Abstract

Background

Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia occurs because of interference with normal temperature regulation by anaesthetic drugs and exposure of skin for prolonged periods. A number of different interventions have been proposed to maintain body temperature by reducing heat loss. Thermal insulation, such as extra layers of insulating material or reflective blankets, should reduce heat loss through convection and radiation and potentially help avoid hypothermia.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pre‐ or intraoperative thermal insulation, or both, in preventing perioperative hypothermia and its complications during surgery in adults.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2014, Issue 2), MEDLINE, OvidSP (1956 to 4 February 2014), EMBASE, OvidSP (1982 to 4 February 2014), ISI Web of Science (1950 to 4 February 2014), and CINAHL, EBSCOhost (1980 to 4 February 2014), and reference lists of articles. We also searched Current Controlled Trials and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials of thermal insulation compared to standard care or other interventions aiming to maintain normothermia.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors extracted data and assessed risk of bias for each included study, with a third author checking details. We contacted some authors to ask for additional details. We only collected adverse events if reported in the trials.

Main results

We included 22 trials, with 16 trials providing data for some analyses. The trials varied widely in the type of patients and operations, the timing and measurement of temperature, and particularly in the types of co‐interventions used. The risk of bias was largely unclear, but with a high risk of performance bias in most studies and a low risk of attrition bias. The largest comparison of extra insulation versus standard care had five trials with 353 patients at the end of surgery and showed a weighted mean difference (WMD) of 0.12 ºC (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.31; low quality evidence). Comparing extra insulation with forced air warming at the end of surgery gave a WMD of ‐0.67 ºC (95% CI ‐0.95 to ‐0.39; very low quality evidence) indicating a higher temperature with forced air warming. Major cardiovascular outcomes were not reported and so were not analysed. There were no clear effects on bleeding, shivering or length of stay in post‐anaesthetic care for either comparison. No other adverse effects were reported.

Authors' conclusions

There is no clear benefit of extra thermal insulation compared with standard care. Forced air warming does seem to maintain core temperature better than extra thermal insulation, by between 0.5 ºC and 1 ºC, but the clinical importance of this difference is unclear.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Bedding and Linens, Protective Clothing, Body Temperature Regulation, Body Temperature Regulation/drug effects, Hypothermia, Hypothermia/prevention & control, Intraoperative Complications, Intraoperative Complications/prevention & control, Perioperative Care, Perioperative Care/methods, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Insulation for preventing hypothermia during operations

Review question

We wanted to find out the effects of extra insulation on preventing hypothermia and its complications for adults having an operation.

Background

People can get cold during operations, particularly because of the drugs used as anaesthetics. This can sometimes cause potentially dangerous heart problems. The cold can also make people shiver and feel uncomfortable after an operation. Ways have therefore been developed to try to keep people warm during an operation. One way is to use reflective blankets or clothing as extra insulation.

Study characteristics

We looked at the evidence up to February 2014 and found 22 studies involving several hundred patients. The studies involved people aged over 18 years having routine or emergency surgery. We disregarded studies where people were deliberately kept cold during the operation, where they were having head surgery or skin grafts, or where the person was having a procedure under local anaesthetic.

We looked at studies comparing what happened when using reflective blankets or clothing against what happened when someone had normal care, using non‐reflective blankets or clothing.

We also looked at studies comparing what happened when using a machine to force warm air through the person’s blankets (forced air warming) against what happened when using reflective blankets or clothing.

Key results

There is no clear evidence that using reflective blankets or clothing increases a person’s temperature compared with what happens when someone has usual care.

There is some evidence that using forced air warming increases a person’s temperature compared with what happens when using reflective blankets or clothing. The temperature increase was between 0.5 ºC and 1 ºC. It is unclear how this temperature difference would reduce the consequences of coldness, with uncertain effects on blood loss, shivering and time spent in recovery. We were unable to find sufficient information to look at adverse effects of insulation or warming, or major events affecting the heart or circulatory system.

Quality of the evidence

Most of the evidence was low quality. We were particularly concerned about the potential for skewed results from operating theatre staff changing their behaviour when they knew ways of keeping the patient warm had changed.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Additional insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia.

| Additional insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia Settings: Intervention: additional insulation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Additional insulation | |||||

| Temperature after 30 minutes ºC Follow‐up: 30 minutes | The mean temperature after 30 minutes in the control groups was 36.1 ºC1 | The mean temperature after 30 minutes in the intervention groups was 0.11 higher (0.02 lower to 0.23 higher) | 250 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| Temperature after 1 hour ºC Follow‐up: 1 hour | The mean temperature after 1 hour in the control groups was 35.9 ºC1 | The mean temperature after 1 hour in the intervention groups was 0.02 higher (0.13 lower to 0.16 higher) | 264 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| Temperature at the end of procedure or arrival in PACU ‐ Simple design studies ºC | The mean temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU‐ simple design studies in the control groups was 36.0 ºC | The mean temperature at the end of procedure or arrival in PACU ‐ Simple design studies in the intervention groups was 0.12 higher (0.07 lower to 0.31 higher) | 353 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

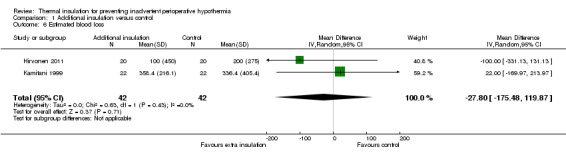

| Estimated blood loss mls | The mean estimated blood loss in the control groups was 268 mls | The mean estimated blood loss in the intervention groups was 27.8 lower (175.48 lower to 119.87 higher) | 84 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | ||

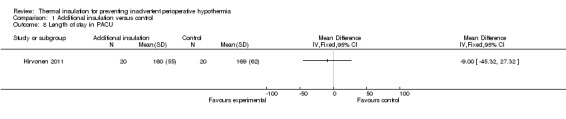

| Length of stay in PACU | The mean length of stay in PACU in the intervention groups was 9 lower (45.32 lower to 27.32 higher) | 40 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ low2,4 | |||

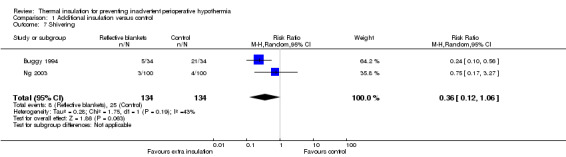

| Shivering observation by staff | Study population | RR 0.36 (0.12 to 1.06) | 268 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | ||

| 187 per 1000 | 67 per 1000 (22 to 198) | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| 329 per 1000 | 118 per 1000 (39 to 349) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Mean of endpoint scores 2 No blinding and unclear allocation concealment 3 Moderate heterogeneity with no clear explanation 4 Wide confidence intervals with data from only a small number of the patients in trials 5 Not all trials blinded, also unclear allocation concealment

Summary of findings 2. Additional insulation compared to forced air warming for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia.

| Additional insulation compared to forced air warming for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia Settings: Intervention: additional insulation Comparison: forced air warming | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| forced air warming | Additional insulation | |||||

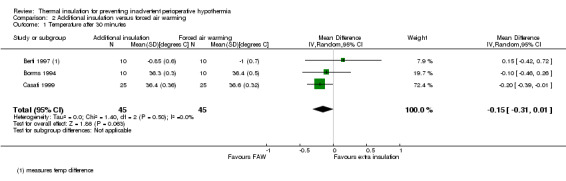

| Temperature after 30 minutes ºC | The mean temperature after 30 minutes in the control groups was 36.5 ºC1 | The mean temperature after 30 minutes in the intervention groups was 0.15 lower (0.31 lower to 0.01 higher) | 90 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

