Abstract

Introduction: Infections caused by Acinetobacter baumannii are a major cause of health concerns in the hospital setting. Moreover, the presence of extreme drug resistance in A. baumannii has made the scenario more challenging due to limited treatment options thereby encouraging the researchers to explore the existing antimicrobial agents to combat the infections caused by them. This study focuses on the susceptibility of multi-drug-resistant A. baumannii (MDR-AB) strains to minocycline and also to colistin.

Methodology: A cross-sectional study was conducted from June 2022 to June 2023. One hundred isolates of A. baumannii obtained from various clinical samples were sent to Central Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chrompet, Chennai, India. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, 2022. For the standard antibiotics, the disc diffusion method was performed. For minocycline and colistin, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined using an epsilometer strip (E-strip) test.

Results: In this study, 100 isolates of A. baumannii were obtained, and 83% of the isolates were multi-drug-resistant. Among the MDR-AB, 50 (60%) were susceptible to minocycline and 40 (48%) were susceptible to colistin. Out of the 40 colistin-susceptible A. baumannii strains, 29 (73%) were susceptible to minocycline with a statistically significant P-value of <0.05. Among the 43 colistin-resistant A. baumannii strains, 21 (53%) were susceptible to minocycline with a statistically significant P-value of <0.05.

Conclusions: When taking into account the expense of treating carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria, colistin and minocycline can be used as an alternative drug as they have fewer side effects and are more affordable. Minocycline can be used as an alternative to colistin because it is feasible to convert from an injectable to an oral formulation.

Keywords: acinetobacter species, acinetobacter infections, e-strip test, colistin, minocycline, multidrug resistant acinetobacter baumannii (mdr-ab)

Introduction

Acinetobacter is a nonmotile Gram-negative coccobacillus that is most frequently found in soil, water, and sewage [1]. It was listed by the American Society of Infectious Diseases (IDSA) as one of the six most dangerous microorganisms and the second most frequent nonfermenting Gram-negative pathogen isolated from clinical samples after Pseudomonas aeruginosa [2]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019 listed carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) as an emerging threat, particularly in hospital-acquired infections (HAI) [3]. Despite a decrease in CRAB infections probably due to infection control practices and antimicrobial stewardship [4], CRAB remains a threat due to limited treatment options [5]. There are more than 30 species in the genus Acinetobacter, although A. baumannii and, to a lesser extent, Acinetobacter genospecies 3 and 13TU are mostly linked to nosocomial infections in the clinical environment [6].

Immunocompromised people frequently contract A. baumannii, especially if they had a prolonged hospital stay (>90 days). Long hospital stays are the most common risk factor for infections caused by this organism, which can also cause HAIs like catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), ventilator-associated events (VAE), surgical site infections (SSIs), catheter-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), and meningitis [7]. Furthermore, multi-drug resistance (MDR) and intrinsic resistance provide a worldwide medical concern [8]. MDR is defined as resistance to at least one drug in three or more antimicrobial categories. Carbapenems, the cornerstone of treatment in the past, are no longer successful in reducing the infections caused by this organism [9].

The percentage of organisms resistant to minocycline decreased during this time, falling from 56.5% in 2003-2005 to 30.5% in 2009-2012 [10]. The resistance towards colistin (2.8% in 2006-2008 and 6.9% in 2009-2012) and carbapenems (21.0% in 2003-2005 and 47.9% in 2009-2012) have more than doubled in the previous decade. Recent studies identified the percentage of resistance to minocycline and colistin as 7.2% and 1.7% respectively [11]. In the clinical environment, minocycline has been used as a second-line drug for a variety of bacterial infections. According to recent research, minocycline has gained importance in treating infections caused by multi-drug-resistant A. baumannii (MDR-AB) [12,13], due to the ability to boost colistin's efficacy against MDR-AB isolates [14]. Minocycline has better pharmacokinetic activity than other tetracyclines [15]. Thus, our study was conducted to determine the susceptibility of A. baumannii, with special reference to minocycline.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from June 2022 to June 2023 in the Central Laboratory, Department of Microbiology at a tertiary care hospital, Chennai, South India, after obtaining Institutional Human Ethics Committee (IHEC) approval.

