Abstract

Introduction

Persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) is the causal agent of several cancers including cervical, anal and oropharyngeal cancer. Transgender men and transmasculine non-binary (TMNB) people with a cervix are much less likely to undergo cervical cancer screening than cisgender women. Transgender women and transfeminine non-binary (TWNB) people assigned male at birth may be at increased risk of HPV. Both TMNB and TWNB people face many barriers to HPV testing including medical mistrust due to stigma and discrimination.

Methods and analysis

The Self-TI Study (Self-TI) is a pilot study designed to measure acceptability and feasibility of HPV self-testing among transgender and non-binary people in England. TMNB people aged 25–65 years, with at least 1 year of testosterone, and TWNB people, aged 18 years and over, are eligible to participate. Participants self-collect up to four samples: an oral rinse, a first void urine sample, a vaginal swab (if applicable) and an anal swab. TMNB participants are asked to have an additional clinician-collected cervical swab taken following their routine Cervical Screening Programme sample. TWNB people are asked to take a self-collection kit to perform additional self-collection at home and mail the samples back to the clinic. Acceptability is assessed by a self-administered online survey and feasibility is measured as the proportion of samples returned in the clinic and from home.

Ethics and dissemination

Self-TI received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Wales 4 and ethical review panel within the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the US National Cancer Institute. Self-TI was coproduced by members of the transgender and non-binary community, who served as authors, collaborators and members of the patient and public involvement (PPI) group. Results of this study will be shared with the community prior to being published in peer-reviewed journals and the PPI group will help to design the results dissemination strategy. The evidence generated from this pilot study could be used to inform a larger, international study of HPV self-testing in the transgender and non-binary community.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Human Papillomavirus Viruses, Transgender Persons, Uterine Cervical Neoplasms, Health Equity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The pilot study addresses the lack of evidence around acceptability of human papillomavirus (HPV) self-sampling in transgender and non-binary people and was codesigned with community members.

This pilot study collects samples from four body sites including an oral rinse, a urine sample, a vaginal swab and an anal swab to assess correlation between samples.

This pilot study examines the concordance between self-collected and clinician-collected samples.

This pilot study offers participants an at-home collection kit to assess the feasibility of HPV testing at home.

The generalisability of study findings is limited due to the convenience sampling of participants.

Introduction

Persistent infection with 1 of the 12 high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes is the causative agent of several cancers including cervical, anogenital and oropharyngeal.1 The widespread implementation of cervical cancer screening with Pap cytology or HPV testing, combined with HPV vaccination, has greatly reduced cervical cancer incidence and mortality.2 Consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening now include transgender women.3 4

Transgender men and transmasculine non-binary (TMNB) adults (those who were registered female at birth and have a masculine or non-binary gender identity) are less likely to have ever undergone cervical cancer screening than cisgender women.5 6 As many as one-third of TMNB adults are not up to date with recommended screening guidelines.7 8 Among those screened, TMNB patients are eight times more likely than cisgender women to have an inadequate Pap where the test cannot be evaluated for a variety of reasons such as lack of sufficient cellularity or bleeding resulting from testosterone induced cervical and vaginal atrophy.9 TMNB adults face many additional barriers to cervical cancer screening than cisgender people, including an increased likelihood of discrimination in medical settings.10–12 During gynaecologic examinations, TMNB patients may experience gender dysphoria (distress associated with the incongruence between gender identity and sex registered at birth) due to the focus on genitalia and the gendered nature of cervical cancer screening, such as feminine waiting rooms and expectations of gender conformity.13–15 Clinicians may also erroneously believe that TMNB people are not a risk for HPV due to incorrect assumptions about TMNB anatomy and sexual practices and are less likely to recommend screening.14 Further, TMNB patients may be less likely to be vaccinated against HPV than cisgender women.16

