Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Educational strategies for preventive screening and effective interventions in midwives are needed to improve clinical practice and outcomes for abused women and their families. This scoping review aimed to describe available educational training programs on intimate partner violence (IPV) in pregnancy for midwives/student midwives.

METHODS

A scoping review of the literature, which was published in English from January 2010 to March 2023, in PUBMED, EBSCO, and CINAHAL databases, was applied. The following keywords were used in the search: ‘evaluation’, ‘educational training’, ‘course’, ‘midwives’, ‘student midwife’, ‘intimate partner violence’, ‘pregnancy’, combined with AND and OR Boolean operators. The included studies focused on training programs/courses for midwives/student midwives regarding intimate partner violence.

RESULTS

A total of 9 studies were eligible for inclusion, describing six programs for midwives and 3 for student midwives. Educational interventions varied in length (e.g. a few hours to weeks) and educational approaches such as multidisciplinary sessions, lectures, theory, role-playing, practice in screening, group activities, watching videos, and case reports discussion. The programs had similar content, including raising awareness of violence, defining it, discussing gender roles, the impact of IPV on women’s health, referral agencies, and the laws regarding violence in each country.

CONCLUSIONS

This scoping review highlighted a lack of educational programs on intimate partner violence during pregnancy, suggesting that new programs need to be developed based on contemporary clinical practices and recommendations for midwifery education.

Keywords: evaluation, educational training, midwives, student midwife, intimate partner violence, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health problem that affects one-third of women worldwide1. WHO reported that pregnant women are more vulnerable to IPV due to changes in their physical, emotional, social, and economic situation, and defines IPV as ‘the behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors’1.

Meta-analysis of risk factors on violence during pregnancy showed that predictors of abuse during pregnancy included abuse before pregnancy, lower education level, pregnancy being unintended by either the victim or the perpetrator, lower socioeconomic status, and being unmarried2. Immigrant women are more vulnerable to IPV due to their economic insecurity, language barriers, family separation, social isolation, and discrimination3. IPV during pregnancy does not only affect women’s reproductive health but also imposes fatal and non-fatal adverse health outcomes on the growing fetus due to the direct trauma of abuse to a pregnant woman’s body4. IPV prevalence is higher than many common obstetric conditions5, such as first/second trimester bleeding, late entry into antenatal care6, and preterm labor7; moreover, infants of women reporting IPV in pregnancy are more likely to experience low birth weight8, under-nutrition, and higher rates of mortality9. Additionally, women affected by IPV are less likely to breastfeed their babies5 and more likely to experience mother-to-infant bonding failure at one month postnatal10.

Midwives have a central role in the provision of maternity care and are usually the first point of contact with pregnant women; thus, they are expected to routinely and accurately identify and support survivors of IPV11. Developing an empathic relationship with women may allow them to feel safe and confident to discuss sensitive matters like violence in their relationship and further be assessed for IPV12. However, there are a number of barriers for midwives to openly communicate with women who have experienced violence, such as inadequate education and training on the topic and, subsequently, a lack of relevant skills and competencies13. As a result, midwives usually describe reluctance and lack of confidence to discuss IPV-related issues with women14. Nevertheless, addressing experiences of violence in those cared for can be challenging for midwives; adverse emotional responses in midwives, such as shame, criticism, and uncertainty, along with a lack of knowledge and relevant skills, may lead to ignorance of women’s experiences of IPV, and subsequently exclusion of this topic from their care plan15.

Literature suggests that effective educational strategies for midwives are needed to improve their clinical practice and outcomes for abused women and their families11-16.

In education, the inclusion of screening by maternity health professionals has been debated not only in terms of identifying asymptomatic patients but also with a focus on a combination of identifying such patients and subsequently intervening to influence desired outcomes. This intervention may lead to reduced future violence, enhanced quality of life, improved pregnancy outcomes, or similar positive effects16. WHO1 suggested that healthcare providers need to be prepared to provide immediate support and referral to women experiencing IPV. It also recommends IPV training that incorporates safety planning, communication, and referral to specialist agencies and addresses staff attitudes toward victims of IPV. Additionally, the International Confederation of Midwives17 emphasizes the need to strengthen the quality of midwifery education and essential competencies for midwifery practice in its recommendations. These recommendations guide the training of midwives, focusing on crucial aspects. This includes safeguarding privacy and confidentiality, offering information to all women about available sources of help regardless of whether there is disclosure about violence, and routinely inquiring about safety at home and at work. Furthermore, they emphasize recognizing potential signs of abuse from physical appearance and emotional affect, identifying related risk behaviors such as substance abuse, and providing special support for adolescents and victims of gender-based violence, including rape. The recommendations also stress facilitating referrals to community resources while assisting in locating a safe setting as needed.

