Abstract

HCC is globally recognized as a major health threat. Despite significant progress in the development of treatment strategies for liver cancer, recurrence, metastasis, and drug resistance remain key factors leading to a poor prognosis for the majority of liver cancer patients. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop effective biomarkers and therapeutic targets for HCC. Collagen, the most abundant and diverse protein in the tumor microenvironment, is highly expressed in various solid tumors and plays a crucial role in the initiation and progression of tumors. Recent studies have shown that abnormal expression of collagen in the tumor microenvironment is closely related to the occurrence, development, invasion, metastasis, drug resistance, and treatment of liver cancer, making it a potential therapeutic target and a possible diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for HCC. This article provides a comprehensive review of the structure, classification, and origin of collagen, as well as its role in the progression and treatment of HCC and its potential clinical value, offering new insights into the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis assessment of liver cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer ranks as the sixth most prevalent malignant tumor globally and is the third most common cause of mortality attributed to malignant tumors.1 Primary liver cancer predominantly consists of HCC (75%–85%) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (10%–15%).1 Recent studies indicate that the development of liver cancer is linked to various causes, such as viral hepatitis, obesity, alcohol consumption, and NAFLD. During the progression of these conditions, most patients are likely to develop liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which is characterized primarily by the structural disruption of liver lobules and the extensive accumulation of abnormal collagen.2,3 Currently, surgery remains the primary treatment for early-stage liver cancer. However, a significant number of patients are diagnosed with liver cancer after the optimal window for surgery has passed.4 Targeted drugs, including sorafenib and lenvatinib, have been shown to extend the overall survival of individuals with liver cancer by approximately 3 months; however, the efficacy of this treatment is considered suboptimal.5,6 Therefore, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has sanctioned the combined administration of the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) atezolizumab (anti-Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)), bevacizumab (anti-VEGF), duvalizumab (anti-PD-L1), and tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for the treatment of advanced unresectable or metastatic HCC.7,8 Compared to sorafenib, atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab extended the overall survival of patients with liver cancer by 6 months, while the combination of durvalumab with tremelimumab resulted in a 2.5-month extension of overall survival. These findings demonstrated a significant improvement in the prognosis of patients with liver cancer.9,10,11 Nevertheless, considering the practical aspects of clinical application, the primary challenges hindering the improvement of patient prognosis are resistance to both targeted drugs and immunotherapy, and the precise biological mechanisms underlying this resistance remain elusive.

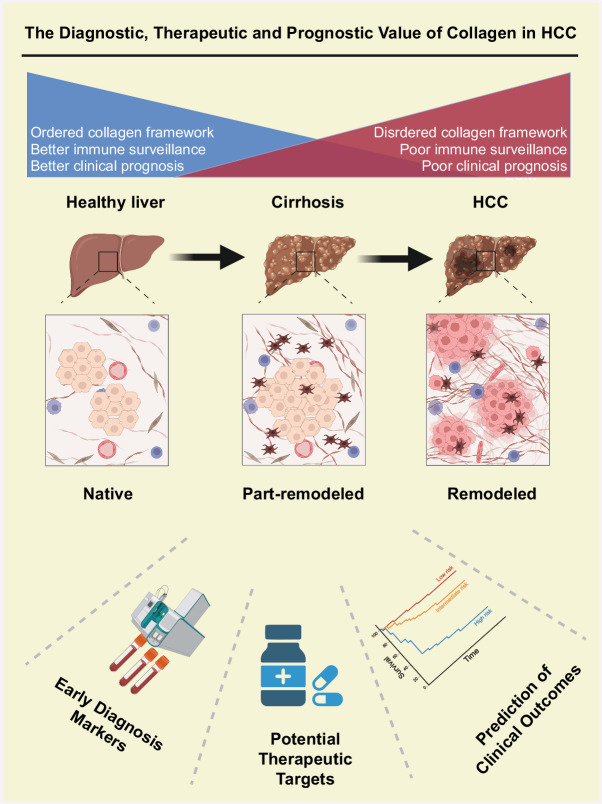

According to the “soil and seed” theory, tumor cells (seeds) can proliferate only when they are situated in a conducive microenvironment (soil).12 Consequently, the inteplay between the tumor microenvironment and tumor cells has emerged as a prominent area of research and is currently experiencing significant growth. Conventional cancer treatment approaches are increasingly targeting the tumor microenvironment.13 The tumor microenvironment consists of cancer cells in conjunction with various components, including immune cells, endothelial cells, fibrocytes, and the extracellular matrix (ECM).13 Studies have indicated that targeting the tumor stroma can significantly influence tumor progression. The ECM plays a crucial role in the tumor microenvironment, significantly impacting tumorigenesis and the progression of tumors.14,15,16 Collagen, which is the most prevalent component of the ECM, represents a substantial component of animal connective tissue and is the most prevalent and widely distributed functional protein in mammals.16,17 Many studies indicate that collagen contributes to the progression of cancer and exhibits notably upregulated expression in diverse human tumor tissues, including renal clear cell carcinoma, HCC, lung adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma tissues, with elevated levels of collagen typically correlating with a poorer clinical prognosis.18 Nonetheless, another study suggested that the collagen synthesized by cancer-associated fibroblasts might have a protective function in the progression of cancer, suggesting that collagen might play unexpectedly complex roles in the biological processes associated with carcinoma.19 Collagen also plays an important role in the occurrence and development of liver cancer. Liver cancer cells interact with surrounding collagen, and this interaction promotes the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells. The presence of collagen is also associated with drug resistance in liver cancer. Studies have shown that after liver cancer cells interact with collagen, cellular signaling pathways are altered, leading to the development of resistance to targeted drugs. This article provides an overview of the characteristics of collagen, including its structure, type, and sources, as well as its role in reshaping the tumor microenvironment and its potential clinical significance as a therapeutic target (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic value of collagen in HCC.

GENERAL STRUCTURE AND CLASSIFICATION OF COLLAGEN

To date, more than 28 distinct types of collagen have been identified.20 Although the structures of different collagen proteins display notable differences, they also share common characteristics, with most proteins typically displaying a double-helix structure but collagen proteins consisting of 3 α-peptide chains organized in a right-handed helical conformation.21 The collagen domain is a helical region consisting of 3 strands, with each of the 3 polypeptide chains ranging arranged in a left-handed orientation, contributing to a left-handed helical structure. Through interactions among amino acid residues, these chains align along a common axis and intertwine via hydrogen bonds, leading to a sturdy, right-handed superhelical structure.16

According to its function, collagen can be divided into fibrillar collagen and nonfibrillar collagen.16 Nonfibrillar collagen is composed of a variety of components, including fibronectin fibrils, reticular collagen, beaded filament collagen, anchoring collagen, and transmembrane collagen proteins.22 Fibrillar collagens, which are distinguished by their elongated and unbroken triple helix conformation, include collagen Ⅰ, II, III, V, XI, XXIV, and XXVII. Collagen I is the primary protein in the collagen family and accounts for 90% of all collagen proteins in humans, providing essential support and acting as a foundational structure for connective tissues such as the skin, tendons, bones, ligaments, and cornea; collagen I may also be involved in the regulation of both tumors and embryos23 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