Transgender women and transfeminine non-binary (TWNB) adults (those who were registered male at birth and have a female or non-binary gender identity) may be at increased risk of HPV infection compared with cisgender individuals. England began a national HPV immunisation programme for adolescent girls with the bivalent HPV vaccine in 2008, switching to the quadrivalent in 2012 and the nonavalent in 2021.17 18 The UK implemented a gender-neutral vaccination programme in 2019 with a catch-up programme for people up to the age of 45 years who are considered at high risk for HPV (eg, men who have sex with men).19 Though transgender and non-binary people may be eligible for vaccination through the catch-up programme, barriers to healthcare and lack of perceived risk means that many TWNB adults may still be unvaccinated.20 Additionally, coinfection with HIV, which may be elevated among TWNB adults compared with the general population,21 increases the risk of persistent HPV infection22–24 and HPV-associated cancers.25 26 One small US study reported HPV prevalence of 89% in anal and 9% in oral specimens from TWNB adults.27 A Brazilian study of 268 transgender women reported a study prevalence to be 77% in anal, 34% in genital and 11% oral specimens.28 Studies from both The Netherlands and Thailand estimate a 20% prevalence of neovaginal high-risk HPV, though these two studies had a high proportion of invalid HPV results, suggesting the true prevalence may be higher.29 30 The oncogenic potential of persistent high-risk HPV infection in the vagina of TWNB is poorly understood and current guidelines do not recommend screening for this population.31 Both low-grade and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions have been reported in the vagina of TWNB adults but incidence data is lacking.32 33

Prior research conducted in cisgender women (largely from high-income countries) has shown that self-sampling for HPV with PCR-based assays has comparable performance to clinician-collected samples for the detection of cervical HPV.34 35 Limited research suggests that most TMNB patients may prefer HPV testing by self-collection,36 37 though patients have expressed concern about the lack of evidence-based guidelines specific to TMNB to inform their preference.36 38 Indeed, only one small study39 has compared the performance of clinician-collected and self-collected samples in TMNB, showing good concordance; however, more research is needed to assess whether this is an acceptable approach for cervical screening in TMNB. Reisner et al 40 found a study HPV prevalence of 16% among 130 TM participants and that HPV testing by self-sample showed good concordance with clinician-collected samples. Similarly, one US study that included TWNB adults found that people were more likely to engage in anal cancer screening with an at-home self-collection kit than attend a clinician-collected screening appointment.41

In this study, we present the protocol for the Self-TI Study (Self-TI), a pilot study whose objective is to assess the feasibility and acceptability of HPV self-testing at four body sites among TMNB and TWNB adults.

Methods and analysis

Study design and setting

Self-TI is a pilot study examining the acceptability and feasibility of HPV self-testing among transgender and non-binary people conducted in England (IRAS# 319 364 and clincialtrials.gov NCT05883111).

Study setting and participant recruitment

Enrolment began in February 2024 and will continue for 1 year. Self-TI seeks to enrol 50 participants who identify as TMNB with a cervix and 50 participants who identify as TWNB assigned male at birth. Participants are recruited at one of the three clinical sites in England: CliniQ or Ambrose King sexual health clinics in London or Clinic-T in Brighton. These sites were chosen as they are in areas with large transgender and non-binary populations, their providers are specialists in transgender and non-binary sexual health and the clinic staff have experience conducting research studies. Participants can be recruited and prescreened for study eligibility when they book an appointment for a cervical cancer screening (TMNB study group only) or a sexual health screening (TWNB study group only). Recruitment occurs through advertisement posters and banners placed in the clinics and flyers placed in gender identity clinics and general practitioners’ offices known to have transgender and non-binary patients. Self-TI has created a website (https://www.self-ti.com/)that contains information on the study, HPV and cancer education and links to contact the study sites to enrol. Self-TI also commissioned a well-known trans activist and artist in England, to record a 45 s advertisement video. This video is posted on the activist’s social media sites (Twitter, Instagram and TikTok), other LGBTQ+ cancer charities in England and the Self-TI’s website and social media sites. The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials checklist is available as an online supplemental file.42

bmjopen-2024-086099supp001.pdf (819.7KB, pdf)

Participants

Individuals who identify as TMNB with a cervix, aged 25–65 years and with at least 1 year of self-reported testosterone therapy, are eligible to participate in the TMNB study group. Testosterone exposure is a requirement of study participation as it is associated with vaginal atrophy such that speculum and swab insertion to the recommended depth could be painful, unpleasant or necessitate additional lubricant affecting the accuracy and acceptability of clinician-collected and self-collected HPV testing.9 40 Individuals who identify as TWNB, aged 18 years and over, are eligible to participate in the TWNB study group. TWNB participants with a vagina are preferentially selected into the study, with the first 3 months of enrolment restricted to individuals who had undergone vaginoplasty. After 3 months, the study team will evaluate whether it is feasible to reach the targeted sample size with this restriction and if not, the eligibility criterion will be removed. Individuals with a vagina must have undergone vaginoplasty more than 1 year prior to entering the study due to safety concerns over self-sampling on recently healed epithelium. All participants are given a participant information sheet, which is discussed with study staff as part of informed consent procedures.

