Abstract

BACKGROUND

Desmoid tumors are rare, locally aggressive, highly recurrent soft-tissue tumors without approved treatments.

METHODS

We conducted a phase 3, international, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nirogacestat in adults with progressing desmoid tumors according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. Patients were assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive the oral γ-secretase inhibitor nirogacestat (150 mg) or placebo twice daily. The primary end point was progression-free survival.

RESULTS

From May 2019 through August 2020, a total of 70 patients were assigned to receive nirogacestat and 72 to receive placebo. Nirogacestat had a significant progression-free survival benefit over placebo (hazard ratio for disease progression or death, 0.29; 95% confidence interval, 0.15 to 0.55; P<0.001); the likelihood of being event-free at 2 years was 76% with nirogacestat and 44% with placebo. Between-group differences in progression-free survival were consistent across prespecified subgroups. The percentage of patients who had an objective response was significantly higher with nirogacestat than with placebo (41% vs. 8%; P<0.001), with a median time to response of 5.6 months and 11.1 months, respectively; the percentage of patients with a complete response was 7% and 0%, respectively. Significant between-group differences in secondary patient-reported outcomes, including pain, symptom burden, physical or role functioning, and health-related quality of life, were observed (P≤0.01). Frequent adverse events with nirogacestat included diarrhea (in 84% of the patients), nausea (in 54%), fatigue (in 51%), hypophosphatemia (in 42%), and maculopapular rash (in 32%); 95% of adverse events were of grade 1 or 2. Among women of childbearing potential receiving nirogacestat, 27 of 36 (75%) had adverse events consistent with ovarian dysfunction, which resolved in 20 women (74%).

CONCLUSIONS

Nirogacestat was associated with significant benefits with respect to progression-free survival, objective response, pain, symptom burden, physical functioning, role functioning, and health-related quality of life in adults with progressing desmoid tumors. Adverse events with nirogacestat were frequent but mostly low grade. (Funded by SpringWorks Therapeutics; DeFi ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03785964.)

Desmoid tumors, or aggressive fibromatosis, are rare, soft-tissue tumors that are diagnosed in approximately 3 to 5 persons per million annually. Although they are not metastatic, desmoid tumors are locally aggressive and invasive, leading to substantial illness but rarely death.1–3 Compression of vital structures by desmoid tumors can result in severe pain, functional impairment, nerve damage, and bowel obstruction or perforation.1,2,4 In addition, desmoid tumor–specific symptoms can negatively affect school, work, and psychosocial functioning.5 Pain is associated with disease progression and can lead to opioid dependence or suboptimal pain management owing to concerns about the development of opioid dependence.6,7

Management of desmoid tumors is challenging because of their variable presentation and unpredictable disease course, with spontaneous regression seen in up to 20 to 30% of patients over time.8–12 Currently, no therapies are approved, and existing management guidelines vary depending on tumor location, symptoms, and disease progression. Treatment approaches can incorporate periods of active surveillance, as well as interventions including surgery, cytotoxic chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, local ablation, or radiation therapy.12–15 Surgery, which used to be the mainstay of treatment, has become less frequent owing to high morbidity and postsurgical recurrence rates of up to 50 to 88%.12,16,17

Desmoid tumors are typically characterized by genetic mutations in the Wnt–adenomatous polyposis coli–β-catenin pathway (CTNNB1 [approximately 90%; primarily in sporadic-type desmoid tumors] and APC [approximately 10%; seen in desmoid tumors associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Gardner’s syndrome]), which are thought to contribute to the oncogenic growth of these tumors.1,4,6,18 Along with overexpression of β-catenin, desmoid tumors highly express Notch1, with cross-talk between these pathways putatively contributing to proliferation of desmoid tumors.19–21 Overactivation of the Notch pathway in desmoid tumors may be regulated by γ-secretase inhibitors, because these drugs block Notch signaling through selective inhibition of γ-secretase–mediated cleavage of Notch receptors.18,22–24 Nonclinical studies have shown that γ-secretase inhibition prevents release of the Notch intracellular domain, which blocks Notch pathway signaling and cell growth.25 The mechanism of action of nirogacestat — an investigational, oral, small-molecule, selective γ-secretase inhibitor — in desmoid tumors is not yet fully elucidated. In phase 1 and 2 trials, nirogacestat showed antitumor activity in patients with desmoid tumors; patient-reported pain palliation was also observed.26–28 Here, we describe the efficacy and safety of nirogacestat in a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving patients with progressing desmoid tumors.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND PATIENTS

The DeFi (Desmoid Fibromatosis) trial was a phase 3, international, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine the efficacy and safety of nirogacestat in patients 18 years of age or older with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of progressing desmoid tumors (defined as ≥20% progression according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST], version 1.1, within 12 months before screening). Eligible patients either had not received previous treatment for progressing desmoid tumors that were not amenable to surgery or had refractory or recurrent desmoid tumors after at least one line of therapy.

Patients were stratified according to the location of the target tumor (i.e., intraabdominal [including the mesentery and pelvis] or extraabdominal [including the head or neck, paraspinal regions, arms or legs, abdominal wall, and chest wall]) and were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive oral nirogacestat (150 mg) or placebo twice daily, taken continuously in 28-day cycles. Patients with multiple target tumors located in both intraabdominal and extraabdominal locations were classified as having intraabdominal tumors.

Patients continued to receive nirogacestat or placebo until one of the following events or circumstances occurred, as defined by the trial protocol (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org): death, trial completion, imaging-based or investigator-determined clinical progression (as defined below), an intolerable adverse event, circumstances that prevented the patient from adhering to the trial protocol, or patient or investigator request for discontinuation. Dose reduction to 100 mg twice daily was mandated by the protocol for the management of selected, persistent adverse events of grade 3 or higher (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, skin toxic effects, hypophosphatemia, and hematologic or nonhematologic toxic effects) and was optional for grade 2 ovarian dysfunction.

After imaging-based progression or completion of the primary analysis, the trial-group assignment was revealed to the patient. If eligible, patients were given the option to enroll in an open-label extension phase.

TRIAL OVERSIGHT

This trial was conducted in accordance with ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and all applicable laws, regulations, and scientific guidelines. All the patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. An independent data monitoring committee monitored the unblinded safety data and benefit–risk profile. Details on trial design, oversight, data collection, analysis, and manuscript preparation are included in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and for the adherence of the trial to the protocol. The trial sponsor paid for medical writing and editorial assistance with an earlier version of the manuscript.

