Abstract

Objective

To improve sustainability of a patient decision aid for systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer, we evaluated real-world experiences and identified ways to optimize decision aid content and future implementation.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews with patients and medical oncologists addressed two main subjects: user experience and decision aid content. Content analysis was applied. Fifteen experts discussed the results and devised improvements based on experience and literature review.

Results

Thirteen users were interviewed. They confirmed the relevance of the decision aid for shared decision making. Areas for improvement of content concerned; 1) outdated and missing information, 2) an imbalance in presentation of treatment benefits and harms, and 3) medical oncologists' expressed preference for a more center-specific or patient individualized decision aid, presenting a selection of the guideline recommended treatment options. Key points for improvement of implementation were better alignment within the care pathway, and clear instruction to users.

Conclusion

We identified relevant opportunities for improvement of an existing decision aid and developed an updated version and accompanying implementation strategy accordingly.

Innovation

This paper outlines an approach for continued decision aid and implementation strategy development which will add to sustainability. Implementation success of the improved decision aid is currently being studied in a multi-center mixed-methods implementation study.

Keywords: Shared decision making, Decision aid, Metastatic colorectal cancer, Qualitative research, Continued development, Sustainability, Implementation, Quality improvement

Highlights

-

•

Patient decision aids (PtDAs) support shared decision making (SDM) in oncology.

-

•

Evaluation and continued development of PtDAs is essential to reach sustainability.

-

•

Real-world users found the PtDA for metastatic colorectal cancer of added value.

-

•

Information on treatment harms and benefits was insufficiently balanced.

-

•

Future implementation requires more focus on PtDA use supporting all steps in SDM.

1. Introduction

Systemic therapy is the primary treatment for patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). When patients are able and willing to receive systemic therapy, treatment is most often aimed at extending life while improving or maintaining quality of life. Over the past years, systemic treatment options, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and their combinations, have increased [1]. Since treatment goals and the expected impact on quality of life differs per patient, a shared decision-making (SDM) process between the medical oncologist and patient is needed to align the treatment plan with patient preferences and values. Research has underlined the positive outcomes of SDM in terms of benefits for patients, including improved understanding, satisfaction, trust, treatment adherence and health outcomes [2,3]. Patient decision aids (PtDAs) are effective interventions to support patient involvement in health care decisions [[4], [5], [6]].

Although enhancement of SDM has been a key objective in Dutch health policy for years [7], SDM is still insufficiently experienced by cancer patients during treatment decision making [8,9]. In 2015, a PtDA for Dutch patients with mCRC was developed by experts in the field. This mCRC PtDA included treatment decisions for first and subsequent lines of systemic treatment or best supportive care. The PtDA was created in such a way that it supports all stages of the SDM process [3,10]. After development and usability testing, initial implementation in 11 hospitals was successful and satisfaction rates were high [11]. However, use (i.e. reach) of the PtDA declined over the years to 181 PtDAs handed out in 15 hospitals in 2020 without evidence to suggest a corresponding decrease in eligible patients. Moreover, further adoption by additional hospitals proved difficult. The challenge of implementing PtDAs in daily clinical practice is widely acknowledged [[12], [13], [14], [15]]; only 21% of PtDA researchers indicate integration in routine clinical care following their trials [16]. One of the most frequently reported barriers for integration – in implementation science more commonly referred to as sustainability [17] - is PtDAs becoming outdated. It was therefore suggested to update PtDAs alongside clinical practice guidelines [18]. In 2021, a new Dutch mCRC treatment guideline was published [19], and a nationwide SDM campaign was launched. Hence, we set out to improve the sustainability of the mCRC PtDA by evaluating real-world experiences, such as PtDA acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, and fidelity to optimize the PtDAs design and content. In addition, we gained insights in improvement of future implementation.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

In a qualitative study, we explored the following research questions: 1) What are the needs and preferences of medical oncologists and patients with mCRC regarding the (use of the) mCRC PtDA in daily practice? And, 2) How can this best be addressed in the development of an improved version of the mCRC PtDA - from here on referred to as the mCRC PtDA v2.0 – and its implementation strategy? The needs and preferences of users were uncovered using semi-structured interviews until data saturation was reached. In addition, we conducted exploratory interviews with ‘non-users’. Subsequently, a Dutch steering group of 15 experts discussed the results and devised improvements based on experience, International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) collaboration recommendations [15,[20], [21], [22]], and literature review.

2.2. The mCRC PtDA v1.0

The mCRC PtDA v1.0 is designed to discuss systemic treatment options and best supportive care with patients who are diagnosed with mCRC and visit a medical oncologist in the outpatient clinic. The PtDA is suitable for both patients who are systemic treatment naïve, and patients who are already being treated, however need re-discussion of subsequent treatment options as a result of treatment toxicity or disease progression. The PtDA consists of 3 components to support the SDM process:

-

1.

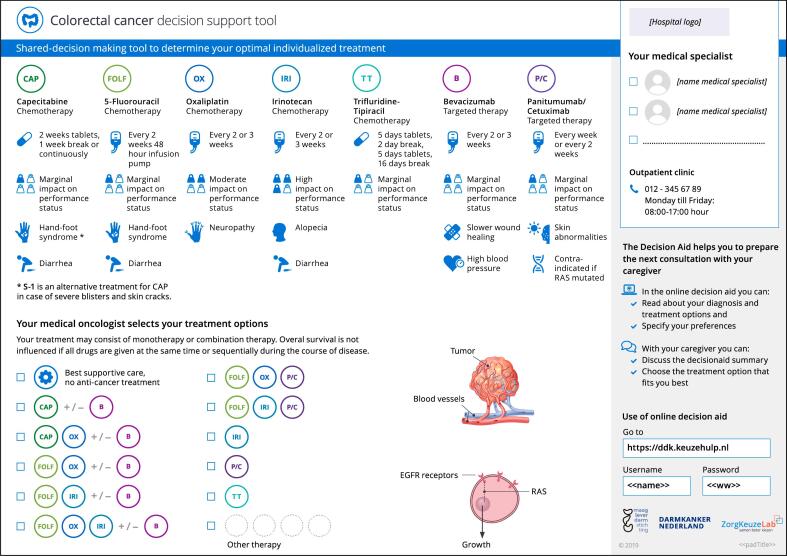

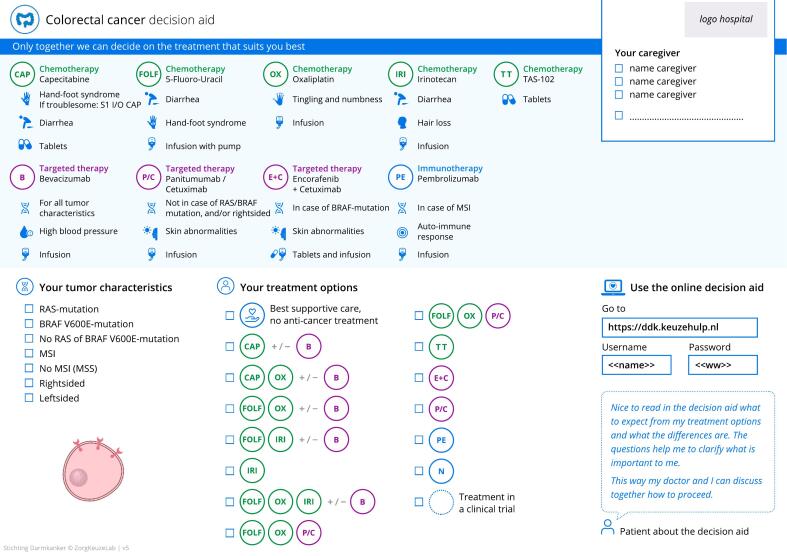

During the first treatment discussion consultation – i.e., the team talk [10] – the medical oncologist uses a one-page consultation sheet to inform the patient about the choice that needs to be made regarding treatment. (Fig. 1) In this consultation, the individuals' treatment options are indicated (check boxes), and the possible benefits and risks of those options are discussed. Moreover, the importance of the patients' involvement in decision making, and the online part of the PtDA, are explained.

