The crystal structures of methylene and ethylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) are reported, which represent the first crystallographic characterization of a geminal and vicinal bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) ester.

Keywords: crystal structure, bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate), geminal ditriflate, vicinal ditriflate, sensitive oil

Abstract

Geminal and vicinal bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) esters are highly reactive alkylene synthons used as potent electrophiles in the macrocyclization of imidazoles and the transformation of bypyridines to diquat derivatives via nucleophilic substitution reactions. Herein we report the crystal structures of methylene (C3H2F6O6S2) and ethylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (C4H4F6O6S2), the first examples of a geminal and vicinal bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) ester characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD). With melting points slightly below ambient temperature, both reported bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate)s are air- and moisture-sensitive oils and were crystallized at 277 K to afford two-component non-merohedrally twinned crystals. The dominant interactions present in both compounds are non-classical C—H⋯O hydrogen bonds and intermolecular C—F⋯F—C interactions between trifluoromethyl groups. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) calculations by DFT-D3 helped to quantify the polarity between O⋯H and F⋯F contacts to rationalize the self-sorting of both bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) esters in polar (non-fluorous) and non-polar (fluorous) domains within the crystal structure.

Introduction

Trifluoromethanesulfonate (triflate) is an important functional group in organic chemistry owing to its strong electron-withdrawing nature (Howells & McCown, 1977 ▸; Hendrickson et al., 1977 ▸). It is an excellent leaving group used in many organic transformations, such as nucleophilic substitutions, due to the extreme stability of the liberated triflate anion (OTf−). Thus, the derived triflyl esters (R–OTf) are potent electrophiles, representing a halogen-free alternative to alkyl halides in nucleophilic substitution reactions.

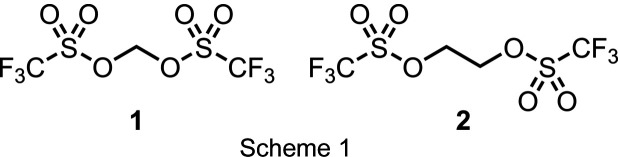

Pushing the reactivity of these compounds to an extreme, two triflate groups can be attached to the same carbon to form geminal bis(triflate) esters with the general formula TfO–CR2–OTf (Martínez et al., 1979 ▸, 1987 ▸). Among other landmark examples, the parent compound methylene bis(triflate) (1, R = H) had already been reported in 1980 (Katsuhara & DesMarteau, 1980 ▸) but has not been used in chemical synthesis until several decades later. As a highly reactive C1 synthon, the electrophilicity of 1 was eventually harnessed to construct large cyclophanes via nucleophilic substitution reactions (Anneser et al., 2015 ▸), particularly in cases where bis(imidazoles) were macrocyclized to methylene-bridged tetra(imidazolium) salts (Altmann et al., 2015 ▸, 2016 ▸; Bernd et al., 2020 ▸).

Similarly, the ethylene-bridged bis(triflate) ester TfO–(CH2)2–OTf (2) has been commonly used as a bis-alkylating reagent (C2 synthon), among others, for the transformation of bipyridines to diquat derivatives (Coe et al., 2006 ▸) and for the synthesis of ethylene-bridged metal complexes (Lindner et al., 1990 ▸) or η2-olefin metal complexes (Lindner et al., 1985 ▸).

Investigating the structure–property relationship of geminal and vicinal bis(sulfonate) esters, such as compounds 1 and 2, respectively, is imperative to gain a better understanding of their reactivity. In this regard, a structural comparison of similar alkylene bis(mesylates) used as DNA crosslinking agents has been reported, which includes the parent compound MsO–(CH2)2–OMs (3, Ms = mesyl or methanesulfonyl) (McKenna et al., 1989 ▸). So far, this study has been complemented by the structural characterizations of only a few other vicinal bis(mesylate) and bis(tosylate) derivatives, such as TsO–(CH2)2–OTs (4, Ts = tosyl or toluenesulfonyl) (Groth et al., 1985 ▸), and a handful of geminal bis(tosylates) (Kamal et al., 2020 ▸).

To date, however, there are no reports on the molecular structures of geminal or vicinal bis(triflate) esters, such as the title compounds 1 and 2 (see Scheme 1). Aiming to study the structure–reactivity relationship of these alkylene sources, we synthesized both compounds and characterized them in the solid state by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD).