The types, molecular weights, and tissue distribution of collagen22

| Type | Molecular weight (kDa) | Tissue distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Fibril-forming collagen | ||

| I | 95 | Skin, tendons, bones, ligaments, corneas, tumors, embryos |

| II | 95 | Hyaline cartilage, vitreous, embryonic cornea, neural retina |

| III | 95 | Skin, lung, liver, intestine, vascular system |

| V | 120–145 | Forming scaffold for type I collagen fibers |

| XI | 110–145 | Cartilage, vitreous body |

| XXIV | — | Coexisting with type I and type V collagens |

| XXVII | — | Cartilage of adult organisms |

| Nonfibril-forming collagen | ||

| Reticular collagen | ||

| IV | 170–180 | Basement membrane |

| Beaded filament collagen | ||

| VI | 140 | Skeletal muscle, lung, blood vessels, cornea, tendon, skin, cartilage, intervertebral disk, fat |

| Anchoring collagen | ||

| VII | 170 | Skin, dermal-epidermal junctions, oral mucosa, cervix, |

| Reticular collagen | ||

| VIII | 61 | Endothelial cells, Descemet membrane |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| IX | 68–115 | Cartilage, vitreous humor, cornea |

| Reticular collagen | ||

| X | 59 | Hypertrophic cartilage |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XII | 220, 340 | Skin, tendon, cartilage |

| Transmembrane collagen | ||

| XIII | 62–67 | Endothelial cells, epidermis, |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XIV | 220 | Skin, tendon, cornea, cartilage |

| Endostatin-associated collagen | ||

| XV | 125 | Basement membrane regions of microvessels, cardiac muscle, or skeletal muscle cells |

| fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XVI | 150–160 | Skin, cartilage, heart, intestine, arterial wall, kidney |

| Transmembrane collagen | ||

| XVII | 180 | Skin, mucosa, eyes |

| Endostatin-associated collagen | ||

| XVIII | 200 | Liver, eyes, kidneys |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XIX | 165 | Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XX | 185, 170, 135 | Cornea, blood vessels |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XXI | — | heart, placenta, stomach, jejunum, skeletal muscle, kidney, lung, pancreas, lymph node |

| Fibril-associated collagen | ||

| XXII | 200 | Heart, skeletal muscle |

| Transmembrane collagen | ||

| XXIII | — | Lung, cornea, skin, tendon, amnion |

| Transmembrane collagen | ||

| XXV | 50, 100 | Brain, heart, testis, eyes |

THE BIOSYNTHESIS AND DEGRADATION OF COLLAGEN

The transcriptional activity of collagen is predominantly regulated by various types of cells, growth factors, and cytokines, and fibroblasts are the primary cells responsible for synthesizing collagen.22,24 The mRNA encoding collagen undergoes translation in the rough endoplasmic reticulum to produce procollagen molecules.22 After translation, these procollagen molecules undergo a series of complex modifications, such as hydroxylation of proline and lysine, stabilization of the triple helical structure, and glycosylation of C-terminal propeptides. Hydroxylation plays a crucial role in maintaining the thermal stability and structural integrity of collagen fibers, whereas glycosylation provides a binding site for carbohydrates. These alterations are essential for the correct folding of collagen and the development of a triple helix structure. Following processing and collagen prepeptide assembly, the triple helix molecules are enclosed in secretory vesicles located within the Golgi apparatus and subsequently released into the extracellular space. Following this, the procollagen trimer undergoes further processing according to the collagen type. Specific proteases cleave the carbon and nitrogen in the propeptide as part of the regulatory mechanisms involved in collagen synthesis. In the extracellular space, the process of collagen fibril assembly is intricate and involves self-assembly and intermolecular interactions between collagen monomers. The propeptide of the procollagen molecules influences the formation of fibrils, which can subsequently be aligned according to the tissue type. Furthermore, the stability of fibrils is augmented via the establishment of covalent cross-links, which are generated by lysine and hydroxylysine residues within the terminal peptide. These cross-linking reactions improve the physical and mechanical characteristics of collagen fibrils and create networks.22,25

The degradation pathway of collagen is divided into intracellular pathway and extracellular pathway. At present, only a few proteases, such as cysteine protease cathepsin K and the members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family, have been found to have the ability to degrade collagen.26 These proteases can be synthesized and secreted into the intercellular substance by many cells.27 Five pathways are considered for the degradation of collagen: (1) several types of cells can internalize collagen through phagocytosis, which is mediated by the adhesion interaction between α1β2 integrins. Subsequently, the internalized collagen is transported to lysosomes and degraded by cathepsin;28 (2) MMP in ECM can effectively degrade collagen in intercellular space;29 (3) The initial cleavage of collagenous fibrils produces large collagen fragments, which enter cells through uPARAP/Endo180-mediated endocytosis;30 (4) Collagen fragments can also enter cells for degradation through the action of giant pinocytosis;31 (5) The membrane from endoplasmic reticulum wraps the collagen fragment in cytoplasm and become autophagosomes, which is then fused with lysosomes, and the collagen fragment is degraded by cysteine protease.32

THE ROLE OF COLLAGEN IN CANCER

Collagen functions as the predominant structural component of the ECM and has diverse functions in the majority of cancers,33 such as facilitating tumor proliferation, metastasis, and resistance to therapeutic agents while also hindering tumor progression. In particular, collagen can facilitate tumor progression by providing structural support for tissues and might have a novel function in preserving the anchoring and morphology of cancer cells, potentially facilitating their proliferation.34 Changes in collagen I (α1,3) within the tumor microenvironment, particularly changes in neoplastic collagen properties such as density, orientation, length, and cross-linking, have the potential to enhance tumor invasion and metastasis.35,36 In addition, as fundamental elements of the ECM, collagen fibers perform dual functions. They provide structural integrity and support to various cell types in tumor tissues, and they also modulate cellular activities through signal transduction via interactions with cell surface receptors, including integrins, the discoidin domain receptor 1 (DDR1) and discoidin domain receptor (DDR2), osteoclast-associated receptor, glycoprotein VI, G6b-B, leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1), and the mannose family receptor uPARAP/Endo180;25 these interactions have the potential to directly influence cancer cell metabolism, proliferation, and malignant progression.25

On the other hand, collagen can also inhibit tumor progression. A lack of collagen I has been identified as a factor that can result in upregulated expression of the chemokine CXCL5 in cancer cells via SOX9. Elevated levels of CXCL5 subsequently facilitate the recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which consequently impede the antitumor immune response. Blocking chemokine signal transduction has the potential to reverse the antitumor immune characteristics induced by the elimination of collagen I and decelerate the progression of pancreatic cancer.19 In particular, during tumor progression, cancer-associated fibroblasts accumulate within the tumor, produce excess ECM, and actively compress cancer cells using the contractile properties of actin to form a capsule that encapsulates the cancer cells. This capsule acts as a barrier to restrict tumor growth and leads to the build-up of intratumoral pressure, which in turn leads to altered localization of the transcriptional regulator Yes-associated protein in tumor cells and reduced proliferation.37 Another study demonstrated that the degradation of collagen I by MPP hinders the discoidin structural DDR1-NF-κBp62-Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) signaling pathway to impede pancreatic tumorigenesis in wild-type mice, suggesting that individuals with pancreatic cancer who exhibit elevated levels of collagen I may have longer median survival.38

THE ROLE AND MODIFICATION OF COLLAGEN IN HCC

In general, the main role of collagen in HCC is to remodel the tumor microenvironment and promote tumor growth, metastasis, and drug resistance while also influencing tumor progression and prognosis. Understanding the role of collagen in the treatment and prevention of HCC is crucial.

