Since the AIDS epidemic of the early 1980s the interest in alternatives to allogeneic transfusion has grown, particularly for elective surgery. One alternative that currently accounts for over 5% of the blood donated in the United States and some countries in Europe is autologous transfusion, obtained primarily by preoperative donation. Although autologous transfusion is used less widely in the United Kingdom than in the United States, guidelines on its use have recently been published in the United Kingdom.1 We describe the three main types of autologous transfusion and draw attention to the advantages and disadvantages of each technique (see table A on bmj.com). We also review the evidence from observational and controlled trials comparing autologous with allogeneic transfusion.

Summary points

Autologous transfusion reduces the need for allogeneic transfusion and is most widely used in elective surgery

Autologous transfusion is one of several techniques used to reduce the need for allogeneic transfusion

The three main techniques are predeposit transfusion, intraoperative haemodilution, and intraoperative and postoperative salvage

Evidence from clinical trials shows that autologous transfusion is more cost effective than allogeneic transfusion and that clinical outcomes are improved

Methods

We searched Index Medicus for publications on autologous transfusion. Many descriptive and methodological papers have described the efficacy of autologous transfusion in reducing allogeneic transfusion. Recent books and reviews address the technical and clinical aspects of the three types of autologous transfusion in detail.2–4 It is accepted that these techniques reduce the use of allogeneic blood, but the quality of the evidence varies, and possible drawbacks, such as temporary anaemia, have not yet been studied thoroughly.5,6

Autologous transfusion driven by concerns about the safety of blood

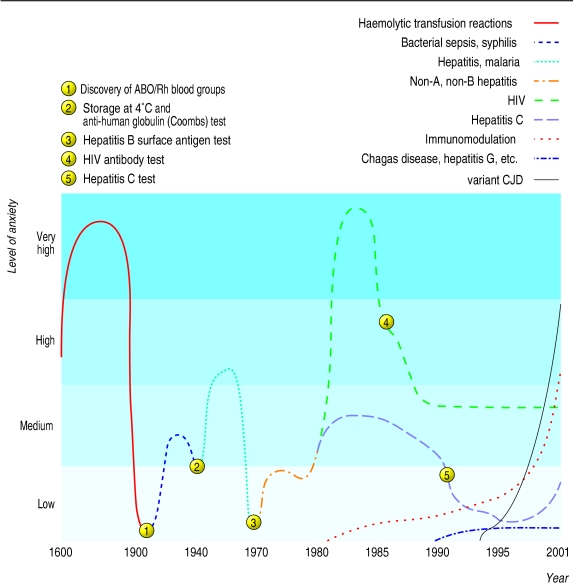

Transfusion is a ubiquitous and potent treatment underlying much of modern medical practice. Once an unquestioned adjunct to patient care, allogeneic transfusion is currently being re-evaluated, and alternatives to conventional practice are being considered in response to numerous concerns about the safety of the procedure (fig 1). These include decreased cell mass and occasional transient hypotension. The most recent stimulus for the use of autologous transfusion is evidence that allogeneic transfusion may lead to an increased risk of postoperative bacterial infections and multiorgan failure.7 Another potential stimulus is increased demand for blood with a declining population of qualified, willing, and healthy donors. Three main techniques for autologous transfusion are used—predeposit transfusion, acute normovolaemic haemodilution, and interoperative and postoperative blood salvage.

Figure 1.

The degree of anxiety and concern about the safety of blood transfusion over the centuries

Predeposit autologous transfusion

Predeposit autologous transfusion entails repeated preoperative phlebotomy (fig 2). Blood collection begins three to five weeks before elective surgery, depending on the number of units required, usually 2-4 units (about 1-2 litres). The last donation takes place at least 48-72 hours before surgery to allow for re-equilibration of the blood volume. On each occasion, about half a litre of the patient's own blood is taken and put into sterile plastic bags. Anticoagulation is maintained with citrated glucose solution, and the blood is stored until the time of surgery.