Inclusion criteria

Nonrepetitive MDR-AB isolated from the culture samples sent to the Central Laboratory, Department of Microbiology during the study period were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Repetitive samples and highly susceptible A. baumannii were excluded from the study.

One hundred isolates of A. baumannii were obtained by conventional methods from various clinical samples such as wound swabs, ear swabs, throat swabs, pus, endotracheal aspirate (ET), blood, sputum, tissue (synovial tissue and lung tissue biopsy), and urine samples. Specimens were cultured overnight at 37 °C on 5% sheep blood agar and MacConkey agar plates. Gram staining was performed on the colonies after 24 hours, which revealed the presence of Gram-negative coccobacilli by microscopy. The biochemical tests such as catalase test, oxidase test, indole test, citrate utilization test, urease production test, triple sugar iron test, mannitol motility and fermentation test, and phenylalanine deaminase test were used to confirm the identification of the organism, as per standard operating procedure [16]. The reagents and media were obtained from HiMedia, Mumbai, India. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method [16] and interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, 2022. The following drugs were used: ceftazidime (30 µg), ceftriaxone (30 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), cefepime (30 µg), piperacillin(100 µg)-tazobactam(10 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), trimethoprim (1.25 µg)-sulfamethoxazole(23.75 µg), amikacin (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), tobramycin (10 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), imipenem (10 µg), and meropenem (10 µg) [17]. After streaking the colonies on Muller-Hinton agar, minocycline and colistin epsilometer strips (E-strip) were placed on two separate plates [16]; observed for minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC); and interpreted as per CLSI guidelines 2022 [17]. The discs and strips were obtained from HiMedia. The controls used were satisfactory (Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, procured from HiMedia). The automated system - Vitek-2 compact (Vitek-2 GN card) was used for further confirmation of the organism and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (bioMérieux Inc., Durham, NC).

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel. The data were analyzed using SPSS, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and a P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were presented in tables as frequency and percentage.