The important role of collagen in remodeling of the tumor microenvironment in HCC

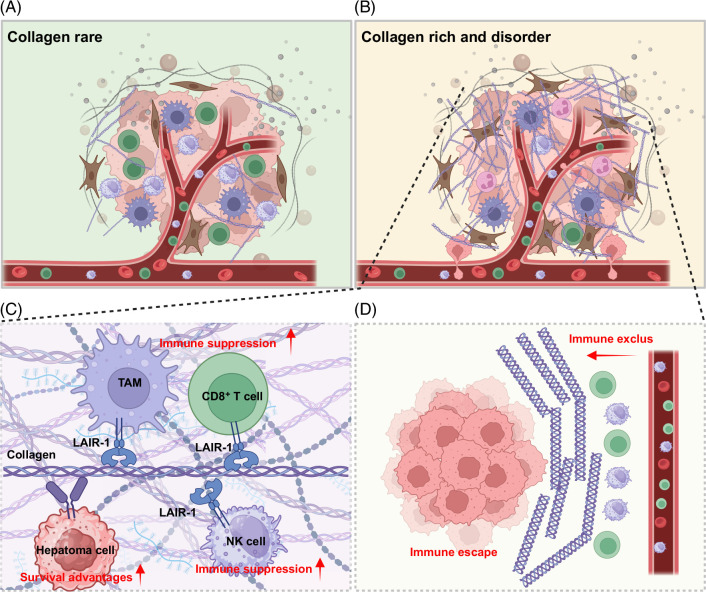

Immune surveillance within the liver microenvironment plays a crucial role as a barrier to the onset and progression of liver cancer.13 However, cancer cells frequently manage to evade immune system surveillance by employing a range of mechanisms, ultimately resulting in tumor cell survival and tumor formation. A diminished capacity to identify tumor antigens, an accumulation of immunosuppressive cells (such as neutrophils, regulatory T cells, regulatory B cells, myeloid suppressor cells, M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophages, etc.), and increased expression of coinhibitory lymphocyte signals, including immune checkpoint ligands and receptors, collectively establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment in the context of liver cancer.39 Collagen is the predominant protein found in the HCC microenvironment and plays a critical role in the structure of the tumor microenvironment40 (Figure 2). It is capable of modulating the immune microenvironment through a series of ligand–receptor inteactions, resembling a “lock and key” mechanism.41,42,43,44 These receptors include LAIR-1, the mannose family receptor uPARAP/Endo180, the discoid domain receptors DDR1 and DDR2, integrin, osteoclast-associated receptor, glycoprotein VI, and G6b-B (which are involved in collagen architecture and signaling orchestration). For example, LAIR-1 is expressed at high levels in diverse immune cell types, including T cells, B cells, NK cells, macrophages, and monocytes. The interaction between collagen and LAIR-1 results in the development of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by remodeling the biological function of the above immune cell types.45 The expression of DDR1, another important collagen receptor with tyrosine kinase activity, is significantly increased in HCC. The activation of the collagen I-DDR1 pathway has the potential to enhance the stemness of tumor cells and exacerbate the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment, consequently facilitating cancer progression and treatment resistance.46 Furthermore, activation of the collagen XV-DDR1 pathway has been identified as a crucial mechanism mediating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and suppressing the metastatic potential of HCC.47 Within the liver cancer microenvironment, tumor-associated macrophages are pivotal in promoting tumor progression because they suppress tumor-infiltrating T-cell function and induce T-cell depletion, a well-known phenomenon that represents a significant challenge in cancer immunotherapy. During the process of tumor progression, the ECM undergoes degradation and is then replaced by tumor-specific collagen, which can induce macrophages to acquire an immunosuppressive phenotype. This process reduces the recruitment of cytotoxic T cells and inhibits T-cell proliferation, thereby diminishing the efficacy of immunotherapy in treating HCC.48 Furthermore, densely packed collagen structures can serve as a physical impediment, hindering the intratumoral infiltration of NK cells and CD8+ T cells to create an “immune desert” environment, leading to unfavorable tumor progression and diminished effectiveness of immunotherapy.49 In conclusion, aberrant accumulation of collagen within the tumor microenvironment can influence the efficacy of immune checkpoints in the context of liver cancer through 2 distinct mechanisms. First, interactions with receptors in the tumor microenvironment can attenuate the antitumor effects of immune cells on the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and increase the survival of tumor cells. Second, collagen can establish a compact physical barrier that obstructs the penetration of immune cells and the localized dispersion of targeted therapeutics.

FIGURE 2.

The role of collagen in remodeling of the immune microenvironment. (A) The tumor microenvironment contains few fibroblasts and a small amount of secreted collagen, with normal infiltration of immune cells; in contrast, (B) shows a tumor microenvironment with a significant number of activated fibroblasts that secrete large amounts of collagen in a disorganized manner, resulting in a deficiency of immune cells within the tumor and thereby facilitating tumor vascular invasion and metastasis; (C) demonstrates that collagen induces immunosuppression in immune cells through receptor interactions and enhances the survival capabilities of tumor cells; (D) shows that the dense arrangement of collagen fibers surrounding the tumor obstructs the infiltration of immune cells such as CD8+ T cells and NK cells, leading to immune evasion. Abbreviations: LAIR-1, leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1; NK cell, natural killer cell; TAM, tumor-associated macrophages.

The collagen-rich HCC microenvironment also leads to enhanced mechanotransduction.40 In the HCC microenvironment, cells are exposed to a variety of physical forces, including tensile, compressive, shear, and static mechanical forces, where cells convert mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals that lead to changes in cellular behavior.50 In the context of the collagen-rich HCC microenvironment, the collagen-rich ECM is typically stiffer than normal liver tissue. Studies have shown that in the cirrhotic and/or fibrotic stage, liver stiffness increases dramatically from 1–2 kPa to 5–6 kPa. In HCC, the stiffness of tumor-infiltrated liver can exceed 20 kPa.51 Increased stiffness can activate mechanosensitive ion channels and integrins on the cell surface, leading to the transmission of mechanical signals into the cell.40 For example, it can activate focal adhesion kinase (FAK), the proto-oncogene protein tyrosine kinase selective catalytic reduction, the Ras homolog family member, and the Yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif mechanosensory apparatus in cancer-associated fibroblasts.52,53 The increased mechanical force also induces integrin activation and the formation of complexes of actin-binding proteins and signaling molecules [eg, FAK, selective catalytic reduction (Src), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase] at the cell membrane, which in turn leads to increased dedifferentiation, proliferation, adhesion, and migration of liver cancer cells.40 Understanding the mechanisms by which the collagen-rich HCC microenvironment influences mechanotransduction is critical for the development of targeted therapies that can disrupt these processes and potentially inhibit tumor progression.

