Abstract

For older persons with delirium at the end of life, treatment involves complex tradeoffs and highly value-sensitive decisions. The principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice establish important parameters but lack the structure necessary to guide clinicians in the optimal management of these patients. We propose a set of ethical rules to guide therapeutics—the canons of therapy—as a toolset to help clinicians deliberate about the competing concerns involved in the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life. These canons are standards of judgment that reflect how many experienced clinicians already intuitively practice, but which are helpful to articulate and apply as basic building blocks for a relatively neglected but emerging ethics of therapy. The canons of therapy most pertinent to the care of patients with delirium at the end of life are: 1) restoration, which counsels that the goal of all treatment is to restore the patient, as much as possible, to homeostatic equilibrium; 2) means-end proportionality, which holds that every treatment should be well-fitted to the intended goal or end; 3) discretion, which counsels that an awareness of the limits of medical knowledge and practice should guide all treatment decisions; and 4) parsimony, which maintains that only as much therapeutic force as is necessary should be used to achieve the therapeutic goal. Carefully weighed and applied, these canons of therapy may provide the ethical structure needed to help clinicians optimally navigate complex cases.

When older adults develop delirium at the end of life, overall management considerations are complex for both medical and ethical reasons. In the setting of advanced illness, delirium is often a preterminal event that results from potentially reversible causes, including infections, electrolyte disturbances, organ failure, and medication side effects.1–3 For individual patients, it may be unclear what their goals are and how aggressively they would want to pursue a diagnostic workup.1,2 Delirium interferes with the assessment and treatment of symptoms and causes significant distress; patients often recall their delirium, prolonging their distress.1,4 Clinicians therefore generally seek to prevent or reverse delirium. But if delirium in a patient with terminal illness is determined to result from disease progression—rather than reversible causes—the goals of care may shift to a focus on comfort.1

A significant barrier to determining the appropriate use of psychotropic medications for patients at the end of life is the lack of robust evidence to inform treatment decisions,5,6 as well as uncertainty about the optimal approach for an individual patient. Whereas the 2023 AGS Beers Criteria recommend avoiding antipsychotics for behavioral problems of delirium in older adults, these criteria “do not apply to care in hospice and at the end of life, in which setting decision-making…may require other considerations.”7 For patients with advanced illness, the use of antipsychotics to treat the symptoms of delirium—including agitation and restlessness—has been a mainstay for over two decades.8

Recent literature has considered the effects of antipsychotics on the syndrome of delirium itself: a pair of systematic reviews do not support their use for hospitalized older adults,9,10 and a Cochrane review found no high-quality evidence for or against pharmacologic treatments for delirium in terminally ill adults.11 Although the use of antipsychotics to treat delirium itself remains controversial,6,7,12 their use to treat the symptoms of delirium and promote comfort at the end of life is less controversial and deserves further study.6,13