Results

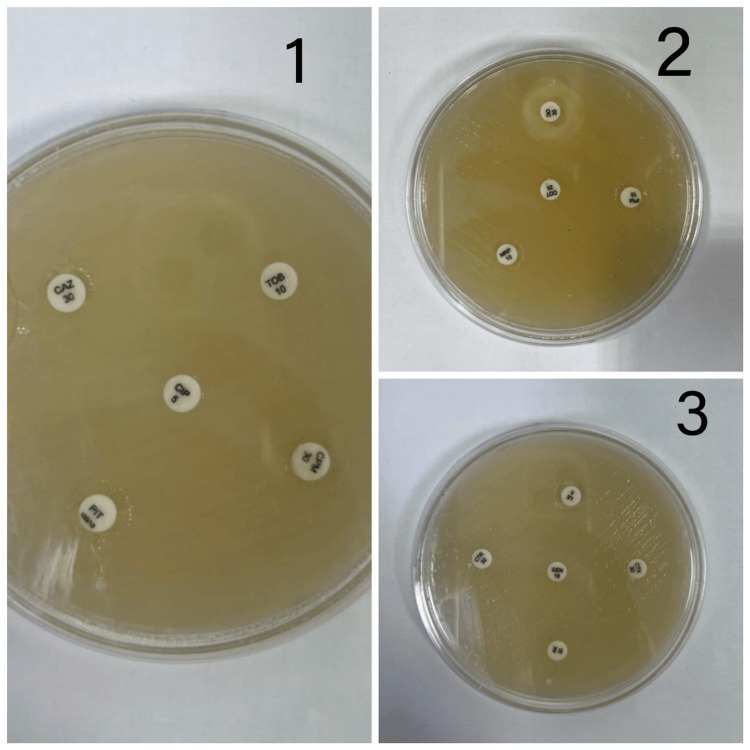

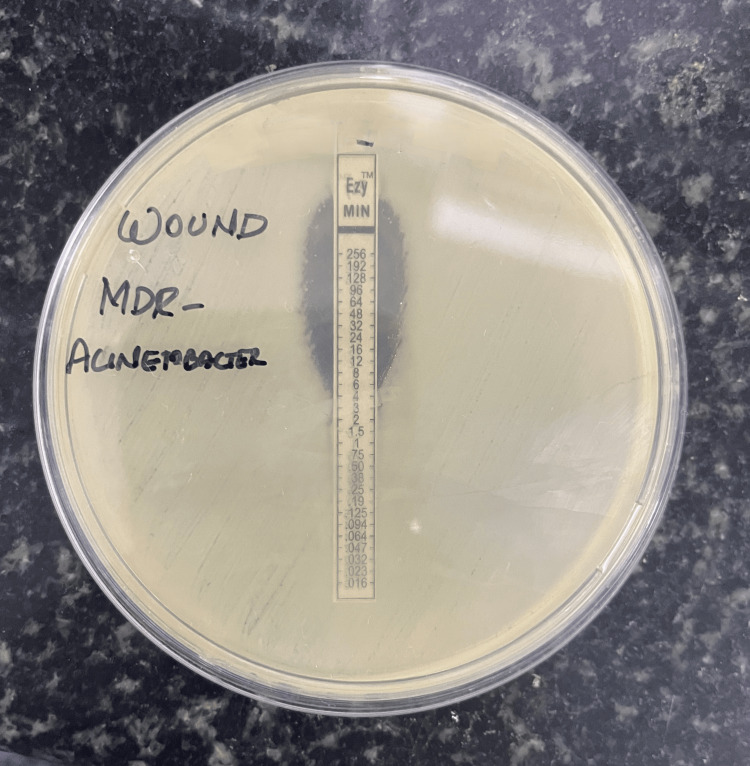

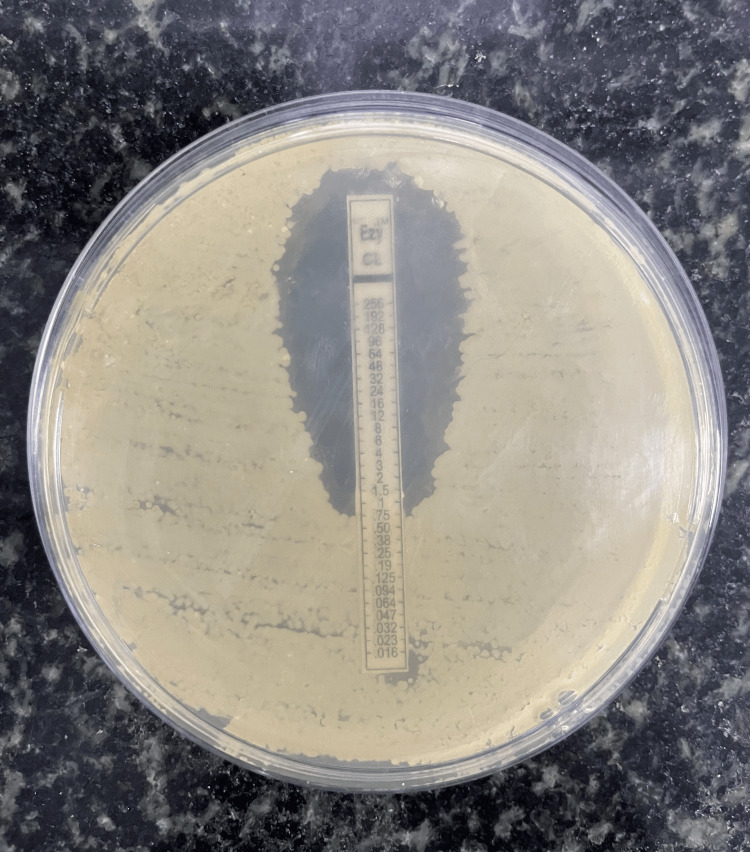

This study comprises 100 isolates of A. baumannii from a variety of clinical specimens such as wound swabs, ear swabs, throat swabs, pus, ET aspirate, blood, sputum, tissue (synovial tissue, lung tissue biopsy), and urine (Table 1). Out of the 100 A. baumannii isolates, 83% were MDR identified by the Kirby-Bauer disc-diffusion method (Figure 1). The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of MDR-AB is depicted in Table 2. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of MDR-AB to minocycline and colistin is depicted in Tables 3-4 and Figures 2-3, respectively.