Collagen promotes the proliferation, cellular stemness, and metastatic capability of hepatoma cells

Collagen may contribute to the malignant behavior of HCC cells by promoting malignant behaviors such as proliferation, stemness, and metastatic tendency. Targeting these pathways and processes may provide therapeutic strategies to inhibit HCC cell proliferation and improve patient prognosis.

COL1A1

Elevated expression of COL1A1, which encodes the principal component of collagen I, is associated with decreased survival rates and increased malignancy in patients with HCC. Inhibition of COL1A1 expression using siRNA technology impedes various functions of HCC cells; additionally, collagen I can upregulate SOX2, OCT4, and CD133 expression levels through the Slug-dependent EMT process, serving as a marker for HCC stem cells.54 In the context of cancer cell stemness, elevated levels of collagen I are correlated with unfavorable prognosis among patients with HCC. The poor prognosis of patients with HCC might be attributed to the interaction between collagen I and DDR1, which can interact with CD44 to enhance DDR1 signaling and counteract Hippo signaling by promoting the recruitment of the protein phosphatase 2A to MST1, resulting in the hyperactivation of Yes-associated protein and the enhancement of cancer cell stemness.46

COL4A1

COL4A1 is the most significantly overexpressed collagen gene in HCC, and the upregulation of COL4A1 in HCC, which is driven by RUNX1, enhances the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells via the FAK-Src signaling pathway, rendering cells with elevated COL4A1 expression responsive to FAK or Src inhibitor treatment.55

COL15A1

COL15A1 encodes the alpha chain of collagen XV, a member of the fibril-associated collagens with interrupted triple helices collagen family, which has antiangiogenic and antitumor properties and plays a crucial role in liver tissue homeostasis. In HBV-associated HCC, COL15A1 can interact with P4HB, which promotes HepG2.2.15 cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and growth.56 Moreover, collagen XV has the ability to modulate EMT through regulation of the DDR1 snail/slug axis, thereby functioning as a metastasis inhibitor in HCC.47

Src homology and collagen homolog 3

Src homology and collagen homolog 3 (Shc3) is a protein that belongs to the Shc family of adaptor proteins; the members of this family are involved in signal transduction and contain several protein-protein interaction domains, such as Src homology 2 and collagen homology 1 domains, which allow them to interact with various signaling molecules and transduce signals within the cell. Shc3 is upregulated in HCC as a result of DNA demethylation in its upstream promoter region, is under the control of c-Jun, and interacts with major vault protein, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase to boost extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation independently of the conventional Shc1, Grb2, SOS, Ras, and Raf pathways. The Shc3 signaling pathway triggers a cascade of downstream tumorigenic responses, such as proliferation, migration, invasion, and EMT, and significantly contributes to sorafenib resistance in HCC57 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The function and mechanism of collagen in liver cancer

| Type | Expression in HCC | Function | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL1A1 | Up | Promotion | COL1A1 upregulation → Enhanced AClonogenicity, motility, Invasiveness, and tumorsphere formation → promotion of slug-dependent EMT → upregulation of stemness markers (SOX2, OCT4, CD133) → enhanced HCC stemness and metastasis54 |

| Collagen I upregulation → DDR1 activation → CD44 interaction → Hippo signaling inhibition → YAP activation → Enhanced HCC Cell stemness → pomotion of HCC progression and therapeutic resistance46 | |||

| COL4A1 | Up | Promotion | RUNX1 upregulation → COL4A1 upregulation → FAK-Src signaling activation → promotion of the growth and metastasis of HCC cells55 |

| COL15A1 | Up | Inhibition | Collagen XV upregulation → DDR1 downregulation → Snail/slug inhibition → EMT → inhibition of cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis in HCC47 |

| Promotion | HBV infection → COL15A1 upregulation → interaction with P4HB → inhibition of GRP76 → promotion of HepG2.2.15 cell growth and malignancy56 | ||

| Shc3 | Up | Promotion | Shc3 upregulation → demethylation of Shc3 promoter → c-Jun binding → Shc3 expression → interaction with MVP → MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 activation → EMT → HCC cell-proliferation and metastasis → positive feedback loop with c-Jun phosphorylation → role in sorafinib resistance57 |

Abbreviations: DDR1, discoidin domain receptor 1; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MVP, major vault protein; Shc3, Src homology and collagen homolog 3; YAP, Yes-associated protein.

The physical characteristics of collagen play a role in the progression of HCC

Recent studies have suggested that the physical characteristics of collagen, including the alignment, orientation, and cleavage or integrity of collagen fibers, are important for the regulation of tumors. The orientation of collagen fibers has the potential to influence the invasion and migration of tumor cells.58 The interaction between DDR1 and collagen enhances collagen fiber alignment, impedes immune cell infiltration, and facilitates tumor growth.59 Remarkably, MMP-cleaved Col I and intact Col I have contrasting effects on tumor progression and metastasis. Activation of the DDR1-NF-κB-p62-nrf2 signal transduction pathway facilitates the proliferation of pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells. Conversely, inhibition of DDR1 by intact Col I leads to its degradation and suppresses the growth of pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Patients exhibiting elevated levels of matrixmetalloproteinase-cleaved Col I, DDR1, and Nrf2 had a greater median survival rate than patients with tumors characterized by abundant intact Col I expression and reduced levels of DDR1 and Nrf2.38 These other carcinoma studies provide insights into HCC; previous studies have shown that liver tissue from mice resistant to collagenase I developed more severe fibrosis and grew fewer smaller tumors, but the treatment of mice with degraded collagen fragments resulted in the development of more larger tumors in the liver. This suggests that cleaved collagen I may also promote the development of HCC.60 Hence, therapy targeting MMPs could inhibit the synthesis of cleaved collagen I, thereby impeding the process of collagen restructuring during tumor progression and exerting an antitumor effect. Moreover, the density and tightly packed arrangement of collagen within tumors can significantly impact the local drug concentration. The compact collagen structure in tumors serves as a physical barrier, impeding the infiltration and dispersion of therapeutic agents within the tumor tissue, which leads to reduced drug efficacy and the development of treatment resistance. Therefore, understanding the density of collagen in tumors is crucial for designing effective drug delivery strategies.61

Collagen remodeling and HCC

Collagen remodeling is a process in which the structure, arrangement, and content of collagen fibers are altered during pathological processes such as tissue injury, repair, or tumor.62 In HCC, collagen remodeling plays a significant role and affects tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis:

Increased collagen production: In the early stages, liver injury leads to fibrosis, where the liver’s wound-healing response results in excessive collagen synthesis, primarily by myofibroblasts.63 The increased collagen deposition forms scar tissue that disrupts normal liver architecture.

Matrix remodeling: As fibrosis progresses, the ECM undergoes extensive remodeling. Typically, collagen types I and III are overproduced, resulting in stiff and less permeable tissue, which impairs nutrient and waste exchange and creates a microenvironment that favors cancer cell growth.

Abnormal collagen cross-linking: Excessive collagen cross-linking can lead to increased stability and decreased degradation, further contributing to ECM stiffness.64 This can also affect the function of cells within the liver, such as hepatocytes and immune cells, which may contribute to tumor development.

