Abstract

In recent years, metabolomics, the systematic study of small-molecule metabolites in biological samples, has yielded fresh insights into the molecular determinants of pulmonary diseases and critical illness. The purpose of this article is to orient the reader to this emerging field by discussing the fundamental tenets underlying metabolomics research, the tools and techniques that serve as foundational methodologies, and the various statistical approaches to analysis of metabolomics datasets. We present several examples of metabolomics applied to pulmonary and critical care medicine to illustrate the potential of this avenue of research to deepen our understanding of pathophysiology. We conclude by reviewing recent advances in the field and future research directions that stand to further the goal of personalizing medicine to improve patient care.

Keywords: metabolomics, pulmonary vascular disease

The past two decades have witnessed significant advances in the field of systems biology (1, 2). Metabolomics, the latest addition to the omics sciences, is the systematic qualitative and quantitative study of endogenous and/or exogenous metabolites present in a biological sample (3, 4). Metabolites are the intermediates and end products of molecular regulatory mechanisms and therefore broadly reflect the physiologic state of the biological system sampled. This emerging methodology has been applied to various disciplines in science and medicine, including pulmonary and critical care medicine (5–9). The scope of metabolomics includes the identification and quantification of altered metabolism in association with specific traits and under specific conditions, for example, in health versus disease. Given its relative position downstream of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics in the transfer of biological sequence information, metabolomics is believed to provide a more dynamic readout of biology that is “closest” to phenotype.

Pulmonary and critical care medicine encompasses a wide range of complex and heterogeneous diseases. Application of metabolomics stands to enhance our understanding of the nuanced pathophysiology underlying these diseases, which could potentially bring about improved diagnostic and management strategies. The purpose of the present article is to review the basic principles and methodologies underlying metabolomics, with a specific focus on recent applications in pulmonary and critical care medicine. We conclude with a discussion of the latest technological advancements in metabolomics and current challenges and limitations faced by the field. This article was conceived in response to a call for omics papers from the Journal, and it aligns with the basic science core theme at the 2024 American Thoracic Society International Conference.

Fundamentals of Metabolomics

The fundamental premise underlying metabolomic profiling is that the metabolome, the sum total of small molecules (amino acids, lipids, sugars, xenobiotics, etc.) present in cells, tissues, and body fluids, reflects molecular processes first encoded by the genome, which are then transcribed, translated, and ultimately performed by downstream molecules possessing dynamic structures and functions that are subject to environmental and other contextual influences. The metabolome therefore offers a unique window into molecular determinants tightly linked with phenotypes.

Metabolomic profiling can be performed in a targeted or untargeted manner. Targeted metabolomics refers to the identification of a set list of metabolites designated a priori on the basis of their biological relevance to a given research question (10). Typically, metabolite identification is confirmed by comparison of the identified molecule with a defined back-end library. Often, this approach includes use of internal standards and calibration curves for accurate quantification.

Untargeted metabolomics attempts the comprehensive identification of all metabolites present in a biological sample, to the extent possible given a particular analytic platform (10). Different analytic methods may be used in a complementary fashion to broaden the metabolite coverage achieved (11). In contrast to RNA or proteins, different classes of detectable metabolites possess varying physicochemical properties, so the use of a single analytic method constrains metabolite coverage (12). With untargeted metabolomics, there may or may not be putative identification of the resolved metabolites.

Both targeted and untargeted metabolomics can be performed in a wide variety of biological sample types, ranging from serum or plasma to urine, BAL fluid, exhaled breath condensate, homogenized tissue preparations, cell lysates, and single cells (13). The particular research question under investigation motivates sample type selection. Considerations include whether the research question involves systemic metabolism or organ-specific metabolism, the accessibility of the biological system of interest, the ease and practicality of sample collection, and the specific metabolic information sought.

Analytic Tools and Techniques

Analytic platforms supporting metabolomics typically couple a separation method with a detection and quantification method. The separation method, such as liquid chromatography (LC) or gas chromatography (GC), is used to resolve complex mixtures of metabolites on the basis of their physical or chemical properties (14). After separation, a detection and quantification method, such as mass spectrometry (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, is used to identify and quantify metabolites (11). In general, LC is a more versatile method, in that it can resolve a broader range of compounds, including large, nonvolatile molecules, whereas GC is restricted to volatile, heat-stable compounds (15). Ultra-performance LC has become prevalent in recent years because of its higher resolution, speed, and efficiency compared with traditional high-performance LC. This technology allows faster, more efficient separation of metabolites, which is useful for high-throughput metabolomic studies.

There have been significant improvements in quantification methods, yielding increased sensitivity, accuracy, and precision of measurements (15). MS measures the mass-to-charge ratio of ions and is therefore limited mostly to the analysis of ionizable and volatile compounds. MS has high sensitivity for detecting and quantifying low-abundance analytes and requires small sample volumes, but the technique is destructive to samples. By contrast, NMR spectroscopy measures the interaction of atomic nuclei with an external magnetic field and is nondestructive (16, 17). NMR is less sensitive than MS and requires larger samples, but it provides more detailed structural information about molecules without fragmentation. Recent enhancements in NMR, such as increased magnetic field strength and the development of new pulse sequences, have improved its sensitivity and resolution (12, 18).