-

2.

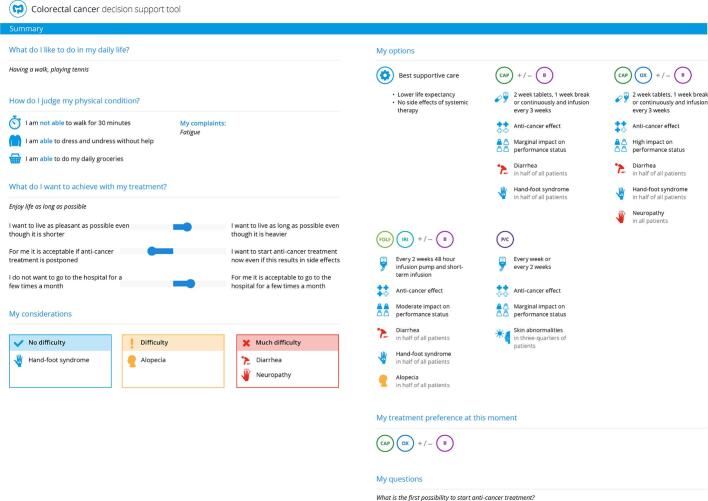

Time-out: Subsequently, the patient is provided time to deliberate the personalized treatment options at home. For this deliberation process, the patient - and their relatives - can access the online part of the PtDA through a website using a unique login code. (Supplementary fig. 1) The website contains background information on mCRC (treatment), information on treatment options (the patient is instructed to limit information to the treatment options that were indicated by the medical oncologist), and an explicit value clarification exercise to assist in making a value-congruent choice. Patients' answers and the patients' treatment preference are listed in a summary to be downloaded and/or printed by the patient. (Fig. 2)

-

3.

Decision talk: In following consultation(s), the patient and medical oncologist use the downloaded/printed PtDA summary as a supporting tool to reach a shared treatment decision based on informed preferences.

Fig. 1.

The mCRC PtDA v1.0 consultation sheet.

Fig. 2.

The mCRC PtDA v1.0 summary.

2.3. Semi-structured in-depth interviews

Between December 2020 and February 2021, seven medical oncologists with user experience were invited for the in-depth interviews. Invited medical oncologists were known to use the PtDA to different extents. The invitation addressed the aim, the interview topic, and its duration. Simultaneously, patients were recruited by medical oncologists of 2 academic and 2 community hospitals. They provided eligible patients – i.e., Dutch speaking adult patients with mCRC who received the PtDA in the previous year – with an information letter. One researcher (SN) phoned patients to obtain informed consent. Thirteen interviews were scheduled through video-calls between January and May 2021. In preparation, participants were asked to review the mCRC PtDA v1.0. The interviews were held by one researcher (SN), who did not have a treatment- nor collegial relationship with the participants, and addressed two main topics: (1) experiences using the PtDA, i.e. appropriateness, feasibility, and fidelity, and (2) PtDA content acceptability. The interview guide was drawn up by three researchers (SN, HVP, AM), was cross-checked by another researcher (MK), and was based on the ‘Measurement Instrument for Determinants of Innovations’ (MIDI-model) [23]. The MIDI-model was designed specifically for the healthcare setting based on a systemic review and Delphi study, and can be used to improve understanding of critical determinants that may affect implementation to better target implementation strategies. Each interview lasted approximately 1 h. Researcher SCN experienced saturation of reported areas for PtDA improvement during these scheduled interviews. To gain additional knowledge on motivation and barriers for PtDA adoption, five exploratory interviews were scheduled and conducted by SCN with ‘non-users’, i.e. 2 patients, 2 medical oncologists, and 1 oncology nurse. These interviews were also coded and discussed by researchers HVP and SCN.

2.4. Data analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. First, all transcripts were read by two researchers (SN, HVP) to understand the meaning of the whole text and to inductively identify relevant themes. These researchers were not involved in primary development and/or implementation of the PtDA nor were they users of the PtDA. They then coded three transcripts to form an initial and shared understanding on coding, which was based on the MIDI model. Conflicting perspectives – i.e., some determinants left room for ambiguous interpretation, or were considered to relate to a single underlying construct - were discussed until consensus was reached. In accordance with previous studies [24], the extent to which the mCRC PtDA adhered to the treatment guideline, was categorized as an extra determinant within the domain socio-political context. All interviews were analyzed using the final codebook by one researcher (SN or HVP), with reliability checks of all interviews performed by the other. After coding, data saturation was confirmed by researcher HVP.

2.5. Continued development by the steering group

The steering group consisted of fifteen experts: eight medical oncologists with mCRC expertise of whom four had mCRC PtDA v1.0 user experience, two specialized oncology nurses, a patient representative of the Dutch CRC patient association, a representative of the Dutch Digestive Association (MLDS), two PtDA development experts and one medical researcher. The steering group held five meetings between January and December 2021. During the first meeting the experts redefined the scope and purpose of the PtDA and outlined what information was outdated based on the newly published mCRC treatment guideline. In later meetings, interview results, personal perspectives and IPDAS recommendations were discussed to formulate improvements and develop the mCRC PtDA v2.0. [15,20,22].

3. Results

The six participating patients with user experience (83% male) represented several age-groups, diverse levels of education, and used the PtDA for either first- or later-line treatment decisions. Four patients (67%) had used the PtDA in the three months prior to the interview. Most medical oncologists had at least five years of professional experience. Five medical oncologists (71%) were active users of the PtDA. (Table 1) Characteristics of the five exploratory interview participants without user experience are presented in supplemental table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of in-depth interview participants with user experience.

| Characteristics | Patients with mCRC n = 6 (%) |

Characteristics | Medical oncologists n = 7 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, range in years | 44–79 | Age, range in years | 35–56 |

| Gender | Gender | ||

| Male | 5 (83) | Male | 4 (57) |

| Female | 1 (17) | Female | 3 (43) |

| Level of education⁎ | Practice setting | ||

| High | 2 (33) | Academic hospital | 0 (0) |

| Intermediate | 0 (0) | Teaching hospital | 6 (86) |

| Low | 2 (33) | Community hospital | 1 (14) |

| Unknown | 2 (33) | Years of mCRC experience | |

| Time since use of the PtDA | Range | 2–19 | |

| <6 months | 5 (83) | ≤5 | 2 (29) |

| >6 months | 1 (17) | >5 | 5 (71) |

| mCRC PtDA usage | mCRC PtDA usage | ||

| Did use the online PtDA | 2 (33) | Current | 5 (71) |

| Did not use the online PtDA | 4 (67) | Past | 2 (29) |

Levels of education were based on the definition of Statistics Netherlands (CBS) for which the International Standard Classification of Education form the basis. The lower education level includes groups 1 through 8 (all years) of primary and special primary education plus the first three years of senior general secondary education (HAVO) and pre-university secondary education (VWO); the various pathways of prevocational secondary education (VMBO) including lower secondary vocational training and assistant's training (MBO-1). The intermediate education level includes upper secondary education (HAVO/VWO), basic vocational training (MBO-2), vocational training (MBO-3), and middle management and specialist education (MBO-4). Higher education refers to associate degree programs, higher education (HBO/WO) Bachelor programs; 4-year education at universities of applied sciences (HBO); Master degree programs at universities of applied sciences and at research universities (HBO, WO); and doctoral degree programs at research universities (WO).