Training programs need to address common myths associated with violence to prompt positive attitudes, focus on knowledge and preparation for routine inquiry, provide information on local resources, and promote adherence to best practices11. Training programs should not be just for health professionals in the hospitals but also for the student midwives and nurses who have increased knowledge and awareness of violence against women because they will interact with women when they start working in the profession18. Considering that universities’ midwifery programs include curriculum content training in the prevention, detection, and support of victims of IPV19 so that students can act and speak up when there are violations of human rights1.

The aim of this scoping review was to describe available educational training programs for midwives/student midwives regarding intimate partner violence in pregnancy, with a focus on: 1) their features and 2) areas of effectiveness.

METHOD

Study design

A scoping review of the literature took place according to the following steps: 1) report of the objectives of the review, 2) systematic search of scientific data, according to predefined criteria, to collect the sample studies of the study, 3) assessment of the methodological quality of the reviewed studies to be included in the sample, and 4) critical and systematic report of the features and main results of the sample studies. The methodology of the present review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Supplementary file, and reference therein).

Search strategy

Αn advanced search in the following databases was applied: PUBMED, EBSCO, CINAHL, using the following keywords alone and in combination, in line with Medical Subject Headings: ‘evaluation’, ‘educational training’, ‘course’, ‘midwives’, ‘student midwife’, ‘intimate partner violence’, and ‘pregnancy’ and combined with AND and OR Boolean operators. The search strategy was performed in January 2023. A rerun of the search was performed in March of 2023. This search was conducted by two members of the research team (EM, EH).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be considered for inclusion, studies were required to: 1) employ a quantitative research design or to encompass such a design within their methodology (mixed-methods studies), 2) include in the sample midwives and/or student midwives, 3) focus on the effectiveness of a training program or a course, addressing intimate partner violence, 4) be written in English, and 5) be published between January 2010 and March 2023 in a peer-reviewed journal. Conference presentations and articles describing an educational program with no reference to empirically produced data on its effectiveness were excluded.

Two researchers (EM, EH) independently screened the titles and the abstracts of all retrieved articles for eligibility and resolved disagreements by consensus. An extraction sheet to support the data collection procedure and documentation of the reasons for excluding a study was used.

Two members of the research team (EM, EH) assessed the quality of the studies independently, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. No studies were excluded due to low quality. The researchers evaluated the quality of the reviewed studies using the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment tool for cross-sectional studies, the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool for mixed-methods studies (MMAT), and the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Supplementary file Tables 1–3, and references therein).

Furthermore, each study of the sample was independently reviewed by the two researchers (EM, EH) corresponding to the measures employed in the aims of the review, i.e. target population/sample (midwives, healthcare professionals), duration of intervention, educational method and content and key findings. An extraction sheet specially designed to support this process was used for the data collection procedure, and the reason for excluding a study was documented.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed in three steps. The first step involved the identification of studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, the description of their main methodological characteristics, the development of relevant tables, and the assessment of their methodological quality. The final stage encompassed the organization of the results of the sample studies in relation to the present research objectives and the interpretation of data regarding the effectiveness and features of IPV educational programs. Special focus was placed on the barriers regarding the implementation of such programs.

RESULTS

All of the studies were published between 1997 and 2015, and study samples included 4274 nurses working from 3 to 25 years either in the community, mental health, residential care facilities, or hospital units.