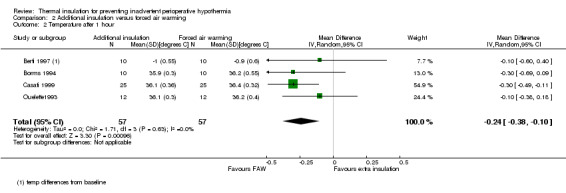

| Temperature after 1 hour ºC | The mean temperature after 1 hour in the control groups was 36.3 ºC | The mean temperature after 1 hour in the intervention groups was 0.24 lower (0.38 to 0.1 lower) | 114 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

| Temperature at the end of procedure or arrival in PACU ‐ Simple design ºC | The mean temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU ‐ simple design in the control groups was 36.3 ºC1 | The mean temperature at the end of procedure or arrival in PACU ‐ Simple design in the intervention groups was 0.67 lower (0.95 to 0.39 lower) | 330 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | ||

| Estimated blood loss mls | The mean estimated blood loss in the control groups was 330 mls | The mean estimated blood loss in the intervention groups was 15.06 higher (67.23 lower to 97.35 higher) | 80 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | ||

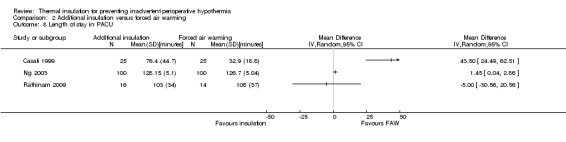

| Length of stay in PACU | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 280 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5 | |

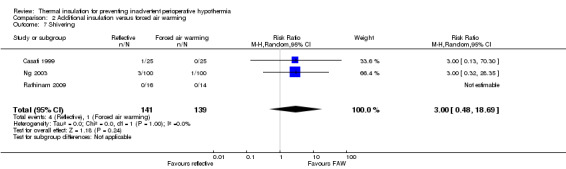

| Shivering observation by staff | 7 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (3 to 131) | RR 3 (0.48 to 18.69) | 280 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 mean of endpoint values 2 Lack of blinding and unclear allocation concealment 3 unexplained heterogeneity present, but unlikely to change the conclusion 4 wide confidence interval, probably including important differences 5 unexplained heterogeneity

Background

Description of the condition

Regulation of temperature

Body temperature is usually maintained between 36.5 ºC and 37.5 ºC by balancing the body's heat loss and gains. Heat is gained as a product of metabolism, including that associated with muscular activity, and is lost through convection, conduction and radiation from the skin as well as evaporation through sweating.

To maintain this balance, information from temperature sensors in deep tissues and the skin is processed in the brain. Heat loss is increased through sweating and increased blood flow through the skin. Heat loss is minimised by reducing blood flow through the skin and heat production is increased mainly by inducing muscular activity (shivering).

A useful concept in thinking about heat regulation is that the body has a central compartment comprising the major organs, where temperature is tightly regulated, and a peripheral compartment where temperature varies more widely. Typically the peripheries may be 2 ºC to 4 ºC cooler than the core compartment.

The effects of perioperative care and anaesthesia on thermal regulation

Exposure of the skin and internal organs during the perioperative period can increase heat loss, and the use of cool intravenous and irrigation fluids and inspired or insufflated (blown into body cavities) gases may directly cool patients.

Sedatives and anaesthetic agents inhibit the normal response to cold, where surface blood vessels are constricted, effectively resulting in more blood flow to the peripheries and increased heat loss. During the early part of anaesthesia these effects mean that the core temperature decreases rapidly as a result of heat being redistributed from the central compartment to the peripheral compartment. Early heat loss is followed by a more gradual decline reflecting ongoing heat loss.

With epidural or spinal analgesia, there is peripheral blockade of vasoconstriction below the level of the nerve block resulting in ongoing heat loss. Paralysis below the level of the block prevents shivering.

The risk of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia varies widely, for example there are reports from audits of a risk of 1.5% (Al‐Qahtani 2011) to 20% (Harper 2008). The patients who are most susceptible to heat loss are the elderly, patients with higher anaesthetic risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade 3 to 4), people with cachexia (increased metabolism associated with cancer), burn victims, people with hypothyroidism and those affected by corticoadrenal insufficiency.

Perioperative hypothermia complications

Hypothermia, by altering various systems and functions, may result in an increase in morbidity. Patients often comment on subsequent shivering upon awakening from anaesthesia as being one of the most uncomfortable immediate postoperative experiences. Shivering originates as a response to cold and is the result of involuntary muscular activity that has the objective of increasing metabolic heat (Sessler 2001).

Cardiac complications are the principal cause of morbidity during the postoperative phase. Prolonged ischaemia (reduced blood flow) is usually associated with cellular damage. For this reason it is likely to be important to treat factors like body temperature that may lead to such complications. Hypothermia stimulates the release of noradrenaline resulting in peripheral vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) and hypertension (Sessler 1991; Sessler 2001), factors favouring or increasing the chances of myocardial ischaemia. However, there is little direct clinical evidence proving an association between hypothermia and perioperative cardiovascular events. A frequently cited study (Frank 1997) actually included only three cases of myocardial infarction.

Some studies have shown that intraoperative hypothermia accompanied by vasoconstriction constitutes an independent factor that slows wound healing and increases the risk of surgical wound infections (Kurz 1996; Melling 2001).

Even moderate hypothermia (35 ºC) can alter physiological coagulation mechanisms by affecting platelet function and modifying enzymatic reactions. Decreased platelet activity produces an increase in bleeding and a greater need for transfusion (Rajagopalan 2008). Moderate hypothermia can also reduce the metabolic rate, manifesting as a prolonged effect of certain drugs used during anaesthesia and some uncertainty about their effects. This is particularly significant in elderly patients (Heier 1991; Heier 2006; Leslie 1995).

Due to the above reasons, inadvertent non‐therapeutic hypothermia is considered an adverse effect of both general and regional anaesthesia (Bush 1995; Putzu 2007; Sessler 1991). The monitoring of body temperature is therefore frequently used to aid in maintaining normothermia during surgery and for timely detection of the appearance of unintended hypothermia.

Description of the intervention

The objective of preserving patients' body heat during anaesthesia and surgery is to minimize heat loss. This can be achieved by reducing radiation, conduction and convection from the skin, evaporation from exposed surgical areas, and cooling caused by the introduction of cold intravenous fluids and irrigation fluids. The use of cold gases for respiration or insufflation of body cavities would be unlikely to have a significant effect on body temperature because of the low heat capacity of gases (Birch 2011). Interventions that have been used to maintain body temperature can be classified as follows.

Interventions to decrease redistribution of heat and subsequent heat loss (i.e. preoperative pharmacologic vasodilatation and prewarming the skin prior to anaesthesia).

Passive warming systems aimed at reducing heat loss and thus preventing hypothermia, including changes to environmental temperature, passive insulation by covering the exposed body surface, and a closed or semi‐closed anaesthesia circuit with low flows.

Active warming systems aimed at transferring heat to the patient. The effectiveness of these systems might depend on various factors such as the design of the machine, the type of heat transfer, placement of the system over the patient and the total body area covered in the heat exchange. The following systems are used for active warming: infrared lights, electric blankets, mattresses or blankets with warm water circulation, forced air warming or convective air warming transfer, warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids, warming and humidifying of anaesthetic air, and carbon dioxide (CO2) warming in laparoscopic surgery. Intravenous nutrients have also been proposed as a way of inducing increased metabolism and thus energy production.

Why it is important to do this review

The clinical effectiveness of the different types of patient warming devices that can be used has been assessed in an extensive guideline commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK (NICE 2008). The report concludes that there is sufficient evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness for recommendations to be made on the use of forced air warming to prevent and treat perioperative hypothermia. Nevertheless, most of the data comes from intermediate outcomes such as temperature. The search for evidence covered until year 2007 and so it needs updating.