Table 1. Acinetobacter baumannii among various clinical samples.

| Sample | Acinetobacter baumannii (N = 100) (%) |

| Wound swab | 38 |

| Ear swab | 2 |

| Throat swab | 2 |

| Pus | 12 |

| ET | 5 |

| Blood | 12 |

| Sputum | 15 |

| Tissue (synovial tissue and lung tissue biopsy) | 4 |

| Urine | 10 |

Table 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of MDR-AB.

MDR-AB, multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

| Antibiotics | Susceptible, n (%) | Intermediate, n (%) | Resistant, n (%) | Total |

| Ceftazidime | 34 (41) | 0 | 49 (59) | 83 |

| Doxycycline | 42 (51) | 1 (1) | 40 (48) | 83 |

| Levofloxacin | 51 (61) | 3 (4) | 29 (35) | 83 |

| Meropenem | 32 (38) | 1 (1) | 51 (61) | 83 |

| Imipenem | 30 (36) | 2 (3) | 51 (61) | 83 |

| Ceftriaxone | 21 (25) | 1 (1) | (74) | 83 |

| Cefotaxime | 25 (30) | 1 (1) | 57 (69) | 83 |

| Piperacillin tazobactam | 46 (56) | 1 (1) | 36 (43) | 83 |

| Cotrimoxazole | 36 (43) | 1 (1) | 46 (56) | 83 |

| Cefepime | 31 (37) | 1 (1) | 51 (62) | 83 |

| Gentamicin | 42 (51) | 2 (2) | 39 (47) | 83 |

| Tobramycin | 46 (55) | 1 (1) | 36 (44) | 83 |

| Amikacin | 38 (46) | 2 (2) | 43 (52) | 83 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 44 (53) | 1 (1) | 38 (46) | 83 |

Table 3. Susceptibility of MDR-AB to minocycline.

MDR-AB, multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

| Drug | Susceptible, n (%) | Intermediate, n (%) | Resistant, n (%) | Total |

| Minocycline | 50 (60) | 20 (24) | 13 (16) | 83 |

Table 4. Susceptibility of MDR-AB to colistin.

MDR-AB, multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

| Drug | Susceptible, n (%) | Intermediate, n (%) | Resistant, n (%) | Total |

| Colistin | 40 (48) | 25 (30) | 18 (22) | 83 |

Figure 1. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of MDR-Acinetobacter baumannii by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method.

The following drugs were used:

(1) Ceftazidime (CAZ), tobramycin (TOB), ciprofloxacin (CIP), cefepime (CPM), and piperacillin-tazobactam (PIT)

(2) Doxycycline (DO), imipenem (IPM), cotrimoxazole (COT), and meropenem (MRP)

(3) Ceftriaxone (CTR), levofloxacin (LE), gentamicin (GEN), cefotaxime (CTX), and amikacin (AK)

MDR, multi-drug resistant

Figure 2. Susceptibility pattern of Acinetobacter baumannii to minocycline: epsilometer strip (E-strip) method.

Figure 3. Susceptibility pattern of Acinetobacter baumannii to colistin: epsilometer strip (E-strip) method.

Table 5 shows the comparison of susceptibility to minocycline and colistin. Among the 40 colistin-susceptible strains, 29 (73%) showed susceptibility to minocycline, with a statistically significant P-value < 0.05, and also, out of the 43 colistin-resistant strains, 21 (53%) showed susceptibility to minocycline, with a statistically significant P-value < 0.05.

Table 5. Comparison of susceptibility to minocycline and colistin for MDR-AB.

MDR-AB, multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

| Drug | Minocycline susceptible, n (%) | Minocycline resistant, n (%) | Total |

| Colistin susceptible | 29 (73) | 11 (27) | 40 |

| Colistin resistant | 21 (53) | 22 (47) | 43 |

| Total | 50 | 33 | 83 |

Discussion

CRAB has become more common though carbapenems are effective treatments for MDR-AB infections. In Asia, 60% of the isolates were CRAB and pan-drug-resistant A. baumannii. In the United States and Europe, 65% of the isolates were identified as CRAB [18]. Numerous tigecycline resistance mechanisms in A. baumannii can be circumvented by minocycline. Additionally, minocycline has good in vitro action against drug-resistant A. baumannii and favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. Minocycline is considered to be an effective alternative against MDR infections, particularly in conditions where limited antimicrobials are accessible and in patients requiring prolonged hospitalization. Akers et al. demonstrated a favorable clinical outcome in such patients with minocycline in their trial in a military center against MDR Acinetobacter spp. [19]. Flamm et al. showed minocycline to be progressively efficient against MDR pathogens in a comparison investigation using tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline. 70% of MDR organisms were sensitive to minocycline in their study [20]. Greig and Scott detected a susceptibility of 80% toward minocycline among MDR Acinetobacter spp. [21].