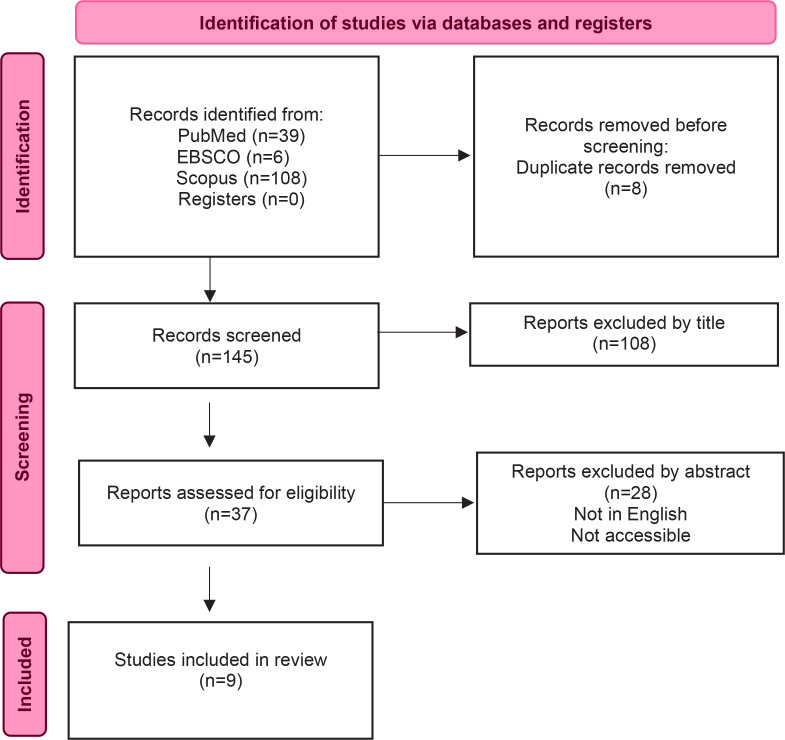

The selection strategy of the sample studies was based on the PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1). The search produced 153 articles. Eight articles were removed as duplicates. One hundred forty-five full-text articles were assessed on relevance. By studying the titles, 108 articles were excluded as they were irrelevant to inclusion criteria objectives. After studying the abstracts of the remaining articles, 28 of them were excluded because they were inaccessible. Only nine articles fulfilled the criterion of assessing the effectiveness of training programs for midwives on IPV. All these nine articles were evaluated and found to be of satisfactory methodological quality according to standardized tools (Supplementary file Tables 1–3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart summary of search strategy and study selection

Study characteristics

More specifically, the characteristics of the nine studies are shown in Table 1. Three studies were pre-post interventions studies, one was a cross-sectional study, three were experimental studies and two were mixed-methods studies. The sample size of health professionals who participated in these studies ranged from 21 to 408 people, including midwives (n=706) and student midwives (n=389). Studies were conducted in Australia (n=3), Europe (n=3), and Asia (n=3). Three studies included midwives and other health professionals, such as obstetricians and nurses12,19,20. A total of six educational programs for midwives and three for student midwives were included in the sample studies. Most of the studies (n=6) identified education strategies for professional midwives who worked in hospital maternity services. One study included community-based midwives while two included educational courses integrated into the midwifery curriculum18,22.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies evaluating educational training programs on intimate partner violence in pregnancy for midwives/student midwives from January 2010 to March 2023

| Study Year Country | Aim | Type of study population | Duration of intervention | Educational method and content | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torres-Vitolas et al.12 2010 United Kingdom | To identify maternity and sexual healthcare professionals’ training needs regarding routine inquiry for domestic abuse (DA) | Cross-sectional study Pre-training questionnaires 222 attendees Maternity and sexual health professionals (including doctors, midwives, and nurses) |

One day domestic abuse (DA) training session | Educational method: multidisciplinary sessions Content: Domestic abuse awareness, practical training for routine inquiry for domestic abuse, documentation, and referral to the advocacy service. |

39.9% of the participants reported limited domestic abuse training. In total, 43.3% of the participants reported that they had encountered at least one disclosure of DA in the 12 months before the training session. 46% of maternity health professionals reported they suspected that a patient was a victim of DA compared to 30.6% of other medical professional staff. |

| Baird et al.24 2013 United Kingdom | To evaluate the degree to which practice changes identified from a previous evaluation of the Bristol Pregnancy Domestic Violence Programme (BPDVP) for routine inquiry for domestic abuse has been maintained | Follow-up study Mixed-methods -semi-structured questionnaires -focus group interviews Five years after the introduction of the training program 58 midwives |