END POINTS AND ASSESSMENTS

The primary end point was progression-free survival, defined as the time from randomization until the date of imaging-based or clinical progression or death. Imaging-based progression was determined according to RECIST, version 1.1, for target tumors identified by the investigator at screening. Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomographic scans were obtained at screening, cycle 4, and every three cycles thereafter. Investigator-determined clinical progression was defined as the onset or worsening of symptoms resulting in a global deterioration of health status, which led to the permanent discontinuation of nirogacestat or placebo and the initiation of other treatment for desmoid tumors. Both imaging-based and clinical progression were confirmed by blinded independent central review. The median time to progression or response and progression-free survival in prespecified subgroups were also assessed (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Prespecified secondary efficacy end points were confirmed objective response (defined as complete response or partial response according to RECIST, version 1.1) and the change from baseline at cycle 10 in the following patient-reported outcomes: the Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form (BPI-SF) average worst pain intensity score, the Gounder–Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale (GODDESS)2 Desmoid Tumor Symptom Scale (DTSS) total symptom score, the GODDESS Desmoid Tumor Impact Scale (DTIS) physical functioning domain score, and scores on the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) scales for global health status–quality of life, physical functioning, and role functioning (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Cycle 10 was selected as the predefined time point for assessment of patient-reported outcomes to allow adequate time for a treatment response to be observed. Patients completed at-home questionnaires for patient-reported outcomes using an electronic device at prespecified time points (see the Supplementary Appendix).

Adverse events that emerged or worsened from the time of the first dose of nirogacestat or placebo through 30 days after the last dose were reported and coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 24.0. The severity of adverse events was classified according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0. Clinical laboratory tests, including measurement of levels of reproductive hormones, were routinely performed (see the Supplementary Appendix).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We determined that approximately 51 events of disease progression or death would provide the trial with 90% power to detect a hazard ratio of 0.4, at a one-sided alpha level of 0.025 (as specified in the protocol), for nirogacestat relative to placebo in the intention-to-treat population. Progression-free survival was summarized by means of the Kaplan–Meier method, with the hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval estimated with the use of a Cox proportional-hazards model controlling for the stratification factor of location of the target tumor. The same method was used to assess the consistency of the between-group difference in progression-free survival among 28 prespecified desmoid tumor–specific patient characteristics. Results that are most relevant to the population of patients with desmoid tumors are presented.

The secondary efficacy end points were tested hierarchically in the intention-to-treat population in the following order: objective response, BPI-SF average worst pain intensity score, GODDESS DTSS total symptom score, GODDESS DTIS physical functioning domain score, EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status–quality of life score, EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning score, and EORTC QLQ-C30 role functioning score. The percentage of patients with an objective response was compared between trial groups with the use of the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, with stratification according to tumor location. Time to first response (not part of the testing hierarchy) was summarized with the use of the Kaplan–Meier method. The change in patient-reported outcomes from baseline to cycle 10 was analyzed with the use of a restricted maximum likelihood–based repeated-measures approach and included data from all scheduled time points through cycle 10, for which at least 10 patients in each trial group had nonmissing data. This model included trial group, time point, and trial group by time point as fixed-effect categorical factors and the baseline score for the patient-reported outcomes and the stratification factor as fixed-effect covariates. Differences in patient-reported outcomes between the two groups were calculated as estimates of least-squares mean change. According to Journal guidelines, P values were recalculated ad hoc and reported as two-sided P values with an alpha level of 0.05 for all primary and secondary efficacy end points.

Descriptive analyses of safety included all the patients who received at least one dose of nirogacestat or placebo. Adverse events were reported up to the data-cutoff date for the primary analysis, with additional follow-up performed to assess for adverse events of ovarian dysfunction.

RESULTS

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

From May 2019 through August 2020, a total of 142 patients underwent randomization (with 70 assigned to the nirogacestat group and 72 to the placebo group) across 37 sites in the United States, Canada, and Europe (Fig. S2). Baseline characteristics were generally similar across trial groups and representative of the population of patients with desmoid tumors (Table 1 and Table S1). The median age of the patients was 34.0 years (range, 18 to 76). A total of 37 patients in each group were women of childbearing potential (53% of the patients in the nirogacestat group and 51% of those in the placebo group), as determined by the investigator to be women between menarche and confirmed menopause (i.e., 12 months since last menstruation) with intact ovarian function. A high proportion of patients with multifocal disease were enrolled (27 [39%] in the nirogacestat group and 31 [43%] in the placebo group). Overall, 110 patients (77%) had received previous systemic therapies or radiation therapy or had undergone surgery.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics in the Intention-to-Treat Population.*

| Characteristic | Nirogacestat (N = 70) | Placebo (N = 72) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) — yr | 33.5 (18–73) | 34.5 (18–76) |

| Sex — no. (%) | ||

| Female | 45 (64) | 47 (65) |

| Women of childbearing potential† | 37 (53) | 37 (51) |

| Male | 25 (36) | 25 (35) |

| Race — no. (%)‡ | ||

| White | 64 (91) | 54 (75) |

| Black | 4 (6) | 5 (7) |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 3 (4) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 10 (14) |

| Ethnic group — no. (%)‡ | ||

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 67 (96) | 55 (76) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (1) | 9 (12) |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 8 (11) |

| Geographic region — no. (%) | ||

| United States or Canada | 44 (63) | 53 (74) |

| Europe | 26 (37) | 19 (26) |

| Target-tumor location — no. (%) | ||

| Intraabdominal | 17 (24) | 18 (25) |

| Extraabdominal | 53 (76) | 54 (75) |

| Focal category — no. (%) | ||

| Single | 43 (61) | 41 (57) |

| Multifocal | 27 (39) | 31 (43) |

| Median target-tumor size according to RECIST (IQR) — mm | 91.6 (64.7–134.1) | 115.70 (73.5–161.7) |

| Family history of FAP — no. (%) | 11 (16) | 13 (18) |

| Somatic mutation — no. (%)§ | 52 (74) | 53 (74) |

| APC | 11 (16) | 11 (15) |

| CTNNB1 | 43 (61) | 42 (58) |

| No identified mutation | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Not analyzed | 18 (26) | 18 (25) |

| Treatment status — no. (%) | ||

| No previous treatment | 18 (26) | 14 (19) |

| Refractory or recurrent disease after previous treatment | 52 (74) | 58 (81) |

| Median no. of lines of previous therapy (range) | 2 (0–14) | 2 (0–19) |

| Previous therapies — no. (%) | ||

| Any previous therapy | 52 (74) | 58 (81) |

| Surgery | 31 (44) | 44 (61) |

| Radiation therapy | 16 (23) | 16 (22) |

| Systemic therapy | 43 (61) | 44 (61) |

| Chemotherapy | 24 (34) | 27 (38) |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 23 (33) | 24 (33) |

| Sorafenib | 17 (24) | 18 (25) |

| ECOG performance-status score — no. (%) | ||

| 0 | 51 (73) | 52 (72) |

| 1 | 18 (26) | 20 (28) |

| 2 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Uncontrolled pain — no. (%)¶ | 27 (39) | 31 (43) |

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. ECOG denotes Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, FAP familial adenomatous polyposis, IQR interquartile range, and RECIST Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Women of childbearing potential were defined in the trial protocol as women between menarche and confirmed menopause (i.e., 12 months since last menstruation) with intact ovarian function. The determination of whether trial patients met this definition was based on the investigator's judgment.