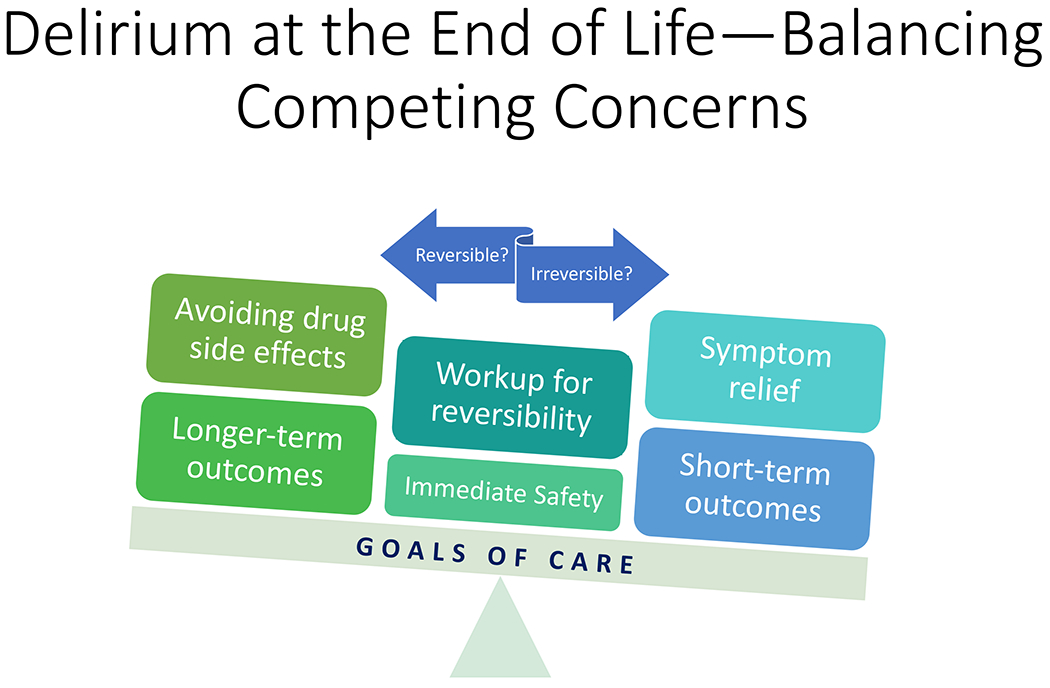

Figure 1 provides a schematic of competing concerns in the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life. Whereas ensuring immediate safety and assessing for reversible causes are important considerations in all cases, other concerns may receive different emphasis depending on the patient’s proximity to death, the patient’s goals of care, and the potential reversibility of the delirium. Clinicians need to balance the goals of avoiding drug side effects and prioritizing longer-term outcomes against the patient’s need for symptom relief and short-term outcomes.

Figure 1.

Competing concerns in the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life prompt the need for ethical approaches to aid clinicians as they navigate treatment decisions. Ensuring immediate safety and assessing for reversible causes are important considerations in all cases. Clinicians need to balance other concerns depending on the the patient’s goals of care and the potential reversibility of the delirium: avoiding drug side effects and prioritizing longer-term outcomes often compete against symptom relief and short-term outcomes.

Given the inherent complexity and uncertainty in navigating competing concerns for patients with delirium at the end of life, ethical approaches are needed to help clinicians in this process. The principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice provide important general parameters but lack the structure necessary to guide clinicians in the management of complex cases.14 Beauchamp and Childress emphasize the need to tailor the principles to particular cases through specifying and balancing—narrowing the scope of the principles and weighing them against each other.15 Yet these ethicists offer little guidance about how to do this, except to assert that persons of moral character have a greater aptitude for specifying and balancing principles.

As a practical complement to a principles-based approach, we propose a set of more specific rules that govern therapeutics—the canons of therapy—as a toolset to help clinicians deliberate more effectively about the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life.16 Previously described by Sulmasy and Jansen for their applicability in the end-of-life context, these canons are fundamental standards of judgment to guide best therapeutic practice; they serve as basic building blocks for a relatively neglected but emerging ethics of therapy.16,17

The canons have overlapping roles and collectively apply in every therapeutic case, regardless of the patient population or setting. Depending on the context, one or more canons may have particular salience. Many experienced clinicians already apply canons of therapy intuitively without recognizing them as such; nonetheless, it is helpful to articulate and apply the canons in complex and uncertain cases to determine more effectively the “right and good” healing act for this patient.18,19 We propose that the canons are especially helpful in clinical scenarios involving complex tradeoffs and highly value-sensitive decisions. Although in this article we will focus on cases involving delirium in older adults at the end of life, the canons may prove equally valuable in navigating other cases, such as those involving older patients with cognitive impairment20 or multiple morbidities.21

Ultimately, the canons of therapy are medical specifications of an important virtue that is at once intellectual and ethical—the virtue of phronesis or practical wisdom.19 As ethical heuristics aligned with practical wisdom, the canons are more helpful in guiding complex therapeutic judgments than the four principles. The novelty of this paper is framing the approach to delirium in terms of ethics and not merely evidence-based practice, and showing how the canons of therapy apply in this particular clinical context.

The canons of therapy most pertinent to the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life—which we consider in turn, each with a case illustration intended to highlight a single canon—are restoration, means-end proportionality, discretion, and parsimony (See Table 1 for descriptions and clinical examples).16

Table 1.

