Health related websites are frequently accessed on the internet. A poll in August 2001 concluded that almost 100 million American adults regularly go on line for information about health care.1 As over 100 000 sites offer health related information, “trying to get information from the internet is like drinking from a fire hose, you don't even know what the source of the water is.”2,3

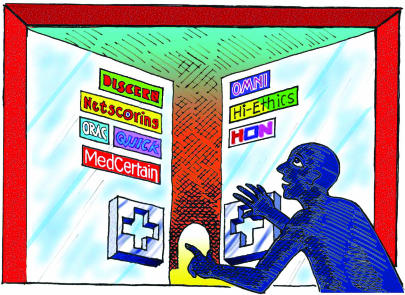

To help users discriminate between sites, a wide range of organisations have developed methods and tools for evaluating and rating the quality of websites. These tools aim to guide the site developers, filter content, and help consumers become discerning users of information.

A range of tools for rating quality exists, and their number has continued to grow since 1996 when the first initiatives produced codes of conduct for health information on the internet.4,5 Some approaches focus on setting ethical standards and promoting the “good” whereas other more pragmatic approaches concentrate on sifting huge amounts of information into manageable chunks. Some approaches address general ethical principles about the nature of health related content whereas others focus on the mode of delivery and the integrity of the use of the web as a medium for the dissemination of information. I describe a classification of five types of approaches for rating the quality of English language websites (table). All start from the basic concept of an agreed set of criteria for good practice in the provision of health related information through websites.

Summary points

Health related websites are among the most widely used websites on the internet

A wide range of tools has been developed to assist site developers to produce good quality sites and for consumers to assess the quality of sites

These tools are classified into five broad categories: codes of conduct, quality labels, user guides, filters, and third party certification

Codes of conduct

Codes of conduct are defined as sets of quality criteria that provide a list of recommendations for the development and content of websites. These codes inform a process of self assessment by providers of websites and educate both providers and consumers of websites about “good” practice so that providers adhere to the codes and consumers grow wary of sites that do not. Several organisations are developing a set of quality criteria for health related websites (box), but the extent to which such codes are implemented varies. Where the code is adopted by an umbrella organisation such as national or specialty based medical associations, the associations ensure that members comply with the code and may discipline members who are not compliant (box). However, some codes have been adopted by a group of individuals whose sole purpose is to draft the code rather than to oversee its implementation (box).

Organisations responsible for codes of conduct

eHealth Code of Ethics of the Internet Health Coalition (www.ihealthcoalition.org/ethics/ethics.html) is one organisation developing a set of quality criteria for health related websites

The American Medical Association (www.ama-assn.org/about/guidelines) oversees the quality of several websites and disciplines providers that do not comply with its criteria

Health Summit Working Group (www.mitretek.com) from north America created a code but did not oversee its implementation

eEurope Draft Good Practice Guidelines for the Health Internet (europa.eu.int/information_society/eeurope/ehealth/quality/draft_guidelines/) seeks to stimulate the development and implementation of codes of conduct in member states of the European Union

Costs and benefits

Creating codes of conduct has few costs, only an outlay for meetings to draw up the code. But low costs can affect consumers because the absence of any enforcement mechanisms may mean that the code has a limited life.

SUE SHARPLES

Self applied code of conduct or quality label

A quality label (logo or symbol) is displayed on screen and represents a commitment by a provider to implement or adhere to a code of conduct. A site can display the label only after submission of a formal application and acknowledgement of a commitment to the principles. The site may be checked by the label provider, and users may report misuse of the label.

Quality labels

Health On the Net Foundation (www.hon.ch) produces the oldest, and perhaps best known, quality label (currently used by more than 3000 websites)

Hi-Ethics code (www.hiethics.com/Principles/index.asp) produces a quality label, mainly for commercial sites

Costs and benefits

Self applied labels are comparatively cheap for both the site provider and the label provider. The label provider supports a small team that processes applications, maintains random checks of sites displaying its label, and responds to any reports of misuse. The site provider ensures compliance with a simple set of criteria in the design and implementation of the site. Consumers may benefit because their attention is drawn to the importance of the principles inherent in the label. Such benefits must be weighed against the requirement of consumers to understand the nature of the label and, perhaps more importantly, to care about its aims and objectives.

User guidance systems

A user guidance system enables users to check if a site and its contents comply with certain standards by accessing a series of questions from a displayed logo. Tools may be specific, general, or targeted at particular categories of users (box).

User guidance systems

DISCERN (www.discern.org.uk) is a brief questionnaire for users to validate information on treatment choices

NETSCORING (www.chu-rouen.fr/dsii/publi/critqualv2.html) gives guidance on all health related information

QUICK (www.quick.org.uk) provides children with a step by step guide to assessing health related information on the internet

Costs and benefits

The costs to the provider are none, and the costs to the developer of the guide are low, often not extending beyond the initial development costs. However, since the burden of the use of the tool falls entirely on the consumer, the extent to which it is used, and thus its real benefit, may be small.

Filtering tools

Filters, applied manually or automatically, accept or reject whole sites of information based on preset criteria. These tools are based on the “gateway” approach to organising access to the internet—that is, resources are selected for their quality and relevance to a particular audience. The resources are reviewed and classified and the descriptions stored in a database. These tools improve the recall and precision of internet searches for a particular group of consumers—for example, OMNI is aimed at students, researchers, academics, and practitioners in the health and medical sciences (box).

Filtering tools

OMNI (www.biome.ac.uk/guidelines/eval/factors) provides a gateway to evaluated, quality resources in health and medicine

Costs and benefits

The costs of creating a filtering tool are relatively high because trained experts are needed to review and classify the information. Filtering tools provide a valuable shortcut to searches using non-specific search engines.