Race and ethnic group were reported by the patients.

Samples that could be evaluated were not available for all the patients.

Uncontrolled pain was defined as a Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form average worst pain intensity score of more than 4 (range, 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse pain). Scores were calculated as the average of the daily scores for worst pain during the 7-day period before the baseline visit.

EFFICACY

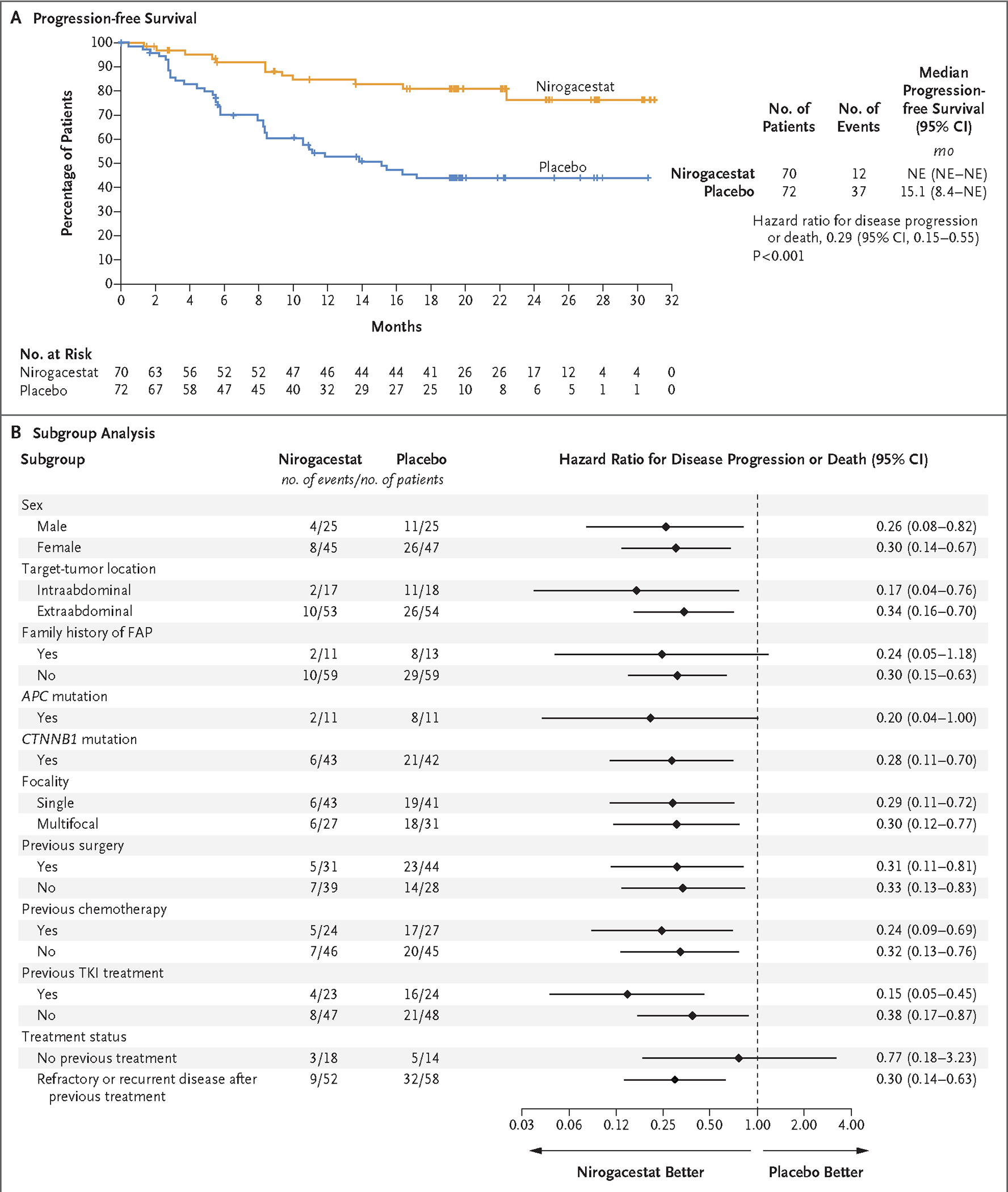

As of the data-cutoff date (April 7, 2022), the overall median follow-up for progression-free survival was 15.9 months. A total of 49 events of disease progression or death were observed (12 in the nirogacestat group and 37 in the placebo group). Observed events were imaging-based progression (in 11 patients in the nirogacestat group and 30 in the placebo group), qualified clinical progression (in 1 and 6, respectively), and death (in 0 and 1, respectively). The risk of disease progression or death was 71% lower in the nirogacestat group than in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.29; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.15 to 0.55; P<0.001) (Fig. 1A). The Kaplan–Meier estimated median progression-free survival could not be estimated in the nirogacestat group as a result of the low number of events and was 15.1 months (95% CI, 8.4 to not estimable) in the placebo group. The likelihood of being event-free at 1 year was 85% (95% CI, 73 to 92) with nirogacestat and 53% (95% CI, 40 to 64) with placebo. The likelihood of being event-free at 2 years was 76% (95% CI, 61 to 87) with nirogacestat and 44% (95% CI, 32 to 56) with placebo. In subgroup analyses of progression-free survival, results were generally consistent across subgroups defined according to sex, tumor location, focality, treatment status, previous treatments, genetic mutation status, and history of familial adenomatous polyposis (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Progression-free Survival and Subgroup Analysis.