Altered collagen turnover: Dysregulation of collagen degradation enzymes, such as MPP, can imbalance the degradation process, allowing collagen to accumulate and a profibrotic environment to persist.65

Modified collagen glycosylation: Alterations in the glycosylation patterns of collagen, such as abnormal addition or truncation of glycan moieties, can affect the stability, structure, and function of collagen molecules.66 These changes may result from dysregulation of glycosyltransferases, glycosidases, or sugar nucleotide transporters in HCC cells.

Interaction of collagen with growth factors and ECM components: Collagen can modulate the activity of growth factors such as TGF-β and PDGF, which are known to promote fibrosis and contribute to cancer progression.67 Collagen also interacts with other ECM proteins, such as fibronectin, laminin, and elastin, to form a complex network that provides structural support for HCC. For example, proteoglycans, which are complex glycoproteins consisting of a core protein and one or more covalently attached glycosaminoglycan chains, interact with collagen.68 These interactions can influence collagen organization and contribute to the development of a protumorigenic microenvironment.

In addition, excessive collagen deposition results in a denser and more rigid matrix; abnormal collagen cross-linking renders the ECM less flexible, more resistant to degradation, and more disorganized. These changes contribute to ECM stiffness, which not only creates a physical barrier that hinders drug delivery and immune cell infiltration but also promotes cell survival, proliferation, migration, and invasion, as well as drug resistance. Understanding the mechanisms of collagen remodeling in HCC may provide valuable insights into the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for the management of HCC (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Collagen remodeling and HCC

| Mechanism | Factor/pathway | Effect on collagen/ECM | Consequence on HCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increase or reduce collagen production | HBx→HIF/lysyl oxidase (LOX) Pathway | Triggers production of ECM components. | Promotes HCC development69 |

| NF-κB/P4HA2 pathway and LMCD1-AS1/let-7g/P4HA2 pathway increase P4HA2 expression. | Abnormal accumulation of collagen | Promote cancer cell proliferation and metastasis.70 | |

| Matrix remodeling | Accumulation of AGEs in ECM caused by type 2 diabetes and AGEs promote changes in collagen structure. | Enhance the viscoelasticity of the ECM, increase viscosity dissipation and accelerate stress relaxation. | Promotes HCC induction by altering ECM properties.71 |

| Abnormal collagen cross-linking | Voltage-gated calcium channel α2δ1 subunit-positive tumor-initiating cells (TICs) from HCC specifically secrete LOX. | LOX leads to the cross-linking of collagen, forming a stiff ECM. | Drive the formation of TICs with a stiff mechanical trait.64 |

| Altered collagen turnover | Dysregulation of collagen degradation enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases, can imbalance the degradation process. | Collagen accumulation sustains a profibrotic environment. | Associated with poor patient outcomes.65 |

| Interaction of collagen with growth factors and ECM components | Collagen can modulate the activity of growth factors such as TGF-β and PDGF | Growth factors can regulate the composition of ECM. | Promote fibrosis and contribute to cancer progression.67 |

Abbreviations: AGE, advanced glycation end-products; AS1, antisense RNA 1; ECM, extracellular matrix; HBx, HBV X protein; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; LOX, lysyl oxidase; TIC, tumor-initiating cells.

THE CLINICAL VALUE OF COLLAGEN IN HCC

Given that collagen can reshape the immune microenvironment, affect the efficacy of targeted therapy and immunotherapy for liver cancer, promote tumor cell proliferation, stemness, and metastasis potential, and exhibit abnormal expression in tumor cells, collagen may have significant potential value as a biomarker and therapeutic target for liver cancer.

Collagen can serve as a biomarker for early detection and prognostic evaluation of liver cancer

In clinical practice, the availability of biomarkers with adequate diagnostic performance for early HCC is limited. This has prompted the exploration and utilization of alternative biomarkers for early screening and diagnosis in asymptomatic patients. The development of HCC from fibrosis and cirrhosis is indeed a complex process involving significant changes in ECM, particularly collagen. Collagen is the most abundant protein in connective tissue and plays a critical role in tissue structure and stability. Several aspects of collagen changes are involved in the progression from fibrosis to cirrhosis and ultimately to HCC. Biomarkers derived from these changes in collagen metabolism, such as collagen secretion, modification, and interactions, may potentially be used in the early detection of HCC. For example, noninvasive tests such as elastography, which measures tissue stiffness, may reflect increased collagen content.72 In addition, circulating collagen fragments or specific collagen-related proteins in blood or urine could serve as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers. A recent study integrated collagen III with MMP 1 to establish an HCC-ABC diagnostic assay, which exhibited performance comparable to that of other previous diagnostic biomarkers and underscored the significant potential of collagen III in the early detection of HCC.60 However, it’s important to note that research in this area is ongoing, and these biomarkers need to be validated in clinical settings before they can be widely used in clinical practice. To develop these biomarkers for early detection, researchers would need to validate their specificity and sensitivity in large patient cohorts, correlate them with disease stage, and assess their performance in combination with other diagnostic methods such as imaging, serum markers, or molecular profiling. Early-stage biomarkers could significantly improve HCC detection rates and treatment outcomes.

Furthermore, collagen and its homologs play a crucial role in predicting the prognosis of patients with liver cancer. A study investigating the prognostic significance of tumor stromal collagen in HCC using a quantitative assessment technique based on second harmonic generation revealed a significant association of increased collagen cross-linking, density, and aggregation with adverse outcomes in terms of overall survival, histological grade, and tumor recurrence.73 In addition, Huang et al74 conducted a 20-year cohort study to investigate the value of the collagen-specific area for predicting clinical outcomes in patients with HCC, and the study revealed that collagen-specific area stage was significantly and independently correlated with liver-related mortality. In addition, abnormal collagen expression in HCC tissues, eg, COL IV, COL4A2, and COL24A1, usually indicates an unfavorable prognosis. The abovementioned types of collagen generally indicate a poor prognosis for patients; however, there are specific types of collagen proteins that are associated with a favorable prognosis. Yao et al47 reported that the survival rate and recurrence-free survival time of patients with HCC who had high Col15a1 expression were superior to those of patients with low expression levels (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Collagen can serve as a prognosis biomarker for liver cancer

| Collagen | Relative | Function |

|---|---|---|

| COL I | Prognosis (−) | Collagen I induces DDR1 activation and leads to poor prognosis.46 |

| COL Ⅳ | Prognosis (−) | Preoperative evaluation of collagen Ⅳ level can be used to evaluate the liver function and prognosis of patients with HCC after hepatectomy.75 |

| COL4A1/2 | Prognosis (−) | High level of COL4A2 gene expression were associated with reduced progression-free survival of patients with HCC.76 |

| CTHRC1 | Prognosis (−) | The upregulation of CTHRC1 has been shown to accelerate the progression of liver cancer.77,78 |

| COL24A1 | Prognosis (−) | High levels of COL24A1 expression level have been associated with an unfavorable prognosis.79 |

| SHC4 | Prognosis (−) | Upregulation of SHC4 expression is associated with poor prognosis.80 |

| COL15A1 | Prognosis ( + ) | The survival rate and recurrence-free survival time of HCC patients with high COL15A1 expression were better than those with low COL15A1 expression.47 |

(+) represents positive correlation.

(−) represents negative correlation.