Figure 2.

WILL AND DENI MCINTYRE/SPL

Blood collection before preoperative autologous transfusion begins several weeks before surgery, and phlebotomy may be carried out several times

Advantages

Predeposit autologous transfusion virtually eliminates the risks of viral transmission and immunologically mediated haemolytic, febrile, or allergic reactions. These adverse effects range in frequency from 1 in 1 000 000 (HIV) to as high as 5% (febrile reactions). In addition, it may decrease the risk of postoperative infection and recurrence of cancer because immunomodulation as a result of transfusion is avoided.2–4 Immunomodulation refers to decreases in cellular immune function that have been documented after allogeneic, but not autologous, transfusions.7

Disadvantages

Up to half of the blood that is collected may be discarded because the amount drawn off needs to exceed the median routinely needed to avoid additional allogeneic transfusions. Leftover blood can rarely be used for other patients because most autologous donors do not meet the stringent health requirements for allogeneic blood donation. This wastage of blood and the costs of administering autologous programmes result in collection costs that are higher than those for allogeneic transfusion. Volume overload, bacterial contamination, and ABO haemolytic reactions to the transfusion resulting from administrative or clerical errors are further risks.

Suitability of patients

Predeposit autologous donation is practical only for elective surgery. Patients must be willing and able to travel to a donation centre before their operation, which can be inconvenient and stressful and may decrease their productivity at work. Because preoperative donation results in perioperative anaemia (which may not be completely resolved before surgery) blood volume, venous access, packed cell volume, and haemodynamic stability are important determinants of who is an appropriate candidate for the procedure. Children who weigh less than 30-40 kg are usually not suitable, but adult patients are deferred from donation only if they have severe haemodynamic problems, active systemic infections, or a history of serious reactions to donation (such as seizure). Patients with diarrhoeal illnesses in the days or weeks before donation should not donate as they may be at increased risk of bacterial contamination of their donated blood. Although autologous donors have a higher incidence of reactions such as fainting or dizziness than voluntary donors (presumably because they are inexperienced donors and not as young and fit), their reactions are seldom severe.

Intraoperative acute normovolaemic haemodilution

Acute normovolaemic haemodilution (“haemodilution”) is a type of autologous donation that is performed preoperatively in the operating theatre or anaesthetic area. It is usually restricted to patients in whom substantial blood loss is predicted (>1 litre or 20% of blood volume). Whole blood (1.0-1.5 litres) is removed, and simultaneously intravascular volume is replaced with crystalloid or colloid, or both, to maintain blood volume. The anticoagulated blood is then reinfused in the operating theatre during or shortly after surgical blood loss has stopped. The blood sparing benefit of haemodilution is the result of the reduced red cell mass lost during surgical bleeding.

Advantages

Haemodilution provides the advantages of predeposit autologous donation and some additional benefits. It may be used before any type of surgical procedure, and systemic infection does not preclude its use. The patient is under anaesthesia during the procedure, which reduces stress, and the anaesthetist can ensure expert monitoring of blood circulation. Blood is stored at room temperature for a short time, so deterioration of clotting factors and cells is minimal. Additional advantages include a lower cost than for predeposit transfusion (because testing and cross matching are not usually required) and minimal wastage, as most or all blood is reinfused. Blood is maintained at the point of care, incurring little or no administrative expense, and the risk of ABO incompatibility because of administrative or clerical error is further minimised.

Disadvantages

The circulating red cell mass is lowered appreciably and acutely. If colloid is used for volume replacement the risk of allergic reactions or haemostatic abnormalities increases. Other disadvantages are the additional expense of, and inconvenience to, the anaesthetist who performs the procedure. The procedure may require additional training and experience on the anaesthetist's part. No large studies have investigated morbidity or mortality that may occur with acute anaemia, so the general belief that haemodilution is safe is largely anecdotal at this time.