This review forms one of a number of reviews in this area. There are now Cochrane reviews covering warming of gases used in minimally invasive abdominal surgery (Birch 2011); the use of warmed and humidified inspired gases in ventilated adults and patients (Kelly 2010); and a review in preparation on active warming (Urrútia 2011). The remaining areas to be covered are:

pre‐ or intraoperative thermal insulation, or both;

pre‐ or intraoperative warming, or both, of intravenous and irrigation fluids;

pre‐ or intraoperative pharmacological interventions, or both, including intravenous nutrients;

postoperative treatment of inadvertent hypothermia.

Objectives

To assess the effects of pre‐ or intraoperative thermal insulation, or both, in preventing perioperative hypothermia and its complications during surgery in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐randomized controlled trials (such as allocation by alternation) of interventions used in the preoperative period (one hour before induction of anaesthesia), the intraoperative period (total anaesthesia time), or both.

Types of participants

We included adults (over 18 years of age) undergoing elective and emergency surgery (including surgery for trauma) with general or regional (central neuraxial block) anaesthesia, or both.

We planned to analyse subgroups, if data allowed, based on patient demographics (older people > 80 years, pregnant women, ASA score 1 and 2 versus higher); duration of anaesthesia, under and over three hours; and type (including opening thorax or abdomen versus not) and urgency (emergency or elective) of surgery.

The following groups were not covered:

patients who had been treated with therapeutic hypothermia e.g. use of cardiopulmonary bypass;

patients undergoing operative procedures under local anaesthesia;

patients with isolated severe head injuries resulting in impaired temperature control;

patients undergoing surgery for burns (e.g. for skin grafting).

Types of interventions

For this review, thermal insulation was defined as interventions deliberately designed to prevent heat loss (reflective blankets or clothing) as compared to usual care (cotton sheets or blankets, wool blankets, other non‐reflective textiles).

The comparisons of interest were thermal insulation compared to:

other methods of thermal insulation (e.g. blankets versus hats);

pre‐ or intraoperative warming, or both, of intravenous and irrigation fluids;

pre‐ or intraoperative warming, or both, of inspired and insufflated gases;

pre‐ or intraoperative pharmacological interventions, or both, including intravenous nutrients;

pre‐ or intraoperative active warming, or both.

We included studies using any co‐interventions so long as the only difference between the study groups was the intervention of interest.

Types of outcome measures

These outcomes were not used as inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies but as a template for data collection.

Primary outcomes

Temperature measured direct at the tympanic membrane, bladder, oesophagus, pulmonary artery, nasopharynx, or rectum at 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes after induction and at the end of the surgical procedure or arrival at the post‐anaesthetic care unit

Major cardiovascular complications (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke and non‐fatal cardiac arrest)

Secondary outcomes

Infection and complications of the surgical wound (wound healing and dehiscence), as defined by the study authors

Pressure ulcers, as defined by the study authors

Bleeding complications (blood loss, transfusions, coagulopathy)

Other cardiovascular complications (bradycardia, hypotension, arrhythmias)

Patient reported outcomes (i.e. shivering, anxiety, comfort in postsurgical wake‐up, etc.)

All cause mortality at the end of the study

Length of stay (in post‐anaesthesia care unit, hospital)

Unplanned high dependency or intensive care admission

Adverse effects

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted a single search across three reviews on this topic (this and others on warming of intravenous and irrigation fluids, and treatments for inadvertent hypothermia) with the following strategy, which was refined following a cross check with studies included in the NICE guideline on this topic (NICE 2008).

Electronic searches

For identifying eligible randomized clinical trials we searched the following electronic databases in June 2011, June 2012, February 2013, November 2013 and February 2014: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (February 2014), see Appendix 1; MEDLINE, OvidSP (1956 to February 2014), see Appendix 2; EMBASE, OvidSP (1982 to February 2014), see Appendix 3; ISI Web of Science (1950 to February 2014), see Appendix 4; and CINAHL, EBSCOhost (1980 to February 2014), see Appendix 5. For searching the databases we used both subject headings and free text terms with no language or date restrictions. We adapted our MEDLINE search strategy for searching all other databases.

Searching other resources

For identifying any additional published, unpublished and ongoing studies, we searched the Science Citation Index and checked the references of the relevant studies and reviews. We also searched the databases of ongoing trials such as:

Current Controlled Trials;

Clinicaltrials.gov.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

PA, GC and SW independently sifted the results of the literature searches to identify relevant studies such that each study was checked by two people. This was done once for all interventions, and the interventions were recorded on a data extraction form. If an article could not be excluded by the review of the title and abstract, we retrieved a full copy of the article. For an updated search in June 2012, sifting was with the help of another colleague (Michael Lowe) who is not a full author. The reasons for exclusion of articles that had been retrieved in full were recorded. Disagreements about inclusion or exclusion were resolved by discussion involving another author (AS), if necessary.

Data extraction and management

PA, GC and SW extracted relevant data independently onto a data extraction form (see Appendix 6), resolving disagreements by discussion or by referring to a clinical expert (AS). GC and PA entered data into RevMan and SW checked for transcription errors.

We extracted the following data.

General information, such as title, authors, contact address, publication source, publication year, country.

Methodological characteristics and study design.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of study participants.

Description of the intervention and the control. We collected information about the kind of surgery, duration, surgical team experience and prophylactic antibiotic administration, when available.

Outcome measures, as noted above.

Results for each study group.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We (PA, GC and SW) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving another assessor.

We considered a trial as having a low risk of bias if all of the following criteria were assessed as adequate. We considered a trial as having a high risk of bias if one or more of the following criteria was not assessed as adequate.

Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias). We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence when reported in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. We assessed the methods as: adequate (any truly random process e.g. random number table, computer random number generator); inadequate (any non‐random process e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or unclear.

Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias). We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence when reported in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen, in advance of or during recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed the methods as: adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes); inadequate (open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation, date of birth); or unclear.

Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias). We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. Where blinding was not possible, we assessed whether the lack of blinding was likely to have introduced bias. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We assessed the methods as: adequate; inadequate; or unclear.

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes. We assessed the methods as: adequate; inadequate; or unclear.

Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations). We described for each included study and for each outcome the completeness of the data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total number of randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook. We considered intention to treat as adequate if all dropouts or withdrawals were accounted for, and as inadequate if the number of dropouts or withdrawals was not stated, or if the reasons for any dropouts or withdrawals were not stated.

Selective reporting. We reported for each included study which outcomes of interest were and were not reported. We did not search for trial protocols.

Other bias. We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias. We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias: yes; no; or unclear.

With reference to (1) to (7) above, we considered the likely magnitude and direction of the bias when interpreting the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses (see 'Sensitivity analysis').

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data using risk ratios and continuous data using mean differences. For both we used 95% confidence intervals (CI) around the point estimate.

One trial (Shao 2012) had a complex factorial design with 32 treatment groups each receiving a different combination of five interventions. We had not anticipated this design in our protocol and chose to analyse it separately from other trials, considering comparisons where the only difference between groups was the intervention of interest and then pooling those separate comparisons.

Unit of analysis issues

All trials were randomized by individual, and outcome data were reported for participants.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the available data on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before obtaining pooled estimates of relative effects, we carried out a statistical heterogeneity analysis assessing the value of the I2 statistic, thereby estimating the percentage of total variance across studies that was due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Higgins 2002). We considered a value greater than 30% as a sign of important heterogeneity, and if present we sought an obvious explanation for the heterogeneity by considering the design of the trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

We recorded the number of included studies that reported each outcome but did not use any statistical techniques to try to identify the presence of publication bias. We planned that if we identified more than 10 studies for a comparison we would generate a funnel plot and analyse it by visual inspection.

Data synthesis

We used DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects model meta‐analyses of risk ratios (RR) in RevMan 5.2 for dichotomous data and weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data. Any pooled estimates had a 95% CI.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We considered subgroups based on patient demographics (older people > 80 years, pregnant women, ASA score), duration of anaesthesia, type and urgency of surgery, and variations in the definition of an outcome. However, there was not enough evidence to investigate these subgroups in a robust way.