Abbreviations: DDR1, discoidin domain receptor 1; SHC, Src homology and collagen homolog.

The feasibility of collagen as a therapeutic target for HCC

To date, some combinations of anti-PD-L1/Programmed death 1 therapy and antiangiogenic drugs, such as the combination of atilizumab with bevacizumab, have been approved as primary treatments for individuals diagnosed with liver cancer. Furthermore, the combination of nabulizumab, which targets Programmed death 1, and Keytruda has also been shown to be effective in HCC control.11,81 However, in the clinical setting, the efficacy of these medications is suboptimal because a significant number of patients develop drug resistance. Furthermore, biomarkers that can be used to guide the use of ICIs are lacking. Accumulating evidence has shown that the reduced responsiveness of HCC to ICIs and the variability of treatment outcomes can be primarily attributed to the abnormal accumulation of collagen, and various forms of collagen can serve as potential targets for augmenting the efficacy of immunotherapy.82 Mechanistically, collagen-targeted therapy can augment the intratumoral infiltration of T cells, thereby improving the effectiveness of ICIs. Furthermore, certain drugs, such as cetuximab, have the ability to withstand collagen and can exert a sustained antitumor effect on collagen-rich tumors, leading to notable therapeutic efficacy.83 The affinity modification of collagen for anti-cytokine antibodies is also important because it can lead to improved effectiveness and longevity of anti-inflammatory antibodies.84

Considering the “hepatitis-cirrhosis-liver cancer” trilogy in liver cancer, some traditional drugs, such as renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, aspirin, and metformin, have been shown to inhibit collagen deposition in the tumor microenvironment, which is believed to influence collagen remodeling, promote the infiltration of CD8+ T cells, and enhance the effectiveness of Programmed death 1/PD-L1 inhibitors. This evidence supports new applications of available drugs in liver cancer immunotherapy, with the potential for rapid clinical translation.70,85,86

Moreover, biological processes related to collagen secretion, modification, interaction, and collagen degradation, such as endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy, may become potential targets for liver cancer treatment.87 Targeting the mechanisms that regulate collagen secretion, such as inhibiting the synthesis or transport of collagen molecules, could potentially reduce the tumor-promoting effects of the ECM in liver cancer. As discussed above, altered collagen glycosylation can significantly affect the structure and function of the ECM in HCC. Targeting the enzymes involved in collagen modification, such as glycosyltransferases, glycosidases, or sugar nucleotide transporters, may help to restore normal collagen glycosylation patterns and attenuate the tumor-promoting effects of modified collagen in HCC. In conclusion, understanding and targeting the biological processes associated with collagen in HCC may offer promising opportunities for the development of novel therapeutic interventions and inhibit HCC progression (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets from collagen remolding

| Process | Description | Implications for HCC diagnosis or treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Collagen secretion | Dysregulation leads to accumulation of aberrant collagen structures, contributing to a tumor-permissive microenvironment. | Targeting collagen secretion mechanisms (eg, inhibiting synthesis or transport) may reduce tumor-promoting effects of ECM.70,82,88,89 |

| Collagen modification | Altered glycosylation impacts structure and function of ECM in HCC. | Targeting enzymes involved in collagen modification (eg, glycosyltransferases, glycosidases) could restore normal collagen glycosylation and attenuate tumor-promoting effects.66,90 |

| Collagen interaction | Understanding molecular interactions between collagen and cell surface receptors (eg, integrins, DDRs) can identify therapeutic targets. | Targeting these receptors or modulating their signaling pathways may disrupt tumor-promoting cell-ECM cross talk.46,91 |

| Collagen degradation | Dysregulation contributes to ECM remodeling and tumor progression. | Targeting enzymes responsible for collagen degradation (eg, MMPs) may prevent excessive ECM remodeling and inhibit tumor cell invasion and metastasis.36 |

Abbreviations: DDR, discoidin domain receptor; ECM, extracellular matrix; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinase.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Historically, collagen was primarily considered to be a structural component connecting cells. Recent studies have shown that collagen remodeling plays a significant role in the initiation and progression of cancer. Collagen can influence tumor cell proliferation and metabolic processes. Additionally, it may alter the immune microenvironment, leading to the development of an “immune desert.” Targeting collagen has significant potential for cancer treatment. Although several key receptors that interact with collagen have been identified, the details of collagen signal transduction in the tumor microenvironment of HCC remain unclear. Due to the diversity and complex effects of collagen in liver cancer, its mechanisms of action are not yet fully understood. This limits the development of targeted and effective treatment strategies targeting collagen.

Although collagen plays an important role in the remodeling process of the HCC microenvironment, suggesting that targeting collagen may improve immunotherapy resistance in patients with HCC, the underlying mechanisms of collagen-induced resistance to immunotherapy are not well understood, and the key targets identified to date are sparse and some are still inspired by studies in other tumor types. Given the heterogeneity of tumors, these targets may have a limited role in liver cancer immunotherapy. In addition, these targets are still in the research phase, and more studies are needed to determine their efficacy and indications in HCC immunotherapy. With a deeper understanding of the liver cancer microenvironment and the role of collagen in HCC immunotherapy, we may discover more potential therapeutic targets and mechanisms.

Therefore, in-depth research on the mechanisms of collagen in liver cancer, revealing its key regulatory mechanisms, can aid in the development of more effective treatment strategies and improve treatment outcomes and survival rates for liver cancer patients.

Further research is needed to investigate the physical properties of collagen, such as its orientation and cleavage status, and their impact on the tumor microenvironment. However, when studying the specific characteristics of collagen in liver cancer and its differences from collagen in normal tissues, there are indeed some challenges and limitations: (1) A lack of suitable in vivo models: Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of liver cancer, appropriate in vivo models are needed to simulate the characteristics of collagen in liver cancer, and there is currently a lack of ideal in vivo models that fully replicate the characteristics of liver cancer, which limits the in-depth study of collagen characteristics in liver cancer. (2) Technological limitations: To accurately compare the characteristics of collagen in liver cancer and normal tissues, high-resolution imaging techniques, molecular biology techniques, and other methods are needed. (3) Complexity of the tumor microenvironment: The characteristics of collagen in liver cancer may be influenced by various factors, such as cytokines and the ECM. To address these challenges, there is an urgent need to establish more realistic in vivo models and integrate a variety of technical approaches, including single-cell sequencing and polarized light imaging, which will facilitate comprehensive investigations of the characteristics of collagen in liver cancer, shedding light on its connection to the onset and progression of the disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dong-yang Ding: writing—review and editing, resources, investigation. Shu-ya Jiang: resources; Yun-xi Zu and Yuan Yang: resources and revision. Xiao-jie Gan: supervision. Sheng-xianYuan: supervision, funding acquisition, and conceptualization. Wei-ping Zhou: supervision and conceptualization. All authors have been involved in the writing of the manuscript at draft and any revision stages and have read and approved the final version.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (82273349).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DDR1, discoidin domain receptor 1; DDR2, discoidin domain receptor; ECM, extracellular matrix; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; ICIs, Immune checkpoint inhibitors; LAIR-1, leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PD-L1, Programmed death-ligand 1; Shc3, Src homology and collagen homolog 3; Src, selective catalytic reduction.