How to Launch a Metabolomics Study

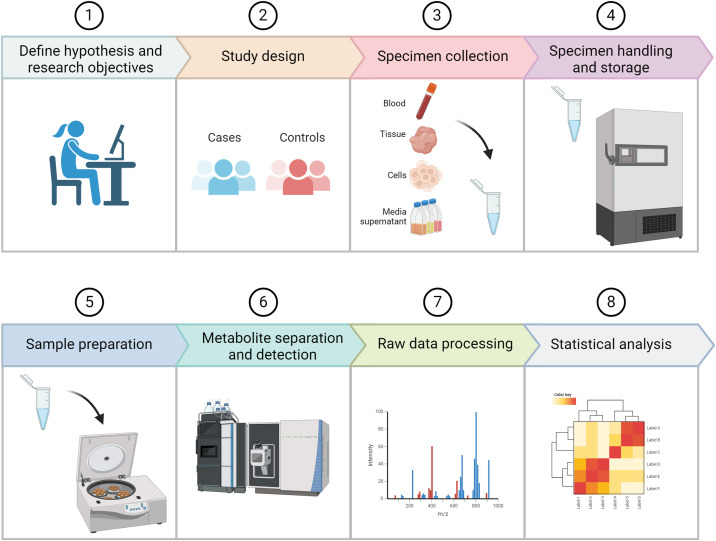

Once study hypotheses and research objectives are clearly defined, the optimal study design can be determined, and sample collection and handling must be carefully planned. Case-control and longitudinal studies are common prospective designs, and cross-sectional analyses are often performed on already available biospecimens. As with the design of any study, factors such as sample size and statistical power as well as potentially confounding variables should be carefully considered upfront. Once the optimal biospecimen type is determined, standardized protocols for prospective sample collection and handling must be established to minimize variability. For already banked specimens, the circumstances surrounding initial sample collection and storage should be as uniform as possible (e.g., fasting vs. fed state, time of day, methods used for processing, freeze and thaw cycles after storage). Once the biospecimens to be analyzed are identified, an appropriate analytic platform (e.g., NMR, LC–MS, GC–MS) can be selected on the basis of the research question. Specimen preparation requirements and specific protocols for metabolite extraction and detection will vary according to the platform chosen. Raw data from the instrument are then processed for normalization, peak alignment, and metabolite identification. Researchers who wish to analyze already available metabolite data, for hypothesis generation or for validation of their initial findings, can find publicly available datasets hosted by several searchable data repositories, including the Metabolomics Workbench (metabolomicsworkbench.org) and MetaboLights (ebi.ac.uk and metabolights). Figure 1 schematizes the fundamental steps needed to plan and execute a typical metabolomics study.

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstrating the fundamental steps needed to plan and execute a typical metabolomics study.

Approaches for Analyzing Metabolomics Data

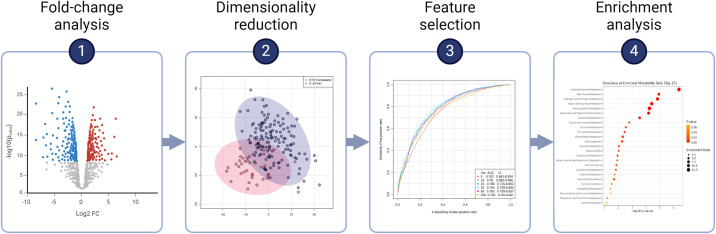

The statistical approach to a particular metabolomics analysis should be tailored to the complexity and dimensionality of the data to derive the most meaningful biological insights (19, 20). The choice of statistical method(s) depends largely on study design and objectives, and often multiple methods are used in tandem (Figure 2) (7, 21). Traditional statistical approaches such as t tests and ANOVA are often used to compare the fold changes of metabolite concentrations between groups, thereby identifying significant between-group differences. Linear and logistic regression models can be used to examine associations between metabolite concentrations and clinical variables. When traditional hypothesis-based statistics with significance testing are used, techniques such as Bonferroni correction or false discovery rate correction are essential to account for the multiplicity inherent to high-dimensional data (22).

Figure 2.

Example analytic pipeline for a metabolomics dataset incorporating univariate analysis, multivariate analysis, and metabolite set enrichment analysis in tandem. Panels 2 through 4 are reproduced by permission from Reference 45. AUC = area under the curve; CI = confidence interval; CTD = connective tissue disease; FC = fold change; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; Var. = variables.

Various dimensionality reduction techniques are well suited to metabolomics data (7). Principal-component analysis (PCA) is an unsupervised multivariate method that reduces dataset complexity without losing key information. PCA projects high-dimensional data into lower dimensional space by defining orthogonal axes (principal components) along which variance in the data is maximized (23, 24). PCA thereby reduces the complexity of the data, reducing a large number of features (here, metabolites) into a smaller feature set that still explains most of the overall metabolic variability present. In this way, PCA reveals underlying data structures and can uncover patterns and relationships within the data. Partial least squares with discriminant analysis and related methods (e.g., orthogonal partial least squares) are supervised multivariate methods (25, 26). With these supervised methods, class labels are known (e.g., subjects are identified as members of healthy vs. diseased groups), and the analysis distinguishes metabolic differences between labeled groups while also identifying and prioritizing the metabolites most important for discrimination (27).

Several popular machine learning methods involving penalized regression are particularly well suited to metabolomics data, including least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), elastic net regression, and sparse partial least squares regression (28). These techniques are generally more robust against multicollinearity and overfitting, making them ideal for omics datasets containing highly correlated features. LASSO penalizes the absolute size of coefficients during model fitting and reduces some coefficients to zero, effectively selecting the most significant variables into a final predictive model. Elastic net regression combines LASSO and ridge regression techniques, regularizing models and striking a balance between variable selection and model complexity. Sparse partial least squares performs dimensionality reduction simultaneously with variable selection, also resulting in models that include only the most relevant predictors (26). In general, machine learning methods, particularly those based on sparsity, optimize model predictive performance and interpretability when datasets have more features (metabolites) than samples, which is common in metabolomics studies (29, 30).