3.1. Overall experience using the mCRC PtDA v1.0

Both patients and medical oncologists confirmed the PtDA to be a relevant tool to support treatment decision making in mCRC. According to patients, use of the PtDA made them, and their relatives, feel well and transparently informed, well prepared, involved, and conscious of their own values and preferences. “Assessing the information and deciding what's important to you is a very personal process. After using the online PtDA, I had a clear understanding of my thoughts on the matter… My spouse and I were well-prepared and able to discuss the things that really mattered.” (Patient 1, 68 years old) Most medical oncologists stated that use of the PtDA was of added value due to better structured consultations, more involvement of patients, facilitation of end-of-life care discussion and time reduction in follow-up consultations. They experienced that patients were more satisfied and in control, more aware of their prognosis, and more confident about the chosen treatment. (Table 2) The two medical oncologists who no longer used the PtDA (‘former users’) had perceived insufficient added value relative to the effort required to change practices. Both expressed reluctance to use the PtDA due to concerns that it could lead to preferences inconsistent with their recommendation. “You've got your own preference. I've only used the PtDA to a limited extent because the times I thought about it, I decided not to because it had to be monotherapy [the most conservative treatment] anyway.” (MO 6, former user).

Table 2.

Experiences with the mCRC PtDA v1.0 of patients (P) and medical oncologists (MO).

| Determinants MIDI model⁎ | Patients (P)# | Medical oncologists (MOs)# |

|---|---|---|

|

MOs find the instructions for using the PtDA clear. The method of use varies, however. The consultation sheet itself is explained to patients, but patients are not pointed towards the online PtDA as a matter of course. There is not always a time-out and the PtDA does not always come up in follow-up conversations. | |

| “The information sheet is not overwhelming, but it is important that the doctor guides you through the content.” (P 2) “I found my doctor's explanation with that sheet very helpful, and I appreciated that I had a say in the treatment choice. At the end of the consultation, I asked my doctor what treatment she thought was best for me, and my wife and I agreed with her recommendation. Although she mentioned the option to use the website, I decided not to because I prefer to take things as they come.” (P 3) “No, my doctor didn't say that I could use an online PtDA. I did get that leaflet, but I didn't log in to a website.” (P 6) | “I don't often use the summary in practice, but I think I'll have to push patients a bit more towards that online PtDA.” (MO 2) “I discuss everything, tick the suitable treatment options, refer them to the website and say we'll come back to it in the next consultation.” (MO 5) “If it's straightforward, they make a choice right away during the first appointment. In practice, people don't want to think long about it at all; they want to start treatment as soon as possible.” (MO 6) | |

|

Some texts in the online PtDA are considered outdated as a result of the new treatment guideline. MOs indicate that the effect on physical performance, as mentioned on the consultation sheet, is not correct for combinations of drugs. MOs emphasize that regular updates of content are essential. | |

| “The PtDA gives a summary and shows the correct side effects. That's also been my experience.” (P 2) | “The consultation sheet shows the effect on physical performance for each individual drug, but that's not correct when combining drugs.” (MO 6) | |

|

MOs feel that there is not enough information about biomarkers, study participation and differences in treatment option effectiveness in the PtDA. Patients need more information about treatment effectiveness for an informed choice, and desired information on the biomarkers, experimental trials, recommendations on lifestyle and diet, manageability of side effects, as well as references to reliable sources. | |

| “I miss having an explanation about how many courses someone gets on average. And what it gives you, in terms of time… and how side effects can be partially managed by reducing the dosage, for example.” (P 1) “I was a little bit afraid that I was going to pick based on side effects and not based on the effect of the treatment on my cancer.” (P 5) | “You could add something about the possibility of experimental treatment. Because some of the people that have no regular treatment options left, are still in very good shape.” (MO 5) “I think that you need to emphasize what exactly a treatment adds, for example by listing differences in effectiveness between treatments without showing exact numbers.” (MO 6) | |

|

Choosing treatment is considered complex in general due to uncertainty about prognosis and side effects. Some MOs think it is unhelpful that the consultation sheet presents treatment options that are not a good option for every patient. They would prefer a more personalized or hospital specific consultation sheet. Patients think the names of the medications are difficult, but the abbreviations, texts, and pictures in the online PtDA are easy to understand. At first, the PtDA offers a lot of information, however the consultation sheet is useful as a reference guide and the online PtDA can be read in stages. | |

| “In my opinion, not telling the patient that there are treatments unavailable to you due to a certain mutation is not an option. You will hear about those treatments anyway.” (P 2) “You can pick the items you want to read. The latter is valuable because I didn't want to know everything. (P 3) “The information was easy to understand, but it's still difficult to make the choice all by yourself. I mean, you can say it would be awful to lose your hair – but what are you going to do about that cancer then?” (P 4) “When you come back from talking to the doctor, you're so tired… So, you put it all aside and think it can be dealt with later.” (P 6) | “If you also have to cover all kinds of nonsensical treatment options, it's too much information, too much noise.” (MO 3) “I'd like to see a centre based, individualized PtDA. Because we never use FOLFOX, for example, I would remove it entirely.” (MO 5) “I struggled a little with the best way to use it and at what point in the conversation. Putting the consultation sheet on the table straight away didn't work in my experience; now I start the conversation organically and bring it out when visual support is needed.” (MO 7) | |

|

Whether their practices need to be adjusted depends on the MOs consultation style and the clinical care pathway. A time-out is unusual in most hospitals, but easier to implement in some than others depending on how common it is to have a second moment of contact with a patient before starting treatment. MOs state that not all patients want to be involved in the decision making nor want to further consider options at home; they ask the doctor what to do and/or want to start treatment soon. | |

| [Only applicable to MOs] | “Some patients are clear about their wishes and do not need a second consultation. Other than that, the PtDA complemented the way I work, so not much had to change.” (MO 2) “The PtDA didn't add anything to my working method, except that I had to adapt… But I sincerely believe that it would benefit many doctors.” (MO 3) “It's convenient that we have to wait a week for the DPD result anyways, so you can use that time to let the patient reflect.” (MO 5) “The PtDA required some changes in my communication techniques, but once I got that hang of that, it was a great asset. […] The PtDA forces you to take a time-out. I also started doing that more in patients with other types of cancer.” (MO 7) | |

|

Patients feel it would be useful if the MO read their answers to the questions in the online PtDA, or receive their PtDA summary, beforehand. MOs notice effects of using the PtDA. | |

| “I think it would be nice if your doctor has already read your answers beforehand. So, you can dive deeper into it straight away.” (P 2) | “I wasn't a fan of PtDAs: I thought I don't need them because I already work that way. But we decided to do the pilot and it made me very enthusiastic.” (MO 5) | |

|

Almost all MOs confirmed that mCRC patients have a choice. They also feel it is relevant that the PtDA subtly encourages people to think about the end of life. Some MOs think the PtDA (mostly the online part) is not relevant for everyone, especially because some patients do not want to have an active role in decision making. Patients feel it is useful to think about what is important to them and to share that with their MO. The need to have a say in treatment choices varies with the patient. | |

| “Assessing the information and deciding what's important to you is a very personal process. After using the online PtDA I had a clear understanding of my thoughts on the matter.” (P 1) “Listen: she's the oncologist and should decide what to do, but I liked being able to do that together. Look together at what would be good for me and when.” (P 3) “Making a choice isn't something I really see as an option: she's the specialist and has loads of experience and I trust that.” (P 4) | “I still sometimes notice, with older patients in particular, that they have difficulty with the concept of shared decision-making.” (MO 1) “In the past, patients didn't have so many choices but now you have several at any point in treatment.” (MO 5) “People in this region really have no idea and they say, ‘You're the doctor, you're the one who's trained for it, so you decide.’” (MO 6) “With the PtDA patients feel more in control and stand behind their choices. That's important for coping. Besides, the consultation sheet really is a concise reminder.” (MO 7) | |