One day program | Educational method: Content:

|

In this study, 61% of the midwives reported their levels of confidence following training on DA increased, compared to 36% in the first study. Generally, the effect of training on knowledge was significantly increased on the screen of asking and responding to domestic violence. |

| Jayatilleke et al.21 2015 Sri Lanka | To evaluate the training program’s efficacy in improving public health midwives’ identification and management of IPV sufferers in Kandy | Pre-post intervention study -pre-post intervention survey at 6 months posttraining 408 public health midwives (PHM) |

Four days of training | Educational method: Using role-playing and case reports, the trainers discussed how to manage IPV sufferers in different situations and improved the PHMs’ practical IPV skills Content:

|

The training program improved practices significantly. 98.5% of midwives identified at least one intimate partner violence suffered compared to pre-intervention rates. All post-intervention scores were at least 50% higher than pre-interview scores (e.g. knowledge, perceived responsibility, self-confidence). |

| Baird et al.11 2018 Australia | To evaluate the longitudinal impact of a domestic violence training and support program to promote midwives’ routine antenatal inquiry for domestic violence using a mixedmethods design | Mixed-methods design-a survey of midwives at 6 months post-training, -interviews with key stakeholders at 12 months -chart audit data of screening, risk, and disclosure rates (for 16 months). 83 midwives |

Seven-hour workshop | Educational method: Included a variety of teaching approaches such as group activities, role-play, and analysis of case studies. Content:

|

This study identifies that all follow-up scores were significantly higher than baseline scores. The score for level of preparedness increased by 20%, and knowledge increased by 17%. More than 90% of participants reported improved confidence to undertake the routine inquiry. The chart audit showed that 90% of the women were screened. Only 2% of the women screened disclosed domestic violence, and most women at risk refused the referral. |

| Baird et al.25 2018 Australia | To evaluate the impact of training on the knowledge and preparedness of midwives and nurses to conduct a routine inquiry about domestic violence (DV) with women during the perinatal period | Pre-post intervention study -pre-post questionnaire 149 Midwives |

One day workshop | Educational method: Teaching approaches included lectures, group activities, videos, role-play, and analysis of case studies. Group work sessions encouraged discussion around topics such as what constitutes violence against women and why women may choose to stay with a violent partner. Content:

|

All post-intervention scores were significantly higher than pre-interview scores (knowledge, preparedness). The score for level of knowledge increased by 19%, and preparedness increased by 31%. 93% of midwives reported the training program improved their awareness of domestic violence and improved their skills for screening and how to respond to a woman’s disclosure of domestic violence. |

| Smith et al.23 2018 Australia | To increase midwifery students’ confidence in screening for and responding to disclosure of domestic violence in maternity service | Mix-Methods study (quantitative and qualitative questions) 174 student midwives |

One day workshop | Educational method: Theory and practice in regard to screening for and responding to domestic violence in pregnancy. Content:

|

Midwifery students increased their confidence by responding appropriately to disclosure and assisting women with access to support. The largest increase (47%) in students’ confidence levels was the score for the topic area ‘Providing an appropriate response if the woman discloses current domestic violence’. |

| Yilmaz22 2018 Turkey | To evaluate the effectiveness of a gender equality course in changing undergraduate midwifery students’ attitudes toward domestic violence and gender roles | One-group before-after quasi-experimental design ‘The Attitudes Towards Domestic Violence Scale’ and ‘The Gender Roles Attitudes Scale’ First-year undergraduate midwifery students (n=64) |

Course: 10 sessions for 2 hours | Educational method: Used case reports, visual presentations, and discussions. Content: The gender equality course consisted of two parts. The first part, which related to gender roles, was structured based on the related literature (World Health Organization, 2006; Prime Ministry Directorate General on the Status of Women, 2008b; World Health Organization, 2009; Ecevit et al. 2011; Dökmen 2016). The second part related to DV was structured based on the related literature also (Berman, Barlow, Koziol-McLain, 2005; Jayatilleke et al. 2015; Crombie, Hooker, Reisenhofer 2016). |

