Abstract

Despite the global ban on organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) since the 1970s, their use continues in many developing countries, including Ethiopia, primarily due to the lack of viable alternatives and weak regulations. Nonetheless, the extent of contamination and the resulting environmental and health consequences in these countries remain inadequately understood. To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of reported concentrations (n=398) of OCPs (n=30) in distinct yet interconnected water matrices: water, sediment, and biota in Ethiopia. Our analysis revealed a notable geographical bias, with higher concentrations found in sediments (0.074–1161.2 µg/kg), followed by biota (0.024–1003 µg/kg) and water (0.001–1.85 µg/L). Moreover, DDTs, endosulfan, and hexachlorohexenes (HCHs) were among the most frequently detected OCPs in higher concentrations in Ethiopian waters. The DDT metabolite p,p′-DDE was commonly observed across all three matrices, with concentrations in water birds reaching levels up to 57 and 143,286 times higher than those found in sediment and water, respectively. The findings showed a substantial potential for DDTs and endosulfan to accumulate and biomagnify in Ethiopian waters. Furthermore, it was revealed that the consumption of fish contaminated with DDTs posed both non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks while drinking water did not pose significant risks in this regard. Importantly, the issue of OCPs in Ethiopia assumes even greater significance as their concentrations were found to be eight times higher than those of currently used pesticides (CUPs) in Ethiopian waters. Consequently, given the ongoing concerns about OCPs in Ethiopia, there is a need for ongoing monitoring, implementation of sustainable mitigation measures, and strengthening of OCP management systems in the country, as well as in other developing countries with similar settings and practices.

Keywords: Bioaccumulation factor, DDT, Developing countries, Health risk, Legacy pesticide, Meta-analysis

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Analysis of organochlorines in Ethiopian water, sediment and biota was conducted.

-

•

DDTs, endosulfan, and hexachlorohexenes were among the most frequently detected.

-

•

Organochlorines were found to bioaccumulate and biomagnify in local food webs.

-

•

Consumption of some fish species posed significant health risks.

1. Introduction

Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) are a group of synthetic chemicals that were widely used in the past to control pests in agriculture and combating disease vectors in public health. Representative OCP compounds include dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), hexachlorohexene (HCH), lindane, endosulfan, dieldrin, methoxychlor, chlordane, toxaphene, and dicofol. These compounds vary in their chemical structure and mechanisms of action [20], [28], [29]. In general, OCPs are highly toxic, resistant to degradation, capable of long-range transport, and prone to bioaccumulation and biomagnification in the environment, making them persistent organic pollutants (POPs) of concern [29], [5], [53], [54]. Consequently, they have become ubiquitous in the environment, being found even in remote locations like polar environments and the deep sea [57], [72], [86].

OCPs enter water resources through various routes, primarily including surface runoff, erosion, atmospheric drift, and deposition [3], [60]. Once in water bodies, OCPs can sorb to suspended and particulate organic matter, transfer to sediments, or enter the aquatic food chain. This can lead to bioaccumulation and, over time, biomagnification in top predators, including water birds and humans [10], [29], [9]. Additionally, OCPs can cause mortality, reproductive failure, eggshell thinning, and immune system suppression among aquatic organisms [40], [65], [70]. Moreover, epidemiological evidence suggests that human exposure to OCPs results in various health issues, including reproductive dysfunction, endocrine disruption, immune system dysfunction, and cancer [33], [35], [39], [58], [85].

Due to their significant impact on the environment and human health, countries have implemented bans on the production and use of OCPs since the 1970s (e.g., the Stockholm Proclamation adopted in 2001). As a result, there has been a substantial decrease in their market share as they have been replaced by supposedly less toxic alternatives such as organophosphates and pyrethroids [31], [63]. However, despite the bans, the use of OCPs has persisted in developing countries, primarily driven by their high efficiency-to-cost ratio and the lack of affordable alternatives [31], [54], [71], [8]. Although these pesticides are purportedly used for vector-borne disease control in these countries, reports on their illegal use in agricultural activities also exist [4], [47], [73]. Importantly, the use of OCPs in these countries does not appear to be ceasing soon due to the increasing incidence of vector-borne diseases, pest resistance, and weak regulatory policies to control their usage [11], [31]. Therefore, OCPs continue to be a concern in developing countries, including Ethiopia.

In this regard, studies have indicated a lack of scientific knowledge concerning the actual field concentrations of OCPs and their effects on non-target organisms in developing countries [11], [22], [36]. Most of the available evidence is derived from studies conducted in temperate regions, and the limited studies carried out in developing countries have primarily focused on identifying research hotspots and reporting OCP concentrations without conducting detailed analyses (e.g., [21], [54]). To address these gaps, we conducted an analysis of OCP contamination in water resources in Ethiopia, a tropical country. We systematically collected and analyzed OCP concentrations in Ethiopian water, sediment, and biota, including fish and water birds. Additionally, we calculated the bioaccumulation factor (BAF) and biota-sediment accumulation factor (BSAF) and assessed the human health risks associated with OCP exposure. As such, the outputs of this study will contribute to filling the existing knowledge gap and can be used to inform policy decisions and develop mitigation measures towards OCP concerns in Ethiopia and in other developing countries with similar settings and practices.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Data collection and processing

To identify relevant studies on organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in Ethiopian waters, we conducted a comprehensive systematic search in the PubMed and Scopus databases. The search terms used were “Organochlorine pesticides, OCPs, Chlorinated hydrocarbons, Persistent organic pollutants, chlorinated pesticides,” combined with “Surface water, Sediment, Biota.” Additionally, we utilized the Publish or Perish software (https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish) to search Google Scholar and obtain the top 1000 results. Reference scanning was also employed to identify additional relevant studies. The search was limited to Ethiopia without any restrictions on the year of study (see Asefa et al. [6] for details). In total, 980 studies were retrieved and screened based on title, abstract, and full texts for inclusion in this study. Studies were included if they reported concentrations of any OCP compounds or metabolites in Ethiopian water resources. Studies focusing on pesticides other than OCPs, developed and validated analytical methods for OCP monitoring, or non-original review articles were excluded. Finally, 24 peer-reviewed studies were included to derive the dataset of OCP concentrations used for analysis in this study (Supplementary Material (SM) Table S1).