Several bioinformatic methods have been developed to infer biological meaning from metabolomics results. Examples include novel methods of correlation analysis that aim to understand the interactions and networks formed among individual metabolite features. For example, debiased sparse partial correlation estimates the partial correlation matrix in high-dimensional datasets by introducing sparsity, allowing a more accurate representation of the true underlying relationships between metabolites (31). This approach enhances the reliability of inferred network structures as compared with traditional correlation analysis, which might yield biased results in the context of high dimensionality. Pathway analysis generally refers to the integration of statistical findings with curated pathway databases (e.g., Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes [KEGG] and Genomes, Small Molecule Pathway Database [SMPD]) to understand the biological relevance of metabolic aberrations (32, 33).

Integration of Metabolomics with Other Omics Techniques

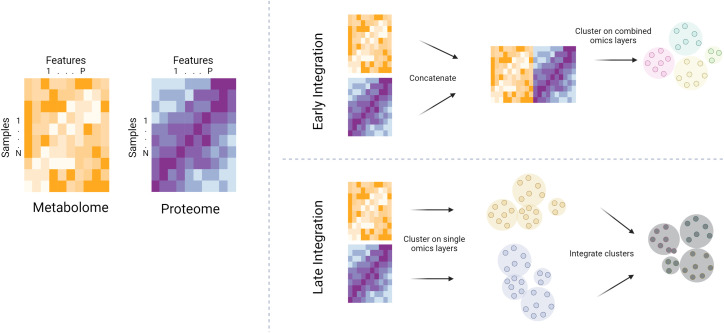

There is a growing emphasis on integrating metabolomics with other omics technologies (genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics) to gain a more holistic understanding of biological systems (34). In general, multiomics integration across individual omics layers can be performed “early” or “late” in an analytic pipeline (Figure 3) (35). Early integration involves concatenating omics datasets at the beginning of an analysis, allowing integrated modeling. This approach can reveal interactions between omics layers but is often complicated by heterogeneity of data types and scales. Late integration, on the other hand, involves analyzing each omics dataset separately and then integrating the resulting features at a later stage of the analysis. This method maintains the distinct characteristics of each omics dataset, potentially simplifying interpretation, but might overlook complex interomics interactions.

Figure 3.

Schematized depiction of early versus late integration of individual omics layers. The yellow heatmap represents a hypothetical metabolome, while the purple heatmap represents a hypothetical proteome for a given sample set. With early integration, the metabolomic and proteomic datasets are concatenated, then clustering (for example) is performed on the combined feature set. With late integration, the omics layers are clustered separately, then clusterings are integrated at a later stage of the analysis.

Applications in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine

Metabolomics is typically used in biomedical research in the service of one of several key objectives: understanding disease mechanisms, dissecting heterogeneity (so-called endophenotyping), identifying novel therapeutic targets, or identifying biomarkers. In observational epidemiologic studies, biomarker identification is generally in the service of achieving earlier or more accurate diagnosis, monitoring disease progression and/or response to therapy, or predicting clinically relevant events such as exacerbation, clinical worsening, or death.

Examples in Asthma

Recent work by Kelly and colleagues offers an example of applying metabolomics toward resolving clinical heterogeneity in asthma (36). The authors applied an unsupervised clustering method to blood metabolomic profiles and derived five groups of patients with distinct metabolic endotypes and significant differences in asthma-relevant spirometric variables. Crucially, these five clusters were validated in a second asthma cohort. When metabolic differences driving cluster assignment were interrogated, various lipids, including cholesterol esters, triglycerides, and fatty acids, proved to be the most important features driving cluster assignment. This parsing of heterogeneity paves a path for a precision medicine approach to asthma treatment, whereby different groups of patients may be understood to have distinct alterations in pathobiology, with treatments potentially tailored to the specific molecular aberrations observed in a given group.

Kelly and colleagues also examined the pharmacometabolomics of bronchodilator response in asthma (37). Bronchodilator response is a surrogate for asthma control that declines with age; thus the authors examined age-by-metabolite interactions to explore the metabolome as a potential modifier of the effect of age on bronchodilator response. They found that the relationship between advancing age and reduced bronchodilator response was attenuated in subjects with higher concentrations of cholesterol esters and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). These findings suggest that these molecules could play important roles in potentiating bronchodilator response, and future studies should investigate these molecules’ potential as therapeutic targets.

Kachroo and colleagues investigated metabolomic profiles from 14,000 subjects across four distinct asthma cohorts and identified an association between metabolite markers of adrenal suppression and prevalent asthma (38). The investigators demonstrated that this metabolic signature of adrenal suppression was most robust in patients prescribed inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs). Furthermore, they used linked electronic medical record data to show an inverse association between circulating cortisol concentrations and ICS use. Taken together, Kachroo and colleagues’ findings suggest a causal relationship between ICS use and adrenal insufficiency in patients with asthma, an example of a potentially detrimental response to ICS therapy that deserves greater awareness.

Examples in Pulmonary Hypertension

Several metabolomics studies in pulmonary hypertension (PH) have yielded results that challenge traditional clinically based classification and treatment schemes. Alotaibi and colleagues (39) examined metabolomic differences between systemic sclerosis–associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and idiopathic PAH (IPAH), which are commonly understood to represent two pathophysiologically distinct subtypes of group 1 PAH (40–42). Multiple epidemiologic studies have demonstrated worse survival for patients with systemic sclerosis–associated PAH (40, 43, 44). The authors identified broad between-group metabolic differences, including differences in sex hormones, fatty acids, and eicosanoids (39).