The course helped the students to develop more positive attitudes toward domestic violence and gender roles. The scores for the attitudes towards domestic violence only increased by a few percent, while the scores for attitudes to gender roles increased by 7%. |

| Sis Çelik and Aydın18 2019 Turkey | To determine the effect of a course on violence against women on the attitudes of student midwives and nurses towards violence against women and their abilities to recognize the signs of violence | Pretest-post test quasi-experimental design with experimental and control groups. Questionnaire N=78 student midwives and nurses’ experimental group (enrolled in the course) N=73 student midwives and nurses control group (did not choose to enroll in the course) |

Course on violence against women: 2-hour lecture every week for 14 weeks, for a t otal of 28 hours |

Educational method: Presentations Content:

|

The results indicated that the difference between pretest and post-test scores averaged across three scales(attitudes towards violence (25%), attitudes of healthcare personnel towards occupational roles in addressing violence against women (29%), and the ability of nurses and midwives to recognize the signs of violence against women (41%) was statistically significant for students in the experimental group and statistically insignificant for students in the control group. |

| Duchesne et al.20 2020 France | To assess the impact of a brief training for obstetricians and midwives about screening for domestic violence during pregnancy follow-up and to identify barriers to a routine inquiry | Quasi-experimental study -Patients’ survey 13 obstetricians and 8 midwives – attended the intervention 495 patients in the control group 395 experimental group |

One hour-anda-half training session | Educational method: Presentations were performed using PowerPoint software. Presenters gave further details, examples, and answered questions if asked. Content: The intervention provided general information about domestic violence to alert health professionals (prevalence, risk factors, consequences on women’s health, pregnancy, and children) and guidelines on screening and how to deal with women disclosing domestic violence. |

Only 4.1% of patients were screened for domestic violence during pregnancy followup. The 38.1% of healthcare professionals had never screened for domestic violence, only 14.3% stated they always did. The study identified the following barriers to screening: the presence of the partner, the lack of awareness of the need to screen, uncomfortable feelings, and the difficulty of identifying victims. |

Duration

Educational interventions varied in length, ranging from one hour and a half 20 to 14 weeks – 2 hours of course18. Programs that targeted health professionals were short-lasting one day or less23. In contrast, programs that targeted students lasted 10–14 weeks18,22. One study included a one-day workshop for student midwives23.

Educational method and content

The educational programs included a variety of educational approaches such as group activities, role play, and analysis of case studies. Furthermore, most researchers focused on group activities, as resolving IPV cases during pregnancy requires a team effort. On the contrary, only 2 of the educational programs used the traditional method of delivering knowledge through presentations18,20. The programs had similar content, including raising awareness of violence, defining it, discussing gender roles, the impact of IPV on women’s health, referral agencies, and the laws regarding violence in each country. Two of the studies included survivor experiences of maternity care during pregnancy24,25. The effect of IPV on child health was addressed in 3 studies20,23,25. Experts in gender-based violence, including midwives, academics, doctors, and psychologists, designed most of the programs.

An overview of all the characteristics of educational training programs on intimate partner violence during pregnancy for midwives and student midwives is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the characteristics of Educational Training Programs on intimate partner violence during pregnancy for midwives and student midwives from January 2010 to March 2023

| Characteristics | Specific characteristics |

|---|---|

| Duration |

|

| Educational method |

|

| Content |

|

Previous experience with IPV training

Five studies (n=5) reported that the majority of participants in their studies had not received any other IPV-related education before the educational intervention. Furthermore, maternity professionals were significantly more likely to have received training for IPV than genitourinary medicine professionals12. Additionally, it has also been shown that even midwives and midwifery students had limited knowledge or experience of violence against women18.

Areas of effectiveness of the reviewed educational programs on IPV

One study11 showed an improvement in participant midwives’ knowledge about IPV during pregnancy. Furthermore, this study concluded that following the educational program, midwives felt more confident in assessing abusive experiences, especially during antenatal visits. Another study21 reported that following the educational program, most participant midwives were able to identify at least one IPV survivor three months after the intervention.