We were unable to identify a consistent explanation for statistical heterogeneity in the trial results.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis according to the methodological study quality (including only trials with low risk of bias) but did not complete this due to a lack of variation in the risk of bias in the studies.

Summary of findings tables

There are two summary of findings tables, one for each main comparison in the review (Table 1; Table 2). The requirement for these tables was introduced during the development of this review and the methods were not in place in the protocol. Therefore, the selection of which outcomes to present in the table occurred after seeing the results.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

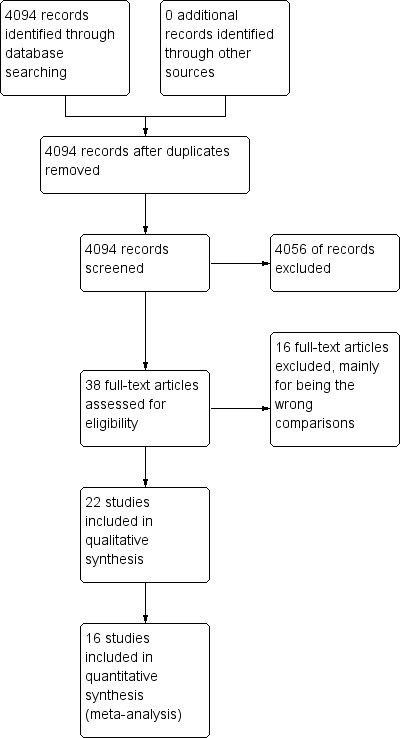

The search for this review was carried out as part of a single search for three related reviews on the prevention and treatment of perioperative hypothermia. Figure 1 summarizes the search results, combined for searches conducted in June 2011, June 2012, February 2013, November 2013 and February 2014. These searches identified a total of 4094 hits. For this review we retrieved 38 papers for consideration and included 22. This is summarized in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We tried to contact authors of three studies (Biddle 1985; Hindsholm 1992; Lenhardt 1997) to clarify details but were either unable to contact them or they were not able to provide further information. For one of these (Lenhardt 1997) we obtained clarification from a third party.

Included studies

We included 22 studies (Characteristics of included studies) either comparing thermal insulation with control or with active warming. For six of these (Bernard 1987; Biddle 1985; Brauer 2000; Estebe 1996; Hindsholm 1992; Hoyt 1993) the temperature data could not be used within the quantitative analysis plan we had decided on either because of incomplete reporting, different choice of time points or presentation of summary statistics other than means and standard deviations. The results from these studies were considered qualitatively. Four trials reported measuring 'aural', 'aural canal' or 'ear' temperature (Bennett 1994; Berti 1997; Hindsholm 1992; Ng 2003) and it was not clear whether this meant tympanic temperature or temperature measured by infrared aural canal measurement, which is known to be less reliable.

One trial (Shao 2012) had a complex design with 32 treatment groups each receiving some combination of five different interventions. From this, we pooled results where thermal insulation was the only difference, or where the only difference was thermal insulation compared to forced air warming.

For one trial (Erickson 1991) we pooled two different groups with different amounts of insulation.

The included studies were in patients undergoing a variety of different surgical operations, some with regional and some with general anaesthesia. Overall a good range of elective surgical situations was covered. A major issue was that there was a wide range of co‐interventions used in the studies, such as warmed fluids and inspired gases, and a range of types of thermal insulation used both in the active and control groups.

The commonest type of thermal insulation was some form of reflective blanket compared to either standard care (typically sheets or cotton blankets) or active warming (most commonly forced air warming).

The range of outcomes reported was disappointingly narrow. Temperature was commonly reported but at a variety of time points and in a number of different ways. Bleeding and shivering were uncommonly reported, and in some cases we were not able to use the data. Shivering was not clearly defined. There were no data on several of our secondary outcomes: infections and wound complications, pressure ulcers, minor cardiovascular complications, or unplanned high dependency or intensive care admission. No adverse effects of the interventions were reported.

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 studies (Excluded studies) largely because the comparison was not included in the review on reading the full text.

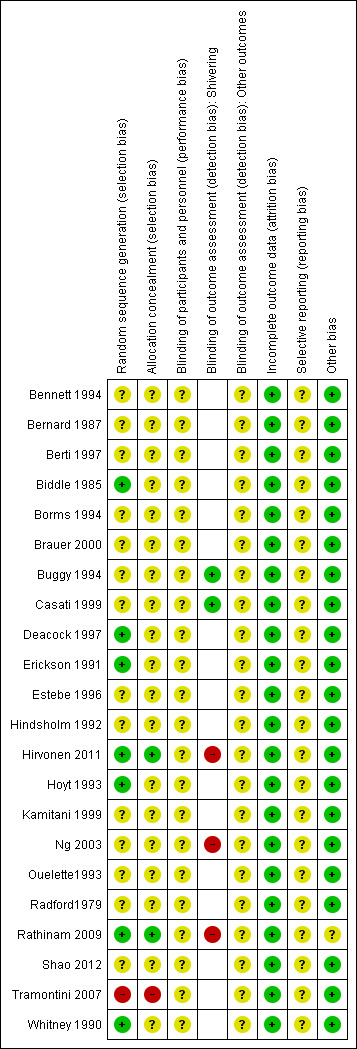

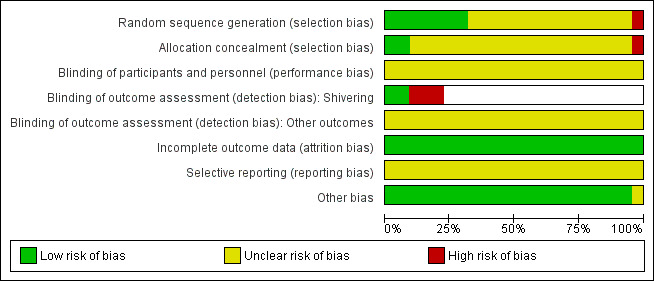

Risk of bias in included studies

Summaries of the judgements for risk of bias are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Note that for the outcome shivering many trials did not report this outcome but we have coded the risk of bias as unclear. Details of included studies are in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Reporting of allocation concealment was largely unclear making it difficult to come to an overall view of the likelihood of selection bias. There were no obvious imbalances in the groups in tables of demographic data, but this does not rule out selection bias.

Blinding

It is difficult to blind patients (particularly under regional analgesia only) and clinicians to the intervention used and this may influence the use of other interventions or the recording of temperature.

For shivering, where this was recorded by an observer blinded to allocation we reported the risk of bias as low.

In general, there was a high risk of bias due to lack of blinding across trials, but the direction of effect this would cause is unclear.

Studies where blinding was not reported appear as a blank in the risk of bias table for the assessment of blinding for shivering.

Incomplete outcome data

The trials were of fairly short duration in a highly controlled environment and so attrition did not occur to any serious extent. The risk of bias due to attrition was therefore low.

Selective reporting

We found no definite evidence of selective reporting, but we did not seek out trial protocols. Few of the outcomes we hoped to find were reported, but we were unclear whether they were collected.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other definite sources of potential bias.

Effects of interventions

Additional insulation versus control

Core temperature

Most trials reported core temperature at a variety of sites (tympanic, nasopharyngeal, oesophageal), at different time points (number of minutes after induction, incision or some other event), with some as tables and some as graphs, and with a variety of summary statistics presented. We decided to summarise data by presenting WMD at 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after induction and at the end of surgery or on admission to post‐anaesthetic care. This meant we were unable to include data from several trials: Bernard 1987 reported temperature at 45 minutes after skin incision with a comparison involving 14 patients that suggested a benefit of reflective blankets, Brauer 2000 reported medians and ranges with a higher median temperature with reflective blankets in a comparison involving 18 patients, Estebe 1996 reported at time points after inflation of a limb tourniquet that occurred at a varying time after induction of anaesthesia suggesting a benefit of reflective blankets in a comparison with 20 patients, Hindsholm 1992 did not report the numbers of patients in each group, and Hoyt 1993 reported temperature at 10 and 70 minutes post‐induction in 30 patients without showing a clear effect. Biddle 1985 reported means with a P value from analysis of variance with little difference between the means. These data seemed consistent with the quantitative meta‐analysis.