Data collection

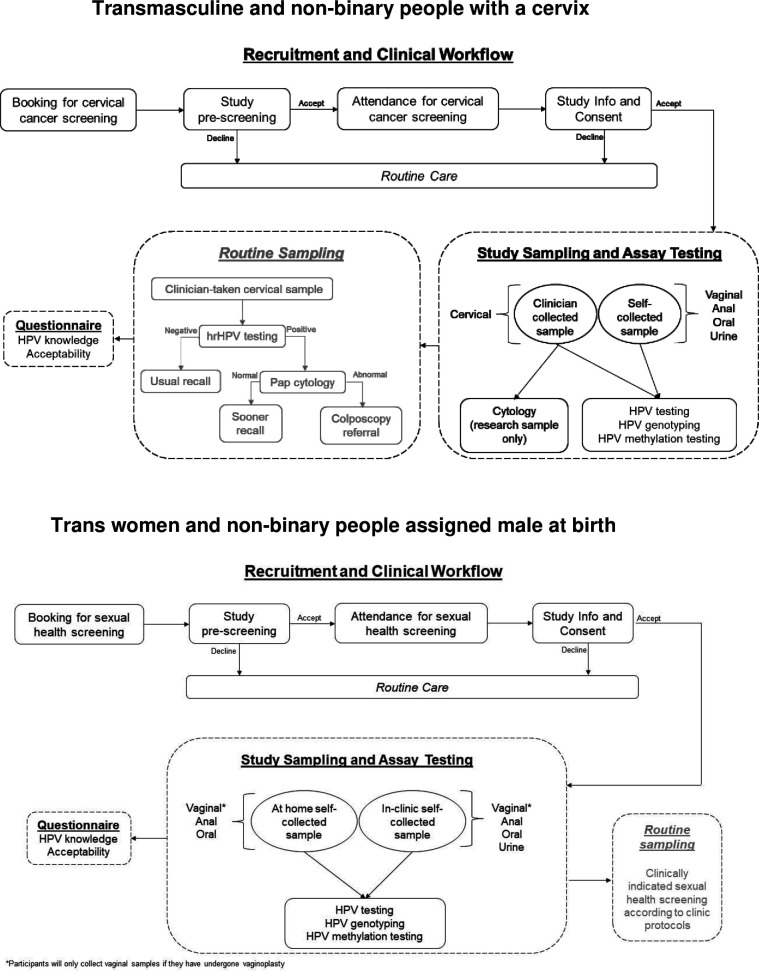

Study activities and timeline are presented in table 1 and figure 1. After giving consent, participants fill out demographics and medical history questionnaires. The demographics form asks for sexual orientation, race and ethnicity, height and weight. The medical history form asks about previous cancer screening, previous cancer diagnoses, HPV vaccination, hormone therapy and HIV status. Study staff review these questionnaires with the participants to make sure they are complete and to answer any questions the participants have.

Table 1.

Study activities and timeline

| Study procedure | Prior to day 1 | In clinic Day 1 |

At home≤4 weeks (TWNB only) | |

| Screening | Clinician | Self-sampling | Self-sampling | |

| Eligibility assessment | X | |||

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Demographics | X | |||

| Medical history | X | |||

| Vaginal swab | X* | X* | ||

| Anal swab | X | X | ||

| Oral rinse | X | X | ||

| Urine | X | |||

| Cervical swab | X (TMNB only) | |||

| Survey | X (TMNB only) | X | ||

| Adverse event assessment | X | X | X | |

*All TMNB and only TWNB who have undergone vaginoplasty.

TMNB, transmasculine and non-binary people with a cervix; TWNB, transfeminine and non-binary people assigned male at birth.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. HPV, human papillomavirus.

Sampling

All participants are asked to self-collect samples in the clinic in the following order: oral rinse, urine, vagina and anus (collection materials are provided in table 2). Each participant will receive a self-sampling kit with written instructions for self-collection that include a QR code linked to an instructional video. Study staff will also explain the self-collection procedures to the participants.

Table 2.