Several studies11,21,24,25 reported that training on IPV increased participants’ knowledge, self-perceived responsibility for the identification of the victims, and self-confidence in supporting women who had experienced violence. The knowledge on screening women for abuse was increased in more than 60% of the participants, specifically in the areas of abuse disclosures, awareness of referral pathways, and how to work with multidisciplinary teams to support women who had experienced abuse25.

Students developed more positive attitudes toward violence and gender roles following the training22,23. Furthermore, their confidence levels increased in four areas: responding to and discussing domestic violence with women, assisting women in accessing support, discussing women’s experiences of violence, and accessing support for themselves after working with a woman who discloses violence. Professionals mentioned several barriers to screening pregnant women for IPV, including the presence of the partner, a lack of awareness of the need to screen, uncomfortable feelings, and difficulty identifying victims20. Additionally, some professionals felt that their workplace did not allow adequate time to respond to disclosures of IPV25.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the scoping review highlighted the lack of educational programs for intimate partner violence in pregnancy for the professionals and students of midwifery, as most of them had not received any training26. Midwives often feel unprepared to work with women in this important area of midwifery practice23. ΙPV knowledge of the midwives and nurses was poor, as reflected by their very low percentage of correct answers of general knowledge about violence27. These inadequacies in knowledge, attitudes, and practices could affect the care of those who experienced IPV as a result of their negative experiences in healthcare28.

Additionally, some students had little sensitivity to the subject and wrong ideas about violence, and over half of students reported that the subject was not addressed in their program of study29. However, after the training, results show improved knowledge and promoted preparatory/reinforcing behaviors30. Studies suggest that health services and workplaces that incorporated training on IPV and had clear referral pathways helped midwives to routinely ask pregnant women about IPV, and they felt more confident in managing positive disclosures31. Furthermore, IPV education for midwives is imperative to commence at the undergraduate level and continue post-registration to ensure skills and knowledge base are maintained16. It has also been shown that pregnant women in antenatal settings may be more likely to disclose IPV when screened by professionals32.

Fortunately, there are a number of tools to diagnose IPV (in all forms: physical, sexual, and psychological) in pregnant women33. For example, the RADAR tool34 includes the following steps: 1) Routinely screen adult patients, 2) Ask direct questions, 3) Document your findings, 4) Assess patient safety, and 5) Review options and referrals. Another tool is the HITS Tool for domestic violence (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream). This self-report tool has been used in different populations and both genders and provides a sense of privacy as it does not ask for details. Finally, the HITS tool is not time-consuming as it only includes four questions using the Likert scale. Finally, the most widely used IPV screening tool in the pregnant population is the AAS Tool34. AAS is a five-item screening tool including the following questions: 1) ‘Have you ever been afraid of your partner or someone else?’; 2) ‘Have you ever experienced that a partner or ex-partner has done things to make you feel afraid of them?’; and 3) ‘Done things to try to intimidate you or to control your thoughts, feelings or actions? Hit, kicked, pulled you by your hair or otherwise physically hurt you? Forced you to have sexual activities against your will?’. Finally the AAS tool has been tested in obstetrics–gynaecology outpatient practices and among different ethnicities31.

More recently, during the lockdown periods because of COVID-19, there was a pilot study in a large US healthcare establishment that utilized an application (i.e. MyHealthyPregnancy app) to monitor risks during pregnancy, including IPV. Through this application, patients can be screened for IPV remotely. For example, users received in-app messages that stated: ‘Are you concerned about your safety? Take the pregnancy safety quiz’, etc. The study showed a slight increase in IPV during lockdowns35.

This scoping review confirms that midwives prefer to develop a relationship with women before asking about IPV36. This finding emphasizes the need for an organizational change in the healthcare setting to adequately respond to IPV27, with continuity of education and midwifery care being the key. As long as health professionals keep being quiet about violence, the victims will carry on avoiding sharing their experiences and worries.

Strengths and limitations

A notable advantage of this review is that most items outlined were conducted separately by two assessors. The strengths of this study are based on the satisfactory number of primary studies included in the review covering a wide range of implementation years.