The canons of therapy as a set of specific rules to guide clinicians’ approaches to treatment, and their application in example cases involving delirium.

| Canon | Description | Clinical example |

|---|---|---|

| Restoration | The goal of all treatment is to restore the patient, as much as possible, to homeostatic equilibrium; restoration can be complete, as with cure, or partial, as with relief of symptoms. | In the case of Mrs. R, a 68-year-old woman with colorectal cancer metastatic to the lung, treatment of her pulmonary embolism and her symptoms related to delirium aimed at partial restoration so that she could enjoy visits from family members and a chaplain. |

| Means-end proportionality | Every treatment should be well-fitted to the intended goal or end; in contrast, end-end proportionality involves weighing the expected benefits and burdens of a treatment. | For Mr. M, a 62-year-old man with liver cirrhosis, treatment of his hepatic encephalopathy without use of antipsychotics aimed at improving his mental status without abruptly stopping his “pleasant” hallucinations that may have had existential or religious meaning. |

| Discretion | An awareness of the limits of medicine—those of the craft itself, its evidence base, and clinicians’ own expertise—should guide all treatment decisions. | In the case of Mr. D, a 77-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease-related dementia, available evidence did not support the use of clinically assisted hydration to prevent delirium; however, given his pattern of failure to thrive leading to delirium, Mr. D opted for feeding tube placement and its use at home. |

| Parsimony | Only as much therapeutic force as is necessary should be used to achieve the therapeutic goal; this is justified primarily by concern for the patient’s well-being—“do no harm.” | For Ms. P, a 74-year-old woman with breast cancer metastatic to bone and liver, she wanted “to take the edge off” her symptoms but to remain alert and interactive; she was prescribed modest doses of medications for pain and anxiety, with due consideration of her reduced kidney and liver function. |

Restoration

Mrs. R is a 68-year-old woman with colorectal cancer metastatic to the lung. She is admitted to the hospital with failure to thrive and altered mental status. She is also noted to be very anxious. On the medical ward she develops acute respiratory distress and is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). An imaging study shows disease progression, and in the setting of declining functional status, it is determined that she is not a candidate for additional cancer-directed therapies.

Overnight, Mrs. R reports feeling suffocated and trapped in her room. She states that she has not spent enough time with her family and wants to leave the ICU. She is given small doses of benzodiazepine without relief, and her mental status worsens. The ICU team requests a psychiatry consultation for evaluation of her anxiety and organizes a meeting with her family to discuss goals of care.

The canon of restoration counsels that the goal of all treatment is to restore the patient, as much as possible, to homeostatic equilibrium.16–18 Although cure or complete restoration may not be an option for patients such as Mrs. R, it is still possible to work toward partial restoration—whether that involves management of illness, alleviation of suffering, or promotion of psychosocial or spiritual well-being.16–18 Further, the canon of restoration requires that clinicians aim for restoration as the overall goal, not simply a short-term one. In some cases, for instance, conservative management does not restore a patient immediately, although it may achieve the best eventual result.

For this patient, the search for at least partial restoration led to a combination of interventions from the ICU and psychiatry teams that they would not have otherwise pursued. They might merely have sedated her without attempting to improve her symptoms, even if transiently. The ICU team considered whether another disease process besides metastatic cancer was contributing to Mrs. R’s respiratory distress. They agreed that, despite her limited prognosis, it may be possible to restore her breathing enough to leave the ICU. Further medical workup yielded a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. With the initiation of anti-coagulation, her breathing and anxiety improved. She also received several doses of haloperidol for symptomatic treatment of her delirium.

After transfer to the medical ward, Mrs. R enjoyed frequent visits from family members and requested a Catholic chaplain. Although her delirium improved, within a few days it became clear that the main cause was disease progression rather than reversible causes. Opportunities for restoration had narrowed. In a family meeting, she changed her status to comfort measures only and consented to a Do-Not-Resuscitate order.

Means-end proportionality

Mr. M is a 62-year-old man with liver cirrhosis secondary to untreated hepatitis C. He and his family recently immigrated to the United States from Vietnam. He is admitted to the hospital with hepatic encephalopathy after presenting to clinic, where he was noted to be quieter than usual, muttering to himself, and slowly reaching for unseen objects.

On evaluation by the medical team, Mr. M is minimally interactive but verbalizes images of his dead relatives opening the gates of heaven to him. The psychiatry team is consulted and recommends low-dose haloperidol for hallucinations. His wife at the bedside adamantly declines medications for the “pleasant images” he is experiencing. She adds, “This is the first time he has smiled in weeks—please do not take it away from him!”