The PVDOMICS (Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics) study group investigated a similar question, analyzing metabolomic differences between connective tissue disease–associated PAH and IPAH (45). With a “top-down” approach, in which metabolic differences between the two clinically phenotyped groups were examined, significant between-group differences in sex hormone metabolism and fatty acid metabolism were observed, in alignment with Alotaibi and colleagues’ work (39). However, with a “bottom-up” approach, in which unsupervised clustering on metabolite data was performed with all patients with PAH, regardless of subtype, three unique clusters formed, each with a mix of patients with connective tissue disease–associated PAH and those with IPAH included. These three clusters demonstrated significant differences in hemodynamics, right ventricular function, and transplantation-free survival. Abnormalities in ketone body metabolism and fatty acid metabolism were most important in driving cluster assignment in the top-up approach.

Heresi and colleagues (46) investigated differences between healthy control subjects and patients with either chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH) or PAH, which are distinct diagnoses classified into two separate PH groups (group 4 and group 1, respectively) in the current World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension classification system (47). Despite clear differences in clinical presentations and treatment strategies between CTEPH and PAH, Heresi and colleagues showed that metabolic differences between patients with CTEPH and healthy control subjects were similar to those between patients with PAH and healthy control subjects, with common aberrations in fatty acids, phospholipids, and the ketone β-hydroxybutyrate (46). Similar lipid aberrations in CTEPH were observed by Swietlik and colleagues, who also demonstrated that partial metabolic correction occurred after patients with CTEPH underwent pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (48).

Taken together, these metabolomics studies in PH collectively suggest that aberrant lipid metabolism, particularly aberrant fatty acid metabolism, might be a common pathogenic feature across intrinsic pulmonary vasculopathies, regardless of clinical labels.

Examples in Pulmonary Fibrosis

Elements of aberrant lipid metabolism are also observed in pulmonary fibrosis. In a small, early study of metabolic differences in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) versus healthy control subjects, lysophosphatidylcholine, a precursor of lysophosphatidic acid, was one of 10 serum metabolites that discriminated IPF (49). More recently, a larger analysis of subjects enrolled in the IPF-PRO (Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Prospective Outcomes) registry corroborated aberrant lipid metabolism in IPF, demonstrating increased concentrations of circulating nonesterified fatty acids, long-chain acylcarnitines, and ceramides in patients with IPF (50). Moreover, higher concentrations of several differentially abundant metabolites, including acylcarnitines and sphingomyelins, were associated with more severe disease and poorer clinical outcomes (50). Other investigators have shown that treatment of patients with IPF with the antifibrotic drug nintedanib induces alterations in the circulating lipidome, with some (but not all) of the induced alterations congruent with correction of disease-associated lipidomic dysregulation (51). This result suggests that some lipidomic features may be worthy of investigation as markers of response to antifibrotic therapies in IPF.

Odoom and colleagues examined the metabolomic profile of exhaled breath condensate collected from patients with pulmonary fibrosis of a different etiology, radiation-induced lung injury (52). Patients who received therapeutic thoracic irradiation for lung cancer were compared with patients with lung cancer who had not received radiation treatments, smokers (at risk for lung cancer), and healthy control subjects. The authors found that alterations in tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism were specific to radiation-induced lung injury and posited that radiation upregulates glycolysis and increases conversion of pyruvate to lactate, which then promotes fibrosis, thereby generating a clear hypothesis to guide follow-up mechanistic studies.

Examples in Critical Care

One particular line of inquiry in critical care illustrates how metabolomics studies could point to candidate metabolically targeted therapies. In a post hoc analysis of clinical trial data, Jennaro and colleagues found that circulating acylcarnitine concentrations were associated with extubation and freedom from organ support in patients with septic shock (53). In a second study, Jennaro and colleagues examined longitudinal metabolite profiles in patients with septic shock and moderate organ dysfunction and identified metabolite patterns that discriminated survivors and nonsurvivors at 28 days (54). Among other differences, acylcarnitines were higher at baseline in nonsurvivors, and this elevation persisted throughout the time course.

Acylcarnitines are metabolites formed in the process of transporting fatty acids into mitochondria, and L-carnitine plays a crucial role in fatty acid transport across the mitochondrial membrane (55). A phase II clinical trial, the RACE (Rapid Administration of Carnitine in Sepsis) trial, investigated L-carnitine as a potential therapy for patients with septic shock and revealed a trend toward improved survival, but the results were not statistically significant (56). However, in an ancillary metabolomics analysis of RACE trial data, investigators found that a subset of subjects with high acylcarnitine concentrations before the initiation of therapy had significantly reduced 90-day mortality (57). This result suggests that correction of metabolic dysfunction might be most beneficial in a subset of patients with the most severe metabolic derangements, and prospective investigation of the benefit of L-carnitine administration in select patients with septic shock and high circulating acylcarnitine concentrations may be warranted. In general, there may be a role for metabolomics in selectively enriching trials for participants most likely to benefit from metabolically targeted interventions.

Animal Models of Pulmonary Diseases

Metabolomics studies performed in experimental models illustrate the potential for metabolomics to elucidate molecular determinants of human diseases using cells and tissues that are difficult to obtain from living human subjects. Asthma researchers focused on menopause-associated asthma created a novel mouse model combining menopause induction and allergen exposure (58). Metabolic profiling of these animals’ serum and BAL fluid using LC–MS demonstrated altered concentrations of glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid, phosphocreatine, and pyroglutamic acid. Several implicated metabolites showed strong correlations with total airway resistance, suggesting potential drivers and biomarkers of menopause-associated asthma (59).

PH researchers have resolved the tissue-specific evolution of metabolic dysregulation that occurs as experimental PH develops in the Sugen and chronic hypoxia rodent model of PH, which is believed to most faithfully recapitulate human disease (60). Metabolomics analyses of lung microvascular endothelial cells isolated from the Sugen model have demonstrated that the glycolytic shift known to occur in human PAH is observed in the microvasculature and that intracellular glutamine concentrations are used to produce glutathione, thus illuminating a mechanism possibly regulating endothelial redox balance (61).