From the included studies, we extracted information on the reported OCP compounds or metabolites and their concentrations separately for the water phase, sediments, and biota, whenever available. Additionally, supplementary data such as sampling location, water body type, sampling year, and limit of detection/quantification (LOD/LOQ) were also incorporated, if provided. To ensure the quality of the OCP concentrations used in our analysis, we critically assessed the methodological rigor, appropriateness of sampling methods, sample handling procedures, reliability of analytical tools, and adherence to good laboratory practices for each of the included studies (Table S1; also see Asefa et al. [6] for details). Importantly, we only included OCP concentrations that were detected and quantified. In cases where OCPs were detected but not quantified (n=6), we cautiously included them by converting them to half of the LOD when applicable [18], [75]. The studies reporting OCP concentrations in Ethiopian water resources were mapped using QGIS (https://qgis.org/en/site/), utilizing the sample locations and related information provided in the included studies.

2.2. Meta-analysis

We conducted an analysis of three separate yet interrelated water matrices: the water phase, sediment phase, and biota (fish and water birds). The analysis encompassed 30 OCP compounds and metabolites, with approximately 398 reported concentrations within these matrices in Ethiopian waters. For each matrix, summary statistics including the frequency of occurrence, mean, maximum, and 90th percentile concentrations of the OCPs were calculated. The pollution source ascertainment for the commonly detected DDTs and HCHs was calculated using parent/metabolite ratios. For DDTs, the ratio of p,p′-DDT/(p,p′-DDE + p,p′-DDD) was used, while for HCHs, the ratio of β/α + γ-HCH was utilized. A ratio greater than 1 suggests recent use, while a value lower than 1 indicates historical usage [26], [67]. Furthermore, the α/γ-HCH ratio was used to differentiate whether the sources of HCH metabolites are from lindane or technical HCHs. A ratio greater than 1 indicates the use of a technical mixture of HCHs, while a value lower than 1 corresponds to the recent utilization of lindane [67].

2.3. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of OCPs in Ethiopian water

To evaluate the accumulation of OCPs and determine the relative contribution of water and sediments as contamination sources in Ethiopian waters, we calculated the bioaccumulation factor (BAF) and the biota sediment accumulation factor (BSAF). BAF is a measure used to quantify the extent to which a chemical substance accumulates in living organisms relative to its concentration in the surrounding water (Eq. 1). On the other hand, BSAF, is the ratio of a chemical substance in living organisms compared to its concentration in the sediment (Eq. 2). Thus, higher BAF and BSAF values indicate a greater potential for bioaccumulation ([34], [74], [82]).

| (1) |

where BAF is bioaccumulation factor (L/kg), Cf = OCPs concentration in fish (µg/kg) and Cw = OCPs water concentration (µg/L)

| (2) |

where BSAF is biota-sediment accumulation factor (µg/kg), Cf = OCPs concentration in fish (µg/kg) and Cs = OCPs sediment concentration (µg/kg).

2.4. Health Risk assessment

To assess the health risks associated with OCPs among the general population (adults weighing 70 kg) in Ethiopia, non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks were evaluated. The assessment focused on dietary exposure to DDTs through drinking water and fish consumption, using risk assessment models provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency [78]. DDT was chosen for evaluation due to its high frequency of detection and its potential for biomagnification in Ethiopian waters. The chronic daily intake (CDI) of DDT (in mg/kg/day) was determined by considering the mean and maximum concentrations, as shown in Eq. 3.

| (3) |

where Cwater or fish is the concentration of DDTs in water (µg/L) or fish (µg/kg); IngR is ingestion rate (2 L/day for water or 0.027 kg/day for fish; EF is exposure frequency (365 days/year); ED is exposure duration for carcinogenic risk (70 years) and non-carcinogenic risk (30 years); BW is average of body weight (70 kg); AT is average time for carcinogenic risk (70 years × 365 days/year) and non-carcinogenic risk (30 years × 365 days/year).

Non-carcinogenic health risks were assessed using the hazard index (HI), which is obtained by dividing the CDI by the reference dose (RfD) (Eq. 4). Carcinogenic health risks, or cancer risks (CR), were evaluated by multiplying the CDI by the cancer slope factor (CSF) (Eq. 5).

| (4) |

where CDI is the chronic daily intake of DDTs; RfD (µg/kg/day) is the maximum allowable dose per day of the DDTs causing non-carcinogenic health effect.

| (5) |

where CDI is the chronic daily intake of DDTs (µg/kg/day), and CSF (µg/kg/day) is the cancer slope factor for DDTs.

The RfD for DDT (0.5 µg/kg/day) and CSF (350 µg/kg/day) were obtained from the USEPA's integrated risk information system [79]. In addition, hypothetical values for water consumption of 2 L/day and fish consumption of 0.027 kg/day for Ethiopians were utilized, as per US EPA [76] and FAO [19], respectively. Acceptable values for non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks were considered to be HI less than 1 and CR within the range of 10−6 to 10−4, respectively [78]. All statistical computations and graphical illustrations were carried out utilizing the open-source software package R (version 4.3.0: https://cran.r-project.org).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. OCPs in Ethiopian water

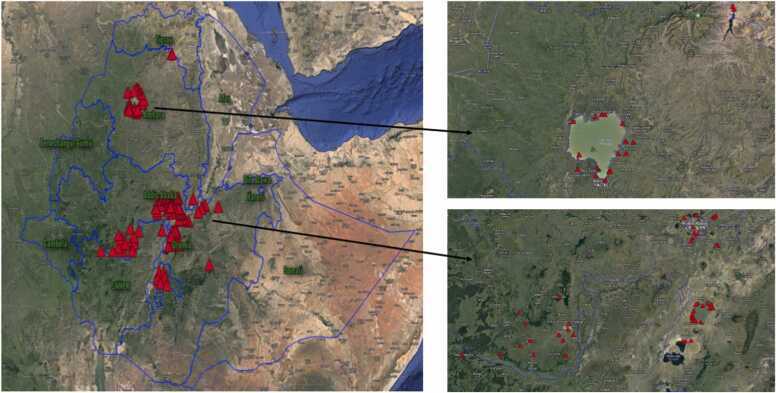

The studies included in our analysis yielded a comprehensive dataset comprising approximately 398 concentrations for 30 OCP compounds and their metabolites across different matrices, including water (n=115), sediment (n=88), and biota (n=195). Notably, among the 24 studies included, 17 focused specifically on the Rift Valley (RV) region of Ethiopia, accounting for about 82 % of the total dataset (Fig. 1 and Table S1). Similar studies conducted in Ethiopia and elsewhere also reported such a geographical bias [50], [56], [6], [66]. The concentration of studies in the RV region can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the region has a long history of extensive OCP use, which has likely resulted in higher levels of contamination and environmental impact. Secondly, the illegal utilization of these pesticides is prevalent in the area [4], [44], [45]. Additionally, the region is proximate to research institutions and advanced laboratories, contributing to the increased research interest in the area.