|

MOs feel that the PtDA is a good conversation aid. The PtDA improves joint decision-making, helps give the patients more control and makes it easier to discuss the do-not-treat option, future treatment choices and the last stage of life. Moreover, some MOs stated that the PtDA saves time once they have got the hang of the method. Patients say they feel engaged and more aware of their situation. The PtDA helps them structure their thoughts and talk to their doctor about what really matters. Moreover, the PtDA also helps those close to them and offers transparency. Disadvantages mentioned by some of the MOs were that they had to adapt their working methods and that explaining treatment options that they felt were not (yet) relevant was undesirable. Patients listed the disadvantages as being that the questions in the decision aid can be confrontational, and that receiving more information than desired by the patient can be a source of worry. | |

| “My wife and I came prepared, and we were able to dive straight into the deep end with my doctor.” (P 1) “For trust, it's good that all treatment options are listed transparently. […] And that answering those questions makes you a human being to your doctor.” (P 2) “I skipped that question about living as pleasantly as possible versus living as long as possible, but it is a question that needs to be asked.” (P 4) “It's nice in a way that you get more explanation, but on the other hand it also makes you worry more. I'd rather be given a single sheet of paper saying what the doctor wants to do.” (P 6) | “With the PtDA, you can easily explain the options, including the option of doing nothing. […] It helps reach a joint decision. And giving the patients some control helps throughout the treatment pathway.” (MO 2) “It gives some continuity: in subsequent treatment choices, you are back at the table with the same information. On top of that, it helps the patient see that it can't go on forever, and that helps me too.” (MO 4) “I've only used it to a limited extent, because the times I thought about it, I then decided I shouldn't because it had to be the most conservative treatment anyway.” (MO 6) | |

|

The PtDA makes it clear that there are options and gives patients tools to help them decide. Most MOs do not get the impression that patients make different choices when using the decision aid; it's rather a case of them standing more squarely behind the choice made. | |

| “This one was the best, but I could also choose the one where your hair falls out. I could have said I'd rather have my hair fall out than have rashes and itching all over my body.” (P 6) | “The other day, I had an eighty-year-old patient who only realized after going through the online PtDA that he wasn't going to get better.” (MO 2) “The patient's initial idea isn't necessarily changed by the PtDA; if they feel more in control, they're more likely to continue the treatment. And if a patient picks a less severe treatment themselves, they're also less surprised when it stops working; conversely, if they decide to bite the bullet, they won't blame me for it being tough.” (MO 7) | |

|

The way MOs and patients perceived their tasks varies. There are MOs who say they leave the choice to the patient as much as possible and others who believe that a patient cannot make the best treatment choice themselves. The same goes for patients: some leave the choice up to the doctor and others prefer to decide for themselves. Assistance from the doctor in joint decision-making is not always highlighted and deserves attention in the implementation. Not all doctors see it as their job to tell patients about treatment options they do not think are good options or to discuss the summary when the treatment choice has already been made. | |

| “I think that the doctor should be in control. If you create the impression that the patient must decide, that creates too much responsibility and confusion.” (P 1) | “The PtDA is an improvement in quality of care. Shared decision making, modern times. You should be a part of that.” (MO 2) “I always try to leave the decision with the patient: You have the final say about what it's going to be. People should always have a choice.” (MO 6) | |

|

The consultation sheet is discussed together during the consultation. It is not standard for a patient and/or those close to them to log into the online PtDA. Patients infrequently bring the summary along to the next consultation. Both logging in and using the summary seem to depend partly on what the MO says about doing so. | |

| “I did still go through the PtDA out of curiosity but didn't fill it out in detail because we'd actually already made up our minds.” (P 2) “No, we didn't bring that summary along. It might well have been discussed over the phone, though – I don't remember.” (P 4) | “Patients often come back with that consultation sheet off their own bat later in the treatment process.” (MO 2) “I always recommend logging in and I actively point them towards the website. I reckon that does help: if you just point out that they can login, then maybe people won't do it.” (MO 5) “I tell them to bring the summary with them if they want me to be able to see what they've filled in. Less than half the patients bring it along, but I don't consider that a problem because I prefer it anyway when they just tell me.” (MO 7) | |

|

The PtDA lets those closest to the patient offer their support. On top of that, the PtDA is also a nice reference guide for them. | |

| NB: only applicable to P | After using the online PtDA, my spouse and I were well-prepared and able to discuss the things that really mattered.” (P 1) “I showed the sheet to my daughter, and she looked everything up and explained it to our son. They are better at using the internet.” (P 3) “My wife was with me at the first consultation, and she explained everything to me using the sheet afterwards.” (P 4) | |

|

The PtDA is usually used by multiple MOs at the same hospital. Sometimes not every MO continues use. Nurses can also be the initiator to implement the PtDA in an oncology department rather than an MO. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “I was the only one who started using the PtDA at first with any enthusiasm.” (MO 4) “My colleague uses it too, every time the course of treatment changes.” (MO 5) “The pictures that are on the sheet aren't a nuisance, but I never use them. Though I do know that some of my colleagues do.” (MO 7) “At the time, it was a nurse who introduced the PtDA at our hospital. We continued with it because we felt the pilot worked well.” (MO 7) | |

|

Most MOs think they already handle joint decision-making properly, but the quotes show that assisting the patients in weighing up the pros and cons, particularly to turn an initial treatment preference into an informed treatment preference, is not always routine yet. Some patients feel they cannot participate in decision-making because they don't have the knowledge, or that the responsibility of having to choose leads to them worrying about making the wrong choice. This again revealed that patients do not feel to have received enough information about the effects of treatment. | |

| “It would be bad if people are anxious about all kinds of side effects that may not happen and then make the wrong choice.” (P 1) “I sometimes fear that I will be seen as too critical. It's not that I don't trust the treatment I'm offered, but still, you wonder what else is out there.” (P 2) “As a patient, you can't really choose because you don't know all the ins and outs. A doctor's been trained for that, though. I could have said, ‘I'd rather not have my hair fall out’, but she thought the one I'm getting now was the best for me, so then I have to listen to that of course. The point is that it should also have an effect. […] Maybe we trust the doctors too much. That might have something to do with our age.” (P 6) | “I think the process of shared decision-making does go reasonably well but I'm also aware of where it can be improved.” (MO 1) “I always remind myself that the patient must be in control, and I try to provide people with the best possible information. But sometimes, as a doctor, you must be honest when you feel that the medical side no longer has any point for someone; that is also shared decision-making.” (MO 2) “I think I am very good at shared decision-making. I may be someone who comes across as overwhelmingly direct. Almost everyone appreciates that, but some people may be a little too directed for their liking. With those patients I consciously try to plan that second appointment.” (MO 4) | |

|

The annual subscription fees that are paid for the PtDA are used to update content and send feedback on PtDA use and anonymous patient feedback to medical oncologists. Budget needs to be made available by the medical oncologists/the hospital itself. Current users believe that the costs are reasonable, however the costs might be a barrier for hospitals to implement the PtDA, especially when they would like to implement multiple PtDAs. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “I reckon the costs weigh up okay against the quality you offer with the PtDA. If this lets them make better choices, I think that you'll save money in turn that way, perhaps also by them experiencing fewer side effects with a treatment that really suits them.” (MO 2) “If you want it to be used as often as possible in oncology in the Netherlands, it is better if no financial compensation is required. Because that, by definition, puts up barriers.” (MO 4) | |