Recent Advances and Breakthroughs in Metabolomics

Technological Advances

The emergence of ever more sophisticated microfluidic devices is enabling the development of single-cell metabolomics, which promises to provide a detailed view of metabolic activity at single-cell resolution, thus uncovering cell-to-cell metabolic variability that bulk analysis of a tissue or body fluid cannot reveal (62). Spatial metabolomics, also known as metabolic imaging, is an emerging field that combines metabolomics with techniques to map and visualize the distribution of metabolites within biological tissues (63, 64). This approach provides a comprehensive view of the metabolic status of a sample while retaining spatial context, but spatial resolution down to the single-cell level remains a challenge.

Spatial metabolomics relies on breakthrough imaging techniques, including matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization, desorption electrospray ionization, and secondary ion MS (62, 64).

Efforts are under way to improve our ability to analyze metabolites in living cells, which will enable a deeper understanding of dynamic metabolic processes. Techniques such as live-cell microscopy combined with fluorescent biosensors have been used to monitor real-time metabolic changes at the single-cell level. The Seahorse Analyzer, developed by Agilent Technologies, is used for real-time measurement of cellular metabolism (65–67). The device measures oxygen consumption rate, which is indicative of mitochondrial respiration, and extracellular acidification rate, which reflects lactic acid production from glycolysis, to assess real-time cellular energy production.

Advances in stable isotope labeling techniques have improved the quantification and tracking of metabolic fluxes through cells and tissues, providing deeper insights into metabolic pathways and their regulation. Stable isotope tracing has been coupled with matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization to reveal the spatial resolution of metabolic flux in mammalian tissues (68). In a recent use case, investigators leveraged 13C-labeled substrates and MS to show differences in the use of glucose, glutamine, and fatty acids between pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells and between PH and control cells (69). The authors found that TGF-β (transforming growth factor-β) treatment of cells recapitulated some of the aberrant metabolic flux. Later, in unrelated work, a novel fusion protein called sotatercept, which specifically affects TGF-β signaling, showed efficacy in improving pulmonary hemodynamics and exercise capacity in patients with PAH already prescribed standard-of-care PH-specific therapies (70, 71).

Methodologic Advances in Data Analysis

Several efforts in biostatistics and bioinformatics are aimed at maximizing the biological insights gained from metabolomics datasets. Techniques initially developed for differential gene expression analysis are being successfully adapted to metabolomics analysis, including weighted gene correlation network analysis and metabolite set enrichment analysis, a methodologic analog of gene set enrichment analysis (72, 73). Statistical packages such as COMPASS (https://github.com/YosefLab/Compass) and scFLUX (https://github.com/changwn/scFEA) can be leveraged to predict metabolism from single-cell gene expression data (74, 75). Given the potential for post-translational modification and other downstream regulatory mechanisms, however, such predictions require direct assessment and confirmation with metabolite assays.

A frequent goal of epidemiologic research is causal inference, and therefore efforts are under way to incorporate causal inference into omics analyses (76). In genomics, for example, Mendelian randomization can be leveraged to estimate the causal effect of an exposure on an outcome of interest using randomly assorted genetic variants as instrumental variables (77). Efforts are under way to similarly develop methods for causal inference in metabolomics. Targeted MLE is an advanced statistical technique useful in high-dimensional data settings that could be used for making causal inferences about relationships between metabolites and biological or clinical outcomes (78). Targeted MLE combines ideas from machine learning with traditional statistical approaches to provide more accurate estimates.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite the many technological and methodologic advances driving the field forward, there remain several challenges to address and limitations to overcome. One major challenge in metabolomics research will be standardizing protocols across the discipline. Methods for sample collection, processing, and analysis vary widely, making comparison of results across studies challenging. The Consortium of Metabolomics Studies Network is a National Cancer Institute–sponsored initiative aimed at improving standardization and harmonization across collaborators researching the human metabolome (79, 80).

Improving accuracy in identifying and quantitating metabolites remains a priority, and as technical methods improve, the field will need to adopt standards for controlling sources of variability in sample collection (e.g., time of day, diet), encourage consistent use of internal standards for metabolite identification, and routinely incorporate methods for mitigating batch effects across runs.

We are increasingly generating large and complex datasets and need to remain mindful of the “curse of dimensionality,” whereby the large number of features relative to the number of samples can lead to model overfitting and spurious associations. Effective feature transformation and scaling and appropriate handling of missing data, together with correction for multiple testing and adjustment for clinical variables that may act as confounders, are critically important steps to build in to analytic pipelines.

The complexity of models constructed and the lack of absolute quantification of included metabolites further complicate the interpretation and clinical application of metabolomics data. The semiquantitative nature of (most) metabolomics data precludes the rigorous testing of specific cut points in external validation datasets. Moreover, whether multimetabolite models can reliably outperform simpler clinical models in predicting outcomes prospectively remains to be seen.

Finally, there is an inherent challenge in balancing the accessibility of biological sample matrices with the goal of understanding organ-specific or tissue-specific pathobiology. The circulating plasma metabolome is commonly sampled, but this matrix represents collective metabolic activity across all organ systems and may not accurately reflect metabolic activity specific to a disease of interest. In contrast, metabolomics analyses of particular cells and tissues that manifest disease can be confounded by the techniques required to acquire these specimens, which can themselves trigger significant metabolic shifts. Moving forward, the field would benefit from the development of novel methods for studying compartment-specific metabolism in living subjects.