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of OCP studies in Ethiopian water resources.

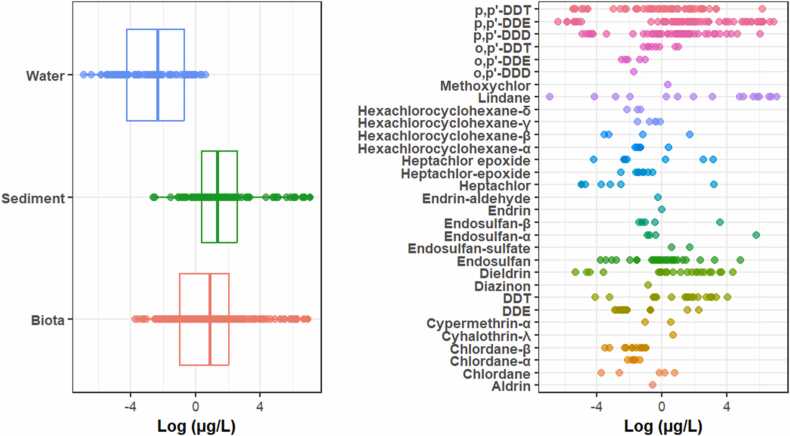

The detection of OCPs across the three matrices analyzed varied. Most detections were reported in sediments (n=26) and biota (n=23), with water (n=15) having the lowest number of detections (Table S2). The overall OCP concentrations in water resources in Ethiopia ranged from 0.001 to 1161.2 µg/L, with a mean concentration of 33.77 µg/L (Fig. 2). The higher concentrations were reported in sediments (90th percentile = 153.015 µg/kg), followed by biota (90th percentile = 55.2 µg/kg) and water (90th percentile = 0.89 µg/L) (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

OCP concentrations among the three water matrices in Ethiopia, water (n=115), sediment (n=88), and biota (n=195).

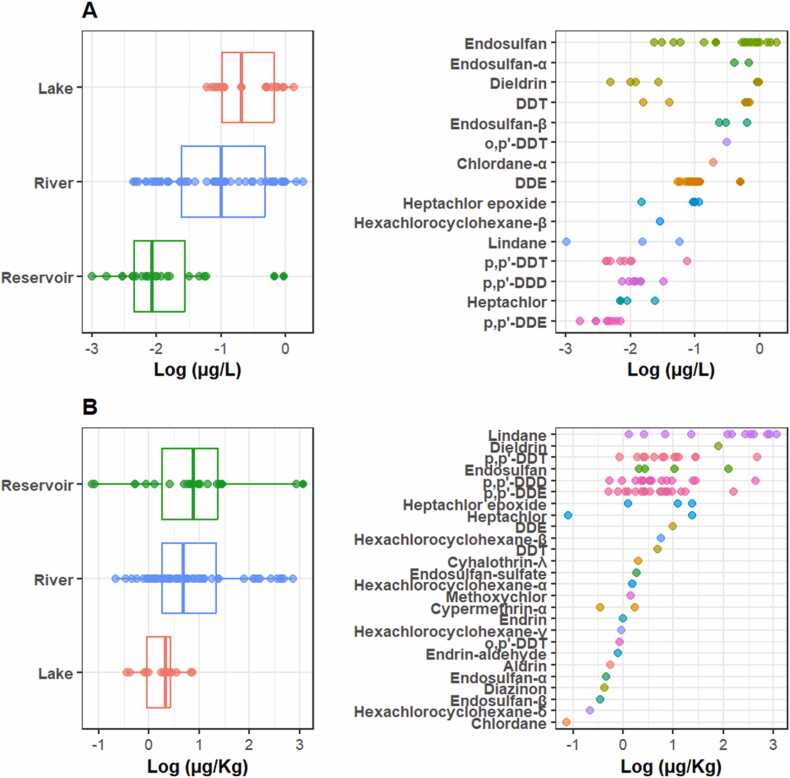

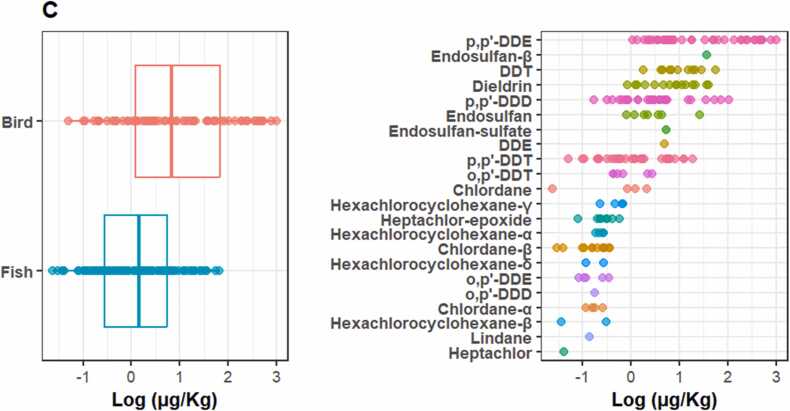

Furthermore, the detection of OCPs among the subcategories within each matrix also varied. Water in reservoirs was found to be less polluted by OCPs compared to rivers and lakes, while the sediment in lakes was less polluted compared to rivers and reservoirs. However, in both cases, it was found that river water resources are highly exposed to OCPs, indicating that they are more vulnerable ecosystems in Ethiopia (Fig. 3). Studies also reported that rivers are more exposed to pesticides, although the extent depends on factors such as surrounding land use and water flow patterns [27], [37], [80]. Moreover, the biota subcategory included a total of seven fish species and four bird species, of which fish had the highest number of reported OCPs (about 66 %) compared to birds. However, high OCP concentrations were reported in birds (Fig. 4). In this regard, significant variations among the species analyzed were also observed, in agreement with other studies [23], [24], [56].

Fig. 3.

OCP concentrations in A (water; n=115) and B (sediments; n=88) and their subcategories in water resources in Ethiopia.

Fig. 4.

OCP concentrations in C (biota; n=195) and its subcategories in water resources in Ethiopia.

Among the OCPs analyzed, DDTs, endosulfan, and HCHs were the most frequently detected in Ethiopian waters, with p,p′-DDE (n=70) being the most commonly found compound across all three matrices examined (Fig. 2). The overall highest reported concentrations of OCPs were 1161.2 µg/kg in sediments and 1003 µg/kg in birds, corresponding to lindane and the DDT metabolite p,p′-DDE, respectively (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Similar studies conducted elsewhere also showed a similar pattern [54], [55], [56], [61], [62], [67].