|

Using the PtDA does not seem to cost oncologists more time, although that is sometimes the expectation beforehand. Busy schedules can be a barrier to implement the PtDA or the time-out and change usual workflow. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “I didn't always get around to including the PtDA, given the hectic pace of such a consultation, but my consultations didn't take any longer when I did use it.” (MO 3) “The tool saves me time because people also know what is coming next. They sometimes even say it themselves: right, so we're moving on to…” (MO 5) | |

|

The PtDA sometimes gets forgotten if it is not readily available in the consultation room. Internet access is a limiting factor for some patients to use the online PtDA. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “There are people who don't have internet and therefore don't use the online PtDA, but they do benefit from the pictures and the consultation sheet.” (MO 5) “Because I was in a variety of outpatient clinic exam rooms and see a range of cancers, I didn't always have that consultation sheet to hand.” (MO 6) | |

|

A coordinator is appointed at start-up but may not retain an active role after implementation. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “One of my colleagues was the coordinator; they implemented the PtDA at the time. It is just an assumption that she then took it further.” (MO 2) | |

|

Some doctors receive feedback on the use of the PtDA. This feedback is not always shared or discussed with the whole team. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “I get these overviews and look at how many PtDAs I've handed out. My colleagues don't get those.” (MO 2) | |

|

Some information in the PtDA was outdated as a result of new research findings. The PtDA would be more in sync with recommendations in the newly published mCRC guideline by including information on molecular diagnostics and new treatment options. MOs agreed that only available and reimbursed diagnostics and treatments should be featured in the PtDA. | |

| NB: only applicable to MO | “Patients are often confused about mutation analysis and the use of agents that work with antibodies. So, explaining that visually in the new version would help.” (MO 4) | |

Definitions of determinants used, based on the MIDI model [23]; Procedural clarity: ‘the extent to which the procedure to use the PtDA is clear’, correctness: ‘the extent to which the information in the PtDA is correct’, completeness: ‘the extent to which the information in the PtDA is complete’, complexity: ‘the extent to which the PtDA is complex to use’, compatibility: ‘the extent to which the PtDA is compatible with work methods’, observability: ‘the extent to which the effects of the PtDA are visible’, relevance: ‘the extent to which the PtDA is relevant for the patient’, personal benefits/drawbacks: ‘benefits/drawbacks of PtDA use’, outcome expectations: ‘outcome expectations of users’, professional obligation: ‘the degree to which responsibility is felt to use the PtDA’, patient cooperation: ‘the extent to which the patient cooperates with PtDA use’, social support: ‘support experiences to use the PtDA’, descriptive and subjective norm: ‘PtDA use by- and motivation of co-workers’, self-efficacy: ‘degree to which the user believes he or she applies shared decision making (using the PtDA)’, financial resources: ‘availability of financial resources needed to use the PtDA’, time (available): ‘availability of time to use the PtDA’, material resources: ‘availability of recourses necessary for the use of the PtDA’, coordinator: ‘the presence of one or more persons responsible for coordinating use’, performance feedback: ‘received feedback on implementation progress’, adherence to clinical guidelines: ‘adherence of the PtDA to the new guideline’.

Note that this table is limited to the 13 interviews with participants with user experience; all quotes have been translated from Dutch to English.

3.2. Content - what could be improved?

Multiple patients struggled to establish their treatment preference based on the online PtDA due to insufficient information on treatment effectiveness compared to treatment harms. As one patient stated: “What is important to me are the side-effects and the treatment effect. Is one therapy better than the other? That's what I missed in the decision aid. […] I was a bit afraid that I had to choose a treatment based only on side effects.” (Patient 5, 47 years old) (Table 2). Additional unmet information needs that were identified included: a) newly available treatment options; b) molecular biomarkers, c) treatment within an experimental trial, d) recommendations on lifestyle, diet and side-effect management, and e) links to reliable sources. Medical oncologists disagreed with the presented ‘effect on physical performance’ for each separate drug on the consultation sheet, and most expressed a preference for a more patient and/or hospital specific sheet, presenting not all, but only a selection of the guideline recommended treatment options. Two rationales were expressed; Some believed that explaining impossibilities is not helpful for patients and costs time that could be better spend. Others feared that the consultation sheet could become overwhelming as treatment options increase. In contrast, one patient explicitly expressed appreciation of also being informed about mCRC systemic treatment options that were unsuitable in her situation. Medical oncologists agreed that medical information in the PtDA was partially outdated and supported the steering group's pre-proposed adjustments based on the newly published treatment guideline.

3.3. Implementation - what could be improved?

Amongst experienced users, we identified barriers for implementation at different levels (Table 2). Firstly, the PtDA was not always used as intended by its developers (i.e. fidelity). Most medical oncologists explained to be selective in handing out the PtDA, and irregularly discussed the online PtDA and summary with patients. The most frequently cited reason was that preferences can be sufficiently clarified during the first consultation, and that many patients ask the medical oncologist to decide, amongst other reasons to start treatment as soon as possible. Patients were found to be less inclined to use the online PtDA when; (1) their information needs and/or internet skills were limited, (2) they were not instructed to login at home, or (3) the treatment decision was already made. “I found my doctor's explanation with that sheet very helpful, and I appreciated that I had a say in the treatment choice. At the end of the consultation, I asked my doctor what treatment she thought was best for me, and my wife and I agreed with her recommendation. Although she mentioned the option to use the website, I decided not to because I prefer to take things as they come.” (Patient 3, 79 years old) Users also experienced personal implementation barriers. At initiation of use, it required effort for medical oncologists to adapt their practices. Moreover, some felt reluctant towards presentation of treatment options on the consultation sheet that may be unsuitable for the individual patient. Packed outpatient clinic schedules, limited consultation time and fear of confusing patients appeared to underlie these barriers. At the patient level, some reported feeling incompetent, or fearful of making a wrong decision.

We additionally identified system and cost barriers. The PtDA consultation sheet was not always available in the consultation room. Moreover, the planning of a time-out was not customary nor considered easy to implement in the care pathway due to limited availability of consultation time. Since subscription to use the mCRC PtDA currently costs ±3000 euros per hospital per year without availability of funding support, financial constrains were reported to be a complicating factor for use, especially given the number of indications for which PtDAs are now available.

3.4. Adoption – insights of ‘non-users’

In the exploratory interviews with participants without user experience, both patients did not express dissatisfaction with the decision-making process; however, they did emphasize the personal relevance the PtDA could have had earlier in their treatment trajectory. “My oncologist presented a clear treatment plan with the treatment goals. I don't recall her discussing any options and I didn't ask about choices either; I assumed that what she told me would be best. […] I don't believe this would have impacted my choice; however, it would have been useful information, and I would have definitely logged on to that website.”

Both medical oncologists were aware of the availability of the PtDA prior to the interview invitation. They recognized that patients with mCRC have choices regarding treatment, however expressed doubt whether some degree of paternalism is undesirable for patients in this complex setting. Besides the financial cost and outdated PtDA content, additional barriers for adoption were brought up: They assumed limited added value - seemingly related to confidence in decision-making quality - and expressed concern that, for most patients, the PtDA provides information on too many options too early, which could result in confusion and misinterpretation by patients and their relatives. Upon further inquiry, local preferences regarding treatment, and fear of causing stress by transferring choice responsibility were also reported. Interestingly, the participating oncology nurse was highly motivated to use the PtDA and acknowledged to have experienced busy schedules to be a barrier in engaging and motivating the medical oncologists working in her hospital. Importantly, she judged it feasible to conduct the second consultation herself: “At the moment, the medical oncologist recommends a treatment (often CAPOX), and patients simply seem to follow that recommendation. […] I think that the consultation in which the summary is discussed could also be performed by oncology nurses. As nurses, we have a lot of experience with these treatments and value that patients make more informed decisions. If needed, we can always reinvolve the medical oncologist.”