Panel A shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival. Progression was determined through blinded, independent, central review and included imaging-based progression according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), version 1.1, and clinical progression. Panel B shows a forest plot of progression-free survival in prespecified subgroups. FAP denotes familial adenomatous polyposis, NE not estimable, and TKI tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

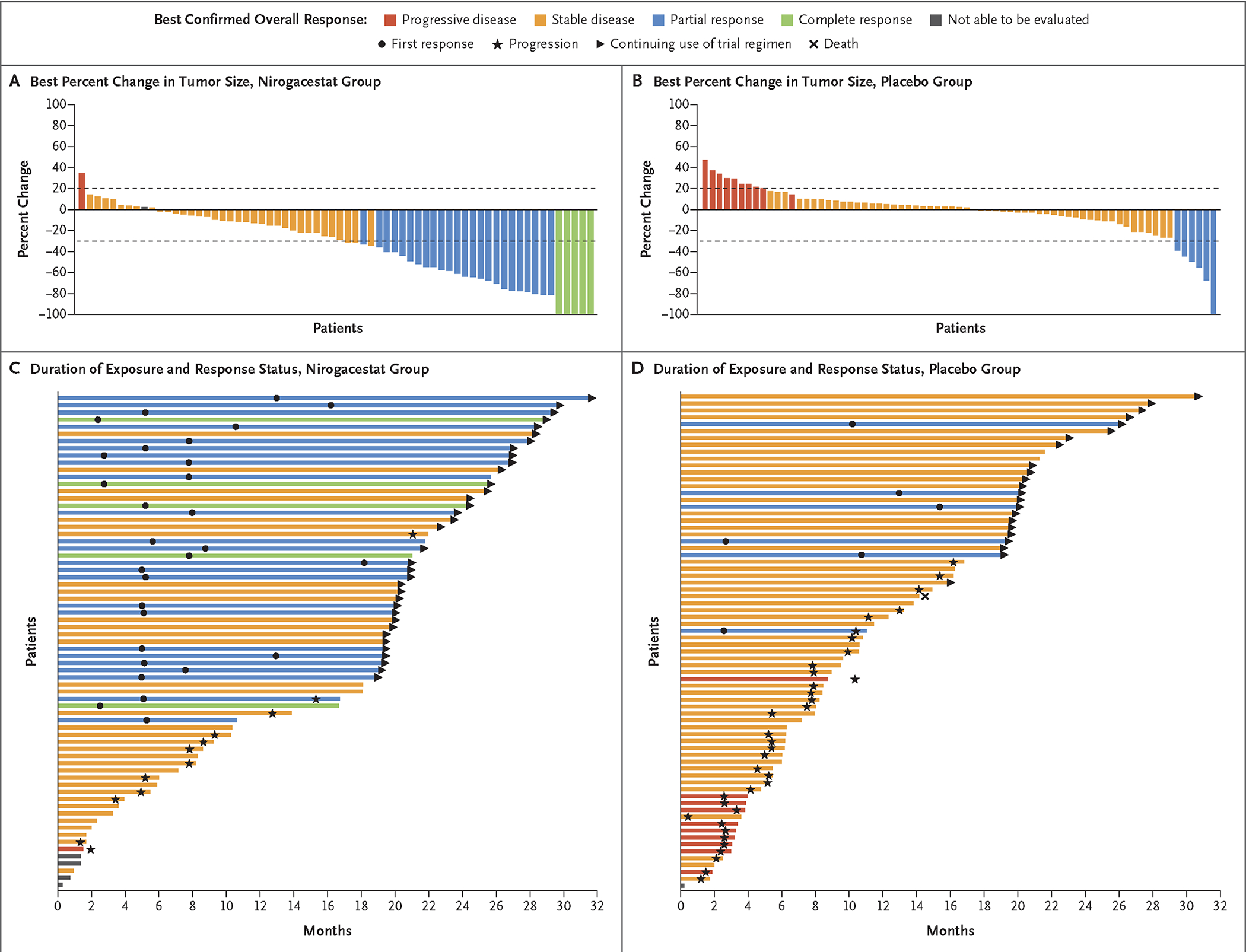

The percentage of patients with a confirmed objective response was 41% in the nirogacestat group and 8% in the placebo group (P<0.001). Complete responses were observed in 7% of the patients in the nirogacestat group and no patients in the placebo group (Fig. 2A and 2B and Table S2). The median time to a confirmed first response was 5.6 months with nirogacestat and 11.1 months with placebo. The median best percent change in target-tumor size was −27.1% (range, −100 to 37) in the nirogacestat group and 2.3% (range, −100 to 47) in the placebo group. At the time of the analysis, 28 of 29 patients (97%) who had had a response in the nirogacestat group and 5 of 6 patients (83%) who had had a response in the placebo group were still having a response (Fig. 2C and 2D and Fig. S3).

Figure 2. Change in Tumor Size and Best Overall Response.

Panels A and B show waterfall plots of the best percent change at any time point from baseline in target-tumor size per patient according to RECIST, version 1.1, through blinded independent central review in each trial group. Values for best percent change were averaged between the two independent reviewers unless a reader was selected for adjudication, in which case only the adjudicated value is presented. Panels C and D show swimmer plots of duration of exposure and response status in each trial group. Colors indicate the best overall response according to RECIST, version 1.1, through blinded independent central review.

PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOMES

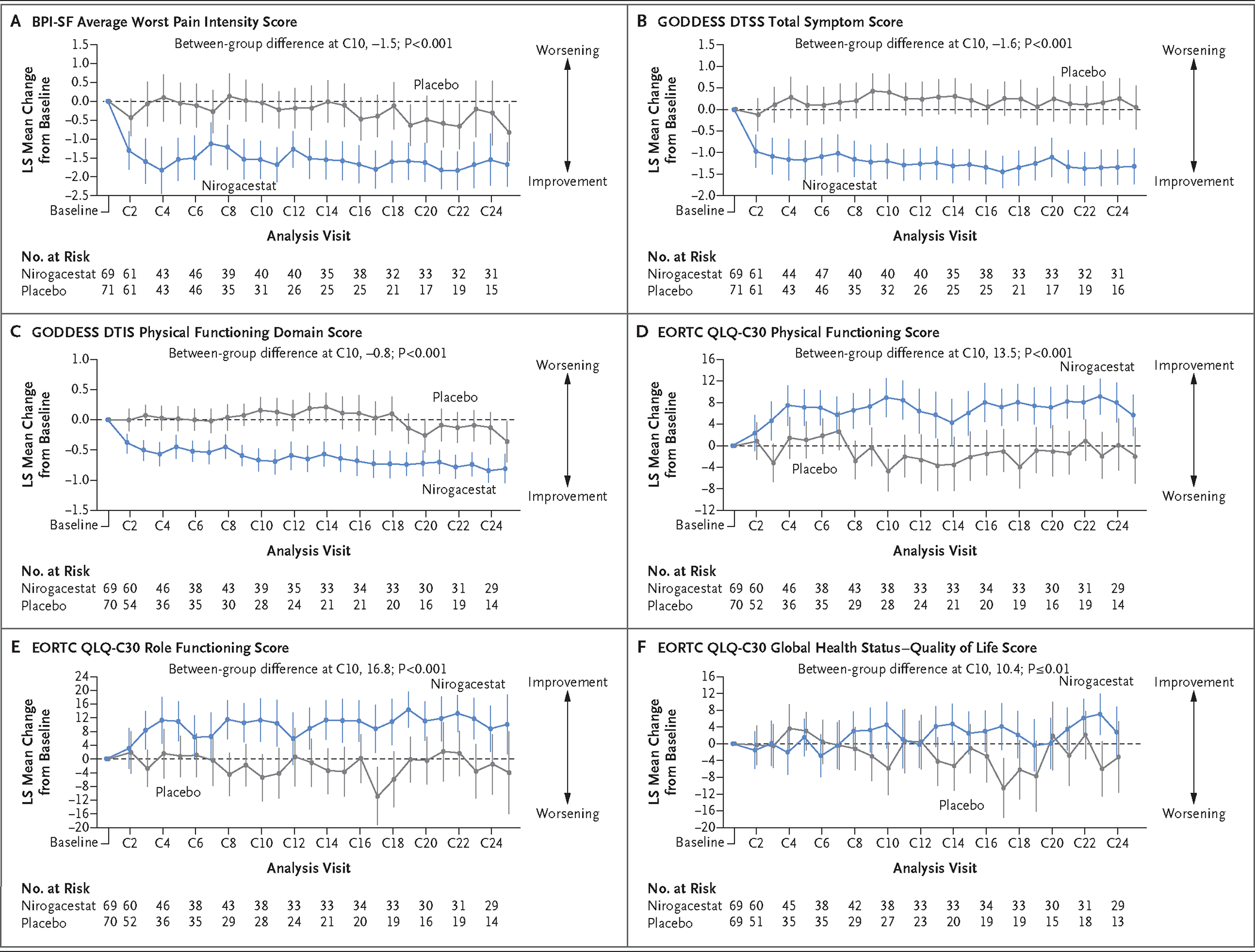

At cycle 10, nirogacestat showed significant and clinically meaningful benefits over placebo with respect to pain, disease-specific symptom severity, and disease-specific physical functioning (as measured by the BPI-SF average worst pain intensity score [P<0.001], the GODDESS DTSS total symptom score [P<0.001], and the GODDESS DTIS physical functioning domain score [P<0.001]) (Fig. 3A, 3B, and 3C); physical and role functioning (as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning score [P<0.001] and role functioning score [P<0.001]) (Fig. 3D and 3E); and overall health-related quality of life (as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status–quality of life score [P≤0.01]) (Fig. 3F). Between-group differences in most patient-reported outcomes emerged early (i.e., at cycle 2, the first post-treatment time point evaluated) and were sustained throughout the trial.

Figure 3. Patient-Reported Outcomes.

Shown are least-squares (LS) mean changes from baseline over time in patient-reported outcomes; the vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form (BPI-SF) average worst pain intensity scores (Panel A) range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse pain; scores represent a 7-day average of daily scores for worst pain. Gounder–Desmoid Tumor Research Foundation Desmoid Symptom/Impact Scale (GODDESS) Desmoid Tumor Symptom Scale (DTSS) total symptom scores (Panel B) range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating a more severe symptom burden. GODDESS Desmoid Tumor Impact Scale (DTIS) physical functioning domain scores (Panel C) range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse functioning. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire–Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) physical functioning scores (Panel D), role functioning scores (Panel E), and global health status–quality of life scores (Panel F) range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning or better quality of life. Mean (±SD) scores at baseline were as follows: BPI-SF average worst pain intensity score, 3.2±3.3 in the nirogacestat group and 3.3±3.3 in the placebo group; GODDESS DTSS total symptom score, 3.4±2.3 and 3.5±2.6, respectively; GODDESS DTIS physical functioning domain score, 2.8±1.1 and 2.7±1.2, respectively; EORTC QLQ-C30 physical functioning score, 77.5±22.4 and 77.1±22.0, respectively; EORTC QLQ-C30 role functioning score, 65.2±32.7 and 65.7±30.2, respectively; and EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status–quality of life score, 60.0±24.5 and 63.3±20.7, respectively. C denotes cycle.

EXPOSURE, SAFETY, AND ADVERSE EVENTS

A total of 141 patients received at least one dose of nirogacestat or placebo and were included in the safety assessment (69 in the nirogacestat group and 72 in the placebo group). The median duration of exposure was 20.6 months (range, 0.3 to 33.6) among the patients receiving nirogacestat and 11.4 months (range, 0.2 to 32.5) among those receiving placebo. The median relative dose intensity was 96% for nirogacestat and 100% for placebo.

The first onset of the majority of adverse events occurred within the first cycle; 95% were of grade 1 or 2. Adverse events affecting at least 20% of the patients who received nirogacestat were diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, hypophosphatemia, maculopapular rash, stomatitis, headache, dermatitis acneiform, and vomiting (Table 2). The only serious adverse event that occurred in more than 1 patient in the nirogacestat group was premature menopause (in 3 patients) (Table S3). Dose reductions due to adverse events were more frequently reported among patients receiving nirogacestat (42%) than among those receiving placebo (0%) and were attributed primarily to diarrhea, stomatitis, maculopapular rash, hypophosphatemia, hidradenitis, ovarian failure, and folliculitis. Adverse events led to discontinuation of the trial regimen in 14 patients (20%) in the nirogacestat group and 1 patient (1%) in the placebo group. The most frequent adverse events resulting in discontinuation of nirogacestat included diarrhea (in 4 patients), ovarian dysfunction (in 4), and an increased level of alanine aminotransferase (in 3).

Table 2.