Within Shao 2012 there were 16 comparisons where the only difference was the use of body wraps, with a variety of co‐interventions. We did not want to pool all these comparisons simply by calculating pooled means and standard deviations for all patients with and without body wraps as this would have mixed up the comparisons. However, entering 16 different comparisons in a meta‐analysis would assume they were all independent trials and give excessive weight to this trial. We have therefore presented the results from Shao as a subgroup with 16 separate trials but not pooled it with the other trials.

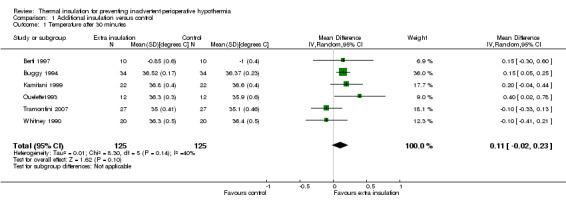

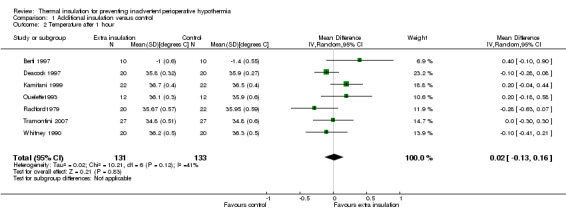

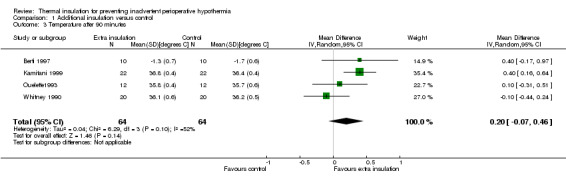

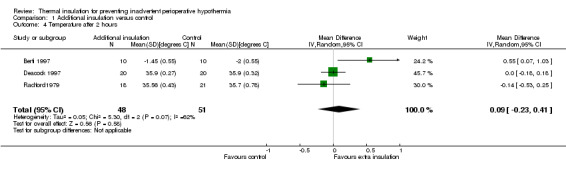

There were between three and seven studies contributing to analyses at each of the time points, with between 99 and 513 participants. At 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes there was a small difference in temperature in favour of added insulation (Analysis 1.1; Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4) but this was not statistically significant. There was a moderate degree of heterogeneity, with I2 ranging from 40% to 62% in the meta‐analyses, but none of the pre‐specified subgroup analyses were possible and there was no obvious single explanation for the heterogeneity. Despite the heterogeneity we have chosen to present a meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model analysis to present an estimate of the average effect across a range of clinical situations.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 1 Temperature after 30 minutes.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 2 Temperature after 1 hour.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 3 Temperature after 90 minutes.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 4 Temperature after 2 hours.

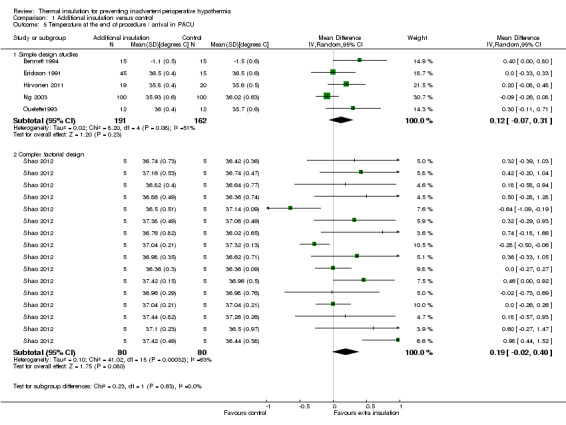

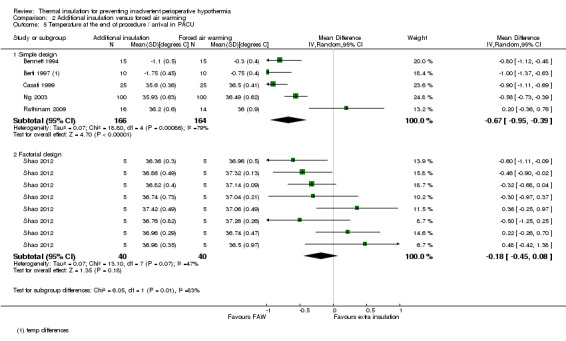

At the end of surgery (Analysis 1.5) the estimated average temperature difference was 0.12 ºC (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.31) higher in the extra insulation group in the simple design trials and 0.19 ºC (95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.40) in the pooled analysis of the 16 comparisons within Shao 2012.. Even at the higher end of the CI this effect is small and of unclear clinical importance.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 5 Temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU.

Cardiovascular outcomes

There were no data on our other primary outcome of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

There were few data on estimated blood loss and length of stay in post‐anaesthetic care, resulting in very uncertain estimates (Analysis 1.6; Analysis 1.8).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 6 Estimated blood loss.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 8 Length of stay in PACU.

Two trials contributed 268 participants to an analysis of the risk of shivering with a pooled RR of 0.36 (95% CI 0.12 to 1.06), showing an unclear effect (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Additional insulation versus control, Outcome 7 Shivering.

Extra insulation versus active warming

Core temperature

There were between three and six studies contributing between 90 and 410 participants to the analyses of temperature at various time points. All the additional insulation was by the use of a reflective blanket or unspecified body wraps.

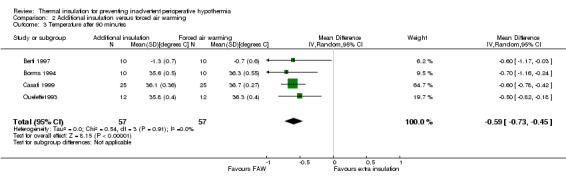

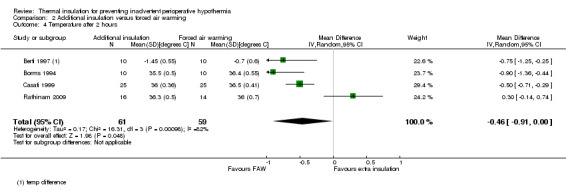

There seemed to be a consistent, although not always statistically significant, result of a small temperature difference in favour of forced air warming at all time points, with point estimates ranging from ‐0.15 ºC (95% CI ‐0.31 to 0.01) at 30 minutes (Analysis 2.1) to ‐0.59 ºC (95% CI ‐0.73 to ‐0.45) at 90 minutes (Analysis 2.3). There was important heterogeneity in the comparisons at 120 minutes (I2 = 82%; Analysis 2.4) and end of surgery (I2 = 79% among the trials with simple design; Analysis 2.5). This seemed to be particularly due to the result from Rathinam 2009, which gave a point estimate in favour of reflective insulation. A possible explanation for this was that in this trial the reflective blankets were applied preoperatively whereas the forced air warming was only applied intraoperatively; this is however a hypothesis. Removing the data of Rathinam 2009 at 120 minutes and the end of surgery reduced the I2 to 29% and 64% respectively but did not alter the finding of a small effect in favour of forced air warming, with a difference of ‐0.64 ºC with added insulation (95% CI ‐0.89 to ‐0.39) at 120 minutes and ‐0.79 ºC (95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.58) at the end of surgery. The pooled result within the Shao trial was not statistically significant.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 1 Temperature after 30 minutes.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 3 Temperature after 90 minutes.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 4 Temperature after 2 hours.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 5 Temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU.