The mean concentrations of DDTs ranged from 0.002 to 1003 µg/L, with an average concentration of 34.588 µg/L and high detections in birds and fish (Fig. 4). Source ascertainment indicated that DDTs in Ethiopian waters were less dominated by the parental metabolites, indicating historical inputs in contrast to the results of the study conducted in India [62]. The overall occurrence of DDT metabolites in Ethiopian waters followed the order of p,p′-DDE > p,p′-DDD > p,p′-DDT > o,p′-DDT > o,p′-DDE > o,p′-DDD (Table S2). The higher detection of p,p′-DDE in this study could be attributed to the biological persistence of this metabolite compared to other DDT compounds [24], [30], [84].

Endosulfan, another frequently detected OCP, exhibited an overall concentration ranging from 0.023 to 341.5 µg/L, with a mean concentration of 13.297 µg/L (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The mean concentrations of endosulfan were in the order of α-endosulfan > β-endosulfan > endosulfan sulfate (Table S2). The concentrations of HCHs ranged from 0.029 to 5.68 µg/L, with an average concentration of 0.686 µg/L and high detections in sediments and fish (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). No HCHs were reported in water samples. The order of HCH isomers was HCH-β > HCH-α > HCH-γ > HCH-δ (Table S2). Source ascertainment indicated recent usage of HCHs in the surrounding areas, probably from the use of lindane. Similar results have also been reported in other studies [61], [62], [67], [81].

Overall, the findings indicate higher concentrations of OCPs across different matrices in Ethiopian waters. However, there is significant variation in the distribution and concentrations of OCPs in these matrices and their subcategories. This can likely be attributed to several factors, including the physicochemical properties of the compounds, their persistence in the environment, and the specific characteristics of the matrices [10], [20], [28], [29], [57], [9]. The concentration of p,p′-DDE in birds was found to be up to 57 and 143,286 times higher than the concentrations in sediment and water, respectively, clearly demonstrating the biomagnification of DDTs in the food chain of the Ethiopian aquatic ecosystem. Importantly, when comparing the levels of OCPs with currently used pesticides (CUPs) in Ethiopia, as presented in Asefa et al. [6], the levels of OCPs reported in this study were found to be eight times higher. This demonstrates the continued presence and concern of OCPs in Ethiopia and their significance compared to CUPs. Similar conclusions have also been drawn in studies conducted in other tropical environments [11], [12], [32], [52], [53], [54], [55], [64], [83].

3.2. BAF and BSAF of OCPs in Ethiopian water

The highest bioaccumulation factor (BAF) values were observed for p,p′-DDE, endosulfan-α, p,p′-DDT, and p,p′-DDD, indicating their significant tendency to bioaccumulate in biota compared to their concentration in water (Table S2). Conversely, some OCPs, such as lindane, heptachlor, and chlordane-α, showed lower BAF values, indicating relatively lower bioaccumulation potential. Regarding the bioaccumulation from sediments, the highest values of the BSAF were observed for endosulfan-α, endosulfan-β, and chlordane, indicating their significant ability to accumulate in fish originating from sediments (Table S2). In contrast, lower BSAF values were observed for DDT metabolites, suggesting that the main source of fish contamination is through bioconcentration and bioaccumulation directly from the surrounding water, rather than from sediments. In line with these findings, field studies conducted in Ethiopia have shown that OCPs, especially DDT metabolites, biomagnified across aquatic food webs with increasing trophic levels [15], [46], [7], [87].

However, it is important to interpret these results with caution, as our study found higher concentrations of DDTs in biota, particularly in fish consuming birds, indicating the biomagnification of DDTs in Ethiopian waters (see Section 3.1). Therefore, the bioaccumulation of OCPs in fish in Ethiopia may not be solely attributed to direct uptake from the surrounding environment but also to uptake through the food chain and food web, which play an important role in the Ethiopian aquatic ecosystem. While some studies have suggested that direct uptake of compounds from water does not significantly contribute to the total contaminant concentration in organisms [34], [82], our study found the opposite result, with bioaccumulation of OCPs better represented by BAF (mean: 264) than BSAF (mean: 48.3). This difference could be attributed to various factors, including the characteristics of tropical waters, fish behavior, sediment characteristics, and properties of OCPs [59]. However, to gain a better understanding of the fate of these pesticide compounds in Ethiopian waters, differences in trophic levels, annual exposure and absorption, and annual net retention among different fish species should be considered.

3.3. Human health risks assessment

We found that the general population in Ethiopia is exposed to higher health risks associated with dietary intake of DDTs through fish consumption rather than through drinking water. The overall non-carcinogenic risks in the water were within acceptable limits for drinking, with mean concentrations ranging from 9.34E-03–3.59E-01 and maximum concentrations ranging from 4.00E-02–2.86E-02 (Table 1). In addition, no cancer risks associated with DDT exposure through drinking water in Ethiopia were observed. However, it is important to note that if the drinking water source is a river, the risks may be higher, especially with long-term exposure or higher consumption rates due to its higher DDT concentrations, which could lead to health effects.

Table 1.

Non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks associated with dietary intake of DDTs through drinking water and fish consumption among the general Ethiopian population. Risks were calculated for the mean and maximum concentrations reported, and values exceeding safe levels are indicated in bold font.

| Dietary consumption | Concentration Mean | ADI | Non-Carcinogenic | Carcinogenic | Concentration Maximum | ADI | Non-Carcinogenic | Carcinogenic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking Water | 0.14 | 0.00 | 7.93E-03 | 1.13E-05 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 4.00E-02 | 5.71E-05 |

| Lake | 0.21 | 0.01 | 1.18E-02 | 1.69E-05 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 2.86E-02 | 4.08E-05 |

| Reservoir | 0.05 | 0.00 | 2.76E-03 | 3.94E-06 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 3.83E-02 | 5.47E-05 |

| River | 0.16 | 0.00 | 9.34E-03 | 1.33E-05 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 4.00E-02 | 5.71E-05 |

| Fish | 6.29 | 0.18 | 3.59E-01 | 5.13E-04 | 56.00 | 1.60 | 3.20E+00 | 4.57E-03 |

| Barbus intermedius | 22.61 | 0.65 | 1.29E+00 | 1.85E-03 | 56.00 | 1.60 | 3.20E+00 | 4.57E-03 |

| Carassius auratus | 4.91 | 0.14 | 2.80E-01 | 4.01E-04 | 12.49 | 0.36 | 7.14E-01 | 1.02E-03 |

| Clarias gariepinus | 8.13 | 0.23 | 4.64E-01 | 6.63E-04 | 33.69 | 0.96 | 1.93E+00 | 2.75E-03 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 6.04 | 0.17 | 3.45E-01 | 4.93E-04 | - | - | - | - |

| Oreochromis niloticus | 4.28 | 0.12 | 2.44E-01 | 3.49E-04 | 19.16 | 0.55 | 1.09E+00 | 1.56E-03 |

| Tilapia zilli | 1.77 | 0.05 | 1.01E-01 | 1.45E-04 | 4.71 | 0.13 | 2.69E-01 | 3.84E-04 |