Fragkou et al. found that the clinical and microbiological success rates after minocycline treatment were 72.6% and 60.2%, respectively [22]. In our study, out of 83 MDR-AB, 50 (60%) were susceptible to minocycline, 20 (24%) were intermediate, and 13 (16%) were resistant, which implies minocycline is effective against multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter spp. either by oral or by intravenous (IV) route. Greig and Scott explained the potential role of IV minocycline efficacy against MDR Acinetobacter spp. especially when combined with a second antibacterial agent [21]. IV minocycline has been approved by the US FDA for the treatment of culture-positive MDR Acinetobacter species in hospitalized patients. The "Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now Act (GAIN Act)" designates its approval as a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) [23]. Fragkou PC et al. in the systematic review of the outcome of minocycline treatment towards MDR-AB emphasized a substantial percentage of success in clinical (72.6%) and microbiological (60.2%) aspects [22]. In the study conducted by Kuo SC et al. approximately 20% of A. baumannii isolates were resistant to minocycline [24]. However, its therapeutic appeal has been increased by the simplicity of switching from IV to oral formulations. This is especially true for patients who are hard to treat and have resistant Acinetobacter infections, as the data that is now available supports the efficacy of therapy in these tough clinical situations [15].

Colistin is used as a rescue therapy for severe infections and is regarded as one of the final therapeutic alternatives for the treatment of MDR-AB infections [25,26]. Due to increasing resistance to colistin and due to its toxicity and higher cost, we can use minocycline as an alternative to colistin in most multi-drug-resistant Acinetobacter cases. The most commonly used therapeutic combinations for MDR-AB include carbapenems, tigecycline, minocycline, polymyxins, and daptomycin. Bowers et al. in a study, where minocycline and polymyxin B were used as a combination on pan-drug-resistant A. baumannii found out that the MIC of each medication significantly dropped [27]. As a result, either as a single drug or in combination with other drugs it is very effective against MDR Acinetobacter spp.

Limitations of the study

This study includes only bacterial isolates from the lab, and hence, patient details, clinical outcomes, and correlation were not analyzed. The comparison of various antimicrobial susceptibility methods for colistin such as the micro-broth dilution method was not performed.

Conclusions

Choosing the right medications is still crucial in treating infections caused by multi-drug-resistant organisms such as A. baumannii. In certain circumstances, minocycline can be used in the place of colistin. This is notably true for patients with MDR organisms hospitalized in intensive care units, where minocycline has fewer side effects and is more affordable. When taking into account the expense of treating Gram-negative bacteria that produce carbapenemases, colistin, and minocycline can be taken as an alternative drug. A potential therapeutic niche for minocycline would be the conversion of an injectable mode to oral formulation in stable patients who need a longer course of treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Central Diagnostic Laboratory and the Central Research Laboratory, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital (SBMCH) for providing the laboratory facilities.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. The Institutional Human Ethics Committee of Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital (SBMCH) issued approval 002/SBMCH/IHEC/2023/1920.

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Aishwarya J. Ramalingam, Punithavathi Velmurugan, Chitralekha Saikumar

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Aishwarya J. Ramalingam, Punithavathi Velmurugan

Drafting of the manuscript: Aishwarya J. Ramalingam, Punithavathi Velmurugan, Chitralekha Saikumar

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Aishwarya J. Ramalingam, Chitralekha Saikumar