Suitability of patients

Elective operations with typical blood losses of 1-2 litres are particularly suitable for haemodilution (for example, replacement of cardiac valves, revision of hip arthroplasty, or spinal reconstruction). The major limiting factor in choosing candidates for haemodilution is the patient's ability to tolerate a low volume of red blood cells. Patients with severe anaemia are usually poor candidates.

Salvage autologous transfusion

Intraoperative red blood cell salvage entails the collection and reinfusion of blood lost during surgery. Shed blood is aspirated from the operative field into a specially designed centrifuge. Citrate or heparin anticoagulant is added, and the contents are filtered to remove clots and debris. Centrifuging concentrates the salvaged red cells, and saline washing may be used. This concentrate is then reinfused. Devices used can vary from simple, inexpensive, sterile bottles filled with anticoagulant to expensive, sophisticated, high speed cell washing devices. Postoperative salvage refers to the process of recovering blood from wound drains and reinfusing the collected fluid with or without washing.

Advantages

Salvage is considered a safe and efficacious alternative to allogeneic red cell transfusion, but fewer data are available about clinical outcomes than for predeposit autologous donation or haemodilution.1 These techniques offer advantages similar to those of haemodilution but do not require infusions of crystalloid or colloid to preserve blood volume. Many litres of blood can be salvaged intraoperatively during extensive bleeding, far more than with other autologous techniques.

Disadvantages

Although the oxygen transport properties and survival of red cells are similar to that of allogeneic blood, salvaged blood is not haemostatically intact compared with blood derived by haemodilution. Coagulation in the wound leads to consumption of coagulation factors and platelets. Salvaged blood that is not washed contains raised concentrations of various tissue materials. Uncommon complications of extensive intraoperative salvage include disturbances to pH and electrolytes, systemic dissemination of non-sterile material, infectious agents or malignant cells, air or fluid embolism, and dilutional coagulopathy. A “salvaged blood syndrome” has been described, which entails multiorgan failure and consumption coagulopathy.8

Suitability of patients

Intraoperative salvage is used extensively in cardiac surgery, trauma surgery, and liver transplantation. Contraindications to its use are bacterial infection or malignant cells in the operative field, and use of microfibrillar collagen or other foreign material at the operative site. Salvage can be one of the most expensive autologous techniques because costly capital equipment and disposables are used, and it is usually restricted to procedures resulting in substantial blood loss (>1-2 litres).

Data on clinical outcomes

Observational studies

Many studies have examined whether patients who donate and receive autologous blood fare better clinically than those who receive allogeneic blood only (see table B on bmj.com). Of 16 studies, 10 found statistically significant reductions in unfavourable postoperative outcomes (primarily infections) in patients receiving autologous blood. Five found trends to improved outcomes that did not reach significance; one study found significantly better outcomes in patients receiving allogeneic transfusions.

Randomised trials

The number of randomised studies is small and the quality of the reporting variable. In four of the five studies to date, patients randomised to receive autologous rather than allogeneic transfusions had better clinical outcomes (table).9–14 Improved outcomes included a reduction in postoperative infections.10–13 One study found a trend to reductions in recurrence of colorectal cancer with autologous transfusions.14 One third of the patients randomised to receive autologous blood also received allogeneic transfusions because their blood loss was too high to be treated with the autologous blood alone. The data from randomised trials thus confirm the results of observational studies: postoperative complications of surgery may be reduced by using autologous transfusions. These results currently provide one of the strongest arguments for the use of autologous transfusions.

Additional educational resources

National Audit Office, National Blood Service, Department of Health (www.doh.gov.uk/bbt2/). This website contains the proceedings of the conference on better blood transfusion, hosted by the United Kingdom's chief medical officers in October 2001, and links to many related sites.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/54/section1.html). The introductory section of the recently prepared Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network on perioperative blood transfusion for elective surgery.