Experimental

Synthesis and crystallization

Sulfonate esters 1 and 2 were prepared according to established procedures. Methylene bis(triflate) (1) was synthesized by heating an equimolar suspension of triflic anhydride and paraformaldehyde to 353 K, causing the liberation of formaldehyde, which was further reacted with the anhydride at the same temperature for 16 h. Following the evaporation of excess triflic anhydride in vacuo, the crude product was passed over a short plug of silica with dichloromethane as the eluent. After removal of all volatiles at 293 K under reduced pressure, analytically pure 1 was obtained as a colourless-to-brown oil. The yields of this reaction typically range between 15 and 20%, which is consistent with previous reports (Anneser et al., 2015 ▸).

There are several approaches for the preparation of ethylene bis(triflate) (2), e.g. the straightforward transmetalation of ethylene dibromide with AgOTf (Shackelford et al., 1985 ▸). However, for the purpose of this study, the reaction of ethylene glycol with triflic anhydride under basic conditions was chosen as the preferred method because the diol is readily available and inexpensive, and the desired product is usually obtained in close to quantitative yields (Kuroboshi et al., 2015 ▸). To equimolar amounts of triflic anhydride and pyridine in dichloromethane was added half an equivalent of ethylene glycol at 273 K. The reaction mixture was stirred at the same temperature for 45 min, filtered and washed several times with water. The organic layer was dried over sodium sulfate, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was filtered over a short plug of silica with dichloromethane as the eluent. All volatiles were subsequently removed at 293 K under reduced pressure to afford analytically pure 2 as a colourless oil (81% yield).

Bis(triflates) 1 and 2 are air- and water-sensitive liquids at ambient temperature, with melting points between 278 and 288 K (Lindner et al., 1981 ▸; Anneser et al., 2015 ▸). Single crystals were grown by allowing the compounds to solidify slowly over the course of several hours at a temperature of 277 K. To prevent the obtained crystals from melting immediately during picking, the tools used in the process were cooled by repeatedly submerging them in a Dewar flask filled with liquid nitrogen. Additionally, a piece of dry ice was placed on the microscope slide to delay the melting of the specimen on the glass. The selected crystals were then mounted on top of a Kapton micro sample holder (MicroMount) coated with perfluorinated ether and rapidly transferred to the diffractometer.

Refinement

Data collection and structure refinement details are summarized in Table 1 ▸. As implemented in APEX4 (Bruker, 2022 ▸), the non-merohedral twinning of 1 and 2 was addressed by integration of the diffraction data using two orientation matrices in SAINT (Bruker, 2019 ▸), followed by scaling and absorption correction with TWINABS (Bruker, 2012 ▸). The structures were solved by SHELXT (Sheldrick, 2015a ▸) and refined against the respective HKLF5 files using SHELXL (Sheldrick, 2015b ▸) in conjunction with ShelXle (Hübschle et al., 2011 ▸). All non-H atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. H atoms could be located in difference Fourier maps, but for the refinement were positioned geometrically and refined using a riding model, with C—H = 0.99 Å and Uiso(H) = 1.2Ueq(C).

Table 1. Experimental details.

Experiments were carried out at 100 K with Mo Kα radiation using a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer. Absorption was corrected for by multi-scan methods (TWINABS; Bruker, 2012 ▸). H-atom parameters were constrained.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal data | ||

| Chemical formula | C3H2F6O6S2 | C4H4F6O6S2 |

| M r | 312.17 | 326.19 |

| Crystal system, space group | Monoclinic, P21 | Triclinic, P

|

| a, b, c (Å) | 8.9822 (12), 4.9413 (6), 10.9400 (14) | 10.036 (4), 10.664 (3), 11.276 (4) |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 102.406 (5), 90 | 83.540 (9), 64.178 (9), 89.593 (9) |

| V (Å3) | 474.22 (11) | 1078.2 (6) |

| Z | 2 | 4 |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.68 | 0.60 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.35 × 0.32 × 0.06 | 0.16 × 0.09 × 0.01 |

| Data collection | ||

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.540, 0.746 | 0.564, 0.745 |