3.5. Development of the mCRC PtDA v2.0

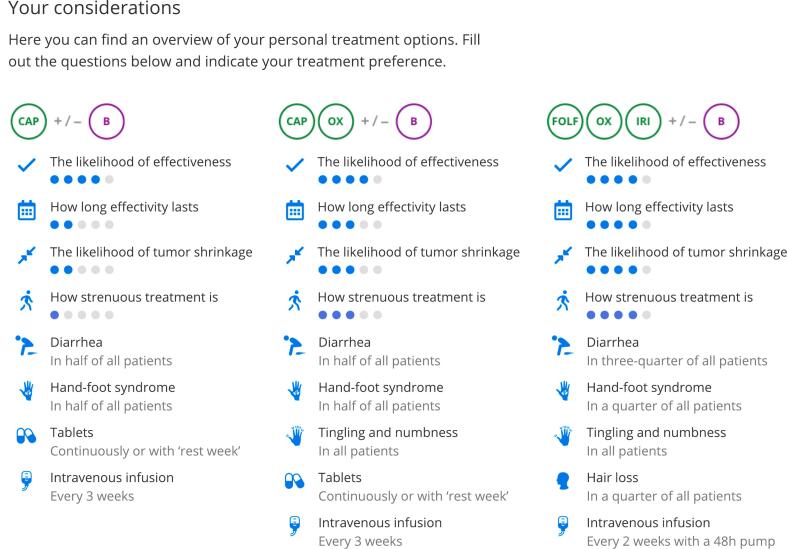

In May 2021, the results of the in-depth interviews were discussed and key improvements for PtDA content were defined by the steering group. (Table 3) The additional effectiveness outcomes to be presented for each treatment option (‘likelihood of effect’, ‘duration of effect’, ‘likelihood of tumor shrinkage’) were based on expert opinion and exploratory evidence review [22]. (Fig. 3, supplementals; Fig. 2 and Table 2) Additional texts were written, and the entire PtDA was redesigned. (Fig. 4) Four steering group members (SN, MK, AM, RT) devised recommendations for future implementation. These were created using recently published key strategies formulated by the IPDAS group based on data from 23 implementation studies, combined with our own insights that were built on the interview results for this specific oncology setting (Table 3) [15]. In September 2021, the steering group finalized the mCRC PtDA v2.0 prototype, and usability testing was performed. Apart from design adjustments to improve user-friendliness, no major revisions were needed, and no additional needs were identified. In February 2022, the mCRC PtDA v2.0 was launched in 15 hospitals with an existing subscription.

Table 3.

Summary of improvements formulated by the steering group for mCRC PtDA v2.0.

| PtDA content |

| 1. Add systemic treatment options (encorafenib-cetuximab and pembrolizumab) to the consultation sheet and online PtDA. 2. Add information on biomarkers (BRAF, RAS, MSI vs MSS) and sidedness to the consultation sheet (check boxes) and online PtDA. 3. Remove ‘effect on physical performance’ for separate drugs on the consultation sheet. 4. Redesign the consultation sheet to maintain oversight and highlight the website login information to increase awareness. 5. Add to the online PtDA:

6. Optimize value clarification exercises and questions in the online PtDA to increase usability of the PtDA summary. 7. Redesign the flow of the online PtDA and rewrite texts for optimization of comprehensibility. 8. Redesign the PtDA summary based on the new content of the online PtDA. |

| PtDA implementation strategy |

Enhance adoption across the Netherlands:

1. Appoint a clinical leadership team, consisting of one medical-oncologist and one (specialized) oncology nurse. 2. Schedule an introductory meeting with the leadership team:

3. Provide the leadership team with a summary of what was discussed in the introductory meeting to present to all team members. 4. Send every team member a personal username and password for the online PtDA, followed by an inquiry of feedback on content. 5. Organize a live local kick-off meeting with all team members shortly before starting implementation:

6. Send monthly overviews of PtDA use and voluntarily obtained patient satisfactory. Inquire after feedback from the local team. 7. Organize an evaluation meeting after ±five months to discuss feedback provided by patients and experiences of the local team. If needed; make changes to workflow or task delegation. |

Fig. 3.

Overview of a patients' personal treatment options in the mCRC PtDA.

Fig. 4.

The mCRC PtDA v2.0 consultation sheet.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

To improve sustainability of the Dutch mCRC PtDA v1.0, we examined real-world experiences of patients and medical oncologists. In addition to the desired update of PtDA content according to the new treatment guideline, we identified unmet information needs regarding molecular biomarkers, experimental trial participation, diet- lifestyle- and side-effect management, and most importantly: treatment effectiveness. Several medical oncologists' expressed concern about the number of treatment options on the consultation sheet and suggested to make it center-specific or patient-individualized. Some oncologists disliked the need to address ill-suited treatment options. Findings that require most attention during implementation in individual hospitals were selective distribution and limiting use to the consultation sheet, hence not supporting deliberation at home. Moreover, continued SDM education and a sustainable funding model are needed to achieve adoption of the PtDA across the Netherlands. The steering group devised key improvements and developed the mCRC PtDA v2.0 accordingly.

To prevent harmful bias, PtDAs should present equal details on negative and positive features of treatment options [21]. Although both were addressed in the mCRC PtDA v1.0, the information was found to be unbalanced. Numerical outcome probabilities, such as survival benefit, are recommended to be used in PtDAs [22]. However, the steering group decided to use graphical outcome information to limit risk of treatment effect over- or underestimation as available mCRC systemic treatment outcomes are known not be representative of outcomes in the general mCRC population; they stem from clinical trials often including younger and more fit patients [25,26]. This phenomenon is commonly referred to as the efficacy-effectiveness gap [27]. During consultation, a medical oncologist can provide the individual patient with additional numerical information on expected outcomes when desired [26]. Our future goal for the PtDA is to provide patients with customized advice based on real-world treatment outcomes of Dutch patients collected within the Prospective Dutch CRC cohort [28].

We encountered discrepancies between users in the desire for a consultation sheet that presents only a selection of the available treatment options versus all treatment options recommended in the Dutch guideline. Patients did not confirm medical oncologists' concern of the consultation sheet being overwhelming, nor did they confirm futility of having been presented with treatments that were unsuitable in their situation. On the contrary, it was cited to provide transparency. Moreover, former users' fear that patients might desire an ill-suited treatment option was not experienced by medical oncologists with longer user experience. This fear of patients choosing wrongly is a well-known barrier for implementation of SDM [29]. Since undesirable – patient-independent – practice variation in systemic treatment of mCRC has been demonstrated in the Netherlands [30,31], and no patient-derived arguments were identified to restrict the consultation sheet, the steering group decided to continue to present all guideline-recommended treatment options in the mCRC PtDA v2.0 ensuring transparency and equal information delivery across hospitals. To assist medical oncologists in addressing any unsuitable treatments in the limited consultation time available, tumor characteristics were linked to treatment options on the mCRC PtDA v2.0 consultation sheet. For example, the sheet indicates that pembrolizumab is only effective in patients with microsatellite instability (MSI) mCRC. (Fig. 4).