University of Pisa, Bloodless Medicine Research (www.med.unipi.it/patchir/bloodl/bmr.htm). This website contains current research on alternatives to allogeneic transfusion and links to other academic and clinical centres specialising in bloodless medicine and surgery.

Network for the Advancement of Transfusion Alternatives (www.nataonline.com). Nataonline is the home page of the network for the advancement of transfusion alternatives (NATA), a recently formed international academic and clinical society.

NoBlood. www.noblood.com. NoBlood is of particular interest to patients, organised by proponents of bloodless medicine and surgery, especially relevant to addressing the needs of Jehovah's Witnesses. Links to hospitals with programmes, primarily in the United States.

New Jersey Institute for the Advancement of Bloodless Medicine and Surgery (www.bloodlessmed.com). This is the home page of Englewood Hospital and Medical Center of New Jersey, which has a longstanding commitment to alternatives to allogeneic transfusion,.

Johns Hopkins University (www.atpcenter.org). This is the home page of the recently established Eugene and Mary B Meyer Center for Advanced Transfusion Practices and Blood Research in Baltimore, Maryland.

Cost effectiveness of autologous transfusion

Some studies take into account increases in the risks of postoperative infection mediated by immunomodulation with allogeneic but not autologous transfusions. These studies have found autologous transfusion to be cost effective and perhaps even cost saving.15,16 A study that did not address the possible immunomodulatory effects of transfusion found that autologous transfusion is not cost effective.17

In the United States issues of cost effectiveness were secondary to the desire of patients to minimise risks associated with transfusion through autologous donation during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. The demand for autologous transfusion has decreased as patients have become less concerned over the safety of transfusion, primarily because of improved testing for viral agents such as HIV and hepatitis.

Other concepts that spare blood transfusion

Erythropoietin, the red cell production hormone, can reduce the need for transfusion in stable medical patients with cancer and premature newborn infants. It can also be used to reduce the need for allogeneic transfusion in surgical patients, with or without concomitant autologous collection.18,19 Perioperative anaemia and blood loss can also be dealt with by reducing the amount of blood lost at surgery through improving mechanical haemostasis, using antifibrinolytics such as aprotinin, limiting phlebotomy to essential diagnostic tests, and using microsample laboratory techniques.20 Autologous transfusions also form part of a new concept of blood management called bloodless medicine and surgery.21 This includes the use of erythropoietin, surgical techniques that minimise blood loss, and drugs that inhibit fibrinolysis; greater degrees of anaemia are tolerated, and phlebotomy undertaken for diagnostic testing is minimal.20 Some of these methods are neither technically demanding nor expensive and may be adaptable to medical practice in less developed settings. The excellent results obtained in patients who are Jehovah's Witnesses, who refuse allogeneic transfusions, and the potential advantage of using fewer transfusions in patients in critical care support the promise of this concept for allogeneic transfusion.22

Supplementary Material

Table.

Clinical outcomes of randomised trials of autologous versus allogeneic blood transfusions

|

% of cases developing complications after transfusion

|

P value for reduction in postoperative complications | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | No of patients | Type of surgery | Intervention | Type of complication | Autologous | Allogeneic | |

| Busch et al, 19939 | 423 | Colorectal | Predeposit autologous donation | Infection | 27 | 25 | NS |

| Recurrence | 37 | 34 | NS | ||||

| Heiss et al, 1993 and 199410, 14 | 120 | Colorectal | Predeposit autologous donation | Infection | 12 | 27 | <0.05 |

| Recurrence | 17 | 29 | 0.11 | ||||

| Newman et al, 199711 | 70 | Knee replacement | Postoperative autologous salvage | Infection | 6 | 34 | <0.05 |

| Farrer et al, 199712 | 50 | Vascular | Intraoperative autologous salvage | Infection | 13 | 44 | 0.029 |

| Thomas et al, 200113 | 231 | Knee replacement | Postoperative autologous salvage | Infection | NA | NA | 0.036 |

| Readmission | NA | NA | 0.008 | ||||

NS=not significant.