The canon of means-end proportionality advises that the treatment should be well-fitted to the intended goal or end.16 In medical ethics, proportionality is typically understood to involve a weighing of the expected benefits and burdens of a treatment, or the end-end proportionality; however, as this case illustrates, consideration of the means-end proportionality may be decisive.17 Attention to means-end proportionality led the team to apply standard treatments for Mr. M’s hepatic encephalopathy, including lactulose—the best means for achieving the goal of abating his delirium. These treatments aimed at improving his delirium without abruptly stopping his “pleasant” hallucinations.22 By contrast, a consideration of end-end proportionality alone might have led the team to use haloperidol, since this drug is generally effective and well-tolerated for the treatment of hallucinations. Yet that would not be the best means, and the end would likely have been sedation rather than alertness with improved delirium.

In this case, Mr. M’s wife prompted the team’s application of means-end proportionality by raising concerns about the goals of the proposed treatment: if the team gives haloperidol, will this work towards a desired end? The patient’s hallucinations did not seem to cause him suffering or distress, and they may have been meaningful to him on existential and religious levels. This is notable because hallucinations in the setting of delirium are often distressing to patients, who may later recall them.4,23

It is necessary to clarify a few related clinical points. This patient exhibited common features of the hypoactive subtype of delirium, including psychomotor retardation, lethargy, and reduced awareness of surroundings.8 Hallucinations were previously thought rare for patients with hypoactive delirium, but a recent study identified them in 51% of cases.24 Since patients with hypoactive delirium sometimes present with subtle signs of altered mental status and reduced psychomotor activity, they may go either undiagnosed or misdiagnosed with fatigue or depression.25 Finally, it is helpful to note that hypoactive delirium can develop into hyperactive delirium at any time, and hallucinations can turn from pleasant to distressing ones—in which case low-dose haloperidol could be considered.4

Discretion

Mr. D is a 77-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease-related dementia. He lives at home with his wife. Over the past three months, he has had three hospital admissions for delirium—each time with a pattern of failure to thrive and dehydration that improved markedly with intravenous hydration, followed by eventual discharge to home. He is admitted to the hospital again for the same reason.

Weary of this pattern, Mr. D’s wife requests intravenous hydration at home to prevent him from becoming confused. Although Mr. D had told her previously that he did not want aggressive measures, she cannot bear to see him like this. As she points out, he seems to do well with hydration: “He always perks up and smiles when the fluids are running.” The medical team is inclined to deny her request, but places an ethics consult to consider provision of atypical resources for this patient.

The canon of discretion involves an awareness of the limits of medicine—those of the craft itself, its evidence base, and clinicians’ own expertise—to guide treatment decisions.16 Given these limits, the use of discretion generally entails navigating clinical uncertainty.26 For Mr. D, his wife’s request touches on a few areas of uncertainty: whether intravenous fluids at home would prevent future episodes of delirium, whether Mr. D would have wanted it, and whether it is feasible.

Regarding the question of intravenous fluids, a pair of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to conclude on the impact of clinically assisted hydration for patients in the end-of-life context.27,28 The studies included in these reviews involved either intravenous or subcutaneous administration of fluids; no study involved the enteral route. Currently, one large randomized controlled trial is underway to determine whether intravenous or subcutaneous fluids in the last week of life prevents delirium.29

Mindful of the limited scientific evidence, as well as Mr. D’s pattern of delirium in the setting of failure to thrive and improvement with intravenous hydration, it seems reasonable to consider provision of clinically assisted hydration at home with the goal of preventing delirium. In contrast, failure to consider this management option for Mr. D would violate the canon of discretion, since insistence on evidence when the data are lacking would have overestimated the power of medicine when a humble recognition of the limits of medical knowledge would permit a trial-and-error approach. As for Mr. D’s preferences and the feasibility of clinically assisted hydration at home, these questions warrant further discussion involving the team and Mr. D’s wife.

Following a family meeting, Mr. D’s wife agreed to discuss this matter further with Mr. D once his delirium improved. She also received education regarding the challenges of detecting and treating delirium in persons with dementia, in anticipation that he may have future episodes at home.30,31 Several days later, Mr. D could engage in conversation and agreed to the placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube to facilitate feeding and hydration at home.32 He tolerated the procedure well and had no further hospitalizations for delirium following discharge.