| No. of measured, independent and observed [I > 2σ(I)] reflections | 2295, 2295, 2254 | 4339, 4339, 3403 |

| R int | 0.044 | 0.079 |

| (sin θ/λ)max (Å−1) | 0.667 | 0.625 |

| Refinement | ||

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)], wR(F2), S | 0.027, 0.072, 1.05 | 0.066, 0.166, 1.07 |

| No. of reflections | 2295 | 4339 |

| No. of parameters | 155 | 326 |

| No. of restraints | 1 | 0 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin (e Å−3) | 0.41, −0.47 | 0.60, −0.55 |

| Absolute structure | Flack x determined using 959 quotients [(I+) − (I−)]/[(I+) + (I−)] (Parsons et al., 2013 ▸) | – |

| Absolute structure parameter | 0.12 (4) | – |

DFT calculations

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed with the ORCA quantum chemistry package (Version 5.0.4; Neese, 2012 ▸, 2022 ▸) using the PBE0 exchange-correlation functional (Adamo & Barone, 1999 ▸) and the def2-TZVP triple-ξ valence basis set (Weigend & Ahlrichs, 2005 ▸), as implemented in ORCA. Tighter than normal convergence criteria for SCF calculations (TightSCF) and geometry optimizations (TightOPT) were employed. Grimme’s atom-pairwise dispersion correction with the Becke–Johnson damping scheme (D3BJ) was applied to account for dispersion interactions (Grimme et al., 2010 ▸, 2011 ▸). Geometries were optimized in the gas phase without symmetry constraints. The starting geometries were derived from the SC-XRD structures of 1 and 2. Frequency analysis at the same level of theory as the geometry optimizations confirmed that the calculations had converged to an energetic minimum. To calculate the molecular electrostatic potentials (MEPs), the total SCF density file obtained after a PBE0/def2-TZVP single-point calculation was first converted to a Gaussian cube file using the orca_plot module implemented in the ORCA package. The MEP was then calculated using the orca-vpot module and exported in Gaussian cube format. With both cube files in hand, the total SCF density was plotted and the MEP was mapped as a colour onto the isosurface in Molekel (Version 4.3; Varetto, 2002 ▸).