Quality and accreditation labels awarded by third parties

Quality and accreditation labels are logos or symbols awarded by a third party, usually for a fee, to inform consumers that a site provides information meeting current standards for content and form. This is the most advanced approach for quality rating as a third party provides a label as a result of its own investigation and certifies that the site complies with quality criteria. No third party accreditation bodies are fully operational in Europe yet, although two pilots are running (box).

Third party quality and accreditation labels

MEDCERTAIN (www.medcertain.org/) and TNO QMIC (www.health.tno.nl/en/news/qmic_uk.pdf) are running pilot schemes for third party accreditation bodies in Europe

URAC (www.urac.org/) has started a health website accreditation programme; it recently processed 20 applications by US websites for formal accreditation lasting a year

Costs and benefits

Third parties range from intra-organisation bodies offering their services at low cost, similar to those responsible for the CE mark on electrical goods sold in the European Union, to high cost external independent assessors who perform audits and grant accreditation.

Discussion

So, what is the value of this wide range of tools and applications? No organisation or label has the capacity to identify objectively what is good or bad information. Quality remains an inherently subjective assessment, which depends on the type of information needed, the type of information searched for, and the particular qualities and prejudices of the consumer.

Delamothe questioned the value of codes of conduct, rating instruments, and user guides that have proliferated over the past few years, and urged legislators and policymakers not to add to their number. He argued that consumers will cope with the content of websites as they have coped with other media “unassisted by kitemarks,” despite the reality that “much of their content contains medical information that is wrong, incomplete, and unbalanced from the point of view of anybody except its originators.”6 Yet to argue thus is to misunderstand the objective of most quality rating tools, which is not to inhibit publication, but to provide a system by which consumers can assess the nature of the information they are accessing.

As consumers of traditional media we have learnt to use a wide range of assessment tools. We have learnt to judge the nature of the outlet providing the information (mainstream bookshop or provided by the author), the look and feel of the publication (magazine or one page pamphlet), and we know who to contact for further information (librarian, bookshop assistant, publisher). For the internet, however, we still have to learn to read the signs of quality relevant to our needs. It is for this reason that quality marks and user guides have proliferated. Just as selling a magazine through the right retailer attracts a particular market, so a label such as HON or MedCertain may help consumers assess the information and its provider. It may also allow the provider to gain a foothold in an already crowded market.

It can be argued therefore that labels, codes, and guidance tools that assist consumers to identify information that meets their subjective understanding of quality are useful. However, to argue thus makes one large and fundamentally flawed assumption: that consumers have the time, energy, and inclination to use the tools appropriately—that is, to apply the scoring chart, to check the currency and validity of a label, to access the filtering site, and so on. As such, tools place a burden on consumers, which represents “a serious threat to the sustainability and maintenance of the quality standards.”7

The greatest challenge is not to develop yet more rating tools, but to encourage consumers to seek out information critically, and to encourage them to see time invested in critical searching as beneficial. It may be argued that the only way to do this is to have a centrally controlled system that would offer quality labels on a par with the CE mark or through the adoption of a gold standard code.8,9 It can be argued that no single tool or enforcement body can meet this need. Rather, that consumers will become proficient in accessing health on the internet with time, just as we have become critical consumers of advertising. It can only be hoped that on the road to such savvyness users of the internet for health information will not fall foul of too many ugly sites nor consume too much information that turns out to be bad for them.

Table.

Classification of tools for rating quality of health information on the internet

| Tool | Examples | Costs to approach developer | Costs to site provider | Burden to site user | Key potential beneficiaries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code of conduct | Internet Health Coalition | Low | Low | Medium | Site provider and user |

| American Medical Association | |||||

| Health Summit Working Group | |||||

| eEurope | |||||

| Quality label | Health on the Net | Medium | Medium | Medium | Site provider, site user, label provider |

| Hi-Ethics | |||||

| User guide | DISCERN | Low | None | High | Site provider, site user, information provider |

| NetScoring | |||||

| QUICK | |||||

| Filter | OMNI | Low | None | Low | Site provider, site user, information provider |

| Third party certification | MedCertain | High | High | Low | Site provider, site user, certification provider |

| TNO-QMIC | |||||

| URAC |

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Commission.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Harris Poll. www.harrisinteractive.com/harris_poll/index.asp (accessed 14 Nov 2001).

- 2.Eysenbach G, Eun Ryoung Sa ER, Diepgen TL. Shopping around the internet today and tomorrow: towards the millennium of cybermedicine. BMJ. 1999;319:1294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7220.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLellen F. “Like hunger, like thirst”: patients, journals and the internet. Lancet. 1998;352 (suppl II):39–43S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jadad A, Gagliardi A. Rating health information on the internet: navigation to knowledge or to Babel. JAMA. 1998;279(8):611–614. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gagliardi A, Jadad A. Examination of instruments used to rate quality of health information on the internet: chronicle of a voyage with an unclear destination. BMJ. 2002;324:569–573. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7337.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delamothe T. Quality of websites: kitemarking the west wind. BMJ. 2000;321:843–844. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Risk A, Dzenowagis J. Review of internet health information quality initiatives. J Med Internet Res. 2001;3(4):e288. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3.4.e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigby M, Forsström J, Roberts R, Wyatt J. Verifying quality and safety in health informatics services. BMJ. 2001;323:552–556. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7312.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darmoni SJ, Haugh MC, Lukas B, Boissel JP. Level of evidence should be gold standard [letters] BMJ. 2001;322:1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]