Dong-yang Ding, Shu-ya Jiang, Yun-xi Zu, and Yuan Yang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Dong-yang Ding, Email: d1906172531@163.com.

Shu-ya Jiang, Email: syjiang2018@163.com.

Yun-xi Zu, Email: 1228975119@qq.com.

Yuan Yang, Email: yangyuan.ehbh@gmail.com.

Xiao-jie Gan, Email: 852495907@qq.com.

Sheng-xian Yuan, Email: yuanshengx@126.com.

Wei-ping Zhou, Email: ehphwp@126.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toh MR, Wong EYT, Wong SH, Ng AWT, Loo LH, Chow PKH, et al. Global epidemiology and genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:766–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, Mohseni A, Kamel IR, Cloyd JM, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. JAMA Surg. 2023;158:410–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yang C, Zhang H, Zhang L, Zhu AX, Bernards R, Qin W, et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:203–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Association For The Study Of The Liver,European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dopazo C, Søreide K, Rangelova E, Mieog S, Carrion-Alvarez L, Diaz-Nieto R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2024;50:107313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rimassa L, Finn RS, Sangro B. Combination immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023;79:506–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, Chan SL, Kelley RK, Furuse J, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2100070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casak SJ, Donoghue M, Fashoyin-Aje L, Jiang X, Rodriguez L, Shen YL, et al. FDA approval summary: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab for the treatment of patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:1836–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1989;8:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donne R, Lujambio A. The liver cancer immune microenvironment: therapeutic implications for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77:1773–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited—the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akhtar M, Haider A, Rashid S, Al-Nabet ADMH. Paget’s “seed and soil” theory of cancer metastasis: An idea whose time has come. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ricard-Blum S. The collagen family. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hulmes DJS. Building Collagen Molecules, Fibrils, and Suprafibrillar Structures. J Struct Biol. 2002;137:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shi R, Zhang Z, Zhu A, Xiong X, Zhang J, Xu J, et al. Targeting type I collagen for cancer treatment. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:665–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen Y, Kim J, Yang S, Wang H, Wu CJ, Sugimoto H, et al. Type I collagen deletion in αSMA+ myofibroblasts augments immune suppression and accelerates progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:548–65.e546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vuorio E, de Crombrugghe B. The family of collagen genes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:837–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shoulders MD, Raines RT. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:929–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gelse K, Pöschl E, Aigner T. Collagens—structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1531–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naomi R, Ridzuan PM, Bahari H. Current insights into collagen type I. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13:2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buechler MB, Fu W, Turley SJ. Fibroblast-macrophage reciprocal interactions in health, fibrosis, and cancer. Immunity. 2021;54:903–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Su H, Karin M. Collagen architecture and signaling orchestrate cancer development. Trends Cancer. 2023;9:764–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sprangers S, Everts V. Molecular pathways of cell-mediated degradation of fibrillar collagen. Matrix Biol. 2019;75-76:190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fields GB. Interstitial collagen catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8785–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arora PD, Manolson MF, Downey GP, Sodek J, McCulloch CAG. A novel model system for characterization of phagosomal maturation, acidification, and intracellular collagen degradation in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35432–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosenblum G, Van den Steen PE, Cohen SR, Bitler A, Brand DD, Opdenakker G, et al. Direct visualization of protease action on collagen triple helical structure. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Madsen DH, Ingvarsen S, Jürgensen HJ, Melander MC, Kjøller L, Moyer A, et al. The non-phagocytic route of collagen uptake: A distinct degradation pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26996–7010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bi Y, Mukhopadhyay D, Drinane M, Ji B, Li X, Cao S, et al. Endocytosis of collagen by hepatic stellate cells regulates extracellular matrix dynamics. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C622–C633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim SI, Na HJ, Ding Y, Wang Z, Lee SJ, Choi ME. Autophagy promotes intracellular degradation of type I collagen induced by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11677–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Najafi M, Farhood B, Mortezaee K. Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and degradation as cancer drivers. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:2782–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uchugonova A, Zhao M, Weinigel M, Zhang Y, Bouvet M, Hoffman RM, et al. Multiphoton tomography visualizes collagen fibers in the tumor microenvironment that maintain cancer-cell anchorage and shape. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makareeva E, Han S, Vera JC, Sackett DL, Holmbeck K, Phillips CL, et al. Carcinomas contain a matrix metalloproteinase-resistant isoform of type I collagen exerting selective support to invasion. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jabłońska-Trypuć A, Matejczyk M, Rosochacki S. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the main extracellular matrix (ECM) enzymes in collagen degradation, as a target for anticancer drugs. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2016;31:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barbazan J, Pérez-González C, Gómez-González M, Dedenon M, Richon S, Latorre E, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts actively compress cancer cells and modulate mechanotransduction. Nat Commun. 2023;14:6966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Su H, Yang F, Fu R, Trinh B, Sun N, Liu J, et al. Collagenolysis-dependent DDR1 signalling dictates pancreatic cancer outcome. Nature. 2022;610:366–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, Du WX, Li RG, Yang J, et al. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: Biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roy AM, Iyer R, Chakraborty S. The extracellular matrix in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms and therapeutic vulnerability. Cell Rep Med. 2023;4:101170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cox TR. The matrix in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:217–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Di Martino JS, Nobre AR, Mondal C, Taha I, Farias EF, Fertig EJ, et al. A tumor-derived type III collagen-rich ECM niche regulates tumor cell dormancy. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:90–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nicolas-Boluda A, Vaquero J, Vimeux L, Guilbert T, Barrin S, Kantari-Mimoun C, et al. Tumor stiffening reversion through collagen crosslinking inhibition improves T cell migration and anti-PD-1 treatment. Elife. 2021;10:e58688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma L, Heinrich S, Wang L, Keggenhoff FL, Khatib S, Forgues M, et al. Multiregional single-cell dissection of tumor and immune cells reveals stable lock-and-key features in liver cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lebbink RJ, de Ruiter T, Adelmeijer J, Brenkman AB, van Helvoort JM, Koch M, et al. Collagens are functional, high affinity ligands for the inhibitory immune receptor LAIR-1. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1419–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xiong Y, Zhang X, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Pan Y, Wu Y, et al. Collagen I-DDR1 signaling promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell stemness via Hippo signaling repression. Cell Death Differ. 2023;30:1648–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yao T, Hu W, Chen J, Shen L, Yu Y, Tang Z, et al. Collagen XV mediated the epithelial-mesenchymal transition to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;13:2472–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Larsen AMH, Kuczek DE, Kalvisa A, Siersbæk MS, Thorseth ML, Johansen AZ, et al. Collagen density modulates the immunosuppressive functions of macrophages. J Immunol. 2020;205:1461–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Salmon H, Franciszkiewicz K, Damotte D, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Validire P, Trautmann A, et al. Matrix architecture defines the preferential localization and migration of T cells into the stroma of human lung tumors. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:899–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wells RG. The role of matrix stiffness in regulating cell behavior. Hepatology. 2008;47:1394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Akima T, Tamano M, Hiraishi H. Liver stiffness measured by transient elastography is a predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma development in viral hepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:965–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Olsen AL, Bloomer SA, Chan EP, Gaça MDA, Georges PC, Sackey B, et al. Hepatic stellate cells require a stiff environment for myofibroblastic differentiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G110–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lachowski D, Cortes E, Robinson B, Rice A, Rombouts K, Del Río Hernández AE. FAK controls the mechanical activation of YAP, a transcriptional regulator required for durotaxis. Faseb j. 2018;32:1099–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ma HP, Chang HL, Bamodu OA, Yadav VK, Huang TY, Wu ATH, et al. Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1) is a reliable biomarker and putative therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinogenesis and metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang T, Jin H, Hu J, Li X, Ruan H, Xu H, et al. COL4A1 promotes the growth and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating FAK-Src signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang S, Zhou M, Xia Y. COL15A1 interacts with P4HB to regulate the growth and malignancy of HepG2.2.15 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;681:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu Y, Zhang X, Yang B, Zhuang H, Guo H, Wei W, et al. Demethylation-induced overexpression of Shc3 drives c-Raf-independent activation of MEK/ERK in HCC. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fischer RS, Sun X, Baird MA, Hourwitz MJ, Seo BR, Pasapera AM, et al. Contractility, focal adhesion orientation, and stress fiber orientation drive cancer cell polarity and migration along wavy ECM substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2021135118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sun X, Wu B, Chiang HC, Deng H, Zhang X, Xiong W, et al. Tumour DDR1 promotes collagen fibre alignment to instigate immune exclusion. Nature. 2021;599:673–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Atallah AM, Albannan MS, EL-Deen MS, Farid K, Khedr FM, Attallah KA, et al. Diagnostic role of collagen-III and matrix metalloproteinase-1 for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Biomed Sci. 2020;77:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stylianou A, Voutouri C, Mpekris F, Stylianopoulos T. Pancreatic cancer presents distinct nanomechanical properties during progression. Ann Biomed Eng. 2023;51:1602–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wahyudi H, Reynolds AA, Li Y, Owen SC, Yu SM. Targeting collagen for diagnostic imaging and therapeutic delivery. J Control Release. 2016;240:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wight TN, Potter-Perigo S. The extracellular matrix: An active or passive player in fibrosis? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G950–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhao W, Lv M, Yang X, Zhou J, Xing B, Zhang Z. Liver tumor-initiating cells initiate the formation of a stiff cancer stem cell microenvironment niche by secreting LOX. Carcinogenesis. 2022;43:766–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Desert R, Chen W, Ge X, Viel R, Han H, Athavale D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinomas, exhibiting intratumor fibrosis, express cancer-specific extracellular matrix remodeling and WNT/TGFB signatures, associated with poor outcome. Hepatology. 2023;78:741–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tvaroška I. Glycosylation modulates the structure and functions of collagen: A review. Molecules. 2024;29:1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dawood RM, El-Meguid MA, Salum GM, El Awady MK. Key players of hepatic fibrosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2020;40:472–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tanaka Y, Tateishi R, Koike K. Proteoglycans are attractive biomarkers and therapeutic targets in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tse APW, Sze KMF, Shea QTK, Chiu EYT, Tsang FHC, Chiu DKC, et al. Hepatitis transactivator protein X promotes extracellular matrix modification through HIF/LOX pathway in liver cancer. Oncogenesis. 2018;7:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wang T, Fu X, Jin T, Zhang L, Liu B, Wu Y, et al. Aspirin targets P4HA2 through inhibiting NF-κB and LMCD1-AS1/let-7g to inhibit tumour growth and collagen deposition in hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:168–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Fan W, Adebowale K, Váncza L, Li Y, Rabbi MF, Kunimoto K, et al. Matrix viscoelasticity promotes liver cancer progression in the pre-cirrhotic liver. Nature. 2024;626:635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sigrist RMS, Liau J, Kaffas AE, Chammas MC, Willmann JK. Ultrasound elastography: Review of techniques and clinical applications. Theranostics. 2017;7:1303–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lin L, Chen G, Chen Z, Lu J, Zhu W, Zhong J, et al. Prognostic value of tumor stromal collagen features in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by second-harmonic generation microscopy. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;116:104513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Huang Y, de Boer WB, Adams LA, MacQuillan G, Bulsara MK, Jeffrey GP. Image analysis of liver biopsy samples measures fibrosis and predicts clinical outcome. J Hepatol. 2014;61:22–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ueda J, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Yoshioka M, Hirakata A, et al. Evaluation of the impact of preoperative values of hyaluronic acid and type IV collagen on the outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu Y, Zhang J, Chen Y, Sohel H, Ke X, Chen J, et al. The correlation and role analysis of COL4A1 and COL4A2 in hepatocarcinogenesis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:204–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhou H, Su L, Liu C, Li B, Li H, Xie Y, et al. CTHRC1 may serve as a prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7823–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Chen YL, Wang TH, Hsu HC, Yuan RH, Jeng YM. Overexpression of CTHRC1 in hepatocellular carcinoma promotes tumor invasion and predicts poor prognosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yan L, Xu F, Dai C. Overexpression of COL24A1 in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts poor prognosis: A study based on multiple databases, clinical samples and cell lines. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:2819–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhang X, Zhang H, Liao Z, Zhang J, Liang H, Wang W, et al. SHC4 promotes tumor proliferation and metastasis by activating STAT3 signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervás-Stubbs S, Melero I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:525–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Peng DH, Rodriguez BL, Diao L, Chen L, Wang J, Byers LA, et al. Collagen promotes anti-PD-1/PD-L1 resistance in cancer through LAIR1-dependent CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Liang H, Li X, Wang B, Chen B, Zhao Y, Sun J, et al. A collagen-binding EGFR antibody fragment targeting tumors with a collagen-rich extracellular matrix. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Katsumata K, Ishihara J, Mansurov A, Ishihara A, Raczy MM, Yuba E, et al. Targeting inflammatory sites through collagen affinity enhances the therapeutic efficacy of anti-inflammatory antibodies. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaay1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ren T, Jia H, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Ma Q, Yao D, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling: Synergistic effect of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and bevacizumab. Front Oncol. 2022;12:829059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dong G, Ma M, Lin X, Liu H, Gao D, Cui J, et al. Treatment-damaged hepatocellular carcinoma promotes activities of hepatic stellate cells and fibrosis through GDF15. Exp Cell Res. 2018;370:468–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Xia SW, Wang ZM, Sun SM, Su Y, Li ZH, Shao JJ, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and protein degradation in chronic liver disease. Pharmacol Res. 2020;161:105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Song Y, Kim JS, Choi EK, Kim J, Kim KM, Seo HR. TGF-β-independent CTGF induction regulates cell adhesion mediated drug resistance by increasing collagen I in HCC. Oncotarget. 2017;8:21650–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Qu C, He L, Yao N, Li J, Jiang Y, Li B, et al. Myofibroblast-specific Msi2 knockout inhibits HCC progression in a mouse model. Hepatology. 2021;74:458–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Thomas D, Rathinavel AK, Radhakrishnan P. Altered glycosylation in cancer: A promising target for biomarkers and therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1875:188464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhang X, Hu Y, Pan Y, Xiong Y, Zhang Y, Han M, et al. DDR1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through recruiting PSD4 to ARF6. Oncogene. 2022;41:1821–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]