Future Directions and Conclusions

The future of metabolomics in pulmonary and critical care medicine lies in moving beyond unbiased discovery toward hypothesis-driven studies that either follow up on omics results with mechanistic experiments or build omics methods into well-defined, hypothesis-based research questions. There is a pressing need for molecular and functional validation of proposed pathways and mechanisms uncovered by increasingly sophisticated and well-designed omics analyses. Because of this need, the field is ripe for collaborative and interdisciplinary research that brings together clinicians, epidemiologists, bench researchers, and statisticians working in teams to address complex research questions (81).

Metabolomics studies have already begun to provide novel insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities in pulmonary and critical care medicine. The challenges and limitations of the field, although substantial, provide a roadmap for future research and development. As the field progresses, the continued evolution of metabolomics technologies, coupled with a more standardized approach to research and an emphasis on collaborative, interdisciplinary study, will undoubtedly advance our understanding and application of metabolomics in health care. The promise of metabolomics for enhancing personalized medicine and tailoring clinical decision making remains an exciting prospect, heralding a new era in the management and treatment of pulmonary diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL142769, K23HL153781, and R35HL135830 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI178782 and R01AI170913.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2024-0080PS on March 28, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Nicholson JK, Lindon JC. Systems biology: metabonomics. Nature . 2008;455:1054–1056. doi: 10.1038/4551054a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gomes B, Ashley EA. Artificial intelligence in molecular medicine. N Engl J Med . 2023;388:2456–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2204787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol . 2016;17:451–459. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schrimpe-Rutledge AC, Codreanu SG, Sherrod SD, McLean JA. Untargeted metabolomics strategies-challenges and emerging directions. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom . 2016;27:1897–1905. doi: 10.1007/s13361-016-1469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis GD. The emerging role of metabolomics in the development of biomarkers for pulmonary hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases (2013 Grover Conference series) Pulm Circ . 2014;4:417–423. doi: 10.1086/677369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rattray NJ, Hamrang Z, Trivedi DK, Goodacre R, Fowler SJ. Taking your breath away: metabolomics breathes life in to personalized medicine. Trends Biotechnol . 2014;32:538–548. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reinke SN, Chaleckis R, Wheelock CE. Metabolomics in pulmonary medicine: extracting the most from your data. Eur Respir J . 2022;60:2200102. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00102-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stringer KA, McKay RT, Karnovsky A, Quémerais B, Lacy P. Metabolomics and its application to acute lung diseases. Front Immunol . 2016;7:44. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harbaum L, Rhodes CJ, Otero-Núñez P, Wharton J, Wilkins MR. The application of ‘omics’ to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Br J Pharmacol . 2021;178:108–120. doi: 10.1111/bph.15056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng S, Shah SH, Corwin EJ, Fiehn O, Fitzgerald RL, Gerszten RE, et al. American Heart Association Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council Potential impact and study considerations of metabolomics in cardiovascular health and disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Genet . 2017;10:e000032. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moco S, Buescher JM. Metabolomics: going deeper, going broader, going further. Methods Mol Biol . 2023;2554:155–178. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2624-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu W, Su X, Klein MS, Lewis IA, Fiehn O, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolite measurement: pitfalls to avoid and practices to follow. Annu Rev Biochem . 2017;86:277–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowler RP, Wendt CH, Fessler MB, Foster MW, Kelly RS, Lasky-Su J, et al. American Thoracic Society Workgroup on Metabolomics and Proteomics New strategies and challenges in lung proteomics and metabolomics: an official American Thoracic Society workshop report. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2017;14:1721–1743. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201710-770WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jespers S, Broeckhoven K, Desmet G. Comparing the separation speed of contemporary LC SFC, and GC. LC GC Eur . 2017;30:284–291. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perez de Souza L, Alseekh S, Scossa F, Fernie AR. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry variants for metabolomics research. Nat Methods . 2021;18:733–746. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reif B, Ashbrook SE, Emsley L, Hong M. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Nat Rev Methods Primers . 2021;1:2. doi: 10.1038/s43586-020-00002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Radda GK. The use of NMR spectroscopy for the understanding of disease. Science . 1986;233:640–645. doi: 10.1126/science.3726553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Blahut J, Brandl MJ, Pradhan T, Reif B, Tošner Z. Sensitivity-enhanced multidimensional solid-state NMR spectroscopy by optimal-control-based transverse mixing sequences. J Am Chem Soc . 2022;144:17336–17340. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c06568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bijlsma S, Bobeldijk I, Verheij ER, Ramaker R, Kochhar S, Macdonald IA, et al. Large-scale human metabolomics studies: a strategy for data (pre-) processing and validation. Anal Chem . 2006;78:567–574. doi: 10.1021/ac051495j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chong J, Yamamoto M, Xia J. MetaboAnalystR 2.0: from raw spectra to biological insights. Metabolites . 2019;9:57. doi: 10.3390/metabo9030057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tzoulaki I, Ebbels TM, Valdes A, Elliott P, Ioannidis JP. Design and analysis of metabolomics studies in epidemiologic research: a primer on -omic technologies. Am J Epidemiol . 2014;180:129–139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Broadhurst DI, Kell DB. Statistical strategies for avoiding false discoveries in metabolomics and related experiments. Metabolomics . 2006;2:171–196. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet . 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet . 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bylesjö M, Rantalainen M, Cloarec O, Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Trygg J. OPLS discriminant analysis: combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. J Chemometr . 2006;20:341–351. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chun H, Keleş S. Sparse partial least squares regression for simultaneous dimension reduction and variable selection. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol . 2010;72:3–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2009.00723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Galindo-Prieto B, Eriksson L, Trygg J. Variable influence on projection (VIP) for orthogonal projections to latent structures (OPLS) J Chemometr . 2014;28:623–632. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu J, Liang G, Siegmund KD, Lewinger JP. Data integration by multi-tuning parameter elastic net regression. BMC Bioinformatics . 2018;19:369. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2401-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henglin M, Claggett BL, Antonelli J, Alotaibi M, Magalang GA, Watrous JD, et al. Quantitative comparison of statistical methods for analyzing human metabolomics data. Metabolites . 2022;12:519. doi: 10.3390/metabo12060519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alotaibi M, Liu Y, Magalang GA, Kwan AC, Ebinger JE, Nichols WC, et al. Deriving convergent and divergent metabolomic correlates of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Metabolites . 2023;13:802. doi: 10.3390/metabo13070802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Basu S, Duren W, Evans CR, Burant CF, Michailidis G, Karnovsky A. Sparse network modeling and Metscape-based visualization methods for the analysis of large-scale metabolomics data. Bioinformatics . 2017;33:1545–1553. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res . 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nat Protoc . 2011;6:743–760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reel PS, Reel S, Pearson E, Trucco E, Jefferson E. Using machine learning approaches for multi-omics data analysis: a review. Biotechnol Adv . 2021;49:107739. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harbig TA, Fratte J, Krone M, Nieselt K. OmicsTIDE: interactive exploration of trends in multi-omics data. Bioinform Adv . 2023;3:vbac093. doi: 10.1093/bioadv/vbac093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kelly RS, Mendez KM, Huang M, Hobbs BD, Clish CB, Gerszten R, et al. Metabo-endotypes of asthma reveal differences in lung function: discovery and validation in two TOPMed cohorts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;205:288–299. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202105-1268OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kelly RS, Sordillo JE, Lutz SM, Avila L, Soto-Quiros M, Celedón JC, et al. Pharmacometabolomics of bronchodilator response in asthma and the role of age-metabolite interactions. Metabolites . 2019;9:179. doi: 10.3390/metabo9090179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kachroo P, Stewart ID, Kelly RS, Stav M, Mendez K, Dahlin A, et al. Metabolomic profiling reveals extensive adrenal suppression due to inhaled corticosteroid therapy in asthma. Nat Med . 2022;28:814–822. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01714-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alotaibi M, Shao J, Pauciulo MW, Nichols WC, Hemnes AR, Malhotra A, et al. Metabolomic profiles differentiate scleroderma-PAH from idiopathic PAH and correspond with worsened functional capacity. Chest . 2023;163:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.08.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ramjug S, Hussain N, Hurdman J, Billings C, Charalampopoulos A, Elliot CA, et al. Idiopathic and systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a comparison of demographic, hemodynamic, and MRI characteristics and outcomes. Chest . 2017;152:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kelemen BW, Mathai SC, Tedford RJ, Damico RL, Corona-Villalobos C, Kolb TM, et al. Right ventricular remodeling in idiopathic and scleroderma-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: two distinct phenotypes. Pulm Circ . 2015;5:327–334. doi: 10.1086/680356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsu S, Kokkonen-Simon KM, Kirk JA, Kolb TM, Damico RL, Mathai SC, et al. Right ventricular myofilament functional differences in humans with systemic sclerosis-associated versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation . 2018;137:2360–2370. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chung L, Farber HW, Benza R, Miller DP, Parsons L, Hassoun PM, et al. Unique predictors of mortality in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in the REVEAL registry. Chest . 2014;146:1494–1504. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fisher MR, Mathai SC, Champion HC, Girgis RE, Housten-Harris T, Hummers L, et al. Clinical differences between idiopathic and scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum . 2006;54:3043–3050. doi: 10.1002/art.22069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simpson CE, Hemnes AR, Griffiths M, Grunig G, Tang WHW, Garcia JGN, et al. PVDOMICS Study Group Metabolomic differences in connective tissue disease-associated versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension in the PVDOMICS cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol . 2023;75:2240–2251. doi: 10.1002/art.42632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heresi GA, Mey JT, Bartholomew JR, Haddadin IS, Tonelli AR, Dweik RA, et al. Plasma metabolomic profile in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ . 2020;10:2045894019890553. doi: 10.1177/2045894019890553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J . 2019;53:1801913. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Swietlik EM, Ghataorhe P, Zalewska KI, Wharton J, Howard LS, Taboada D, et al. Plasma metabolomics exhibit response to therapy in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J . 2021;57:2003201. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03201-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rindlisbacher B, Schmid C, Geiser T, Bovet C, Funke-Chambour M. Serum metabolic profiling identified a distinct metabolic signature in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—a potential biomarker role for LysoPC. Respir Res . 2018;19:7. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Summer R, Todd JL, Neely ML, Lobo LJ, Namen A, Newby LK, et al. Circulating metabolic profile in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: data from the IPF-PRO Registry. Respir Res . 2024;25:58. doi: 10.1186/s12931-023-02644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Seeliger B, Carleo A, Wendel-Garcia PD, Fuge J, Montes-Warboys A, Schuchardt S, et al. Changes in serum metabolomics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and effect of approved antifibrotic medication. Front Pharmacol . 2022;13:837680. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.837680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Odoom JP-L, Freeberg MAT, Camus SV, Toft R, Szomju BB, Sanchez Rosado RM, et al. Exhaled breath condensate identifies metabolic dysregulation in patients with radiation-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2023;324:L863–L869. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00439.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jennaro TS, Viglianti EM, Ingraham NE, Jones AE, Stringer KA, Puskarich MA. Serum levels of acylcarnitines and amino acids are associated with liberation from organ support in patients with septic shock. J Clin Med . 2022;11:627. doi: 10.3390/jcm11030627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jennaro TS, Puskarich MA, Evans CR, Karnovsky A, Flott TL, McLellan LA, et al. Sustained perturbation of metabolism and metabolic subphenotypes are associated with mortality and protein markers of the host response. Crit Care Explor . 2023;5:e0881. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Longo N, Amat di San Filippo C, Pasquali M. Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet . 2006;142C:77–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jones AE, Puskarich MA, Shapiro NI, Guirgis FW, Runyon M, Adams JY, et al. Effect of levocarnitine vs placebo as an adjunctive treatment for septic shock: the Rapid Administration of Carnitine in Sepsis (RACE) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open . 2018;1:e186076. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Puskarich MA, Jennaro TS, Gillies CE, Evans CR, Karnovsky A, McHugh CE, et al. RACE Investigators Pharmacometabolomics identifies candidate predictor metabolites of an L-carnitine treatment mortality benefit in septic shock. Clin Transl Sci . 2021;14:2288–2299. doi: 10.1111/cts.13088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pederson WP, Ellerman LM, Sandoval EC, Boitano S, Frye JB, Doyle KP, et al. Development of a novel mouse model of menopause-associated asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2022;67:605–609. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2022-0181LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pederson WP, Ellerman LM, Jin Y, Gu H, Ledford JG. Metabolomic profiling in mouse model of menopause-associated asthma. Metabolites . 2023;13:546. doi: 10.3390/metabo13040546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Simpson CE, Ambade AS, Harlan R, Roux A, Graham D, Klauer N, et al. Spatial and temporal resolution of metabolic dysregulation in the Sugen hypoxia model of pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ . 2023;13:e12260. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Philip N, Pi H, Gadkari M, Yun X, Huetsch J, Zhang C, et al. Transpulmonary amino acid metabolism in the sugen hypoxia model of pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ . 2023;13:e12205. doi: 10.1002/pul2.12205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hu T, Allam M, Cai S, Henderson W, Yueh B, Garipcan A, et al. Single-cell spatial metabolomics with cell-type specific protein profiling for tissue systems biology. Nat Commun . 2023;14:8260. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-43917-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Alexandrov T. Spatial metabolomics: from a niche field towards a driver of innovation. Nat Metab . 2023;5:1443–1445. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Conroy LR, Clarke HA, Allison DB, Valenca SS, Sun Q, Hawkinson TR, et al. Spatial metabolomics reveals glycogen as an actionable target for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat Commun . 2023;14:2759. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38437-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bhatia S, Thompson EW, Gunter JH. Studying the metabolism of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity using the Seahorse XFe96 extracellular flux analyzer. Methods Mol Biol . 2021;2179:327–340. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0779-4_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Caines JK, Barnes DA, Berry MD. The use of Seahorse XF assays to interrogate real-time energy metabolism in cancer cell lines. Methods Mol Biol . 2022;2508:225–234. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2376-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Traba J, Antón OM. Assessing changes in human natural killer cell metabolism using the Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Methods Mol Biol . 2022;2463:165–180. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-2160-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang L, Xing X, Zeng X, Jackson SR, TeSlaa T, Al-Dalahmah O, et al. Spatially resolved isotope tracing reveals tissue metabolic activity. Nat Methods . 2022;19:223–230. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01378-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hernandez-Saavedra D, Sanders L, Freeman S, Reisz JA, Lee MH, Mickael C, et al. Stable isotope metabolomics of pulmonary artery smooth muscle and endothelial cells in pulmonary hypertension and with TGF-beta treatment. Sci Rep . 2020;10:413. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, McLaughlin VV, et al. STELLAR Trial Investigators Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med . 2023;388:1478–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2213558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Humbert M, McLaughlin V, Gibbs JSR, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hoeper MM, Preston IR, et al. PULSAR Trial Investigators Sotatercept for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med . 2021;384:1204–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fitzgerald KC, Smith MD, Kim S, Sotirchos ES, Kornberg MD, Douglas M, et al. Multi-omic evaluation of metabolic alterations in multiple sclerosis identifies shifts in aromatic amino acid metabolism. Cell Rep Med . 2021;2:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Drier Y, Sheffer M, Domany E. Pathway-based personalized analysis of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2013;110:6388–6393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219651110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wagner A, Wang C, Fessler J, DeTomaso D, Avila-Pacheco J, Kaminski J, et al. Metabolic modeling of single Th17 cells reveals regulators of autoimmunity. Cell . 2021;184:4168–4185.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhang Z, Zhu H, Dang P, Wang J, Chang W, Wang X, et al. FLUXestimator: a webserver for predicting metabolic flux and variations using transcriptomics data. Nucleic Acids Res . 2023;51:W180–W190. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hernán MA. Methods of public health research—strengthening causal inference from observational data. N Engl J Med . 2021;385:1345–1348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2113319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Harbaum L, Rhodes CJ, Wharton J, Lawrie A, Karnes JH, Desai AA, et al. U.K. National Institute for Health Research BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium, U.K. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Cohort Study Consortium, and U.S. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank Consortium Mining the plasma proteome for insights into the molecular pathology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;205:1449–1460. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2106OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Smith MJ, Phillips RV, Luque-Fernandez MA, Maringe C. Application of targeted maximum likelihood estimation in public health and epidemiological studies: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol . 2023;86:34–48.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Playdon MC, Joshi AD, Tabung FK, Cheng S, Henglin M, Kim A, et al. Metabolomics analytics workflow for epidemiological research: perspectives from the Consortium of Metabolomics Studies (COMETS) Metabolites . 2019;9:145. doi: 10.3390/metabo9070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yu B, Zanetti KA, Temprosa M, Albanes D, Appel N, Barrera CB, et al. The Consortium of Metabolomics Studies (COMETS): metabolomics in 47 prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol . 2019;188:991–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. van Roekel EH, Loftfield E, Kelly RS, Zeleznik OA, Zanetti KA. Metabolomics in epidemiologic research: challenges and opportunities for early-career epidemiologists. Metabolomics . 2019;15:9. doi: 10.1007/s11306-018-1468-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]