Collection materials of study specimens

| Specimen type | Collection method |

| Vaginal/neovaginal | Evalyn Brush (Rovers Medical, Belgium) or Dacron swab (DuPont, USA) |

| Anal | FLOQSwab (COPAN Diagnostics, USA) |

| Oral rinse | Scope (Proctor and Gamble, USA) |

| Urine | Colli-Pee (Novosanis, Belgium) |

| Cervical | Endocervical broom (Hologic, USA) |

The participants use Scope mouthwash (Proctor and Gamble, USA) to collect buccal cells and a Colli-pee collection device (Novosanis, Belgium) to collect first void urine (table 2). The Colli-pee device was selected as it has been used successfully by sexual and gender minority participants in other studies and can accommodate a variety of genital anatomies.

For the vaginal sample, participants have a choice to use either an Evalyn Brush (Rovers Medical, Belgium) or a Dacron swab (DuPont, USA) (table 2), if applicable. The Evalyn Brush was chosen for several features which make it easier to use for populations unfamiliar with self-sampling. It has wings to guide the participant as to how far they should insert the device, a plunger which releases the bristle brush to the cervix and clicks to aid in the counting of the rotations. Participants who prefer a slimmer vaginal swab are provided with a Dacron swab on request (table 2). Participants use a FLOQSwab (COPAN Diagnostics, USA) to collect the anal sample (table 2). The choice of sampling methods was based on a review of previous studies that examined the same body sites and concordance between in-clinic and at-home sampling methods,43 44 though the mailing of dry swabs without transport media may affect anal specimen adequacy, especially if faecal matter is present.45

After the self-administered samples are collected, TMNB participants have a pelvic examination as part of the standard cervical cancer screening. In England, individuals with a cervix are invited to participate in the National Cervical Screening Programme (CSP) every 3 years for those between the age of 25 and 49 years and every 5 years for those between the age of 50 and 65 years. Screening is conducted with a primary HPV test and if positive, a reflex cervical sample is sent for cytology. Self-TI is paired with the CSP so that TMNB individuals do not need to undergo pelvic examinations more than once. The clinician will take two cervical swabs; the first for the CSP sent to the National Health Service (NHS) laboratories, and the second for the clinician-collected sample for Self-TI using an endocervical broom (Hologic, USA). The CSP sample is collected first so that if the participant declines further samples, the standard of care is met.

After TWNB participants collect their self-administered samples, they will be given a kit to complete a second vaginal (if applicable), anal and oral rinse sampling at home. Once collected, the participant places the dry brushes and samples in the pre-addressed, postage paid mailer provided before dropping it in the post within 1 month of their first study visit. The kit includes written instructions with a QR code linked to an instructional video. Study staff follow-up with TWNB study participants on a weekly basis for up to 4 weeks to ensure the return of their study samples.

Self-administered online survey

After self-collection, participants take a self-administered online survey, which takes approximately 20–25 min to complete. The survey includes questions based on previously validated surveys that capture sensitive demographic characteristics, acceptability of self-sampling (eg, physical and emotional comfort, confidence in collection), comparing self-collected to clinician-collected sampling (TMNB study group only),39 comparing self-collected sampling in the clinic to at-home collection (TWNB study group only), a history of HPV vaccination, knowledge of HPV,39 comparing self-collected to clinician-collected sampling (TMNB study group only), medical mistrust46 and a sexual history.39 47 Participants receive a £20 gift card to a large online retailer, as remuneration for their participation in Self-TI.

Outcomes

The primary study outcomes are the acceptability and feasibility of self-sampling among participants that will inform a larger study. Acceptability is measured by the physical and emotional responses to self-sampling for each collection method using a 7-point Likert scale. Feasibility is measured by the proportion of specimens returned from self-collection in the clinic and those mailed from home.

This pilot study will also estimate the study prevalence of HPV (positivity and genotype) and the correlation of HPV detection between the four self-collected samples. The concordance between the vaginal self-collected sample and clinician-collected cervical sample will be estimated among TMNB. Among TWNB, we will estimate the correlation between the samples collected by participants in the clinic with the samples collected at home. Finally, Self-TI will collect exploratory data on risk factors associated with HPV prevalence, which can be fully assessed in a larger trial.