Concerning improvement of implementation, we discovered that some medical oncologists were selective in distributing the PtDA based on assumptions regarding preferred decision-making roles. Similar results were found in earlier studies on PtDA implementation in oncology care [[32], [33], [34]] However, Kehl et al. [35] found that positive appraisals of quality of care and communication were associated with the experience of a shared decision by colorectal cancer patients, independent of the preferred patient role. In addition to selective distribution, use of the PtDA was often limited to the consultation sheet, and treatment decisions were made during the first consultation. Although we did not evaluate consultations of participating medical oncologists, previous research has shown that values and appraisals of patients are subject of conversation in only half of consultations on palliative chemotherapy [36,37]. Therefore, we doubt whether truly value-congruent cancer treatment choices are indeed made in those situations. Specifically in oncology, SDM experts have identified time outside the consultation to be an essential part of SDM, and medical oncologists are stressed to refrain from providing a recommendation too early in the SDM process [[38], [39], [40], [41]].

Another relevant finding is patients expressing fear to choose wrongly, indicating that too much choice responsibility may currently be transferred to the patient. Our new implementation strategy will address these different findings. (Table 3) Approaches such as involvement of both medical oncologists and nurses in implementation planning and care pathway integration, and communication training on how to encourage patients to use the online PtDA without transferring decision uncertainty and responsibility, are known to improve implementation success and sustained use [15,32,34]. In addition to our efforts, a sustainable funding model for decision aids is needed to eliminate financial barriers for PtDA use and implementation. Discussion is currently ongoing between Dutch health ministry, health insurance companies, decision aid developers, patient associations, and health care providers.

Our study has several limitations, such as the possible bias in interview responses. Since the interviews with patients were conducted months after use of the PtDA, recall bias may have occurred. Moreover, patients with mCRC who are further along in the treatment trajectory – such as the participants – might express different needs compared to patients who have just been diagnosed with mCRC. And, despite our effort to minimize social-desirability bias by using an interviewer that had no treating nor collegial relationship with the participants, medical oncologists may have responded more desirably due to national attention for the use and implementation of SDM and PtDAs. Although we are aware that the PtDA is sporadically used to explain treatment options to non-Dutch patients, we did not include any, nor did we ensure participation of patients with low health literacy. Lastly, since this PtDA was actively used in daily clinical practice and our study results were planned to be promptly used for re-development purposes, we focused on improvement of PtDA design and content. Nevertheless, we believe more detailed knowledge on use of PtDAs in the oncology field is essential to formulate a successful implementation strategy and reach our goal to provide each patient with mCRC with the opportunity to make an informed decision regarding systemic therapy. Hence, we additionally conduct a mixed-methods real-world implementation study in ‘PtDA naïve’ hospitals which will substantiate user perceptions with exact measurements assessing appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility, fidelity, penetration, cost, and sustainability. In addition, this study will engage nurses, and – amongst others - evaluate experiences of patients with low health literacy and those who were recently diagnosed.

4.2. Innovation

The challenge to achieve sustainability of the use of PtDAs in clinical practice is widely acknowledged. As much of the current knowledge on PtDA implementation is derived from highly controlled settings, our study adds to the call to identify contextual factors that determine success of PtDA implementation in routine clinical care [15]. Our approach of continued decision aid and implementation strategy development has, to our knowledge, not been described before, and may encourage others to thoroughly evaluate experiences and needs several years after PtDA implementation in order to achieve sustainability. The main strength of this approach was the in-depth analysis of interviews with real-world PtDA (non-)users, focusing not only on additional needs regarding PtDA content, but also on lessons for future implementation. By using the MIDI model, we were able to provide a well-structured overview of qualitative results that were promptly used in development of the mCRC PtDA v2.0. Assumptions regarding qualitative results and suggested PtDA improvements were questioned by applying reflexive dialogue between the analyzing researchers and steering group members. Since most barriers for adoption of PtDAs seem to stem from obstacles to apply SDM principles, in addition to continued development of decision aids, we want to emphasize that continued SDM attention and education is needed to remove these barriers and align oncologists' beliefs with patients' wishes. Moreover, we believe the involvement of nurses, thorough preparation and a center-individualized approach, and repeated user-training with use of user-feedback will aid in achieving successful implementation. The strategy outlined in this paper may be used by others working to promote implementation of PtDAs.

4.3. Conclusion

PtDA's are effective interventions to support patient involvement in health care decisions, but are considered difficult to implement and sustain in daily clinical care. By qualitatively evaluating real-world experiences with a PtDA for systemic treatment of mCRC, we identified relevant opportunities for optimization of both PtDA content and implementation. Hence, we developed the mCRC PtDA version 2.0 and accompanying implementation strategy. This approach of continued decision aid and implementation strategy development may add to sustainability. Currently, a multi-center mixed-methods study evaluating implementation success of the mCRC PtDA v2.0 is ongoing.

Funding

Financial support for this project was provided by the Dutch Digestive Foundation (in Dutch: Maag Lever Darm Stichting, MLDS).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Utrecht University. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. We confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sietske C.M.W. van Nassau: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Helene R. Voogdt-Pruis: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis. Vincent M.W. de Jong: Writing – review & editing. Hans-Martin Otten: Writing – review & editing. Liselot B. Valkenburg-van Iersel: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Conceptualization. Bas J. Swarte: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Tineke E. Buffart: Writing – review & editing. Hans J. Pruijt: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Investigation, Conceptualization. Leonie J. Mekenkamp: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Miriam Koopman: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Anne M. May: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Sietske C.M.W. van Nassau: Received research funding via institution from Pierre Fabre, and support for attending meetings and/or travel via institution from Servier.

Helene R. Voogdt-Pruis: No competing interests to declare

Vincent M.W. de Jong: No competing interests to declare

Hans-Martin Otten: No competing interests to declare

Tineke E. Buffart: Reports having received payment for lectures for nurse practitioners via institution. Participates in the data safety monitoring board of a clinical trial.

Liselot B. Valkenburg-van Iersel: Received personal consulting fees from Amgen, Servier and Pierre Fabre, and personal support for attending meetings and/or travel from Servier.

Bas J. Swarte: No competing interests to declare

Hans J. Pruijt: Reports a leadership or fiduciary role in the quality commission of the Dutch society of Oncology (NVMO).

Leonie J. Mekenkamp: No competing interests to declare

Anne M. May: No competing interests to declare

Miriam Koopman: Reports having an advisory role for Eisai, Nordic Farma, Merck-Serono, Pierre Fabre, Servier (payments via institution). Institutional scientific grants from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Personal Genome Diagnostics (PGDx), Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanofi, and Servier. PI from the international cohort study PROMETCO with Servier as sponsor. Non-financial interests: chair of the ESMO RWD-DH working group, co- chair DCCG, PI PLCRC (national observational cohort study), involved in several clinical trials as PI or co-investigator in CRC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all participants for their participation in this study and ZorgKeuzeLab for their commitment to develop high quality decision aids with and for patients and health care providers. The authors would like to thank the Dutch Digestive Foundation (MLDS) and the Dutch patient federation for colorectal cancer (Stichting Darmkanker) for their support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2024.100300.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

Data availability

All transcripts and codes are archived by the first author (SN).