Results and discussion

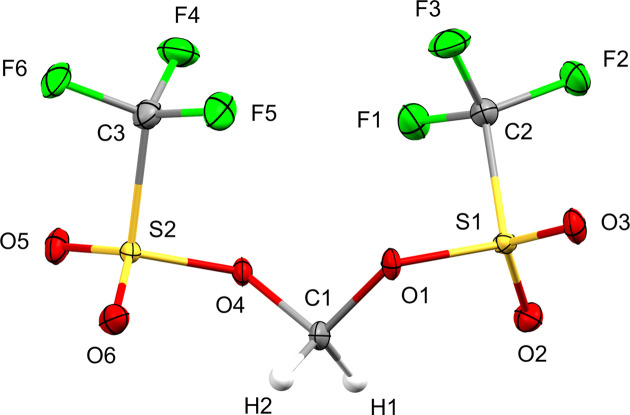

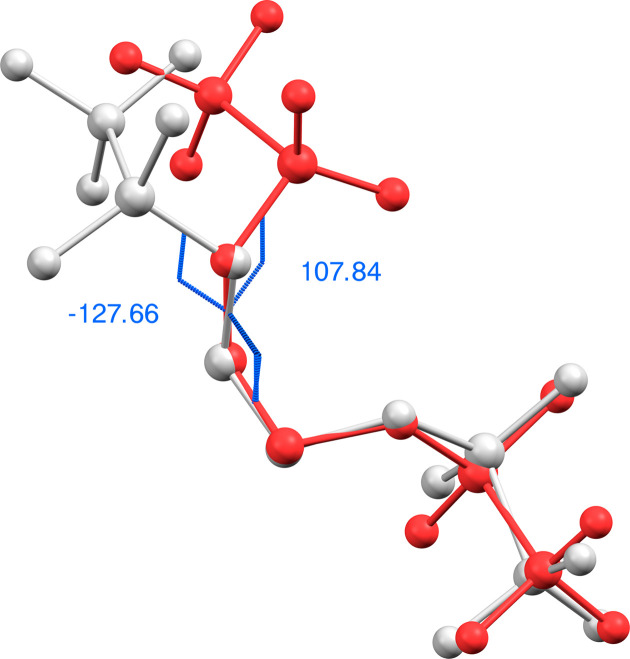

Sulfonate esters 1 and 2 both crystallized as two-component non-merohedral twins, and their asymmetric units contain one and two crystallographically independent molecules, respectively (Figs. 1 ▸ and 2 ▸). Methylene bis(triflate) (1) was found to crystallize in the monoclinic space group P21 (No. 4, Z = 2), and the fractional contribution of the minor twin component was refined to 29% in the final model. Ethylene bis(triflate) (2) crystallized in the triclinic space group P (No. 2, Z = 4) with a 37% contribution of the minor twin component. While both triflic esters are achiral in solution, as indicated by a single 1H NMR resonance for the CH2 protons (Salomon & Salomon, 1979 ▸; Katsuhara & DesMarteau, 1980 ▸), bis(triflate) 1 appears to be conformationally locked in the solid state and consequently crystallizes in the Sohncke space group P21. Since sulfur is the heaviest atom of the molecule and molybdenum radiation was used in the diffraction experiment, the absolute structure could only be determined with low accuracy. This is reflected by a Flack parameter of 0.12 with a comparably large standard uncertainty (Flack, 1983 ▸; Parsons et al., 2013 ▸). In contrast to bis(triflate) 1, ethylene derivative 2 crystallizes in a centrosymmetric space group (P

(No. 2, Z = 4) with a 37% contribution of the minor twin component. While both triflic esters are achiral in solution, as indicated by a single 1H NMR resonance for the CH2 protons (Salomon & Salomon, 1979 ▸; Katsuhara & DesMarteau, 1980 ▸), bis(triflate) 1 appears to be conformationally locked in the solid state and consequently crystallizes in the Sohncke space group P21. Since sulfur is the heaviest atom of the molecule and molybdenum radiation was used in the diffraction experiment, the absolute structure could only be determined with low accuracy. This is reflected by a Flack parameter of 0.12 with a comparably large standard uncertainty (Flack, 1983 ▸; Parsons et al., 2013 ▸). In contrast to bis(triflate) 1, ethylene derivative 2 crystallizes in a centrosymmetric space group (P ) and the asymmetric unit contains two symmetry-independent conformers of the molecule, which differ mainly in the relative orientation of a triflate group, as expressed by different C—C—O—S torsion angles (Fig. 3 ▸). A comparison of the bond distances of both esters reveals almost identical values for chemically equivalent C—F, C—S and terminal S—O bonds, while the average C—O distance is slightly shorter in 1 (1.434 Å) compared to 2 (1.481 Å). In contrast, the mean bond length of the adjacent S—O bond is elongated in 1 (1.573 Å) versus2 (1.547 Å).

) and the asymmetric unit contains two symmetry-independent conformers of the molecule, which differ mainly in the relative orientation of a triflate group, as expressed by different C—C—O—S torsion angles (Fig. 3 ▸). A comparison of the bond distances of both esters reveals almost identical values for chemically equivalent C—F, C—S and terminal S—O bonds, while the average C—O distance is slightly shorter in 1 (1.434 Å) compared to 2 (1.481 Å). In contrast, the mean bond length of the adjacent S—O bond is elongated in 1 (1.573 Å) versus2 (1.547 Å).

Figure 1.

View of methylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (1) with the atom-numbering scheme. Displacement ellipsoids for non-H atoms are drawn at the 30% probability level.

Figure 2.

View of both symmetry-independent conformers of ethylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (2) with the atom-numbering scheme. Displacement ellipsoids for non-H atoms are drawn at the 30% probability level.

Figure 3.

Overlay of the two symmetry-independent conformers of 2, highlighting the different relative orientations of a trifluoromethanesulfonate group as quantified by different C—C—O—S torsion angles. For clarity, the conformers are drawn in ball-and-stick representation in red and grey, respectively.