HPV testing

The cervical, vaginal and anal swabs are reconstituted in a plastic vial with PreservCyt transport medium (ThinPrep PreservCyt Solution, Hologic, USA) before freezing at −80°C. Oral and urine samples are placed directly into −80°C. Samples are shipped in batches to the Center for Genomic Research (CGR) at National Cancer Institute (NCI). All samples will be tested using a next-generation sequencing based-assay (TypeSeq) developed by CGR, which generates a positive/negative result for 51 HPV genotypes.48

Data management

Data management and project co-ordination is done at the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at NCI. Study oversight and data management are led by the study chief investigator (AMB) and the statistician (SSJ). Research staff enter deidentified participant data into an electronic data capture system. All participant information (including laboratory data) is confidential and stored in a secure location. Only the personnel listed on the delegation log will have access to participant data; the statistician and laboratory personnel have access to deidentified data only. Participant data are checked at regular intervals for quality assurance. The number of adverse events (AEs) is expected to be very small and thus an independent data monitoring committee was not appointed. However, all AEs will be collected, and severe AEs deemed by the chief investigator to be related to study procedures and unexpected will be reported to the sponsor within 24 hours and to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) within 15 days of learning of the event.

Statistical analysis

Acceptability of self-sampling procedures will be measured by a self-administered online survey, which uses a 7-point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 7 indicating strong agreement. Summary measures of these questions will be reported (average score for each question) separately for each group. For all participants, feasibility will be measured by the proportion of participants who are able to complete the self-collection procedures in the clinic. For TWNB participants, at-home feasibility will be measured by the proportion of TWNB participants who are able to complete and return all self-collection procedures at home.

For our secondary objectives, we will estimate the prevalence of HPV, overall, and by genotype in each of the self-collected samples from the two groups, separately. The phi-coefficient and associated p values will be estimated to assess HPV positivity correlation between the four anatomic sites. Further, we will calculate the Cohen’s kappa statistic as a measure of percent positive agreement of HPV positivity in self-collected vaginal samples versus the clinician-collected cervical samples among TMNB and in self-collected in clinic samples versus self-collected at home samples among TWNB, respectively.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

A PPI group was formed prior to the submission of the Self-TI protocol to regulatory bodies. PPI played an important role in the design and conduct of the study and participant recruitment. Six group meetings were held between May 2022 and August 2023 with six members. PPI members represented the target population of Self-TI, including transfeminine, transmasculine and non-binary individuals. SSJ, SOC and EW attended all meetings, which were led either by SOC or EW who are members of the transgender and non-binary community, and SOC is the founder of a cancer charity for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer individuals. PPI members reviewed the study protocol, data collection forms, online self-administered survey, advertisement and recruitment plan, instructional video and results dissemination plan. Meetings were conducted over Zoom in the evenings to accommodate members’ schedules and followed up via email to provide additional opportunities for written feedback on materials. Online meetings included short presentations on HPV-related cancer topics given by experts in the field to provide information exchange. PPI members were compensated for their time with multiretailer gift cards to an amount in line with National Institute for Health Research guidelines.

Several important suggestions were made by the PPI group and adopted into the study protocol. The standard Evalyn brush is manufactured in a dark pink colour, which was suggested could be off putting to our participants, so we worked with the manufacturers to provide Self-TI with devices in a more neutral blue colour. Though the Evalyn brush has several features that make it ideal for individuals who are not familiar with self-sampling, one drawback is that it is slightly thicker than other swabs used for vaginal sampling. Therefore, it was suggested by the PPI group that participants be provided with a slimmer swab on request. Additionally, though it is preferred that TMNB participants complete the survey in the clinic after their examination, the PPI group felt that participants should be given the option to complete the survey at home. This change was implemented and TMNB participants can scan or be emailed a QR code to the survey link after leaving the clinic if desired. The group felt that some participants would want to leave the clinic immediately after their speculum examination as it may result in increased feelings of dysphoria and can be uncomfortable or painful for some participants.