Supervision: Aishwarya J. Ramalingam, Chitralekha Saikumar

References

- 1.Recent advances in the pursuit of an effective Acinetobacter baumannii vaccine. Gellings PS, Wilkins AA, Morici LA. Pathogens. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/pathogens9121066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevalence & antimicrobial profile of Acinetobacter Spp. isolated from tertiary care hospital. Kaur R, Kaur S, Oberoi L, Singh K, Nagpal N, Kaur M. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2021;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. [ Apr; 2020 ]. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- 4.Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in U.S. hospitalized patients, 2012-2017. Jernigan JA, Hatfield KM, Wolford H, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1309–1319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epidemiology and outcomes associated with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a retrospective cohort study. Vivo A, Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, et al. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:491. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07436-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Multidrug resistance pattern of Acinetobacter species isolated from clinical specimens referred to the Ethiopian Public Health Institute: 2014 to 2018 trend anaylsis. Ayenew Z, Tigabu E, Syoum E, Ebrahim S, Assefa D, Tsige E. PLoS One. 2021;16:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nosocomial outbreak of infection with pan-drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a tertiary care university hospital. Valencia R, Arroyo LA, Conde M, et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:257–263. doi: 10.1086/595977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antibiograms of multidrug-resistant clinical Acinetobacter baumannii: promising therapeutic options for treatment of infection with colistin-resistant strains. Li J, Nation RL, Owen RJ, Wong S, Spelman D, Franklin C. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;1:594–598. doi: 10.1086/520658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Confronting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a review. Neonakis IK, Spandidos DA, Petinaki E. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;37:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secular trends in Acinetobacter baumannii resistance in respiratory and blood stream specimens in the United States, 2003 to 2012: a survey study. Zilberberg MD, Kollef MH, Shorr AF. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:21–26. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geographic patterns of Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem resistance in the Asia-Pacific Region: results from the Antimicrobial Testing Leadership and Surveillance (ATLAS) program, 2012-2019. Lee YL, Ko WC, Hsueh PR. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;127:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minocycline--an old drug for a new century: emphasis on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Acinetobacter baumannii. Bishburg E, Bishburg K. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Susceptibility of acinetobacter strains isolated from deployed U.S. military personnel. Hawley JS, Murray CK, Griffith ME, McElmeel ML, Fulcher LC, Hospenthal DR, Jorgensen JH. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:376–378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00858-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.In vitro effect of minocycline and colistin combinations on imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Tan TY, Ng LS, Tan E, Huang G. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:421–423. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minocycline, focus on mechanisms of resistance, antibacterial activity, and clinical effectiveness: back to the future. Asadi A, Abdi M, Kouhsari E, et al. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patricia MT. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2022. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI Document M100, 32nd edition. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the community: a scoping review. Kelly AM, Mathema B, Larson EL. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tetracycline susceptibility testing and resistance genes in isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii-Acinetobacter calcoaceticus complex from a U.S. military hospital. Akers KS, Mende K, Yun HC, Hospenthal DR, Beckius ML, Yu X, Murray CK. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2693–2695. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01405-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minocycline activity tested against Acinetobacter baumannii complex, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Burkholderia cepacia species complex isolates from a global surveillance program (2013) Flamm RK, Castanheira M, Streit JM, Jones RN. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;85:352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Intravenous minocycline: a review in Acinetobacter infections. Greig SL, Scott LJ. Drugs. 2016;76:1467–1476. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The role of minocycline in the treatment of nosocomial infections caused by multidrug, extensively drug and pandrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review of clinical evidence. Fragkou PC, Poulakou G, Blizou A, et al. Microorganisms. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minocycline: the second important antimicrobial in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii infections. Nair AS. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34:140–141. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_156_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emergence of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii complex over 10 years: nationwide data from the Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (TSAR) program. Kuo SC, Chang SC, Wang HY, et al. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Risk factors for the first episode of Acinetobacter baumannii resistant to colistin infection and outcome in critically ill patients. Mantzarlis K, Makris D, Zakynthinos E. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69:35–40. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colistin treatment for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative infections in children: caution required for nephrotoxicity. Ustundag G, Oncel EK, Sahin A, Keles YE, Aksay AK, Ciftdogan DY. Sisli Etfal Hastan Tip Bul. 2022;56:427–434. doi: 10.14744/SEMB.2021.69851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assessment of minocycline and polymyxin B combination against Acinetobacter baumannii. Bowers DR, Cao H, Zhou J, Ledesma KR, Sun D, Lomovskaya O, Tam VH. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:2720–2725. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04110-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]