On the other hand, the risks associated with DDT exposure through fish consumption were found to be unacceptable. The overall non-carcinogenic risks ranged from 3.59E-01–3.20E+00, and the cancer risks ranged from 5.13E-04–4.57E-03 (Table 1). Specifically, consuming Barbus intermedius, Clarias gariepinus, and Oreochromis niloticus posed both non-carcinogenic and cancer risks, while Carassius auratus posed cancer risks among the general population in Ethiopia (Table 1). It is important to note that these fish species are commercially important in Ethiopia and commonly consumed across the country [2], although the consumption rate varies [16], [69]. Therefore, individuals who consume fish more frequently and prefer to consume various species will have a higher intake of DDTs, thus increasing the associated risks.

DDT and its metabolites may act as endocrine disruptors and have carcinogenic properties. They are associated with adverse health outcomes such as breast cancer, diabetes, abortion, and cognitive impairment [17], [68]. In line with the findings of our study, biomonitoring studies conducted in Ethiopia have also reported higher concentrations of DDT metabolites, i.e., p,p′-DDT and p,p′-DDE, in human serum [1], [41]. Furthermore, the epidemiological study by Mekonen et al. [42] suggested that OCPs are risk factors for breast cancer. The study found that a one-unit increase in p,p′-DDT concentration doubled the odds of developing breast cancer (AOR: 2.03, 95 % CI: 1.041–3.969) [42]. In this regard, although the majority of studies in Ethiopia have focused on the occupational aspects of pesticide exposure, associated adverse effects such as respiratory health problems and neurobehavioral symptoms have also been reported in the country [43], [48], [49]. However, further research is needed to comprehensively investigate OCP exposure and adverse effects through all direct and indirect pathways, focusing on environmental exposures. Moreover, strict OCP regulations are urgently required to protect human health in Ethiopia.

3.4. Result implications and conclusion

This study presents the first comprehensive analysis of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in aquatic ecosystems in Ethiopia. The study examines various aspects, including bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and potential health risks associated with dietary exposure to OCPs. The need for this study arises from several knowledge gaps that exist in developing countries regarding the impact of legacy pesticides. Despite the prohibition of OCPs in many countries, their use continues in developing countries including Ethiopia, posing a significant threat to biodiversity [31], [54], [71], [8]. However, there is limited evidence regarding the extent of contamination and the resulting consequences for human and environmental health risks in Ethiopia. To address these gaps, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of three interrelated water matrices (water phase, sediment phase, and biota) in Ethiopia, using 30 OCP compounds and metabolites, totaling approximately 398 concentrations.

Our findings revealed high concentrations of OCPs in Ethiopian waters. However, there is significant variation among the matrices and their subcategories analyzed. Importantly, about 82 % of the OCP concentrations included in this study were in the Rift Valley (RV) region of the country, indicating an uneven spatial distribution of OCPs. Additionally, insufficient temporal OCP data limited the detailed analysis of changes in OCP concentrations before and after the implementation of bans in Ethiopia. Thus, we were unable to conduct a detailed spatial and temporal analysis of OCPs in Ethiopian waters. However, despite the need for additional monitoring efforts, the analysis of OCP concentrations presented in this study provides valuable insights into the existing contamination status of Ethiopian water matrices concerning legacy pesticides. We found that OCPs are more concerning than current-use pesticides (CUPs) in terms of their concentrations and associated risks. Evidence of bioaccumulation and biomagnification was also found in this study. Overall, our findings were consistent with similar studies conducted elsewhere [11], [12], [32], [52], [53], [54], [55], [64], [83].

Although the exact sources of OCPs in Ethiopian waters were not reported in the included studies, previous research has identified non-point agricultural sources and vector-borne controls as primary sources. In Ethiopia, until very recently, OCPs such as DDT and endosulfan were locally manufactured by Adami Tulu Pesticide Processing Share Company. Despite some recent efforts made by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) and Ministry of Health (MoH) to dispose DDT and ban and restriction of the use of DDT and Endosulfan; Debela et al.[13] showed that hundreds and thousands of DDT are stored in the company's warehouse, and there are approximately 460 sites suspected to be contaminated with DDT. Furthermore, stockpiles of obsolete pesticides are widely spread throughout the entire country, which can be an important source of contamination in Ethiopian water [14], [25], [38]. Therefore, although our findings showed the historical use of DDT in Ethiopia, the recent input from the ongoing illegal use of OCPs, as well as leaching from obsolete pesticide stocks, could explain the high concentrations reported in this study.

Although this study did not observe any health risks associated with DDT exposure through drinking water, we did identify a significant health risk concern for the general Ethiopian population related to fish consumption, with varying risks depending on the fish species consumed. It is important to note that this study focused on DDT as a representative OCP compound for health risk assessment and did not consider the cumulative effects of multiple OCP exposures, although these approaches are highly recommended for risk assessments [51], [77]. Furthermore, the assessment assumed hypothetical exposure scenarios and did not account for potential hotspots or localized areas with higher contamination levels. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution and considered as a preliminary assessment of the potential health risks associated with OCP exposure in Ethiopia until further studies explore the risks in more detail.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate ongoing concerns regarding OCPs in various water matrices in Ethiopia, as evidenced by their high concentrations, ability to bioaccumulate and biomagnify, and the health risks posed through dietary exposures. However, due to the scarcity of data and significant heterogeneity among the matrices analyzed, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions about the spatiotemporal trends of OCPs in Ethiopia. These findings emphasize the need for ongoing monitoring and assessment of OCP contamination in Ethiopian waters, with particular attention to understanding the dynamics across varying space and time domains. Furthermore, given the continued concerns regarding OCPs, it is crucial to re-evaluate regulations on their use and promote sustainable agricultural and environmental management practices to mitigate the release of these compounds.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Roba Argaw Tessema: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Jerry Enoe: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Józef Ober: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Berhan M. Teklu: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Ermias Deribe Woldemariam: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. Elsai Mati Asefa: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mekuria Teshome Mergia: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Yohannes Tefera Damtew: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Dechasa Adare Mengistu: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Faye Fekede Dugusa: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Prof. L.H. Lash