NA=not available (ie not reported).

Footnotes

Competing interests: NB has received lecture honorariums and consulting fees from Ortho Biotech.

Extra tables appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Napier JA, Bruce M, Chapman J, Duguid JK, Kelsey PR, Knowles SM, et al. Guidelines for autologous transfusion. II. Perioperative haemodilution and cell salvage. British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force. Autologous Transfusion Working Party. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:768–771. doi: 10.1093/bja/78.6.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas MJG, Gillon J, Desmond MJ. An organisers' view. Transfusion. 1996;36:626–627. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36796323061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Network for the Advancement of Transfusion Alternatives. Transfusion medicine and alternatives to blood transfusion. Paris: R&J Éditions Médicales; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spiess BD, Counts RB, Gould SA. Perioperative transfusion medicine. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forgie MA, Wells PS, Laupacis A, Fergusson D. Preoperative autologous donation decreases allogeneic transfusion but increases exposure to all red blood cell transfusion—results of a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:610–616. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faught C, Wells P, Fergusson D, Laupacis A. Adverse effects of methods for minimizing perioperative allogeneic transfusion—a critical review of the literature. Transfus Med Rev. 1998;12:206–225. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(98)80061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumberg N, Heal JM. Transfusion immunomodulation. In: Anderson KC, Ness PM, editors. Scientific basis of transfusion medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W B Saunders; 2000. pp. 427–443. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bull BS, Bull MH. The salvaged blood syndrome: a sequel to mechanochemical activation of platelets and leukocytes? Blood Cells. 1990;16:5–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch ORC, Hop WCJ, Hoynck van Papendrecht MAW, Marquet RL, Jeekel J. Blood transfusions and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1372–1376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiss MM, Mempel W, Jauch KW, Delanoff C, Mayer G, Mempel M, et al. Beneficial effect of autologous blood transfusion on infectious complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Lancet. 1993;342:1328–1333. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92247-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman JH, Bowers M, Murphy J. The clinical advantages of autologous transfusion. A randomized, controlled study after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:630–632. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b4.7272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrer A, Spark JI, Scott DJ. Autologous blood transfusion: the benefits to the patient undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Nurs. 1997;15:111–115. doi: 10.1016/s1062-0303(97)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas D, Wareham K, Cohen D, Hutchings H. Autologous blood transfusion in total knee replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:669–673. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiss MM, Mempel W, Delanoff C, Jauch KW, Gabka C, Mempel M, et al. Blood transfusion-modulated tumor recurrence: first results of a randomized study of autologous versus allogeneic blood transfusion in colorectal cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1859–1867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healy JC, Frankforter SA, Graves BK, Reddy RL, Beck RB. Preoperative autologous blood donation in total hip arthroplasty—a cost effectiveness analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumberg N, Kirkley SA, Heal JM. A cost analysis of autologous and allogeneic transfusions in hip-replacement surgery. Am J Surg. 1996;171:324–330. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birkmeyer JD, Goodnough LT, AuBuchon JP, Noordsij PG, Littenberg B. The cost-effectiveness of preoperative autologous blood donation for total hip and knee replacement. Transfusion. 1993;33:544–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33793325048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feagan BG, Wong CJ, Kirkley A, Johnston DWC, Smith FC, Whitsitt P, et al. Erythropoietin with iron supplementation to prevent allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip joint arthroplasty—a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;133:845–854. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-11-200012050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faris PM, Ritter MA, Abels RI, Ball GV, Bernini PM, Bryant GL, et al. The effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on perioperative transfusion requirements in patients having a major orthopaedic operation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:62–72. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spahn DR, Casutt M. Eliminating blood transfusions—new aspects and perspectives. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:242–255. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeCastro RM. Bloodless surgery: establishment of a program for the special medical needs of the Jehovah's Witness community—the gynecologic surgery experience at a community hospital. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. 1999;180:1491–1495. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.