Adverse Events in the Safety Population.*

| Category | Nirogacestat (N = 69) | Placebo (N = 72) |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse event, any grade — no. (%) | 69 (100) | 69 (96) |

| Advert event, grade ≥3 — no. (%) | 38 (55) | 12 (17) |

| Adverse event leading to early discontinuation of nirogacestat or placebo, any grade — no. (%) | 14 (20) | 1 (1) |

| Adverse event leading to death — no. (%) | 0 | 1 (1)† |

| Adverse events reported in ≥15% of patients in either group, any grade — no. (%) | ||

| Diarrhea | 58 (84) | 25 (35) |

| Nausea | 37 (54) | 28 (39) |

| Fatigue | 35 (51) | 26 (36) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 29 (42) | 5 (7) |

| Maculopapular rash | 22 (32) | 4 (6) |

| Stomatitis | 20 (29) | 3 (4) |

| Headache | 20 (29) | 11 (15) |

| Dermatitis acneiform | 15 (22) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 14 (20) | 14 (19) |

| Rash | 13 (19) | 5 (7) |

| Hot flush | 13 (19) | 4 (6) |

| Alopecia | 13 (19) | 1 (1) |

| Alanine aminotransferase level increased | 12 (17) | 6 (8) |

| Covid-19 | 12 (17) | 12 (17) |

| Weight gain | 11 (16) | 5 (7) |

| Cough | 11 (16) | 3 (4) |

| Abdominal pain | 11 (16) | 9 (12) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level increased | 11 (16) | 8 (11) |

| Dyspnea | 11 (16) | 4 (6) |

| Decreased appetite | 11 (16) | 8 (11) |

| Dry skin | 11 (16) | 5 (7) |

| Tumor pain | 5 (7) | 13 (18) |

| Ovarian dysfunction‡ | ||

| In the safety population — no. (%) | 27 (39) | 0 |

| In women of childbearing potential in the safety population — no./total no. (%) | 27/36 (75) | 0/37 |

Shown are adverse events that emerged or worsened from the time of the first dose of nirogacestat or placebo through 30 days after the last dose. Covid-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019.

The patient died from sepsis.

Ovarian dysfunction includes the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.0, preferred terms amenorrhea, premature menopause, menopause, and ovarian failure.

Adverse events that were frequently managed by medical intervention included diarrhea, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and skin events. Diarrhea events (of which 90% were grade 1 or 2) were most frequently managed with dose modifications, dose interruptions, and antidiarrheal agents. Hypophosphatemia and hypokalemia were primarily managed with supplementation. Skin events with nirogacestat included noninfectious events, such as maculopapular rash (in 22 patients [32%]) and hidradenitis (in 6 patients [9%]), and infectious events, including folliculitis (in 9 patients [13%]). No patients in the placebo group had folliculitis or hidradenitis. Skin disorders were most frequently managed with dose modifications, topical glucocorticoids, and antibiotics.

Ovarian dysfunction (defined by the MedDRA preferred terms of amenorrhea, premature menopause, menopause, and ovarian failure) occurred in 27 of 36 women of childbearing potential (75%) receiving nirogacestat and in 0 of 37 receiving placebo. The median time to first onset of ovarian dysfunction was 8.9 weeks, and the median duration across ovarian dysfunction events was 19.1 weeks. According to the investigators, 20 of 27 women of childbearing potential (74%) who had ovarian dysfunction events had event resolution on the basis of their assessment of symptoms, reproductive hormone values, or both (9 patients while receiving nirogacestat and 11 after stopping nirogacestat for any reason) as of the extended follow-up date of July 20, 2022. Ovarian dysfunction was unresolved in 5 of 27 women of childbearing potential (19%), all of whom continued to receive nirogacestat. Follow-up information after discontinuation of nirogacestat was not available for 2 of 27 women (7%) of childbearing potential with ovarian dysfunction. No meaningful changes in male hormonal levels or adverse events pertaining to male reproductive potential were observed.

DISCUSSION

Inhibitors of γ-secretase, initially developed for Alzheimer’s disease and later investigated as a treatment for cancer, have yet to be used in clinical practice.22,23 DeFi was a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial of nirogacestat, a γ-secretase inhibitor, in patients with desmoid tumors. In the trial, nirogacestat showed rapid and sustained improvements with respect to all primary and secondary efficacy end points. Nirogacestat treatment resulted in a 71% lower risk of disease progression or death than placebo according to blinded central review, with 41% of patients having a confirmed objective response and 7% having a complete response. Although long-term treatment with nirogacestat was shown to be feasible (median treatment duration, 20.6 months), the appropriate treatment duration is unknown.

Although multiple therapies have shown activity in desmoid tumors, there is no accepted standard of care; even patients with progressing disease often have a period of active surveillance before the initiation of treatment.13 In a phase 3 trial of sorafenib involving adults with desmoid tumors, progression-free survival was significantly longer with sorafenib than with placebo (P<0.001); however, 20% of the participants in the placebo group had an objective response, a finding that highlights the need for a placebo control in this population.29 Although sorafenib showed robust activity in desmoid tumors, it is not approved for this indication, and given the well-known safety profile of tyrosine kinase inhibitors,29–32 an effective therapy with an alternative safety profile remains a substantial unmet need.

Desmoid tumors are associated with low mortality but high morbidity.1–3,13 Given that the median age of patients with desmoid tumors is between 30 and 40 years,1,33 the clinical opportunity for improving long-term health-related quality of life in this population is substantial. Owing to the selection of an actively progressing patient population, the baseline prevalence of characteristics associated with a difficult-to-treat population was higher among patients who were enrolled in our trial than among those enrolled in other clinical trials involving patients with desmoid tumors.29–32,34 These characteristics included recurrent or refractory desmoid tumors after previous treatment (77%), multifocal tumors (41%), and uncontrolled pain (41%). Despite these characteristics, nirogacestat showed significant and clinically meaningful antitumor activity, reduced pain and symptom burden, and improved physical functioning, role functioning, and health-related quality of life in all key patient-reported outcomes evaluated.

Improvements in patient-reported outcomes were observed early and were sustained over time. The improvements seen in the desmoid tumor–specific GODDESS assessment were corroborated by two well-established general instruments (i.e., BPI-SF and EORTC QLQ-C30). Because global health status and health-related quality of life may be influenced by factors outside of disease symptoms, variability can be expected from these general scales as compared with those specific to desmoid tumor symptoms and functioning. Regardless, nirogacestat showed significant improvements in terms of the broad global health status and health-related quality of life subscale as compared with placebo.

The safety profile of nirogacestat was generally consistent with γ-secretase inhibition.35,36 Frequently reported adverse events with nirogacestat were diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, hypophosphatemia, maculopapular rash, stomatitis, headache, dermatitis acneiform, vomiting, and ovarian dysfunction (among women of childbearing potential), with 95% of all adverse events being of grade 1 or 2.

On the basis of preclinical data, the ovarian dysfunction associated with nirogacestat may be due to the disruption of Notch signaling required for ovarian follicular cycling.37 The Notch pathway is critical for the development of ovarian follicles and the granulosa cell layer. Components of the Notch pathway are abundantly expressed in preantral follicles, and inhibition of this pathway may disrupt follicle development.37 Ovarian dysfunction may produce clinical manifestations including irregular menses, amenorrhea, or vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hot flashes and night sweats).38 Laboratory findings may include increased levels of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone and decreased levels of estradiol or anti-Müllerian hormone.