Despite the heterogeneity we chose to pool the results to give an idea of the overall effect as the absolute differences in temperature between trials were small.

Cardiovascular outcomes

There were no data on our other primary outcome of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

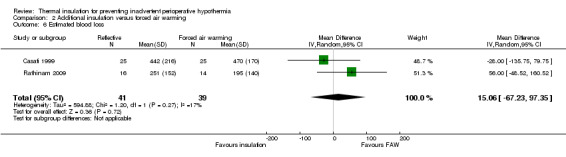

There were no clear effects on estimated blood loss (Analysis 2.6), risk of shivering (Analysis 2.7) or length of stay in post‐anaesthetic care (Analysis 2.8) with wide CIs and skewed data.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 6 Estimated blood loss.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 7 Shivering.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 8 Length of stay in PACU.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found no clear evidence of an effect of added thermal insulation on core temperature during surgery. Forced air warming seems to result in a higher core temperature of about 0.5 ºC to 1 ºC compared to added insulation (largely reflective blankets in these studies). It is unclear how important this is in preventing adverse outcomes associated with unintended perioperative hypothermia as it is unclear how many extra patients would avoid important hypothermia with forced air warming. There was insufficient evidence to provide clear results about any other outcomes we had intended to address, and interpretation of the temperature difference would need to rely on modelling the consequences of this temperature difference, which was beyond the remit of our review. Results are summarised in the summary of findings tables (Table 1; Table 2).

The degree of variation between the studies in the patients, anaesthetic techniques and particularly the presence of co‐interventions may explain some of the variation in outcomes between studies. We might expect that there would be a ceiling effect of applying several interventions intended to avoid perioperative hypothermia and so studies with several co‐interventions may fail to find a big difference for the particular comparison of interest.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We were not able to collect data on the risk of hypothermia as we had intended, and our analysis plan was chosen after seeing what data we managed to collect. Even with a strategy aimed at maximizing use of the available data, there were several trials that we could not use, and there was very limited reporting of outcomes other than temperature. It is not clear that selective reporting of outcomes, if present, would favour forced air warming or insulation. We might expect the effect of added insulation to be exaggerated compared to no intervention but we did not find an effect.

The patient populations were fairly representative of people undergoing a range of elective surgical procedures with a range of anaesthetic techniques and co‐interventions aimed at heat conservation. The evidence does, therefore, seem directly applicable to current practice.

Quality of the evidence

Reporting of trial design was largely incomplete, with difficulty interpreting the risk of bias. It would be difficult to blind patients and practitioners to the intervention used but it is not clear how great an effect that may have on temperature readings made by healthcare professionals. Attrition was generally low, as would be expected in short term studies.

There was moderate inconsistency between studies, although the actual size of difference in temperature was generally small. For some outcomes there were few data, which resulted in great uncertainty in the effect estimate.

Potential biases in the review process

Several decisions about the handling of the data and investigation of heterogeneity were made after seeing the data, which may introduce bias. We have therefore been cautious about the interpretation of the data.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The NICE guideline recommended the use of forced air warming rather than added insulation for intraoperative use (NICE 2008) and our findings do not contradict that. The guideline was based on modelling of the effect of temperature differences on patient‐important outcomes and an economic analysis, and we have not attempted to replicate that.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Among the options examined in this review, forced air warming seems to maintain core temperature better than reflective blankets, although the implications of this for patients and health services are unclear from the trial results. However, we did not find evidence to contradict the findings of the NICE guideline.

Implications for research.

Any further trials in this area should be conducted to a high quality and collect outcome data that easily translate into important patient relevant outcomes. As there are several other competing interventions, design of further trials should be based on an overview of all relevant comparisons. This review raised a specific hypothesis about whether preoperative application of reflective blankets is as effective as intraoperative forced air warming.

Acknowledgements

This review builds on the work undertaken as part of the NICE clinical guideline on inadvertent perioperative hypothermia and we would like to acknowledge the group's work. Michael Lowe helped with some sifting of trial results.

We would like to thank Anna Lee (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), Oliver Kimberger, Janneke Horn, Rainer Lenhardt (peer reviewers) and Anne Lyddiatt (consumer) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this protocol for the systematic review.

We would like to thank Anna Lee (content editor), Cathal Walsh (Statistical editor), Oliver Kimberger, Dan Sessler (peer reviewers) and Robert Wyllie (consumer referee) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library

#1 MeSH descriptor Rewarming explode all trees #2 (intervention* adj3 treat*):ti,ab or vasodilatat* or infrared light* or intravenous nutrient* or warming system* or ((Mattress* or blanket*) near (warm water or Electric)) or (warm* near (air or CO2 or fluid* or an?esthetic* or IV or gas* or device* or patient* or passive* or active* or skin or surg*)) or (warming or blanket*):ti,ab or pharmacological agent* or thermal insulat* or pre?warm* or re?warm* #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 MeSH descriptor Hypothermia explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor Body Temperature Regulation explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Shivering explode all trees #7 hypo?therm* or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver* or ((thermal or temperature) near (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)) or (low* near temperature*) or thermo?genesis or ((reduc* or prevent*) and temperature and (decrease or decline)) or (heat near (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)) or (core near (thermal or temperature*)) #8 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 (#3 AND #8)

Run November 2013 to update the search and add the text word cover* to search #2 "((Mattress* or blanket* or cover*) near (warm water or Electric))" & " (warming or blanket* or cover*):ti,ab"

Appendix 2. Search strategy for MEDLINE (OvidSP)

1. Rewarming/ or (intervention* adj3 treat*).ti,ab. or vasodilatat*.mp. or infrared light*.mp. or intravenous nutrient*.mp. or warming system*.mp. or ((Mattress* or blanket*) adj3 (warm water or Electric)).mp. or (warm* adj3 (air or CO2 or fluid* or an?esthetic* or IV or gas* or device* or patient* or passive* or active* or skin or surg*)).mp. or (warming or blanket*).ti,ab. or pharmacological agent*.mp. or thermal insulat*.mp. or (pre?warm* or re?warm*).mp. 2. exp Hypothermia/ or exp body temperature regulation/ or exp piloerection/ or exp shivering/ or hypo?therm*.af. or normo?therm*.mp. or thermo?regulat*.mp. or shiver*.mp. or ((thermal or temperature) adj2 (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)).mp. or (low* adj2 temperature*).mp. or thermo?genesis.mp. or ((reduc* or prevent*).af. and (temperature adj3 (decrease or decline)).mp.) or (heat adj2 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)).mp. or (core adj2 (thermal or temperature*)).mp. 3. 1 and 2 4. ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 5. 3 and 4

Rerun November 2013 with the addition of textword cover* at end of search #1 "or cover*.mp"

Appendix 3. Search strategy for EMBASE (OvidSP)

1. warming/ or (intervention* adj3 treat*).ti,ab. or vasodilatat*.mp. or infrared light*.mp. or intravenous nutrient*.mp. or warming system*.mp. or ((Mattress* or blanket*) adj3 (warm water or Electric)).mp. or (warm* adj3 (air or CO2 or fluid* or an?esthetic* or IV or gas* or device* or patient* or passive* or active* or skin or surg*)).mp. or (warming or blanket*).ti,ab. or pharmacological agent*.mp. or thermal insulat*.mp. or (pre?warm* or re?warm*).mp. 2. exp HYPOTHERMIA/ or exp thermoregulation/ or reflex/ or exp SHIVERING/ or hypo?therm*.af. or normo?therm*.mp. or thermo?regulat*.mp. or shiver*.mp. or ((thermal or temperature) adj2 (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)).mp. or (low* adj2 temperature*).mp. or thermo?genesis.mp. or ((reduc* or prevent*).af. and (temperature adj3 (decrease or decline)).mp.) or (heat adj2 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)).mp. or (core adj2 (thermal or temperature*)).mp. 3. 1 and 2 4. (placebo.sh. or controlled study.ab. or random*.ti,ab. or trial*.ti,ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 5. 3 and 4

