550289809113489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenik M, Chebli K, Blondel D. Translation initiation at alternate in-frame AUG codons in the rabies virus phosphoprotein mRNA is mediated by a ribosomal leaky scanning mechanism. J Virol. 1995;69:707–712. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.707-712.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins P L, Olmsted R A, Spriggs M K, Johnson P R, Buckler-White A J. Gene overlap and site-specific attenuation of transcription of the viral polymerase L gene of human respiratory syncytial virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5134–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conzelmann K K. Nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses: genetics and manipulation of viral genomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1998;32:123–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conzelmann K K, Cox J H, Schneider L G, Thiel H J. Molecular cloning and complete nucleotide sequence of the attenuated rabies virus SAD B19. Virology. 1990;175:485–499. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90433-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conzelmann K K, Cox J H, Thiel H J. An L (polymerase)-deficient rabies virus defective interfering particle RNA is replicated and transcribed by heterologous helper virus L proteins. Virology. 1991;184:655–663. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90435-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conzelmann K K, Schnell M. Rescue of synthetic genomic RNA analogs of rabies virus by plasmid-encoded proteins. J Virol. 1994;68:713–719. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.713-719.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emerson S U. Reconstitution studies detect a single polymerase entry site on the vesicular stomatitis virus genome. Cell. 1982;31:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finke S, Conzelmann K K. Ambisense gene expression from recombinant rabies virus: random packaging of positive- and negative-strand ribonucleoprotein complexes into rabies virions. J Virol. 1997;71:7281–7288. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7281-7288.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finke S, Conzelmann K K. Virus promoters determine interference by defective RNAs: selective amplification of mini-RNA vectors and rescue from cDNA by a 3′ copy-back ambisense rabies virus. J Virol. 1999;73:3818–3825. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3818-3825.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuerst T R, Niles E G, Studier F W, Moss B. Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8122–8126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardy R W, Harmon S B, Wertz G W. Diverse gene junctions of respiratory syncytial virus modulate the efficiency of transcription termination and respond differently to M2-mediated antitermination. J Virol. 1999;73:170–176. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.170-176.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He B, Lamb R A. Effect of inserting paramyxovirus simian virus 5 gene junctions at the HN/L gene junction: analysis of accumulation of mRNAs transcribed from rescued viable viruses. J Virol. 1999;73:6228–6234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6228-6234.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iverson L E, Rose J K. Localized attenuation and discontinuous synthesis during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. Cell. 1981;23:477–484. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kato A, Kiyotani K, Hasan M K, Shioda T, Sakai Y, Yoshida T, Nagai Y. Sendai virus gene start signals are not equivalent in reinitiation capacity: moderation at the fusion protein gene. J Virol. 1999;73:9237–9246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9237-9246.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawai A, Toriumi H, Tochikura T S, Takahashi T, Honda Y, Morimoto K. Nucleocapsid formation and/or subsequent conformational change of rabies virus nucleoprotein (N) is a prerequisite step for acquiring the phosphatase-sensitive epitope of monoclonal antibody 5-2-26. Virology. 1999;263:395–407. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo L, Fearns R, Collins P L. The structurally diverse intergenic regions of respiratory syncytial virus do not modulate sequential transcription by a dicistronic minigenome. J Virol. 1996;70:6143–6150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6143-6150.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo L, Grosfeld H, Cristina J, Hill M G, Collins P L. Effects of mutations in the gene-start and gene-end sequence motifs on transcription of monocistronic and dicistronic minigenomes of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 1996;70:6892–6901. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6892-6901.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mebatsion T, Cox J H, Conzelmann K-K. Molecular analysis of rabies related viruses from Ethiopia. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1993;60:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mebatsion T, Schnell M J, Cox J H, Finke S, Conzelmann K K. Highly stable expression of a foreign gene from rabies virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7310–7314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morimoto K, Ohkubo A, Kawai A. Structure and transcription of the glycoprotein gene of attenuated HEP-Flury strain of rabies virus. Virology. 1989;173:465–477. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90559-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattnaik A K, Wertz G W. Replication and amplification of defective interfering particle RNAs of vesicular stomatitis virus in cells expressing viral proteins from vectors containing cloned cDNAs. J Virol. 1990;64:2948–2957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2948-2957.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pringle C R, Easton A J. Monopartite negative strand RNA genomes. Semin Virol. 1997;8:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rassa J C, Parks G D. Highly diverse intergenic regions of the paramyxovirus simian virus 5 cooperate with the gene end U tract in viral transcription termination and can influence reinitiation at a downstream gene. J Virol. 1999;73:3904–3912. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3904-3912.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose J K. Complete intergenic and flanking gene sequences from the genome of vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell. 1980;19:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schnell M J, Buonocore L, Whitt M A, Rose J K. The minimal conserved transcription stop-start signal promotes stable expression of a foreign gene in vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 1996;70:2318–2323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2318-2323.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnell M J, Conzelmann K K. Polymerase activity of in vitro mutated rabies virus L protein. Virology. 1995;214:522–530. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnell M J, Mebatsion T, Conzelmann K K. Infectious rabies viruses from cloned cDNA. EMBO J. 1994;13:4195–4203. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubert M, Harmison G G, Richardson C D, Meier E. Expression of a cDNA encoding a functional 241-kilodalton vesicular stomatitis virus RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7984–7988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stillman E A, Whitt M A. Mutational analyses of the intergenic dinucleotide and the transcriptional start sequence of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) define sequences required for efficient termination and initiation of VSV transcripts. J Virol. 1997;71:2127–2137. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2127-2137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stillman E A, Whitt M A. The length and sequence composition of vesicular stomatitis virus intergenic regions affect mRNA levels and the site of transcript initiation. J Virol. 1998;72:5565–5572. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5565-5572.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stillman E A, Whitt M A. Transcript initiation and 5′-end modifications are separable events during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. J Virol. 1999;73:7199–7209. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7199-7209.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tordo N, Poch O, Ermine A, Keith G, Rougeon F. Walking along the rabies genome: is the large G-L intergenic region a remnant gene? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3914–3918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wertz G W, Perepelitsa V P, Ball L A. Gene rearrangement attenuates expression and lethality of a nonsegmented negative strand RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]