Ethics and dissemination

The study received ethical approval from the REC of Wales 4 (#23/WA/0266) and the ethical review panel within the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the US NCI (#3G009-05). Amendments to the protocol and study materials are approved by the REC and the protocol was last revised on 23 January 2024 (4th revision). Before taking part in this pilot study, all participants provide informed written consent to participate to the study staff. Participants are asked if they consent to future use of their research specimens; otherwise specimens will be destroyed after the aims of the study protocol are met. People with a male gender marker in their medical record are not invited to participate in the CSP and the laboratory may reject cervical samples from male patients. The chief investigator worked with the laboratories processing CSP samples for Self-TI participants to ensure samples would not be discarded prior to testing. Senior staff (AMB and SSJ) also consulted the US National Institutes of Health Bioethics group about returning study results to the participants. Because the assay under study in Self-TI is a research test and not approved for clinical use in the UK, participants will not have their study results returned to them. Instead, TMNB participants should defer to the HPV result provided by the CSP, as applicable. Further, in cases where the HPV result from Self-TI conflicts with the CSP result or in the absence of a CSP result (as in the case of TWNB samples), senior study staff felt that providing participants with a result that could not be followed up with clinically could cause distress and would be unethical. Only HPV positive results taken from samples as part of the CSP will warrant follow-up under the NHS.

Information gained from this study will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international conferences. Prior to scientific dissemination, we will engage with the PPI group in writing the lay results, results dissemination strategy and final publication. The lay summary of the results will be posted to the Self-TI website, participating clinic websites and the websites of charities and organisations supporting trans and non-binary people so that study participants and community members may be notified of the results first at the PPI group’s request. Several online webinars are planned to disseminate the results and allow community members to engage in a discussion with the researchers. These webinars will be recorded and posted on the Self-TI website. Finally, data from this pilot study will inform a larger, multicentre, international study.

Discussion

The overarching goal of this pilot study is to provide important insight into the acceptability and feasibility of HPV self-sampling among transgender and gender diverse individuals for a larger study. The pilot study will provide essential data that will inform recruitment, study procedures and sample size calculations for this larger study.

A major strength of our study is community involvement from conception to implementation. We included community voices at every stage of protocol development and have had a dedicated PPI group in addition to transgender and non-binary senior study staff advising our study throughout. This strategy has led to improved advertisements, study materials and outreach efforts. Continued work with community members will help us disseminate study results to a wider audience.

Potential study limitations include the inability to generalise our results to the wider transgender population in England as we used sexual health clinics in two major cities to recruit our participants. Compared with the general population of transgender individuals, our study participants may be more engaged in care, have greater access to care and have higher health seeking behaviours. This recruitment strategy was chosen to maximise the proportion of positive HPV tests, to enable recruitment of a reasonable sample size in a short amount of time. Our decision to use dry swabs for anal sampling may affect acceptability as dry swabs were reported to cause pain in 19% of users49 as well as adequacy as the presence of faeces was shown to inhibit HPV assays.45 Finally, the implementation of HPV self-sampling methods and strategies may reduce barriers for transgender and non-binary people in high-resourced areas, but barriers will remain for individuals who live in areas where there is widespread discrimination resulting in a lack of access to culturally appropriate screening.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Self-TI participants and Fox Fisher for voiceover of the instructions in video and study promotion. The authors would like to specially thank the members of the PPI group and Emrah Onal.

Footnotes

@Ejoeyward

Collaborators: Self-TI Study group: Affiliated with the Caldecot Centre and CliniQ at King’s College Hospital NHS Trust: Ellen Adams, Kate Flanagan, Lucy Campbell and Birgit Barbini; Brighton and Howe Sexual Health Clinic: Sophie Ross and Lisa Barbour; Ambrose King Centre: Kyle Ring and James Hand; and Center for Genomic Research at the National Cancer Institute: Amy Hutchinson and Casey Dagnell.

Contributors: AMB and SSJ conceived, designed and supervised the study and are responsible for data management. SSJ, CO, and AMB were responsible for costings, ethics approval, and study set-up. SSJ drafted the manuscript. MAC supervised the HPV methylation assay and provided several methodological contributions. SOC maintains the study website. SSJ, SOC and EW oversaw the co-ordination of the PPI group. AMB, SSJ, SOC and EW were responsible for creating the study survey. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final draft. SSJ is the guarantor.

Funding: Self-TI was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland, USA (Grant no.: NA). The PPI group was funded by the Centre for Public Engagement, Queen Mary University of London (Grant no.: NA). Sponsorship information: Queen Mary University of London, Dr Mays Jawad, Research Governance Operations Manager, Joint Research Management Office, research.governance@qmul.ac.uk. Sponsors references: IRAS Number: 319364; Edge Number: 155220.