Rerun November 2013 with the addition of textword cover* at end of search #1 "or cover*.mp"

Appendix 4. Search strategy for ISI Web of Science

#1 TS=((hypo?therm* or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver*) or ((thermal or temperature) SAME (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)) or (low* SAME temperature*) or thermo?genesis or ((reduc* or prevent*) and temperature and (decrease or decline)) or (heat SAME (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance)) or (core SAME (thermal or temperature*))) #2 TS=((intervention* SAME treat*) or (vasodilatat* or infrared light* or intravenous nutrient* or warming system*) or ((Mattress* or blanket*) SAME (warm water or Electric)) or (warm* and (air or CO2 or fluid* or an?esthetic* or IV or gas* or device* or patient* or passive* or active* or skin or surg*))) or TI=(warming or blanket*) or TI=(pharmacological agent* or thermal insulat* or pre?warm* or re?warm*) #3 #1 and #2 #4 TS=(random* or (trial* SAME (control* or clinical*)) or placebo* or multicenter* or prospective* or ((blind* or mask*) SAME (single or double or triple or treble))) #5 #3 and #4

Rerun November 2013 with the addition of the title word cover* to search #2 "TI=(warming or blanket* or cover*)"

Appendix 5. Search strategy for CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

S1 (MM "Warming Techniques") S2 vasodilatat* or infrared light* or intravenous nutrient* or warming system* S3 intervention* N3 treat* S4 ((Mattress* or blanket*) and (warm water or Electric)) S5 (warm* and (air or CO2 or fluid* or an?esthetic* or IV or gas* or device* or patient* or passive* or active* or skin or surg*)) S6 AB warming or blanket* S7 AB pharmacological agent* S8 TI thermal insulat* or AB (pre?warm* or re?warm*) S9 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 S10 (MM "Hypothermia") OR (MM "Body Temperature Regulation") OR (MM "Shivering") S11 hypo?therm* or normo?therm* or thermo?regulat* or shiver* S12 AB ((thermal or temperature) and (regulat* or manage* or maintain*)) S13 low* N3 temperature* S14 ( reduc* or prevent* ) and temperature and ( decrease or decline ) S15 thermogenesis S16 heat N3 (preserv* or loss or retention or retain* or balance) S17 core N3 (thermal or temperature*) S18 S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 S19 S9 and S18

Rerun November 2013 with the addition of the textword cover* to search S6 "AB warming or blanket* or cover*"

Appendix 6. Data extraction form

| Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group Study Selection, Quality Assessment & Data Extraction Form Thermal insulation for preventing inadvertent perioperative hypothermia |

Code of Paper: |

|

| Reviewer initials: | Date: | |

| First author | Journal/Conference Proceedings etc | Year |

|

|

Study eligibility

| RCT/Quasi/CCT (delete as appropriate) | Relevant participants | Relevant interventions | Relevant outcomes |

| Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No / Unclear |

Yes / No* / Unclear |

* Issue relates to selective reporting – when authors may have taken measurements for particular outcomes, but not reported these within the paper(s). Reviewers should contact trialists for information on possible non‐reported outcomes & reasons for exclusion from publication. Study should be listed in ‘Studies awaiting assessment’ until clarified. If no clarification is received after three attempts, study should then be excluded.

| Do not proceed if any of the above answers are ‘No’. If study to be included in ‘Excluded studies’ section of the review, record below the information to be inserted into ‘Table of excluded studies’. |

| |

|

Freehand space for comments on study design and treatment: |

Methodological quality

| Allocation of intervention | ||

| State here method used to generate allocation and reasons for grading (quote) | Grade (circle) | |

| Page No | Adequate (Random) | |

| Inadequate (e.g. alternate) | ||

| Unclear | ||

|

Concealment of allocation Process used to prevent foreknowledge of group assignment in a RCT, which should be seen as distinct from blinding | ||

| State here method used to conceal allocation and reasons for grading (quote) | Grade (circle) | |

| Page No | Adequate | |

| Inadequate | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Blinding | Page No. | |

| Person responsible for participants care | Yes / No | |

| Participant | Yes / No | |

| Outcome assessor | Yes / No | |

| Other (please specify) | Yes / No | |

|

Intention‐to‐treat An intention‐to‐treat analysis is one in which all the participants in a trial are analysed according to the intervention to which they were allocated, whether they received it or not. | ||

| Number participants entering trial | ||

| Number excluded | ||

| % excluded (more or less than 15%) | ||

| Not analysed as ‘intention‐to‐treat’ | ||

| Unclear | ||

| Were withdrawals described? | Yes / No / Not clear | |

| Free text: | ||

Participants and trial characteristics

| Participant characteristics | ||

| Further details | Page No. | |

| Age (mean, median, range, etc) | ||

| Sex of participants (numbers / %, etc) | ||

| Trial characteristics | ||

| Further details | Page No. | |

| Single centre / multicentre | ||

| Country / Countries | ||

| How was participant eligibility defined? | ||

| How many people were randomized? | ||

| How many people were analysed? | ||

| Control group (size and details e.g. 2 cotton blankets + fluid warmer + HME) | ||

| Intervention group 1 (size and details) | ||

| Intervention group 2 (size and details) | ||

| Intervention group 3 (size and details) | ||

| Time treatment applied (e.g. 30 min pre‐op) | ||

| Duration of treatment (mean +SD) | ||

| Total anaesthetic time | ||

| Duration of follow up | ||

| Time‐points when measurements were taken during the study | ||

| Time‐points reported in the study | ||

| Time‐points you are using in RevMan | ||

| Trial design (e.g. parallel / cross‐over*) | ||

| Other | ||

* If cross‐over design, please refer to the Cochrane Editorial Office for further advice on how to analyse these data

| Relevant outcomes | ||

| Reported in paper (circle) | Page No. | |

| Infection and complications of surgical wound | Yes / No | |

| Major CVS complications (CVS death, MI, CVA) | Yes / No | |

| Risk of hypothermia (core temp) | Yes / No | |

| Pressure ulcers | Yes / No | |

| Bleeding complications | Yes / No | |

| Other CVS complications (arrhythmias, hypotension) | Yes / No | |

| Patient reported outcomes (shivering, discomfort) | Yes / No | |

| All cause mortality | Yes / No | |

| Adverse effects | Yes / No | |

| Relevant subgroups | Page No. | |

| Age >80 | Yes / No | |

| Pregnancy | Yes / No | |

| ASA scores | Yes / No | |

| Urgency | Yes / No | |

Subgroups

Number of participants

| Age >80 | Pregnant | Elective | Urgent | ASA 1 or 2 | ASA 3 or 4 | |

| Control | ||||||

| Intervention 1 | ||||||

| Intervention 2 | ||||||

| Intervention 3 | ||||||

| | ||||||

| Free text: | ||||||

| For Continuous data | ||||||||||||||||

| Code of paper |

Outcomes |

Unit of measurement |

Control group | Intervention 1 (thermal insulation) | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | ||||||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Temperature at end of surgery | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Temperature at ................. | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Temperature at ................. | Degrees C | |||||||||||||||

| Number of units red cells transfused | Units | |||||||||||||||

| For dichotomous data (n = no of participants) | ||||||||||||||||

| Code of paper |

Outcomes |

Control group | Intervention 1(thermal insulation) | Intervention 2 | Intervention 3 | Free Text | ||||||||||

| n | n | n | n | |||||||||||||

| Wound complications | ||||||||||||||||

| Major CVS complications (CVS death, non‐fatal MI, non‐fatal CVA and non‐fatal arrest) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bleeding complications (coagulopathy) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pressure Ulcers | ||||||||||||||||

| Other CVS complications (hypotension, bradycardia, hypotension) | ||||||||||||||||

|

Other information which you feel is relevant to the results Indicate if: any data were obtained from the primary author; if results were estimated from graphs etc; or calculated by you using a formula (this should be stated and the formula given). In general if results not reported in paper(s) are obtained this should be made clear here to be cited in review. |

|

|

| Freehand space for writing actions such as contact with study authors and changes |