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2024.06.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Afata T.N., Mekonen S., Tucho G.T. Evaluating the level of pesticides in the blood of small-scale farmers and its associated risk factors in Western Ethiopia. Environ. Health Insights. 2021;Vol. 15 doi: 10.1177/11786302211043660. 117863022110436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agumassie T. Breeding seasons of some commercially important fishes in Ethiopia: Implications for fish management. Sci. Res. Essays. 2019;Vol. 14(No. 2):9–14. doi: 10.5897/SRE2018.6596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhtar N., Syakir Ishak M.I., Bhawani S.A., Umar K. Various natural and anthropogenic factors responsible for water quality degradation: a review. Water. 2021;Vol. 13(No. 19):2660. doi: 10.3390/w13192660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali S.A., Destaye A.G. Apparent Khat chewers exposure to DDT in Ethiopia and its potential toxic effects: a scoping review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2023.105555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anju A., Ravi S., P., Bechan S., Agrawal A., Pandey R.S., Sharma B. Vol. 2010. Scientific Research Publishing; 2010. Water Pollution with Special Reference to Pesticide Contamination in India. (Journal of Water Resource and Protection). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asefa E.M., Mergia M.T., Ayele S., Damtew Y.T., Teklu B.M., Weldemariam E.D. Pesticides in Ethiopian surface waters: a meta-analytic based ecological risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024;Vol. 911 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayele S., Mamo Y., Deribe E., Eklo O.M. Levels of organochlorine pesticides in five species of fish from Lake Ziway, Ethiopia. Sci. Afr. 2022;Vol. 16 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2022.e01252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biscoe M.L., Mutero C.M., Kramer R.A. Vol. 95. IWMI; 2004. (Current Policy and Status of DDT Use for Malaria Control in Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya and South Africa). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao X., Lu R., Xu Q., Zheng X., Zeng Y., Mai B. Distinct biomagnification of chlorinated persistent organic pollutants in adjacent aquatic and terrestrial food webs. Environ. Pollut. 2023;Vol. 317 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra A.K., Sharma M.K., Chamoli S. Bioaccumulation of organochlorine pesticides in aquatic system—an overview. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011;Vol. 173(No. 1–4):905–916. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daam M.A., Van den Brink P.J. Implications of differences between temperate and tropical freshwater ecosystems for the ecological risk assessment of pesticides. Ecotoxicology. 2010;Vol. 19(No. 1):24–37. doi: 10.1007/s10646-009-0402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daam M.A., Chelinho S., Niemeyer J.C., Owojori O.J., De Silva P.M.C.S., Sousa J.P., van Gestel C.A.M., et al. Vol. 181. Elsevier; 2019. Environmental risk assessment of pesticides in tropical terrestrial ecosystems: Test procedures, current status and future perspectives; pp. 534–547. (Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Debela S.A., Sheriff I., Daba C., Tefera Y.M., Bedada D., Gebrehiwot M. Status of persistent organic pollutants in Ethiopia. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023;Vol. 11 doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1182048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debela S.A., Wu J., Chen X., Zhang Y. Stock status, urban public perception, and health risk assessment of obsolete pesticide in Northern Ethiopia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;Vol. 27(No. 21):25837–25847. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deribe E., Rosseland B.O., Borgstrøm R., Salbu B., Gebremariam Z., Dadebo E., Norli H.R., et al. Vol. 410. Elsevier; 2011. Bioaccumulation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in fish species from Lake Koka, Ethiopia: the influence of lipid content and trophic position; pp. 136–145. (Science of the Total Environment). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deribe E., Rosseland B.O., Borgstrøm R., Salbu B., Gebremariam Z., Dadebo E., Skipperud L., et al. Vol. 93. Springer; 2014. Organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in fish from Lake Awassa in the Ethiopian rift valley: Human health risks; pp. 238–244. (Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eskenazi B., Chevrier J., Rosas L.G., Anderson H.A., Bomman M.S., Bouwman H., Chen A., et al. The pine river statement: Human health consequences of DDT use. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;Vol. 117(No. 9):1359–1367. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.EU “Common Implementation Strategy for the Water. Framew. Dir. ”, Framew. 2000;Vol. 428(No. 24):28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.FAO “Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles: Ethiopia”, Country Profile Fact Sheets : FAO Fish. Div. [Online] 2014:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Femina C., Kamalesh T., Senthil Kumar P., Rangasamy G. An insights of organochlorine pesticides categories, properties, eco-toxicity and new developments in bioremediation process. Environ. Pollut. 2023;Vol. 333 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuhrimann, S., Wan, C., Blouzard, E., Veludo, A. and … (2021), “Pesticide research on environmental and human exposure and risks in sub-saharan africa: A systematic literature review”, … of Environmental …. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Gentil C., Fantke P., Mottes C., Basset-Mens C. Challenges and ways forward in pesticide emission and toxicity characterization modeling for tropical conditions. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020;Vol. 25(No. 7):1290–1306. doi: 10.1007/s11367-019-01685-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girones L., Oliva A.L., Marcovecchio J.E., Arias A.H. Spatial Distribution and Ecological Risk Assessment of Residual Organochlorine Pesticides (OCPs) in South American Marine Environments. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020;Vol. 7(No. 2):147–160. doi: 10.1007/s40572-020-00272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grung M., Lin Y., Zhang H., Steen A.O., Huang J., Zhang G., Larssen T. Vol. 81. Elsevier; 2015. Pesticide levels and environmental risk in aquatic environments in China - A review; pp. 87–97. (Environment International). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haylamicheal I.D., Dalvie M.A. Disposal of obsolete pesticides, the case of Ethiopia. Environ. Int. 2009;Vol. 35(No. 3):667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He W., Qin N., He Q.-S., Wang Y., Kong X.-Z., Xu F.-L. Characterization, ecological and health risks of DDTs and HCHs in water from a large shallow Chinese lake. Ecol. Inform. 2012;Vol. 12:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrmann L.Z., Bub S., Wolfram J., Stehle S., Petschick L.L., Schulz R. Large monitoring datasets reveal high probabilities for intermittent occurrences of pesticides in European running waters. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023;Vol. 35(No. 1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12302-023-00795-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiranmai R.Y., Kamaraj M. Occurrence, fate, and toxicity of emerging contaminants in a diverse ecosystem. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2023;Vol. 8(No. 9):2219–2242. doi: 10.1515/psr-2021-0054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jayaraj R., Megha P., Sreedev P. Review Article. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2016;Vol. 9(No. 3–4):90–100. doi: 10.1515/intox-2016-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jürgens M.D., Crosse J., Hamilton P.B., Johnson A.C., Jones K.C. The long shadow of our chemical past – High DDT concentrations in fish near a former agrochemicals factory in England. Chemosphere. 2016;Vol. 162:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keswani C., Dilnashin H., Birla H., Roy P., Tyagi R.K., Singh D., Rajput V.D., et al. Global footprints of organochlorine pesticides: a pan-global survey. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2022;Vol. 44(No. 1):149–177. doi: 10.1007/s10653-021-00946-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kidd K.A., Bootsma H.A., Hesslein R.H., Muir D.C.G., Hecky R.E. Biomagnification of DDT through the benthic and pelagic food webs of Lake Malawi, East Africa: Importance of trophic level and carbon source. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001;Vol. 35(No. 1):14–20. doi: 10.1021/es001119a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiyani R., Dehdashti B., Heidari Z., Sharafi S.M., Mahmoodzadeh M., Amin M.M. Biomonitoring of organochlorine pesticides and cancer survival: a population-based study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023;Vol. 30(No. 13):37357–37369. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24855-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwok C.K., Liang Y., Leung S.Y., Wang H., Dong Y.H., Young L., Giesy J.P., et al. Biota–sediment accumulation factor (BSAF), bioaccumulation factor (BAF), and contaminant levels in prey fish to indicate the extent of PAHs and OCPs contamination in eggs of waterbirds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013;Vol. 20(No. 12):8425–8434. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-1809-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis-Mikhael A.M., Olmedo-Requena R., Martínez-Ruiz V., Bueno-Cavanillas A., Jiménez-Moleón J.J. Organochlorine pesticides and prostate cancer, Is there an association? A meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;Vol. 26(No. 10):1375–1392. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0643-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis S.E., Silburn D.M., Kookana R.S., Shaw M. Pesticide Behavior, Fate, and Effects in the Tropics: An Overview of the Current State of Knowledge. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;Vol. 64(No. 20):3917–3924. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lima-Junior D.P., Lima L.B., Carnicer C., Zanella R., Prestes O.D., Floriano L., De Marco Júnior P. Exploring the relationship between land-use and pesticides in freshwater ecosystem: A case study of the Araguaia River Basin, Brazil. Environ. Adv. 2024;Vol. 15 doi: 10.1016/j.envadv.2024.100497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loha K.M., Lamoree M., Weiss J.M., de Boer J. Import, disposal, and health impacts of pesticides in the East Africa Rift(EAR) zone: A review on management and policy analysis. Crop Prot. 2018;Vol. 112:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2018.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo D., Zhou T., Tao Y., Feng Y., Shen X., Mei S. Exposure to organochlorine pesticides and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 2016;Vol. 6(No. 1) doi: 10.1038/srep25768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martyniuk C.J., Mehinto A.C., Denslow N.D. Organochlorine pesticides: Agrochemicals with potent endocrine-disrupting properties in fish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020;Vol. 507 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mekonen S., Belete B., Melak F., Ambelu A. Determination of pesticide residues in the serum of flower farm workers: A growing occupational hazards in low income countries. Toxicol. Rep. 2023;Vol. 10:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mekonen S., Ibrahim M., Astatkie H., Abreha A. Exposure to organochlorine pesticides as a predictor to breast cancer: A case-control study among Ethiopian women. Singh S.P., editor. PLoS ONE. 2021;Vol. 16(No. 9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257704. (September) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mekonnen Y., Agonafir T. Effects of pesticide applications on respiratory health of Ethiopian farm workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health. 2002;Vol. 8(No. 1):35–40. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2002.8.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mengistie B. Policy-Practice Nexus: Pesticide Registration, Distribution and use in Ethiopia. SM J. Environ. Toxicol. 2016;Vol. 2(No. ii):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mengistie B.T., Mol A.P.J., Oosterveer P. Pesticide use practices among smallholder vegetable farmers in Ethiopian Central Rift Valley. Environ., Dev. Sustain. 2017;Vol. 19(No. 1):301–324. doi: 10.1007/s10668-015-9728-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mergia M.T., Weldemariam E.D., Eklo O.M., Yimer G.T. Vol. 108. Springer; 2022. Levels and Trophic Transfer of Selected Pesticides in the Lake Ziway Ecosystem; pp. 830–838. (Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Negatu B., Kromhout H., Mekonnen Y., Vermeulen R. Vol. 60. Oxford University Press; 2016. Use of chemical pesticides in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional comparative study Onknowledge, attitude and practice of farmers and farm workers in three farming systems”; pp. 551–566. (The Annals of Occupational Hygiene). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Negatu B., Kromhout H., Mekonnen Y., Vermeulen R. Occupational pesticide exposure and respiratory health: A large-scale cross-sectional study in three commercial farming systems in Ethiopia. Thorax. 2017;Vol. 72(No. 6):522–529. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Negatu B., Vermeulen R., Mekonnen Y., Kromhout H. Neurobehavioural symptoms and acute pesticide poisoning: A cross-sectional study among male pesticide applicators selected from three commercial farming systems in Ethiopia. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018;Vol. 75(No. 4):283–289. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2017-104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowicki S., Birhanu B., Tanui F., Sule M.N., Charles K., Olago D., Kebede S. Water chemistry poses health risks as reliance on groundwater increases: A systematic review of hydrogeochemistry research from Ethiopia and Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;Vol. 904 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.OECD Considerations for Assessing the Risks of Combined Exposure to Multiple Chemicals”. Ser. Test. Assess. 2018;(No. 296):119. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olisah C., Adeola A.O., Iwuozor K.O., Akopmie K.G., Conradie J., Adegoke K.A., Oyedotun K.O., et al. Chemosphere. Elsevier; 2022. A bibliometric analysis of pre-and post-Stockholm Convention research publications on the Dirty Dozen Chemicals (DDCs) in the African environment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olisah C., Okoh O.O., Okoh A.I. Global evolution of organochlorine pesticides research in biological and environmental matrices from 1992 to 2018: A bibliometric approach. Emerg. Contam. 2019;Vol. 5:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2019.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olisah C., Okoh O.O., Okoh A.I. Vol. 6. Elsevier; 2020. Occurrence of organochlorine pesticide residues in biological and environmental matrices in Africa: A two-decade review. (Heliyon). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oliveira A.H.B., Cavalcante R.M., Duaví W.C., Fernandes G.M., Nascimento R.F., Queiroz M.E.L.R., Mendonça K.V. The legacy of organochlorine pesticide usage in a tropical semi-arid region (Jaguaribe River, Ceará, Brazil): Implications of the influence of sediment parameters on occurrence, distribution and fate. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;Vol. 542:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Padayachee K., Reynolds C., Mateo R., Amar A. A global review of the temporal and spatial patterns of DDT and dieldrin monitoring in raptors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;Vol. 858 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Potapowicz J., Lambropoulou D., Nannou C., Kozioł K., Polkowska Ż. “Occurrences, sources, and transport of organochlorine pesticides in the aquatic environment of Antarctica”. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;Vol. 735 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qi S.Y., Xu X.L., Ma W.Z., Deng S.L., Lian Z.X., Yu K. Effects of Organochlorine Pesticide Residues in Maternal Body on Infants. Front. Endocrinol. 2022;Vol. 13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.890307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu Y.W., Qiu H.L., Zhang G., Li J. Bioaccumulation and cycling of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in three mangrove reserves of south China. Chemosphere. 2019;Vol. 217:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardson S.D., Kimura S.Y. Vol. 8. Elsevier; 2017. Emerging environmental contaminants: Challenges facing our next generation and potential engineering solutions; pp. 40–56. (Environmental Technology and Innovation). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saadati N., Abdullah M.P., Zakaria Z., Rezayi M., Hosseinizare N. Distribution and fate of HCH isomers and DDT metabolites in a tropical environment–case study Cameron Highlands–Malaysia. Chem. Cent. J. 2012;Vol. 6(No. 1):130. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarkar S.K., Bhattacharya B.D., Bhattacharya A., Chatterjee M., Alam A., Satpathy K.K., Jonathan M.P. Occurrence, distribution and possible sources of organochlorine pesticide residues in tropical coastal environment of India: An overview. Environ. Int. 2008;Vol. 34(No. 7):1062–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma A., Shukla A., Attri K., Kumar M., Kumar P., Suttee A., Singh G., et al. Global trends in pesticides: A looming threat and viable alternatives. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;Vol. 201 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snyder, J., Smart, J., Goeb, J. and Tschirley, D. (2015), Pesticide Use in Sub-Saharan Africa: Estimates, Projections, and Implications in the Context of Food System Transformation, IIAM Research Report.