Competing interests: AMB is a trustee of OUTpatients, of which SOC is the CEO. None of the other authors have any conflicts to declare.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods and analysis section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e180–90. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sasieni P, Castanon A, Cuzick J. Effectiveness of Cervical screening with age: population based case-control study of prospectively recorded data. BMJ 2009;339:b2968. 10.1136/bmj.b2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stier EA, Clarke MA, Deshmukh AA, et al. International Anal Neoplasia society’s consensus guidelines for anal cancer screening. Intl Journal of Cancer 2024;154:1694–702. 10.1002/ijc.34850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palefsky JM, Lee JY, Jay N, et al. Treatment of Anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions to prevent Anal cancer. N Engl J Med 2022;386:2273–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa2201048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart T, Lee YA, Damiano EA. Do Transgender and gender diverse individuals receive adequate gynecologic care? an analysis of a rural academic center. Transgend Health 2020;5:50–8. 10.1089/trgh.2019.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark MA, Boehmer U, Rosenthal S. Cancer screening in Lesbian and Bisexual women and Transmen. In: Boehmer U, Elk R, eds. Cancer and the LGBT Community. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2015: 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peitzmeier SM, Khullar K, Reisner SL, et al. Pap test use is lower among female-to-male patients than non-transgender women. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:808–12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tabaac AR, Sutter ME, Wall CSJ, et al. Gender identity disparities in cancer screening behaviors. Am J Prev Med 2018;54:385–93. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peitzmeier SM, Reisner SL, Harigopal P, et al. Female-to-male patients have high prevalence of unsatisfactory paps compared to non-Transgender females: implications for Cervical cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:778–84. 10.1007/s11606-013-2753-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. James SE, Herman JL, Keisling M, et al. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, D.C: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seay J, Ranck A, Weiss R, et al. Understanding transgender men’s experiences with and preferences for cervical cancer screening: a rapid assessment survey. LGBT Health 2017;4:304–9. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agénor M, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein IM, et al. Perceptions of cervical cancer risk and screening among transmasculine individuals: patient and provider perspectives. Cult Health Sex 2016;18:1192–206. 10.1080/13691058.2016.1177203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Potter J, Peitzmeier SM, Bernstein I, et al. Cervical cancer screening for patients on the female-to-male spectrum: a narrative review and guide for Clinicians. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1857–64. 10.1007/s11606-015-3462-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berner AM, Connolly DJ, Pinnell I, et al. Attitudes of Transgender men and non-binary people to cervical screening: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study in the UK. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71:e614–25. 10.3399/BJGP.2020.0905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown B, Poteat T, Marg L, et al. Human Papillomavirus-related cancer surveillance, prevention, and screening among Transgender men and women: neglected populations at high risk. LGBT Health 2017;4:315–9. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Public Health England . Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Coverage in England, 2008/09 to 2013/14: A review of the full six years of the three-dose schedule 2015, Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c4f232ced915d7d3953d207/HPV_Vaccine_Coverage_in_England_200809_to_201314.pdf [Accessed 16 Jan 2024].

- 18. Public Health England . Changes to the vaccine of the HPV immunisation programme, 2021. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60feecf38fa8f5043b11e46a/HPV_letter_changes_to_the_vaccine_of_the_HPV_immunisation_programme__July_2021.pdf

- 19. National Health Service . HPV vaccine. 2023. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/hpv-human-papillomavirus-vaccine/ [Accessed 13 Feb 2024].

- 20. Information on HPV vaccination . Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hpv-vaccine-vaccination-guide-leaflet/information-on-hpv-vaccination