Amenorrhea was a safety signal identified in our trial, given the large proportion of women of childbearing potential enrolled. Therefore, monitoring of reproductive hormones was added for all the patients, which enabled a more comprehensive characterization of these events. Previous studies of γ-secretase inhibitors may not have identified this signal owing to the enrollment of older participants.39,40 Our findings highlight the importance of prospectively evaluating reproductive function in clinical studies involving women of childbearing potential. Resolution of ovarian dysfunction occurred in the majority of women of childbearing potential who continued nirogacestat treatment (9 of 14 [64%]) and all who stopped receiving nirogacestat for any reason (excluding 2 women of childbearing potential for whom follow-up data were not available). Further evaluation of ovarian dysfunction in patients who transitioned to the DeFi open-label extension is ongoing. In addition, nirogacestat is being further evaluated in children with desmoid tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04195399), in patients with ovarian granulosa-cell tumors (NCT05348356), and across multiple trials in combination with B-cell maturation antigen therapeutic agents in patients with multiple myeloma.

In this trial involving patients with progressing desmoid tumors, nirogacestat showed significant benefits with respect to progression-free survival, objective response, pain, disease-specific symptom burden, physical functioning, role functioning, and health-related quality of life. Adverse events were mainly low-grade and transient.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the trial patients, their families, and the trial personnel; former principal investigators Victor Villalobos, Jonathan Trent, Robert Maki, Suzanne George, Michael Nathenson, and Amanda Parkes for their contributions; the principal investigators who contributed to the screening of trial patients (Christian Meyer, Mark Agulnik, James Hu, Vicki Keedy, and Jade Homsi); the members of the data monitoring committee (Timothy Cripe, Damon Reed, Stephen Skapek, and Barry Turnbull); the contributors from SpringWorks Therapeutics (Victoria Brown for clinical trial management, Anilkumar Jangili, Kendal Benza, and Vincent Amoruccio for statistical programming and biometrics support, and Jennifer Han, Ana B. Oton, Timothy Bell, David Hyslop, Amy Kranz, and Josef Witt-Doerring for strategic guidance on manuscript development); and Rhyomi Sellnow and Lauren Bragg of MedThink SciCom for medical writing and editorial assistance with an earlier version of the manuscript.

Supported by SpringWorks Therapeutics.

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Mrinal Gounder, M.D., Ravin Ratan, M.D., Thierry Alcindor, M.D., Patrick Schöffski, M.D., M.P.H., Winette T. van der Graaf, M.D., Ph.D., Breelyn A. Wilky, M.D., Richard F. Riedel, M.D., Allison Lim, Pharm.D., L. Mary Smith, Ph.D., Stephanie Moody, M.S., Steven Attia, D.O., Sant Chawla, M.D., Gina D’Amato, M.D., Noah Federman, M.D., Priscilla Merriam, M.D., Brian A. Van Tine, M.D., Ph.D., Bruno Vincenzi, M.D., Ph.D., Charlotte Benson, M.B., Ch.B., Nam Quoc Bui, M.D., Rashmi Chugh, M.D., Gabriel Tinoco, M.D., John Charlson, M.D., Palma Dileo, M.D., Lee Hartner, M.D., Lore Lapeire, M.D., Ph.D., Filomena Mazzeo, M.D., Emanuela Palmerini, M.D., Ph.D., Peter Reichardt, M.D., Silvia Stacchiotti, M.D., Howard H. Bailey, M.D., Melissa A. Burgess, M.D., Gregory M. Cote, M.D., Ph.D., Lara E. Davis, M.D., Hari Deshpande, M.D., Hans Gelderblom, M.D., Ph.D., Giovanni Grignani, M.D., Elizabeth Loggers, M.D., Ph.D., Tony Philip, M.D., Joseph G. Pressey, M.D., Shivaani Kummar, M.D., and Bernd Kasper, M.D., Ph.D.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

M. Gounder, Sarcoma Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

R. Ratan, Department of Sarcoma Medical Oncology, Division of Cancer Medicine, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Belgium

T. Alcindor, Department of Oncology, McGill University, Montreal, Belgium

P. Schöffski, Department of General Medical Oncology, University Hospitals Leuven, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

W.T. van der Graaf, Department of Medical Oncology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

B.A. Wilky, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Cancer Center, Aurora, Durham, NC

R.F. Riedel, Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC

A. Lim, SpringWorks Therapeutics, Stamford, Connecticut

L.M. Smith, SpringWorks Therapeutics, Stamford, Connecticut

S. Moody, PharPoint Research, Durham, NC

S. Attia, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida

S. Chawla, Sarcoma Oncology Center, Santa Monica, California

G. D’Amato, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami Health System, Miami, Florida

N. Federman, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California

P. Merriam, Sarcoma and Bone Cancer Treatment Center, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston

B.A. Van Tine, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Rome

B. Vincenzi, Department of Medicine and Surgery, Università Campus Bio-Medico di Roma, and Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Campus Bio-Medico, Rome

C. Benson, Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London

N.Q. Bui, Division of Oncology, Stanford Cancer Institute, Stanford, California

R. Chugh, University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center, Ann Arbor

G. Tinoco, Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus

J. Charlson, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

P. Dileo, Department of Medical Oncology, University College London Hospital Foundation Trust, London

L. Hartner, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

L. Lapeire, Department of Medical Oncology, Ghent University Hospital, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

F. Mazzeo, King Albert II Cancer Institute, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Catholic University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

E. Palmerini, Osteoncology, Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcoma, and Innovative Therapy Unit, IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli, Bologna, Italy

P. Reichardt, Sarcoma Center Berlin–Brandenburg, Helios Klinikum Berlin-Buch, Berlin, Germany

S. Stacchiotti, Department of Medical Oncology, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy

H.H. Bailey, University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, Madison

M.A. Burgess, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh

G.M. Cote, Henri and Belinda Termeer Center for Targeted Therapies, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, Boston

L.E. Davis, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland

H. Deshpande, Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale Cancer Center, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

H. Gelderblom, Department of Medical Oncology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

G. Grignani, Medical Oncology, Candiolo Cancer Institute FPO-IRCCS, Candiolo, Italy

E. Loggers, Division of Medical Oncology, University of Washington, the Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, Seattle

T. Philip, Northwell Health Cancer Institute, New Hyde Park, New York

J.G. Pressey, Cancer and Blood Diseases Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati

S. Kummar, Knight Cancer Institute, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland

B. Kasper, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim University Medical Center, Mannheim Cancer Center, Sarcoma Unit, Mannheim, Germany

REFERENCES

- 1.Penel N, Chibon F, Salas S. Adult desmoid tumors: biology, management and ongoing trials. Curr Opin Oncol 2017;29:268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gounder MM, Maddux L, Paty J, Atkinson TM. Prospective development of a patient-reported outcomes instrument for desmoid tumors or aggressive fibromatosis. Cancer 2020;126:531–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasper B, Baumgarten C, Garcia J, et al. An update on the management of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatosis: a European Consensus Initiative between Sarcoma PAtients EuroNet (SPAEN) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group (STBSG). Ann Oncol 2017;28:2399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Constantinidou A, Scurr M, Judson I, Litchman C. Clinical presentation of desmoid tumors. In: Litchman C, ed. Desmoid tumors. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Dordrecht, 2012:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schut A-RW, Lidington E, Timbergen MJM, et al. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (DTF-QoL) for patients with desmoid-type fibromatosis. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husson O, Younger E, Dunlop A, et al. Desmoid fibromatosis through the patients’ eyes: time to change the focus and organisation of care? Support Care Cancer 2019;27:965–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuomo P, Scoccianti G, Schiavo A, et al. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumor fibromatosis: a multicenter EMSOS study. BMC Cancer 2021;21:437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim Y, Rosario MS, Cho HS, Han I. Factors associated with disease stabilization of desmoid-type fibromatosis. Clin Orthop Surg 2020;12:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gronchi A, Raut CP. Optimal approach to sporadic desmoid tumors:from radical surgery to observation. Time for a consensus? Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3995–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoeckle E, Coindre JM, Longy M, et al. A critical analysis of treatment strategies in desmoid tumours: a review of a series of 106 cases. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonvalot S, Ternès N, Fiore M, et al. Spontaneous regression of primary abdominal wall desmoid tumors: more common than previously thought. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:4096–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedel RF, Agulnik M. Evolving strategies for management of desmoid tumor. Cancer 2022;128:3027–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desmoid Tumor Working Group. The management of desmoid tumours: a joint global consensus-based guideline approach for adult and paediatric patients. Eur J Cancer 2020;127:96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCCN guidelines for patients:soft tissue sarcoma. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2020. (https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/sarcoma-patient.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y, Huang Y, Zhou M, Ying X, Hu X. High-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for intra-abdominal desmoid tumors: a report of four cases. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2016;43:279–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salas S, Dufresne A, Bui B, et al. Prognostic factors influencing progression-free survival determined from a series of sporadic desmoid tumors: a wait-and-see policy according to tumor presentation. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsagozis P, Stevenson JD, Grimer R, Carter S. Outcome of surgery for primary and recurrent desmoid-type fibromatosis. A retrospective case series of 174 patients. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;17:14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federman N Molecular pathogenesis of desmoid tumor and the role of γ-secretase inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol 2022;6:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carothers AM, Rizvi H, Hasson RM, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell mutations and wound healing contribute to the etiology of desmoid tumors. Cancer Res 2012;72:346–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shang H, Braggio D, Lee Y-J, et al. Targeting the Notch pathway: a potential therapeutic approach for desmoid tumors. Cancer 2015;121:4088–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siebel C, Lendahl U. Notch signaling in development, tissue homeostasis, and disease. Physiol Rev 2017;97:1235–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golde TE, Koo EH, Felsenstein KM, Osborne BA, Miele L. γ-Secretase inhibitors and modulators. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1828:2898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takebe N, Nguyen D, Yang SX. Targeting notch signaling pathway in cancer: clinical development advances and challenges. Pharmacol Ther 2014;141:140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gounder MM. Notch inhibition in desmoids: “Sure it works in practice, but does it work in theory?” Cancer 2015;121:3933–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei P, Walls M, Qiu M, et al. Evaluation of selective gamma-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 for its antitumor efficacy and gastrointestinal safety to guide optimal clinical trial design. Mol Cancer Ther 2010;9:1618–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messersmith WA, Shapiro GI, Cleary JM, et al. A Phase I, dose-finding study in patients with advanced solid malignancies of the oral γ-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:60–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villalobos VM, Hall F, Jimeno A, et al. Long-term follow-up of desmoid fibromatosis treated with PF-03084014, an oral gamma secretase inhibitor. Ann Surg Oncol 2018;25:768–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kummar S, O’Sullivan Coyne G, Do KT, et al. Clinical activity of the γ-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 in adults with desmoid tumors (aggressive fibromatosis). J Clin Oncol 2017;35:1561–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA, et al. Sorafenib for advanced and refractory desmoid tumors. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2417–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toulmonde M, Pulido M, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Pazopanib or methotrexate-vinblastine combination chemotherapy in adult patients with progressive desmoid tumours (DESMOPAZ): a non-comparative, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1263–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chugh R, Wathen JK, Patel SR, et al. Efficacy of imatinib in aggressive fibromatosis: results of a phase II multicenter Sarcoma Alliance for Research through Collaboration (SARC) trial. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16:4884–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penel N, Le Cesne A, Bui BN, et al. Imatinib for progressive and recurrent aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumors): an FNCLCC/French Sarcoma Group phase II trial with a long-term follow-up. Ann Oncol 2011;22:452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anneberg M, Svane HML, Fryzek J, et al. The epidemiology of desmoid tumors in Denmark. Cancer Epidemiol 2022;77:102114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li S, Fan Z, Fang Z, et al. Efficacy of vinorelbine combined with low-dose methotrexate for treatment of inoperable desmoid tumor and prognostic factor analysis. Chin J Cancer Res 2017;29:455–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coric V, van Dyck CH, Salloway S, et al. Safety and tolerability of the γ-secretase inhibitor avagacestat in a phase 2 study of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henley DB, Sundell KL, Sethuraman G, Dowsett SA, May PC. Safety profile of semagacestat, a gamma-secretase inhibitor: IDENTITY trial findings. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:2021–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanorny DA, Mayo KE. The role of Notch signaling in the mammalian ovary. Reproduction 2017;153:R187–R204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thurston RC, Joffe H. Vasomotor symptoms and menopause: findings from the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2011;38:489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahebjam S, Bedard PL, Castonguay V, et al. A phase I study of the combination of ro4929097 and cediranib in patients with advanced solid tumours (PJC-004/NCI 8503). Br J Cancer 2013;109:943–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schott AF, Landis MD, Dontu G, et al. Preclinical and clinical studies of gamma secretase inhibitors with docetaxel on human breast tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:1512–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.