Several limitations to this review study need to be acknowledged. During the literature search, only studies containing the keyword midwives were included. However, due to the limited number of studies involving registered midwives, studies involving student midwives had to be included to broaden the scope of this review. Studies including health professionals who were not identified as midwives were excluded.

Another limitation of this study is the unavoidable introduction of language bias due to the use of articles in the English language only. Furthermore, the studies included in this review described educational programs in Asia, Europe, and Australia. The absence of studies from America and Africa is noted. It is, therefore, recognized that programs in many parts of the world that are given in different languages may exist but remain unpublished. However, further in-depth research will be required to ensure global knowledge about published or unpublished programs for registered midwives and midwifery students.

CONCLUSIONS

The educational programs for intimate partner violence can be beneficial for professional midwives and students despite their lack. These programs could impart knowledge and skills to participants to identify incidents of intimate partner violence, address them, and protect abused pregnant women. There is an urgent need to create new programs that must adapt to new clinical practices and recommendations for midwifery education on intimate partner violence during pregnancy. These new programs should be integrated into midwifery university programs, as well as in continuing education programs for midwives who work in hospitals, the community, or are independent. Recognizing the problem can be the best way to prevent it. Future research will concentrate on utilizing the results of this research to create a new educational program and to investigate the effectiveness of knowledge and preparedness of midwives to conduct routine inquiries about intimate partner violence with women during pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In Memory of Christiana Kouta.

Funding Statement

FUNDING There was no source of funding for this research.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have each completed and submitted an ICMJE form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise, related to the current work. N. Middleton reports that he is an unpaid Member of Board of the Scientific Society of the Cyprus Epidemiology and Public Health Association.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