- 65.de Souza R.M., Seibert D., Quesada H.B., de Jesus Bassetti F., Fagundes-Klen M.R., Bergamasco R. Occurrence, impacts and general aspects of pesticides in surface water: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020;Vol. 135:22–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2019.12.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stehle S., Schulz R. Agricultural insecticides threaten surface waters at the global scale. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;Vol. 112(No. 18):5750–5755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500232112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sultan M., Hamid N., Junaid M., Duan J.J., Pei D.S. Organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in freshwater resources of Pakistan: a review on occurrence, spatial distribution and associated human health and ecological risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023;Vol. 249 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taiwo A.M. A review of environmental and health effects of organochlorine pesticide residues in Africa. Chemosphere. 2019;Vol. 220:1126–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tamiru M., Alkhtib A., Ahmedsham M., Worku Z., Tadese D.A., Teka T.A., Geda F., et al. Fish consumption and quality by peri-urban households among fish farmers and public servants in Ethiopia. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2023;Vol. 23(No. 3):498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ecohyd.2023.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tavalieri Y.E., Galoppo G.H., Canesini G., Luque E.H., Muñoz-de-Toro M.M. Effects of agricultural pesticides on the reproductive system of aquatic wildlife species, with crocodilians as sentinel species. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020;Vol. 518 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson L.A., Darwish W.S., Ikenaka Y., Nakayama S.M.M., Mizukawa H., Ishizuka M. Vol. 79. Japanese Society of Veterinary Science; 2017. Organochlorine pesticide contamination of foods in Africa: incidence and public health significance; pp. 751–764. (Journal of Veterinary Medical Science). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsygankov V.Y. Organochlorine pesticides in marine ecosystems of the Far Eastern Seas of Russia (2000–2017) Water Res. 2019;Vol. 161:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.05.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tzanetou E.N., Karasali H. A Comprehensive Review of Organochlorine Pesticide Monitoring in Agricultural Soils: The Silent Threat of a Conventional Agricultural Past. Agriculture. 2022;Vol. 12(No. 5):728. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12050728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.U.S. EPA. (2000), “Bioaccumulation testing and interpretation for the purpose of sediment quality assessment status and needs”, No. February, p. 111.