Parsimony

Ms. P is a 74-year-old woman with breast cancer metastatic to bone and liver. As part of her enrollment in home hospice, she needs an initial evaluation and medication review at her home. She reports a pain level of 7/10 related to her bone metastases and moderate nausea. When asked about her treatment goals, she states that she wants “to take the edge off” her symptoms, but also prefers to remain alert and interactive for visits from her two sisters and her friends from church.

A medication review reveals that she has been prescribed, for many years, diazepam for anxiety and naproxen for chronic back pain. Her recent medical history and labs are notable for moderate renal insufficiency and slightly elevated liver enzymes.

The canon of parsimony counsels that one use only as much therapeutic force as is necessary to achieve the therapeutic goal.16,18 Parsimony is justified primarily by concern for the patient’s well-being: overtreatment can be harmful.16,33 For patients receiving palliative or hospice care, several classes of commonly used medications may contribute to delirium—including opiates, corticosteroids, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics.3,34 Moreover, as the list of medications grows, the risk for drug-drug interactions and adverse drug events increases.35

A parsimonious approach to prescribing for Ms. P would involve using the fewest drugs in the smallest doses needed to treat her symptoms, mindful of the potential for various therapeutic harms. Ms. P’s stated preference to maintain alertness rather than pursue aggressive symptom management calls for even greater attentiveness to the canon of parsimony.

Notably, the role that such an approach might have in preventing delirium for Ms. P remains unknown—delirium prevention in patients with cancer has not yet been demonstrated.5,36 Two controlled trials have attempted this by means of a multicomponent intervention: one did not reduce delirium incidence,37 and the other did not advance beyond Phase II due to low adherence.38 Nonetheless, for older hospitalized adults, early identification of risk factors for delirium has been shown to reduce the incidence of delirium.39

Given her renal insufficiency, Ms. P was started on low-dose hydromorphone rather than morphine, her naproxen was discontinued, her diazepam was replaced with lorazepam, and she was started on low-dose haloperidol rather than olanzapine for nausea. She tolerated these medication changes well and had no complaints on follow-up evaluation.

Applying the Canons Together—The Case of Mr. C

In light of the canons of therapy discussed above—restoration, means-end proportionality, discretion, and parsimony—it is now possible to apply them together in a structured ethical approach for a patient with delirium in the setting of advanced illness.

Mr. C is a 65-year-old man with metastatic prostate cancer. He has been on home hospice care but is now admitted to the hospital with altered mental status. The medical team overseeing his care is uncertain whether his delirium is primarily due to disease progression or a reversible cause. His low dose of oxycodone for pain was recently increased due to worsening pain from bone metastases. He also takes hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension and diphenhydramine for difficulty sleeping.

An initial diagnostic workup reveals hypercalcemia and new bone lesions. He is given intravenous fluids, low-dose morphine for pain, and low-dose haloperidol for agitation—to prevent severe agitation and keep him from causing harm to himself and others. Several hours later, his mental status worsens, including bouts of severe agitation. His family believes his worsened status is medication-related, and they insist on stopping all intravenous drugs. The medical team requests an ethics consult and organizes an interdisciplinary meeting with his family to discuss the plan of care.

Mr. C’s family has expressed concerns about therapeutic harm as his mental status worsens. Given the limited evidence to argue for or against the use of antipsychotics to treat delirium, the canon of discretion would suggest acknowledging this uncertainty to the family and clarifying why the use of certain medications might still be important. Simply continuing haloperidol without such a discussion not only opposes discretion but also risks violating the family’s trust.

Means-end proportionality offers clarity regarding the initial approach to treatment. It remains unclear whether Mr. C’s delirium is due primarily to disease progression or reversible causes, and therefore unclear what means of treatment would be most appropriate.1 Nonetheless, antipsychotics may be the best short-term measure to keep him safe during bouts of severe agitation.6 Without knowing how aggressively Mr. C would want to pursue a diagnostic workup, the team could continue to treat his pain—which, if left untreated, may worsen delirium—and could consider additional ways of addressing contributors to his delirium. The overall goal is to work towards resolving his delirium by means of targeted nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches, unless it becomes clear that his delirium is irreversible.1 Inattentiveness to the possible reversible causes of delirium may limit the chances of attaining this goal.