Ethical approval was obtained from the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (Approval number: EEBK EΠ 2020.01.137).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting this research are available from the authors on reasonable request.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization . Global status report on violence prevention 2014. World Health Organization; 2014. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/145086/9789241564793_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 2.James L, Brody D, Hamilton Z. Risk factors for domestic violence during pregnancy: a meta-analytic review. Violence Vict. 2013;28(3):359-380. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.vv-d-12-00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Du Mont J, Forte T. An exploratory study on the consequences and contextual factors of intimate partner violence among immigrant and Canadian-born women. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e001728. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chai J, Fink G, Kaaya S, et al. Association between intimate partner violence and poor child growth: results from 42 demographic and health surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(5):331-339. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.152462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-de-Las-Heras S, Velasco C, Luna-Del-Castillo JD, Khan KS. Maternal outcomes associated to psychological and physical intimate partner violence during pregnancy: A cohort study and multivariate analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam MJ, Broidy L, Baird K, Mazerolle P. Exploring the associations between intimate partner violence victimization during pregnancy and delayed entry into prenatal care: Evidence from a population-based study in Bangladesh. Midwifery. 2017;47:43-52. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigalla GN, Rasch V, Gammeltoft T, et al. Social support and intimate partner violence during pregnancy among women attending antenatal care in Moshi Municipality, Northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4157-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferraro AA, Rohde LA, Polanczyk GV, et al. The specific and combined role of domestic violence and mental health disorders during pregnancy on new-born health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):257. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1438-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill A, Pallitto C, McCleary-Sills J, Garcia-Moreno C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and selected birth outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;133(3):269-276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kita S, Haruna M, Matsuzaki M, Kamibeppu K. Associations between intimate partner violence (IPV) during pregnancy, mother-to-infant bonding failure, and postnatal depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(4):623-634. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0603-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baird K, Creedy DK, Saito AS, Eustace J. Longitudinal evaluation of a training program to promote routine antenatal enquiry for domestic violence by midwives. Women Birth. 2018;31(5):398-406. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres-Vitolas C, Bacchus LJ, Aston G. A comparison of the training needs of maternity and sexual health professionals in a London teaching hospital with regards to routine enquiry for domestic abuse. Public Health. 2010;124(8):472-478. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnbogadóttir H, Torkelsson E, Christensen CB, Persson EK. Midwives experiences of meeting pregnant women who are exposed to Intimate-Partner Violence at in-hospital prenatal ward: A qualitative study. Eur J Midwifery. 2020;4:35. doi: 10.18332/ejm/125941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eustace J, Baird K, Saito AS, Creedy DK. Midwives’ experiences of routine enquiry for intimate partner violence in pregnancy. Women Birth. 2016;29(6):503-510. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprague S, Swinton M, Madden K, et al. Barriers to and facilitators for screening women for intimate partner violence in surgical fracture clinics: a qualitative descriptive approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crombie N, Hooker L, Reisenhofer S. Nurse and midwifery education and intimate partner violence: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(15-16):2100-2125. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice. International Confederation of Midwives. Updated January 4, 2024. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://internationalmidwives.org/resources/essential-competencies-for-midwifery-practice/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sis Çelik A, Aydın A. The effect of a course on violence against women on the attitudes of student midwives and nurses towards domestic violence against women, their occupational roles in addressing violence, and their abilities to recognize the signs of violence. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;55(2):210-217. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gómez-Fernández MA, Goberna-Tricas J, Payà-Sánchez M. Intimate partner violence as a subject of study during the training of nurses and midwives in Catalonia (Spain): A qualitative study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;27:13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duchesne S, Donnadieu AC, Chariot P, Louis-Sylvestre C. Screening for domestic violence during pregnancy follow-up: evaluation of an intervention in an antenatal service. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(2):293-301. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jayatilleke AC, Yoshikawa K, Yasuoka J, et al. Training Sri Lankan public health midwives on intimate partner violence: a pre- and post-intervention study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:331. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1674-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bahadir Yilmaz E. The effectiveness of a gender equality course in changing undergraduate midwifery students’ attitudes towards domestic violence and gender roles. Cent Eur J Nurs Midwifery. 2018;9(2):840-847. doi: 10.15452/cejnm.2018.09.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith R, Wight R, Homer CSE. ‘Asking the hard questions’: Improving midwifery students’ confidence with domestic violence screening in pregnancy. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;28:27-33. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird K, Salmon D, White P. A five year follow-up study of the Bristol pregnancy domestic violence programme to promote routine enquiry. Midwifery. 2013;29(8):1003-1010. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baird KM, Saito AS, Eustace J, Creedy DK. Effectiveness of training to promote routine enquiry for domestic violence by midwives and nurses: A pre-post evaluation study. Women Birth. 2018;31(4):285-291. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambikile JS, Leshabari S, Ohnishi M. Nurses' and midwives' awareness of intimate partner violence-related mental healthcare and associated factors in Tanzania. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;29(4):947-956. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maruyama N, Kataoka Y, Horiuchi S. Effects of e-learning on the support of midwives and nurses to perinatal women suffering from intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2022;19(2):e12464. doi: 10.1111/jjns.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali P, McGarry J, Younas A, Inayat S, Watson R. Nurses’, midwives’ and students’ knowledge, attitudes and practices related to domestic violence: A cross-sectional survey. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(6):1434-1444. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson M, Doran F, Brown J, et al. A cross-sectional study of domestic violence instruction in nursing and midwifery programs: Out of step with community and student expectations. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;84:104209. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Divakar U, Nazeha N, Posadzki P, et al. Digital Education of Health Professionals on the Management of Domestic Violence: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(5):e13868. doi: 10.2196/13868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henriksen L, Garnweidner-Holme LM, Thorsteinsen KK, Lukasse M. ‘It is a difficult topic’ - a qualitative study of midwives´ experiences with routine antenatal enquiry for intimate partner violence. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1352-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, Davidson LL, Feder G, Taft A. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(7):CD007007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007007.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arkins B, Begley C, Higgins A. Measures for screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(3-4):217-235. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deshpande NA, Lewis-O’Connor A. Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2013;6(3-4):141-148. doi: 10.3909/riog0226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnamurti T, Davis AL, Quinn B, Castillo AF, Martin KL, Simhan HN. Mobile Remote Monitoring of Intimate Partner Violence Among Pregnant Patients During the COVID-19 Shelter-In-Place Order: Quality Improvement Pilot Study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e22790. doi: 10.2196/22790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creedy DK, Baird K, Gillespie K. A cross-sectional survey of pregnant women’s perceptions of routine domestic and family violence screening and responses by midwives: Testing of three new tools. Women Birth. 2020;33(4):393-400. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research are available from the authors on reasonable request.