References to trial

Check other references identified in searches. If there are further references to this trial link the papers now & list below. All references to a trial should be linked under one Study ID in RevMan.

| Code each paper | Author(s) | Journal/Conference Proceedings etc | Year |

References to other trials

| Did this report include any references to published reports of potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? | ||

| First author | Journal / Conference | Year of publication |

| Did this report include any references to unpublished data from potentially eligible trials not already identified for this review? If yes, give list contact name and details | ||

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Additional insulation versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Temperature after 30 minutes | 6 | 250 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [‐0.02, 0.23] |

| 2 Temperature after 1 hour | 7 | 264 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.02 [‐0.13, 0.16] |

| 3 Temperature after 90 minutes | 4 | 128 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [‐0.07, 0.46] |

| 4 Temperature after 2 hours | 3 | 99 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [‐0.23, 0.41] |

| 5 Temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Simple design studies | 5 | 353 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.12 [‐0.07, 0.31] |

| 5.2 Complex factorial design | 1 | 160 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [‐0.02, 0.40] |

| 6 Estimated blood loss | 2 | 84 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐27.80 [‐175.48, 119.87] |

| 7 Shivering | 2 | 268 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.12, 1.06] |

| 8 Length of stay in PACU | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Additional insulation versus forced air warming.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Temperature after 30 minutes | 3 | 90 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.31, 0.01] |

| 2 Temperature after 1 hour | 4 | 114 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.24 [‐0.38, ‐0.10] |

| 3 Temperature after 90 minutes | 4 | 114 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.59 [‐0.73, ‐0.45] |

| 4 Temperature after 2 hours | 4 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.46 [‐0.91, ‐0.00] |

| 5 Temperature at the end of procedure / arrival in PACU | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Simple design | 5 | 330 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.67 [‐0.95, ‐0.39] |

| 5.2 Factorial design | 1 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.18 [‐0.45, 0.08] |

| 6 Estimated blood loss | 2 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 15.06 [‐67.23, 97.35] |

| 7 Shivering | 3 | 280 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.48, 18.69] |

| 8 Length of stay in PACU | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Additional insulation versus forced air warming, Outcome 2 Temperature after 1 hour.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bennett 1994.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, UK | |

| Participants | Patients undergoing elective hip arthroplasty. Age range 54 to 89, mean 73, 30 male, 15 female Exclusions: grossly obese, malnourished, endocrine abnormalities, pyrexia |

|

| Interventions | 1) No intraoperative warming 2) reflective insulation (Thermolite) 3) forced air warming |

|

| Outcomes | Aural canal temperature at end of procedure, transfusion as dichotomous data and mean (SD) transfusion in those transfused | |

| Notes | All: IV crystalloid infusion at ambient temp (19‐21 ºC), blood warmed to 37 ºC | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Allocated randomly" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Allocated randomly" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Bernard 1987.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, France | |

| Participants | 28 patients undergoing elective total hip replacement under 'controlled hypotension'. Mean age 64 years | |

| Interventions | 1) reflective blanket in before leaving pre‐anaesthesia room 2) heating humidifier of inhaled gases from start of controlled ventilation 3) combination of 1) and 2) 4) no hypothermia prevention |

|

| Outcomes | Pulmonary artery temperature before admission to operating room, on skin incision, and 45 minutes after incision | |

| Notes | All: ambient temperature IV fluids Data not included in analysis as time point did not fit |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "according to a randomization table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "according to a randomization table", which created 4 equal groups of 7 patients |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Berti 1997.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, USA | |

| Participants | 30 ASA 1 and 2 patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty under general anaesthesia with epidural Exclusion criteria: obesity, on drugs likely to affect heat balance, thyroid disease, dysautonomia, Raynaud's syndrome |

|

| Interventions | 1) control with no blankets 2) reflective blankets 3) forced air warming |

|

| Outcomes | Aural temperature at baseline on arrival into operating theatre, after induction then at 30, 60, 90, 120 min, and at the end of surgery | |

| Notes | All low flow anaesthesia with heat and moisture exchanger. IV fluids at room temperature | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "according to a randomization table" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "according to a randomization table", which produced three groups of 10 patients |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Biddle 1985.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, USA | |

| Participants | People aged 65 to 90 undergoing abdominal surgery for more than 75 minutes No exclusion criteria listed |

|

| Interventions | 1) No head covering, standard drapes (n=43) 2) Paper surgical hat, standard drapes (n=42) 3) Plastic head cover after induction, standard drapes (n=42) |

|

| Outcomes | Nasopharyngeal temperature at 10 and 60‐70 minutes after induction | |

| Notes | No other warming interventions described. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "assigned randomly using a table of random numbers" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "assigned randomly using a table of random numbers" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | None described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Borms 1994.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, Belgium | |

| Participants | 20 ASA 1 and 2 patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty under general anaesthesia. Age range 55 to 75, mean age approx 68, 5 male, 15 female Exclusions: infections, fever, diabetes, thyroid disease |

|

| Interventions | 1) Reflective drapes 2) Forced air warming |

|

| Outcomes | Oesophageal temperature after induction and then at 15 minute intervals | |

| Notes | Semiclosed circle system with heat and moisture exchanger IV fluids warmed to 37 ºC |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Brauer 2000.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, Germany | |

| Participants | 36 patients undergoing major urological intra‐abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | 1) Warmed IV fluids plus cotton drapes 2) Warmed IV fluids plus reflective blankets 3) Warmed IV fluids plus upper body convective air warming 4) Warmed IV fluids plus reflective blankets plus convective air warming |

|

| Outcomes | Tympanic temperature at 2 hours after start of surgery | |

| Notes | Median and range only reported, so data not analysed in review | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "randomly assigned" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Buggy 1994.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, Republic of Ireland | |

| Participants | 68 ASA 1 and 2 patients undergoing elective orthopaedic and plastic surgery on the limbs under general anaesthesia. Exclusion criteria: under 14 years or over 80 years, pyrexia, requirement for intraoperative blood transfusion, operations over 80 mins duration, requiring mechanical ventilation |

|

| Interventions | 1) standard surgical drapes 2) reflective blanket plus standard surgical drapes |

|

| Outcomes | Nasopharyngeal temperature at 15, 30 and 45 minutes after induction Incidence of shivering, recorded by recovery room nurses and defined as 'readily detectable fasciculations and tremor of the jaw, neck, trunk and extremities lasting longer than 20 s' Patient reported feeling of being cold on visual analogue score |

|

| Notes | No IV fluids given | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "allocated randomly" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "allocated randomly" |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | None reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Shivering | Low risk | Assessed by nurse blinded to allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Other outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No loss to follow up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No clear evidence |

| Other bias | Low risk | None expected |

Casati 1999.

| Methods | Single centre RCT, Italy | |

| Participants | 50 ASA 1 to 3 patients undergoing elective total hip arthroplasty under spinal/epidural. Average age about 67 years, sex not mentioned Exclusion criteria: severe cardiovascular and respiratory disease, obesity, thyroid disease, dysautonomia, Raynaud's syndrome |

|

| Interventions | 1) Reflective blankets 2) Forced air warming |

|

| Outcomes | Bladder temperature at 30 min, 60 min, 90 min, 120 min, at end of procedure Length of stay in PACU Estimated blood loss Observed shivering, definition not given |

|

| Notes | IV fluids and blood heated to 37 ºC | |