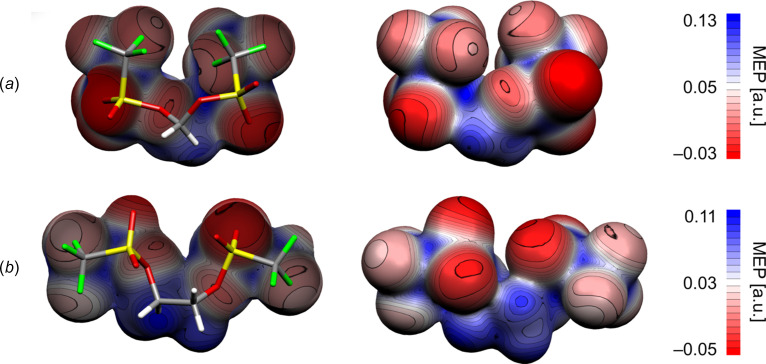

The packing of bis(triflates) 1 and 2 is primarily influenced by non-classical C—H⋯O hydrogen bonds between methylene and sulfonate groups, along with intermolecular C—F⋯F—C interactions between trifluoromethyl residues closer than the sum of the van der Waals radii (Haynes, 2015 ▸) (Tables 2 ▸–5 ▸ ▸ ▸). This interaction pattern results in the formation of two-dimensional fluorous and non-fluorous domains in the crystal packing of 1 and 2 (Figs. 4 ▸ and 5 ▸). Considering this emergence of polar and non-polar domains, we aimed to quantify the influence of differently polarized regions within both structures on the overall solid-state arrangement of the bis(triflates). Therefore, we calculated the molecular electrostatic potentials (MEPs) of 1 and 2 based on the optimized geometries of the respective monomers using DFT-D3 in the gas phase (Fig. 6 ▸). As expected, in both cases, the triflate O atoms are the most negatively charged, followed by the F atoms of the CF3 groups. In stark contrast, the CH2 fragments of methylene and ethylene bis(triflate) exhibit a high positive charge, which is consistent with their experimentally observed reactivity as strong electrophiles. Along this line, hydrogen-bonding interactions occur only between highly charged parts of both bis(triflates), namely, positively polarized alkylene H and negatively polarized sulfonate O atoms. The trifluoromethyl groups, with a lower C—F bond polarization, do not participate in hydrogen bonding. Instead, they establish fluorous domains whose arrangement in the crystal is governed by the orientation of the CF3 groups within the monomers. In methylene bis(triflate) (1), these groups align in a shared direction, whereas in ethylene bis(triflate) (2), they assume opposite orientations in the molecule. The emerging regions of different polarity within the molecules are thus caused by the observed self-sorting of 1 and 2 into highly polar and nonpolar domains within the crystal structure.

Table 2. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for 1.

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1—H1⋯O2 | 0.99 | 2.32 | 2.803 (6) | 109 |

| C1—H2⋯O6 | 0.99 | 2.29 | 2.802 (6) | 111 |

| C1—H1⋯O3iii | 0.99 | 2.51 | 3.416 (5) | 152 |

| C1—H2⋯O5iv | 0.99 | 2.56 | 3.430 (5) | 147 |

Symmetry codes: (iii)  ; (iv)

; (iv)  .

.

Table 3. Selected interatomic distances (Å) for 1.

| F3⋯F6i | 2.894 (5) | F4⋯F5i | 2.957 (3) |

| F1⋯F5ii | 2.933 (4) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Table 4. Hydrogen-bond geometry (Å, °) for 2.

| D—H⋯A | D—H | H⋯A | D⋯A | D—H⋯A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2—H2B⋯O8i | 0.99 | 2.62 | 3.60 (1) | 172 |

| C3—H3A⋯O1iii | 0.99 | 2.60 | 2.984 (9) | 103 |

| C3—H3B⋯O1iii | 0.99 | 2.59 | 2.984 (9) | 104 |

| C3—H3A⋯O8iv | 0.99 | 2.59 | 3.579 (8) | 175 |

| C6—H6A⋯O6v | 0.99 | 2.34 | 3.092 (8) | 132 |

| C6—H6A⋯O11vi | 0.99 | 2.47 | 3.034 (8) | 116 |

| C6—H6B⋯O2vii | 0.99 | 2.45 | 3.210 (8) | 133 |

| C7—H7A⋯O5vii | 0.99 | 2.49 | 3.365 (8) | 147 |

| C7—H7B⋯O7viii | 0.99 | 2.70 | 3.525 (7) | 142 |

| C7—H7B⋯O2iv | 0.99 | 2.54 | 3.349 (9) | 139 |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (iii)

; (iii)  ; (iv)

; (iv)  ; (v)

; (v)  ; (vi)

; (vi)  ; (vii)

; (vii)  ; (viii)

; (viii)  .