References

- 1.Biller L.H., Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:669–685. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shay L.A., Lafata J.E. Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:114–131. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14551638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stiggelbout A.M., Pieterse A.H., De Haes J.C.J.M. Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1172–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stacey D., Samant R., Bennett C. Decision making in oncology: a review of patient decision aids to support patient participation. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:293–304. doi: 10.3322/CA.2008.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stacey D., Légaré F., Lewis K., Barry M.J., Bennett C.L., Eden K.B., et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlpine K., Lewis K.B., Trevena L.J., Stacey D. What is the effectiveness of patient decision aids for cancer-related decisions? A systematic review subanalysis. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018:1–13. doi: 10.1200/CCI.17.00148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Weijden T., van der Kraan J., Brand P.L.P., van Veenendaal H., Drenthen T., Schoon Y., et al. Shared decision-making in the Netherlands: progress is made, but not for all. Time to become inclusive to patients. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2022;171:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2022.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noteboom E.A., May A.M., van der Wall E., de Wit N.J., Helsper C.W. Patients’ preferred and perceived level of involvement in decision making for cancer treatment: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2021;30:1663–1679. doi: 10.1002/pon.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuijpers M.M.T., Veenendaal H., Engelen V., Visserman E., Noteboom E.A., Stiggelbout A.M., et al. Shared decision making in cancer treatment: a Dutch national survey on patients’ preferences and perceptions. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022;31 doi: 10.1111/ecc.13534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elwyn G., Durand M.A., Song J., Aarts J., Barr P.J., Berger Z., et al. Van der Weijden, a three-talk model for shared decision making: multistage consultation process. BMJ. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keikes L., de Vos-Geelen J., de Groot J.W.B., Punt C.J.A., Simkens L.H.J., Trajkovic-Vidakovic M., et al. Implementation, participation and satisfaction rates of a web-based decision support tool for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elwyn G., Légaré F., van der Weijden T., Edwards A., May C. Arduous implementation: does the normalisation process model explain why it’s so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice. Implement Sci. 2008;3:57. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elwyn G., Scholl I., Tietbohl C., Mann M., Edwards A.G., Clay C., et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:S14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Donnell S., Cranney A., Jacobsen M.J., Graham I.D., O’Connor A.M., Tugwell P. Understanding and overcoming the barriers of implementing patient decision aids in clinical practice*. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12:174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph-Williams N., Abhyankar P., Boland L., Bravo P., Brenner A.T., Brodney S., et al. What works in implementing patient decision aids in routine clinical settings? A rapid realist review and update from the international patient decision aid standards collaboration. Med Decis Making. 2021;41:907–937. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20978208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stacey D., Suwalska V., Boland L., Lewis K.B., Presseau J., Thomson R. Are patient decision aids used in clinical practice after rigorous evaluation? A survey of trial authors. Med Decis Making. 2019;39:805–815. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19868193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Weijden T., Boivin A., Burgers J., Schünemann H.J., Elwyn G. Clinical practice guidelines and patient decision aids. An inevitable relationship. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanis P.J., Beets G.L., Beets-Tan R.G.H. 2021. Dutch national colorectal cancer treatment guideline.https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/colorectaal_carcinoom_crc/gemetastaseerd_colorectaalcarcinoom_crc/systemische_therapie_bij_niet_lokaal_behandelbare_metastasen_bij_crc.html (accessed June 14, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coulter A., Stilwell D., Kryworuchko J., Mullen P.D., Ng C.J., van der Weijden T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:S2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph-Williams N., Newcombe R., Politi M., Durand M.-A., Sivell S., Stacey D., et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:699–710. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13501721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonner C., Trevena L.J., Gaissmaier W., Han P.K.J., Okan Y., Ozanne E., et al. Current best practice for presenting probabilities in patient decision aids: fundamental principles. Med Decis Making. 2021;41:821–833. doi: 10.1177/0272989X21996328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleuren M.A.H., Paulussen T.G.W.M., Van Dommelen P., Van Buuren S. Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. International J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:501–510. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klaassen L.A., Friesen-Storms J.H.H.M., Bours G.J.J.W., Dirksen C.D., Boersma L.J., Hoving C. Perceived facilitating and limiting factors for healthcare professionals to adopting a patient decision aid for breast cancer aftercare: a cross-sectional study. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mol L., Koopman M., van Gils C.W.M., Ottevanger P.B., Punt C.J.A. Comparison of treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients included in a clinical trial versus daily practice in the Netherlands. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2013;52:950–955. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.777158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamers P.A.H., Elferink M.A.G., Stellato R.K., Punt C.J.A., May A.M., Koopman M., et al. Informing metastatic colorectal cancer patients by quantifying multiple scenarios for survival time based on real-life data. Int J Cancer. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Templeton A.J., Booth C.M., Tannock I.F. Informing patients about expected outcomes: the efficacy-effectiveness gap. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1651–1654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derksen J.W.G., Vink G.R., Elferink M.A.G., Roodhart J.M.L., Verkooijen H.M., van Grevenstein W.M.U., et al. The Prospective Dutch Colorectal Cancer (PLCRC) cohort: real-world data facilitating research and clinical care. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3923. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79890-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waddell A., Lennox A., Spassova G., Bragge P. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in hospitals from policy to practice: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16:74. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01142-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keikes L., Koopman M., Stuiver M.M., Lemmens V.E.P.P., van Oijen M.G.H., Punt C.J.A. Practice variation on hospital level in the systemic treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in the Netherlands: a population-based study. Acta Oncol (Madr) 2020;59:395–403. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1722320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Nassau S.C., Bond M.J., Scheerman I., van Breeschoten J., Kessels R., Iersel L.B. Valkenburg-van, et al. Trends in use and perceptions about triplet chemotherapy plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24766. e2124766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Tol-Geerdink J.J., van Oort I.M., Somford D.M., Wijburg C.J., Geboers A., van Uden-Kraan C.F., et al. Implementation of a decision aid for localized prostate cancer in routine care: a successful implementation strategy. Health Informatics J. 2020;26:1194–1207. doi: 10.1177/1460458219873528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuypers M., Lamers R.E., Kil P.J., van Tol-Geerdink J.J., van Uden-Kraan C.F., van de Poll-Franse L.V., et al. Uptake and usage of an online prostate cancer treatment decision aid in Dutch clinical practice: a quantitative analysis from the prostate cancer patient centered care trial. Health Informatics J. 2019;25:1498–1510. doi: 10.1177/1460458218779110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savelberg W., Boersma L.J., Smidt M., Weijden T. Implementing a breast cancer patient decision aid: process evaluation using medical files and the patients’ perspective. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021;30 doi: 10.1111/ecc.13387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kehl K.L., Landrum M.B., Arora N.K., Ganz P.A., Van Ryn M., Mack J.W., et al. Association of actual and preferred decision roles with patient-reported quality of care: shared decision making in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:50–58. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henselmans I., Van Laarhoven H.W., Van der Vloodt J., De Haes H.C., Smets E.M. Shared decision making about palliative chemotherapy: a qualitative observation of talk about patients’ preferences. Palliat Med. 2017;31:625–633. doi: 10.1177/0269216316676010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wasp G.T., Knutzen K.E., Murray G.F., Brody-Bizar O.C., Liu M.A., Pollak K.I., et al. Systemic therapy decision making in advanced cancer: a qualitative analysis of patient-oncologist encounters. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e1357–e1366. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scherr K.A., Fagerlin A., Hofer T., Scherer L.D., Holmes-Rovner M., Williamson L.D., et al. Physician recommendations trump patient preferences in prostate cancer treatment decisions. Med Decis Making. 2017;37:56–69. doi: 10.1177/0272989X16662841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herrmann A., Sanson-Fisher R., Hall A. Not having adequate time to make a treatment decision can impact on cancer patients’ care experience: results of a cross-sectional study. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:1957–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bomhof-Roordink H., Fischer M.J., van Duijn-Bakker N., Baas-Thijssen M.C., van der Weijden T., Stiggelbout A.M., et al. Shared decision making in oncology: a model based on patients’, health care professionals’, and researchers’ views. Psychooncology. 2019;28:139–146. doi: 10.1002/pon.4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribi K., Kalbermatten N., Eicher M., Strasser F. Towards a novel approach guiding the decision-making process for anticancer treatment in patients with advanced cancer: framework for systemic anticancer treatment with palliative intent. ESMO Open. 2022;7 doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

All transcripts and codes are archived by the first author (SN).