- 21. Kirwan PD, Hibbert M, Kall M, et al. HIV prevalence and HIV clinical outcomes of transgender and gender-diverse people in England. HIV Med 2021;22:131–9. 10.1111/hiv.12987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun XW, Kuhn L, Ellerbrock TV, et al. Human papillomavirus infection in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1343–9. 10.1056/NEJM199711063371903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human Papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus–positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:577–86. 10.1093/jnci/dji073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cameron JE, Hagensee ME. Human papillomavirus infection and disease in the HIV+ individual AIDS-associated viral. Aids-Associated Viral Oncogenesis 2007;185–213. 10.1007/978-0-387-46816-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaturvedi AK, Madeleine MM, Biggar RJ, et al. Risk of human papillomavirus–associated cancers among persons with AIDS. JNCI 2009;101:1120–30. 10.1093/jnci/djp205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palefsky JM. Anal squamous intraepithelial lesions: relation to HIV and human Papillomavirus infection. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 1999;21:S42–8. 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh V, Gratzer B, Gorbach PM, et al. Transgender women have higher human papillomavirus prevalence than men who have sex with men—two U.S. Sexual Trans Dis 2019;46:657–62. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Oliveira BR, Diniz E Silva BV, Dos Santos KC, et al. Human papillomavirus positivity at 3 anatomical sites among transgender women in central Brazil. Sex Transm Dis 2023;50:567–74. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Sluis WB, Buncamper ME, Bouman M-B, et al. Prevalence of neovaginal high-risk human papillomavirus among transgender women in the Netherlands. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:503–5. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uaamnuichai S, Panyakhamlerd K, Suwan A, et al. Neovaginal and anal high-risk human papillomavirus DNA among Thai transgender women in gender health clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2021;48:547–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. NHS population screening: information for trans and non-binary people, Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-population-screening-information-for-transgender-people/nhs-population-screening-information-for-trans-people [Accessed 8 Aug 2022].

- 32. Grosse A, Grosse C, Lenggenhager D, et al. Cytology of the neovagina in transgender women and individuals with congenital or acquired absence of a natural vagina. Cytopathology 2017;28:184–91. 10.1111/cyt.12417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fierz R, Ghisu GP, Fink D. Squamous carcinoma of the neovagina after male-to-female reconstruction surgery: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2019;2019:4820396. 10.1155/2019/4820396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2018;363:k4823. 10.1136/bmj.k4823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJF, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:172–83. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDowell M, Pardee DJ, Peitzmeier S, et al. Cervical cancer screening preferences among trans-masculine individuals: patient-collected human Papillomavirus vaginal Swabs versus provider-administered PAP tests. LGBT Health 2017;4:252–9. 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Welsh EF, Andrus EC, Sandler CB, et al. Cervicovaginal and anal self-sampling for HPV testing in a transgender and gender diverse population assigned female at birth: comfort, difficulty, and willingness to use. medRxiv 2023.:2023.08.15.23294132. 10.1101/2023.08.15.23294132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peitzmeier SM, Agénor M, Bernstein IM, et al. It can promote an existential crisis": factors influencing PAP test acceptability and utilization among transmasculine individuals. Qual Health Res 2017;27:2138–49. 10.1177/1049732317725513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Peitzmeier SM, et al. Comparing self- and provider-collected swabbing for HPV DNA testing in female-to-male transgender adult patients: a mixed-methods biobehavioral study protocol. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:444. 10.1186/s12879-017-2539-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Peitzmeier SM, et al. Test performance and acceptability of self- versus provider-collected swabs for high-risk HPV DNA testing in female-to-male trans masculine patients. PLoS One 2018;13:e0190172. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nyitray AG, Nitkowski J, McAuliffe TL, et al. Home-based self-sampling vs clinician sampling for anal precancer screening: the prevent anal cancer self-SWAB study. Int J Cancer 2023;153:843–53. 10.1002/ijc.34553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wolfrum SG, Koutsky LA, Hughes JP, et al. Evaluation of dry and wet transport of at-home self-collected vaginal swabs for human papillomavirus testing. J Med Microbiol 2012;61:1538–45. 10.1099/jmm.0.046110-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eperon I, Vassilakos P, Navarria I, et al. Randomized comparison of vaginal self-sampling by standard vs. dry swabs for human papillomavirus testing. BMC Cancer 2013;13:353. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nitkowski J, Giuliano A, Ridolfi T, et al. Effect of the environment on home-based self-sampling kits for anal cancer screening. J Virol Methods 2022;310:114616. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2022.114616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res 2009;44:2093–105. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Johnson A. National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles, Available: https://beta

- 48. Wagner S, Roberson D, Boland J, et al. Development of the Typeseq assay for detection of 51 human Papillomavirus Genotypes by next-generation sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 2019;57:e01794-18. 10.1128/JCM.01794-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weidlich S, Schellberg S, Scholten S, et al. Evaluation of self-collected versus health care professional (HCP)-Performed sampling and the potential impact on the diagnostic results of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections (Stis) in high-risk individuals. Infect Dis Rep 2023;15:470–7. 10.3390/idr15050047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2024-086099supp001.pdf (819.7KB, pdf)