.

Table 5. Selected interatomic distances (Å) for 2.

| F5⋯F7 | 2.823 (7) | F3⋯F9ii | 2.954 (5) |

| F7⋯F12i | 2.951 (7) |

Symmetry codes: (i)  ; (ii)

; (ii)  .

.

Figure 4.

Packing of methylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (1), showing alternating two-dimensional layers of fluorous and non-fluorous domains along the c axis. The share of these domains of different polarity is indicated by the distances dn and dp, respectively.

Figure 5.

Packing of ethylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (2), showing alternating two-dimensional layers of fluorous and non-fluorous domains along the c axis. The share of these domains of different polarity is indicated by the distances dn and dp, respectively.

Figure 6.

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) projected onto the total electron-density surface of (a) methylene (1) and (b) ethylene bis(trifluoromethanesulfonate) (2). Geometries are optimized by DFT-D3 at the PBE0/def2-TZVP level of theory and MEPs are shown at 0.0062 a.u. electron density.

To quantify the share of these alternating domains within the crystal lattice of 1 and 2, alternating planes parallel to the ab plane were defined by (i) all trifluoromethyl C atoms or (ii) all S atoms of each crystallographically independent molecule contained in the unit cell of both structures. Consequently, the separation of polar and non-polar regions was estimated by calculating the distance between two adjacent planes defined by the S atoms (dp) or C atoms (dn) for each crystallographically independent molecule (cf. Figs. 4 ▸ and 5 ▸). For compound 2, the final dp and dn values were defined as the average of the individual values of each conformer in the asymmetric unit. For a more detailed definition of the interplanar distances dp and dn, see Fig. S1 in the supporting information. In both structures, the polar region was estimated to be larger than the non-polar (compound 1: dp ≃ 3.8 Å, dn ≃ 3.5 Å; compound 2: dp ≃ 3.7 Å, dn ≃ 2.8 Å). Interestingly, the determined share of the polar domain in 2 is slightly smaller than in 1, even though, compared to methylene bis(triflate) (1), ethylene congener 2 contains an additional CH2 group acting as a hydrogen-bond donor. Further, the somewhat smaller (polar and non-polar) domain sizes of 2versus1 suggest tighter packing of ethylene bis(triflate) in general. As an overarching trend, this rough estimation of domain size also indicates that roughly the same share can be attributed to the non-fluorous and fluorous regions in both bis(triflate) structures.

Conclusion

The first comprehensive structural analysis of a geminal and vicinal bis(triflate) ester, specifically methylene (1) and ethylene bis(triflate) (2), is presented. Both compounds are air- and moisture-sensitive oils under ambient conditions and at low temperature crystallized as non-merohedral two-component twins. The crystal structures reveal the presence of non-classical C—H⋯O hydrogen bonds and intermolecular C—F⋯F—C interactions, which govern the packing of the compounds in the solid state. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) calculations of monomers 1 and 2 based on DFT-D3 showed that these interactions are driven by the high polarity of the O⋯H contacts and the low polarity of the halogen–halogen contacts, respectively. As a result, bis(triflates) 1 and 2 self-sort in polar (non-fluorous) and non-polar (fluorous) domains of roughly the same relative size within the crystal lattice.

Supplementary Material

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, 2, 1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj3019sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) 1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup4.cdx

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup6.cml

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) 2. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup3.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup5.cdx

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup6.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup7.cml

Packing of the title compounds. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj3019sup8.pdf

Acknowledgments

This work was financed by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation). TP thanks the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes for a PhD fellowship and associated funding. All authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI Sachkostenzuschuss) and the Technical University of Munich (Catalysis Research Center & Graduate School) for financial support. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes grant to Thomas Pickl; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant SPP 1928; Fonds der Chemischen Industrie .

References

- Adamo, C. & Barone, V. (1999). J. Chem. Phys.110, 6158–6170.

- Allen, F. H., Johnson, O., Shields, G. P., Smith, B. R. & Towler, M. (2004). J. Appl. Cryst.37, 335–338.