Restoration for Mr. C can be viewed with respect to short-term and overall goals. Whereas the management of his severe anxiety and pain is restorative in the short-term, the resolution of his delirium by addressing its potential causes is restorative in a broader and more enduring sense. For instance, if a combination of intravenous hydration and bisphosphonate are effective in managing his hypercalcemia—which may be an important contributor to his delirium—then further steps could be taken to keep his calcium level within a reasonable range and potentially prevent delirium recurrence. Failure to treat his hypercalcemia and other possible reversible causes of his delirium would violate the canon of restoration and potentially foreclose prematurely efforts to reverse his delirium.

A parsimonious approach to prescribing in this case requires a difficult balance because of the need both to address his symptoms and to manage his delirium. More straightforwardly, two of Mr. C’s home medications are possible contributors to his delirium and should be discontinued: hydrochlorothiazide, for its dehydrating effects and tendency to raise calcium levels; and diphenhydramine, for its anticholinergic properties. According to the canon of parsimony, less is often more.33 Regarding Mr. C’s pain and anxiety, he may be tolerating the morphine and haloperidol, but it is worth considering a trial of alternatives like hydromorphone and risperidone.40 Most importantly, the canon of parsimony requires a careful review of his medications to ensure a thoughtful and balanced approach.

Given the uncertainties involved in navigating Mr. C’s case, perhaps discretion is the most important canon that brings the others together. Not only is the scientific evidence unclear regarding the optimal management of delirium for patients at the end of life, but it remains unclear whether the delirium Mr. C is experiencing is preterminal or chiefly due to disease progression. Discretion is needed to thoughtfully consider the circumstances and treatment options, mindful of the limits of medicine and the requests of the family on behalf of Mr. C. Over the course of a few days, it may become clearer whether his delirium is reversible, and whether the goals should shift to focus on comfort.1 The canon of discretion counsels that when diligent efforts to reverse delirium have failed, one should recognize the limits of medicine and adjust one’s goals.

Taken together, these canons of therapy may help guide clinicians to navigate medically and ethically complex cases with the virtue of phronesis or practical wisdom. For patients with delirium at the end of life, applying an ethical lens can help optimize their care in the face of uncertainty.

Key points:

Overall management considerations for older patients with delirium at the end of life are complex for both medical and ethical reasons.

We propose a set of ethical rules to guide therapeutics—the canons of therapy—as a toolset to help clinicians deliberate about the management of complex cases.

These canons of therapy, which include restoration, means-end proportionality, discretion, and parsimony, reflect how many experienced clinicians intuitively practice but nonetheless may prove valuable as basic building blocks to guide ethical treatment decisions at the end of life.

Why does this paper matter?

The canons of therapy, carefully weighed and applied, may provide the ethical structure needed to help clinicians navigate the inherit complexity and uncertainty surrounding the management of older patients with delirium at the end of life.

Financial support:

Drs. Thomas and Sulmasy are supported by a grant from the McDonald Agape Foundation. The funding source had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitbart W, Alici Y. Agitation and delirium at the end of life: “We couldn’t manage him.” JAMA. 2008:2898–910, E1. vol. 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bramati P, Bruera E. Delirium in Palliative Care. Cancers (Basel). Nov 23 2021;13(23)doi: 10.3390/cancers13235893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al. Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2000:786–94. vol. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics. May-Jun 2002;43(3):183–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawlor PG, Rutkowski NA, MacDonald AR, et al. A Scoping Review to Map Empirical Evidence Regarding Key Domains and Questions in the Clinical Pathway of Delirium in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. Mar 2019;57(3):661–681.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meagher D, Agar MR, Teodorczuk A. Debate article: Antipsychotic medications are clinically useful for the treatment of delirium. Review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Nov 2018;33(11):1420–1427. doi: 10.1002/gps.4759. Epub 2017 Jul 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jul 2023;71(7):2052–2081. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart W, Alici Y. Evidence-based treatment of delirium in patients with cancer. Review. J Clin Oncol. Apr 10 2012;30(11):1206–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8784. Epub 2012 Mar 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, et al. Antipsychotics for Treating Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review. Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. Oct 1 2019;171(7):485–495. doi: 10.7326/M19-1860. Epub 2019 Sep 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic Medication for Prevention and Treatment of Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. Apr 2016;64(4):705–14. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14076. Epub 2016 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finucane AM, Jones L, Leurent B, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 21 2020;1(1):CD004770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004770.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. Review. JAMA. Sep 26 2017;318(12):1161–1174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grouls A, Bruera E, Hui D. Do Neuroleptics Still Have a Role in Patients With Delirium? Ann Intern Med. 2020:295. vol. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clouser KD, Gert B. A critique of principlism. J Med Philos. Apr 1990;15(2):219–36. doi: 10.1093/jmp/15.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Eighth edition. Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulmasy DP. The last low whispers of our dead: when is it ethically justifiable to render a patient unconscious until death? Theor Med Bioeth. Jun 2018;39(3):233–263. doi: 10.1007/s11017-018-9459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jansen LA, Sulmasy DP. Proportionality, terminal suffering and the restorative goals of medicine. Theor Med Bioeth. 2002;23(4–5):321–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1021209706566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pellegrino ED, Thomasma DC. A Philosophical Basis of Medical Practice: Toward a Philosophy and Ethic of the Healing Professions. Oxford University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis FD. Phronesis, clinical reasoning, and Pellegrino’s philosophy of medicine. Theor Med. Mar-Jun 1997;18(1–2):173–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotanda H, Walling AM, Reuben DB, Lauzon M, Tsugawa Y. Trends in advance care planning and end-of-life care among persons living with dementia requiring surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. May 2022;70(5):1394–1404. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. Oct 2008;56(10):1839–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al Sibae MR, McGuire BM. Current trends in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. Jun 2009;5(3):617–26. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s4443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. May 1 2009;115(9):2004–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boettger S, Breitbart W. Phenomenology of the subtypes of delirium: phenomenological differences between hyperactive and hypoactive delirium. Palliat Support Care. Jun 2011;9(2):129–35. doi: 10.1017/s1478951510000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawlor PG, Bruera ED. Delirium in patients with advanced cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. Jun 2002;16(3):701–14. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mort EA, Weissman JS, Epstein AM. Physician discretion and racial variation in the use of surgical procedures. Arch Intern Med. Apr 11 1994;154(7):761–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Good P, Richard R, Syrmis W, Jenkins-Marsh S, Stephens J. Medically assisted hydration for adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Apr 23 2014;2014(4):Cd006273. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006273.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kingdon A, Spathis A, Brodrick R, Clarke G, Kuhn I, Barclay S. What is the impact of clinically assisted hydration in the last days of life? A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Mar 2021;11(1):68–74. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies A, Barry C, Barclay S. What is the role of clinically assisted hydration in the last days of life? Bmj. Mar 17 2023;380:e072116. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fick DM. Knowing the Older Adult With Delirium Superimposed on Dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Oct 2022;30(10):1079–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morandi A, Lucchi E, Turco R, et al. Delirium superimposed on dementia: A quantitative and qualitative evaluation of informal caregivers and health care staff experience. J Psychosom Res. Oct 2015;79(4):272–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown L, Oswal M, Samra AD, et al. Mortality and Institutionalization After Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in Parkinson’s Disease and Related Conditions. Mov Disord Clin Pract. Jul 2020;7(5):509–515. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grady D, Redberg RF. Less is more: how less health care can result in better health. Arch Intern Med. May 10 2010;170(9):749–50. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bush SH, Bruera E. The assessment and management of delirium in cancer patients. Oncologist. Oct 2009;14(10):1039–49. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNeil MJ, Kamal AH, Kutner JS, Ritchie CS, Abernethy AP. The Burden of Polypharmacy in Patients Near the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. Feb 2016;51(2):178–83.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Del Fabbro E, Dalal S, Bruera E. Symptom control in palliative care--Part III: dyspnea and delirium. J Palliat Med. Apr 2006;9(2):422–36. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagnon P, Allard P, Gagnon B, Mérette C, Tardif F. Delirium prevention in terminal cancer: assessment of a multicomponent intervention. Psychooncology. Feb 2012;21(2):187–94. doi: 10.1002/pon.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosie A, Phillips J, Lam L, et al. A Multicomponent Nonpharmacological Intervention to Prevent Delirium for Hospitalized People with Advanced Cancer: A Phase II Cluster Randomized Waitlist Controlled Trial (The PRESERVE Pilot Study). J Palliat Med. Oct 2020;23(10):1314–1322. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. Apr 2015;175(4):512–20. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boettger S, Jenewein J, Breitbart W. Haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine and aripiprazole in the management of delirium: A comparison of efficacy, safety, and side effects. Palliat Support Care. Aug 2015;13(4):1079–85. doi: 10.1017/s1478951514001059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]