- 75.US EPA. (2000), “Assigning values to non-detected/non-quantified pesticide residues in human health food exposure assessments”, No. 6047, pp. 1–25.

- 76.US EPA. (2014), “Human health evaluation manual, supplemental guidance: ‘Standard default exposure factors’”, Vol. I No. 202.

- 77.US EPA. (2021), “Exposure Assessment Tools by Tiers and Types - Aggregate and Cumulative”.

- 78.US EPA. (2023a), “Human Health Risk Models and Tools | US EPA”, available at: 〈https://www.epa.gov/risk/human-health-risk-models-and-tools〉 (Accessed 22 February 2024).

- 79.US EPA. (2023b), “Integrated Risk Information System US EPA”, Environmental Protection Agency, available at: 〈https://www.epa.gov/iris〉 (Accessed 10 January 2024).

- 80.Vormeier P., Schreiner V.C., Liebmann L., Link M., Schäfer R.B., Schneeweiss A., Weisner O., et al. Temporal scales of pesticide exposure and risks in German small streams. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;Vol. 871 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X., Xu J., Guo C., Zhang Y. Distribution and Sources of Organochlorine Pesticides in Taihu Lake, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012;Vol. 89(No. 6):1235–1239. doi: 10.1007/s00128-012-0854-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weisbrod A.V., Burkhard L.P., Arnot J., Mekenyan O., Howard P.H., Russom C., Boethling R., et al. Workgroup report: review of fish bioaccumulation databases used to identify persistent, bioaccumulative, toxic substances. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;Vol. 115(No. 2):255–261. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weiss F.T., Ruepert C., Echeverría-Sáenz S., Eggen R.I.L., Stamm C. Vol. 11. Elsevier; 2023. Agricultural pesticides pose a continuous ecotoxicological risk to aquatic organisms in a tropical horticulture catchment. (Environmental Advances). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.WHO DDT and its derivatives in drinking-water. World Health Organ. 1989:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu Y., Fan Y., Gao X., Pan X., He H., Zhai J. The association of environmental organochlorine pesticides exposure and human semen parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s10389-023-02007-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xuan Z., Ma Y., Zhang J., Zhu J., Cai M. Dissolved legacy and emerging organochlorine pesticides in the Antarctic marginal seas: Occurrence, sources and transport. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023;Vol. 187 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yohannes Y.B., Ikenaka Y., Nakayama S.M.M., Ishizuka M. Vol. 192. Elsevier; 2014. Organochlorine pesticides in bird species and their prey (fish) from the Ethiopian Rift Valley region, Ethiopia; pp. 121–128. (Environmental Pollution). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.