- Altmann, P. J., Jandl, C. & Pöthig, A. (2015). Dalton Trans.44, 11278–11281. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Altmann, P. J., Weiss, D. T., Jandl, C. & Kühn, F. E. (2016). Chem. Asian J.11, 1597–1605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anneser, M. R., Haslinger, S., Pöthig, A., Cokoja, M., Basset, J.-M. & Kühn, F. E. (2015). Inorg. Chem.54, 3797–3804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bernd, M. A., Dyckhoff, F., Hofmann, B. J., Böth, A. D., Schlagintweit, J. F., Oberkofler, J., Reich, R. M. & Kühn, F. E. (2020). J. Catal.391, 548–561.

- Bruker (2012). TWINABS. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2019). SAINT. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Bruker (2022). APEX4. Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

- Coe, B. J., Curati, N. R. M. & Fitzgerald, E. C. (2006). Synthesis, pp. 146–150.

- Flack, H. D. (1983). Acta Cryst. A39, 876–881.

- Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. (2010). J. Chem. Phys.132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. (2011). J. Comput. Chem.32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Groth, P., Fjellvåg, H., Lehmann, M. S., Tammenmaa, M. & Volden, H. V. (1985). Acta Chem. Scand. A, 39, 587–591.

- Haynes, W. M. (2015). In Chemistry and Physics, 96th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Hendrickson, J. B., Sternbach, D. D. & Bair, K. W. (1977). Acc. Chem. Res.10, 306–312.

- Howells, R. D. & McCown, J. D. (1977). Chem. Rev.77, 69–92.

- Hübschle, C. B., Sheldrick, G. M. & Dittrich, B. (2011). J. Appl. Cryst.44, 1281–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kamal, R., Kumar, V., Kumar, R., Saini, S. & Kumar, R. (2020). Synlett, 31, 959–964.

- Katsuhara, Y. & DesMarteau, D. D. (1980). J. Fluorine Chem.16, 257–263.

- Kratzert, D. (2023). FinalCif, https://dkratzert.de/finalcif.html.

- Kuroboshi, M., Tanaka, H. & Kondo, T. (2015). Heterocycles, 90, 723–729.

- Lindner, E., Pabel, M. & Eichele, K. (1990). J. Organomet. Chem.386, 187–194.

- Lindner, E., Schauss, E., Hiller, W. & Fawzi, R. (1985). Chem. Ber.118, 3915–3931.

- Lindner, E., von Au, G. & Eberle, H.-J. (1981). Chem. Ber.114, 810–813.

- Martínez, A. G., Alvarez, R. M., Fraile, A. G., Subramanian, L. R. & Hanack, M. (1987). Synthesis, pp. 49–51.

- Martínez, A. G., Ríos, I. E. & Vilar, E. T. (1979). Synthesis, pp. 382–383.

- McKenna, R., Neidle, S., Kuroda, R. & Fox, B. W. (1989). Acta Cryst. C45, 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Neese, F. (2012). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci.2, 73–78.

- Neese, F. (2022). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci.12, e1606.

- Parsons, S., Flack, H. D. & Wagner, T. (2013). Acta Cryst. B69, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salomon, M. F. & Salomon, R. G. (1979). J. Am. Chem. Soc.101, 4290–4299.

- Shackelford, S. A., Chapman, R. D., Andreshak, J. L., Herrlinger, S. P., Hildreth, R. A. & Smith, J. C. (1985). J. Fluorine Chem.29, 123.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015a). Acta Cryst. A71, 3–8.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2015b). Acta Cryst. C71, 3–8.

- Spek, A. L. (2020). Acta Cryst. E76, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Varetto, U. (2002). MOLEKEL. Version 4.3. Swiss National Supercomputing Centre, Lugano, Switzerland.

- Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. (2005). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystal structure: contains datablock(s) global, 2, 1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj3019sup1.cif

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) 1. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup2.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup4.cdx

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup6.cml

Structure factors: contains datablock(s) 2. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup3.hkl

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup5.cdx

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30191sup6.cml

Supporting information file. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj30192sup7.cml

Packing of the title compounds. DOI: 10.1107/S2053229624005230/oj3019sup8.pdf